“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Higgs Boson God Particle: All Things Visible and Invisible

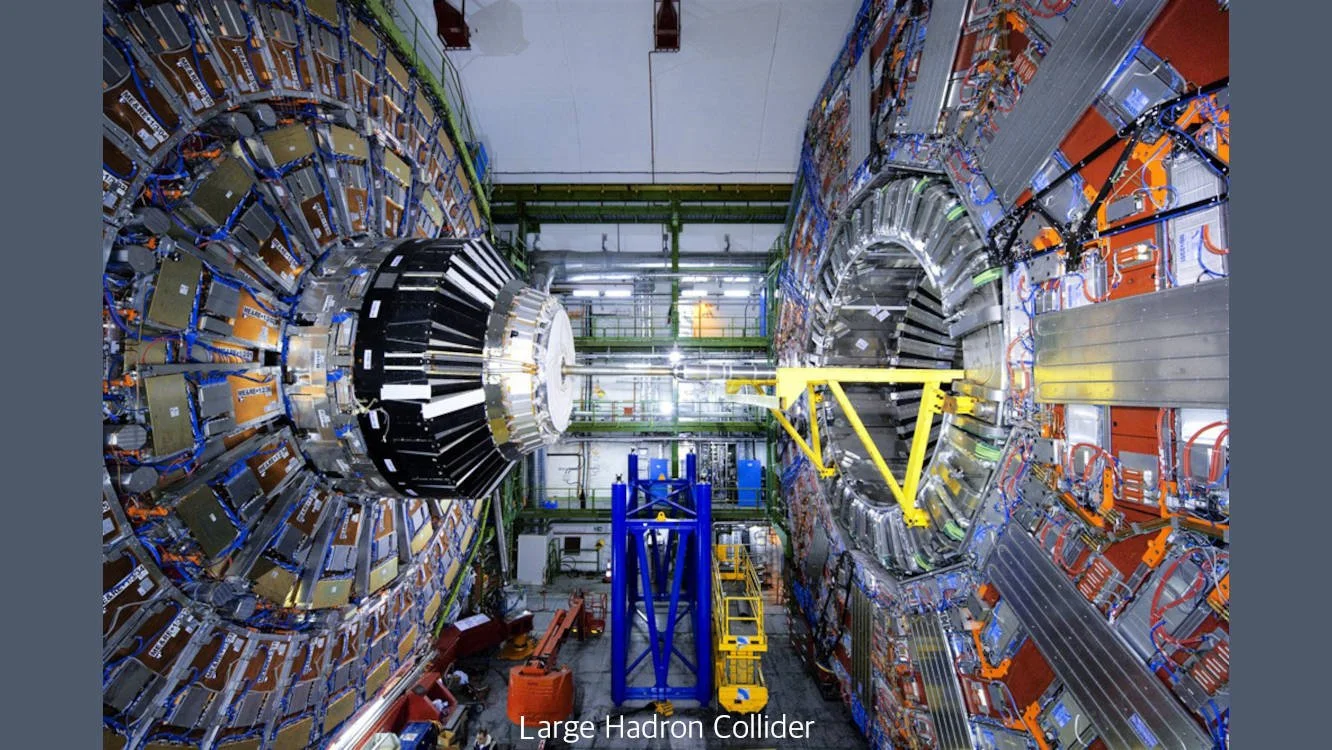

In 2012, scientists at the Large Hadron Collider detected the elusive Higgs boson, a subatomic particle dubbed the “God Particle” explaining the origin of matter.

In 2012, scientists at the Large Hadron Collider detected the elusive Higgs boson, a subatomic particle dubbed the “God Particle” explaining the origin of matter.

February 4, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

“Two Higgs boson particles walked into a bar. Over drinks one said, ‘I hear Stephen Hawking bet $100 that we don’t exist. What if he’s right?’ The other replied, ‘No matter!’ ”

Get it? No matter? Get it? Well, hopefully you will in a few minutes. I didn’t get it either until I did some heavy-duty reading.

If this post is creating a touch of déjà vu, a sense that you have seen it before, it’s because you probably have. Something quite unusual happened here at this blog in recent weeks. In the earliest days of this blog in 2010, I was contacted by a reader in Australia about a new book by physicists Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow entitled The Grand Design (Bantam Books, 2010). The letter writer was concerned that media outlets in Australia and around the world were citing aspects of the book out of context in an attempt to demonstrate that Stephen Hawking declared that God does not exist. That was a faulty interpretation and the reader wanted me to set the record straight. It was a tall order, but I had time on my side to ponder and present a contrary point of view. So on October 6, 2010, we published “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?”

A lot of work went into that post, but to my chagrin it was met by most of our readers with a yawn the size of a giant black hole. Fifteen years later, someone (not me) submitted that post to an advanced artificial intelligence model requesting an analysis of it. The results were then read to me by our Editor. AI scoured the Internet and then referred to me as “a Catholic priest with a background in science” while singling out that post as “a significant example of bridging the gap between science and faith.”

So of course, I thought that was the nicest thing any AI had ever said about me (There was very little to compare it to.). Given this new interest in a bridge between science and faith, I decided to haul out this 15-year-old post and rehabilitate it for a new audience. On July 30, 2025, we republished “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” The result was mind boggling, but it was not immediate. A few months later that post started showing up in our stats and then it began a viral spread. By January it was outpacing my regular weekly posts in popularity. And then by mid-January it spread all over the world in unprecedented numbers for this blog.

I cannot pretend to know why this happened. I do not understand the global attention to this one post on the space-time continuum. Perhaps my only conclusion is that when I post a bomb, just wait 15 years and post it again.

The Discovery

There is another post of mine that also bridges the gap between science and faith. I do not have an explanation for why or how, but another of my posts, this one from 2012, also began to show up in unusually large numbers with that other post. I have long wanted to repost this one with some updated information so that those who are currently reading and spreading it can see the updated version. It is “The Higgs Boson God Particle: All Things Visible and Invisible.”

I first wrote it in September 2012. It, too, was met with a rather extended yawn, but today it shows up often and everywhere. It profiles the work of the late physicist Peter Higgs who rose to prominence in the scientific community in 1964 when he theorized that the Higgs boson exists as a necessary subatomic particle which explains the existence of matter. After my post was first published, the Higgs boson was experimentally demonstrated again and Peter Higgs was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. He died on April 8, 2024 at the age of 94 knowing that his life’s work was a major addition to the scientific understanding of the Universe.

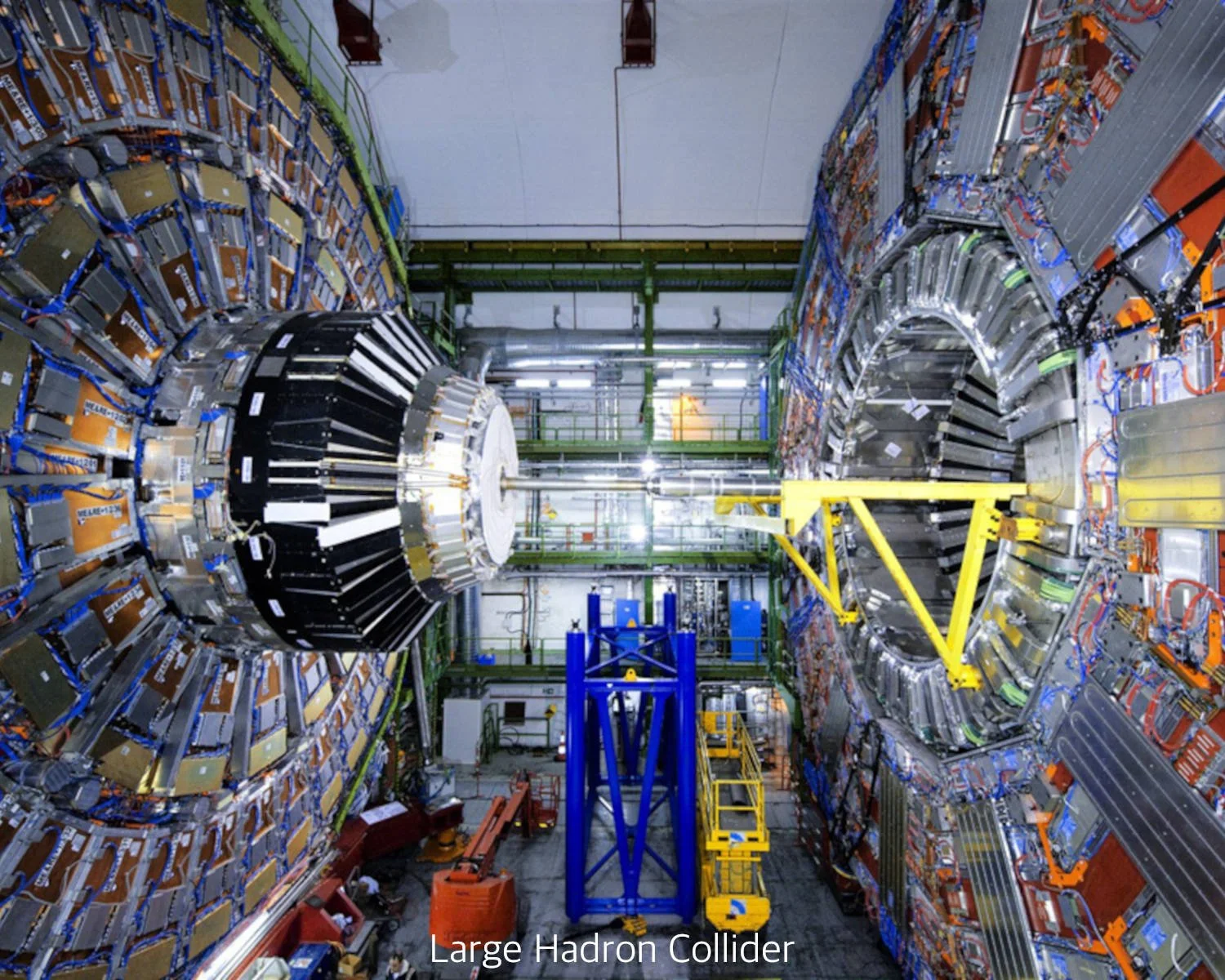

A boson in physics is a component of subatomic particles such as protons and photons, which exist in every atom of matter. As a class of particle, a boson is so-called in honor of Indian physicist, Satyenda Nath Bose, who collaborated with Albert Einstein. The existence of a then-theoretical Higgs boson resolved a puzzle in the Standard Model of physics, a widely accepted model for how particles interact. The thinking in the Standard Model was that particles such as photons — particles of light — have no mass. They should move throughout the Universe unhindered. The mathematics of the Standard Model explained successfully the existence of particles, but not mass or matter. The Higgs boson proposed by Peter Higgs in 1964 was an explanation for how particles could attain mass, and thus bring into being a Universe filled with matter that we can see or otherwise detect.

