“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

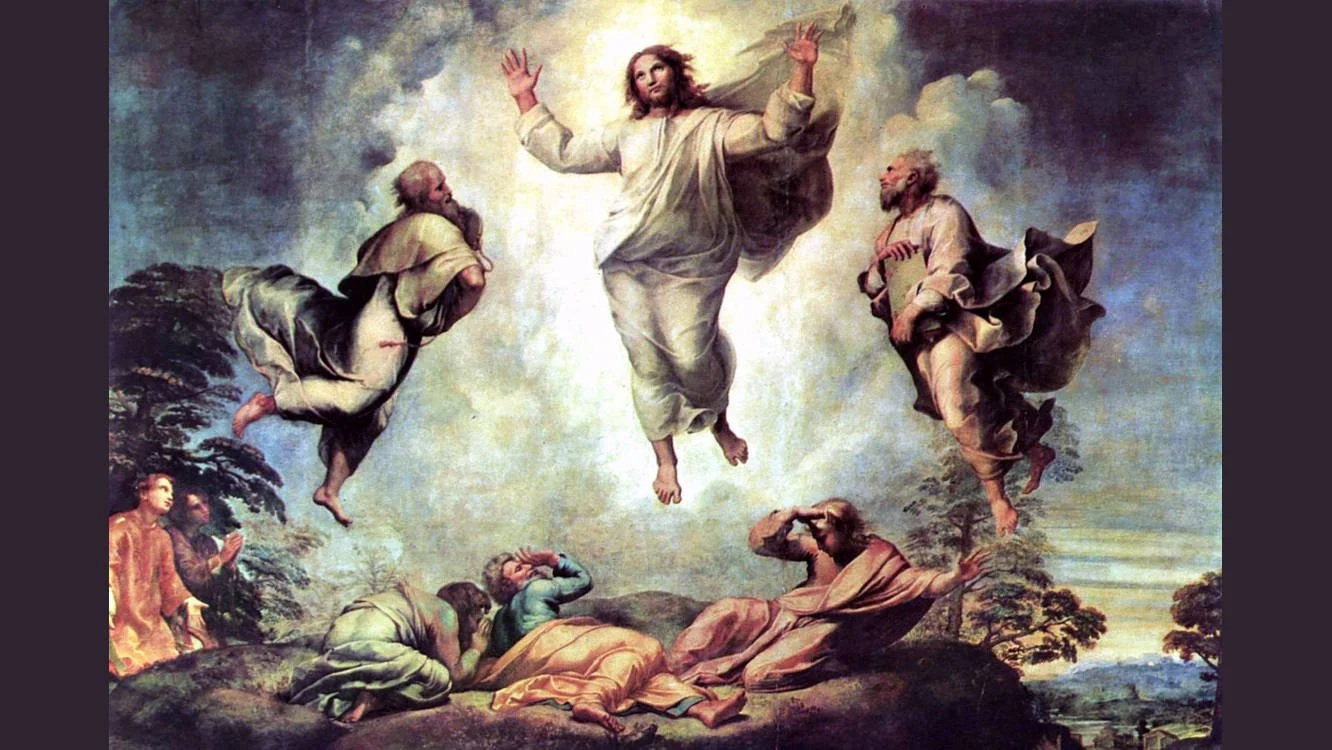

The Law and the Prophets and the Transfiguration of Christ

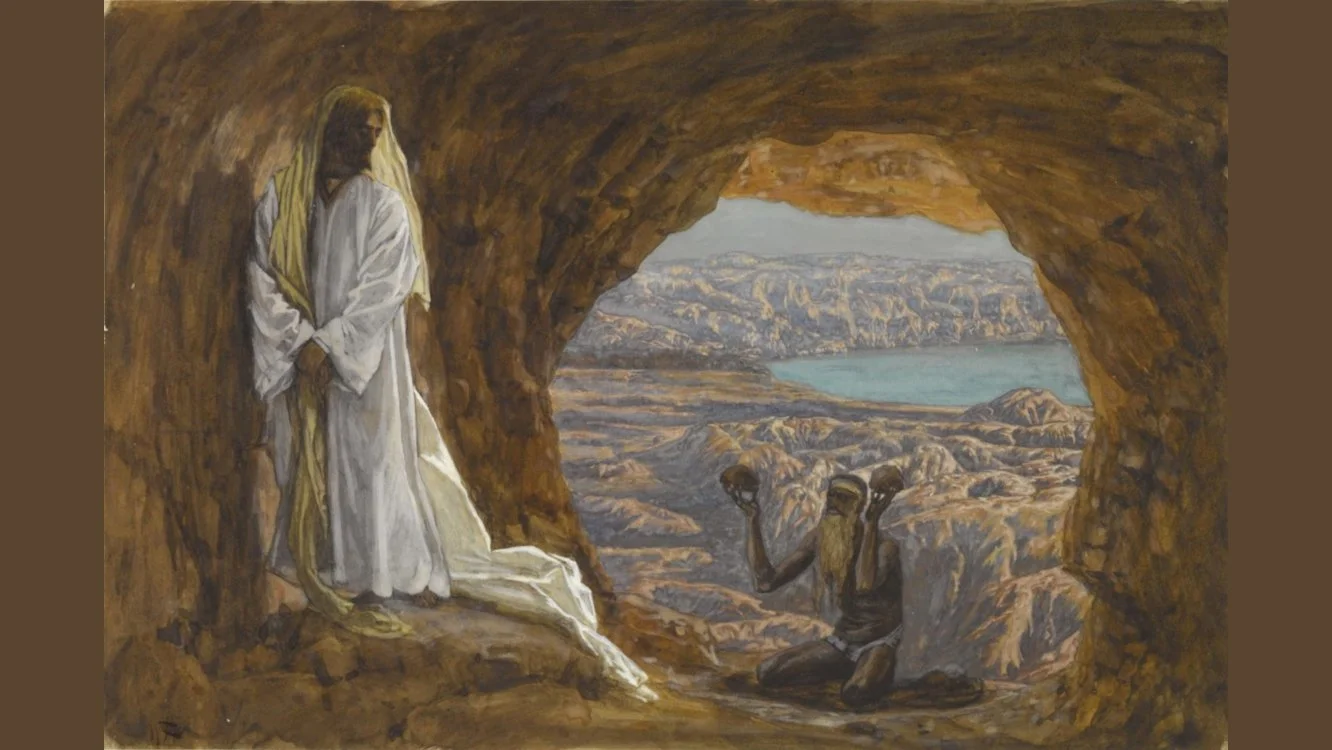

Moses and the Prophet Elijah are present for the Transfiguration of Christ. They represent the Law and the Prophets, the two pillars of Israel's faith and ours.

Moses and the Prophet Elijah are present for the Transfiguration of Christ. They represent the Law and the Prophets, the two pillars of Israel's faith and ours.

February 25, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

“Nothing new in the Holy See.” I hear these words from our Editor every week as she reviews with me a global traffic report for this blog. Being blind behind these stone walls to everything going on with a post after it leaves my archaic typewriter, this opportunity to know that someone out there is actually reading is vaguely comforting to me. We cannot know who is reading any particular post, but we can see where they are, and how many they are.

Our call always ends with “Nothing new in the Holy See.” It means that no one there has stopped to look from Beyond These Stone Walls. There is a sadness in that. There is a lot of controversy in Rome these days, and because I have a stake in it, I am both anxious about it and anxious to have a voice in it. I look intently at the affairs of Rome even if no one there is ever looking back. Current events there are sometimes manipulated by those with an agenda to reshape the Church in their own image, or to filter the Way, the Truth, and the Light through the age of relativism.

But all this has more to do with our politics than the far more important opportunities to explore, and allow to be shaped within us, the profoundness of our faith. Unlike other Catholic bloggers, I can write only one post per week so the affairs of Rome will have to wait. It is Lent, after all, and the Transfiguration of Christ in the Gospel this week shakes the Earth under my feet while the affairs of Rome only make me tremble a bit.

So no offense to my fellow Catholics embroiled over the dramas of Rome, and the tug-of-war closer to home as struggles over altar rails and Latin in the Mass threaten to replace our struggle to live the Gospel. I am painfully aware that in 2013 Pope Benedict XVI left the Chair of Peter. My entire life as a priest had been overshadowed by the light of two great men who became giants not only in faith but in the world. I will never forget that 1978 knock on my seminary room door and the voice that followed: “The Pope has died!” I shouted back, “That happened a month ago!” The face of the Church in the modern world changed as the first non-Italian in centuries became pontiff in the person of Saint John Paul II. Twenty-six years later in 2005 he was followed in the papacy by the brilliant Joseph Ratzinger, a theologian par excellence who became Benedict XVI. I have always been aware that the two popes who followed them had to fill the shoes of giants, so I have to always remind myself to cut them a little slack. I fend off any tendency to judge or compare them with their predecessors.

These are dark days for priests, and often dark for faithful Catholics as well. But darkness preceded the Transfiguration of Christ at the center of the Gospel for the Second Sunday of Lent, and as usual there is a story on its surface and a far greater one in its depths. Lord, be our Light.

Who Do You Say That I Am?

All three Synoptic Gospels have an account of the Transfiguration of Jesus, and the accounts are remarkably uniform. This week for the Second Sunday of Lent, it is Matthew’s turn, but all the elements he presents in his presentation of the Transfiguration of Christ are also presented by Luke who adds a component. Luke alone presents a reason for the Lord to bring three of His Apostles to the top of Mount Tabor:

“Jesus took Peter, James and John and went up the mountain to pray. While he was praying his face changed in appearance and his clothing became dazzling white. And behold, two men were conversing with him, Moses and Elijah, who appeared in glory and spoke of his exodus that he was going to accomplish in Jerusalem.”

— Luke 9:28-30

I wrote of this same event and its place in Salvation History in my recent post, “Covenants of God.”

Some immediate understanding of this event would have dawned upon any faithful Jew and certainly registered with Peter, James and John. The account is highly reminiscent of an event in the Book of Exodus that took place some 13 centuries earlier:

“When Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tablets of the Law in his hands, as he came down from the mountain Moses did not know that the skin of his face shone because he had been talking with God. And when Aaron and all the people of Israel saw Moses, because the skin of his face shown, they were afraid to come near him.”

— Exodus 34:29-30

Though the event of the Transfiguration of Jesus would vividly bring to the Jewish mind that passage from Exodus, it was also very different. It was like the difference between the Sun and the Moon. The Moon only reflects light radiated from the Sun. As brilliant as a full moon can appear in the darkness of night, it produces no light of its own. The face of Moses only reflected the light of grace radiated from God.

The Sun, on the other hand, radiates its own dazzling light, and to look too long would cause blindness. The light of the Transfiguration of Christ was “dazzling,” and it came from within. In those few moments — for Peter, James and John could have stood no more than a few — God lifted a corner of the veil to reveal the nature of the person Peter declared to be the Christ:

“The only begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father, through him all things were made. For our salvation he came down from heaven.”

— The Nicene Creed

I wrote of this account a few years ago in “A Transfiguration Before Our Very Eyes.” That post was more about the conversion that this episode can bring within a person who comes to some understanding of its spiritual dimensions. Canadian Catholic blogger Michael Brandon at “Free Through Truth” actually wrote a post about that post — and his was far better than mine — which he entitled, “Transfiguration, You and Me.”

The conversion that Michael Brandon and I both highlighted was that of Pornchai Moontri, and it is a most important story, not just for him, or for me, but for a Church embroiled in scandal. If you think I may beat this drum of Pornchai’s conversion too much, I challenge you to delve into it for I cannot emphasize it enough. Given the story told in “Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom,” his conversion — a change not just of heart but of substance — should have been impossible. And he found no light in me, for I radiate none.

In the Gospel, the Transfiguration of Jesus was preceded by two pivotal events. On the command of Jesus, the Apostles fed 5,000 people with a mere five loaves of bread and two fish. When it was over, he asked the Apostles, “Who do the people say that I am?” They answered, “Some say John the Baptist” (for he had already been beheaded by Herod) “while some say Elijah or that one of the prophets of old has arisen.”

