Pope Francis and the Lost Sheep of a Lonely Revolution

Pope Francis once again stirs anxiety with the Apostolic Exhortation, “Amoris laetitia,” raising anew a long pondered critique: Is the Pope Catholic?I’ll never forget that urgent knock on my seminary room door as I looked up from my typewriter. It was October, 1978, my first year of theology at Saint Mary Seminary & University in the Roland Park area of Baltimore. An unknown voice through the door said that the pope had died. “I know!” I replied. “That was over a month ago.” “No,” said the persistent voice, the NEW pope has died!” When I arrived at “Roland Park,” as that seminary was called, my friend Leo Demers sent me a small black & white TV with extendable rabbit ears. Remember those? I quickly turned it on and saw the shadowy footage from Rome announcing the sudden death of Pope John Paul I after 33 days in the Chair of Peter. In an instant, the world changed.I spontaneously thought of that day when, just three years ago, a very similar knock came, this time on my penitentiary cell door, and again I looked up from my typewriter. “Can the pope quit?” asked a young man standing at my door. “No,” I said thinking that he was merely passing time in a game of Trivial Pursuit. “It hasn’t happened in hundreds of years.” “Well I think this one just did,” said the prisoner. I quickly turned on my small TV, and my spirits fell crashing to the floor. Pope Benedict was abdicating the papacy. It felt devastating!I wrote of that dismal time while still in the midst of it in “Pope Benedict XVI: The Sacrifices of a Father’s Love.” It appeared just a day before his departure from the Vatican on February 28, 2013. Like the rest of the world that night, I watched with a heavy heart as the helicopter bearing Benedict the Beloved circled the dome of St. Peter’s twice, crossed Rome, then hovered for a moment above the Roman Colosseum, a scene captured in my post “On the Successor of Peter Amid the Wind and the Waves.” And again, the whole world changed.Did it change for the better, or was it a further descent down the chasm of moral relativism into which Western Civilization plunged in the final decades of the 20th Century? Only time and history can answer that, and the ballots are not all in. For the moment, many in the Catholic world have been plunged into the latest in a string of controversies, this time over whether and how much Pope Francis, three years into his papacy, is redirecting the Catholic Church in the modern world. That he is a good man, no one doubts. That he is a reformer is crystal clear. What the limits are on his reform we do not yet know, but his leadership style and off-the-cuff manner of addressing the world is foreign to those more comfortable with the carefully prepared texts of his predecessors.

