“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Of Saints and Souls and Earthly Woes

For Catholics, the month of November honors our beloved dead, and is a time to reenforce our civil liberties especially the one most endangered: Religious Freedom.

For Catholics, the month of November honors our beloved dead, and is a time to reinforce our civil liberties especially the one most endangered: Religious Freedom.

The Commemoration of All Saints and All Souls by Fr. Gordon MacRae

A lot of attention has been paid to a recent post by Pornchai Moontri. Writing in my stead from Thailand, his post was “Elephants and Men and Tragedy in Thailand.” Many readers were able to put a terrible tragedy into spiritual perspective. Writer Dorothy R. Stein commented on it: “The Kingdom of Thailand weeps for its children. Only a wounded healer like Mr. Pornchai Moontri could tell such a devastating story and yet leave readers feeling inspired and hopeful. This is indeed a gift. I have read many accounts of this tragedy, but none told with such elegant grace.”

A few years ago I wrote of the sting of death, and the story of how one particular friend’s tragic death stung very deeply. But there is far more to the death of loved ones than its sting. A decade ago at this time I wrote a post that helped some readers explore a dimension of death they had not considered. It focused not only on the sense of loss that accompanies the deaths of those we love, but also on the link we still share with them. It gave meaning to that “Holy Longing” that extends beyond death — for them and for us — and suggested a way to live in a continuity of relationship with those who have died. The All Souls Day Commemoration in the Roman Missal also describes this relationship:

“The Church, after celebrating the Feast of All Saints, prays for all who in the purifying suffering of purgatory await the day when they will join in their company. The celebration of the Mass, which re-enacts the sacrifice of Calvary, has always been the principal means by which the Church fulfills the great commandment of charity toward the dead. Even after death, our relationship with our beloved dead is not broken.”

That waiting, and our sometimes excruciatingly painful experience of loss, is “The Holy Longing.” The people we have loved and lost are not really lost. They are still our family, our friends, and our fellow travelers, and we shouldn’t travel with them in silence. The month of November is a time to restore our spiritual connection with departed loved ones. If you know others who have suffered the deaths of family and friends, please share with them a link to “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.”

The Communion of Saints

I have written many times about the saints who inspire us on this arduous path. The posts that come most immediately to mind are “A Tale of Two Priests: Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul II,” and more recently, “With Padre Pio When the Worst that Could Happen Happens.” Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Saint Padre Pio inspire me not because I have so much in common with them, but because I have so little. I am not at all like them, but I came to know them because I was drawn to the ways they faced and coped with adversity in their lives on Earth.

Patron saints really are advocates in Heaven, but the story is bigger than that. To have patron saints means something deeper than just hoping to share in the graces for which they suffered. It means to be in a relationship with them as role models for our inevitable encounter with human trials and suffering. They can advocate not only for us, but for the souls of those we entrust to their intercession. In the Presence of God, they are more like a lens for us, and not dispensers of grace in their own right. The Protestant critique that Catholics “pray to saints” has it all wrong.

To be in a relationship with patron saints means much more than just waiting for their help in times of need. I have learned a few humbling things this year about the dynamics of a relationship with Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio. I have tried to consciously cope with painful things the way they did, and over time they opened my eyes about what it means to have their advocacy. It is an advocacy I would not need if I were even remotely like them. It is an advocacy I need very much, and can no longer live without.

I don’t think we choose the saints who will be our patrons and advocates in Heaven. I think they choose us. In ways both subtle and profound, they interject their presence in our lives. I came into my unjust imprisonment decades ago knowing little to nothing of Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio. But in multiple posts at Beyond These Stone Walls I have written of how they made their presence here known. And in that process, I have learned a lot about why they’re now in my life. It is not because they look upon me and see their own paths. It is because they look upon me and see how much and how easily I stray from their paths.

I recently discovered something about the intervention of these saints that is at the same time humbling and deeply consoling. It is consoling because it affirms for me that these modern saints have made themselves a part of what I must bear each day. It is humbling because that fact requires shedding all my notions that their intercession means a rescue from the crosses I would just as soon not carry.

Over the last few years, I have had to live with something that is very painful — physically very painful — and sometimes so intensely so that I could focus on little else. In prison, there are not many ways to escape from pain. I can purchase some over-the-counter ibuprophen in the prison commissary, but that’ is sort of like fighting a raging forest fire with bottled water. It is not very effective. At times, the relentless pain flared up and got the better of me, and I became depressed. There are not many ways to escape depression in prison either. The combination of nagging pain and depression began to interfere with everything I was doing, and others started to notice. The daily barrage of foul language and constantly loud prison noise that I have heard non-stop for decades suddenly had the effect of a rough rasp being dragged across the surface of my brain. Many of you know exactly what I mean.

So one night, I asked Saint Padre Pio to intercede that I might be delivered from this awful nagging pain. I fell off to sleep actually feeling a little hopeful, but it was not to be. The next morning I awoke to discover my cross of pain even heavier than the night before. Then suddenly I became aware that I had just asked Padre Pio — a soul who in life bore the penetrating pain of the wounds of Christ without relief for fifty years — to nudge the Lord to free me from my pain. What was I thinking?! That awareness was a spiritually more humbling moment than any physical pain I have ever had to bear.

So for now, at least, I will live with this pain, and even embrace it, but I am no longer depressed about it. Situational depression, I have learned, comes when you expect an outcome other than the one you have. I no longer expect Padre Pio to rescue me from my pain, so I am no longer depressed. I now see that my relationship with him is not going to be based upon being pain-free. It is going to be what it was initially, and what I had allowed to lapse. It is the example of how he coped with suffering by turning himself over to grace, and by making an offering of what he suffered.