But what about you, asked Jesus. “Who do you say that I am?” Peter answered for all: “You are the Christ of God”. Jesus then told them a startling revelation bringing them to an inner darkness:

“You are to tell this to no one. The Son of Man, must suffer many things, be rejected by the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised. If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it; and whoever will lose his life for my sake, will save it.”

So answer for yourself the question that Jesus asked Peter, and, through the Gospel, asks each of us: “Who do you say that I am?” But before you answer, keep in mind a central tenet of human nature. Just like many of the Jews in the desert with Moses after having been delivered from bondage in Egypt, how many Catholics do you know who do not esteem the faith they inherited through the Blood of the Lamb of God and was passed on to us through countless martyrs at the cost of their lives? Your answer must cost you something of yourself. “What you inherit too cheap you may esteem too lightly.”

A Conversation with Moses and Elijah

I would like to delve deeper into the theological significance of the Transfiguration account and into its spiritual resonance. First, the very important story behind the story. The account is filled with great spiritual meaning. First, why do Moses and Elijah appear?

A lot in Sacred Scripture happens on mountaintops. In the Book of Exodus, Moses received the Covenant from God on Mount Sinai. In the First Book of Kings, the Prophet Elijah encountered God on Mount Horeb. On Mount Tabor — the place where long-held tradition places the Transfiguration — Moses and Elijah represent the Law and the Prophets, the two central pillars of faith in Judaism, and the foundations of God’s Covenant with Israel.

But how can they be present in heaven before the Resurrection of Jesus and the Exodus from sin and death? The greatness of Elijah is attested to by the sheer number of allusions to him in both the Old and New Testaments. In the Hebrew mind, it was Elijah who affirmed the supremacy of Yahweh over nature and human history, and was seen as the principal defender of traditional Hebrew morality.

Elijah can be present at the Transfiguration because he was taken on a chariot into heaven (2 Kings 2:1-18). It was an ingrained belief of Hebrew tradition that God would return Elijah to Israel even before this prophecy was set forth by the Prophet Malachi: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and terrible Day of the Lord comes” (Malachi 4:5). Knowing the Scriptures, the presence of Elijah must have struck both hope and terror into the hearts of Peter, James and John.

But how is it that Moses was there with Jesus on Mount Tabor? This is where the Hebrew Scriptures and the legends of faith intersect. The Canon of Sacred Scripture reveals the story of Salvation History from Abraham to Jesus, but Israel also had a collection of oral and written traditions accepted by Rabbinical teaching as “Deuterocanonical” meaning, “Secondary Canon.” Some of these are also called “Apocryphal” texts from the Greek, “apokryphos” which means “hidden.” Some of what is in these texts intersects with the Bible, but remains a matter of pious traditional belief instead of historical verification. I once wrote of these discoveries in “Qumran: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Coming Apocalypse.” There are others perhaps not yet discovered. The Book of Daniel (12:9) speaks of “words that are shut up until the end of time.”

An example of how one such text contributed to popular belief is the “Protoevangelium of James.” It circulated in the Early Church and was cited by one of the Church Fathers. It is the only source for a tradition that the parents of Mary were Joachim and Anna.

There were several texts outside of Scripture from which legends and traditions circulated regarding Moses. These include the Books of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees, and the Assumption of Moses. They influenced early Rabbinic beliefs and teachings about angels, for example, and the lives of Moses and other Biblical figures.

The Assumption of Moses reveals a tradition, now lost from the fragments of the text that have survived, about the death of Moses in the Sinai desert. In that legend, Satan tried to claim the body of Moses, but Michael the Archangel contended with Satan and won. Michael then escorted Moses into heaven, like Elijah, body and soul. That this legend became engraved into the beliefs of Israel, and passed to the Early Christian Church, is evident in the New Testament Letter of Jude who is writing to an audience that obviously already knows of the account:

“But when the Archangel Michael, contending with the devil, disputed about the body of Moses, he did not presume to pronounce a reviling judgment upon him, but said, ‘The Lord Rebuke you.’ ”

— Jude 1:9

It may be from this legendary story that, from the earliest time in the Christian Church, Saint Michael the Archangel has the role of escorting the souls of the dead to salvation. This is how Moses could thus be present with Elijah at the Transfiguration where they are reported to have discussed with Jesus the Cross, the Second Exodus. The road upon which Jesus is embarked is connected to the Law and the Prophets. It is to be an Exodus from the bondage of sin and death in which God will Himself pay the price for release that he once exacted from Pharaoh: The sacrificial death of his own Son.

The Feast of Tabernacles

The entire Gospel account of Transfiguration takes place against the backdrop of the Feast of Tabernacles. This is why, in his dreamlike ecstatic state, Peter wants to delay the parting of Moses and Elijah from Jesus by saying,

“Master, it is good that we are here. Let us make three tents, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.”

Peter misinterprets the reason why they are all present in that place as being the annual Harvest Feast of Tabernacles (or tents), called in Hebrew, “Sukkot.” It is one of three Pilgrimage Feasts in the Hebrew calendar. It was originally a harvest feast, something like the American Thanksgiving, and called the “Feast of Ingathering” in the earliest Hebrew traditions. It lasts for seven days.

As I researched the connection between the Feast of Tabernacles, with its origin in Exodus 23:16, and the Transfiguration of Christ some thirteen centuries later, I came upon a long and detailed article about its history. As I studied the article, I was shocked to see at the end that it was written by my uncle, the late Father George W. MacRae, a renowned Scripture scholar who became rector of the École biblique et archéologique française de Jérusalem and Stillman Professor of Catholic Studies at Harvard University. It was an article he wrote for Catholic Biblical Quarterly in 1960, much of which became included in the New Jerome Biblical Commentary.

The Feast of Sukkot — variously interpreted as Tabernacles, Tents, Huts or Booths — had its roots in early Palestine as little huts were built in the fields, orchards and vineyards during the harvest. Much later, the Pilgrimage Feast was given a deeper religious meaning when it became connected to the events of the Exodus as a memorial to how the Israelites lived during their forty years of wandering in the desert after following Moses through the Red Sea.

It is an irony of Biblical proportions that this formed the scene for the revelation of Jesus as the Son of God about to enter Jerusalem for the New Exodus, the Exodus through the Red Sea of sin and death. It is the Exodus of the Cross through which Jesus will lead us to the New Jerusalem, the Promised Land, if we pick up our Cross and follow Him.

“This is my Son, my Chosen. Listen to him.”

— Luke 9:35

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Qumran: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Coming Apocalypse

He Has His Mother’s Eyes: The Vision of Our Lady of Guadalupe

“What Shall I Do to Inherit Eternal Life?” (Luke 10:25)

On Good Authority, “Salvation Is from the Jews”

Readers have told us that our Sacred Scripture collection, The Bible Speaks, is a treasure trove of meaningful biblical literature and fine reading for Lent.

Don’t be a stranger. Follow Father Gordon MacRae on X.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