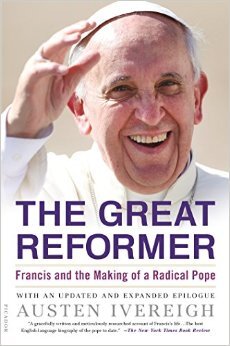

Pope Francis once again stirs anxiety with the Apostolic Exhortation, “Amoris laetitia,” raising anew a long pondered critique: Is the Pope Catholic?I’ll never forget that urgent knock on my seminary room door as I looked up from my typewriter. It was October, 1978, my first year of theology at Saint Mary Seminary & University in the Roland Park area of Baltimore. An unknown voice through the door said that the pope had died. “I know!” I replied. “That was over a month ago.” “No,” said the persistent voice, the NEW pope has died!” When I arrived at “Roland Park,” as that seminary was called, my friend Leo Demers sent me a small black & white TV with extendable rabbit ears. Remember those? I quickly turned it on and saw the shadowy footage from Rome announcing the sudden death of Pope John Paul I after 33 days in the Chair of Peter. In an instant, the world changed.I spontaneously thought of that day when, just three years ago, a very similar knock came, this time on my penitentiary cell door, and again I looked up from my typewriter. “Can the pope quit?” asked a young man standing at my door. “No,” I said thinking that he was merely passing time in a game of Trivial Pursuit. “It hasn’t happened in hundreds of years.” “Well I think this one just did,” said the prisoner. I quickly turned on my small TV, and my spirits fell crashing to the floor. Pope Benedict was abdicating the papacy. It felt devastating!I wrote of that dismal time while still in the midst of it in “Pope Benedict XVI: The Sacrifices of a Father’s Love.” It appeared just a day before his departure from the Vatican on February 28, 2013. Like the rest of the world that night, I watched with a heavy heart as the helicopter bearing Benedict the Beloved circled the dome of St. Peter’s twice, crossed Rome, then hovered for a moment above the Roman Colosseum, a scene captured in my post “On the Successor of Peter Amid the Wind and the Waves.” And again, the whole world changed.Did it change for the better, or was it a further descent down the chasm of moral relativism into which Western Civilization plunged in the final decades of the 20th Century? Only time and history can answer that, and the ballots are not all in. For the moment, many in the Catholic world have been plunged into the latest in a string of controversies, this time over whether and how much Pope Francis, three years into his papacy, is redirecting the Catholic Church in the modern world. That he is a good man, no one doubts. That he is a reformer is crystal clear. What the limits are on his reform we do not yet know, but his leadership style and off-the-cuff manner of addressing the world is foreign to those more comfortable with the carefully prepared texts of his predecessors. For some, Pope Francis can be downright alarming. In the weeks leading up to publication of the latest Vatican controversy, the Apostolic Exhortation, “Amoris laetitia” (On Love in the Family), I received something far more instructive that goes to the heart, not only of Pope Francis, but of the state of the Church. It’s a brilliant biography by British Journalist Austen Ivereigh entitled, The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope (Henry Holt 2014).At the outset, its very subtitle is disconcerting. “The Making of a Radical Pope” doesn’t exactly sound like a source for bridge building between the polar ideologies that have become central for many Catholics. But there are some things to be learned from this book, some very important things, including what the book describes as “the hitherto untold story of how and why he was elected pope.”Before I begin the framework of that fascinating story, I have to admit that I have not yet fully read “Amoris laetitia,” the source of all the latest anxiety in the Catholic on-line world some of which, unlike the rest, of Western journalism, tends to lean right. I understand the anxiety - I have it, too - but it may take time for me to obtain and review the full document. For now, I’ve read only excerpts of the document, but I have read a lot about it, and in sources I trust and recommend.Cardinal Raymond Burke set the minds of some at ease with a brief, incisive analyis entitled “‘Amoris laetitia’ and the Constant Teaching and Practice of the Church” (NCRegister.com, April 11, 2016). Missionary of Mercy Father George David Byers has also been posting some astute reflections at Arise! Let us be going! And for a more secular view, Detroit News Editor Nicholas G. Hahn had an excellent analysis in The Wall Street Journal (“Missing the Bigger Story About the Pope,” April 15).It is that “bigger story” that I wish to address as I await a copy of the full text of “Amoris laetitia.” The best tool I have come across for understanding the man behind it is The Great Reformer, the riveting biography of Pope Francis by Austen Ivereigh, and especially his description of the state of the Church and Roman Curia as Benedict XVI stepped down. Those sections alone make this book a must read in my opinion.“IN THOSE WEIRD, INTERIM DAYS”!The Conclave of 2013 was unique. First of all, there was no funeral to attend, no sacramental goodbye that captured the world’s attention. The simultaneous drama of the resignation of a pope whose entire life was immersed in the affairs of Europe, and the emergence of the first pope from the New World, had no precedent in Church history. The expectations and hopes of the entire Vatican culture were under a global microscope.Jorge Mario Cardinal Bergoglio, age 76, had no expectation that he might be staying in Rome after the conclave. He had a return ticket, and had asked his Argentine newspaper carrier to keep delivering La Nación until his return. He was “off the papabile radar - partly because of his age,” and partly because he had spent little time in Rome and “was invisible” when he visited, according to Austen Ivereigh. He was also a runner-up in 2005, and “no runner-up at a conclave had ever been elected pope in a following one.” On the day he arrived for the conclave...