CERN, the European agency for nuclear research, operates and oversees the Large Hadron Collider. It is a donut-shaped laboratory 27-miles in circumference on the French-Swiss border. Two beams of protons were set on a collision course moving at close to the speed of light. Their collision resulted in an explosion that recreated the conditions of The Big Bang, the scientifically accepted origin of our Universe. During the collision, a supercomputer detected the presence of the Higgs boson particle and a Higgs field for a trillionth of a second. It was the first time its existence had ever been established in a laboratory

On July fourth in 2012, physicists announced that they had a momentary glimpse of the elusive Higgs boson, the subatomic particle long theorized to exist, and without which matter itself would not exist. The physicists who reported that they only found “evidence” of the Higgs boson were just being careful scientists. The discovery had a 99.9999% rate of certainty. There is no doubt left. The Higgs boson does indeed exist and that experiment has since been ratified.

So what exactly does this mean? Many scientists grimaced every time someone in the news media referred to this discovery as “the God particle.” Using science out of context to debunk religious faith is a favorite pastime of some in the media, but the reverse should also not happen.

I took a hard look at the interaction between faith and science in “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” After publication of The Grand Design, some in the news media speculated that Hawking’s book demonstrated that gravity — and not God — is responsible for the creation of the Universe. My conclusion was simply that Stephen Hawking has thrown in with the wrong “G,” and the pundits misreading his book have confused the tools of God with God. I cited in that post a vivid example. If you were an archeologist digging in ruins in Florence, Italy and you discovered a worn chisel that was used by Michelangelo to create the Pietà, one of the most celebrated examples of sculptured marble in art history, would you then conclude that Michelangelo did not create the Pietà, his chisel did?

What I find most interesting about the recent discovery is that the Higgs boson appears nowhere in Stephen Hawking’s The Grand Design. His analysis of the science of cosmology omitted it entirely. In fact, two decades ago Stephen Hawking wagered $100 that the Higgs boson would never be detected. He lost the bet.

The discovery of the Higgs boson is a big deal in science because it presents a purely scientific explanation for how matter exists, but not why. The model for creation it implies is that a primordial atom exploded in what we call The Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago. As the explosion cooled, a force known as a “Higgs field” — which contained the Higgs boson — was formed and permeates the Universe. As other particles interacted with this field, they acquired mass allowing gravity to bring particles together. It acted sort of like a dam slowing particles so that they would mass together. The result was matter as we know and see it — everything from stars to us. It’s sort of the yeast with which God bakes bread.

A Day Without Yesterday

The Higgs boson was detected by the Large Hadron Collider’s super computers in July 2012 for a fraction of a trillionth of a second. The tiny collision sent particles in every direction producing the energy equivalent to 14 trillion electron volts and blistering temperatures. The collision recreated a tiny model of the instance of The Big Bang. Some theorize that it was the presence of the Higgs boson particle within the primordial atom that caused The Big Bang itself, and the explosion of all matter in the Universe.

I find this all fascinating, but what is most fascinating is that the entire model was first mathematically predicted, and then demonstrated to even Albert Einstein’s satisfaction, by a Catholic priest. I wrote of the Belgian priest and physicist, Father Georges Lemaitre, in “A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and the Big Bang. As a result of that post and others related to it, I began a correspondence with Father Andrew Pinsent, who prior to priesthood had been a physicist at CERN. We collaborated on a very special post, “Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang.”

If ever you bristle about the typical anti-Catholic mythology that religion attempts to hold back science, remember that the originator of all the science behind this model of creation was a Catholic priest, and many of the great scientists of his time did everything they could to suppress his ideas. They failed because they could not successfully refute either his faith or his science. In the end, even Einstein bowed to Father Lemaitre, declaring that his model was “the most satisfactory explanation of creation I have ever heard.”

Pope Pius XII applauded Father Lemaitre’s discovery of The Big Bang because it challenged the acceptable science of the time which claimed that the Universe was not created, but always existed and is eternal. Einstein later acknowledged that his “Cosmological Constant” was his greatest error.

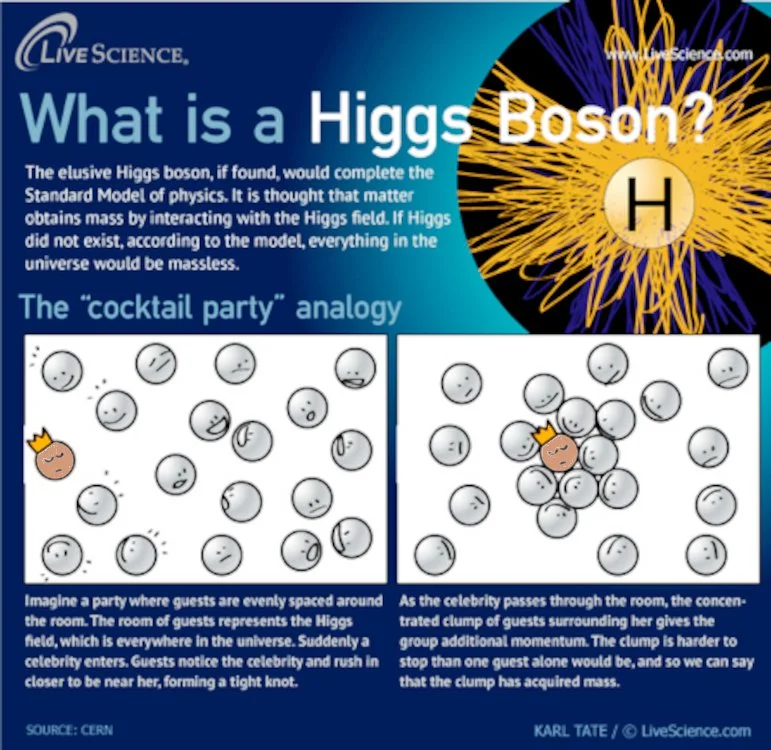

Perhaps the greatest miracle of all for me was receiving the photo below of Pornchai Moontri’s Godfather, the late Pierre Matthews, whose mother was a close friend of Father Lemaitre, who became Pierre’s Godfather. The odds that my roommate in Concord, New Hampshire would turn out to be the Godson of a man whose own Godfather discovered the Big Bang are as great as the odds of the Big Bang itself.

Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at City University of New York, wrote a brilliant and (unlike this post) brief commentary about the Higgs boson for The Wall Street Journal (“The Spark That Caused the Big Bang,” July 6, 2012). Professor Kaku wrote:

“The press has dubbed the Higgs boson the ‘God particle,’ a nickname that makes many physicists cringe. But there is some logic to it. According to the Bible, God set the Universe in motion as He proclaimed ‘Let there be light.’”

“So why did the Higgs boson particles hurry to church?

Because Mass could not start without them.”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: For open minds and enlightened souls bridges are taking shape between the realms of science and faith. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?

Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang (a must-read by Father Andrew Pinsent)

The James Webb Space Telescope and an Encore from Hubble

For Those Who Look at the Stars and See Only Stars

+ + +

And then there was this: xAI Grok on Higgs Boson, God Particle, Science and Faith.