A rescue would sure be nice, but his example is, in the long run, a lot more effective. I know myself. If I awake tomorrow and this pain is gone forever, I will thank Saint Padre Pio. Then just as soon as my next cross comes my way — as I once described in “A Shower of Roses” — I will begin to doubt that the saint had anything to do with my release.

His example, on the other hand, is something I can learn from, and emulate. The truth is that few, if any, of the saints we revere were themselves rescued from what they suffered and endured in this life. We do not seek their intercession because they were rescued. We seek their intercession because they bore all for Christ. They bore their own suffering as though it were a shield of honor and they are going to show us how we can bear our own.

For Greater Glory

Back in 2010 when my friend Pornchai Moontri was preparing to be received into the Church, he asked one of his “upside down” questions. I called them “upside down” questions because as I lay in the bunk in our prison cell reading late at night, his head would pop down from the upper bunk so he appeared upside down to me as he asked a question. “When people pray to saints do they really expect a miracle?” I asked for an example, and he said, “Should you or I ask Saint Maximilian Kolbe for a happy ending when he didn’t have one himself?”

I wonder if Pornchai knew how incredibly irritating it was when he stumbled spontaneously upon a spiritual truth that I had spent months working out in my own soul. Pornchai’s insight was true, but an inconvenient truth — inconvenient by Earthly hopes, anyway. The truth about Auschwitz, and even a very long prison sentence, was that all hope for rescue was the first hope to die among any of its occupants. As Maximilian Kolbe lay in that Auschwitz bunker chained to, but outliving, his fellow prisoners being slowly starved to death, did he expect to be rescued?

All available evidence says otherwise. Father Maximilian Kolbe led his fellow sufferers into and through a death that robbed their Nazi persecutors of the power and meaning they intended for that obscene gesture. How ironic would it be for me to now place my hope for rescue from an unjust and uncomfortable imprisonment at the feet of Saint Maximilian Kolbe? Just having such an expectation is more humiliating than prison itself. Devotion to Saint Maximilian Kolbe helped us face prison bravely. It does not deliver us from prison walls, but rather from their power to stifle our souls.

I know exactly what brought about Pornchai’s question. Each weekend when there were no programs and few activities in prison, DVD films were broadcast on a closed circuit in-house television channel. Thanks to a reader, a DVD of the soul-stirring film, “For Greater Glory” was donated to the prison. That evening we were able to watch the great film. It was an hour or two after viewing this film that Pornchai asked his “upside-down” question.

“For Greater Glory” is one of the most stunning and compelling films of recent decades. You must not miss it. It is the historically accurate story of the Cristero War in Mexico in 1926. Academy Award nominee Andy Garcia portrays General Enrique Gorostieta Delarde in a riveting performance as the leader of Mexico’s citizen rebellion against the efforts of a socialist regime to diminish and then eradicate religious liberty and public expressions of Christianity, especially Catholic faith.

If you have not seen “For Greater Glory,” I urge you to do so. Its message is especially important before drawing any conclusions about the importance of the issue of religious liberty now facing Americans and all of Western Culture. As readers in the United States know well, in 2026 we face a most important election for the future direction of Congress and the Senate.

“For Greater Glory” is an entirely true account, and portrays well the slippery slope from a government that tramples upon religious freedom to the actual persecution, suppression and cancelation of priests and expressions of Catholic faith and witness. If you think it could not happen here, think again. It could not happen in Mexico either, but it did. We may not see our priests publicly executed, but we are already seeing them in prison without due process, and even silenced by their own bishops, sometimes just for boldly speaking the truth of the Gospel. You have seen the practice of your faith diminished as “non-essential” by government dictate during a pandemic.

The real star of this film — and I warn you, it will break your heart — is the heroic soul of young José Luis Sánchez del Río, a teen whose commitment to Christ and his faith resulted in horrible torment and torture. If this film were solely the creation of Hollywood, there would have been a happy ending. José would have been rescued to live happily ever after. It is not Hollywood, however; it is real. José’s final tortured scream of “Viva Cristo Rey!” is something I will remember forever.

I cried, finally, at the end as I read in the film’s postscript that José Luis Sánchez del Río was beatified as a martyr by Pope Benedict XVI after his elevation to the papacy in 2005. Saint José was canonized October 16, 2016 by Pope Francis, a new Patron Saint of Religious Liberty. His Feast Day is February 10. José’s final “Viva Cristo Rey!” echoes across the century, across all of North America, across the globe, to empower a quest for freedom that can be found only where young José found it.

“Viva Cristo Rey!”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Our Faith is a matter of life and death, and it diminishes to our spiritual peril. Please share this post. You may also like these related posts to honor our beloved dead in the month of November.

Elephants and Men and Tragedy in Thailand

The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts

The God of the Living and the Life of the Dead

The commemoration of our beloved dead on All Souls Day has roots in ancient Christian tradition, Faith in the God of Life in the land of the living survives death.

The commemoration of our beloved dead on All Souls Day has roots in ancient Christian tradition, Faith in the God of Life in the land of the living survives death.

Introduction from Fr. Gordon MacRae: In the last days of October 2020, I wrote a special post to commemorate All Souls Day and to honor our beloved dead. One reviewer called it “A tour de force of Sacred Scripture on the most crucial question of all time: the meaning of life and death.” I’m not sure it actually rises to that level, but I thought it was an okay post.

It was the last one published at These Stone Walls, the older version of this blog that one week later was taken down and then reborn anew as Beyond These Stone Walls. I wrote of how and why that happened in “Life Goes On, Behind and Beyond These Stone Walls.”

It was not planned this way, but my post to mark the commemoration of All Souls was published in the midst of a global pandemic just days before the most contentious U.S. presidential election of modern time. That was also the time in which my friend, Pornchai Moontri, had been handed over to ICE for a long and grueling ordeal leading up to deportation to his native Thailand.

