Sweetest Mother, continue to teach me about the interior life.

May the sword of suffering never break me.

O pure Virgin, pour courage into my heart and guard it.

— Prayer of St. Faustina to the Sorrowful Mother (Diary of St. Faustina, 915)

Pornchai Moontri remembers he was carrying his knife, and he remembers struggling to get out from under the weight of a man much heavier than he. He doesn’t remember much else other than that he was out of his mind from years of rage and a night of too much drinking.

But this is what authorities in Bangor, Maine, pieced together: Pornchai, a native of Thailand, stumbled into a Shop ‘n Save supermarket in March 1992, proceeded to take beer from the refrigerator, open it, and drink from it. When confronted by a store manager, he tried to flee. Outside in the parking lot an altercation ensued, and a 27-year-old Shop ‘n Save employee was killed with a knife wielded by Pornchai.

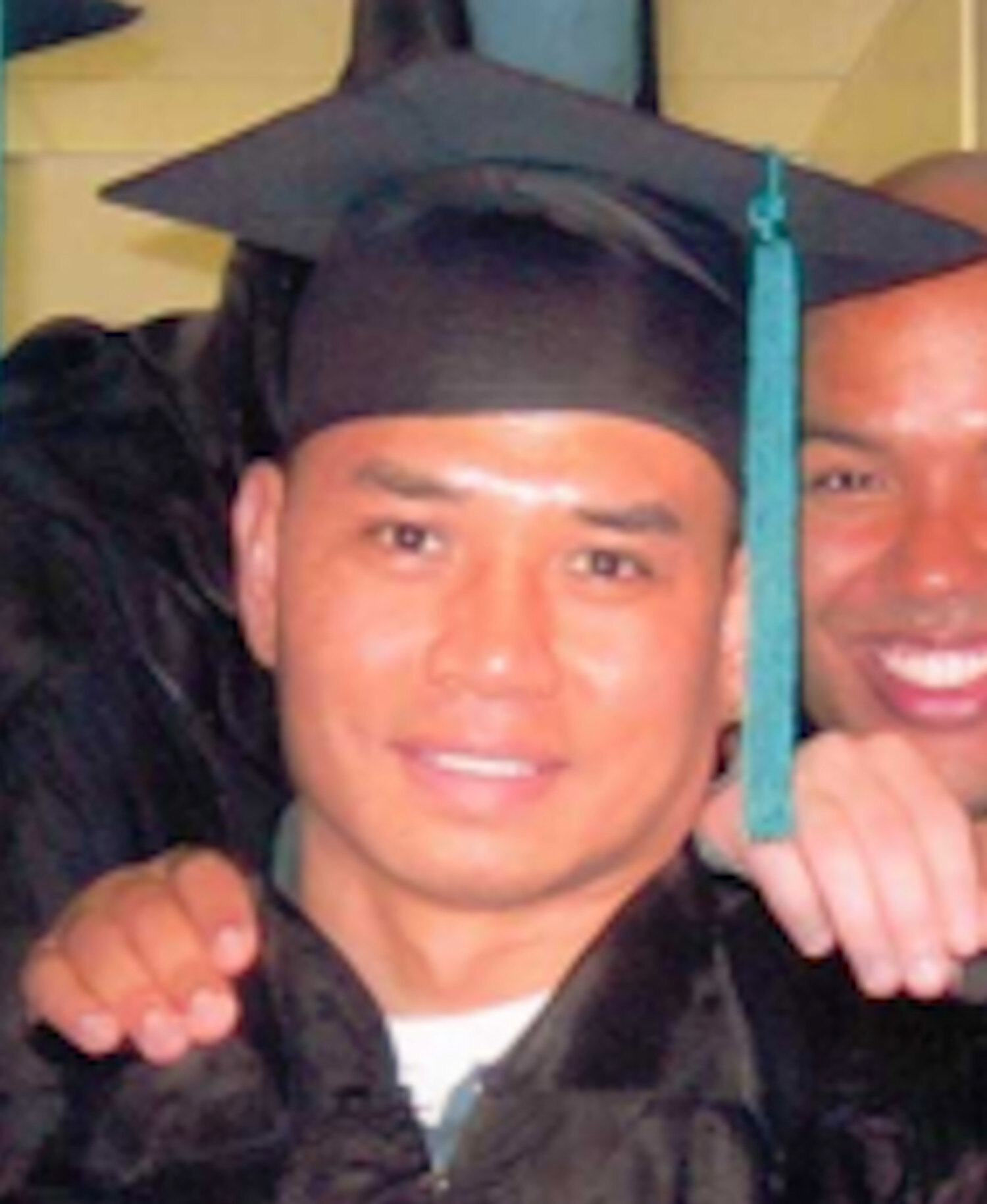

Pornchai was sentenced to 45 years in prison. He was 19 years old at the time. He’s 39 years old today. Inside New Hampshire State Prison, Pornchai is inmate #77948, a number not a name. But God numbers every single hair on our heads, as Pornchai has learned from Scripture (see Lk 12:7), so how much more God must cherish every single one of His children, including — and most especially — the most broken, those in most need of His mercy.