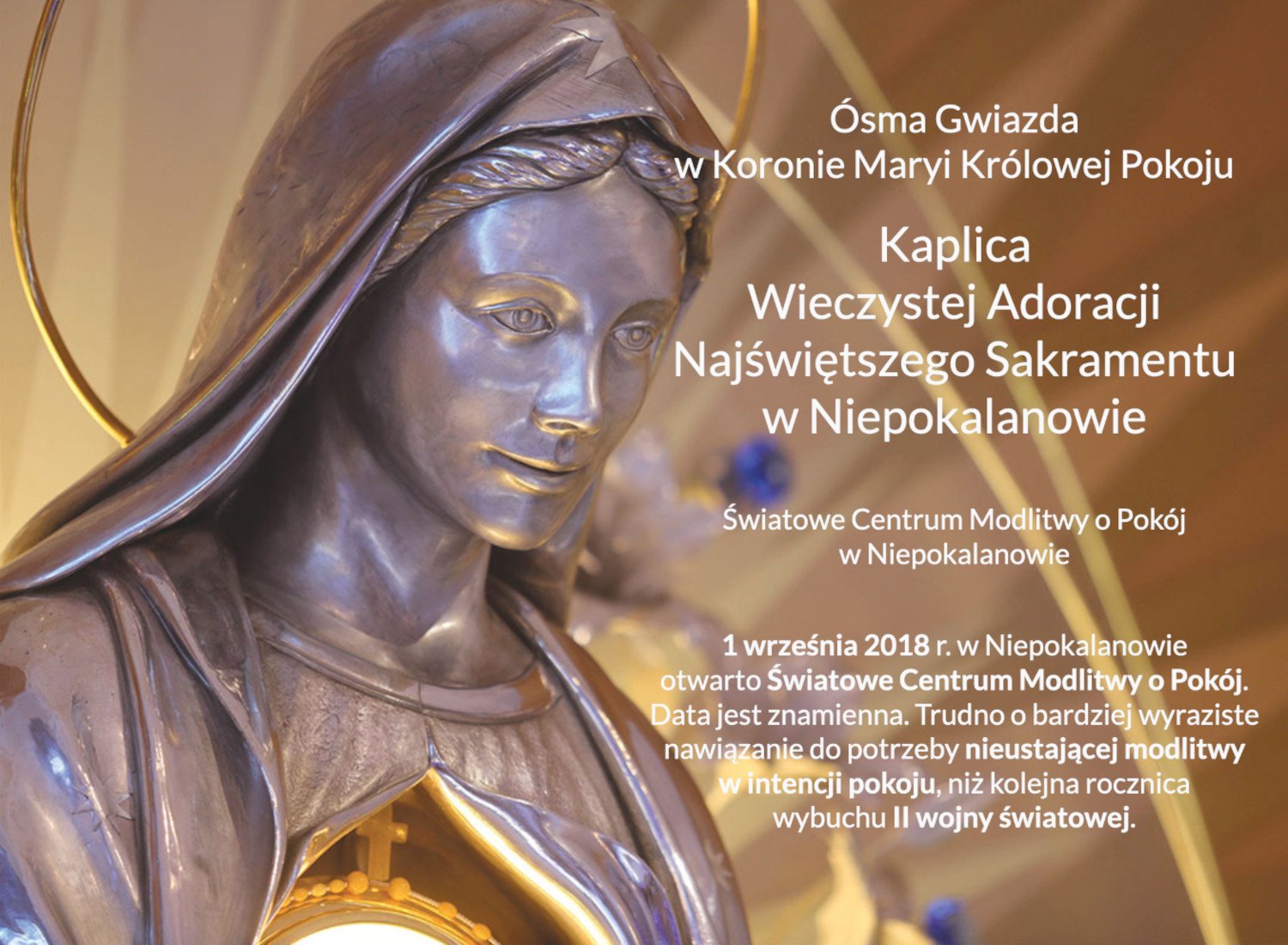

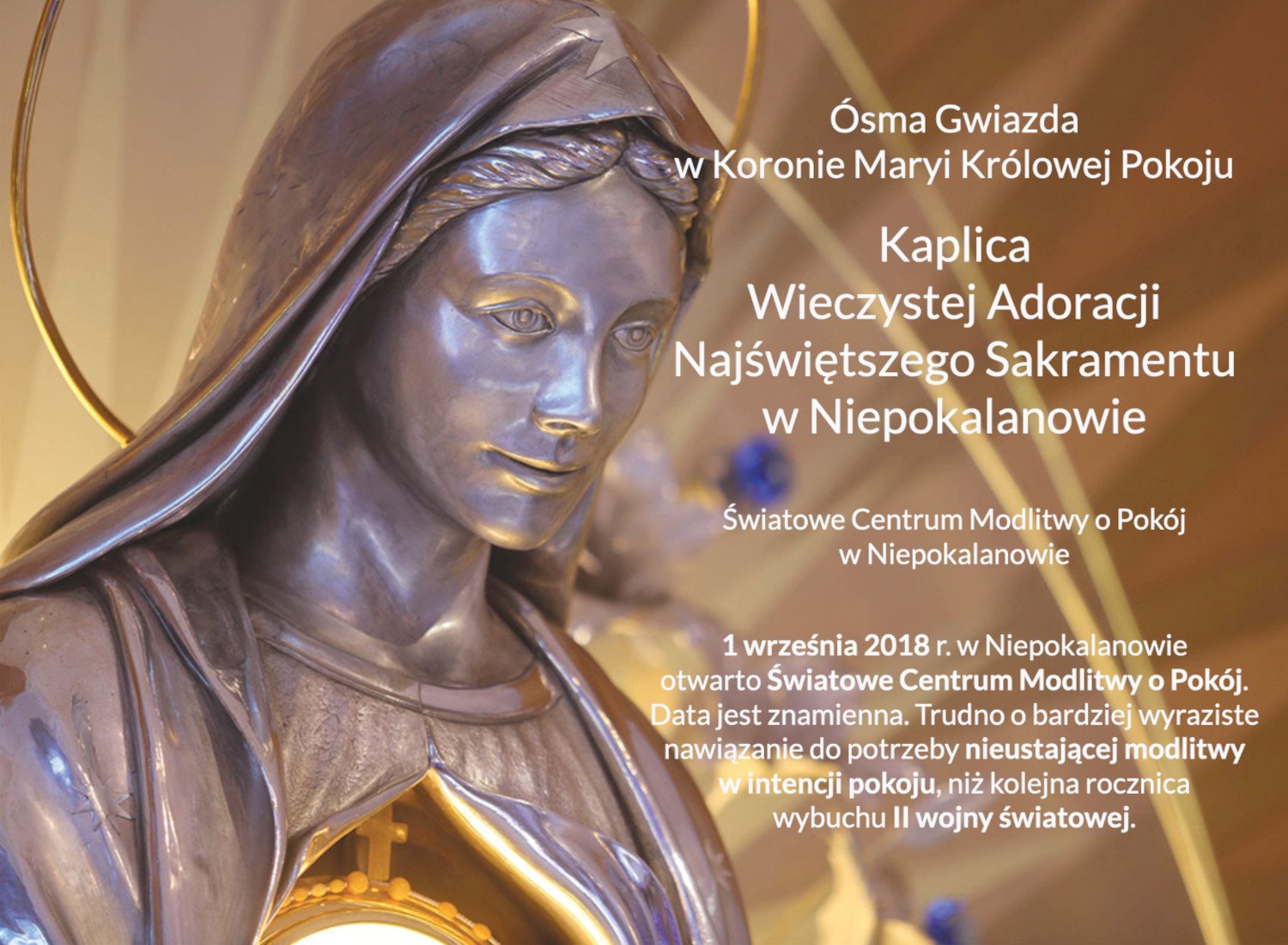

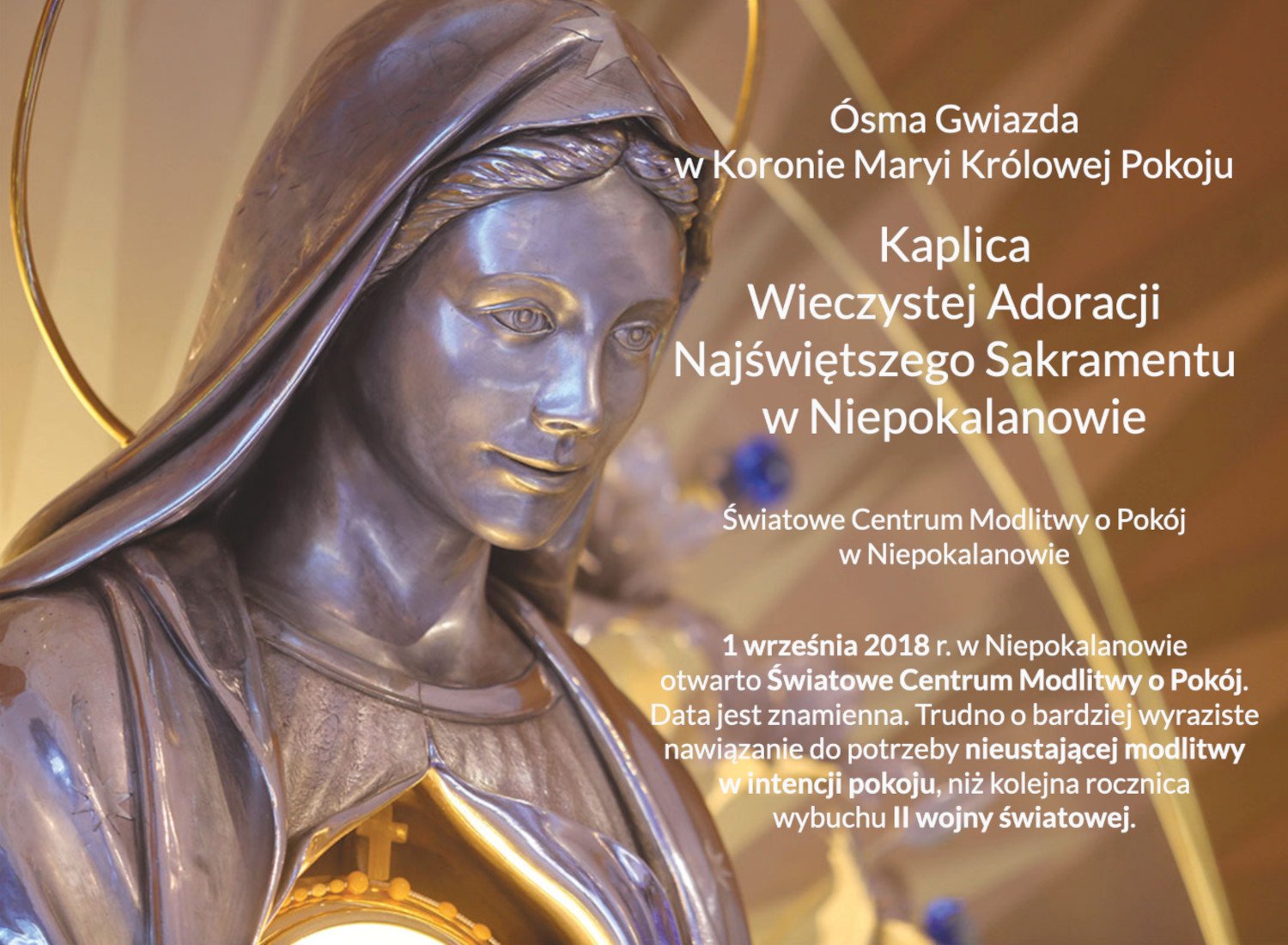

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?

Physicist, Stephen Hawking, died on March 14, 2018. His book, The Grand Design, caused many to believe that he widened the chasm between science and faith.

Physicist, Stephen Hawking, died on March 14, 2018. His book, The Grand Design, caused many to believe that he widened the chasm between science and faith.

July 30, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

Back in 2010, in the earliest days of this blog, I wrote a post about the late, great physicist, Stephen Hawking. It was among my first posts about the dichotomy between science and faith. A controversial book, The Grand Design, published not long before I wrote about Professor Hawking, caused many to believe that he was an atheist who concluded that there is no reason to believe that God created the Universe or anything else. He attributed all of creation to one overpowering force, gravity. At the time I was pondering a response, I imagined that if I had been on an archeological dig among 15th Century ruins in Rome and found a worn chisel that was known to have belonged to Michelangelo, and used to create the Pieta, what sort of controversy would that entail? Would naysayers suggest that Michelangelo did not thus create the Pieta, his chisel did. That is the simplest response to anyone who used gravity to demonstrate that Stephen Hawking did not believe in God. God created not only the material Universe, but also all the material tools that brought the Universe into being.

Also a few weeks before I first wrote about Hawking, Pope Benedict XVI beatified John Henry Cardinal Newman in Birmingham, England. The Holy Father emphasized Cardinal Newman’s “insights into the relationship between faith and reason,” and commended him for applying “his pen to many of the most pressing subjects of the day.” Without doubt, Cardinal Newman also might have had a pointed response to the media tremors after physicist and author, Stephen Hawking declared that science can explain the creation of the Universe without God.

