Goodbye, Good Men: How Progressive Bishops Sabotage Vocations

Two studies show that major ideological differences between bishops and their priests and seminarians are destructive of vocations to priesthood and religious life.

June 4, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

On June 5, 2025, the day after this is posted, I mark forty-three years of priesthood. Thirty one of those years have been spent in wrongful imprisonment, and the last sixteen of them have been lived out in your presence through this blog. Reflecting on priesthood in these circumstances has always been a challenge. Even as I offered Mass alone in my cell last Sunday night, I was struck by the absolute absence of anything or anyone around me that supports even the idea of priesthood. But yet, here I am. I reached into an older post with elements that may sound a little familiar by their repetition, but it is important that I uphold them. I do not want my life as a priest to go the way of my favorite Willie Nelson song about the things I should have said and done.

Not long ago, I was surprised to be bestowed with the honor of membership in The Catholic Writers Guild. One of my first thoughts as I plugged in my typewriter today is that this might be the post that gets me kicked out. We are in one of the strangest times in the life of the Church and in the ministry of bishops and priests that we have seen in many centuries. There have been times almost as strange, but the difference is that you were kept from knowing about them.

My priesthood ordination took place on June 5, 1982 at St. John the Evangelist Church in Hudson, New Hampshire. It did not start off well. There was another candidate for ordination that year, but he fled just days before. Someone then scrambled to revise and reprint the program for the Mass of Ordination. It was presided over by The Most Reverend Odore Gendron, Bishop of Manchester. That was four bishops ago.

Like most Catholic priests in America, I was ordained on a Saturday afternoon. Unlike most, I was ordained alone. Such a thing became a more prevalent phenomenon, however, as the signs of the times began to reflect the sins of the times. In the 1970s and 1980s, fewer men found the courage for such a counter-cultural commitment as the Catholic priesthood, a response I will be presenting in a special restored post for Pentecost this week. That post will describe the story behind the story of the gathering of the Apostles at Pentecost. The Acts of the Apostles (1:13) reports that the Eleven — Judas had come to ruin — came to Jerusalem in the company of Mary, Mother of the Resurrected Jesus, to mark the Pilgrimage Feast of Weeks fifty days after the spring celebration described in the Book of Leviticus (23:15-16). Among the Greek-speaking Jews of the New Testament, it came to be called Pentecost for “fiftieth day.”

Pentecost had long been a Jewish festival but it became a Christian feast when the Holy Spirit came upon the Apostles in Jerusalem in the form of a mighty wind and tongues of fire. Immediately after, the newborn Church saw its first scandal as Peter rose to defend the Apostles against a false accusation that they were all intoxicated at 9:00 in the morning (Acts 2:15).

One of my most vivid memories of my ordination is lying prostrate alone on the floor before the altar while a choir intoned for a packed church the Litany of Saints. I had a moment of terror on that floor as I imagined my sister shouting at me from a pew several feet away, “Get up, you fool! Flee!” I later asked my sister if she actually had such a thought. “Yup, that was me.”

Thirty-one years later in 2013 Dorothy Rabinowitz was writing “The Trials of Father MacRae,” her third in a series for The Wall Street Journal. She interviewed my sister who spoke candidly with a comment that never made its way into the articles. “The Catholic Church took my brother,” my sister said, “And now look what they have done to him.”

I have written of this in past Ordination Anniversary posts, but many people have since asked me The Big Question. If I knew then what I know now, would I have joined John, the man who was to be ordained with me, in flight from this fate?

The Signs of the Times

Back in 2012, Anne Hendershott penned a research study for The Catholic World Report entitled, “Called by Name.” There were some interesting statistics analyzed in the study. In 2010 in the Diocese of El Paso, Texas, a region that is 79-percent Catholic, there were no priesthood ordinations.

In the same year in the Diocese of Lincoln, Nebraska, a region that is only 17-percent Catholic, there were seven ordinations to the priesthood. In Portland, Oregon, the population of which is only 16-percent Catholic, there were nine ordinations in 2010. Researchers suggested that areas with large Latino populations may have fewer candidates for priesthood.

That turned out to be untrue. In the Diocese of Corpus Christi, Texas in 2010 there were seven priesthood ordinations and most were Latino. But across the nation in 2010, the number of priesthood ordinations and their ratio to the Catholic population varied greatly. Something less obvious was driving this.