For many readers, my All Souls Day post was relegated to a far back burner then so I have decided to rewrite it and post it anew. It is, after all, a matter of life and death. Please ponder it and share it with others.

Like all of you reading this, I, too, have been touched by death in ways that have changed my life. I once wrote of how death left me not only grieving, but entirely alone and stranded. It was a post about the essence of Purgatory and why it should not be feared. That post — which I highly recommend if you have ever been touched by death, is “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.”

It is one of the mysteries of Sacred Scripture that certain concepts exist there in almost equal measure with their polar opposites. I wrote during Holy Week, 2020, of the presence of both good and evil at the same table in “Satan at the Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light.” Many readers expressed amazement at my revelation that the concepts of light and darkness are represented in Scripture in almost equal measure, but with light just only slightly more prevalent.

I was surprised, for this post, to discover that the same is true in the matter of life and death. I conducted some research into the various permutations of the word, “death” in Sacred Scripture. The terms, death, dead, die, died, and killed have a combined appearance for a total of 1,620 times in our Old and New Testaments. The same research into occurrences of the word, “life” included the terms, life, alive, living, lives and lived. The combined appearances of “life” totaled 1,621. Pro-life wins!

Our Scriptures, and especially their revelations in the words of Jesus who had … well … the “inside scoop,” not only give life and death almost equal weight, but place them on a continuum. This becomes most evident in a challenge of Jesus to the Sadducees who rejected any notion of an afterlife or resurrection:

“You are wrong, because you know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God … And as for the resurrection from the dead, have you not read what was said to you by God? ‘I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.’ He is not the God of the dead, but of the living.”

Jesus was citing the Book of Exodus (3:1-6) and the story of Moses’ first encounter with God in the burning bush. By Yahweh’s self-description that he is the God of these Patriarchs who died long ago, Jesus brings his listeners to a conclusion that they must still live for God to still be their God. Their ongoing presence with God is the decisive precondition for future resurrection.

For Jesus, this ongoing presence of the soul with God is a continuation of the very life you know — but without the excess baggage. What must such a state be like? I sometimes hear from people who long to have some affirmation from their departed loved ones that they still exist. Do we really need such evidence? One of the most hopeful verses in all of Scripture comes from Saint Paul’s Letter to the Colossians, and it has an answer:

“If with Christ you died to the elemental spirits of the universe, why do you live as if you still belonged to the world?… If then you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above where Christ is seated at the right hand of God. Set your mind on things that are above, not on things that are on Earth. For you have died, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God.”

The Resurrection and the Life

There is another way to phrase what I wrote above: “For Jesus, this ongoing presence of the soul with God is a continuation of the very life you know…” It is also a continuation of the very life that knows you. It is that which is imparted in our ensoulment as being “in the image and likeness of God” (Gen. 1:26). In the Biblical account of creation, filled with rich theological meaning, “The Lord God formed man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being” (Genesis 2:7). I wrote of this once in “Inherit the Wind: Pentecost and the Breath of God.”

What animates us, what makes us living beings in the image of God, is that which survives the body. In Biblical Hebrew, the word that is translated in English as “soul” is “nepeŝ.” A survey of its use throughout the Hebrew Scriptures shows that there is no adequate word in English that captures its meaning. In the Genesis account of the creation of man, it means the totality of the self, both one’s spiritual and physical being. The Prophet Jeremiah shows that we can prove our nepeŝ to be righteous (3:11), that we must not try to deceive our nepeŝ (37:9), or expose our nepeŝ to evil (26:19).

It is, for the Prophet Ezekiel, the source of our capacity for empathy; “To know the nepeŝ of the stranger” is to know how it feels to be a stranger (Ezekiel 23:9). It is the subject of human attributes of the heart (Psalm 139:14, Proverbs 19:4). It is also a source of our consciousness (Esther 4:13, Proverbs 23:7). There are 317 references to it in the Hebrew Scriptures. In the New Testament, it is that which, for Mary, “magnifies the Lord” (Luke 1:46).

Of interest, in the Greek of the New Testament, “nepeŝ” is translated as “psyche.” It is the source of one’s consciousness and life. Some Scripture scholars equate the “ego” of Freudian psychology as coming closer to the meaning of nepeŝ than any other word. It is the source of one’s self, one’s identity and self-awareness. It is what remains of the immortality lost in Eden and restored in Christ. Our nepeŝ survives our death.

To believe in God and not believe in the reality of our soul is folly. Hope, the assurance of salvation, is the anchor of the soul (Hebrews 6:19). The New Testament presentation of the immortality of the soul is not a new idea, but a radically new revelation of the meaning of life and salvation illuminated by the Resurrection of Jesus.

The word, “resurrection” appears only twice in Hebrew Scripture, and both are in the Second Book of Maccabees. When Eleazar and seven brothers were being tortured to death for their fidelity to God, one of the brothers proclaimed to Antiochus the king:

“I cannot but choose to die at the hands of men and to cherish the hope that God gives of being raised again by him. But for you there will be no resurrection to life.”

That account is also referenced in the Book of Daniel (3:16-18). It was written in about 150 BC during the emergence of a Messianic Age in Judaism. The other account found in Second Maccabees also presents Biblical support for the existence of Purgatory and the Spiritual Work of Mercy to pray and atone for the dead:

“The noble Judas (Maccabeus) took up a collection … and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. In doing this, he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection … therefore he made atonement for the dead that they might be delivered from their sin.”

Almost Heaven

Despite the famous song of John Denver, Heaven is not in West Virginia. Not even almost. I take the liberty of capitalizing it because what the Hebrew Scriptures refer to as “Heaven” and “the heavens” are two different places. The heavens refer to the ancient Semitic conception of the visible Universe. God is there, but only because He is everywhere. “Heaven,” on the other hand, refers to the dwelling place of God. In modern translation, it has 575 references in Sacred Scripture as opposed to 113 for “the heavens.”

