Sex, Lies, and Videotape: Lessons from the Duke University Rape Case

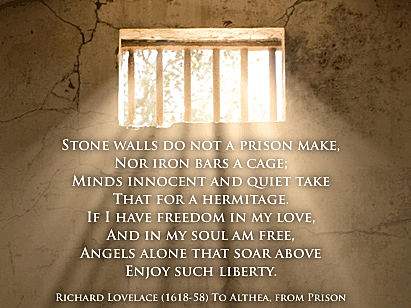

In 2007, rogue prosecutor Mike Nifong fed a "Privileged Jocks Gone Wild" story to a scandal-hungry news media, and nearly sent three innocent students to prison.In the "On the Record" section of These Stone Walls, you'll find the comments of some people who have endorsed the underdog in a steep, uphill climb toward justice. These writers have recognized that one of the daunting challenges of writing from behind prison walls is that I have no access at all to a source of information virtually every other writer in the world counts on: the Internet. It's no small handicap in a world with instant access to facts and opinions. A friend wrote that it’s like trying to keep up with a conversation using a hammer and chisel and a slab of stone when everyone else has paper and a ballpoint pen. My response time in the conversation has the effect of almost silencing me. Almost, but not quite.So I make due with what I've got. I often clip and save news stories that I think I might write about one day. With extremely limited space in an overcrowded prison, however, I have to be selective, and occasionally even have to purge my supply of news clippings. I just came across one I clipped four years ago, and it still sends a chill down my spine.On April 12, 2007, USA Today ran an unusual lead editorial headlined, "Duke rape case implodes, revealing world of injustice." Its opening salvo told the entire story:

In 2007, rogue prosecutor Mike Nifong fed a "Privileged Jocks Gone Wild" story to a scandal-hungry news media, and nearly sent three innocent students to prison.In the "On the Record" section of These Stone Walls, you'll find the comments of some people who have endorsed the underdog in a steep, uphill climb toward justice. These writers have recognized that one of the daunting challenges of writing from behind prison walls is that I have no access at all to a source of information virtually every other writer in the world counts on: the Internet. It's no small handicap in a world with instant access to facts and opinions. A friend wrote that it’s like trying to keep up with a conversation using a hammer and chisel and a slab of stone when everyone else has paper and a ballpoint pen. My response time in the conversation has the effect of almost silencing me. Almost, but not quite.So I make due with what I've got. I often clip and save news stories that I think I might write about one day. With extremely limited space in an overcrowded prison, however, I have to be selective, and occasionally even have to purge my supply of news clippings. I just came across one I clipped four years ago, and it still sends a chill down my spine.On April 12, 2007, USA Today ran an unusual lead editorial headlined, "Duke rape case implodes, revealing world of injustice." Its opening salvo told the entire story:

"Americans like to think that few innocent people are arrested, much less charged or convicted, and that rogue prosecutors are the stuff of fiction. Not so, the nation learned Wednesday, when the already shaky sexual assault case against three Duke University lacrosse players collapsed entirely."

The case collapsed in time to save three innocent young men from a criminal trial, almost certain conviction, and years or even decades of wrongful imprisonment. The problem from the start was not that there was evidence against them. There wasn't any biological evidence or any clear evidence at all beyond the word of a woman who claimed to be a victim of rape by the three privileged Duke students.The greatest tragedy of this case, according to the USA Today editorial, is the fact that real victims of rape and other sexual assaults may not be so readily believed in other cases. This case collapsed not because evidence was put to the test and refuted, but because the family of at least one of the accused had the means to push back against the state's relentless prosecutorial steamroller. But it didn't collapse in time to save Duke University students, David Evans, Collin Finnerty, and Reade Seligmann from a year-long campaign of vilification and one-sided rhetoric reflecting a shameless presumption of guilt, not only by prosecutors and the news media, but by representatives of Duke University itself. A number of Duke's "socially conscious" faculty fueled race and class tensions created by the claims by publicly presuming the guilt of the accused young men in their rush to acknowledge and apologize to the "victim." It was an irresponsible bow to political correctness. As the USA Today writer put it,

"Due process and the presumption of innocence got lost in the uproar."

THE NIFONG FACTORAdded to that uproar were the tactics of a now disgraced and disbarred state prosecutor. Former Durham County District Attorney Mike Nifong was more interested in throwing "gasoline on the fire," according to USA Today, than gathering evidence. He ignored the complete lack of evidence, not to mention the accuser's constantly changing story, and vowed to continue his prosecution even after the case fell apart. This prosecutor suppressed exculpatory evidence, hid it from defense lawyers, and held repeated news conferences to keep the momentum of judgment going in the court of public opinion.Co-opting some Duke faculty into pre-trial condemnation of the accused was a tactical advantage for prosecutor, Mike Nifong. The result was a trial-by-media that should sound hauntingly familiar to Catholics reeling from the Church's own sex scandal. When it was all over - in the rarest of examples of justice redirected toward an unjust prosecutor - Mike Nifong was fired from his office, convicted of contempt, and disbarred from the practice of law. In dismissing the case, the North Carolina Attorney General declared that the students were victims of a "tragic rush to accuse."