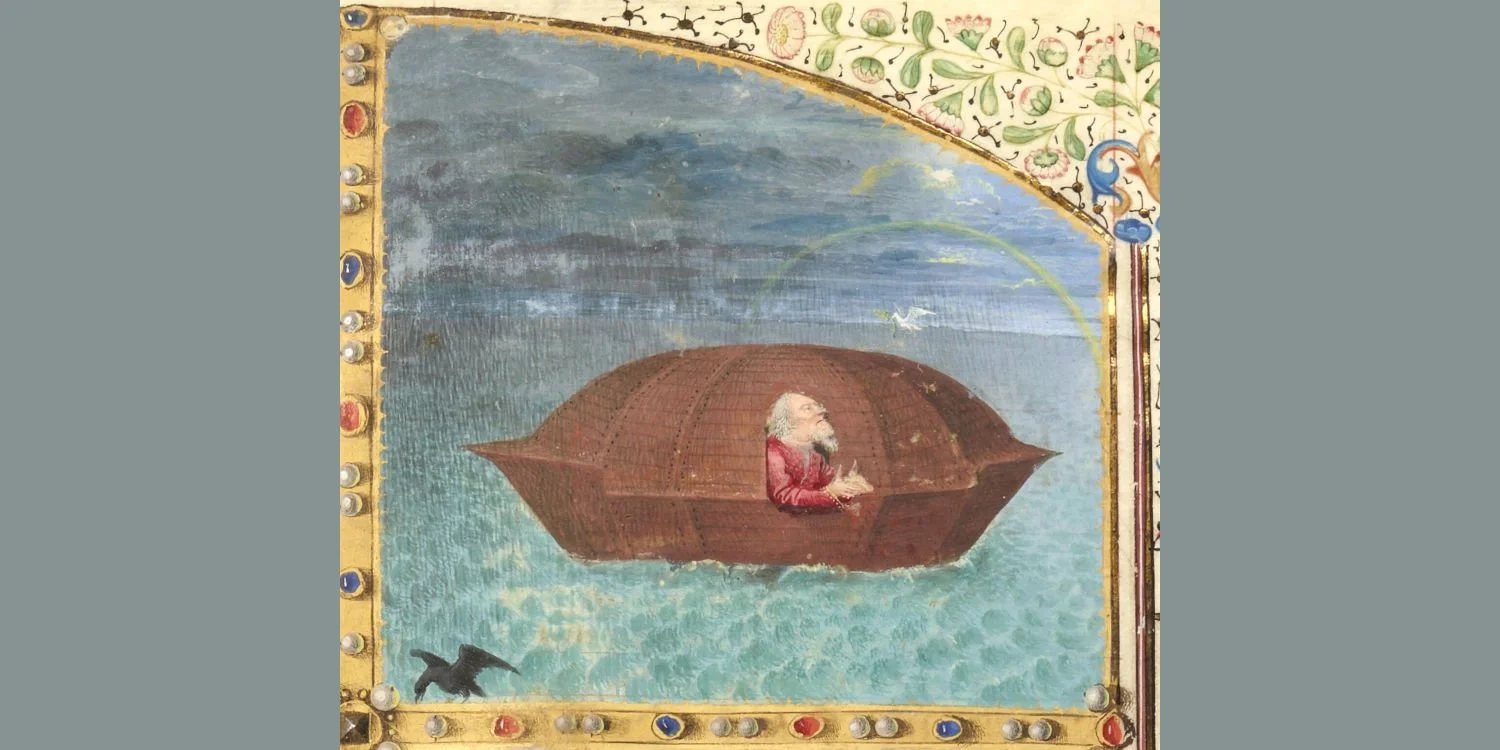

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

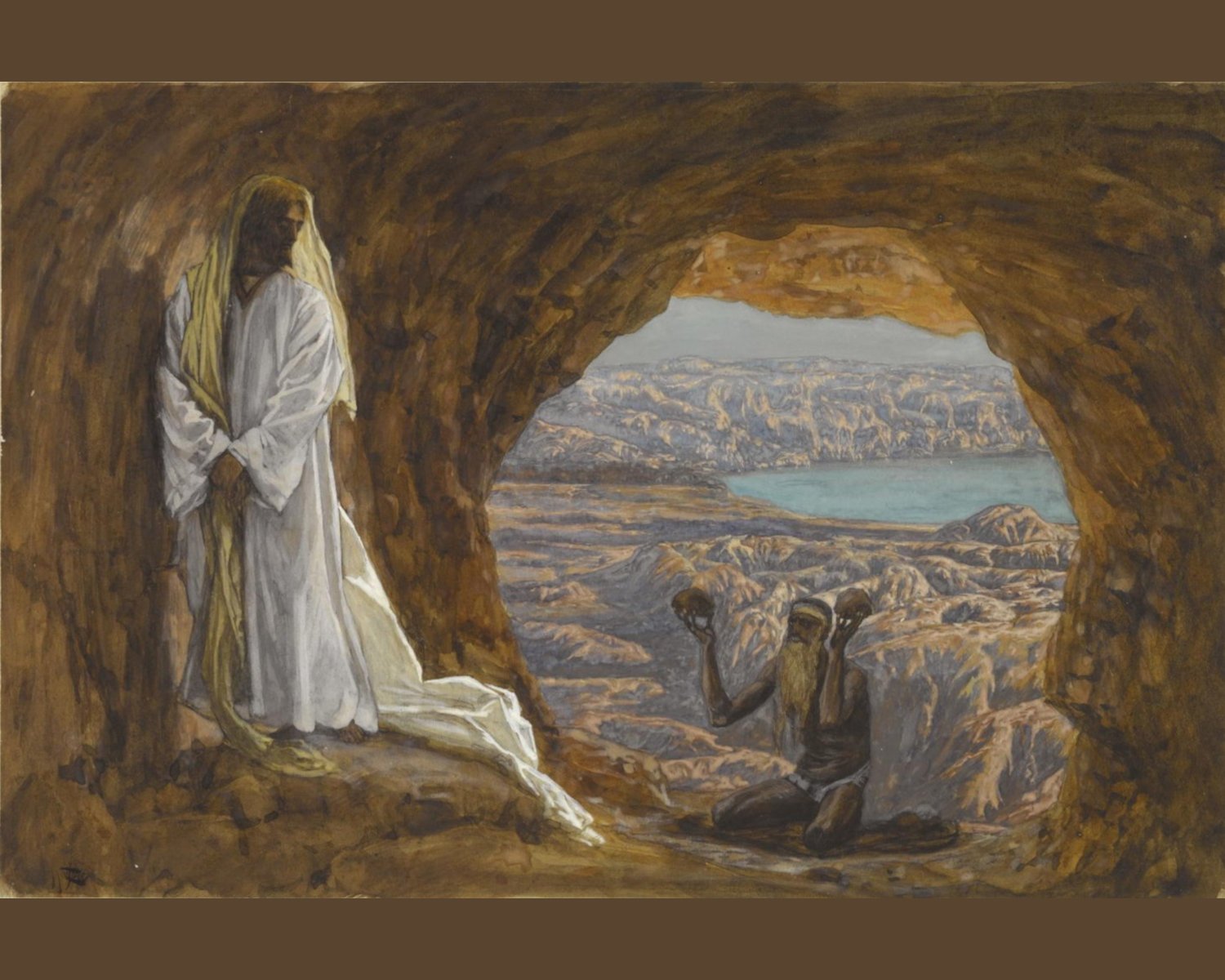

Christ in the Desert: A Devil of a Time

The Gospel according to St Luke tells the story of Jesus, revealed to be Son of God, led into the desert to be tested by the devil who does not give up easily.

The Gospel according to St Luke tells the story of Jesus, revealed to be Son of God, led into the desert to be tested by the devil who does not give up easily.

Ash Wednesday, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

Many of our readers are aware that the Church follows a three-year cycle for Sunday Scripture Readings. As Ordinary Time now gives way to the Season of Lent, I explore the Gospel for the First Sunday of Lent. Being in the “A Cycle,” the Gospel from Saint Matthew (4:1-11) seemed very familiar. Like much of Scripture, I knew that I had read about this passage, but I also felt certain that I had written about it. It is the story of Jesus following the revelation that he is the Son of God revealed at his Baptism in the Jordan. In Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus is led into the desert by the Spirit to face Satan and a series of temptations for which, if he failed, his redemptive mission would end before it even began. All three of the Synoptic Evangelists, Matthew, Mark and Luke, tell the same story but from different perspectives and traditions. Saint Mark’s version appears in Year B in just three lines of Scriptural text (Mark 1:12-15). The Gospel According to Saint Luke is the most theologically nuanced of the three. So even though in our current cycle, the version from Saint Matthew is used on the First Sunday of Lent, it is very similar to that of Saint Luke. So I have chosen the latter to present in exegesis form for our post this week.

+ + +

In my estimation, one of the best movies about Catholic life in America taking a wrong turn has been deemed by some to be a bit rough around the edges. Robert DeNiro portrays Los Angeles Monsignor Desmond Spellacy, and Robert Duvall is cast as his brother, LAPD homicide detective Tom Spellacy in the 1981 film, True Confessions. The film is from a novel of the same name by John Gregory Dunne based on the famous Los Angeles “Black Dahlia” murder case of 1947.

DeNiro’s character, Monsignor Desmond Spellacy is a priest of some prominence in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles in the late 1940s at the epicenter of the power politics of a Church beginning to succumb to the world in which it thrives. Amid corruption while being groomed to become the next Archbishop, the Monsignor nonetheless clings to an honest spiritual life just starting its inevitable fraying at the edges as he is drawn ever deeper into a tangled web of deceit.

Robert Duvall portrays his older brother, Tom Spellacy, an honest and dedicated — if somewhat cynical — L.A. homicide detective whose investigation of the murder of a prostitute brings him ever closer to the perimeter of an archdiocese circling the wagons of self preservation. The Church in America would see a lot more of this in the generation to come. Actor Charles Durning portrays the thoroughly corrupt owner of a large construction firm bidding for church building projects. About to be awarded Catholic Layman of the Year by the Archbishop of Los Angeles, he is also a person of interest in the murder investigation that a lot of powerful people want quietly covered up.

Those wanting to influence and sideline Tom’s investigation come up with evidence — a photograph. It depicts the murdered woman in a social scene with a few prominent people, one of whom, standing next to her, is Monsignor Desmond Spellacy, heir apparent of the archdiocesan throne.

The photograph is entirely bening, but it becomes for Tom Spellacy, as it was intended to be, evidence that the Monsignor knew the murdered woman. Many readers would be reminded by this today of the frenzied media fiasco that has been playing out to much fanfare, recriminations, and disgust about the Jeffrey Epstein files and the many lives, some innocent and some not-so-much, who are entangled by a mere photograph in Epstein’s posthumous web of corruption and deceit. In the hands of politicians on the eve of battle in the midtern national elections, such photographs have been honed as weapons of war in our bitter partisan politics. The film ends with the case solved, but Monsignor Spellacy banished to a small parish in the California desert, his hopes for political advancement in the Church destroyed.

Nonetheless, in the hands of media and various other entities, the photograph remains evidence and a legal and political quagmire for Detective Tom Spellacy tasked with an open and public investigation of a murder scene leading to political corruption. Tom knows that any pursuit of the case that involves this photograph will inevitably destroy the career and good name of his innocent brother. Tom struggles about what to do, but in the end he does the right thing. He pursues the truth of the matter wherever it leads.

The case is eventually solved and of course Monsignor Spellacy had nothing to do with the matter at hand. Someone is convicted (You have to watch the film to find out who). But in the moral sensitivies of the time, which was very much like our time, the photo with the murdered prostitute and the Monsignor becomes more enticing for the press than the murder itself. The photo ends up on the Front Page of the LA Times, and Monsignor Spellacy ends up where our Gospel passage begins: in the desert where he is exiled to a tiny parish in obscurity.

Being exiled in the desert is highly symbolic in Sacred Scripture. It has ancient roots in the Book of Leviticus. This book is composed of liturgical laws for the Levitical priesthood reaching back to 1300 BC as Moses led his people through a forty-year period of exile in the Sinai desert. Some of the ritual accounts it contains are far more ancient.

In a recent Christmas post, “Silent Night and the Shepherds Who Quaked at the Sight,” I wrote that the troubles of our time are the manifestation of spiritual warfare that has been waged in the world since God’s first covenant bonds with us. Before this covenant relationship, we were doomed. Since the covenants of God there is hope for us. We remain oblivious to spiritual warfare to our own spiritual peril. As I have written many times, we now live in a vulnerable time in God’s covenant relationship with us. The Birth of the Messiah and his walking among us are equidistant in time between our existence now in the 21st Century AD and Abraham’s first encounter with God in the 21st Century BC.

Our Day of Atonement Begins

The Gospel according to St Luke (4:1-13) is also set in the desert as the Day of Atonement begins for all humankind. Revealed in Baptism as the Son of God …

“Filled with the Holy Spirit, Jesus returned from the Jordan and was led by the Spirit into the desert for forty days to be tempted by the devil.”

— Luke 4:1

The scene has roots in an ancient ritual for the Day of Atonement described in Leviticus 16:5-10. Aaron, the high priest …

“Shall take from the congregation of the people of Israel two male goats for a sin offering .... Then he shall take the two goats and set them before the Lord at the tent of meeting; and Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats, one for the Lord and the other lot for Azazel. And Aaron shall present the goat upon which the lot fell for the Lord, and offer it as a sin offering, but the goat upon which the lot fell for Azazel shall be presented alive before the Lord to make atonement over it, that it may be sent away into the desert wilderness to Azazel …”

— Leviticus 16:5,7-10

This describes the ritual for purification known in Hebrew as Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement, from Leviticus Chapter 16. The ritual reaches far beyond Moses into the time of God’s covenant with Abraham some 2000 years before the Birth of the Messiah.

There are two goats mentioned in the ritual: One for sacrifice, to Yahweh, and the other — the one bearing the sins of Israel — is “for Azazel.” This name appears only in Leviticus 16 and nowhere else in Scripture except here in the Gospel of Luke and in some of the apocryphal writings found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. One of them is the Apocryphal Book of Enoch, the name of a figure in Genesis who “walked with God” and “was taken up from the Earth.” As such, Enoch is presented in the genealogy of Jesus in Luke (3:37), and thus was spared the deluge of Noah and the destruction intended for all mankind.

The name Azazel is believed by most scholars to be the name of a fallen angel and follower of Satan. Azazel haunts the desert wilderness. Some scholars believe Azazel to be the being referred to as “the night hag” in Isaiah 34:14.

The Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible called the second goat “caper emissarius,” (“the goat sent out”). An English translation rendered it “escape goat” from which the term “scapegoat” has been derived. A scapegoat is one who is held to bear the wrongs of others, or of all. The symbolism in the Gospel of Jesus being led by the Spirit into the desert to face the devil is striking because Jesus is to become, by God’s own design, the scapegoat for the sins of all humanity.

In the Gospel for the First Sunday of Lent, Jesus is described as “filled with the Holy Spirit.” This term appears in only three other places in Scripture, all three also written by Saint Luke. In the Book of Acts of the Apostles (6:5) Stephen, “filled with the Holy Spirit” was the first to be chosen to care for widows and orphans in the daily distribution of food. Later in Acts (7:55) Stephen, “filled with the Holy Spirit gazed into heaven and saw the glory of God” as he became the first Martyr of the Church.

The witnesses who approved of the stoning of Stephen “laid their cloaks at the feet of a young man named Saul” (Acts 7:58) whose radical conversion to become Saint Paul would build the global Church.

Also in Acts (11:24) Barnabas is filled with the Holy Spirit as he founded the first Church beyond Jerusalem for the Gentiles of Antioch. The sense of the term “filled with the Holy Spirit” in Saint Luke’s passages alludes to the hand of God in our living history.

In our first Sunday Gospel for Lent, Jesus, filled with the Spirit, “having returned from the Jordan,” is led by the Spirit for forty days in the desert wilderness. The Gospel links this account to his Baptism at the Jordan at which he is revealed as “Son of God.” This revelation becomes, in the desert scene, a diabolical taunt, and knowing that Jesus has fasted becomes the devil’s first temptation: “If you are the Son of God, turn this stone into bread.” Jesus thwarts the temptation and the taunt with a quote from the Hebrew Scriptures (Deuteronomy 8:3), “Man does not live by bread alone but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.”

The symbolism is wonderful here. Like the Father in the Parable of the Prodigal Son — also from Luke (15:11-32) — God had two sons. In the Book of Exodus (4:21-22) Israel is called God’s “first-born son”:

“The Lord said to Moses, ‘When you go back to Egypt, see that you do before Pharaoh all the miracles which I have put in your power, but I will harden his heart so that he will not let the people go. And you shall say to Pharaoh, ‘Thus says the Lord, Israel is my first-born son, and I say to you, let my son go that he may serve me. If you refuse to let my son go, I will slay your first-born son’.”