There are multiple passages in both Testaments of Scripture that refer to Heaven as the dwelling place of God, but in some, the dwelling of God is said to be in the “Heaven of Heavens,” or in “the Highest Heaven” (see Deuteronomy 10:14, 1 Kings 8:27, and Psalm 148:4). Hebrew literature was influenced by the use of the Hebrew word, “ŝamāyim” for Heaven, though it is in the plural. There are obscure references to stages or levels of Heaven. Being a Jew educated in the traditions of the Pharisees, this conception was the basis for Saint Paul’s description (2 Corinthians 12:2) that he was taken up to the Third Heaven which is identified with Paradise:

“I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third Heaven – whether in the body or out of the body, I do not know. God knows. And I know that this man was caught up into Paradise.”

I wrote of the Scriptural use of the word “Paradise” some years ago in one of the most-read posts on Beyond These Stone Walls, “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” The Greek term, “Parádeisos, came into Greek from the Akkadian term for Paradise. It is used three times in the New Testament: here, in St. Paul’s reference to Heaven; In the Book of Revelations (2:7) as the eternal dwelling that awaits the saints; and in the above-cited link referencing the Gospel of St. Luke (23:43) and his account of the words of Jesus to the criminal who comes to faith while being crucified next to Him: “Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

The same term, Parádeisos, appears in the Septuagint, the only surviving translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. The word, “Septuagint” means “seventy,” referring to the number of Greek translators of the Hebrew Bible who developed it in the Second Century B.C. It is sometimes referred to by its Roman numerals: The LXX. Back to my point, the word, “Parádeisos” makes its first Biblical appearance in Genesis 2:8. It was a reference to the original state of Eden before the Fall of Adam, a state restored to human souls on the Cross of Christ.

It is the inheritance of true discipleship, the qualities of which are described in the Judgment of the Nations (Matthew 25:31-46). One of them is that “when I was in prison you came to me.” If you are reading this, then you have fulfilled that tenet. Jesus told us that His Father’s House has many mansions. In his parting words to me, my friend, Pornchai Moontri, said that we will next meet there — and we will one day have a house there — and it will be more than 60-square feet!

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please share this post and join us in prayer for our beloved dead family and friends on All Souls Day and throughout November.

You may also wish to read and share these related posts:

The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts

Please share this post!

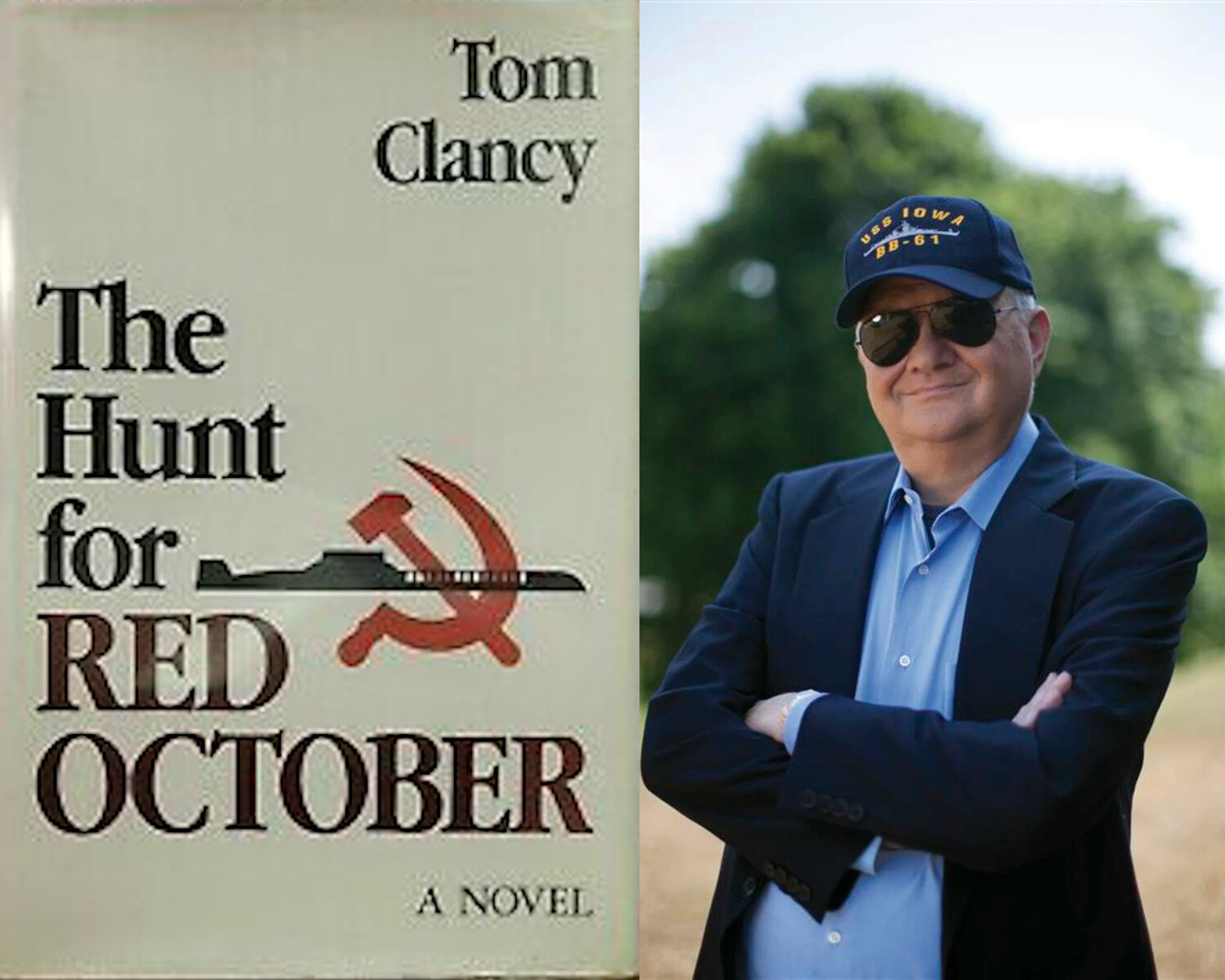

Tom Clancy, Jack Ryan, and The Hunt for Red October

Novelist Tom Clancy, master of the techno-thriller, died on October 1st. His debut Cold War novel, The Hunt for Red October, was an American literary landmark