The young woman who brought the false claims, and allowed the prosecutor to run with them, faced no consequences at all.

Four years later, she was herself indicted on an unrelated charge of attempted murder, and is today awaiting her own trial. It's easy to be angry with this accuser, but in so many ways she became a manipulated pawn for those who wanted to use the Duke rape story for agendas of their own; not least among them, prosecutor Mike Nifong's political ambitions.As the USA Today editorial writer pointed out, the Duke case was "a telling lesson in the ability of prosecutors to manipulate grand juries." The three young men were indicted and bound over for trial despite a total lack of evidence because, as one of my own attorneys has put it,

"Indictment is not a measurement of guilt, or even evidence. A smart prosecutor could get a grand jury to indict a ham sandwich."

"IT'S DEJA VU ALL OVER AGAIN!" (Yogi Berra)Only someone who has been accused and faced a one-sided trial can truly appreciate stories of false accusation and wrongful imprisonment. When the Duke case was over, David Evans, Collin Finnerty and Reade Seligmann held a press conference of their own. The experience opened their eyes, they said, to the fact that innocent people in America can be railroaded. No one in this case is saying that these three defendants were perfect angels. In the end, they were guilty of what was clearly raunchy behavior, and the USA Today editorial made that clear.Reade Seligmann added that the case exposed him "to a tragic world of injustice I never knew existed." Without the means to hire talented and expensive lawyers, the three concluded, they might well have ended up spending 30 years in prison for a crime they did not commit.Their statement reminded me of something I wrote in "Pop Stars and Priests" last year. Daniel Henninger, Deputy Editor of The Wall Street Journal Editorial Page, reflected on the collapse of the molestation case against pop star, Michael Jackson in spite of its vast media frenzy and its own relentless prosecutors ("A Freaky Culture's Peter Pan," June 3, 2005):

"If Michael [Jackson] walks, I'll wonder if any of the many convicted Catholic priests similarly charged were in fact innocent but found guilty because they couldn't push back against the state's relentless steamroller."

I've quoted this statement by Daniel Henninger before, but I don't think I can quote it enough. The accounts of wrongful conviction and the wreckage of innocent lives in the U.S. justice system seem to have no end to them. In "Why Accusers Should Be Named," the second installment of my three-part post, "When Priests Are Falsely Accused," I described a panel of wrongfully imprisoned and exonerated men who shared their stories on CNN's "Larry King live" on October 6, 2010. They spoke of something that riveted me to the screen. As the years and decades of their lives passed by in prison, they did not give up despite many moments of what felt a lot like despair as statements like "that's what they all say" were thrown in their faces whenever they asserted their innocence.Have another look, please, at my post, "The High Cost of Innocence" for a sense of just what a claim of innocence extracts from its victim. I don't know words that can adequately convey this to Catholics, but every prisoner I have spoken to in the last 17 years agrees. It's far easier to be guilty in prison than to be innocent in prison. It's far less costly, and guilty prisoners serve far less time. I have known a few men who I was convinced were innocent, but motivated by the relentless pressures of prison to hide that fact. Many readers know that I could have left prison 15 years ago if I was really guilty. I would have spent far less time in prison, and I would have spent it in far more comfortable conditions, with far less stress, had I actually been guilty.The Duke University rape case - as it came to be called in the news media - has special meaning for those similarly accused but wrongly convicted. Prosecutor Mike Nlfongs's manipulation of what the public perceives has been no different in the story of accused Catholic priests. Yes, of course there were real victims of abuse, and that fact is tragic. But like Mike Nifong's "Privileged Jocks Gone Wild" story, the fact that victims exist is not evidence that every claim of victimhood is true.The cold, hard fact is that many of those who accused priests have surfed the wave to commit fraud and larceny. As I wrote in "When Priests Are Falsely Accused," there is no crime for which more guilty men never face justice, and there is no crime for which more innocent men are falsely accused and wrongly convicted. This point was made in a recent comment on my post, "Are Civil Liberties for Priests Intact?" The comment was from a police officer of over 25 years who wrote that she has dealt with more false allegations of sexual abuse than real cases.THE TIP OF AN ICEBERGBut I still hope Catholics may get a hint about what's really going on from the vast stories of wrongful conviction and exoneration that keep popping up in the news. Writing for Time Magazine ("Resumed Innocent," May 31, 2010) writer Nathan Thornburgh pointed out that hundreds of prisoners - most convicted of sexual assault - have been exonerated and released in recent years because preserved DNA evidence proved that the wrong person was convicted and in prison. Almost all of them were released because of the work of The Innocence Project and its founder, Attorney Barry Scheck. Mr. Scheck and many state prosecutors now disagree about the full meaning of the hundreds of DNA exonerations. Many state prosecutors still routinely fight against allowing defendants who maintain their innocence to continue to fight their convictions. In the Time article cited above, Attorney Scheck pointed out:

Mr. Scheck and many state prosecutors now disagree about the full meaning of the hundreds of DNA exonerations. Many state prosecutors still routinely fight against allowing defendants who maintain their innocence to continue to fight their convictions. In the Time article cited above, Attorney Scheck pointed out:

"Less than 10% of criminal cases have any biological evidence . . . So what about the other 90%? This is an iceberg. These cases are the tip."

In May, 2011, John Bacon writing for USA Today described yet another among these hundreds of cases ("DNA test brings freedom after 27 years in prison," May 13, 2011). Dallas County resident, Johnny Pinchback, age 55, went to prison at the age of 28 for a rape charge that he had nothing to do with. As he walked out of prison exonerated after 27 years, he told a reporter that his immediate plans were to visit his mother, and then help fight for other prisoners wrongly convicted.Johnny Pinchback is the 22nd man in Dallas County alone to be freed after DNA proved his wrongful conviction for sexual assault. There have been hundreds nationwide. I've written of similar accounts in two other posts, "The Eighth Commandment" and "Walking Tall, The Justice Behind the Eighth Commandment." Some of the wrongful conviction websites that have endorsed and linked to These Stone Walls are filled with accounts of the tyranny of false accusation and the horror of being wrongly imprisoned. You would do well to spend some time at the National Center for Reason & Justice, Opus Bono Sacerdotii (Work for the Good of the Priesthood) and other sites listed here at "Related Links."EVIDENCE OF EVIDENCE"About.com," an on-line venture of The New York Times, has a Catholicism page that reviews various Catholic media, old and new. Its readers recently voted the National Catholic Register as the best Catholic newspaper. In About.com's review of These Stone Walls, Catholic moderator Scott P. Richert wrote:

"Fr. Gordon MacRae's blog, These Stone Walls, is a timely reminder that, for accused Catholic priests today, the presumption of innocence is often nonexistent. Without minimizing the horrors of clerical sexual abuse, Father MacRae reminds us that the putative victim is not always the real one."

That lesson is demonstrated nowhere more powerfully than in the Duke University rape case of 2007. It's a lesson for Catholics reeling from our own scandal. In an upcoming post on These Stone Walls, I plan to venture one more time into a case that has brought many Catholics to the brink of tolerance and seriously eroded hope for a just resolution of the priesthood scandal anytime soon. I plan to write again of the case of Father John Corapi who, like any accused priest today, faces an added burden in the process of defending himself: a punishment that actually precedes any determination of guilt.Meanwhile, I am grateful to Attorney Barry Scheck, Ryan A. MacDonald, and other champions of justice who continue to see through media hype to get at the solid, sordid truth. They often do so against many obstacles, not the least being a prejudice in favor of the judicial system. Bill Donohue at The Catholic League told me of efforts by one "prominent Catholic writer" to dissuade him from supporting me. It's just as well that I don't know the identity of the writer. Ryan MacDonald recently wrote to me of his exchange with another "prominent Catholic writer," perhaps even the same one. Regardless, I will not use these pages to embarrass him by printing his name, but here was his response to Ryan's request that he look more deeply at this case. I found this exchange to be discouraging, but, sadly, not surprising:

Catholic Writer: "I, too, am troubled by the case of Father MacRae, but I do not share your conviction that he is innocent. I judge the merits of the case by its evidence."Ryan MacDonald: "I am aware of no evidence of guilt at all in this case, and a growing volume of evidence that these claims of abuse never took place at all. If you know of evidence I don't, please tell me about it."Catholic Writer: "Actually, I'm not aware first hand of any evidence against him, but I refuse to believe that a prosecutor and a judge would send a man to prison with anything less than clear and compelling evidence. And besides, his diocese said he was guilty even before his trial."

So let's be clear about this: the absence of evidence is evidence of evidence. How does an innocent defendant, especially a Catholic priest, defend himself against such a presumption? Fortunately, for three young alumni of Duke University, at least, the nation was willing to cease its media hype long enough to hear real evidence, and there was none. Those men are free, but the USA Today editorial commenting on that fact ended with an urgent question. It's a question I'll explore again soon as I apply it to Father John Corapi:

"It all brings to mind the question that former Labor Secretary Raymond Donovan famously asked 20 years ago when he was acquitted of fraud and larceny charges":"Which office do I go to to get my reputation back?"

![]()