It was the fulfillment of this command of God that finally broke the yoke of slavery and caused Pharaoh to release Israel from bondage. But, as the Parable of the Prodigal Son implies of the Prodigal Son’s older brother, Israel was not faithful to the Word of God, and spent forty years wandering in the desert as a result of its infidelity.

In the Gospel of Luke, the Second Person of the Most Holy Trinity assumed the humanity of the first son, and was led by the Spirit into the desert to save us in the Second Exodus, our release, through the Death and Resurrection of the Son of God, from the eternal bondage of sin and death.

Clerical Scandal and the Scandal of Clericalism

The second temptation is the lure of political power. In a single instant, the devil showed Jesus all the kingdoms of the world and said, “I shall give you all this power and glory for it has been handed over to me… all this will be yours if you worship me.” This has been the downfall of many, including many in our Church. Jesus again quotes from Scripture, “It is written, you shall worship the Lord your God and serve him alone” (Deuteronomy 6:13). This Gospel revisits the lure of political power immediately after the Institution of the Eucharist:

“A dispute arose among them, which of them was to be regarded as the greatest. And he said to them, ‘The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them, and those in authority over them are called benefactors. But not so with you. Rather let the greatest among you become as the youngest, and the leader as one who serves… I am among you as one who serves.”

— Luke 22:24-26

The Greek in which this Gospel was written used for the word “leader” the term “hēgoumenos.” Its implication refers especially to a religious leader. The Letter to the Hebrews (13:7) uses the same Greek term for “leaders,” and it is not their Earthly power which is to be emulated, but their faith to the extent to which they reflect Christ:

“Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God, consider the outcome of their life, and imitate their faith. Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever.”

— Hebrews 13:7-8

Though it doesn’t generate the media’s obsession with sexual scandals, hubris and self-centered aggrandizement have been a far greater problem in our Church, and are the underlying catalyst for almost all other scandals, sexual, financial, and reputational. This culture has led Church leaders into the temptation of Earthly Powers, and too many have been eager participants. Some refer to this as “clericalism,” and in my opinion the best commentary on it was a brief article by the late Father Richard John Neuhaus in First Things entitled, “Clerical Scandal and the Scandal of Clericalism.”

The Payment of Judas Iscariot

Catholicism in America thrived when it had to earn its dignity. Once it became politically accepted, it went on in this culture to become comfortable, and its leaders (“hēgoumenos”) perhaps a bit too comfortable. Religious authority and the sheer masses of believers spelled political power. The pedestals upon which we stood grew in height with every clerical advance, and our bishops stood upon the highest pedestals of all with palatial trappings more akin to the courts of Herod and Caesar than the Cross of Christ the King, the same yesterday, today, and forever.

It is no mystery why, as the height of our pedestals grew, so did our scandals. This is perhaps why Jesus offered to us the way to pray “Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.” It is because he alone could be led by the Spirit into the desert of temptation and emerge without dragging along behind Him the evil He encountered there.

As the last temptation of Christ unfolded in the Gospel for the First Sunday of Lent, it is now the devil, in a final effort, who dares to quote and distort the Word of God. He led Jesus to Jerusalem, and to the parapet, the highest point of the highest place, the Temple of Sacrifice. And now comes his final taunt:

“If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down from here, for it is written, ‘He will give his angels charge of you, to guard you,’ and ‘On their hands they will bear you up, lest you strike your foot against a stone’.”

— Luke 4:9-11, quoting Psalm 91

This devil of the desert takes up the argument of Jesus, the Word of God, quoting Psalm 91 (11-12). The taunt to test God and “go your own way” is far deeper than the mere words convey. In Jerusalem, the devil will take hold of Judas Iscariot (Luke 22:3) leading to the trial before Pilate and the Way of the Cross. In Jerusalem, the powers of darkness, first encountered here in the desert, are mightily at work: “This is your hour, and the power of darkness.” (Luke 22:53)

The Church in the Western world has entered a time of persecution but thus far the institutional response — having traded the Gospel for “zero tolerance” in a quest for scapegoats to cast out into the desert to Azazel — does not bode well for the faith of a Church built upon the blood of the martyrs.

Perhaps, as the Spirit leads us into this desert, it is our vocation, and not that of our leaders, that is essential. Perhaps it is not clerical reform that is needed so much as a revolution — a revolution of fidelity that can only be lived and not just talked about. We will not find the Holy Spirit in a revolution that manifests itself in blessing sin or in any politically correct acquiescence to same-sex unions that some now call the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony, and other moral distortions of our time. Those who abandon their faith in a time in the desert were leaving anyway, just waiting for the right excuse. To use the behavior of leaders to diminish and then abandon the Sacrament of Salvation is to cave to the true goal of Azazel. He could not lure Christ from us, but he can lure us from Christ and he is giving it a go.

The devil finally gives up in the desert scene of the Last Temptation of Christ in Luke Chapter 4. But the devil is not quite done. Luke’s Gospel tells that he will return “at a more opportune time.” Satan finds that time not in an effort to test Jesus, but rather to test his followers. He targets Judas Iscariot in the last place we would ever expect to find the devil: “Satan at The Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light.”

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this Ash Wednesday post. You may also like these other posts from Beyond These Stone Walls as we proceed through Lent:

Pope Francis Had a Challenge for the Prodigal Son’s Older Brother

A U.S. Marine Who Showed Me What to Give Up for Lent

Satan at The Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light

Behold the Lamb of God Upon the Altar of Mount Moriah

We presently have 39 titles in our collection of Scriptural posts, The Bible Speaks.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

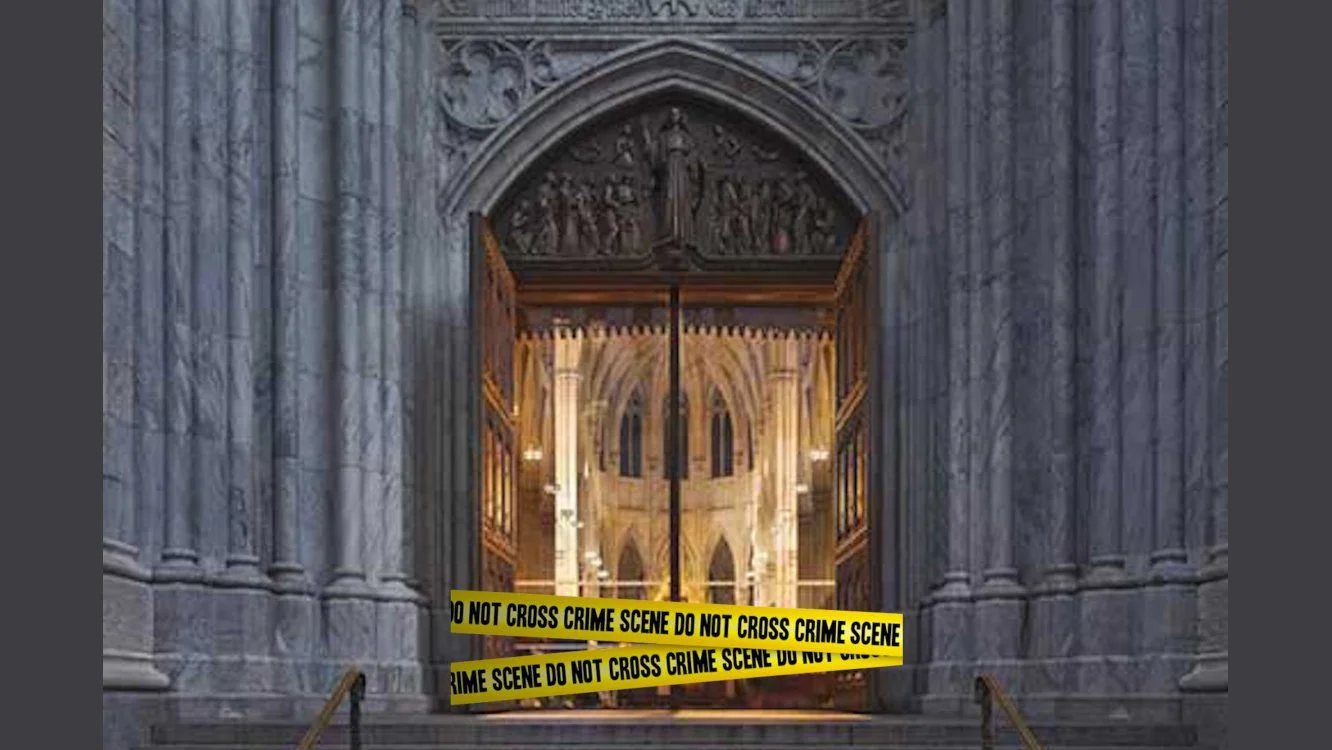

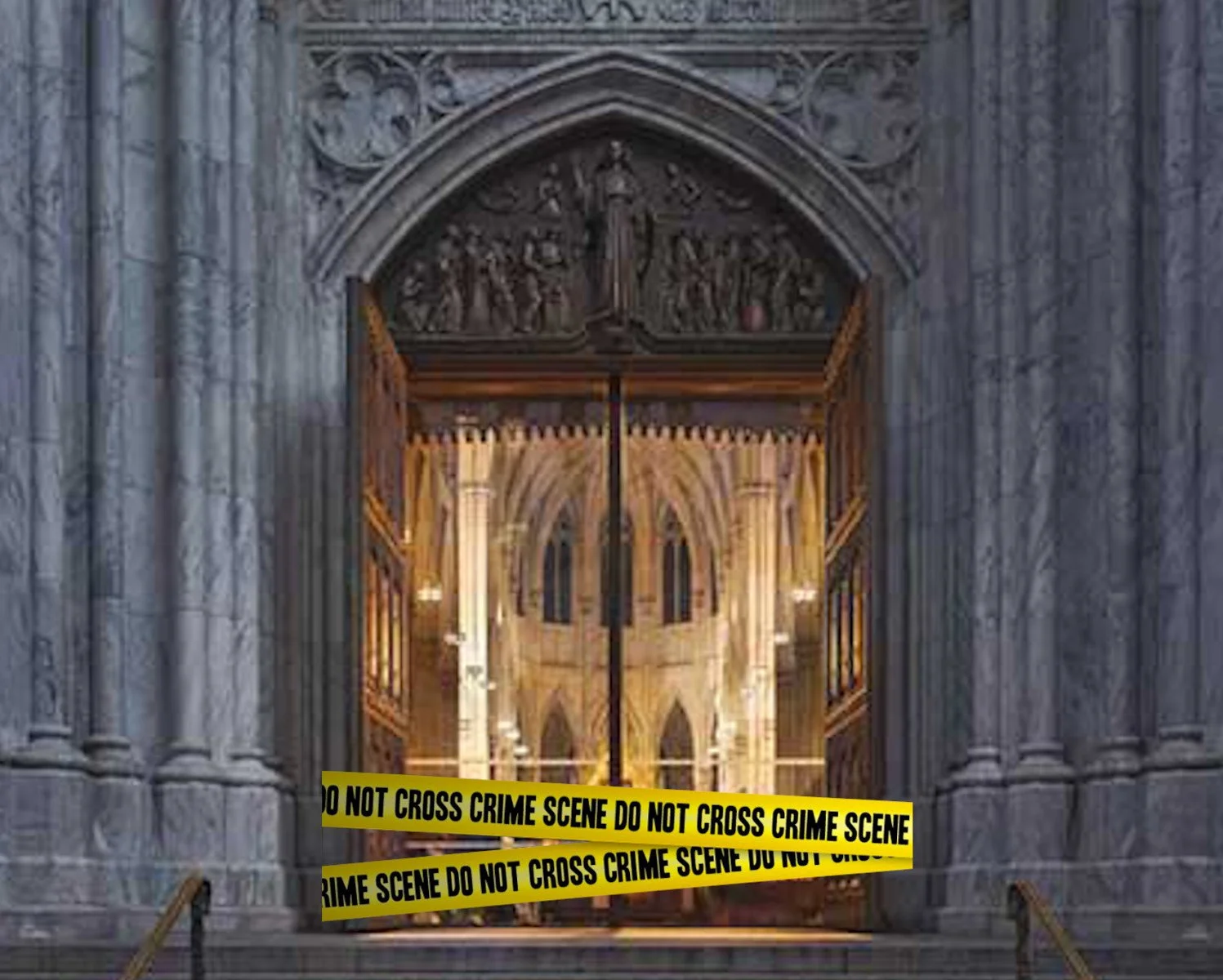

Latin Mass and Altar Rails Are Under Siege in North Carolina

Citing unity, the Bishop of Charlotte, North Carolina imposed a ban on altar rails and kneeling and severely further restricted access to the Traditional Latin Mass.