It took Pornchai years of self-righteous anger, years of self-pity, misery, and hopelessness, before he was graced with the realization that God is real, that He is Mercy Incarnate. This realization culminated when, in the prison chapel, he received the Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation on April 10, 2010. The following day — the Feast of Divine Mercy Sunday — he received his First Holy Communion from the Most Rev. John McCormack, Bishop of Manchester, New Hampshire. The date was no accident.

In a series of revelations to St. Maria Faustina Kowalska in the 1930s, the Lord called for this special feast day. “On that day the very depths of My tender mercy are open,” Christ promised. “… The soul that will go to Confession and receive Holy Communion shall obtain complete forgiveness of sins and punishment. On that day are opened all the divine floodgates through which graces flow. Let no soul fear to draw near to Me, even though its sins be as scarlet” (Diary of St. Faustina, 699).

“In the course of my life,” Pornchai says, “for what I have done and what has been done to me, I do need God’s mercy, and He has given it to me.”

That speaks volumes coming from a man who has spent more than half of his life behind bars.

In a trial that lasted little more than a week, the jury sided with the prosecutor who argued that Pornchai had a “depraved indifference to the value of human life,” as one press account reported.

The jury found him guilty of murder. But the jury heard nary a word about the life Pornchai led before that terrible evening. His court-appointed attorney said nothing of the victimhood Pornchai, himself, withstood long before his crime was committed. Nothing about how, two years after his birth in northern Thailand in 1973, Pornchai’s mother abandoned him. Nothing about how he never attended grade school.

Nothing about how his mother re-emerged with a new husband, an American, when he was 11 years old and took him to the United States against his will. Nothing was said about his assertion that his stepfather repeatedly raped him over a period of three years. Nothing about how in the racially monochromatic Maine of his youth, he was called “gook” by his classmates who did everything they could to make him feel like an outcast because of his appearance and stupid because of his broken English.

Nothing about how, at the age 14, anger was all he had. He left home and lived on the streets of Bangor. He was placed in a school for troubled teens and promptly kicked out for fighting. He went back to living in the streets and felt it prudent to carry a knife for self-protection.

By the time he got to prison, it wasn’t self-protection he sought. Rather, it was self-destruction. He was remorseful for the murder of an innocent man. He could hardly bear to think about it. Just so the pain could end, he did everything within his power to provoke fellow inmates into killing him.

“Really, I wanted them to beat me to death or stab me with a homemade knife,” he says. “To me at the time, I had no reason to live.”

Because of his violent tendencies, Pornchai was placed into solitary confinement many times for a combined six-plus years. What that often meant was spending 23 hours a day alone in a tiny cell. On his first day in “solitary,” he entered the cell, and it was so filthy he took the advice of a neighboring inmate to set off the fire sprinklers in order to hose the cell down. It worked, more or less, but it also prompted the first of many instances whereby he was pulled from his cell and subdued by men in full riot gear, his limbs bent backwards nearly to the point of snapping.

He slept on a cement cot. He had 45 minutes of recreation time per day where he was brought to a five-feet wide by eight-feet long chain-link cage. He was given a dab of toothpaste each day to brush his teeth using his finger. He was not permitted to have a toothbrush. Is it possible to kill oneself with a toothbrush?

He probably would have tried if given the chance.

Without a second thought, Pornchai would have cut an artery or hung himself if he had the means.

Editor’s note: The prisoners in this Frontline documentary are all known to Pornchai, who has now entered an entirely different life: Frontline Solitary Nation, a production about the solitary confinement “supermax” unit of the Maine State Prison where Pornchai Moontri spent thirteen years before being transferred to the New Hampshire prison.

He had access to three books per week. He chose the thickest in order to make them last. Those books included a peculiar combination of Stephen King novels and the Bible, which he said he read cover to cover twice. Pornchai could relate to the horror, violence, and psychological depravity depicted by Stephen King in novels often set in — of all places — small-town Maine. As for relating to the Bible — not so much. Hope and salvation were the stuff of fiction, not much different than a haunted 1958 Plymouth Fury in the King novel Christine or the monster lurking in a small town’s sewers in IT. Still, anything that could help drown out the madness of prison life and that of his own mind was worth the effort.

