The First of the Four Last Things: An Advent Tale

In ages past, Advent prepared for the First Coming of Christ by the “momentum mortis,” the first of the Four Last Things. It’s an urgent matter behind These Stone Walls.In the second decade of the Nineteenth Century, the American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson was a student at Harvard Divinity School where, 150 years later, my Jesuit uncle became its first Roman Catholic dean. That fact alone would have seriously rankled Harvard’s Puritan founders who established the college in 1636, sixteen years after the Mayflower pilgrims landed at Plymouth. One of the first official acts of the Puritans’ Massachusetts Bay Colony was to outlaw any observance of Christmas.Nearly two centuries later, at Christmas, 1827, Emerson traveled by horse and buggy from Cambridge to visit the Concord, New Hampshire State Prison. He was horrified to learn that the prison was inhumanely overcrowded with a total of 82 prisoners confined in cells designed to hold 36. Emerson wrote of the experience:

In ages past, Advent prepared for the First Coming of Christ by the “momentum mortis,” the first of the Four Last Things. It’s an urgent matter behind These Stone Walls.In the second decade of the Nineteenth Century, the American poet Ralph Waldo Emerson was a student at Harvard Divinity School where, 150 years later, my Jesuit uncle became its first Roman Catholic dean. That fact alone would have seriously rankled Harvard’s Puritan founders who established the college in 1636, sixteen years after the Mayflower pilgrims landed at Plymouth. One of the first official acts of the Puritans’ Massachusetts Bay Colony was to outlaw any observance of Christmas.Nearly two centuries later, at Christmas, 1827, Emerson traveled by horse and buggy from Cambridge to visit the Concord, New Hampshire State Prison. He was horrified to learn that the prison was inhumanely overcrowded with a total of 82 prisoners confined in cells designed to hold 36. Emerson wrote of the experience:

“At this season, they shut up the convicts in these little granite chambers at about 4 o’clock PM and let them out about 7 o’clock AM - 15 dreadful hours.”

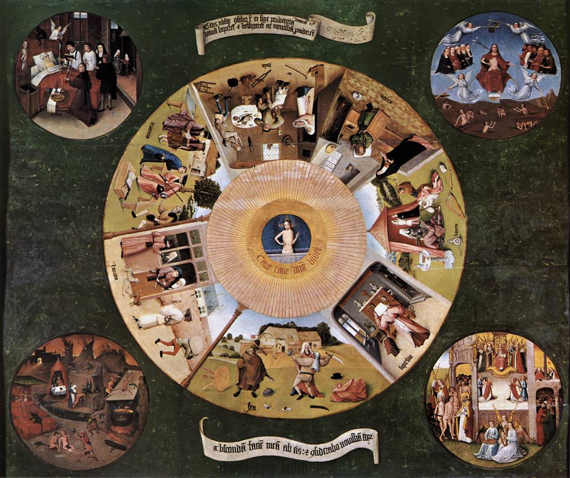

The challenges of Christmas in prison have only magnified since Emerson wrote of it. Today, the Concord, NH prison has swelled to nearly 3,000 prisoners still confined in cells designed for less than half that number. Confinement for the holidays hasn’t changed much either. When I first titled this post, I settled on “Christmas on the Bipolar Express,” but the tides of life in captivity made me reconsider.In Emerson’s day it would have been unheard of, for prison sentences were a fraction of what they are today, but I am approaching my 21st Christmas in prison, and it’s the 23rd for our friend Pornchai-Maximilian who went to prison at age 18. When we tell this to younger prisoners on the verge of their annual Christmas trip aboard the bipolar express they stare at us in shock and awe. “That’s so depressing,” they say.It’s an odd thing that prisoners here seem to calculate time in prison using Christmas as a benchmark. When I ask other prisoners how long they have been here, they usually have to think about it. But when I ask them how many times they have been in prison for Christmas, the answer is instant and accurate, and usually followed by a look of profound sadness.When I wrote “The Missiles of October,” I ended with a statement that the missiles aimed at us in prison are many and great, but I cannot focus on them. There are just too many amazing things happening behind these stone walls for me to bemoan all the target practice. I wrote that I’m looking forward to telling you about some of the better news.And I already have. One of those amazing things is the Tapestry of God I described in “A Stitch in Time” recently. What has unfolded in the life of Pornchai Moontri since his Divine Mercy conversion is wonderful and mysterious to behold. The fact that we behold it at Christmas in one of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “little granite chambers,” confined for two decades and counting, is actually a part of that miracle. We were powerless to bring about the wonderful developments, connections and reunions that Pornchai-Maximilian now celebrates - the ones that are saving his life after Divine Mercy saved his soul.THE FOUR LAST THINGS The sheer grace of that story dwarfs prison. For me, it nearly silences all its gloom and doom - even at Christmas. But there are many other stories running parallel to ours, and one of them has been unfolding with new developments that are simply amazing. It’s the story of Anthony Begin that I first told in “Pentecost, Priesthood, and Death in the Afternoon.”In modern times, the Advent season has become almost entirely an anticipation of Christmas and its good tidings of comfort and joy, but Advent wasn’t always so upbeat. It used to be a time to reflect on a reality most of us in Western Culture now take great pains to avoid: the “momentum mortis,” the anticipation of our own death, the first of the Four Last Things which consider our final destiny.Since ancient times in the consciousness of the Church, Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell have been acknowledged as the inevitable destinies of humankind, the Four Last Things, and Advent was a time to come to terms with them. As the First Letter of Saint Peter warns:

The sheer grace of that story dwarfs prison. For me, it nearly silences all its gloom and doom - even at Christmas. But there are many other stories running parallel to ours, and one of them has been unfolding with new developments that are simply amazing. It’s the story of Anthony Begin that I first told in “Pentecost, Priesthood, and Death in the Afternoon.”In modern times, the Advent season has become almost entirely an anticipation of Christmas and its good tidings of comfort and joy, but Advent wasn’t always so upbeat. It used to be a time to reflect on a reality most of us in Western Culture now take great pains to avoid: the “momentum mortis,” the anticipation of our own death, the first of the Four Last Things which consider our final destiny.Since ancient times in the consciousness of the Church, Death, Judgment, Heaven, and Hell have been acknowledged as the inevitable destinies of humankind, the Four Last Things, and Advent was a time to come to terms with them. As the First Letter of Saint Peter warns:

“Be sober and alert. Your opponent the devil is prowling about like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour. Resist him, firm in your faith, knowing that the same experience of suffering is required of your brotherhood throughout the world.” (1 Peter 5:8-9)

It’s a challenge in our era to reconcile Saint Peter’s admonition when, for many, Christmas has been diminished into a secular, materialistic “holiday season.” But the gravity of the First Coming of Christ requires that we overcome that challenge.I laid out the connection between the Fall of Man and the Birth of Christ in another Advent post, “I’ve Seen the Fall of Man.” Since then, Anthony Begin has renewed his interest in the Four Last Things, and most certainly my own as well.“AM I LIVING OR AM I DYING?”Six months ago, at the age of 49, Anthony discovered that he has terminal stage four cancer. After years of complaining of pain in his chest, an x-ray revealed a large mass on one lung. Then an MRI revealed that the malignant cancer had spread to his spine, lymph nodes, and brain. He was told that aggressive radiation treatments and chemotherapy. might give him months to live. Within weeks of this discovery last May, Anthony’s condition deteriorated quickly, and he was consigned to the prison hospital, a prison within the prison, where he was to die.In the months to follow, I was able to see Anthony only from a distance as he waved from a far window while we passed on the long walk across the walled prison yard to the dining hail. His attempts to have me and Pornchai visit him were denied. But on some Sunday mornings, Anthony was allowed the rare privilege of leaving the hospital for an hour to climb a few flights of stairs to the prison chapel for Sunday Mass.Largely because of his interaction with Pornchai Moontri, Anthony decided to become Catholic and was received into the Church near the end of July. Like Pornchai, Anthony finds much grace through the Divine Mercy apostolate.By October, Anthony’s prognosis got worse - much worse. Even as chemotherapy commenced, the cancer advanced. New scans revealed new tumors in the brain. An oncologist told Anthony that he may have a few months to live. In the brief few minutes he had to discuss this with us before and after Mass, I noted the struggle between Anthony’s fear and the trust he was finding in his newly discovered faith. After one Mass, I gave Anthony a copy of a TSW post, “The Holy Longing,” an All Souls Day post about the hopefulness of purgatory.Then, suddenly, on the Solemnity of Christ the King, the one year anniversary of our Consecration following the “33 Days to Morning Glory” retreat, Anthony told Pornchai and me something astonishing. A new scan that week showed that the tumors on Anthony’s lymph nodes were no longer visible, and all the others had shrunk by half. “It’s not remission,” the startled oncologist told him. “Your cancer seems to have gone to sleep.”The next day, the prisoner in the overflow bunk just outside our cell door was suddenly moved somewhere else. We were told only that the bunk is being held for someone. The day after that, Anthony showed up, released - for now - from the prison hospital. “Go live your life,” the prison doctor told him.Anthony will be taken for a new P.E.T. scan in three months, but, for now, we are looking out for him. His few remaining months have now become “maybe two years.” Anthony lost a lot of weight, and all his hair, and his health is seriously depleted, but he is overjoyed to be back.Anthony and Pornchai and I have been discussing the Four Last Things in preparation for the First Coming of Christ at Christmas. “I don’t know whether I’m living or dying now,” Anthony said. He’s doing both. We’re all doing both.I just showed them a paragraph about an intriguing new book, True Paradox (InterVarsity Press 2014) by David Skeel, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania. The book was reviewed by Barton Swain in a recent issue of The Wall Street Journal (“In Praise of Gentle Apologias,” Nov. 22/23, 2014). Barton Swaim described the book:

“To make the point vivid, Mr. Skeel describes the final illnesses of two very different men: The contrarian journalist Christopher Hitchens and Harvard Law professor William Stuntz. Hitchens was an atheist, Stuntz a committed Christian.”

True Paradox charts the great difference between the ways these two men thought about, and wrote about, their terminal cancer. The most captivating chapter deals with the afterlife. Barton Swaim described David Skeel’s argument:

“No one who achieves great things ... really believes those achievements are pointless, destined to fade into nothingness ... our work on earth will somehow find its fulfillment in heaven... The Bible strongly implies that the Christian’s life in eternity will extend his earthly life’s complexity, only without failure and rebellion against God.”

Anthony found this to be profoundly hopeful. So do I. It’s also sobering, calling to mind that our “momentum mortis” is something far deeper than a reflection on death. It’s a reflection also on the art of living, and it’s the greatest of Advent hopes. Opening ourselves to the Birth of Christ lets fall away all the hubris of being human. We belong to Christ, and we have but a little Advent left to come to terms with that.Anthony, too, has seen the Fall of Man. He has seen it in himself and all around him. The great thing he is now to achieve, the thing he will take into life in eternity, is the sure knowledge that no one can witness the Birth of Christ, and remain a prisoner.