For some, Pope Francis can be downright alarming. In the weeks leading up to publication of the latest Vatican controversy, the Apostolic Exhortation, “Amoris laetitia” (On Love in the Family), I received something far more instructive that goes to the heart, not only of Pope Francis, but of the state of the Church. It’s a brilliant biography by British Journalist Austen Ivereigh entitled, The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope (Henry Holt 2014).At the outset, its very subtitle is disconcerting. “The Making of a Radical Pope” doesn’t exactly sound like a source for bridge building between the polar ideologies that have become central for many Catholics. But there are some things to be learned from this book, some very important things, including what the book describes as “the hitherto untold story of how and why he was elected pope.”Before I begin the framework of that fascinating story, I have to admit that I have not yet fully read “Amoris laetitia,” the source of all the latest anxiety in the Catholic on-line world some of which, unlike the rest, of Western journalism, tends to lean right. I understand the anxiety - I have it, too - but it may take time for me to obtain and review the full document. For now, I’ve read only excerpts of the document, but I have read a lot about it, and in sources I trust and recommend.Cardinal Raymond Burke set the minds of some at ease with a brief, incisive analyis entitled “‘Amoris laetitia’ and the Constant Teaching and Practice of the Church” (NCRegister.com, April 11, 2016). Missionary of Mercy Father George David Byers has also been posting some astute reflections at Arise! Let us be going! And for a more secular view, Detroit News Editor Nicholas G. Hahn had an excellent analysis in The Wall Street Journal (“Missing the Bigger Story About the Pope,” April 15).It is that “bigger story” that I wish to address as I await a copy of the full text of “Amoris laetitia.” The best tool I have come across for understanding the man behind it is The Great Reformer, the riveting biography of Pope Francis by Austen Ivereigh, and especially his description of the state of the Church and Roman Curia as Benedict XVI stepped down. Those sections alone make this book a must read in my opinion.“IN THOSE WEIRD, INTERIM DAYS”!The Conclave of 2013 was unique. First of all, there was no funeral to attend, no sacramental goodbye that captured the world’s attention. The simultaneous drama of the resignation of a pope whose entire life was immersed in the affairs of Europe, and the emergence of the first pope from the New World, had no precedent in Church history. The expectations and hopes of the entire Vatican culture were under a global microscope.Jorge Mario Cardinal Bergoglio, age 76, had no expectation that he might be staying in Rome after the conclave. He had a return ticket, and had asked his Argentine newspaper carrier to keep delivering La Nación until his return. He was “off the papabile radar - partly because of his age,” and partly because he had spent little time in Rome and “was invisible” when he visited, according to Austen Ivereigh. He was also a runner-up in 2005, and “no runner-up at a conclave had ever been elected pope in a following one.” On the day he arrived for the conclave...

“ ... on the other side of the Tiber, Benedict XVI was giving his last general audience, telling tens of thousands in St. Peter’s Square of the peace of mind his decision had brought him, how there had been times in his eight-year papacy when the water was rough and ‘the Lord seemed to sleep.’” (The Great Reformer, p. 351)

There were 151 cardinals in Rome for the conclave, 115 of them under the age of eighty and eligible to vote. It was the same number that elected Benedict in 2005. However, the cardinals knew each other better than in 2005 because Benedict had brought them together five times in his eight-year papacy.Two of the best known, Cardinal Angelo Sodano, the dean, and Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, Chamberlain, were too associated with Vatican scandals to be serious considerations at the conclave. As Austen Ivereigh explains, “it was broadly known that Vatican corruption and dysfunction were a common thread in the speeches” of the general congregations held behind closed doors, and...

“three cardinals appointed months before by Pope Benedict to probe the rot were on hand to brief their confreres on their three-hundred-page confidential report which would be on the next pope’s desk” (p. 352).

The central governance of the Church was in crisis. Cardinal Carlo Maria Vigano, Apostolic Nuncio to the United States, had previously warned Pope Benedict that the Secretary of State named him to that post in October, 2011 “to get him out of Rome after he had uncovered corruption in the awarding of contracts that cost the Holy See millions of Euros.” Deeply shocked, the arriving cardinals, especially from the United States and Germany, were determined that the next pope “would bring a big broom,” and, as Cardinal Timothy Dolan later wrote of the conclave, “We knew that the world awaited the election of a pontiff who might usher in some significant reforms that begged for implementation within the Church.”In other words, the pope was elected with the conclave’s clear intent that he would be a reformer, for the status quo among the curia entailed more than simple dysfunction and financial corruption. “It was also about petty factionalism,” wrote Mr. Ivereigh, which “led to some being promoted beyond their abilities and others with the right qualifications being frozen out.” The so-called “gay lobby... used blackmail and preferment to protect and advance its interests.” A consensus had built around the determination that “what was needed was wholesale culture change - a new ethos of service to the pope’s mission.’In a pre-conclave interview with Father Thomas Rosica, Boston Cardinal Sean O’Malley said, “We were all pretty certain that there would be dramatic changes, and a new way of looking at the curia, with more collegiality.” The previous year, in 2012, Cardinal Bergoglio was among those who traveled to Rome for the February consistory and the creation of twenty-two new cardinals. “The headlines were full of the Vatileaks scandal,” Austen Ivereigh described, and it “would reach new depths in May [2012] with the publication of documents copied from the pope’s desk.” The documents were stolen and released by Pope Benedict’s butler, Paolo Gabriel who himself “acted out of frustration...to sound the alarm, to show the world what was happening and to force action” (p. 343).While visiting Mexico in 2012, Pope Benedict fell, striking his head, a fact that few knew about. “As painful as the Vatileaks scandal was for him, it was this [fall] that led Benedict XVI to design a plan to stand down,” the first pope in 600 years to do so. I wrote of what I correctly understood to be his motives for stepping down in “Pope Benedict XVI: The Sacrifices of a Father’s Love.” POPE FRANCIS IN THE CRUCIBLE OF SCANDALAt the conclave a year later, amid talk of the need for reform of the curia and the status quo in Rome, 76-year--old Cardinal Bergoglio delivered a speech about “the Church’s reason for being,” about the “existential peripheries”:

POPE FRANCIS IN THE CRUCIBLE OF SCANDALAt the conclave a year later, amid talk of the need for reform of the curia and the status quo in Rome, 76-year--old Cardinal Bergoglio delivered a speech about “the Church’s reason for being,” about the “existential peripheries”:

“those of the mystery of sin, of suffering, of injustice, of ignorance ... The evils that, over time, appear in Church institutions have their root in self-referentiality, a kind of theological narcissism... The self-referential Church presumes to keep Jesus Christ for itself and not let him out.”

From my own perspective, the first signs of reform not only of governance, but of justice and its necessary other side - mercy - came in 2014 when representatives of the Holy See were hauled before a United Nations commission to be grilled about a sexual abuse scandal in the priesthood. It was a brazen, media-driven example of the U.N. examining the splinter in the Church’s eye while ignoring the plank in its own. I wrote about this twice in “The U.N. in the Time of Cholera,” and “The United Nations High Commissioner of Hypocrisy.” Even Austen Ivereigh, whose research seems otherwise impeccable, quoted a source (the Associated Press) that presented this part of the story incompletely:

“The Vatican also amended its own regulations to make the process of laicization - stripping a man of his priesthood, a power reserved to the Vatican - faster and easier. Of the 3,400 cases reported by local dioceses to the Holy See between 2004 and 2011, 848 priests were laicized while 2,572 were punished with lesser penalties - usually old men who had spent time in prison for their crimes.” (p. 126)

Though the 3,400 cases were reported to Rome between 2004 and 2011, most were claims alleged to have taken place decades earlier, but surfacing for the first time only when it became clear that dioceses, especially in the United States, would settle these cases for big bucks and with few questions asked. Few of these “old men” spent time in prison because statutes of limitation for just prosecutions had expired. Were some of the 848 laicized priests guilty? Clearly so. Were some of them innocent? Likely so, but we will never know because little if any effort took place locally to assure due process before claims were labeled “credible.” As difficult as it is to believe, local dioceses did little to distinguish between true crimes and mere accusations.Pope Francis proved, not so eager to see the priesthood and Church become convenient scapegoats for this U.N. committee. He pointed out that the Catholic Church “was perhaps the single public institution to have moved with transparency and responsibility,” and added, “No one has done more, yet the Church is the only one to have been attacked.” He also praised Benedict XVI for his “very courageous” efforts at reform. Austen Ivereigh described the fallout of this Pope’s refusal to stick with the victim culture’s imposed narrative:

“Among many furious reactions was that of the Survivors’ Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), which had been delighted by the U.N. report [but] now said that Francis had ‘an archaic, defensive mindset...’” (p. 128)

That was perhaps the clearest indication that in the matter of Church governance and the application of justice, reform is indeed underway, and it’s a fact for which I am grateful.But gratitude does not mitigate all concerns. The “existential peripheries” of which Pope Francis writes bring me to his favorite and most oft-cited Gospel passage, the Parable of the Prodigal Son, what Austen Ivereigh calls “an iconic Gospel tale of God’s reckless mercy.” I cannot omit from it a just reflection by Anthony Esolen in Crisis Magazine entitled, “Who Will Rescue the Lost Sheep of the Lonely Revolution?”

“That is why you came among us, to call sinners back to the fold. Not to pet and stroke them for being sinners, because that is what you meant by ‘lost,’ and what you meant by ‘dead’ when you ask us to consider the young man who had wandered into the far country. The father in your parable wanted his son alive, not dead.”

And he wanted very much for that older brother to come back inside, “for you are always with me, and all that I have is yours” (Luke 15:31).[video align="center" aspect_ratio="16:9" width="90" autoplay=“0”]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zmXiFMHzpgo[/video]Editor's Note: Father Dwight Longenecker wrote an excellent analysis on the objective distinctions between being a Catholic traditionalist and being a Catholic fundamentalist.