I mentioned Stephen Hawking in another 2010 post, “A Day Without Yesterday: Father Georges Lemaitre, and The Big Bang.” His declaration about creation came in The Grand Design. Many in the media called it a definitive statement about the existence of God. It was no such thing, but the news media cannot be accused of a lack of trying to diminish the faith of billions.

I cannot claim to have even a fraction of the gifts of faith and reason that Saint John Henry Newman would call upon to respond, but as a priest who respects science, I feel driven to weigh in. First, I have to confess that I had not by then read The Grand Design, but I eventually did. However, in a full-page article in The Wall Street Journal in 2010, Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow laid out the cosmology behind the book and their conclusions (“Why God Did Not Create the Universe,” September 4-5, 2010).

It is to that article that I here respond. If you have a concern for the implications of Professor Hawking’s pronouncement that God had nothing to do with bringing you and your world into being, please read on. There is a lot at stake here. I will address this from two points of view.

My Response as a Priest

Like Father Georges Lemaitre and Saint John Henry Newman, my response is first and foremost that of a Catholic priest. I have known many priests who have struggled with faith and some who have lost their faith. I correspond regularly with a priest who lost his faith years ago. Now this declaration by Stephen Hawking feels like a nail in faith’s coffin for him. I have lived 72 years of struggle over the question of God. I have arrived — in spite of toil, trial and tribulation, and more than my share of each — at what I think is a more than tepid faith in God’s existence and in His Grand Design. I believe in His creation of our existence. I believe in His enduring and caring Presence in this life and the promised life to come. I believe that our relationship with Him can survive this life if we walk the path He has shown to us. I wrote about that path in a recent post, “What Shall I Do to Inherit Eternal Life?”

I have read nothing in any of Stephen Hawking’s writings that causes me to wonder whether my faith conclusions are valid. I write as a priest and believer. My faith and my priesthood both came into being in a time of great social upheaval. The existential philosopher, Frederick Nietzsche (1844-1900) seemed to rule the reasoning — or lack thereof — of the 1960s. His contempt for Judaism and Christianity, and his cynical view that mankind is but a herd at the mercy of the ruling and gifted intellectual elite, marked the dawn of the “God is Dead” movement. The bumper stickers were everywhere:

“GOD IS DEAD!” Nietzsche

In the 1970s, that sorry and narcissistic wave began to dissipate, but not before destroying the faith of many who bought into it. I remember buying a bumper sticker for my seminary room door in 1978:

“NIETZSCHE IS DEAD!” God

The three masters of deceit — Freud, Marx, and Nietzsche — are all dead and not only their persons but their ideologies as well. Each reduced man to his basest, soul-less drives, and each in his own way was an enemy of faith. I do not count Stephen Hawking among them. Contrary to what the news media was lifting out of his latest book — and out of context — Stephen Hawking did not denounce God, nor does he claim to have proven that God does not exist. The exact quote that so many in the media now read into from his WSJ article cited above, and from his book is this:

“The discovery recently of extreme fine-tuning of so many laws of nature could lead some back to the idea that the grand design is the work of some grand Designer. Yet the latest advances in cosmology explain why the laws of the universe seem tailor-made for humans, without the need for a benevolent creator.”

But who would then explain the identity of the Tailor? This comes as no great revelation. One might expect that I, as a priest, would proclaim that the Universe was brought into being and maintained, at least in part for our benefit, by a Divine Creator whose title is also His name: God. But did anyone really expect Stephen Hawking, or any cosmologist to make the same declaration? What Professor Hawking has written is neither new nor surprising in cosmology. I do not, and will never have a faith that depends on science to finally and definitively weigh in on God’s existence and creation of the Universe. Science should never be able to do this to the satisfaction of any person of faith. To say that science can explain creation without God is not to say that God did not create everything — including the science and scientists trying to nudge Him from center stage. Faith is far more than the dictates of reason and the pronouncements of science. Our tradition of faith does not reduce God to His quantum mechanics, and does not promise to teach all there is to know about the created Universe or the laws of physics.

Our faith promises that we can know God through Christ in a personal relationship without fully explaining God. Who in this world can claim to fully comprehend God? Certainly not I. Faith is not an event, and science does not make or break it. Faith is a pilgrimage, and like any pilgrimage, most of us will have times of wandering, and wondering whether we will ever arrive, whether we will ever get to the point at which there are no doubts. That is the point of faith. It is its own evidence.

“Faith is the assurance of things hoped for; the conviction of things unseen”

— Hebrews 11:1

Faith at some point involves an assent of the intellect (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 155) to the revealed truth about God Himself. Central to that truth is the redemption offered to us through Christ who not only reveals God to man, but “fully reveals man to himself” (Gaudium et Spes, 22). None of us looks to Stephen Hawking, or to science, to reveal the truth about God. Faith in God and His creation can no more be subjected to the scientific method than science can legitimately be subjected and defined in the light of faith. Who among us, when faced with life’s inevitable crises, ever cried out to Stephen Hawking for mercy or for redemption?

The greatest physicist of the 20th Century, Albert Einstein, never pondered God until his discussions with fellow physicist Father Georges Lemaitre. When those discussions proved to Einstein that the Universe came into being at a specific point some 13.2 Billion years earlier, Einstein responded, “I want to know God’s thoughts. The rest are just details.”

My Response as a Student of Science

I write secondly with a lifelong respect for science as a tool, not for understanding God, but for understanding the mechanics of the Universe in which we exist. This has been not so much a journey of the mind, but of the heart and soul. I at one time thought quantum mechanics referred to guys who worked on Volkswagen Beetles. To my great fortune, my mind has expanded a bit since then.

I have several times written of one of my heroes on the parallel journeys of both science and faith. One of these posts, “A Day Without Yesterday” is the story of priest, mathematician and physicist, Father Georges Lemaitre, the originator of the Big Bang explanation of cosmology and the man who changed the mind of Albert Einstein on the origin of this created Universe.

A French publication, Les Dossiers De La Recherche (No. 35, May 2009) had an interesting article entitled “Le Big Bang Histoire: De La Science A La Religion” (“The History of the Big Bang: From Science to Religion”). I am grateful to my Belgian friend, Pierre Matthews (who is also the Godfather of Pornchai Moontri). Pierre and his family knew Father Georges Lemaitre well and they translated into English this portion of the article cited above in French:

“Pope Pius XII, an enthusiastic amateur astronomer, addressed the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1951. His talk dealt with recent findings in cosmology stating: ‘It appears truly that today’s science going back millions of centuries has succeeded to witness the initial ‘fiat lux’ [Let there be light], coming out of nothing, that very moment of matter and ocean of light and rays, while the chemical components of particles split and assembled into millions of galaxies.’

“Pope Pius XII referred openly to Fr. Georges Lemaitre’s scenario. But this ‘concordism’ assumed to exist between revealed truth and science is counter-publicity for those, among them Fr. Georges Lemaitre, wanting a total and independent separation of the history of the Universe, evolution, and religious truth.

“Following a meeting with Fr. Lemaitre, Pope Pius XII a year later rejected, before the General Council of the International Astronomical Federation, any concordance between the two fields: science and faith. For Father Lemaitre, this was a double victory: cosmology can develop in total freedom and religion should no longer fear contrary positions based on new scientific discoveries.”

Why was Father Georges Lemaitre so insistent that the Pope should declare no concordance between faith and science? The obvious reason is that, for Father Lemaitre — a man of deep faith and a brilliant physicist and cosmologist — faith and science are parallel fields and should never limit each other. The Church suffered a black eye for its condemnation of Galileo’s views about science four centuries ago, but science has often seemed utterly ridiculous for holding the Church in contempt for not responding to science in 1660 as it would in 2025.

In 2005, noted science writer, Chet Raymo wrote a blog post entitled “The Future of Catholicism” on his Science Musings blog (April 10, 2005). Raymo wrote:

“In spite of the pope’s outreach to the scientific community, the Church has been slow to understand the theological implications of the scientific world view. The Church’s truce with modern cosmology and biology is uneasy at best, although certainly more enlightened than the outright rejection by fundamentalist faiths.”

Chet Raymo was right, but in a limited way. He very much understated the appreciation for scientific achievement demonstrated by the Church in the last century. We can expect this to improve greatly during the pontificate of Pope Leo XIV whose own education includes a degree in Mathematics, which leaves him well disposed to the work of Fr. George Lemaitre.

I had a brief discussion about this some years ago with a fundamentalist Evangelical pastor I know. He is an educated man, a university graduate, and well read but only very narrowly so. I asked for his opinion of what I have written above about Stephen Hawking’s views.

His response came as no surprise, and it was little different from what we might have heard from one of the Calvinist Puritan founders of New England in 1620. His view was an utter rejection of science. “The Universe was created by God in six days about 6,000 years ago. There is no such thing as poetic and metaphorical language in Scripture.” I asked him how he would explain the discoveries of bones that are many tens of millions of years old, or the fact that we can see galaxies that are millions of light years away. His answer was to simply ignore the questions. Of course, this man also believes that the Catholic Church is the anti-Christ, the “Whore of Babylon.” He believes it is not only science that is condemned, but the Catholic Church as well, and he would cite the Church’s nod to science as evidence for that view.

Science is the empirical examination of the physical Universe. Gone are the dark days in which science and religious dogma demanded conformity one with the other. There are legitimate forums for dialogue, however. It is more than ironic that Stephen Hawking was a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Science. There were calls for him to resign after he wrote The Grand Design, but I believed then that he should retain his position. Dialog should not require conformity, and the Church should not be daunted by diverse scientific views.

Using Father Georges Lemaitre’s model, Stephen Hawking should no more publicly weigh the legitimacy of Judeo-Christian belief in Creation as a design plan of God than the Pope should affirm or deny black holes. My concern for the controversy surrounding Stephen Hawking’s 2010 book is not that it encourages masses of believers to set aside their Catholic faith, as Chet Raymo declared to have done, but that it may have the effect of encouraging some Christians, Catholics among them, to set aside science. Either approach would be tragic.

Professor Hawking’s foray into the realm of faith does not change the way I perceive God. The very fact that I perceive God at all is its own evidence, “the conviction of things unseen,” (Hebrews 11:1). What it does change is my respect for the strides taken by science to speak also to the masses of people who are not scientists, but are people of faith open to science. There is a danger that science is gradually placing itself outside the experience of the great majority of people while claiming to enlighten its own elite. In this, there is a growing rift between science and the reality experienced by billions of people of faith.