“Inmates would do anything to try to break up their day and entertain themselves,” Pornchai says. “Some played with their own urine and feces, and others used those as weapons, throwing them at the guards after calling their names to get their attention.”

He says he survived those early years of his incarceration by doing push-ups — as many as 1,500 a day — “and venting as much of my anger, frustration, and energy as possible into physical fitness.”

He says, “In a way, this also worked against me. The more physically strong I became, the more I was treated like a dangerous animal.”

It was in solitary confinement where he learned of the death of his mother. She was murdered, in Guam, where she had relocated.

“I was now alone in my rage,” Pornchai says. When he finally was released for good from solitary confinement, he says, he had at least as many psychological problems as the day he entered prison.

“I was angry, depressed, often hostile, and anti-social,” he says.

He was transferred from the prison in Maine to New Hampshire State Prison, and he viewed the transfer as an opportunity for “a new beginning.” He was placed within the general prison population, and his urge to commit violence had subsided. Eventually, he formed a friendship that changed his life.

It was with a Catholic priest.

Through a fellow inmate, Pornchai met the Rev. Gordon MacRae, a down-to-earth, straightforward spiritual man and prolific writer who seemed to have a lot of answers to a lot of questions. Is there a God? Who is He? How can we be sure? Why should we trust?

Father Gordon, 59, was convicted in 1994 on five sexual assault counts that have since been called into question, including by The Wall Street Journal whose two-part series in 2005 brought national attention to his case. He has had wide public support for his cause, including from the late Cardinal Avery Dulles, who encouraged Fr. Gordon to continue writing, which he does through a website, thesestonewalls.com (now beyondthesestonewalls.com), administered by a friend from outside of prison.

Pornchai had no idea who he was dealing with, and he and Fr. Gordon’s first meetings were not particularly transcendent. Rather, they were all business.

“I was real hostile and told [Fr. Gordon] I just wanted him to help me get transferred to a prison in Bangkok, Thailand,” Pornchai says.

Father Gordon told him to be careful what he asked for. “I won’t help you pursue something that will only further destroy you,” he said.

Pornchai was bewildered by this guy.

“I didn’t care if I would be ‘destroyed,’” Pornchai recalls, “so why on earth should Gordon care? I was hostile to him for a long time. I had mastered the art of driving anyone who cared away from me, but in Gordon, I had met my match.”

Indeed, in contrast to just about every inmate with whom Pornchai had come into contact, Fr. Gordon wanted nothing from him. Not a thing. And to boot, he didn’t thump his Bible, and he didn’t judge. He was — well — nice, a trait in short supply in prison.

How peculiar that was for Pornchai. What a stark contrast to the loss and emptiness in his own life. Still, turning with trust to another person carried great risks. Why? Because trust could leave Pornchai vulnerable. He had spent most of his life standing in the debris of some form of broken trust. Trust in his family. Trust in his peers. Trust in the justice system. Trust in himself. He had learned long ago not to trust anyone or anything. It was too risky. Plus, he was still acclimating to his “new beginning,” his sharp transformation from depression, anxiety, self-hate, guilt, and fear. He was still adjusting from a life of misery to one of mere unhappiness.

Within a few months of meeting Fr. Gordon, Pornchai was moved into the same unit as his. The two became fast friends and eventually cellmates — and the trust blossomed. “By patience and especially by example, Gordon helped me change the course of my life,” Pornchai says. “He is my best friend and the person I trust most in this world.”

The two share a 96-square-feet cell that serves as living room, bedroom, kitchen, and toilet. The cell’s built-in mirror sits over the sink. The mirror is warped, like one of those carnival fun-house mirrors. In the morning, when they lean into it to wash or shave, their faces look misshapen. In a way, it’s a cruel joke. In prison, you are condemned to hold the proverbial mirror to yourself. And if you’re not careful, a distorted self-image stares right back at you.

Pornchai doesn’t fall for it anymore. For him now, a warped mirror is just a warped mirror, another indignity of prison life. Besides, when he leans in close enough — to his own reflection, to his own heart — the distortion diminishes. He can see himself the way others now see him. Eyes that once smoldered with coiled rage now sparkle with purpose and compassion. He laughs when he describes the reaction he gets now from prisoners who knew him back before his conversion.

“They now see a man who, despite the pain and difficulty of being in prison, is at peace,” he says.

Pornchai says Fr. Gordon never pushed him into becoming Catholic.

