"Phasers on Stun, Mr. Spock!" Captain Kirk's Star Trek Epiphany

In the 1960s, when religion became a quaint anachronism on American TV, Star Trek's Captain James T. Kirk declared the Birth of Christ a cosmic event.Last June, I began my post, "A Day Without Yesterday" with a disclaimer. I felt it necessary to warn TSW readers that my story about how Father Georges LeMaitre changed the mind of Albert Einstein on the created Universe could not be told without a hefty dose of science. I love science, and Father LeMaitre is one of my personal heroes of both science and faith. I was really happy that at least some TSW readers actually liked that post. But I was ecstatic when it ended up on the Facebook page of "The Catholic Laboratory." Maybe my science disclaimer wasn't needed after all.I blame the disclaimer on my sister, Debbie. She had a birthday on December 4, so I'd appreciate a prayer for her. I'm almost two years older than Debbie so I've known her for all 56 of her 39 years. She's my favorite sister. Well, yeah, she's also my ONLY sister, and, though I didn't always show it, I had much sympathy for her having to grow up with three brothers.Debbie doesn't know it, but she actually makes a sound when she rolls her eyes. It's kind of a nasally sniff that always accompanies the eye-roll, and I can hear it when we speak by telephone. I learned at age 13 that any mention of science or science fiction, and especially any mention of Star Trek, will set Debbie's famous eye-roll into motion. It works to this very day. When I told her a few months ago about "A Day Without Yesterday," I could hear her eyes roll across the miles of interstate telephone lines between us.

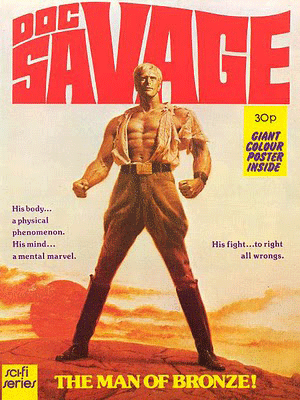

In the 1960s, when religion became a quaint anachronism on American TV, Star Trek's Captain James T. Kirk declared the Birth of Christ a cosmic event.Last June, I began my post, "A Day Without Yesterday" with a disclaimer. I felt it necessary to warn TSW readers that my story about how Father Georges LeMaitre changed the mind of Albert Einstein on the created Universe could not be told without a hefty dose of science. I love science, and Father LeMaitre is one of my personal heroes of both science and faith. I was really happy that at least some TSW readers actually liked that post. But I was ecstatic when it ended up on the Facebook page of "The Catholic Laboratory." Maybe my science disclaimer wasn't needed after all.I blame the disclaimer on my sister, Debbie. She had a birthday on December 4, so I'd appreciate a prayer for her. I'm almost two years older than Debbie so I've known her for all 56 of her 39 years. She's my favorite sister. Well, yeah, she's also my ONLY sister, and, though I didn't always show it, I had much sympathy for her having to grow up with three brothers.Debbie doesn't know it, but she actually makes a sound when she rolls her eyes. It's kind of a nasally sniff that always accompanies the eye-roll, and I can hear it when we speak by telephone. I learned at age 13 that any mention of science or science fiction, and especially any mention of Star Trek, will set Debbie's famous eye-roll into motion. It works to this very day. When I told her a few months ago about "A Day Without Yesterday," I could hear her eyes roll across the miles of interstate telephone lines between us. Early this year in "February Tales," I described some of my favorite books when Debbie and I were kids growing up North of Boston. Back then, I thought my series of 35-cent Doc Savage novels were masterpieces of Western literature, and I spent a lot of time in trees reading them high above the traffic of our city street. I remember Debbie laughing hysterically when our mother yelled out the window:"If you fall out of that tree and break your leg, don't come running to me!"Debbie and I were friends as well as brother and sister, but like all brothers and sisters we also argued a lot, and one of the things we argued about was television. When I wasn't up a tree buried in a book, I was bedazzled by science fiction TV shows, and especially by Star Trek which debuted when I was 13 in 1966. Most families had only one TV back then, so Debbie's eyes would always roll when I would open negotiations to reserve the TV for the absolute must-see show of the week: Star Trek - "its five-year mission: to explore new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before!"