The late Stephen Hawking’s view was in danger of sparking a return to the bad old days of Nietzsche, this time by the establishment of the “uber-scientist” for whom masses of faithful believers are but an ignorant herd. It is science, and not faith, that faces the greatest harm. Stephen Hawking presented that the laws of gravity, and not God, created the Universe we live in. I am not prepared to rewrite Scripture. It is not the experience of thousands of years of belief that “In the beginning, Gravity created the heavens and the earth.”

I have a response as a prisoner, too. I certainly believe in gravity, but there’s precious little solace in it, and it speaks nothing to the reality of my soul. Sorry, Professor. I respect your cosmology greatly, but I think you should not have thrown in with the wrong “G!”

I still like you, though, and I believe God does, too. He has inspired me to pray for you.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Sharing is important to place these pages before believers who may benefit from them. For 15 years we shared posts at various Catholic groups on Facebook. A few months ago Facebook called my posts “spam” and froze our account. I can no longer share there, but you can, and I thank you if you do so.

You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

“A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and The Big Bang

Science and Faith and the Big Bang Theory of Creation

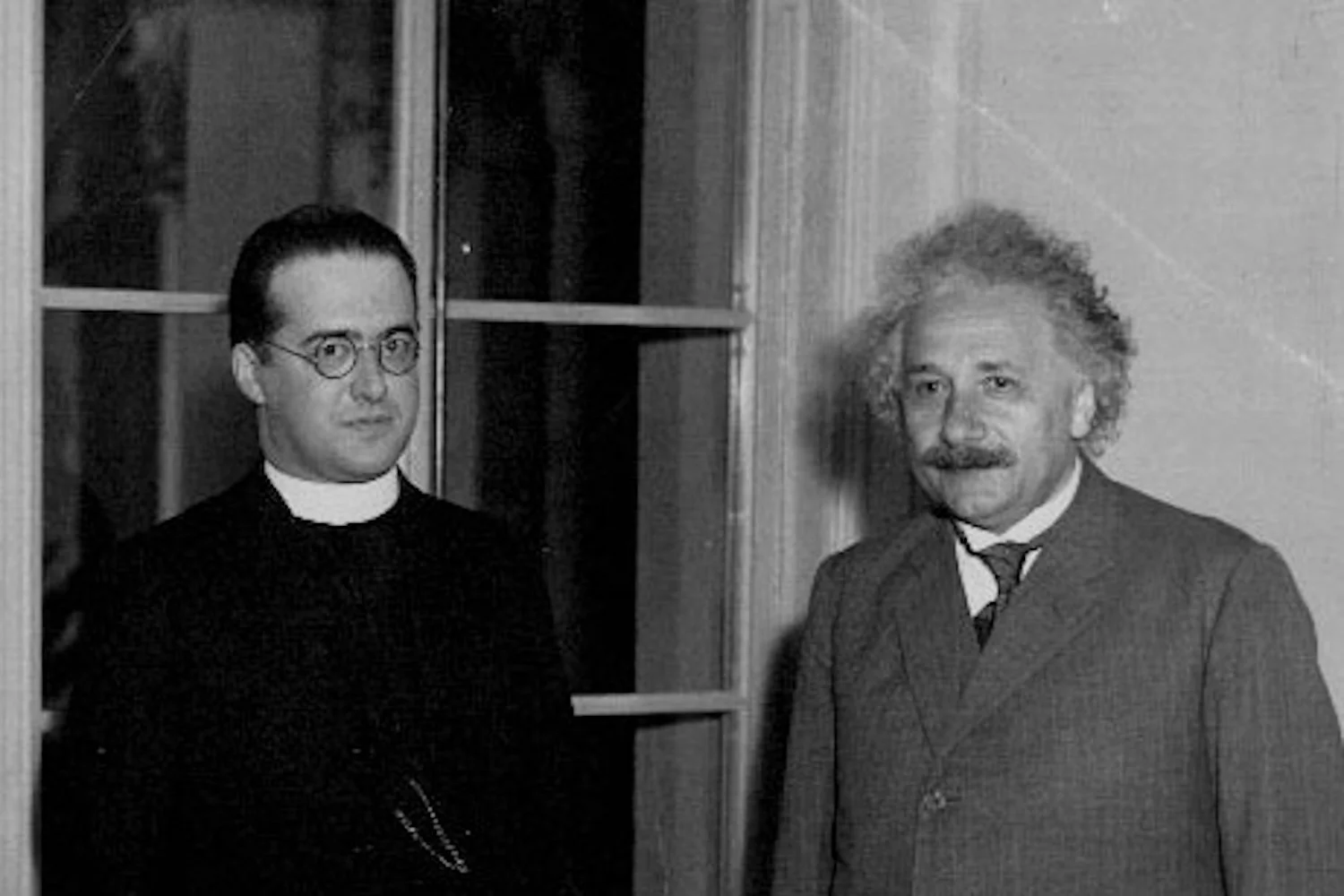

Albert Einstein and Fr. George Lemaitre at the California Institute of Technology in 1930.

"I want to know God' thoughts. The rest are just details." -- Albert Einstein

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Science and Faith and the Big Bang Theory of Creation

The discovery of cosmic ripples from the birth of the Universe is evidence beyond reasonable doubt of the Big Bang theory first proposed by Fr Georges Lemaitre.

The discovery of cosmic ripples from the birth of the Universe is evidence beyond reasonable doubt of the Big Bang theory first proposed by Fr Georges Lemaitre (pictured above with Albert Einstein and Fr Andrew Pinsent)

June 18, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light.”

— Genesis 1:1-3

When my friend Augie was back in 2014, he used to like to stop by my room to compare notes about our favorite TV shows. We had been mesmerized by the return of Jack Bauer’s 24 back then, and we were eagerly awaiting the extra-terrestrial return of Falling Skies. One day when Augie came by my door he asked, “What do you think of The Big Bang Theory? “ I was so glad he asked. I launched into a 15-minute analysis of the science of modern cosmology and the meaning of the so-called Big Bang for both science and faith. When I finished, Augie looked dazed and said, “Umm…I meant the TV show!”

Then Mike Ciresi (“Coming Home to the Catholic Faith I Left Behind”) stopped by and asked, “What are you writing about this week?” “The Big Bang Theory,” I replied, hoping for another chance to spout off my explanation of the Cosmos. “Oh, I LOVE that show,” said Mike as he made a hasty retreat.

Okay, what had I been missing? Despite its being the most watched show on television, I had never seen an episode of the CBS hit, “The Big Bang Theory.” So I watched a few reruns. The show turned all social science on its head. I had no idea nerds were now “in!” And they even had girlfriends! Nerdhood had sure changed since I studied physics!

Alas, however, it was the OTHER Big Bang theory that I am taking on this week, but I implore you not to click me away just yet. I MUST write about this, and I hope you will read on. I am not quite as funny as Sheldon, Leonard, Howard and Raj, and of course Penny! I can only be that funny when I’m trying hard NOT to be funny! Like now!

I must write about the Big Bang theory for two reasons. First and foremost, a new discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation was big news a few years ago because it lent evidence beyond reasonable doubt to the truth of the science behind the Big Bang, a discovery first proposed by a Catholic priest who turned Twentieth Century cosmology on its head. I want to write about what this means for both the science of cosmology and the faith that we have all invested into a notion that this Universe was created by God. I will get back to that.

Finally, I must write about this because I was somehow thrown into the ring of debate about what it all means. My name showed up on a Facebook page for a quantum physics website. Mary Anne O’Hare posted in response to an article about the implications of so-called parallel universes and the “Many Worlds” theory:

“Gordon J. MacRae is one of the best authors who melds science with faith. Would be interested in his feedback.”

Thank you, Mary…I think! However, the ego bubble you built was burst just moments after I read your remark. BTSW reader Liz McKernan from England sent me a clipping from the (UK) Catholic Herald. It reminded me that my paranormal quest for science and truth beyond these stone walls is dwarfed by another priest, the U.K.’s Father Andrew Pinsent. He is one of the most accurate and prolific contemporary writers and bridge builders in the realm of science and faith. Liz McKernan’s clipping detailed Father Pinsent’s presentation to a packed room at the Newman Forum on “The Alleged Conflict Between Faith and Science.”

Are Science and Faith Mutually Exclusive?

When I decided to profile the work of Father Andrew Pinsent, I was surprised to learn (Ahem! Ahem!) that he also happens to be a reader of Beyond These Stone Walls. You also may recall a previous post of mine that revealed a connection between Father Georges Lemaitre and our friend, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri whose Belgian Godfather, Pierre Matthews, was a close family friend of Father Lemaitre. The photo above depicts Pierre Matthews and Fr. Lemaitre together during a family vacation. It came as a great shock to me to learn that Pornchai, my roommate of the previous 15 years, is probably the only person on Earth who can say that his Godfather’s Godfather is the Father of the Big Bang and Modern Cosmology.

Before I delve further into Father Andrew Pinsent’s defense of the truth about Catholic contributions to science, however, I want to comment on another television show I awaited with great anticipation. The FOX -TV production of Cosmos hosted by astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson is terrific despite one very unfortunate and inaccurate anti-Catholic slur in its first segment: “The Roman Catholic Church maintained a system of courts known as the Inquisition and its sole purpose was to torment anyone who dared voice views that differed from theirs.”

It seems the Cosmos writers have been reading far too much of the sort of shoddy revisionist history put forth by novelists like Dan Brown. As the University of Dayton historian, Thomas Madden, pointed out, the Inquisition formed at a time when much of European society was in a perilous state of disorder, and the order it brought to anarchy saved thousands of lives. More importantly, Professor Madden wrote, “The Catholic Church as an institution had almost nothing to do with” the Inquisition.

The insinuation by a Cosmos background writer was that the Catholic Church has been hostile to science. However, the truth about the relationship between science and faith in the Twentieth Century demonstrates that just the reverse has more often been the case. For much of the later Twentieth Century, a fringe but vocally dominant number of scientists have been far more hostile to religion than religion has been to science. Few living scientists have done more than Father Andrew Pinsent to refute the attempts of this anti-religion fringe to replace faith in God with faith in science by always pointing to the “irrationality of believers.”

