Prophets on the Path to Peace

I had a visit a few weeks ago from Emily, my 23 year old niece. I was struck by how happy and settled she is. We reminisced over coffee about family memories and the significant events of Emily’s childhood growing up in my sister’s home near Boston. We laughed and laughed at the quirks and quagmires of our family.Emily had read my first post of Advent last month, “A Corner of the Veil,” and spoke of how very moved she was. Emily revealed to me that it was she who took the celebrated photograph of my mother, her beloved grandmother, in Newfoundland, the photo that is described in that post. I had not known this, and it’s an important element of that story for me.For much of our visit, we also spoke of the last decade and its impact on Emily and her generation. I could see how very different Emily’s adolescence was from my own. In my November 18 post, “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” I wrote of the tumultuous decade from 1963-1973. It was the decade of my adolescence. The decade that both formed and transformed my conscience. The events of that decade are in the minds of those of us who lived it, linked in a sort of domino effect.Those dominos began to fall, in my mind, with the 1963 assassination of President John. F Kennedy when I was ten. The stream of dominos seemed to end one decade later with the US Supreme’s court's 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade when I was twenty.There was so much that happened in the middle that entire volumes have been written to assess that decade’s impact on American life and culture, and, for Catholics at least, what it now means to be a Catholic in America in a new millennium. That assessment is ongoing, and I cannot pretend to add anything to it. I can only comment on it.Right in the middle of that decade, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. His life was taken in 1968, four years after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his heroic commitment to social change through nonviolent recourse and discourse.

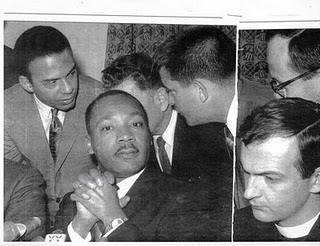

I had a visit a few weeks ago from Emily, my 23 year old niece. I was struck by how happy and settled she is. We reminisced over coffee about family memories and the significant events of Emily’s childhood growing up in my sister’s home near Boston. We laughed and laughed at the quirks and quagmires of our family.Emily had read my first post of Advent last month, “A Corner of the Veil,” and spoke of how very moved she was. Emily revealed to me that it was she who took the celebrated photograph of my mother, her beloved grandmother, in Newfoundland, the photo that is described in that post. I had not known this, and it’s an important element of that story for me.For much of our visit, we also spoke of the last decade and its impact on Emily and her generation. I could see how very different Emily’s adolescence was from my own. In my November 18 post, “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” I wrote of the tumultuous decade from 1963-1973. It was the decade of my adolescence. The decade that both formed and transformed my conscience. The events of that decade are in the minds of those of us who lived it, linked in a sort of domino effect.Those dominos began to fall, in my mind, with the 1963 assassination of President John. F Kennedy when I was ten. The stream of dominos seemed to end one decade later with the US Supreme’s court's 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade when I was twenty.There was so much that happened in the middle that entire volumes have been written to assess that decade’s impact on American life and culture, and, for Catholics at least, what it now means to be a Catholic in America in a new millennium. That assessment is ongoing, and I cannot pretend to add anything to it. I can only comment on it.Right in the middle of that decade, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. His life was taken in 1968, four years after being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his heroic commitment to social change through nonviolent recourse and discourse. The April 2009 issue of First Things has some terrific photographs of Fr. Richard John Neuhaus marching alongside the Rev. Dr. King in a unity of purpose and mission. In a celebrated book published posthumously last year – American Babylon: Notes of A Christian Exile - Fr. Neuhaus wrote of the radical grace exemplified by Martin Luther King in his concept of “The Beloved Community,” and described by Fr. Neuhaus as a new order…

The April 2009 issue of First Things has some terrific photographs of Fr. Richard John Neuhaus marching alongside the Rev. Dr. King in a unity of purpose and mission. In a celebrated book published posthumously last year – American Babylon: Notes of A Christian Exile - Fr. Neuhaus wrote of the radical grace exemplified by Martin Luther King in his concept of “The Beloved Community,” and described by Fr. Neuhaus as a new order…

“… sought by all who know love grief in refusing to settle for a community of less than truth and justice uncompromised.”