In 1996, then Omaha, Nebraska Archbishop Elden Curtis penned an article entitled “Crisis in Vocations? What Crisis?” He theorized with some compelling data to back it up, that the attitudes and strength of fidelity in Church leadership is the number one causal factor in reduced numbers of viable candidates for priesthood. Archbishop Curtis wrote:

“When dioceses and religious communities are unambiguous about the ordained priesthood and vowed religious life as the Church defines these calls; when there is strong support for vocations, and a minimum of dissent about the male celibate priesthood and religious life; when there is loyalty to the Magisterium; when the bishops, priests, religious and lay people are united in vocation ministry — then there are documented increases in vocations. Young people do not want to commit themselves to dioceses or communities that permit or simply ignore dissent from Church doctrine”

— Archbishop Elden Curtis

In her article for The Catholic World Report cited above, Anne Hendershott analyzed a study by Andrew Yuengert, a Pepperdine University sociologist, who tried to quantify the observations of Archbishop Curtis about the connection between priesthood vocations and the attitudes and fidelity of Church leaders. He discovered some fascinating corollaries.

Andrew Yuengert found that dioceses with bishops ordained in the 1970s had significantly lower numbers of priesthood vocations than those with bishops ordained before or later. He found that corollary to be most prominent in the ordination statistics of bishops who were characterized as orthodox or progressive. Of interest, he discovered that bishops who regularly published articles in America magazine — considered to be more liberal — fostered fewer vocations than bishops who were more likely to publish articles in The Catholic Answer, considered to be more orthodox.

There was another interesting corollary in the Yuengert study. You may remember the great controversy at the University of Notre Dame in 2009 when then-President Barack Obama was invited to give the Commencement Address and was bestowed with an honorary degree.

At the time, eighty-three U.S. bishops signed a formal statement disapproving of the University administration’s decision to bestow an honorary degree on the openly pro-abortion President Obama who worked to expand access to abortion throughout the U.S. and the world. Yuengert discovered in this another unexpected corollary: Many of the 83 bishops who signed that statement led dioceses with the highest percentages of priesthood ordinations in the country.

The Sins of the Times

I have heard many horror stories from priests ordained in the 1970s and 1980s that the seminaries they were sent to were anything but loyal to the Magisterium and supportive of priestly vocations. I have a horror story of my own that I wrote about a decade ago. It is worth repeating because it was typical of the sins of the times in the 1970s and 1980s, the era in which the decline of priesthood was set in motion.

Following my 1978 graduation from St. Anselm College in New Hampshire, I was making a transition from religious life as a Capuchin to study for diocesan priesthood. I had requested to study at St. John’s Seminary in the Archdiocese of Boston which was where I grew up. I was sent instead to Baltimore. This story took place in the fall of 1979 in my second year of graduate theological studies at St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore. St. Mary’s was at the time considered to be the most academically challenging and most theologically liberal of U.S. seminaries. It was called “The Harvard of seminaries,” but it also had a reputation for fostering — even demanding — dissent.

There were about 160 seminarians from some 40 U.S. dioceses studying for priesthood at St. Mary’s then. It had a capacity for more than twice that number, a reality that created an atmosphere of competition between national seminaries (as opposed to local seminaries like St. John’s in Boston). Though St. Mary’s has undergone a complete revision of its direction since then, in the 1970s and 1980s it was known among priests as a birthplace of theological dissent.

The atmosphere reflected that. Seminarians never wore any form of clerical attire, and would have been laughed out the door if they did. The beautiful main chapel was used for Mass only once per week — on Wednesday nights where a weekly seminary-wide liturgy took place, often hosting clown masses, experimental music (“Dust in the Wind” by Kansas was once the Communion hymn).

There were many liturgical abuses, and any refutation earned the commenter a notation of “theologically rigid” in his file. Other weekday masses were held in small groups in faculty quarters. On Sundays, seminarians were on their own, encouraged to attend Mass at one of several Baltimore parishes. Some rarely ever attended Mass at all.

In 1979, a rift of sorts formed between the seminary rector and those planning for a U.S. visit by Pope John Paul II at the end of the first year of his pontificate. In October, 1979, Pope John Paul II spent six eventful days in the United States, visiting Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, Iowa, Chicago, and Washington, D.C.

One of the highlights of the visit was Pope John Paul’s address to the United Nations General Assembly on October 2, 1979. He stressed the theme of human rights and the dignity of the person, deploring violations of religious freedoms. However, most of the 67 addresses given by Pope John Paul II during his visit were directed to Catholics and stressed their responsibilities as believing members of the Church.

