Where Were You When Neil Armstrong Walked on the Moon?

On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin took “One giant leap for mankind" while the people of Planet Earth watched in awe.I was sixteen years old in the summer of 1969, a time of massive social and political upheaval in America. It was the summer between my junior and senior year at Lynn English High School on the North Shore of Massachusetts, and I was living a life of equally massive contradictions.Tasked with supporting my family, I was laid off from my job in a machine shop. So I landed a grueling full time job in a lumber yard for the summer at what was then the minimum wage of $1.60 per hour. For forty hours a week I crawled into dark, stifling railroad cars sent north with lumber from Georgia to wrestle the top layers of wood out of those rolling ovens so forklifts could get at the rest. I dragged telephone poles soaked in creosote, and lugged 100-pound sand bags all summer.While I was bulking up, the rest of my world was falling apart. On April 4th of the previous year, civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated by James Earl Ray in Memphis. Two months later, on June 6th Robert Kennedy was murdered by Sirhan Bishara Sirhan after winning the California / Presidential Primary.The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago erupted in unprecedented riots and violence. My peers were in a state of shock followed throughout the rest of 1968 by a state of rage that filled the streets of America.The nation was in chaos as the war in Vietnam escalated. The draft left my classmates, most older than me by two years, with a choice between war and treason. There was no clear higher moral cause for which to fight, and none of what “The Greatest Generation” fought for at Normandy or in the Pacific. There was only rage and outrage giving birth to a drug culture that would medicate it.Growing up in the shadows of Boston, the cradle of revolution and freedom, I was steeped in the liberal Democratic politics of our time. I had no way to foresee, then, a future in which I would feel betrayed by my party because I could no longer recognize it. Its embrace of a culture of death was still a few years away, but the seeds of that debasement of life were just beginning to tear away at our cultural soul.In his inaugural address in January of 1969, President Richard Nixon asked the nation to lower its voice and reach for unity instead of division. My peers had no appetite for unity. They knew nothing but their disillusionment. In the midst of it all, I rebelled in an opposite direction. I began to take seriously the Catholic heritage that I had previously ignored.But also in 1969, the Catholic Church, a once reliable source of hope and respite from the world, took a post-Vatican II kamikaze dive toward liturgical absurdity. “I never left the Church,” a TSW reader recently told me well into her reversion to faith. “The Church left me.” I felt a challenge to stay, however and it is a challenge I extend to all TSW readers. “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (John 6:68).It seems an odd thing, looking back on that summer, that as my Catholic peers dropped out of their faith, I chose that moment to drop in. I was reading Thomas Merton’s The Seven Story Mountain and The Sign of Jonas that summer, and they made sense to me. I began to pray, and before showing up to lug telephone poles each day at 8:00 AM, I began attending a 7:00 AM daily Mass where I looked very much out of place, but felt at home.