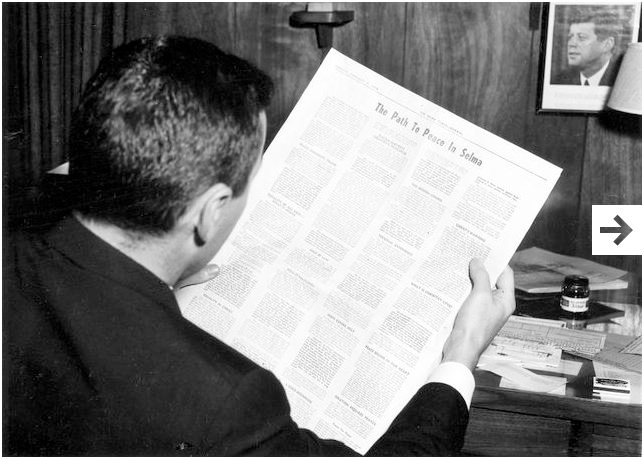

FR. JOHN CROWLEY

Prophets of peace are often best known and remembered for what they inspire in others. Martin Luther King loved America, and knew love’s grief. It was for this very reason that Fr. Neuhaus stood at his side in the march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama in 1965. There were also others in the Catholic tradition who were inspired to heroic witness by Dr. King’s example.On June 6, 2006, the Selma Times-Journal eulogized Fr. John Crowley. Fr. Crowley’s college years were interrupted by World War II. After serving two years in the U.S. Navy, he continued his studies at St. Michael’s College in Vermont. While attending graduate school in Europe, he felt called to priestly life and ministry.Fr. Crowley was ordained on June 5, 1954. We share the same ordination date, though I was but a year old when John was ordained.Ordained as a priest for the Society of St. Edmund, Fr. John taught English at his alma mater, St. Michael’s, directed his Order’s Novitiate, and served as secretary to the Minister General. Fr. John’s path was an ordinary one for a young, religious order priest.John Crowley’s true mettle came to be known in a time of great trial. In 1964, Fr. Crowley was placed in charge of his Order’s Southern Mission which included ten Alabama parishes with a base in Selma. As I described in “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” these years were the most tumultuous in American history to be a priest. Fr. John Crowley lived those years in the most tumultuous place of that decade, Selma, Alabama.In the truest spirit of Martin Luther King’s “Beloved Community” and Fr. Richard John Neuhaus’ American Babylon, Fr. Crowley simply could not “settle for a community of less than truth and justice uncompromised.” At the height of racial conflict of 1965 Selma, he worked quietly but forcefully to build bridges linking the forces within a community in the throes of violence. On February 7, 1965 – when Selma was in the midst of civil disruption - Fr. Crowley took out a full page ad in the Selma Times- Journal to outline his landmark contribution to civil rights and civil justice. His essay, “The Path to Peace in Selma,” urged the white community to speak out against the injustice of segregation.It was a brilliant and courageous essay, all the more so by its timing – a timing that helped bring light instead of heat to the chasm of division that embroiled Selma. Fr. Crowley paid for his essay as an ad because the Times-Journal of 1965 would likely never have published it otherwise. The essay began with a call to our best nature:

On February 7, 1965 – when Selma was in the midst of civil disruption - Fr. Crowley took out a full page ad in the Selma Times- Journal to outline his landmark contribution to civil rights and civil justice. His essay, “The Path to Peace in Selma,” urged the white community to speak out against the injustice of segregation.It was a brilliant and courageous essay, all the more so by its timing – a timing that helped bring light instead of heat to the chasm of division that embroiled Selma. Fr. Crowley paid for his essay as an ad because the Times-Journal of 1965 would likely never have published it otherwise. The essay began with a call to our best nature:

“It is in times of crisis that good neighbors draw together more closely. They look for reassurance from each other. And they get this reassurance, plus new strength and hope for the future, when, together, they reaffirm basic spiritual values; when, together, they … make a firm resolve to apply the practical remedies that will be a cure for their ills.Selma is now in such a time of crisis. Our city’s reasonable men will strive to restore tranquility to the community, a tranquility that is the product of good order based on truth.”

With the common language of the times, Fr. John Crowley inspired by Martin Luther King wrote perhaps the most inflammatory language of the time in support of equal rights:

“Both as a man and as an American citizen the Negro has a duty to claim those rights which are fundamental to his dignity. And all others have an obligation to acknowledge those rights and respect them…. [W]e know from personal experience the truth of the Negro claims of injustice, and the evil effects of discrimination…. That is why we support wholeheartedly those non-violent efforts to obtain their full rights as Americans.”

I wonder if I would have had the moral courage to respond as Fr. Crowley did to a community at the height of such division. Like Dietriech Bonhoeffer before him responding to the Nazi regime of 1942 Germany, Fr. Crowley also chided his fellow clergy for allowing their fear of a loss of status to keep them from preaching the truth, and most courageously he reprimanded the police for placing prejudice above the law:

I wonder if I would have had the moral courage to respond as Fr. Crowley did to a community at the height of such division. Like Dietriech Bonhoeffer before him responding to the Nazi regime of 1942 Germany, Fr. Crowley also chided his fellow clergy for allowing their fear of a loss of status to keep them from preaching the truth, and most courageously he reprimanded the police for placing prejudice above the law:

“The fear of loss of pulpit has prevented many clergymen from becoming witnesses to the truth… And what a mockery… if law officers [are] pushed into excess by the vehemence of their own prejudices [and] should forget the dignity of their role.”