Citing unity, the Bishop of Charlotte, North Carolina imposed a ban on altar rails and kneeling and severely further restricted access to the Traditional Latin Mass.

February 11, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

In its “Year in Review” feature dated December 28, 2025, the National Catholic Register published “The Top 25 Register Stories of 2025.” AI tools were used to generate summaries and rank the stories based upon online page views, which were then reviewed by an editor. The result was a visually striking account of Catholic interests over the previous year. Two of the entries were perplexing, however.

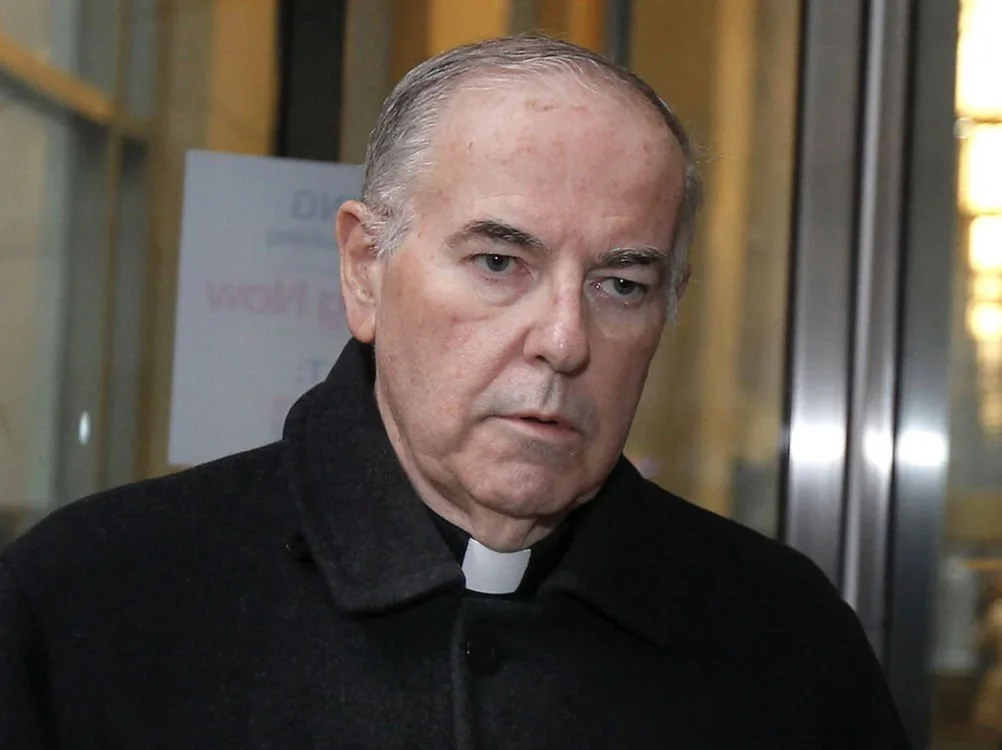

Item #17 on the list featured a photo of Charlotte, North Carolina, Bishop Michael Martin with the headline, “Charlotte Liturgy Controversy Heats Up After Bishop’s Proposed Ban of Latin, Altar Rails Leaked.” The segment was written by Register Columnist Jonathan Liedl who added, “The Charlotte Diocese ignites a firestorm in 2025 as Bishop Michael Martin’s leaked proposal to ban Latin and altar rails stirs international debate. Critics argue the norms contradict Vatican II’s teachings, while supporters claim they aim for liturgical unity. This controversy marks the first major liturgical clash under Pope Leo XIV, positioning Charlotte, North Carolina, as a litmus test for the future Catholic worship.”

In another Register column appearing adjacent to the above story was Item #20, which presented a polar opposite view: “Communion Rails Return as Churches Embrace Beauty and Reverence,” presented by Register Columnist Joseph Pronechen who added, “In 2025, Catholic parishes across the U.S. embrace a revival of altar rails, transforming the reception of Communion into a more reverent experience. Joseph Pronechen highlights how this return fosters a sacred atmosphere, encouraging congregants to kneel and reflect on the significance of the Eucharist. As communities rediscover this liturgical beauty, they deepen their connection to faith and tradition marking a profound shift in worship practices.”

I could not help but notice further context in a mid-September, 2025 Catholic News Agency report on new regulations on Catholic practice in China. This time, the ban came from the Chinese Communist Government’s State Administration for Religious Affairs. It imposes a ban on any form of online evangelization. It is imposed on all Catholic priests in China, both foreign and domestic. The ban also requires that all clergy express their “love for the Motherland,” and their support for Chinese Communist Party leadership and its socialist system.

Faith leaders in China are also banned from “preaching and performing religious rituals to live broadcasts, videos, or online meetings,” and are specifically banned from evangelizing or educating minors on the Internet, and from raising funds in support of their ministries.

Lest Catholics take any of this personally, the Chinese Communist government has also taken upon itself the absolute right to select the next Dalai Lama supplanting centuries-old traditions.

I do not in any way equate what is happening under State authority in China with what is happening under religious authority in North Carolina or elsewhere in America, but the timing of these endeavors is striking. In the matter of the oppression of faithful Catholics in China, it seems that the motive of the Chinese Communist Party in issuing their agenda at this time came in response to a September 18, 2025 interview with Pope Leo XIV.

Pope Leo has reportedly stated that he had been listening to a significant group of Chinese Catholics who faced difficulty in living their faith freely. In the interview, he reportedly signaled that he may be open to future changes in the Vatican’s controversial agreement with China, according to the Catholic News Agency.

Cardinal Pell’s Concern About Schismatic Agendas

Catholics have come to expect suppression of legitimate faith experience from Communist regimes, but suppression by Church hierarchy of previously sanctioned forms of worship seems entirely new. For the Sensus Fidelium, the lived experience of the faithful across generations, it can also be deeply troubling and spiritually wounding.

I have come to appreciate the candor and spiritual integrity of prison writing from the ranks of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Father Walter Ciszek, Father Alfred Delp, and most recently, the late Cardinal George Pell. Writing from prison with very limited opportunities for dialogue and in-depth research means writing almost exclusively from one’s own mind, heart and soul. The three-volume Prison Journal of George Cardinal Pell is a treasure trove of unfiltered candor and spiritual integrity.

While reading his Prison Journal, Volume 2 (in which, for full disclosure, my own writing occupied several pages) Cardinal Pell wrote candidly of his concern for the modern direction of the Church. Among his deepest concerns was the growing possibility of a progressive-driven schism. He cited a September 17, 2019 Catholic Culture entry by Philip Lawler, “Who benefits from all this talk of schism?”

Lawler argued that the prospect of a schism was remote, but became less so during the papacy of Pope Francis and the Synod on Synodality. Francis had spoken calmly about such a prospect saying that he is not frightened by it, something that both Lawler and Pell found to be concerning in and of itself. Cardinal Pell added that The New York Times had been writing about the prospect of a progressive German Catholic schism by “the John Paul and Benedict followers in the United States, the Gospel Catholics.” He observed that Lawler’s diagnosis was correct and pointed out that, “the most aggressive online defenders of Pope Francis realized they cannot engineer radical changes they want without precipitating a split in the Church. So they want orthodox Catholics to break away first, leaving progressives free to enact their own revolutionary agenta.” (Prison Journal Vol. 2, pp 214-215 — emphasis added)

In light of this, it comes as no surprise that progressive bishops are pushing for divisive restrictions on the Traditional Latin Mass and other traditional expressions of the faith, such as kneeling and altar rails. These efforts should come as no surprise to faithful Catholics. Embracing and promoting fidelity with respect for tradition has never been more urgent. Faithful Catholics must never accede to the desired end that progressives seek. Handing the Church over to that agenda would leave “Satan at the Last Supper” while Jesus is removed from the room.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: We hope you will take time to read and share this important post, and along with it a companion post at our Voices from Beyond feature by Aloonsri Paokumhang. Aloonsri is a first-generation American citizen and the daughter of immigrants from the Kingdom of Thailand. She is a convert to our faith, and a most articulate writer about current matters facing the Church. It is Aloonsri whom I had in mind when I wrote that suppression of the Sensus Fidelium, the lived experience of faithful Catholics, can be deeply troubling and spiritually wounding.

You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Priests in Crisis: The Catholic University of America Study

My Father’s House Has Many Rooms. Is There a Room for Latin Mass?

Pell Contra Mundum: Cardinal Truth on the Synod

The Once and Future Catholic Church

+ + +

One More Note: Diane Montagna is an American journalist acccredited to the Holy See. She has written for Aleteia, LifeSite News, and L’ Osservatore Romano. Ms. Montagna has compiled a well informed critique published in July 2025 entitled:

EXCLUSIVE: Official Vatican Report Exposes Major Cracks in Foundation of Traditionis Custodes

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

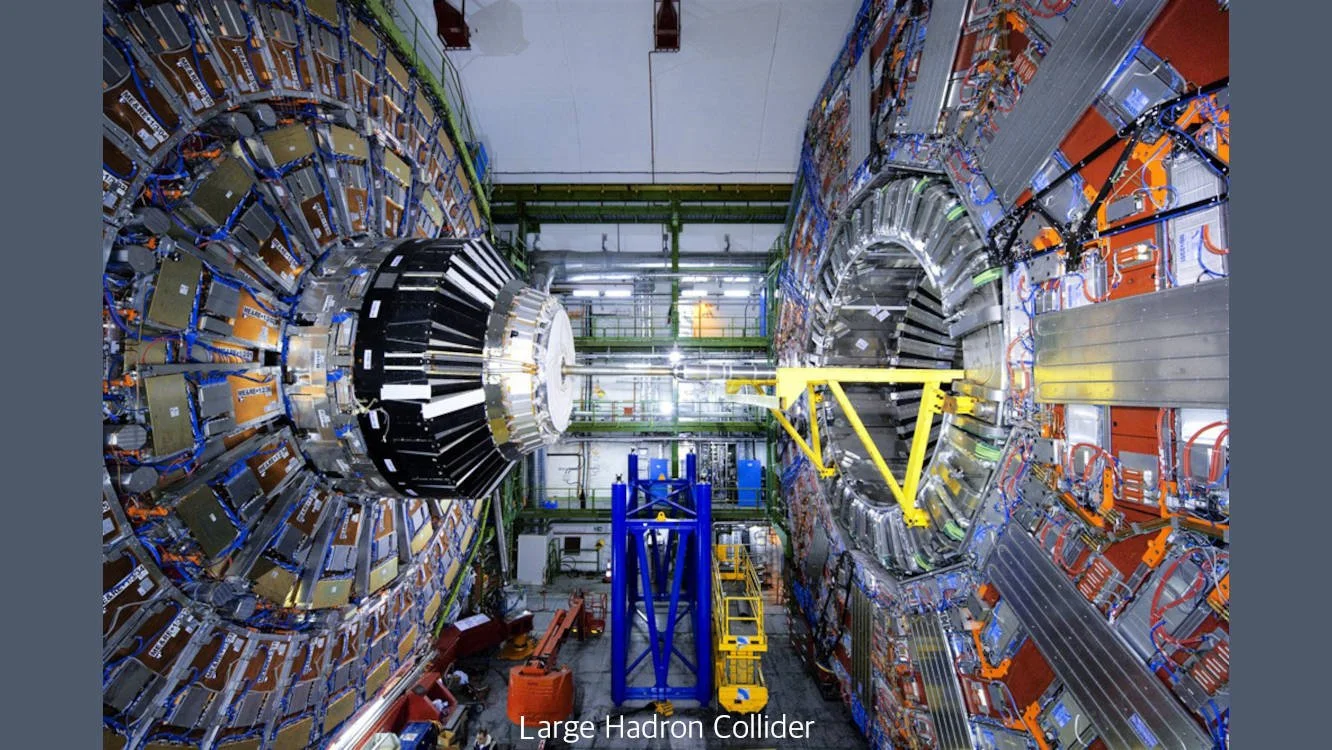

The Higgs Boson God Particle: All Things Visible and Invisible

In 2012, scientists at the Large Hadron Collider detected the elusive Higgs boson, a subatomic particle dubbed the “God Particle” explaining the origin of matter.