Father Pinsent, a doctoral-level physicist with a doctorate in Philosophy, has helped redeem science by exposing the truth about the great contributions to science by Catholic priests. His examples include the Jesuit astrophysicist, Fr Angelo Secchi; the father of the science of genetics, Msgr Gregor Mendel; and of course the astronomer and mathematician, Fr Georges Lemaitre. In this list, I cannot exclude Father Andrew Pinsent himself who after a career at the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion at Oxford is currently professor of Philosophy at one of the most prestigious Catholic seminaries in the United States, Mount St. Mary’s Seminary, also known as the Athenaeum.

Science from East of Eden

Still, I greatly respect and admire Neil deGrasse Tyson who went on in Cosmos to repair the damage somewhat by giving Fr Georges Lemaitre due credit as a foundational theorist of modern physics and cosmology right along with Albert Einstein.

The description of Father Lemaitre’s discovery as “The Big Bang” actually began as a term of mockery of his idea. The term first appeared in 1949, more than two decades after Lemaitre first proposed his theory. The prevailing winds of scientific thought for much of the first half of the Twentieth Century had settled on a belief that the Universe was not “created” at all, but had always existed, had no beginning, and will have no end. In that sense, for science, the Universe itself replaced God as eternal and without an origin. This was the accepted view, even by Einstein.

It was this predominant view that relegated the Judeo-Christian understanding of Creation to the shelf, treating it, and all religion, as a quaint anachronism stubbornly clinging to bygone days of scientific ignorance. Science attempted to remove all rational belief from our Biblical Creation account, and declared it to be a myth in the way we popularly understand myth. In mid-Twentieth Century science, God was obsolete, and some in philosophy were soon to follow with “God is dead!” Many in science held that if science could so undermine the very first awareness of man that God is Creator, all the rest of Judeo-Christian faith would eventually crumble.

Then, in the 1920s and 1930s, along came a brilliant mathematician-priest who subjected the conclusions of science to the rigors of mathematics. I wrote about the challenge this priest posed to the prevailing winds of science in “A Day Without Yesterday: Father Georges Lemaitre and the Big Bang.” Father Lemaitre was much respected by Albert Einstein, but far more for his mind than for his faith. At a 1933 conference in Brussels exposing his Theory of General Relativity, Einstein was asked if he believed it was understood at all by most of the scientists present. Einstein replied, “By Professor D. perhaps, and certainly by Lemaitre; as for the rest, I don’t think so.”

However, Einstein also had a fundamental disagreement with Father Lemaitre, though one — to the consternation of many in science — that was short-lived. Lemaitre used mathematics to present a model of the Universe based on Einstein’s own Theory of General Relativity which proposed that mass and energy create curvature of space-time causing particles of matter to follow a curved trajectory. Gravity, therefore, would bend not only matter, but light and even space itself. This had profound implications for science and was radically different from the reigning Newtonian physics which held that space is absolute and linear.

Even while demonstrating relativity, Einstein held to a “Steady State” theory of the Universe as being eternal, without beginning or end, and static. Using Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, Father Lemaitre created a mathematical model for the origin of the Universe concluding in 1927 that the Universe — including space and time — came into existence suddenly, some 13.7 billion years ago, from an explosive expansion of a tiny singularity that he called the “Primeval Atom.” The Universe, and time, were born on a day without yesterday. Suddenly, a created Universe was back on the scientific table and is now the scientifically accepted truth.

Father Lemaitre conceived of nothing in existence but the relatively tiny speck into which was contained all matter and energy that we now know as the Universe. In an infinitesimal fraction of a second, the Universe came into being in a moment of immeasurable heat and light. The resistance to this view within the scientific community was enormous. As Father Andrew Pinsent himself once wrote to me:

“As late as 1948 astronomers in the Soviet Union were urged to oppose the Big Bang theory because they were told it was ‘encouraging clericalism.’ People tend to forget that the world’s first atheist state in effect banned the Big Bang and genetics, both invented by priests, for more than thirty years.”

Einstein studied Lemaitre’s 1927 paper intensely, but could find no fault in the mathematics behind his proposal. Einstein would not be a slave to mathematics, however, and simply could not conceive of his instinct about the mechanics of the Universe being wrong. “Your mathematics is perfect,” he told the priest, “but your physics is abominable.” Einstein would one day take back those words.

Two years later, in 1929, the astronomer Edwin Hubble — in whose honor is named the Hubble Space Telescope — demonstrated that the Universe was in fact not only not static, as Einstein insisted, but expanding. This lent scientific weight to Father Lemaitre’s Primeval Atom because if the Universe is expanding, then logic held that in the far distant past it must have been much, much smaller while containing the same matter, mass, and energy. In fact, Physicist Stephen Hawking would decades later calculate the density of the Primeval Atom in tons per square inch to be one followed by seventy-two zeros.

Lemaitre’s model traced the origin of the Universe back 13.7 billion years to a point of immeasurable mass and density that suddenly expanded giving birth not only to matter, but to the space-time continuum itself. Appearing at a symposium with Father Lemaitre in 1933, Einstein stood and applauded the priest declaring that his view — which is today called the Standard Model of Cosmology — “Is the most beautiful explanation of creation I have ever heard.”

Cosmic Ripples

“Let there be light!” was back in the parlance of scientific truth. Though not many cosmologists were ready to embrace the Biblical account of Creation as being the sudden appearance of immense light upon the command of God, the science suddenly supported a belief in a Universe with a genesis “created from nothing.” In 1965, Bell Laboratory technicians Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson detected the background radiation from the Big Bang. They were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery of the background signature of Father Lemaitre’s expansion of the Universe on a day without yesterday.

Early in 2014, astronomers announced the discovery of Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation permeating the Universe caused from the ripples left over from the moment of the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago. Even for the rigors of science and what constitutes proof, there is no longer reasonable doubt within reputable science that Father Georges Lemaitre was right.

But if you are having trouble bending your mind around all this, please don’t ask what God did before the Big Bang. On that day, time itself was created so there was no “before.” That’s a mind-boggling post for another day. And as for those theories about multiple worlds and parallel universes that Mary Anne O’Hare wanted my opinion on, the idea is theoretical, entirely without evidence, and not technically, at this juncture, in the realm of science. In a terrific book, Why Science Does Not Disprove God (William Morrow 2014) mathematician-author Amir D. Aczel described multiverse theory as a sort of “atheism of the gaps,” an attempt to plug theoretical scientific holes with anything BUT religious ideas. As G.K. Chesterton once said:

“People who do not believe in God do not believe in nothing. They believe in anything!”

The great contemporary priest-scientist, Father Robert Spitzer, SJ, wrote a wonderful book about God’s intervention in our science, Christ, Science, and Reason. Father Spitzer referred to Father Georges Lemaitre as “the founder of modern cosmology.” He quoted Albert Einstein as stating that Father Lemaitre’s discovery “is the finest description of Creation that I have ever heard.” We should find great hope in the fact that the Catechism of the Catholic Church and the findings of modern cosmology are now on the same page about the origin of the Universe as coming into existence “out of nothing.” We should have no fear after that. Surely, the God Who could do this would have no problem arranging eternal life for us who believe.

Another friend just came by to ask me what I am writing about. Finally, my moment had arrived! “What do you know about the Big Bang Theory?” I asked. The young man pondered the question for a moment then said, “I like Sheldon the best.” I can’t win!

+ + +

Important Message to Readers of Beyond These Stone Walls:

In 2020, 11 years after this blog began, we were forced to shut it down and start over. I described the circumstances for this in a 2020 post, “Life Goes On Behind and Beyond These Stone Walls.”

However, this transition left over 500 posts behind in the older version of this blog, but still discoverable in search engines, but without proper formatting.

Restoring and updating 500+ posts is a daunting task. So I choose posts to update based on how often they show up in reader searches. It amazes me that hundreds of our older posts are still being routinely read.

This week’s post was first published in 2014, but it shows up repeatedly in new searches. So we have restored and substantially updated it with new information for posting anew.

You may also like these related posts which have also been restored:

Life Goes On Behind and Beyond These Stone Walls

Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang

“A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and The Big Bang

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Saints Alive! When Padre Pio and the Stigmata Were on Trial

Padre Pio was proclaimed a living saint for the wounds he bore for Christ, but his reputation for sanctity became another wound, this one inflicted from the Church.

Padre Pio was proclaimed a living saint for the wounds he bore for Christ, but his reputation for sanctity became another wound, this one inflicted from the Church.

September 20, 2023 by Fr Gordon MacRae

“Six Degrees of Separation,” a famous play by John Guare, became a 1993 film starring Will Smith, Donald Sutherland, and Stockard Channing. The plot revolved around a theory proposed in 1967 by sociologists Stanley Milgram and Frigyes Karinthy. Wikipedia describes “Six Degrees of Separation” as:

“The idea that everyone is at most six steps away from any other person on Earth, so that a chain of ‘a friend of a friend’ statements can be made to connect any two people in six steps or fewer.”

It’s an intriguing idea, and sometimes the connections are eerie. In “A Day Without Yesterday” I wrote about my long-time hero, Fr. Georges Lemaitre, the priest-physicist who changed the mind of Albert Einstein on the creation of the Universe. A few weeks after my post, a letter arrived from my good friend, Pierre Matthews in Belgium. Pierre sent me a photo of himself as a young man posing with his family and a family friend, the famous Father Lemaitre, in Switzerland in 1956. In a second photo, Pierre had just served Mass with the famous priest who later autographed the photo.

When I wrote of Father Lemaitre, I had no idea there are but two degrees of separation between me and this famous priest-scientist I’ve so long admired. The common connection we share with Pierre Matthews — not to mention the autographed photo — left me awestruck. The mathematical odds against such a connection are staggering. Something very similar happened later and also involving Pierre Matthews. It still jolts my senses when I think of it. The common bond this time was with Saint Padre Pio.

When Pierre visited me in prison in 2010, I told him about this blog which had been launched months earlier. When I told Pierre that I chose Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio as the patrons of Beyond These Stone Walls, Pierre quietly and modestly said, “I’ve met Padre Pio.”

Pierre’s casual remark dropped like a bomb on our conversation. What were the odds that I would be sitting at a table in the prison visiting room with a man who traveled from Europe to tell me of how he met Padre Pio. The saint imposed his wounded and bandaged hands in blessing upon Pierre’s head over a half century earlier.