On July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin took “One giant leap for mankind" while the people of Planet Earth watched in awe.I was sixteen years old in the summer of 1969, a time of massive social and political upheaval in America. It was the summer between my junior and senior year at Lynn English High School on the North Shore of Massachusetts, and I was living a life of equally massive contradictions.Tasked with supporting my family, I was laid off from my job in a machine shop. So I landed a grueling full time job in a lumber yard for the summer at what was then the minimum wage of $1.60 per hour. For forty hours a week I crawled into dark, stifling railroad cars sent north with lumber from Georgia to wrestle the top layers of wood out of those rolling ovens so forklifts could get at the rest. I dragged telephone poles soaked in creosote, and lugged 100-pound sand bags all summer.While I was bulking up, the rest of my world was falling apart. On April 4th of the previous year, civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated by James Earl Ray in Memphis. Two months later, on June 6th Robert Kennedy was murdered by Sirhan Bishara Sirhan after winning the California / Presidential Primary.The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago erupted in unprecedented riots and violence. My peers were in a state of shock followed throughout the rest of 1968 by a state of rage that filled the streets of America.The nation was in chaos as the war in Vietnam escalated. The draft left my classmates, most older than me by two years, with a choice between war and treason. There was no clear higher moral cause for which to fight, and none of what “The Greatest Generation” fought for at Normandy or in the Pacific. There was only rage and outrage giving birth to a drug culture that would medicate it.Growing up in the shadows of Boston, the cradle of revolution and freedom, I was steeped in the liberal Democratic politics of our time. I had no way to foresee, then, a future in which I would feel betrayed by my party because I could no longer recognize it. Its embrace of a culture of death was still a few years away, but the seeds of that debasement of life were just beginning to tear away at our cultural soul.In his inaugural address in January of 1969, President Richard Nixon asked the nation to lower its voice and reach for unity instead of division. My peers had no appetite for unity. They knew nothing but their disillusionment. In the midst of it all, I rebelled in an opposite direction. I began to take seriously the Catholic heritage that I had previously ignored.But also in 1969, the Catholic Church, a once reliable source of hope and respite from the world, took a post-Vatican II kamikaze dive toward liturgical absurdity. “I never left the Church,” a TSW reader recently told me well into her reversion to faith. “The Church left me.” I felt a challenge to stay, however and it is a challenge I extend to all TSW readers. “Lord, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life” (John 6:68).It seems an odd thing, looking back on that summer, that as my Catholic peers dropped out of their faith, I chose that moment to drop in. I was reading Thomas Merton’s The Seven Story Mountain and The Sign of Jonas that summer, and they made sense to me. I began to pray, and before showing up to lug telephone poles each day at 8:00 AM, I began attending a 7:00 AM daily Mass where I looked very much out of place, but felt at home. “TRANQUILITY BASE HERE. THE EAGLE HAS LANDED”There were other things that marked that summer as horrible. On July 18, 1969, all of Boston watched in dismay as our last hope for a successor to the aura of John Fitzgerald Kennedy was rendered unfit for the presidency. On July 18, 1969, Senator Ted Kennedy drove his car off a narrow bridge on Chappaquiddick Island, and his only passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, was drowned as he saved himself. His presidential ambitions were thus ended.Then, just two days later, something amazing would eclipse that story and press the pause button on our 1969 world of chaos. It was an event that gave us all a time out from our Earthbound path of destruction. No one has written of it better than Kenneth Weaver. Writing for the December, 1969 edition of National Geographic, Mr. Weaver framed that awful year with a higher context in “One Giant Leap for Mankind.”Fifty years later, I remember well the story and its dialogue that Kenneth Weaver so masterfully wrote. I sat riveted and mesmerized through that dialogue with teeth clenched before a black and white TV screen late on the Sunday afternoon of July 20, 1969:

“TRANQUILITY BASE HERE. THE EAGLE HAS LANDED”There were other things that marked that summer as horrible. On July 18, 1969, all of Boston watched in dismay as our last hope for a successor to the aura of John Fitzgerald Kennedy was rendered unfit for the presidency. On July 18, 1969, Senator Ted Kennedy drove his car off a narrow bridge on Chappaquiddick Island, and his only passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, was drowned as he saved himself. His presidential ambitions were thus ended.Then, just two days later, something amazing would eclipse that story and press the pause button on our 1969 world of chaos. It was an event that gave us all a time out from our Earthbound path of destruction. No one has written of it better than Kenneth Weaver. Writing for the December, 1969 edition of National Geographic, Mr. Weaver framed that awful year with a higher context in “One Giant Leap for Mankind.”Fifty years later, I remember well the story and its dialogue that Kenneth Weaver so masterfully wrote. I sat riveted and mesmerized through that dialogue with teeth clenched before a black and white TV screen late on the Sunday afternoon of July 20, 1969:

“Two thousand feet above the Sea of Tranquility, the little silver, black, and gold space bug named Eagle braked itself with a tail of flame as it plunged toward the face of the moon. The two men inside strained to see their goal. Guided by numbers from their computer, they sighted through a grid on one triangular window.“Suddenly they spotted the onrushing target. What they saw set the adrenalin pumping and the blood racing. Instead of the level, obstacle-free plain called for in the Apollo 11 flight plan, they were aimed fora sharply etched crater, 600 feet across and surrounded by heavy boulders.“The problem was not completely unexpected. Shortly after Armstrong and his companion, Edwin (Buzz) Aldrin, had begun their powered dive for the lunar surface ten minutes earlier, they had checked against landmarks such as crater Naskelyne and discovered that they were going to land some distance beyond their intended target.“And there were other complications. Communications with Earth had been blacking out at intervals. The failures heightened an already palpable tension in the control room in Houston. This unprecedented landing was the trickiest, most dangerous part of the flight. Without information and help from the ground, Eagle might have to abandon its attempt.“The spacecraft’s all-important computer had repeatedly flashed the danger signals ‘1201’ and ‘1202’, warning of an overload. If continued, it would interfere with the computer’s job of calculating altitude and speed, and neither autopilot nor astronaut could guide Eagle to a safe landing.“Armstrong revealed nothing to the ground controllers about the crater ahead. Indeed, he said nothing at all, he was much too busy. The men back on Earth, a quarter of a million miles away, heard only the clipped, deadpan voice of Aldrin, reading off the instruments ‘Hang tight; we’re go. 2,000 feet.’“Telemetry on the ground showed the altitude dropping ... 1,600 feet ... 1,400 ... 1,000. The beleaguered computer flashed another warning. The two men far away said nothing. Not till Eagle reached 750 feet did Aldrin speak again. And now it was a terse litany: 750 [altitude], coming down at 23’[feet per second, or about 16 miles an hour]... At 330 feet Eagle was braking its fall, as it should, and nosing slowly forward.“But now the men in the control room in Houston realized that something was wrong. Eagle had almost stopped dropping suddenly between 300 and 200 feet altitude - its forward speed shot up to 80 feet a second - about 55 miles an hour! This was not according to plan.“At last forward speed slackened again and downward velocity picked up slightly... And then, abruptly, a red light flashed on Eagle’s instrument panel, and a warning came on in Mission Control. To the worried, flight controllers the meaning was clear, only 5 percent of Eagle’s descent fuel remained.“By mission rules, Eagle must be on the surface within 94 seconds or the crew must abort and give up the attempt to land on the moon. They would have to fire the descent engine full throttle and then ignite the ascent engine to get back into lunar orbit for a rendezvous with Columbia, the mother ship.“Sixty seconds to go. Every man in the control center held his breath. Failure would be especially hard to take now. Some four days and six hours before, the world had watched a perfect, spectacularly beautiful launch at Kennedy Space Center, Florida. Apollo 11 had flown flawlessly, uneventfully, almost to the moon. Now it could all be lost for lack of a few seconds of fuel.“‘Light’s on.’ Aldrin confirmed that the astronauts had seen the fuel warning light. ‘40 feet [altitude], picking up some dust. 30 feet. 20. Faint shadow.’“He had seen the shadow of one of the 68-inch probes extending from Eagle’s footpads. Thirty seconds to failure. In the control center, George Hage, Mission Director for Apollo 11, was pleading silently: “Get it down, Neil! Get it down!”“The seconds ticked away. ‘Forward, drifting right,’ Aldrin said. And then, with less than 20 seconds left, came the magic words: ‘O.K., engine stop.’ Then the now-famous words from Neil Armstrong: ‘Tranquility Base here. Eagle has landed!” (Kenneth Weaver, “One Giant Leap for Mankind,” National Geographic, December 1969)