In 2012, scientists at the Large Hadron Collider detected the elusive Higgs boson, a subatomic particle dubbed the “God Particle” explaining the origin of matter.

February 4, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

“Two Higgs boson particles walked into a bar. Over drinks one said, ‘I hear Stephen Hawking bet $100 that we don’t exist. What if he’s right?’ The other replied, ‘No matter!’ ”

Get it? No matter? Get it? Well, hopefully you will in a few minutes. I didn’t get it either until I did some heavy-duty reading.

If this post is creating a touch of déjà vu, a sense that you have seen it before, it’s because you probably have. Something quite unusual happened here at this blog in recent weeks. In the earliest days of this blog in 2010, I was contacted by a reader in Australia about a new book by physicists Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow entitled The Grand Design (Bantam Books, 2010). The letter writer was concerned that media outlets in Australia and around the world were citing aspects of the book out of context in an attempt to demonstrate that Stephen Hawking declared that God does not exist. That was a faulty interpretation and the reader wanted me to set the record straight. It was a tall order, but I had time on my side to ponder and present a contrary point of view. So on October 6, 2010, we published “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?”

A lot of work went into that post, but to my chagrin it was met by most of our readers with a yawn the size of a giant black hole. Fifteen years later, someone (not me) submitted that post to an advanced artificial intelligence model requesting an analysis of it. The results were then read to me by our Editor. AI scoured the Internet and then referred to me as “a Catholic priest with a background in science” while singling out that post as “a significant example of bridging the gap between science and faith.”

So of course, I thought that was the nicest thing any AI had ever said about me (There was very little to compare it to.). Given this new interest in a bridge between science and faith, I decided to haul out this 15-year-old post and rehabilitate it for a new audience. On July 30, 2025, we republished “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” The result was mind boggling, but it was not immediate. A few months later that post started showing up in our stats and then it began a viral spread. By January it was outpacing my regular weekly posts in popularity. And then by mid-January it spread all over the world in unprecedented numbers for this blog.

I cannot pretend to know why this happened. I do not understand the global attention to this one post on the space-time continuum. Perhaps my only conclusion is that when I post a bomb, just wait 15 years and post it again.

The Discovery

There is another post of mine that also bridges the gap between science and faith. I do not have an explanation for why or how, but another of my posts, this one from 2012, also began to show up in unusually large numbers with that other post. I have long wanted to repost this one with some updated information so that those who are currently reading and spreading it can see the updated version. It is “The Higgs Boson God Particle: All Things Visible and Invisible.”

I first wrote it in September 2012. It, too, was met with a rather extended yawn, but today it shows up often and everywhere. It profiles the work of the late physicist Peter Higgs who rose to prominence in the scientific community in 1964 when he theorized that the Higgs boson exists as a necessary subatomic particle which explains the existence of matter. After my post was first published, the Higgs boson was experimentally demonstrated again and Peter Higgs was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. He died on April 8, 2024 at the age of 94 knowing that his life’s work was a major addition to the scientific understanding of the Universe.

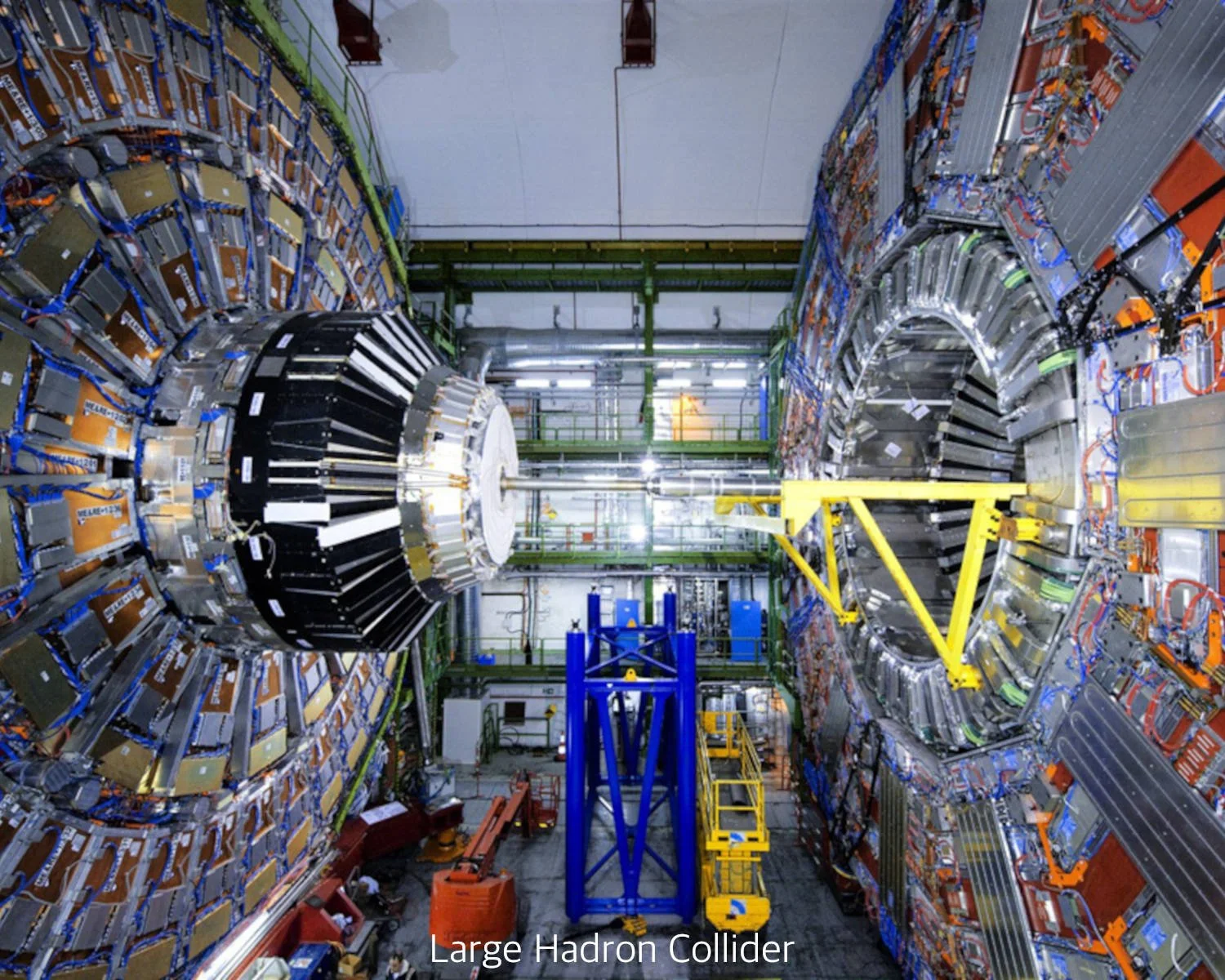

A boson in physics is a component of subatomic particles such as protons and photons, which exist in every atom of matter. As a class of particle, a boson is so-called in honor of Indian physicist, Satyenda Nath Bose, who collaborated with Albert Einstein. The existence of a then-theoretical Higgs boson resolved a puzzle in the Standard Model of physics, a widely accepted model for how particles interact. The thinking in the Standard Model was that particles such as photons — particles of light — have no mass. They should move throughout the Universe unhindered. The mathematics of the Standard Model explained successfully the existence of particles, but not mass or matter. The Higgs boson proposed by Peter Higgs in 1964 was an explanation for how particles could attain mass, and thus bring into being a Universe filled with matter that we can see or otherwise detect.

CERN, the European agency for nuclear research, operates and oversees the Large Hadron Collider. It is a donut-shaped laboratory 27-miles in circumference on the French-Swiss border. Two beams of protons were set on a collision course moving at close to the speed of light. Their collision resulted in an explosion that recreated the conditions of The Big Bang, the scientifically accepted origin of our Universe. During the collision, a supercomputer detected the presence of the Higgs boson particle and a Higgs field for a trillionth of a second. It was the first time its existence had ever been established in a laboratory

On July fourth in 2012, physicists announced that they had a momentary glimpse of the elusive Higgs boson, the subatomic particle long theorized to exist, and without which matter itself would not exist. The physicists who reported that they only found “evidence” of the Higgs boson were just being careful scientists. The discovery had a 99.9999% rate of certainty. There is no doubt left. The Higgs boson does indeed exist and that experiment has since been ratified.

So what exactly does this mean? Many scientists grimaced every time someone in the news media referred to this discovery as “the God particle.” Using science out of context to debunk religious faith is a favorite pastime of some in the media, but the reverse should also not happen.

I took a hard look at the interaction between faith and science in “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” After publication of The Grand Design, some in the news media speculated that Hawking’s book demonstrated that gravity — and not God — is responsible for the creation of the Universe. My conclusion was simply that Stephen Hawking has thrown in with the wrong “G,” and the pundits misreading his book have confused the tools of God with God. I cited in that post a vivid example. If you were an archeologist digging in ruins in Florence, Italy and you discovered a worn chisel that was used by Michelangelo to create the Pietà, one of the most celebrated examples of sculptured marble in art history, would you then conclude that Michelangelo did not create the Pietà, his chisel did?

What I find most interesting about the recent discovery is that the Higgs boson appears nowhere in Stephen Hawking’s The Grand Design. His analysis of the science of cosmology omitted it entirely. In fact, two decades ago Stephen Hawking wagered $100 that the Higgs boson would never be detected. He lost the bet.

The discovery of the Higgs boson is a big deal in science because it presents a purely scientific explanation for how matter exists, but not why. The model for creation it implies is that a primordial atom exploded in what we call The Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago. As the explosion cooled, a force known as a “Higgs field” — which contained the Higgs boson — was formed and permeates the Universe. As other particles interacted with this field, they acquired mass allowing gravity to bring particles together. It acted sort of like a dam slowing particles so that they would mass together. The result was matter as we know and see it — everything from stars to us. It’s sort of the yeast with which God bakes bread.

A Day Without Yesterday

The Higgs boson was detected by the Large Hadron Collider’s super computers in July 2012 for a fraction of a trillionth of a second. The tiny collision sent particles in every direction producing the energy equivalent to 14 trillion electron volts and blistering temperatures. The collision recreated a tiny model of the instance of The Big Bang. Some theorize that it was the presence of the Higgs boson particle within the primordial atom that caused The Big Bang itself, and the explosion of all matter in the Universe.