The messages were conservative in tone and contained unqualified condemnations of abortion, artificial birth control, homosexual practice, and premarital and extramarital sex. The Pope reminded priests of the permanency of their ordination vows and also ruled out the possibility of ordination for women, bringing protests from a number of misguided Catholic activists.

Little of Pope John Paul’s vision for the Church in the modern world was received with any enthusiasm by the administration and faculty of St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore. It was in the weeks before this momentous visit that all hell broke loose at St. Mary’s. The seminary rector, Father Leonard Foisy, now deceased, was a priest of my diocese and a member of the Congregation of St. Sulpice — aka The Sulpicians — which ran the nation’s oldest seminary since its founding some 200 years earlier.

Just weeks before Pope John Paul’s planned visit, it was somehow learned that all seminarians from several major seminaries in the region were invited by the Holy Father to take part in a Mass for seminarians on the National Mall in Washington, DC. Upwards of a thousand seminarians were to have special seating with an expected crowd of 100,000.

Seminarians at St. Mary’s in Baltimore, one hour from Washington, DC, however, were never told of the invitation, nor were we told that the Seminary Rector had declined it on our behalf for reasons that he refused to divulge. The resultant furor was shocking; not only for the majority liberal seminarians, but for the administration and faculty who just assumed that we would disdain the theology and vision of Pope John Paul II just as much as they did. A line had been crossed that threatened to sever our identity as future priests.

A letter of protest was quickly drafted and signed by more than half of the 160 seminarians representing some forty dioceses across the land. I was one of the signatories of that letter, a fact that the Rector took very personally because we represented the same diocese, the Diocese of Manchester, New Hampshire. As a result, I was labeled a disobedient rebel.

A seminary-wide meeting was held, and the Rector doubled down on his rejection of the papal invitation. He warned that anyone who attempted to attend the Pope’s Mass one hour away in Washington would not receive permission to do so, and would receive failing grades for any course work assigned for that day. He also said that several crucial exams would be held that day and failing grades would be reported back to the diocese of each seminarian along with a report of disobedience to his legitimate authority.

Needless to say, we went anyway. No one has a vocation to the seminary.

The Priest Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest

The graphic above is not a real book, so please don’t try to order it from Amazon. It was created by the BTSW editor in response to a post of mine that stirred an uproar when first posted in November, 2013.

That post publicly refuted another priest who published a letter in Our Sunday Visitor calling for expanded use of the death penalty in the United States. As a prisoner-priest, I wrote in favor of mercy. But it was I, and not he, who kicked the hornet’s nest.

Back to the seminary: One factor that struck me at St. Mary’s in the 1970s was the unwillingness of some bishops to become involved in — or even aware of — the training of their future priests. Formal complaints from seminarians about the blatant disregard for Pope John Paul II by seminary administration were ignored by most of the bishops who received them.

Some of the more traditional seminarians survived only because they were academically brilliant. They became the priests who kicked the hornet’s nest merely for refusing to either bend in their fidelity or be driven out as candidates for priesthood.

In the years since my ordination, I have heard many stories from priests whose priestly spirits were wounded in a kind of spiritual abuse that characterized their seminary years. Perhaps some will comment here.

In January 2023, I wrote and posted “Priests in Crisis: The Catholic University of America Study.” It is a most important document that especially needs the Church’s attention at this time of great transition in Rome. A good deal of pressure had been placed by the pontificate of the late Pope Francis upon those who have come to express their devotion and find spiritual solace in the Traditional Latin Mass. The Catholic University of America Study examines what has been happening in the breech between more liberal bishops and younger more conservative priests. The absolutism of disdain from upper levels for more conservative and traditional expressions of Catholicism has had the effect of driving people toward Tradition, and not from it. In more recent times some bishops have reacted to this by edict and fiat rather than by leadership. One newly appointed bishop in the diocese of Charlotte, North Carolina created a great stir by forcing any observants of the Traditional Latin Mass into the rural hinterlands in his diocese. The previous bishop there had opened a seminary which has attracted a significant number of candidates for priesthood. It remains to be seen what becomes of them, but they should henceforth be treated as a treasure of the Church and not as an experiment. Anything less is to repeat a grave mistake from the 1970s captured in the book, Goodbye, Good Men.