Early this year in "February Tales," I described some of my favorite books when Debbie and I were kids growing up North of Boston. Back then, I thought my series of 35-cent Doc Savage novels were masterpieces of Western literature, and I spent a lot of time in trees reading them high above the traffic of our city street. I remember Debbie laughing hysterically when our mother yelled out the window:"If you fall out of that tree and break your leg, don't come running to me!"Debbie and I were friends as well as brother and sister, but like all brothers and sisters we also argued a lot, and one of the things we argued about was television. When I wasn't up a tree buried in a book, I was bedazzled by science fiction TV shows, and especially by Star Trek which debuted when I was 13 in 1966. Most families had only one TV back then, so Debbie's eyes would always roll when I would open negotiations to reserve the TV for the absolute must-see show of the week: Star Trek - "its five-year mission: to explore new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before!"

Yes, it's finally out in the open! I was a "Trekker." That's "TrekkER" as opposed to "TrekkIE!" The difference is subtle but important. A Trekker is a Star Trek fan who never crossed the line by attending a Star Trek Convention, a sign of shameless fanaticism about it all. I was also a faithful fan of every one of Star Trek's subsequent emanations. My all-time favorite was Star Trek: Deep Space Nine which (yes, I'm now blushing!) first aired in 1993 when I was forty. It was a family joke that I became a priest only because StarFleet Academy didn't acknowledge my 1969 application for admission.ALIENS IN OUR LIVING ROOMBack in 1966, to make matters worse (for Debbie, at least) our family had the only color television on our block. We were by no means privileged. Our father brought it home that year as a Christmas bonus from his boss. I remember the day we first plugged it in. We quickly became the popular kids in the neighborhood!"This means," my 12-year-old sister tactlessly proclaimed, "that every nerd in the neighborhood will be in our living room for Star Trek." Debbie had to admit, at least, that Star Trek was far better in color. We discovered, for example, that only the crew members wearing red shirts were done in by aliens each week, and the slightly green tinge of Mr. Spock's skin made us wonder if perhaps Leonard Nimoy might really be Vulcan.In the inglorious world of nerdology, Star Trek was a sort of rite of passage. Just a year earlier, when I was 12 in 1965, Lost in Space captured our imaginations and primed us for the far more sophisticated Star Trek. Today, Lost in Space is a cult classic known for its campy plots, laughable scripts, bad acting, and ridiculous sets.

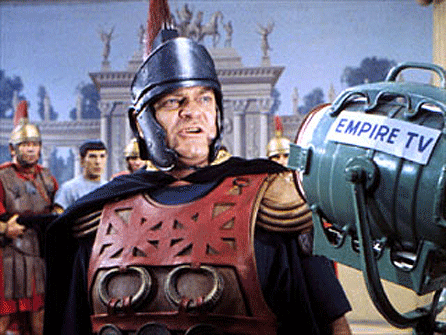

I suppose it's a good sign that I saw some clips from it recently - and - like revisiting the Doc Savage books of my childhood in "February Tales" - I thought it was just awful. Back in 1965, however, Lost in Space was gripping drama, and my friends and I compared notes each week. A year later in 1966, Star Trek was in - and in color! - and Lost in Space was out. "Oh, the pain! The pain!" as the evil Doctor Zachary Smith would complain each week.TO BOLDLY GO WHERE NO NETWORK HAS GONE BEFORELest you ever doubt the power of television to shape minds - for better or worse - there was a single episode of Star Trek that I watched at age 13 and remember vividly 44 years later. Week after week, I watched Star Trek while sitting on our living room floor with three or four members of "the nerd herd." as Debbie called my friends back then.The end of every Star Trek episode found us chattering excitedly about the plot before everyone headed for the door for curfew because it was a school night. But this one episode left us all in stunned silence, pondering far deeper mysteries than the points on Spock's ears. It was an episode entitled "Bread and Circuses," written by Star Trek creator and visionary, Gene Roddenberry, and Gene L. Coon, a frequent scriptwriter for the series. Bear with me, please, while I outline the plot:(Captain's Log, stardate 4040-7): Captain Kirk (William Shatner), Mr. Spock (Leonard Nimoy), and Dr. McCoy (Deforest Kelley) beamed down to the surface of Planet 892-IV to investigate the wreckage of another StarFleet ship that had been missing for years. They discovered that the planet's civilization evolved much like Earth's, except that the Roman Empire survived and still dominates the planet and its culture, but during the equivalent of Earth's 20th century. An evolving media called "television" had consumed the culture, and the brutal spectacles of the Roman Empire played out in arenas before TV cameras and riveted masses of viewers each week. It was a bit like American Idol, but with swords and shields instead of singing voices.Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy were quickly arrested on the planet, and imprisoned by Roman legions. To make a long story short, they ended up fighting for their lives in the Roman arena alongside slaves and other captives arrested for their membership in a group called the "Children of the Sun." They were persecuted by the Roman Empire for their outlawed beliefs in peace and brotherhood, and for having an icon besides Caesar. They were mercilessly mocked for going to their deaths in the arena because they refused to fight.