Novelist Tom Clancy, master of the techno-thriller, died on October 1st. His debut Cold War novel, The Hunt for Red October, was an American literary landmark.

In 2011 at Beyond These Stone Walls, I wrote a post for All Souls Day entitled “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.” Some readers who have lost loved ones very dear to them found solace in its depiction of death as a continuation of all that binds human hearts and souls together in life. Like all of you, I have lost people whose departure left a great void in my life.

It’s rare that such a void is left by someone I knew only through books, but news of the death of writer, Tom Clancy at age 66 on October 1st left such a void. I cannot let All Souls Day pass without recalling the nearly three decades I’ve spent in the company of Tom Clancy.

I’ll never forget the day we “met.” It was Christmas Eve, 1984. Due to a sudden illness, I stood in for another priest at a 4:00 PM Christmas Eve Mass at Saint Bernard Parish in Keene, New Hampshire. I had no homily prepared, but the noise of a church filled with excited children and frazzled parents conspired against one anyway. So I decided in my impromptu homily to at least try to get a few points of order across.

Standing in the body of the church with a microphone in hand I began with a question: “Who can tell me why children should always be quiet and still during the homily at Mass?” One hand shot up in the front, so I held the microphone out to a little girl in the first pew. Proudly standing up, she put her finger to her lips and whispered loudly into the mic, “BECAUSE PEOPLE ARE SLEEPIN’!”

Of course, it brought the house down and earned that little girl — who today would be about 38 years old — a rousing round of applause from the parishioners of Saint Bernard’s. It lessened the tension a bit from what had been a tough year for me in that parish.

But that’s not really the moment I’ll never forget. After that Mass, a teenager from the parish walked into the Sacristy to hand me a hastily wrapped gift. In fact, it looked as though he wrapped it during the homily! “We’re not ALL sleeping,” he said about the little girl’s remark. I laughed, and when it was clear that he wasn’t leaving in any hurry, I asked whether he wanted me to open his gift. He did. I joked about needing bolt cutters to get through all the tape. It was a book. It was Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October. “Oh, wow!” I said. “How did you know I’ve been wanting to read this?”

It was a lie. I admit it. But it was a white lie. It was the sort of lie one tells to spare the feelings of someone who gives you a book you’ve never heard of and had no plan to read. I remember hearing about a circa 1980 interview of Barbara Walters with “Miss Lillian,” a Grand Dame of the U.S. South and the mother of then President Jimmy Carter. Miss Lillian — to the chagrin of presidential handlers — declared that her son, the President, “has nevah told a lie.”

“Never?!” prodded Barbara Walters. “Well, perhaps just a white lie,” Miss Lillian hastily added. “Can you give us an example of a white lie?” asked Barbara Walters. After a thoughtful pause, Miss Lillian looked her in the eye and reportedly said in her pronounced Southern drawl, “Do you remembah backstage when Ah said you look really naace in thaat dress?” Barbara was speechless! First time ever!

Mine was that sort of lie. The young giver of that gift would be about 43 years old today, and if he is reading this I want to apologize for my white lie. Then I also want to tell him that his gift changed the course of my life with books. I had read somewhere that First Lady Nancy Reagan also gave that book as a gift that Christmas. True to his penchant for adding new words to the modern American English lexicon, President Ronald Reagan declared The Hunt for Red October to be “unputdownable!”

So after a few weeks collecting dust on my office bookshelf I took The Hunt for Red October down from the shelf and opened its pages late one winter night.

“Who the Hell Cleared This?”

After busy days I have a habit of reading late at night, a habit that began almost 30 years ago with this gift of Tom Clancy’s first novel. Parishioners commented that they drove down Keene’s Main Street at night to see the lights on in my office, and “poor Father burning midnight oil at his desk.” I was doing nothing of the sort. I was submersed in The Hunt for Red October, at sea in an astonishing story of courage and patriotism.

In the early 1980s, the Cold War was freezing over again. The race to develop a “Star Wars” defense against nuclear Armageddon dominated the news. President Ronald Reagan had thrown down the gauntlet, calling the Soviet Union an “Evil Empire.” Pope John Paul II was working diligently to dismantle the Soviet machine in Poland. The Soviet KGB was suspected of being behind an almost deadly attempt to assassinate the pope. It was an event that later formed yet another powerful and stunning — and ultimately true — Tom Clancy/Jack Ryan thriller, Red Rabbit.

In the midst of this glacial stand-off between superpowers that peaked in 1984, Tom Clancy published The Hunt for Red October. Its plot gripped me from page one. The Soviets launched the maiden voyage of their newest, coolest Cold War weapon, a massive, silent, and virtually undetectable ballistic nuclear missile submarine called “Red October.” Before embarking, the Red October’s Captain, the secretly renegade Marko Ramius, mailed a letter to his Kremlin superiors indicating his intent to defect and hand over the prized sub’s technology and nuclear arsenal to the government of the United States.