When you think about it rationally, the Traditional Mass, which at one time was the only Mass, seems a very strange place for any bishop to plant his flag on a hill of battle with the People of God. As I pointed out in these pages one week ago, “Jesus Christ is the same, yesterday, today, and forever.” (Hebrews 13:8)

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Sharing this, along with one or two of the timely posts below, just may be a Corporal Work of Mercy for someone else:

Did Leo XIV Bring a Catholic Awakening Or Was It the Other Way Around?

In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men

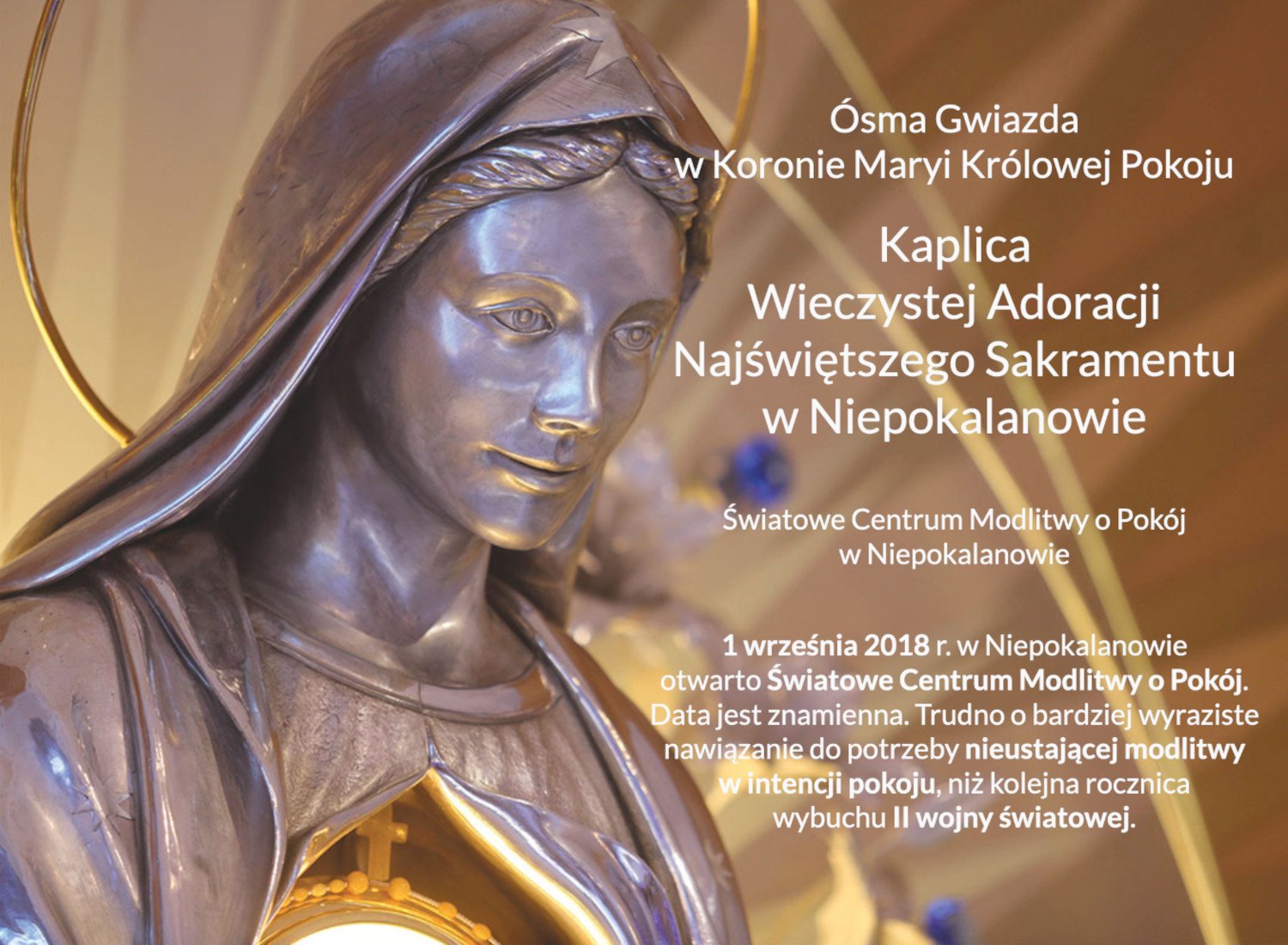

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”