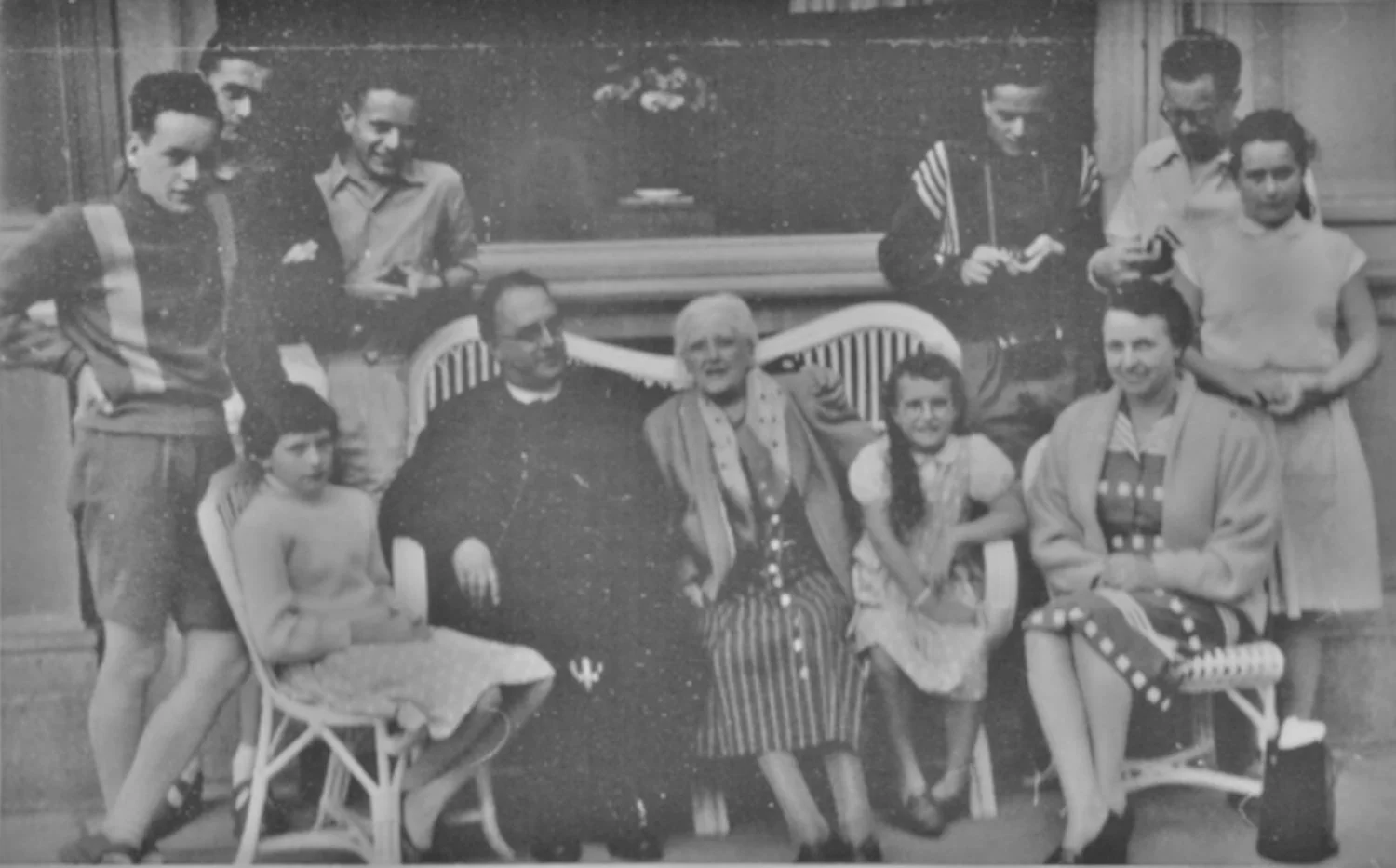

I find this all fascinating, but what is most fascinating is that the entire model was first mathematically predicted, and then demonstrated to even Albert Einstein’s satisfaction, by a Catholic priest. I wrote of the Belgian priest and physicist, Father Georges Lemaitre, in “A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and the Big Bang. As a result of that post and others related to it, I began a correspondence with Father Andrew Pinsent, who prior to priesthood had been a physicist at CERN. We collaborated on a very special post, “Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang.”

If ever you bristle about the typical anti-Catholic mythology that religion attempts to hold back science, remember that the originator of all the science behind this model of creation was a Catholic priest, and many of the great scientists of his time did everything they could to suppress his ideas. They failed because they could not successfully refute either his faith or his science. In the end, even Einstein bowed to Father Lemaitre, declaring that his model was “the most satisfactory explanation of creation I have ever heard.”

Pope Pius XII applauded Father Lemaitre’s discovery of The Big Bang because it challenged the acceptable science of the time which claimed that the Universe was not created, but always existed and is eternal. Einstein later acknowledged that his “Cosmological Constant” was his greatest error.

Perhaps the greatest miracle of all for me was receiving the photo below of Pornchai Moontri’s Godfather, the late Pierre Matthews, whose mother was a close friend of Father Lemaitre, who became Pierre’s Godfather. The odds that my roommate in Concord, New Hampshire would turn out to be the Godson of a man whose own Godfather discovered the Big Bang are as great as the odds of the Big Bang itself.

Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at City University of New York, wrote a brilliant and (unlike this post) brief commentary about the Higgs boson for The Wall Street Journal (“The Spark That Caused the Big Bang,” July 6, 2012). Professor Kaku wrote:

“The press has dubbed the Higgs boson the ‘God particle,’ a nickname that makes many physicists cringe. But there is some logic to it. According to the Bible, God set the Universe in motion as He proclaimed ‘Let there be light.’”

“So why did the Higgs boson particles hurry to church?

Because Mass could not start without them.”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: For open minds and enlightened souls bridges are taking shape between the realms of science and faith. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?

Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang (a must-read by Father Andrew Pinsent)

The James Webb Space Telescope and an Encore from Hubble

For Those Who Look at the Stars and See Only Stars

+ + +

And then there was this: xAI Grok on Higgs Boson, God Particle, Science and Faith.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Covenants of God from Genesis to the Book of Revelation

A Covenant is a kinship bond between two parties. It is the master-theme of Salvation History in which God draws believers into a family relationship with Himself.

A Covenant is a kinship bond between two parties. It is the master-theme of Salvation History in which God draws believers into a family relationship with Himself.

January 28, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

“Testament” is the name given to the two principal divisions of the Christian Bible. It is derived from the Latin, “testamentum,” translated from the biblical Greek term, “diathēkē,” which is more properly translated as “Covenant.” In fact, the traditional designations of the biblical “Old Testament” and “New Testament” were inspired by Saint Paul’s distinction between the Old Covenant and the New Covenant in 2 Corinthians 3:6,14:

“Our sufficiency is from God who has qualified us to be ministers of a New Covenant, not in written code but in the Spirit; for the written code kills, but the Spirit gives life … not like Moses who put a veil over his face so that the Israelites might not see the end of the fading splendor.”

This cryptic verse from Saint Paul requires some deeper analysis. I touched on it once in my post, “A Vision on Mount Tabor: The Transfiguration of Christ.”

Peter had just declared at Caesarea Philippi that Jesus is the Christ (Luke 9:18-22). As though to demonstrate the truth of that declaration, the face of Jesus shone momentarily like the sun. The story recalled for Hebrew hearers of the Gospel the account of Moses at Mount Sinai as he received the Decalogue, the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:1-17). Being in the presence of the Lord caused the face of Moses to shine brilliantly causing Aaron and other Israelites to fear approaching him. Moses then placed a veil over his face.

Some 3,000 years later, Saint Paul interpreted this as a sign that the Sinai Covenant is destined to fade so that the New Covenant in Christ may fulfill it. I will address this in the Sinai Covenant below. The point Saint Paul makes is that the glory of Jesus in the Transfiguration does not look back upon the Sinai Covenant for meaning, but rather the other way around. It is a statement from Saint Paul that the Old Covenant looks forward, and points us looking forward to the New. The Gospel of Matthew Transfiguration account gives symbolic witness to this (Matthew 17:8): On Mount Tabor, “When they lifted up their eyes, they saw no one but Jesus only.” Saint Augustine in the Fifth Century offered a summation of the meaning of this passage: “The New Testament lies hidden in the Old and the Old Testament is unveiled in the New.”

In his brilliant “Overview of Salvation History,” an introductory essay in the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, John S. Bergsma, PhD, identifies something interesting and unique in Catholic spiritual tradition. It is the concept of “Divine filiation,” the notion, unique in religion, that elevates us as sons and daughters of God by adoption.

In Islam it is considered blasphemy to claim to be a child of God. In Judaism of the Old Covenant it is but a metaphor, not meant literally, but figuratively and symbolically. In Classical Buddhism it is simply irrelevant because individual personhood is itself an illusion remedied, for the Buddhist believer, by cycles of reincarnation.

Only Christianity holds that we become — literally become — sons and daughters of God the Creator, our Father and the source of all fatherhood. This is identified in Saint Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians (3:15):

“For this reason I bend my knees before the Father from whom every family in Heaven and on Earth is named.”

“Abba, Father” is an Aramaic and English term that occurs three times in the New Testament. The first time (Mark 14:36) quotes Jesus directly:

“Abba, Father, all things are possible to you; remove this chalice from me; yet not what I will, but what you will.”

The term was then reiterated by Saint Paul (Romans 8:15 and Galatians 4:6). “Abba” is an Aramaic term that reveals an especially familiar bond between father and child. Aramaic, closely related to Hebrew, was the common language in the Near East from about 700 BC to 600 AD. Each time “Abba” was used in the New Testament it was paired with the Greek equivalent of “Father.” This gave us the English translation, “Abba, Father” denoting the connection with Jesus as children of God.

After the fall of man, the only remedy for broken Covenants was for God to adopt us, and for us to strive to live up to that adoption. We strive still.

The Covenants of Adam, Noah, and Abraham

The people of Israel were also unique in ancient Near Eastern religion in their belief that God had established a Covenant relationship with them and with their ancestors. In the Catholic Bible Dictionary (Doubleday 2009) a companion volume to the Ignatius Catholic Study Bible, Dr. Scott Hahn identifies a sequence of Covenants found in the biblical text. There are six of them, each built upon the preceding one. Together they account for all of Salvation History. They are identified through the mediation of different individuals: Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, and then ultimately, in the Covenant that fulfills them all, Jesus Christ.

In the Creation Covenant mediated by Adam, creation culminates on the Sabath, which is the sign of a Covenant elsewhere in Scripture (Exodus 31:12-17). The term used for the making of the Covenant with Noah is not the usual one for Covenant initiation (in Hebrew, kārat), but rather a term indicating the renewal of a pre-existing Covenant (in Hebrew, hēqim).

The five Covenants before Jesus end in varying degrees of failure or success. The Covenant with Adam collapses upon the revelation of his disobedience. Having eaten from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in disobedience to the directive of God, the Covenant collapses as Adam is cast out from Eden. Many generations later God establishes a new Covenant with Noah. In an act of both judgement and re-creation God again plunges the world under the primordial waters described in Genesis 1:2. God saves the righteous man, Noah and his family along with pairs of every animal and creature in an ark. As the water receded, the ark came to rest on Mount Ararat. Noah, a new Adam figure, emerges from the ark and performs the priestly act of offering sacrifice (Genesis 8:20). God renews the previous Covenant repeating the blessings originally given to Adam. According to John S. Bergsma, PhD, in his “Overview of Salvation History,” “sin has left a lasting wound,” and disharmony between man and nature. But the filial relationship of man in Covenant with God does not last long. Noah betrays his priestly-patriarcal role. He becomes drunk and lies naked in his tent (Genesis 9:21). His son Ham, in an enigmatic deed described in Genesis as seeing “the nakedness of his father” (Genesis 9:22) causes Noah to curse Ham’s descendents through his son Canaan (Genesis 9:25). The phrase, “seeing the nakedness of his father,” is widely seen as a euphemism for an incestuous encounter between Noah’s son Ham and the wife of Noah. So where the Covenant with Adam was marred by disobedience, the Covenant with Noah was marred by perversion.

Many generations pass through the next three chapters of Genesis when, in Genesis 12:3, God bestows upon Abram the promises of a great nation, a great name, and universal blessing upon mankind. God incorporated these promises into a formal Covenant. Then God bestowed upon Abram a greater name, “Abraham” (Genesis 17:5). This Covenant becomes subjected to the ultimate test of loyalty: that Abraham should offer his beloved son Isaac in sacrifice to God (Genesis 22:2). I explored this account in detail in “Behold the Lamb of God Upon the Altar of Mount Moriah.”

An Angel of the Lord stayed Abraham’s hand and pointed to a ram in the thicket, which became the substitute sacrifice for Isaac just as 2,000 years later, Jesus became the substitute sacrifice for us.