By the time the Red October departed the Barents Sea for the North Atlantic, the entire Soviet fleet had been deployed to hunt her down and destroy her. American military intelligence knew only that the Soviets had launched a massive Naval offensive. An alarmed U.S. Naval fleet deployed to meet them in the North Atlantic, bringing Cold War paranoia to the brink of World War III and nuclear annihilation.

Having few options in the book, the Soviets fabricated to U.S. intelligence a story that they were attempting to intercept a madman, a rogue captain intent on launching a nuclear strike against America. Captain Marko Ramius and the Red October were thus hunted across the Atlantic by the combined Naval forces of the world’s two great superpowers operating in tandem, and in panic mode, but for different reasons.

Then the world met Jack Ryan, a somewhat geeky, self-effacing Irish Catholic C.I.A. analyst and historian. Ryan, with an investigator’s eye for detail, had studied Soviet Naval policies and what files could be obtained on its personnel. Jack Ryan alone concluded that Captain Marko Ramius was not heading for the U.S. to launch nuclear missiles, but to defect. Ryan had to devise a plan to thwart his own country’s Navy, and simultaneously that of the Soviet Union, to bring the defector and his massive submarine into safe harbor undetected.

In the telling of this tale, Tom Clancy nearly got himself into a world of trouble. His understanding of U.S. Navy submarine tactics and weapons technology was so intricately detailed that he was suspected of dabbling in leaked and highly classified documents. When Navy Secretary, John Lehman read the book, he famously shouted, “WHO THE HELL CLEARED THIS?”

The truth is that Tom Clancy was an insurance salesman whose handicap — his acute nearsightedness — kept him out of the Navy. He wrote The Hunt for Red October on an IBM typewriter with notes he collected from his research in the public records of military technology and history available in public libraries and published manuals. His previous writing included only a brief article or two in technical publications.

The Hunt for Red October was so accurately detailed that its publishing rights were purchased by the Naval Institute Press for $5,000. Clancy hoped that it might sell enough copies to cover what he was paid for it. It became the Naval Institute’s first and only published novel, and then it became a phenomenal best seller — thanks in part to President Reagan’s declaration that it was “unputdownable.” And it was! It was also — at 387 pages — the smallest of 23 novels yet to come in a series about Clancy’s hero — and alter ego — Jack Ryan.

The World through the Eyes of Jack Ryan

After devouring The Hunt for Red October in 1984, for the next 25 years — and nearly 17,000 pages of a dozen techno-thrillers — I was privileged to see the world and its political history through the eyes of Tom Clancy’s great protagonist, Jack Ryan.

From that submarine hunt through the North Atlantic, Tom Clancy took us to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in The Cardinal of the Kremlin, the Irish Republican Army’s terrorist branches in Patriot Games, the drug cartels of Colombia in Clear and Present Danger, and the threat of domestic terrorism in The Sum of All Fears. This list goes on for another seven titles in the Jack Ryan series alone as the length of Tom Clancy’s stories grew book by book to the 1,028-page tome, The Bear and the Dragon, all published by Putnam. I wrote of Tom Clancy again, and of his gift for analyzing and predicting world events, in one of the most important posts on BTSW, “Hitler’s Pope, Nazi Crimes, and The New York Times.”

At the time of Tom Clancy’s death at age 66 on October 1st, he had amassed a literary franchise with 100 million books in print, seven titles that rose to number one on best seller lists, $787 million in box office revenues for film adaptations, and five films featuring his main character, Jack Ryan, successively portrayed by Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck, and Chris Pine (the latter, and his final book, due out in December 2013).

I once made the chauvinistic mistake of calling Tom Clancy’s novels “guy books.” Mea culpa! It isn’t so, and I was divested of that view by several women I know who love his books. Writing in USA Today (“Tom Clancy wrote America well,” October 9) Laura Kenna wrote of Tom Clancy’s sure-footed patriotism as America stood firm against the multitude of clear and present dangers:

“We will miss Tom Clancy, his page-turning prose and the obsessive attention to detail that brought the texture of reality to his books. We have already been missing the political universe from which Clancy came and to which his books promised to transport us, a place never simple, but still certain, where clear convictions made flawed Americans into heroes.”

Tom Clancy was himself a flawed American hero whose nearsighted handicap was in stark contrast to the clarity and certainty of vision that he gave to Jack Ryan, and to America. I think, today, Clancy might write of a new Cold War, not the one about nuclear warheads pointing at America, but the one about Americans pointing at each other. He might today write of a nation grown heavy and weary with debt and entitlement.

As Tom Clancy slipped from this world on October 1, 2013, his country submerged itself into a sea of darker, murkier politics, those of a nation still naively singing the Blues while the Red October slips quietly away.

The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts

The concept of Purgatory is repugnant to those who do not understand Scripture, and a source of fear for many who do, but beyond the Cross, it is a source of hope.

The concept of Purgatory is repugnant to those who do not understand Scripture, and a source of fear for many who do, but beyond the Cross, it is a source of hope.

All Souls Day

Twenty-four hours after this is posted, it will no longer be All Souls Day. I risk losing everyone’s interest as we all move on to the daily grind of living. But I am not at all concerned. We’re also in the daily grind of dying. Death is all around us — it’s all around me, at least — and never far from conscious concern. Death was part of the daily prayer of Saint Padre Pio as well:

“Stay with me, Lord, for it is getting late; the days are coming to a close and life is passing. Death, judgment and eternity are drawing near.”

I have never feared death. At least, I have never feared the idea of dying. It’s just the inconvenience of it that bothers me most, not knowing when or how. The very notion of leaving this world with my affairs undone or half done is appalling to me. The thought that Someone knows of that moment but won’t share this news with me makes me squirm. “You know not the day nor the hour” (Matthew 24:36) is, for me, one of the most ominous verses in all of Scripture.