ONE GIANT LEAP FOR MANKINDSix hours and thirty minutes later, I was still glued to a television at about 11:30 PM Eastern Daylight Time. The hatch of the Eagle Lunar Lander opened and Neil Armstrong, the Apollo 11 Mission Commander, backed slowly out before a captivated world. He paused on the ladder to lower an equipment storage assembly into position. Its 7-pound camera held earthlings spellbound.Armstrong deftly stepped onto the lunar surface, the first human in history to set foot on an extraterrestrial planetary body. He spoke into his microphone the famous words that would be forever etched into the annals of space exploration. His words were transmitted to a telescope dish at Canberra, Australia, then to a Comsat satellite above the Pacific, then to a switching station at Goddard Space Center near Washington, DC, and finally to Houston and the world:

ONE GIANT LEAP FOR MANKINDSix hours and thirty minutes later, I was still glued to a television at about 11:30 PM Eastern Daylight Time. The hatch of the Eagle Lunar Lander opened and Neil Armstrong, the Apollo 11 Mission Commander, backed slowly out before a captivated world. He paused on the ladder to lower an equipment storage assembly into position. Its 7-pound camera held earthlings spellbound.Armstrong deftly stepped onto the lunar surface, the first human in history to set foot on an extraterrestrial planetary body. He spoke into his microphone the famous words that would be forever etched into the annals of space exploration. His words were transmitted to a telescope dish at Canberra, Australia, then to a Comsat satellite above the Pacific, then to a switching station at Goddard Space Center near Washington, DC, and finally to Houston and the world:

“That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

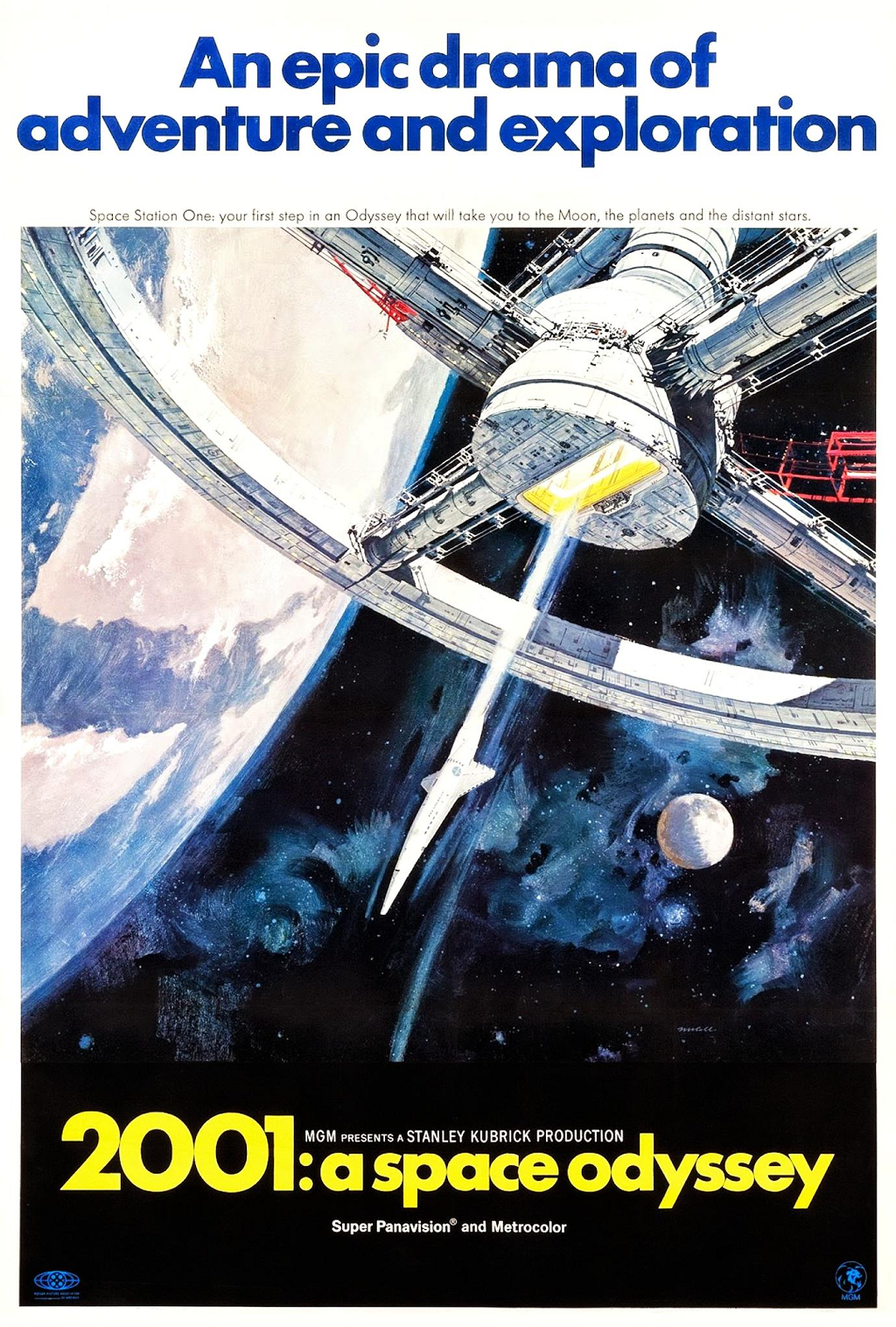

The months and years to follow revealed this lunar visit by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to be one of the most significant events of modern science. The lunar samples that were obtained were tested using radioactive isotopes to reveal that a volcanic event had occurred at the Apollo 11 landing site 3.7 billion years earlier. Other nearby samples revealed meteor remains from about 4.6 billion years ago, but nothing older than that.The conclusion drawn was that Earth’s Moon formed along with the rest of the Solar System about 4.6 billion years ago, one third the age of the Universe. After setting up dozens of other ongoing experiments, including a prismatic mirror for precise laser measurements from Earth, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin boarded Eagle for the eight-minute assent to the orbiting command module where astronaut Mike Collins waited. Sixty hours later, Apollo 11 and its crew were plucked from the Pacific.Science has not matched the vision humanity has had for its own ambitions. In the midst of all the chaos of 1969, the Stanley Kubrick film, 2001: A Space Odyssey earned the Academy Award for Special Visual Effects. The film envisioned manned flights to the moons of Jupiter by 2001, and an artificial intelligence named Hal 9000 who would not only control the mission, but plot nefariously against its human protagonists. You may recall the chilling line from Hal when astronaut David Bowman (Keir Dullea) wanted an electronic hatch open so he could return to the ship: “I’m sorry Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oR_e9y-bka0Writing a half century later in “Our Quest for Meaning in the Heavens” for The Wall Street Journal, Adam Kirsch hailed the first lunar landing of Apollo 11 as “what might be the greatest achievement in human history.” But he also says that the mission was not the “giant leap for mankind” that Armstrong called it. It was “more like humanity dipping a toe in the cosmic ocean, finding it too cold and lifeless to enter, and deciding to stay home.”No astronaut has ventured into space since the Space Shuttle program ended in 2011. Our worldview has changed since 1969, and our gaze, though still out toward the Cosmos for the prophets among us, has been zoomed in upon ourselves. An astronaut today might face censure for what Buzz Aldrin declared to all of humanity from space on the Apollo 11 mission’s way back to Earth:

“When I consider Thy heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the moon and the stars, which Thou has ordained; What is man that Thou should be mindful of him?” (Psalm 8:3)

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: My younger sister once told one of my friends that the only reason I became a priest was because Starfleet Academy denied my application. Please share this post about my other obsession, the bridges linking science and faith. You may like these related posts from These Stone Walls:

- The Final Frontier: Voyager-1 Enters Interstellar Space

- E.T. and The Fermi Paradox: Are We Alone in the Cosmos?

- The March for Life and the People on the Planet Next Door

- Misguiding Light: Young Catholics Leaving Faith for Science