The Covenants of Moses, David, and Jesus

Unlike the aftermath of the Covenants with Adam and Noah, the Covenant with Abraham did not collapse under a catastrophic fall. Even though the Covenant is complicated by the sins of his descendants, God fulfills his promise to Abraham, but Abraham’s lineage ends up in Egypt.

Generations passed. Abraham’s descendant, Joseph, one of the sons of the Patriarch Jacob, was betrayed by his own brothers and sold into slavery in Egypt. Thus, centuries later, Israel became a nation in bondage in Egypt until Moses led the Israelites out of captivity to the Promised Land. God called upon Moses from a burning bush on Mount Horeb (Exodus 3:6, 10). God identified himself as “The God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob. Come, I will send you to Pharaoh that you may bring forth my people, the sons of Israel, out of Egypt.”

Once the children of Israel were released from bondage, Moses led them to Mount Sinai where the Lord established a national Covenant — the Decalogue, the Ten Commandments. No sooner than the Sinai Covenant had been established, however, it was broken. Some Israelites were enticed at Mount Sinai into worship of a golden calf, an icon of an Egyptian deity. Moses expelled them and then Israel was subjected to wandering in the desert as penance. Moses is mentioned more in the New Covenant (the New Testament) than any other Old Testament figure.

Centuries later, around 1,000 BC, King David arose in Salvation History. He descended from the tribe of Judah and is introduced in Scripture as a young shepherd in Bethlehem, which came to be known in our Nativity accounts as the “City of David.” David was a gifted poet and musician. He composed many of the psalms in the Hebrew Bible setting some of them to music. He was also a warrior known to history as having slain the giant Philistine warrior, Goliath (1 Samuel 17:48).

The Prophet Samuel annointed David as King over Israel, “and the Spirit of the Lord came mightly upon David from that day forward (1 Samuel 16:13).” Like a New Adam, David also functioned as a priest and a prophet while Israel expanded to become an empire.

Under the reign of David’s son, Solomon, Israel became a great military power in the Ancient World. His greatest accomplishment was the building of the Temple in Jerusalem and the Ark of the Covenant, which I described in these pages in “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The terms of Davidic Covenant are layed out in 2 Samuel 7. The elements of the Davidic Covenant include Nathan’s oracle (2 Samuel 7:8-16) about David’s intention to build a sanctuary for Yahweh.

The New Covenant Gospels, especially Matthew and Luke, depict Jesus as the heir of David and the one to restore the Davidic Covenant. God’s Covenant with Jesus was the Institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. Jesus identifies his own body and blood as the sacrificial elements of this New Covenant.

This was something entirely new in the Bible and in Salvation History. Jesus did not simply make a Covenant, but rather “became” a Covenant, a living bridge linking us to God. It was, and is, the fulfillment of all of Salvation History.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. It will be added to our collection of special Scripture posts about Salvation History.

You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

A Vision on Mount Tabor: The Transfiguration of Christ

Behold the Lamb of God Upon the Altar of Mount Moriah

The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God

On the Great Biblical Adventure, the Truth Will Make You Free

+ + +

“This is my beloved Son on whom my favor rests.”

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Fr Charles Engelhardt’s Indicted Prosecutor Took a Plea Deal

With strange testimonial ties to the Cardinal George Pell case in Australia a corrupt U.S. prosecutor faced a 23-count indictment of his own and took a plea deal.

With strange testimonial ties to the Cardinal George Pell case in Australia a corrupt U.S. prosecutor faced a 23-count indictment of his own and took a plea deal.

January 21, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

On January 7, 2026 in these pages I exposed a story with new and relevant information about the notorious case of Cardinal George Pell of Australia who became the first Roman Catholic cardinal to be accused, tried and convicted on sexual abuse charges. It was a media event with global coverage that survived two appeals affirming the conviction and sentence until Australia’s highest court reversed the conviction in April, 2020. It was a story I covered here in “From Down Under, the Exoneration of George Cardinal Pell”

When I wrote of his exoneration in 2020, I was not aware of the tentacles of connection between the testimony against Cardinal Pell on trial in Australia, and that of another Catholic priest almost simultaneously on trial in America. As one prominent Australian writer exposed, “These similarities are too many to be attributed to chance.”

In an epilogue at the end of my January 7, 2026 post, I included this paragraph:

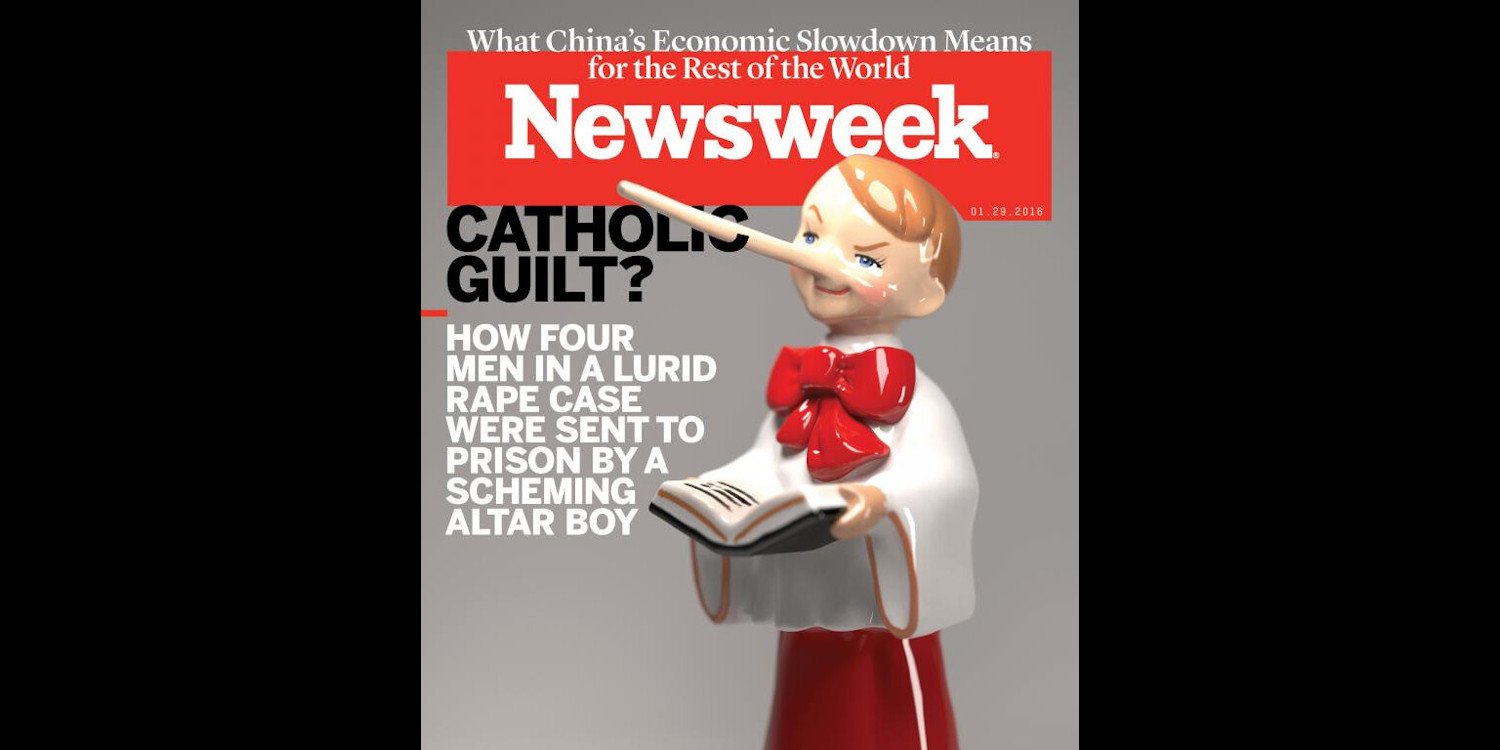

“There is a background story about the origin of the false charges against Cardinal Pell. It came out of the United States when a young con man named Daniel Gallagher was allowed to use a pseudonym, Billy Doe, to bring phony charges against several Catholic priests in Philadelphia, one of whom died in prison. The story was propelled forward by Sabrina Rubin Erdely and Rolling Stone magazine. It has been exposed as fraudulent, including here at Beyond These Stone Walls in “The Lying, Scheming Altar Boy on the Cover of Newsweek.”

It is important to restore integrity to the justice system in this regard because it was exploited by corrupt individuals on two continents to attack the Catholic Church through the enticement of the almighty dollar. The stage was set for this story by some other con artists posing as “victim advocates.”

Some of the mighty have fallen from their public ruse as self-proclaimed champions of truth, justice, and the American way. The entire landscape of the Catholic Church in America was altered by the work of David Clohessy, Barbara Blaine, and “SNAP,” the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests.” If you click on that link (which is linked again at the end of this post) you will get an eyeful about the financial corruption that has been the jaded hallmark of many of the modern-day claims of sexual abuse by Catholic priests.

There are some in Australia and beyond who have taken a position that a postmortem on the Pell case is unwarranted because he is deceased while other matters of justice and injustice are still alive. That reflects a most jaded sense of justice because if we cannot learn from our mistakes then we are doomed to repeat them. And we have repeated them.

SNAP also made the American Catholic bishops shudder, spawning policies that, in the quest to assuage SNAP and satisfy lawyers, brought great harm to the priesthood and the relationship between bishops and priests. The damage was summed up in a single sentence by Canadian Catholic blogger, Michael Brandon, in an assessment of Beyond These Stone Walls:

“The Catholic Church has become the safest place in the world for young people and the most dangerous place in the world for Catholic priests.”

Now, ever so slowly, much of the media and prosecutorial spin woven by SNAP has unraveled. While most Catholic leaders were cowered into accommodating silence, the Catholic League for Religious & Civil Rights led by Bill Donohue, published “SNAP Implodes” (Catalyst, March, 2017). It is a must read, an essential and accurate expose of a corrupt organization designed solely out of hatred and animus for the Catholic Church.

It is a stunning summation of SNAP’s seismic fall. A lawsuit against SNAP by one of its top officials unmasked all that Bill Donohue suspected to be true. SNAP officials stood accused of fraud and a financial kickback scheme with personal injury lawyers. SNAP is alleged to have used the plight of victims — real and fraudulent — to pad its own bottom line. I also wrote of this recently in “To Fleece the Flock: Meet the Trauma-Informed Consultants.”

A Thin Line Between Prosecution and Persecution

Among the most widely read and shared posts at this blog was one I wrote in January, 2016, entitled, “The Lying, Scheming Altar Boy on the Cover of Newsweek.” Readers found it to be shocking and compelling. What I found most shocking was how the lurid testimony of Daniel Gallagher was somehow repackaged and recycled for the trial of another priest on another continent, Cardinal George Pell in Australia. The Newsweek account by journalist Ralph Cipriano profiled the story of Father Charles Engelhardt, a Catholic priest who died chained to a gurney in the hospital wing of a Pennsylvania prison because he refused a lenient plea deal while maintaining his innocence. This aspect of this story should sound eerily familiar to our readers.

As the story that landed Father Engelhardt in prison was sensationalized in the press, facts became lost in the national coverage. Rolling Stone magazine’s now-infamous former crime reporter, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, hyped the story of lascivious Philadelphia priests molesting innocent youths while bishops looked the other way. That was two years before Ms. Erdely was deposed for vastly irresponsible journalistic practices. After her lurid account of “Billy Doe” molested by Father Engelhardt and then “traded” to other priests, Ms. Erdely went on to be conned by another fraudulent claim brought by “Jackie.” This time the accused were fraternity students at the University of Virginia, and they too turned out to be innocent.

Unlike the Catholic targets of Rolling Stone, UVA and the students sued for defamation. The result was a multi-million dollar judgment against Rolling Stone and Sabrina Rubin Erdely for her “Rape on Campus” story, described by jurors as “reckless disregard for truth.” Ms. Erdely was quickly and quietly dropped from the Rolling Stone editorial staff. I wrote more of this story in “The Path of Sabrina Rubin Erdely’s Rolling Stone.”