“He never even brought it up,” Pornchai says. “I was pulled to it by the force of grace and the hope that one day I could do good for others.”

Through Fr. Gordon, Pornchai discovered the saints and the Blessed Mother. In the saints, particularly Maximilian Kolbe, he discovered what it means to truly be a man, what it means to be tough. Toughness isn’t carrying a knife and brandishing it against those he perceives as a threat. Toughness isn’t getting beaten to the point of near death and not caring about it. A man doesn’t seek to destroy other men. A man doesn’t hold his own needs above the needs of others. A real man is selfless. In St. Maximilian Kolbe, who certainly knew what it was like to be stripped of his humanity and dignity, Pornchai finds recourse because Kolbe never caved in to despair. He professed his love for God, and there was no pussyfooting around about it. In 1941, at Auschwitz, he gave his life to save that of another man. That’s manhood. That’s tough. And that’s why Pornchai took the name Maximilian as his Christian name when he was baptized. Modeling himself on Maximilian, Pornchai now reaches out to fellow prisoners who are having a difficult time, including those in danger from other inmates. Some prison guards now steer vulnerable inmates toward Pornchai and Fr. Gordon.

“They know that we’ll show them the ropes and how to do the right things to avoid creating hardship for themselves, for other inmates, and for the guards,” says Pornchai.

In the Blessed Mother, Pornchai discovered what it means to say yes to God. She is his “Mama Mary.” When the archangel tells Mary that she is to bear the Son of God and name Him Jesus, she surrenders herself completely to the Divine plan: “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word” (Lk 1:38). She says yes, despite the implications for her future — her life’s plans would be shattered. Yes, despite the danger to her — a Jewish woman pregnant out of wedlock could be stoned to death. Yes, despite the awesome responsibility — the call to be the Mother of the Son of God, the Savior of the world.

That’s faith. That’s no fooling around.

Even when surrounded by doubters, Mary remained steadfast in her faith — including at the most critical moment, on Calvary, when promises made at the Annunciation didn’t seem to be coming true.

Was such acceptance of God’s will easy? No, and it isn’t for Pornchai either. But he did things his own way for years, and where did that lead? After all he went through, surrendering to God only made sense. He could surrender all those fears and all the burdens he had carried. He could accept that while society has judged him, God hasn’t.

Pornchai and Fr. Gordon keep religious images on their cell walls, including of the Blessed Virgin Mary, St. Maximilian Kolbe, and the Divine Mercy image of Jesus.

Through Jesus Himself and through these holy servants of the Lord — more rewarding than through that warped mirror — they lean in and seek their own reflections in Christ.

Pornchai has immersed himself in religious studies. He earned his Graduate Equivalency Diploma (GED). He’s excellent at detailed carpentry, including building model ships. He lives a life of prayer and performs deeds of mercy. Gifted in math, Pornchai tutors inmates who also seek to obtain their high school equivalency diplomas.

Fellow inmate, Donald Spinner, a Catholic convert, says his faith took root through Pornchai’s example.

“Pornchai, especially, has influenced so many people here,” he says. “We all expect Father G. to be a good person, but Pornchai’s life of grace is inspiring to everyone. … The cost of discipleship for me has been the loss of my selfishness. No one can be selfish in such company.”

For Fr. Gordon, Pornchai has been an inspiration, a blessing from God that has helped him on his own difficult journey. “I have never met a man more determined to live the faith he has professed than Pornchai Moontri,” Fr. Gordon says. “In the darkness and aloneness of a prison cell night after night for the last two of his 20 years in prison, Pornchai has stared down the anxiety of uncertainty, he has struggled for reasons to believe, and he has found them.”

In less than two years, Pornchai will be eligible for a commutation or reduction in his sentence. He prays for his release. It would at least give him enough time to start a new life at a relatively young age. Still, when given his freedom, he is to be immediately deported back to Thailand, a place he hasn’t been to since he was 11 and whose language he never learned to read and write. He hasn’t even heard Thai spoken for more than 25 years.

Moreover, he has no connections there. He’ll step off the plane — then what? The only thing he’s sure of is that he will step upon the land where he was born, having experienced a rebirth. From there, he hopes to serve in a ministry helping troubled youth.

“From age 11 to 32, I always felt I was alone, that no one cared and no one loved me,” Pornchai says. “I want to be able to help those who are struggling like I did. I ask in my prayers every night that God will use me as an instrument. That’s what I look forward to.”

Editor’s Note: Felix Carroll has twice won the New York Press Association Journalist of the Year Award, and is the recipient of many journalism awards from both secular and religious publications. He is currently executive editor of the renowned Marian Helper magazine.