DRED SCOTT AND ROE v. WADE

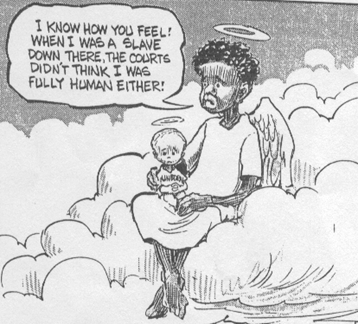

It’s difficult for my niece, Emily, to comprehend that in her uncle’s lifetime black American citizens could not vote and racial segregation was a societal norm. It’s difficult for all of us to imagine a time when people believed in their hearts that they were protecting their own rights by denying others theirs.Martin Luther King’s life was taken from him – and from us – five years before the emergence of another battle on the front of human rights, the right to life. Many people react with indignation at this argument today in the same way some bristled at the very notion of equal rights in 1965 Selma, Alabama.I am not the first person to make this argument. In 1973, after the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its divided decision in Roe v. Wade, the State of Texas joined other states in filing a petition for a rehearing before the full Court comparing the Court’s decision that an unborn human life was not a person with identifiable rights to an earlier Court’s similar opinion that Dred Scott was not a person with rights.This is a piece of American history worth knowing though many would prefer we did not know. Dred Scott was a slave in Missouri who brought suit attempting to assert his inalienable right to freedom. His claim was based on the fact that though his “Master” “owned” him in Missouri, he was first taken in Illinois which was a free state. His freedom, thus, was guaranteed because slavery had been forbidden in Illinois by the Missouri Compromise.In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote the majority opinion for the Court. In it, Justice Taney maintained that black men are not citizens of the United States and therefore, as he put it, had “no rights any white man was bound to respect.”There is a natural abhorrence to such language today, and to such a decision from our Supreme Court. But in 1857 the Court went far beyond the simple ruling that Dred Scott did not possess the rights of a citizen to sue. The decision rendered the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional thereby throwing out the U.S. Congress’s right to make territory free of slavery. The decision held that the Missouri Compromise violated the Fifth Amendment by depriving Southerners of their right to private property, i.e., slaves.That decision sounds appalling to us, but it was cheered in its day by many. It caused some, however, to assert that there is a higher moral law than the Constitution, and a higher moral authority than the Supreme Court. These voices of conscience changed minds and hearts, and, in time, the Supreme Court’s decision.

Those same arguments continue today in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade, seen by many as the nation’s most pressing and unresolved civil rights issue. Justice Blackman’s 1973 brief assigned precedence to a women’s right to privacy over an unborn child’s right to life. It is an interesting aside that Justice Blackman spent many months trying to frame his argument differently. He tried to ascertain that limiting abortion was a violation of a physician’s right to privacy, not a woman’s. Nonetheless, the State of Texas argued in the aftermath of Roe v. Wade that the decision is not, in its essence, unlike the now universally condemned Dred Scott decision.It’s an interesting argument, and some historians have cited the similar ferocious attacks that greeted both decisions and continued for decades. In the case of Dred Scott, of course, the decision was ultimately replaced with something far more morally and socially responsible. In the case of Roe v. Wade the ferocious and constant attack continues with its own heroes – or villains depending on where in the argument one stands.Without doubt, there were those in Selma, Alabama in 1965 who saw Fr. John Crowley as a villain. Today, Fr. Crowley’s photograph hangs in a place of honor in Selma’s Interpretative Center for the Selma to Montgomery March, a permanent municipal display honoring what we now know are the moral heroes of that time. The enormity of Fr. John Crowley’s courage is clear to us now. The hindsight of history tells me that he put his very life on the line for the rights of others who were disenfranchised from having a voice.We can deduce where Martin Luther King would stand on the pressing civil rights issue of this day. It is no irony that the week that begins in honor of Dr. King’s martyrdom for civil rights ends with the National March for Life in Washington, DC. Most certainly, Richard John Neuhaus was a leader in applying Dr. King’s civil rights principles to the right to life without conciliation or compromise. There could have been no acceptable compromise in the Dred Scott decision. How could there be conciliation in the denial of civil rights?As we honor Martin Luther King and Fr. Richard John Neuhaus this month, let’s add Fr. John Crowley to our prayer of thanksgiving and enduring respect. He was one of the heroes of a revolution – a moral revolution that helped save our nation’s soul. He preached neither conciliation nor violent confrontation, but rather prevailed as a champion for the truth.May God raise up others with the spirit and courage of Dr. King, Fr. Neuhaus, and Fr. Crowley.Amen.