But even when a lot younger, I never thought I would have to be dragged kicking and screaming out of this life and into the next one. I think it’s because I have always had a strong belief in Purgatory. It’s one of the most wonderful and hopeful tenets of the Catholic faith that salvation isn’t necessarily a black and white affair driven solely by the peaks and valleys of this life. I have never been so arrogant as to believe that my salvation is a done deal. I have also never been so self-deprecating as to believe that God waits for the extinction of both our lives and our souls.

It is the mystery of “Hesed,” the balance of justice with mercy that I wrote of in “Angelic Justice,” that is the foundation of Purgatory. In God’s great Love for us, and in His Divine Mission to preserve that part of us that is in His image and likeness — something this world cannot possibly do — God has left a loophole in the law. It’s a way for sinners who love and trust Him, and seek to know Him, to come to Him through Christ to be redeemed. The very notion of Purgatory fills me with hope, and I’m hoping for it. It’s largely because of Purgatory that I do not fear death.

All Souls Day was first observed in the Catholic Church in the monastery of Cluny in France in the year 988. It was originally about Purgatory, and not just death. The monks at Cluny set aside the day after the Feast of All Saints — which began two centuries earlier — to devote a day of prayer and giving alms to assist the souls of our loved ones in Purgatory. In the Second Book of Maccabees (12:46) Judas Maccabeus “made atonement for the dead that they might be delivered from their sin.”

Purgatory itself has, since the earliest Christian traditions, been a tenet of faith in which the souls of those who have left this world in God’s friendship are purified and made ready for the Presence of God. The Eastern and Latin churches agree that it is a place of intense suffering, and I’m looking forward to my stint.

Okay, I’ll admit that sounds a little weird. It isn’t as though thirty years in prison has conditioned me for ever more punishment. I do not find punishment to be addictive at all, especially when I did not commit the crime. The punishment of Purgatory, however, is something I know I cannot evade. The intense suffering of Purgatory is entirely a spiritual suffering, and it begins with our experience of death right here. The longing with which we sometimes agonize over the loss of those we love is but a shadow of something spiritual we have yet to share with them: The Holy Longing they must endure as they await being in the Presence of God. That Holy Longing is Purgatory. It is the delay of the beatific vision for which we were created, and that delay and its longing is a suffering greater than we can imagine.

Death, Drawing Near

Years ago, an old friend came to me after having lost his wife of sixty years. I could only imagine what this was like for him. After her funeral and burial all his relatives finally went home, and he was alone in his grief. When we met, he told me of the intensity of his suffering. My heart was broken for him, but something in his grief struck me. I asked him not to waste this suffering, but rather to see it as a part of the longing his dear wife now has as she awaits her place in the fullness of God’s Presence. I suggested that his longing for her was but a shadow of her intense longing for God and perhaps they could go through this together. I asked him to offer his daily experience of grief for the soul of his wife.

He later told me that this advice sparked something in him that made him embrace both his grief and his loss by seeing it in a new light. Every moment in those first days and weeks and months without her was an agony that he found himself offering for her and on her behalf. He said this didn’t make any of his suffering go away, but it filled him with hope and a renewed sense of purpose. It gave meaning to his suffering which would otherwise have seemed empty.

Though I could not possibly relate to his loss, I know only too well the experience of being stranded by the deaths of others. In early Advent one year, I wrote “And Death’s Dark Shadow Put to Flight.” The title was a line from the hauntingly beautiful Advent hymn, “0 Come, 0 Come Emmanuel” that we will all be hearing in a few weeks.

That post, however, was about the death of Father Michael Mack, a Servant of the Paraclete, a co-worker, and a dear friend who was murdered in the first week of Advent. It took place on December 7th. It was a senseless death — by our standards, anyway — brought upon this 60-year-old priest and good friend by Stephen A. Degraff, a young man who took Father Mike’s life for the contents of his wallet. A part of my share in his Purgatory was to pray not only for Michael Mack, but for Stephen Degraff as well.

On the evening of December 7, 2001, Father Michael Mack returned to his home after some time helping out in a remote New Mexico diocese. Saint Paul wrote that “the Day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night” (1 Thessalonians 5:2). For Father Michael, it did just that. But for me in prison 2,000 miles away, awareness of this loss took time. No one can telephone me in prison, and I can usually only be reached by mail. It turned out that Father Michael sat at a desk in his home and wrote a letter to me on the night he died — all the while oblivious to the danger lurking in a closet in that same room. Father Mike took the letter outside to his mailbox and then walked back inside and into the moment of his death.

Three days later, after prison mail call, I sat at a small table outside my cell with the letter from Father Mike in my hands. I was so glad to hear from him. As I sat there reading the letter with a smile on my face, another prisoner asked if I wanted to see the previous day’s Boston Globe. With Father Mike’s letter in my left hand, I absentmindedly turned to page two of the Globe to see a tiny headline under National News: “New Mexico priest murdered.” Father Michael Mack’s name jumped from the page, and a part of me died just there.

All the Catholic rituals through which we bid farewell and accept the reality of death in hope are denied to a prisoner. I had only that last letter describing all Father Mike’s hopes and dreams and renewed energy for a priestly ministry to other wounded priests. Then after he signed it and scribbled in a PS — “Looking forward to hearing from you” — he walked right into his death.

This wasn’t the last time such a thing happened. This is the 30th time I mark All Souls Day in prison, and the list of souls I once knew in this life — and still know — has grown longer. In “A Corner of the Veil,” I wrote of the death of my mother — imprisoned herself during three years of grueling sickness just seventy miles from this prison, but I could not see her, speak with her, or assure her in any way except through letters that could not be answered. She died November 5, 2006. Last week, I received a letter from BTSW readers Tom and JoAnn Glenn which included a beautiful photograph of my mother imprinted on a prayer card. They found the photograph on line. I had never seen it, and was so grateful that they sent this to me.