An evolving media called "television" had consumed the culture, and the brutal spectacles of the Roman Empire played out in arenas before TV cameras and riveted masses of viewers each week. It was a bit like American Idol, but with swords and shields instead of singing voices.Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, and Dr. McCoy were quickly arrested on the planet, and imprisoned by Roman legions. To make a long story short, they ended up fighting for their lives in the Roman arena alongside slaves and other captives arrested for their membership in a group called the "Children of the Sun." They were persecuted by the Roman Empire for their outlawed beliefs in peace and brotherhood, and for having an icon besides Caesar. They were mercilessly mocked for going to their deaths in the arena because they refused to fight.

In an Empire prison cell, Mr. Spock and Dr. McCoy got into their weekly philosophical discussion about the plot. This time, it was about what they thought were aimless "sun worshippers." As always, their debate degraded quickly into a personal dispute. I wish I’d had this classic exchange last week to add to my post, "Saint Gabriel the Archangel":Dr. McCoy: "Just once, I'd like to be able to land someplace and say, 'Behold, I am the Archangel Gabriel.'"Mr. Spock: "I fail to see the humor in that situation, Doctor."Dr. McCoy: "Naturally! You could hardly claim to be an angel with those pointed ears, Mister Spock. But say you landed someplace with a pitchfork . . . ”Well, maybe you had to be there. But as it turned out, the exchange was a clue to the true plot. Back aboard the orbiting U.S.S. Enterprise, Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott, now in command, dutifully refused to intervene with 24th Century technology when he learned that Kirk, Spock, and McCoy were to be executed in the arena. The reason was Star Trek's “Prime Directive” that forbade using technology to alter a planet's natural history. Being led into the arena, Kirk was warned by a Roman soldier: "You bring this network's ratings down and we'll do a special on you!”In the end, Mr. Scott decided that creating a simple power blackout to knock out the TV coverage and its high ratings might give Kirk, Spock and McCoy a fighting chance. It worked, and they were swiftly beamed back aboard the Enterprise. Captain Kirk, Mr. Spock, Dr. McCoy, and the Prime Directive were all safe, while the Empire and its rabid TV audience had no clue what happened.Later on the bridge of the Enterprise, Captain Kirk ironically pointed out that the violence, and concern for ratings over art, was a lot like television on 20th Century Earth, but we thankfully evolved out of it. Well . . . we’re still waiting! We can only hope.More importantly, however, Communications Officer Uhuru pointed out that she also had been monitoring the planet's TV broadcasts, and the landing party had it all wrong. The martyrs in the arena were not "Children of the Sun,” they were "Children of the Son” - and they did not give their lives for the Sun in the sky, but “for the Son of God." Then, as always, William Shatner’s Captain Kirk ended the episode with the last word:

"Caesar and Christ! They had them both! And the word is spreading only now. Oh, to be there to see it happen all over again!”

Then the cameras zoomed out upon a stunned and silent Enterprise crew pondering where they had been and what they had seen - and perhaps some nervous network executives just off-camera waiting for the phones to start ringing. This was the sixties, after all, and proclaiming Christ while poking fun at television was not exactly a typical network ploy. It was usually the other way around! Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek's visionary creator, personally wrote the script for this episode, and if he is remembered for nothing else, his courage was outstanding.In "A Day Without Yesterday," I described my 1985 exchange with Cornell physicist Carl Sagan after reading his spectacular novel, Contact. I wrote that the discovery of intelligent life elsewhere might not be nearly the challenge for Catholics that it was for the fundamentalist Protestants of his novel. We Catholics presume the need for redemption, and for Christ, no matter where souls exist - or when. Gene Roddenberry did, too. So did Captain Kirk, and it gave the nerd herd a new frame of reference to ponder for decades to come.Live long and prosper, Debbie. And Happy Birthday!