The labyrinthine ways of grace are far beyond my understanding. Pierre told me that as a youth growing up in Europe, his father enrolled him in a boarding school. When he wrote to his father about a planned visit to central Italy, his father instructed him to visit San Giovanni Rotondo and ask for Padre Pio’s blessing. Pierre, a 16-year-old at the time, had zero interest in visiting Padre Pio. But he obediently took a train to San Giovanni Rotondo. He waited there for hours. Padre Pio was nowhere to be seen.

Pierre then approached a friar and asked if he could see Padre Pio. ‘Impossible!’ he was told. Just then, he looked up and saw the famous Stigmatic walking down the stairs toward him. Padre Pio’s hands were bandaged and he wore gloves. The friar, following the young man’s gaze, whispered in Italian, ‘Do not touch his hands.’ Pierre trembled as Padre Pio approached him. He placed his bandaged hands upon Pierre’s head and whispered his blessing.

Fifty-five years later, in the visiting room of the New Hampshire State Prison, Pierre bowed his head and asked for my blessing. It was one of the most humbling experiences of my life. I placed my hand upon Pierre knowing that the spiritual imprint of Padre Pio’s blessing was still in and upon this man, and I was overwhelmed to share in it.

This wasn’t the first time I shared space with Padre Pio. Several years ago, in November 2005, we shared the cover of Catalyst, the Journal of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. I also share a painful date with Padre Pio. September 23 was the date he died in 1968. On September 23, 1994 I was put into chains and taken to prison to begin a life sentence for crimes that never took place.

That’s why we shared that cover of Catalyst. Catholic League President Bill Donohue wrote of his appearance on NBC’s “Today” show on October 13, 2005 during which he spoke of my trial and imprisonment declaring, “There is no segment of the American population with less civil liberties protection than the average American Catholic priest.” That issue of Catalyst also contained my first major article for The Catholic League, “Sex Abuse and Signs of Fraud” written from prison in 2005.

The Indictment of Heroic Virtue

Padre Pio was on that Catalyst cover because three years after he was canonized in 2002 by Pope John Paul II, Atlantic Monthly magazine carried a brief article by Tyler Cabot entitled “The Rocky Road to Sainthood” (November 2005). Of one of the most revered priests in Church history, Cabot wrote:

“Despite questions raised by two papal emissaries – and despite reported evidence that he raised money for right-wing religious groups and had sex with penitents – [Padre] Pio was canonized in 2002.”

I’m not sure whether the bigger scandal for Tyler Cabot and Atlantic Monthly was the sexual accusation or “raising money for right-wing religious groups.” Bill Donohue expressed surprise that such a “highly regarded magazine would publish such trash.” I was more dismayed than surprised by the irresponsibility. Yes, it’s irresponsible to tell half the story and present it as the truth.

It wasn’t the first time such attacks were launched against Padre Pio. Four years before his canonization, and thirty years after his death, The New York Times (September 24, 1998) carried an article charging that Padre Pio was the subject of no less than twelve Vatican investigations in his lifetime, and one of the investigations alleged that “Padre Pio had sex with female penitents twice a week.” It’s true that this was alleged, but it’s not the whole truth. The New York Times and Atlantic Monthly were simply following an agenda that should come as no surprise to anyone. I’ll describe below why these wild claims fell apart under scrutiny.

But first, I must write the sordid story of why Padre Pio was so accused. That’s the real scandal. It’s the story of how Padre Pio responded with heroic virtue to the experience of being falsely accused repeatedly from within the Church. His heroic virtue in the face of false witness is a trait we simply do not share. It far exceeds any grace ever given to me.

Twice Stigmatized

Early in the morning of September 20, 1918, at the age of 31, Francesco Forgione, known to the world as Padre Pio, received the Stigmata of Christ. He was horrified, and he begged the Lord to reconsider. Each morning in the month to follow, Padre Pio awoke with the hope that the wounds would be gone. He was terrified. After a month with the wounds, Padre Pio wrote a note to Padre Benedetto, his spiritual advisor, describing in simple, matter-of-fact terms what happened to him on that September 20 morning:

“On the morning of the 20th of last month, in the choir, after I had celebrated Mass . . . I saw before me a mysterious person similar to the one I had seen on the evening of 5 August. The only difference was that his hands and feet and side were dripping blood. The sight terrified me and what I felt at that moment is indescribable. I thought I should die and really should have died if the Lord had not intervened and strengthened my heart which was about to burst out of my chest.

“The vision disappeared and I became aware that my hands and feet and side were dripping blood. Imagine the agony I experienced and continue to experience almost every day. The heart wound bleeds continually, especially from Thursday evening until Saturday.

“Dear Father, I am dying of pain because of the wounds and the resulting embarrassment I feel in my soul. I am afraid I shall bleed to death if the Lord does not hear my heartfelt supplication to relieve me of this condition.

“Will Jesus, who is so good, grant me this grace? Will he at least free me from the embarrassment caused by these outward signs? I will raise my voice and will not stop imploring him until in his mercy he takes away . . . these outward signs which cause me such embarrassment and unbearable humiliation.”

— Letters 1, No. 511

And so it began. What Padre Pio faced that September morning set in motion five decades of suspicion, accusation, and denunciation not from the secular world, but from the Catholic one. From within his own Church, Padre Pio’s visible wounds brought about exactly what he feared in his pleading letter to his spiritual director. The wounds signified in Padre Pio exactly what they first signified for the Roman Empire and the Jewish chief priests at the time Christ was crucified. They were the wounds of utter humiliation.

Within a year, as news of the Stigmata spread throughout the region, the people began to protest a rumor that Padre Pio might be moved from San Giovanni Rotondo. This brought increased scrutiny within the Church as the stories of Padre Pio’s special graces spread throughout Europe like a wildfire.

By June of 1922, just four years after the Stigmata, the Vatican’s Holy Office (now the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith) began to restrict the public’s access to Padre Pio who was accused of self-inflicting his own wounds and sexually abusing penitents. He was even accused of being a political agitator for a fascist group, and helping to incite a riot. His accusers included fellow friars, and neighboring priests, bishops, and archbishops increasingly threatened by Padre Pio’s growing fame and influence. A physician and founder of Rome’s Catholic university hospital labeled Padre Pio, sight unseen, “an ignorant and self-mutilating psychopath who exploited peoples’ credulity.”

Padre Pio and I have this one thing in common. You would not believe some of the things I’ve been called, sight unseen, by people presenting themselves as the voice of the faithful.

From 1924 to 1931, accusation after accusation was investigated by the Holy See which issued a series of official statements denying the supernatural origin of Pio’s wounds and the legitimacy of his gifts. At one point, the charge that his wounds were self-inflicted was withdrawn. Several legitimate examinations found no evidence for this. It was then charged that Padre Pio’s wounds were psychologically self-induced because of his “persistent concentration on the passion of Christ.”

Finally, in the one instance in which I can personally relate to Padre Pio, he responded with sheer exasperation at his accusers: “Go out to the fields,” he wrote, “and look very closely at a bull. Concentrate on him with all your might. Do this and see if horns grow on your head!”

By June of 1931, Padre Pio was receiving hundreds of letters daily from the faithful asking for prayers. Meanwhile, the Holy See ordered him to desist from public ministry. He was barred from offering Mass in public, barred from hearing confessions, and barred from any public appearance as sexual abuse charges against him were formally investigated — again. Padre Pio was a “cancelled priest” long before it became “a thing” in the Church.

Finally, in 1933, Pope Pius XI ordered the Holy Office to reverse its ban on Padre Pio’s public celebration of Mass. The Holy Father wrote, closing the investigation: “I have not been badly disposed toward Padre Pio, but I have been badly informed.” Over the succeeding year his faculties to function as a priest were progressively restored. He was permitted to hear men’s confessions in March of 1934 and the confessions of women two months later.

Potholes on the Road to Sainthood

The accusations of sexual abuse, insanity, and fraud did not end there. They followed Padre Pio relentlessly for years. In 1960, Rome once again restricted his public ministry citing concerns that his popularity had grown out of control.

An area priest, Father Carlo Maccari, added to the furor by once again accusing the now 73-year-old Padre Pio of engaging in sex with female penitents “twice a week.” Father Maccari went on to become an archbishop, then admitted to his lie and asked for forgiveness in a public recantation on his deathbed.

When Padre Pio’s ministry was again restored, the daily lines at his confessional grew longer, and the clamoring of all of Europe seeking his blessing and his prayers grew louder. It was at this time that my friend, Pierre Matthews encountered the beleaguered and wounded saint on the stairs at San Giovanni.

The immense volume of daily letters from the faithful also continued. In 1962, Padre Pio received a pleading letter from Archbishop Karol Wotyla of Krakow in Poland. The Archbishop’s good friend, psychiatrist Wanda Poltawska, was stricken with terminal cancer and the future pope took a leap of faith to ask for Padre Pio’s prayers. When Dr. Poltawska appeared for surgery weeks later, the mass of cancer had disappeared. News of the miraculous healing reached Archbishop Wotyla on the eve of his leaving for Rome on October 5, 1962 for the convening of the Second Vatican Council.

Former Newsweek Religion Editor Kenneth Woodward wrote a riveting book entitled Making Saints (Simon & Shuster, 1990). In a masterfully written segment on Padre Pio twelve years before his canonization, Kenneth Woodward interviewed Father Paolo Rossi, the Postulator General of the Capuchin Order and the man charged with investigating Padre Pio’s cause for sainthood. Fr. Rossi was asked how he expects to demonstrate Padre Pio’s heroic virtue. The priest responded:

“People would better understand the virtue of the man if they knew the degree of hostility he experienced from the Church . . . The Order itself was told to act in a certain way toward Padre Pio. The hostility went all the way up to the Holy Office, and the Vatican Secretariat of State. Faulty information was given to the Church authorities and they acted on that information.”

— Making Saints, p.188

It is one of the Church’s great ironies that Saint Padre Pio was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 2002 just as the U.S. bishops were implementing a response to the newest media furor about accused U.S. priests. I am one of those priests. The irony is that if the charter the bishops adopted was imposed in Italy forty years earlier, Padre Pio may have been denied any legitimate chance of ever clearing his name. The investigations that eventually exposed those lies simply do not take place in the current milieu.

I’ll live with that irony, and I’m glad Padre Pio didn’t have to. Everything else he wrote to his spiritual director on that fateful morning of September 20, 1918 came to pass. He suffered more than the wounds of Christ. He suffered the betrayal of Christ by Judas, and the humiliation of Christ, and the scourging of Christ, and he suffered them relentlessly for fifty years. As Father Richard John Neuhaus wrote of him in First Things (June/July 2008):

“With Padre Pio, the anguish is not the absence of God, but the unsupportable weight of His presence.”