No news of death has ever come to me with more devastation than that of my friend, Father Clyde Landry. Father Mike Mack, Father Clyde, and I were co-workers and good friends, sharing office space in the years we worked in ministry to wounded priests at the Servants of the Paraclete Center in New Mexico. I was Director of Admissions and Father Clyde was Director of Aftercare. A priest of the Diocese of Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Father Clyde had a Cajun accent reminiscent of that famous Cajun television chef, Justin Wilson — “I Gar-on-TEE!”

The Dark Night of the Soul

On that night of Gethsemane when I was falsely accused and arrested, it was Father Clyde who first came to my aid, and stood by me throughout. When I was sent to prison, Father Clyde became my lifeline to the outside world. I called him every Saturday. It became a part of my routine, like clockwork. It was through Father Clyde that once a week I reached out to the outside world for news of friends and news of freedom. He held a small account for me to help with expenses such as telephone costs, food and clothing, small things that make a prisoner’s life more bearable. Most important of all, Father Clyde volunteered to be the keeper of everything of value that I owned.

By “everything of value,” I do not mean riches. I never had any. He kept the Chalice that was given to me at priesthood ordination. He kept the stoles that were made for me, and the small things that were dear to my life and priesthood.

He kept the irreplaceable photos of my parents — both gone now — and all the things that were a lifetime’s proof of my own existence. Everything that I left behind for prison hoping to one day see again was in the possession of Father Clyde.

A year after Father Michael Mack’s tragic death, I received a joyous letter from Father Clyde. He had a new life in ministry as administrator of a very busy retreat center in New Mexico, and he was looking forward to starting. He had also purchased a small home near the center in a beautiful part of Albuquerque. It was the first time in his 52 years that he had owned any home. It was a sign of the stability that he longed for, and a sign of his great love for the retreat ministry he was undertaking.

Father Clyde’s letter was very careful to include me in this transition. He had packed all my possessions and would place them in his spare room which he promised would be available to me whenever I was released from my nightmare. His letter was the last he wrote from his vacant apartment, all his boxes stacked just next to him. He wanted me to know that by the time I received his letter he would be moved and settled and ready for my call the following Saturday.

I received Father Clyde’s letter on a Friday evening, and tried to call his new number the next day. I got only a recorded message that the number was disconnected. In prison, no one can call me and I am unable to leave messages on any answering machine or voice mail. So I called another friend to ask if he would please send an e-mail message for me. My friend fired up his computer and asked, “Where’s it going?” I gave him the e-mail address and started my message.

“Hello Clyde,” I said. “I hope you are getting settled.” Instead of hearing the clicks of my friend’s keyboard, however, I heard only silence. He wasn’t typing. I asked him what was wrong, and knew instantly from his hesitation that something was very wrong.

“Oh, My God!” he said. “You don’t know!” He then told me that my friend, Father Clyde, never made it to his new home. When he did not show up for the signing appointment with his realtor, a search was underway. Father Clyde was found in his apartment on the floor next to the last box he had packed. At age 52, he had suffered a fatal heart attack.

Father Clyde had been gone three days by the time I learned this. No one could reach me. With Father Clyde’s letter in my left hand, I was stunned as my friend described all he knew of Father Clyde’s death, which wasn’t much. It would be many days before I could learn anything more.

In the weeks and months to follow, I was stranded in a way that I had never experienced before. I was not just alone in my grief. I was alone in prison, 2,000 miles from the world I knew and the only contacts I had, and my sole connection with the outside world was gone. It would be another seven years before the idea of this blog emerged, and I would once again reach out from prison to the outside world.

But for those seven years, I was stranded. On the Saturday after I learned of Fr. Clyde’s death, I recall sitting in my cell from where I could see the bank of prisoner telephones along one wall out in the dayroom, and I cried for the first time in many, many years. In the months to follow, everything that I once hoped one day to see again was lost. I do not know what became of any of Father Clyde’s things, or my own. I have come to know that this happens to many prisoners. Cut off from the world outside, our losses can be catastrophic.

But I came to know that grief is a gift, and I have offered it not only for the souls of Fathers Clyde, Mike, and Moe — and for my dear mother — but for the souls of all who touched my life, and in that offering I had something to share with them — a Holy Longing.

When I wrote “The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul,” it was about Purgatory. It was about my continued hope for the soul of Father Richard Lower, a brother priest driven to take his own life in a dark night all alone when all trust was broken and hope seemed but a distant dream. I have been where he was, and my response to his death was “There, but for the grace of God, go I.”

At the end of “The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul,” I included a portion of the “Prayer of Gerontius” by Saint John Henry Newman. It’s a beautiful verse about Purgatory that calls forth the abiding hope we have for our loved ones who have died, and also recalls that one thing we have left to share with them — a Holy Longing for their presence, and, in their company, for the Presence of God:

Softly and gently, dearly-ransomed soul,

In my most loving arms I now enfold thee,

And, o’er the penal waters, as they roll,

I poise thee, and I lower thee, and hold thee.

And carefully, I dip thee in the lake,

And thou, without a sob or a resistance,

Dost through the flood thy rapid passage take,

Sinking deep, deeper, into the dim distance.

Angels, to whom the willing task is given,

Shall tend, and nurse, and lull thee, as thou liest;

And Masses on the Earth and prayers in Heaven,

Shall aid thee at the throne of the most Highest.

Farewell, but not forever! Brother dear;

Be brave and patient on thy bed of sorrow;

Swiftly shall pass thy night of trial here,

And I will come and wake thee on the morrow.

— John Henry Cardinal Newman, Conclusion, “The Prayer of Gerontius”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading. Please share this post so that it may come before someone who is grieving. You may also wish to read these related posts linked herein:

Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed