In the Year of the Priest, the Tale of a Prisoner

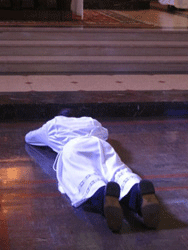

This Saturday, June 5th, is my 28th anniversary of ordination to the priesthood. I remember every detail of that day as though it was yesterday. I was the only priest ordained for the Diocese of Manchester in 1982. As I wrote in my Lenten post, "Going My Way,""I remember vividly what was going through my mind as I lay face down on the floor before the altar that day while the choir chanted the Litany of the Saints. I was conscious of two things In particular: of how very much I am unlike those saints we were invoking in that very moment, and of how very great were their own trials and sufferings in the crosses they bore."I wondered on the day I was ordained if all my days as a priest would be as special as that day. As I lay prostrate on that floor before the altar in a gesture of humility before God I was also conscious of the fact that my mother and father, my sister and brothers knelt just a few feet away.My family never accepted my vocation to priesthood, and they had some dismal forebodings about what was in store for me. My father died suddenly at the age of 52 just months after I was ordained. Someday soon, I plan to write about him.I wrote a post about my mother last December, and described how my life as a priest, and then as a prisoner, affected her. If there is a single post I would want TSW readers to read anew, it's that one, "A Corner of the Veil." I consider it to be the most important post I have written, not because it was about my mother, but because it was about the subtle signs of grace in our lives, and how we can miss them if we're not inclined to see them.That, to me, is exactly what faith is. It's being inclined to see signs of God's Presence in hard times. "A Corner of the Veil" is not just about death and loss it’s about something hinted at In the Letter to the Hebrews:

This Saturday, June 5th, is my 28th anniversary of ordination to the priesthood. I remember every detail of that day as though it was yesterday. I was the only priest ordained for the Diocese of Manchester in 1982. As I wrote in my Lenten post, "Going My Way,""I remember vividly what was going through my mind as I lay face down on the floor before the altar that day while the choir chanted the Litany of the Saints. I was conscious of two things In particular: of how very much I am unlike those saints we were invoking in that very moment, and of how very great were their own trials and sufferings in the crosses they bore."I wondered on the day I was ordained if all my days as a priest would be as special as that day. As I lay prostrate on that floor before the altar in a gesture of humility before God I was also conscious of the fact that my mother and father, my sister and brothers knelt just a few feet away.My family never accepted my vocation to priesthood, and they had some dismal forebodings about what was in store for me. My father died suddenly at the age of 52 just months after I was ordained. Someday soon, I plan to write about him.I wrote a post about my mother last December, and described how my life as a priest, and then as a prisoner, affected her. If there is a single post I would want TSW readers to read anew, it's that one, "A Corner of the Veil." I consider it to be the most important post I have written, not because it was about my mother, but because it was about the subtle signs of grace in our lives, and how we can miss them if we're not inclined to see them.That, to me, is exactly what faith is. It's being inclined to see signs of God's Presence in hard times. "A Corner of the Veil" is not just about death and loss it’s about something hinted at In the Letter to the Hebrews:

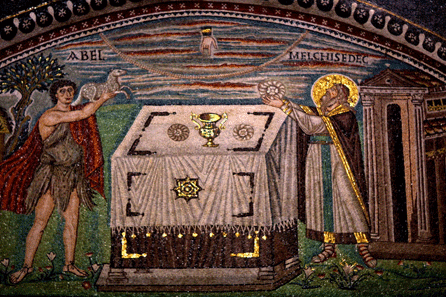

"Since we have confidence to enter the sanctuary by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way he opened for us through the veil, that is, through his flesh, and since we have a great priest over the house of God, let us approach with sincere hearts and absolute trust."

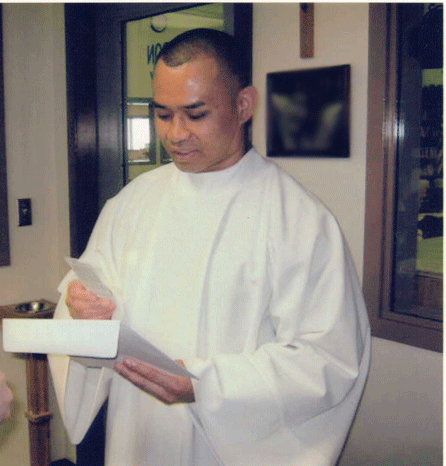

Absolute trust is easier said than done. A lack of trust is the biggest obstacle to grace I've encountered in myself and others. When Pornchai Moontri received his First Eucharist on Divine Mercy Sunday (see "In Honor of Saint Maximilian Kolbe") Bishop John McCormack pointed out in his homily that he read "Pornchai's Story." He said that Pornchai's conversion was the result of one key factor: despite all evidence in his life pulling him to do the opposite, Pornchai opened himself to risk trusting someone.

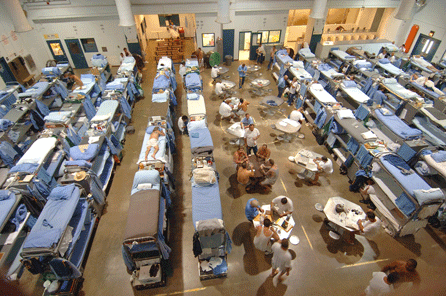

The power of trust should not be underestimated, but trust in the Church and priesthood have been seriously eroded. Trust in priests has been all but destroyed in the public square, and priests have seen their trust for their bishops and Church evaporate even as the Year of the Priest commenced. I plan to write more about this in two weeks as the Year of the Priest comes to an official close.What in this world can any of us trust in? I think the erosion of faith in our culture is really an erosion of trust. It is crucial to faith that we learn to recognize grace in hard times, and to trust in that. For some of us, hard times are already upon us. For all of us, sooner or later, they are coming. I find it easy to trust when all is well, but in the middle of a perfect storm, my ability to trust is always what sinks first, and once destroyed it is very difficult to restore.EXCAVATING THE RUINS OF A LIFESome things have happened recently that have caused me to focus my thoughts away from the dismal news media coverage of the priesthood that has us all squirming in our seats. When my mother died while I was in prison, she left a painful void. She was my link to my family, and without her that link has slowly and painfully diminished. It happens to everyone in prison. I described the "ten-year syndrome" in my Advent post, "Angels We Have Heard on High." Time in prison stretches families to their limits. Weekly visits turn into monthly visits, then yearly, then years pass.I felt the distance most acutely a few weeks ago. Charlene came across the Facebook pages of my brother and one of my nieces. My niece was eight when I came to prison. Now she's 24. I found it heartbreaking to realize I know little to nothing of the people and events described on the Facebook pages, and I am entirely absent from their lives. The chasm of alienation felt wide indeed.The separation from others that I feel so acutely as a priest in prison is itself a source of grace, though perhaps not for me. Wounds of alienation help me see it most clearly - and also most painfully - in others. I live every moment of every day with other prisoners who have burned bridges with their fractured lives. All but the most fortunate of prisoners eventually lose contact with the lives they had outside. Time in prison causes what they had to slip quietly, inexorably away. Some others never had bridges to begin with. For some, repairing the damage of a shattered life seems impossible.As I'm typing this post, Skooter - he insists it's spelled with a “k" - is sitting a few feet away on Pornchai's concrete stump staring at my small television. Skooter doesn't have a TV, or anything else for that matter, so sometimes I turn mine toward the door so he can see it.I have known Skooter for about a year and a half. He is twenty-four years old, the same age as my niece, but it's startling how different their worlds and life experiences are. My niece - thank the Lord - has never had to define herself apart from her family and upbringing. Skooter's life, in contrast, rests on the edge of a knife.He got into trouble in the last unit where he lived, and as a result was moved to the place where Pornchai and I live. He is one of the people who lives in the overflow space in a bunk in the recreation area just outside our door. As I described in the second half of last week's post, there are more prisoners in this prison than cells to put them in.

Skooter belongs nowhere. A few days ago, he came in and sat down. He asked me what I was typing, and I told him I was writing about the death of my mother while I was in prison, and of how painful it was not to be able to see her or comfort her as she was dying. Skooter was silent with that sort of heavy silence that happens when you say something someone else finds troubling. I knew my response sent Skooter into some distant corner of his mind, and I could feel the pain he was in. I asked him about his family, but he said nothing.I have never seen Skooter receive mail or be called for a visit. He wears a pair of sneakers with a hole in the sole the size of Australia. It almost seems symbolic of the gaping hole in his own soul. It's more like an abyss, and I knew that extracting the details was going to be difficult, but inevitable.Sooner or later, if their stay in prison is long enough, most prisoners are cut off and cast adrift by society. There are some who are even cast aside by other prisoners. Skooter is one of them. Pornchai told me that some other prisoners suggested that we should not talk to Skooter or help him. When Pornchai asked why, they had no answer.

Skooter belongs nowhere. A few days ago, he came in and sat down. He asked me what I was typing, and I told him I was writing about the death of my mother while I was in prison, and of how painful it was not to be able to see her or comfort her as she was dying. Skooter was silent with that sort of heavy silence that happens when you say something someone else finds troubling. I knew my response sent Skooter into some distant corner of his mind, and I could feel the pain he was in. I asked him about his family, but he said nothing.I have never seen Skooter receive mail or be called for a visit. He wears a pair of sneakers with a hole in the sole the size of Australia. It almost seems symbolic of the gaping hole in his own soul. It's more like an abyss, and I knew that extracting the details was going to be difficult, but inevitable.Sooner or later, if their stay in prison is long enough, most prisoners are cut off and cast adrift by society. There are some who are even cast aside by other prisoners. Skooter is one of them. Pornchai told me that some other prisoners suggested that we should not talk to Skooter or help him. When Pornchai asked why, they had no answer.

To Pornchai's credit, he did just the opposite of what other prisoners advised. Skooter told me a few days ago that visiting us is the only place he can go "where I don't feel like a stray dog in a cage."

Skooter is one of the most broken and wounded persons I know. Verbal communication is not his strong point, but in the time I have known him I have slowly learned some things about him. Most of it came out all at once, and it was awful for Skooter, but it may be a turning point in his life. I asked him yesterday if I could write about what he told me. I won't use his real name. I told Skooter I would be careful not to divulge too many details, but he asked me to write everything.FROM OUT OF THE DEPTHSIt's hard to describe the brokenness of the person sitting a few feet away staring intently, lost in a mindless TV show. Most of you do not have a category in which to understand the aftermath of such a shattered life. Skooter, his head shaved, his right arm covered in prison tattoos, looks as menacing as a wounded person possibly can. Skooter said I am the first person he has ever told of his past. I believe him. He wasn't able to tell most of it even to me. Instead, he spent all night writing, and gave his story to me in the morning. He titled it, "The Life of Skooter." It's not an easy story to tell.When Skooter was seven years old, he lived with his mother in a shabby two room apartment in Los Angeles. She lived with a heroin addiction, and Skooter lived with all that that entails. Those details are just too gruesome to repeat. Skooter's mother was then at the lowest point in her life, and he was orphaned by heroin. The electricity had been shut off for lack of paying the bill.One night, Skooter's mother, who never came out of her room, was trying to inject heroin by the light of the same candle she cooked it with. She could not manage the strap so she began to scream for Skooter to help her. He didn't want to, but she screamed in agony. Skooter's last memory of his mother was injecting her heroin for her at the age o f seven. "I can hear her right now, screaming at me to do it," Skooter said. He tied the strap on her arm, and had to inject the drug into her vein because she was shaking too much. She overdosed and stopped breathing.Skooter's mother survived somehow, but just barely. She disappeared for days, then was arrested selling drugs to an undercover federal agent. She went to prison. It would be many years before Skooter would see his mother again.Skooter's sole ally and support through all this was Corey, his half brother. Corey. ten years older than Skooter, had the same mother but different fathers. Skooter idolized Corey who became his lifeline, plucking Skooter from the chasm of state foster care and group homes. It was Corey who gave Skooter his name – “k .”At about the same time I was sent to prison in 1994, Skooter was eight years old and throwing a ball with Corey on a Los Angeles street. Corey's gang became his family, and, by extension, Skooter's as well. While they threw a ball back and forth in the street, Skooter held the ball to let a car pass. The car quietly slowed down in front of them, the passenger side window came down, and Corey was gunned down in the street while Skooter watched helplessly. Skooter told me that both their lives ended that day.It was the last time Skooter felt anything at all. He collapsed in the street shaking uncontrollably. For the next five years, Skooter was moved between state schools and foster homes. He ceased to trust anyone, and the downward spiral of his life kept plunging. At thirteen, Skooter was sent to a juvenile jail. His anger became simply alarming, and he stopped caring about himself or anyone else.As I write this, the local news in New Hampshire is airing the story of a 53-year-old man who just remembered being "fondled" by a long-deceased priest in 1963, the year John F. Kennedy died, and the man is pathetically describing for the camera his long-suffered post traumatic stress disorder. When the news clip finished, Skooter looked up at me.