Fifty years after receiving the Stigmata, Padre Pio’s wounds disappeared. They left no scar — no trace that he ever even had them. Three days later, on September 23, 1968, Padre Pio died. I was fifteen years old — the age at which he began religious life.

In April, 2010, the body of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina was moved from its shrine at San Giovanni Rotondo to a new church dedicated in his honor in 2009 by Pope Benedict XVI. Padre Pio’s tomb is the third most visited Catholic shrine in the world after the Vatican itself and the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City.

The New York Times might still spread another story, but the people of God have spoken. Padre Pio was canonized by the sensus fidelium — by the near universal acclaim of believers long before the Church ratified their belief. Padre Pio is a saint of the people.

Some years ago, a priest in Dallas — who read of Padre Pio’s “Patron Saint” status on our About Page sent me a relic of Saint Pio encased in plastic. He later wrote that he doesn’t know why he sent it, and realized too late that it might not make it passed the prison censors. Indeed, the relic was refused by prison staff because they couldn’t figure out what it was. Instead of being returned to sender as it should have been, it made its way somehow to the prison chaplain who gave it to me.

The relic of Saint Pio is affixed on my typewriter, just inches from my fingers at this moment. It’s a reminder, when I’m writing, of his presence at Beyond These Stone Walls, the ones that imprison me and the one I write for. The relic’s card bears a few lines in Italian by Padre Pio:

“Due cose al mondo non ti abbandonano mai, l’occhio di Dio che sempre ti vede e il cuore della mamma che sempre ti segue.”

“There are two things in the world that will never forsake you: the eye of God that always sees you, and the heart of His Mother that always follows you.”

— Padre Pio

Saints alive! May I never forget it!

+ + +

EPILOGUE

In 2017, Pierre Matthews, my friend and Pornchai Moontri’s Godfather, passed from this life. After his death someone in his family sent me a photograph of him kneeling at the Shrine of Saint Padre Pio where he offered prayers for me and for Pornchai.

+ + +

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

For Those Who Look at the Stars and See Only Stars

An MIT astrophysicist trying to reconcile science with a quest for spiritual truth wrote upon the death of his parents, “I wish I believed.” I believe he just might.

First deep field image from the James Webb Space Telescope. Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA and STScl

An MIT astrophysicist trying to reconcile science with a quest for spiritual truth wrote upon the death of his parents, “I wish I believed.” I believe he just might.

July 5, 2023 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: The image atop this post is the first of many images transmitted by the James Webb Space Telescope parked one million miles from Earth in 2022 to survey the Cosmos. I first wrote this post in 2018 for an older version of this blog. It needed to be restored for our readers, but I ended up completely rewriting it. My goal was to highlight a bridge between science and faith, but some say it also highlights a bridge between life and death.

+ + +

When Beyond These Stone Walls was just a few months old back in 2009, I wrote a post about the death of my mother. It told a story about an event that occurred on her birthday a year after she died. At first glance it seemed an ordinary event, the sort of thing usually chalked up to coincidence. But its meaning and timing and how it unfolded made it an extraordinary grace beyond comprehension. It required that I set aside the mathematical odds against such a thing and see it foremost in the light of faith.

It remains to this day a pivotal moment, a wondrous event that shook my faith out of the closet of doubt where I tend to store it when times get rough — which is often. The story told in that post may shake you, too, if it hasn’t already. By that, I do not mean that it will challenge your faith. It’s just the opposite. My story lifted for me a corner of the veil between doubt and belief. So the title I gave it was “A Corner of the Veil.”

My friend, Pornchai Moontri was with me that night when the event occurred while I offered Mass in our prison cell. I asked Pornchai if he remembers it. “How could I forget it?” he said. He described it as an “ordinary miracle,” the kind he says he has seen a lot of since his eyes were opened.

I could repeat the whole story here, but it will take too long and I have written it once already. It is but a mere click away. I will link to it again after this post. You can decide for yourself whether the story it tells is mere coincidence or something more. My analytic brain tends toward coincidence, but sometimes that just doesn’t add up. This was one of those times.

I then came upon a strange little book of fiction by Laurence Cossé first published in French as Le Coin du Voile, and in English, A Corner of the Veil (Scribner 1999). It strangely fell at my feet from a library shelf after my post with the same title.

Laurence Cossé was a journalist for Radio France when she wrote this book described by Notre Dame theologian Ralph McInerney as “a theological thriller that makes a mystery out of the absence of mystery.” It is a spellbinding account of what happens to the people and institutions of Church and State when a manuscript surfaces that irrefutably proves the existence of God.

Science, religion, and politics all transform as their experts ponder its meaning and their own continued relevancy. The reader is left to wonder whether the discovery will spark a new era of harmony or launch the final battle of the apocalypse.

“Six pages further, Father Bertrand was trembling. The proof was neither arithmetical nor physical nor esthetical nor astronomical, it was irrefutable. Proof of God’s existence had been achieved. Bertrand was tempted, for a second, to toss the bundle into the wastebasket.” (p 15)

As it does for people who awaken to faith on a personal level, the discovery immediately altered the way its readers face both life and death. The transformation was astonishing. Death came to be seen, not as an entity unto itself, but as it really is a chapter in the continuity of life, of me, of the person I call "myself," integrated into the Great Tapestry of God.

I happen to know a lot of people whose experience of living is suddenly overshadowed by the prospect of dying. They have come to know that death is drawing nearer day by day. Some of them struggle. What does death mean, and why do we wage such war against it? The age of individualism and relativism distorts death into a fearsome enemy. As Dylan Thomas wrote,

“Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, Rage against the dying of the light.”

Carina Nebula image from the James Webb Space Telescope. Credits: NASA, ESA, CSA and STScl

If That’s All There Is, Then Let’s Keep Dancing!

While writing this post, I received a letter from a reader in Ohio who asked me to write a note of encouragement to a friend whose death is drawing near. After a lifetime of faith, he wrote, the friend is having grave doubts and fears about the end of life and the finality of death. He is asking the age-old question put to song: “Is that all there is?”

But that is our problem. We speak in terms of “finality” as though when faced with death, all that we once believed with hope takes on the trappings of a mere children’s fantasy. I know too many people who are dying, and many of us treat it as the silent elephant in the room because we know that sooner or later we will join them just as our parents did before us. It is part of the flow of life, but we ward it off as a terror in the night. In the face of death, science alone comes up empty.

When you think of it, death is best seen as an act of love. Imagine the inherent selfishness of a humanity without death. Those we love the most in this world — those who fulfill our very purpose for being in this world — would be left out of existence if this life were ours alone to keep. But facing death with no life of faith casts both life and death into a formless, meaningless void.

I recently came across a review of a book by noted MIT physicist and astronomer Alan Lightman entitled Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine (Pantheon 2018). It was reviewed by UMass physics professor Alan Hirshfeld in “A Longing for Truth and Meaning” in The Wall Street Journal April 7-8, 2018).

In some previous science posts here at Beyond These Stone Walls, I have cited both writers for other books and articles they have written. Mr. Lightman’s book, and Mr. Hirshfeld’s review of it, both raise provocative questions about “the core mysteries of human life” and the way science explores the Universe:

“Why are we here? What, if anything, is the meaning of existence? Is there a God? Is there life after death? Whence consciousness?”

I am very happy to see science ponder these questions, but they can never be answered by science alone. It comes up short when the task moves beyond the mere physics and chemistry of life to its meaning and purpose. Consider this explanation of the self, of who and what you are as a conscious being, offered by Mr. Lightman:

“Self is the name we give to the mental sensation of certain electrical and chemical flows in our neurons.”

It is too tempting for science to reduce us to fundamental biology and chemistry, but the mere mechanics of what I am do not at all define who I am. If science is the only contribution to the meaning of life and death, then it becomes obvious why so many spend significant time in denial or in dread of death.

In his new book reflecting on the Cosmos, MIT astrophysicist Alan Lightman takes up these questions and more. Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine is a view of the world through a scientist’s lens which requires the scientist to see in it, as Alan Hirshfeld describes,

“Tangible bits of matter and energy, all governed by a set of fundamental physical laws … In keeping with his ‘Central Doctrine of Science,’ he eschews unprovable hypotheses, most significantly the existence of God and the afterlife.”

But these hypotheses are only unprovable from the point of view of science which concerns itself, as it concerns astrophysicist Alan Lightman, with matter and energy and fundamental laws. But Professor Lightman has acquired the wisdom not to stop there. His reflection on the death of his parents brings him to the “impossible truth” that they no longer exist, and he will one day follow them into this nonexistence.

Is that all there is? “I wish I believed,” he wrote. But “a precipice looms for each of us, an eventual plunge into nonexistence.” As Alan Hirshfeld described it:

“A depressing prospect, for sure, yet the inevitable judgment of those for whom religious or spiritual alternatives carry no resonance.”

Pictured: Fr. Georges Lemaître, Albert Einstein and Fr. Andrew Pinsent

Threads of the Tapestry of God

I have written numerous articles about the sciences of astronomy and cosmology, the origins and mechanics of the Universe. But these are not the only tools with which to explore the universe and measure life and death. The conclusions of science and faith are not as inseparable as science might have you believe.

I have raised this analogy before, but consider these two passages from two sources that have become meaningful to me. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC 296) expresses a fundamental truth of faith God created the Universe and life “out of nothing.”

Among the many contributions of science that I hold in high regard, this is one by the mathematician Robyn Arianrhod whose book, Einstein’s Heroes: Imagining the World Through the Language of Mathematics (Oxford University 2005) draws the same conclusion. Don’t let the scientific language dissuade you from understanding this phenomenal bridge between science and faith:

“The Belgian priest and astrophysicist, Georges Lemaitre began to develop expanding cosmological models out of Einstein’s equations … In 1931, Lemaitre formally sowed the seeds of the Big Bang theory [which] showed that Einstein’s equations predicted the universe had expanded not from a tiny piece of matter located in an otherwise empty cosmos, but from a single point in four-dimensional spacetime … Before this point, about 13 billion years ago, there was no time and no space. No geometry, no matter. Nothing. The universe simply appeared out of nowhere. Out of nothing.”

— Arianrhod, pp 185-187