f seven. "I can hear her right now, screaming at me to do it," Skooter said. He tied the strap on her arm, and had to inject the drug into her vein because she was shaking too much. She overdosed and stopped breathing.Skooter's mother survived somehow, but just barely. She disappeared for days, then was arrested selling drugs to an undercover federal agent. She went to prison. It would be many years before Skooter would see his mother again.Skooter's sole ally and support through all this was Corey, his half brother. Corey. ten years older than Skooter, had the same mother but different fathers. Skooter idolized Corey who became his lifeline, plucking Skooter from the chasm of state foster care and group homes. It was Corey who gave Skooter his name – “k .”At about the same time I was sent to prison in 1994, Skooter was eight years old and throwing a ball with Corey on a Los Angeles street. Corey's gang became his family, and, by extension, Skooter's as well. While they threw a ball back and forth in the street, Skooter held the ball to let a car pass. The car quietly slowed down in front of them, the passenger side window came down, and Corey was gunned down in the street while Skooter watched helplessly. Skooter told me that both their lives ended that day.It was the last time Skooter felt anything at all. He collapsed in the street shaking uncontrollably. For the next five years, Skooter was moved between state schools and foster homes. He ceased to trust anyone, and the downward spiral of his life kept plunging. At thirteen, Skooter was sent to a juvenile jail. His anger became simply alarming, and he stopped caring about himself or anyone else.As I write this, the local news in New Hampshire is airing the story of a 53-year-old man who just remembered being "fondled" by a long-deceased priest in 1963, the year John F. Kennedy died, and the man is pathetically describing for the camera his long-suffered post traumatic stress disorder. When the news clip finished, Skooter looked up at me.

How do I explain to Skooter why that man's PTSD is now worth a six-figure settlement while Skooter can't afford a 20-cent package of Ramen noodles? Anyone? ••• Anyone?

There is no force on Earth that can repair the damage done to Skooter's life. Only Christ can restore his soul, and I have to believe with the absolute trust necessary for priesthood that, despite all appearances, there is hope for Skooter.At twenty-four, half of his life has been spent in prisons of one sort or another. Skooter has not fared well in prison. He has been in many fights, and even the most rudimentary forms of trust elude him. He knows this. Trust is by far the most damaged part of who Skooter is. How does this man learn to ever trust anyone? Skooter told Pornchai that he trusts me. How is that even possible?HEAVILY BURDENEDThere is a Catholic Mass in the prison three times a month, and Pornchai and I usually participate even though I still celebrate Mass late at night on Sundays (see 'Sacrifice of the Mass"). Last week, Skooter asked me if he could attend with us. Of course I said yes, but I wasn't anticipating he would actually go.On Sunday morning Skooter was ready. To get to the prison Chapel, we have to walk through multiple locked doors, get outside, walk through a number of security gates, then walk across the long, walled prison yard to the Administration building, then up six flights of metal grate stairs, through two more locked doors, present a pass, sign in, then go into the Chapel. It can be quite an ordeal.Skooter was lagging behind. The closer Pornchai and I got to the prison Chapel, the further behind Skooter drifted. When I got to the top of the stairs, I looked out across the prison yard to see Skooter, head down, turn on his heels and walk back to whence he came. I understand what happened. When he is ready, we’ll try again.Skooter is deeply angry with God, and it is that which turned him back. Hope is simply not something a man can pretend to have. Skooter cannot harbor intense anger and the beginnings of hope at the very same time. One or the other has to go. When he tried to explain his about face, I stopped him. I told him we will save him a seat with us until he is ready to take his place in it.I have been pretty resentful of late about the course of my life as a man and as a priest. I resent losing my freedom for something that never even happened. I DEEPLY resent losing the trust of others, and, for my trouble, gaining the scorn of many for a crime that never took place. I just cannot put into words how much I resent this, and how much that resentment now inhibits my faith and my hope and my life as a priest. I miss the days when I could just comfortably save the saved, and didn’t have to worry about any soul beyond my own.I missed those days until I heard Skooter and Pornchai laughing this morning, and saw a light in Skooter’s eyes that wasn’t there yesterday.There is hope for Skooter. There is hope for us all.

![]()