“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Higgs Boson God Particle: All Things Visible and Invisible

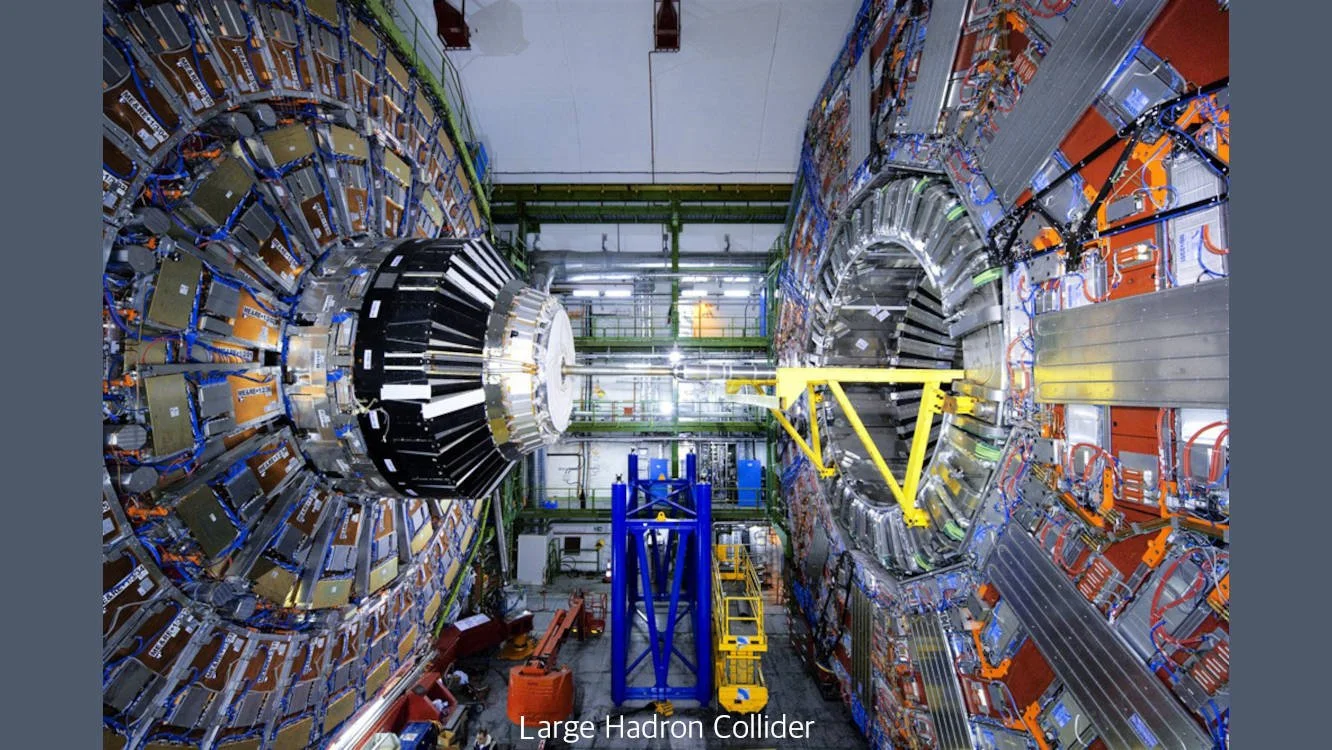

In 2012, scientists at the Large Hadron Collider detected the elusive Higgs boson, a subatomic particle dubbed the “God Particle” explaining the origin of matter.

In 2012, scientists at the Large Hadron Collider detected the elusive Higgs boson, a subatomic particle dubbed the “God Particle” explaining the origin of matter.

February 4, 2026 by Father Gordon MacRae

“Two Higgs boson particles walked into a bar. Over drinks one said, ‘I hear Stephen Hawking bet $100 that we don’t exist. What if he’s right?’ The other replied, ‘No matter!’ ”

Get it? No matter? Get it? Well, hopefully you will in a few minutes. I didn’t get it either until I did some heavy-duty reading.

If this post is creating a touch of déjà vu, a sense that you have seen it before, it’s because you probably have. Something quite unusual happened here at this blog in recent weeks. In the earliest days of this blog in 2010, I was contacted by a reader in Australia about a new book by physicists Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow entitled The Grand Design (Bantam Books, 2010). The letter writer was concerned that media outlets in Australia and around the world were citing aspects of the book out of context in an attempt to demonstrate that Stephen Hawking declared that God does not exist. That was a faulty interpretation and the reader wanted me to set the record straight. It was a tall order, but I had time on my side to ponder and present a contrary point of view. So on October 6, 2010, we published “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?”

A lot of work went into that post, but to my chagrin it was met by most of our readers with a yawn the size of a giant black hole. Fifteen years later, someone (not me) submitted that post to an advanced artificial intelligence model requesting an analysis of it. The results were then read to me by our Editor. AI scoured the Internet and then referred to me as “a Catholic priest with a background in science” while singling out that post as “a significant example of bridging the gap between science and faith.”

So of course, I thought that was the nicest thing any AI had ever said about me (There was very little to compare it to.). Given this new interest in a bridge between science and faith, I decided to haul out this 15-year-old post and rehabilitate it for a new audience. On July 30, 2025, we republished “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” The result was mind boggling, but it was not immediate. A few months later that post started showing up in our stats and then it began a viral spread. By January it was outpacing my regular weekly posts in popularity. And then by mid-January it spread all over the world in unprecedented numbers for this blog.

I cannot pretend to know why this happened. I do not understand the global attention to this one post on the space-time continuum. Perhaps my only conclusion is that when I post a bomb, just wait 15 years and post it again.

The Discovery

There is another post of mine that also bridges the gap between science and faith. I do not have an explanation for why or how, but another of my posts, this one from 2012, also began to show up in unusually large numbers with that other post. I have long wanted to repost this one with some updated information so that those who are currently reading and spreading it can see the updated version. It is “The Higgs Boson God Particle: All Things Visible and Invisible.”

I first wrote it in September 2012. It, too, was met with a rather extended yawn, but today it shows up often and everywhere. It profiles the work of the late physicist Peter Higgs who rose to prominence in the scientific community in 1964 when he theorized that the Higgs boson exists as a necessary subatomic particle which explains the existence of matter. After my post was first published, the Higgs boson was experimentally demonstrated again and Peter Higgs was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics. He died on April 8, 2024 at the age of 94 knowing that his life’s work was a major addition to the scientific understanding of the Universe.

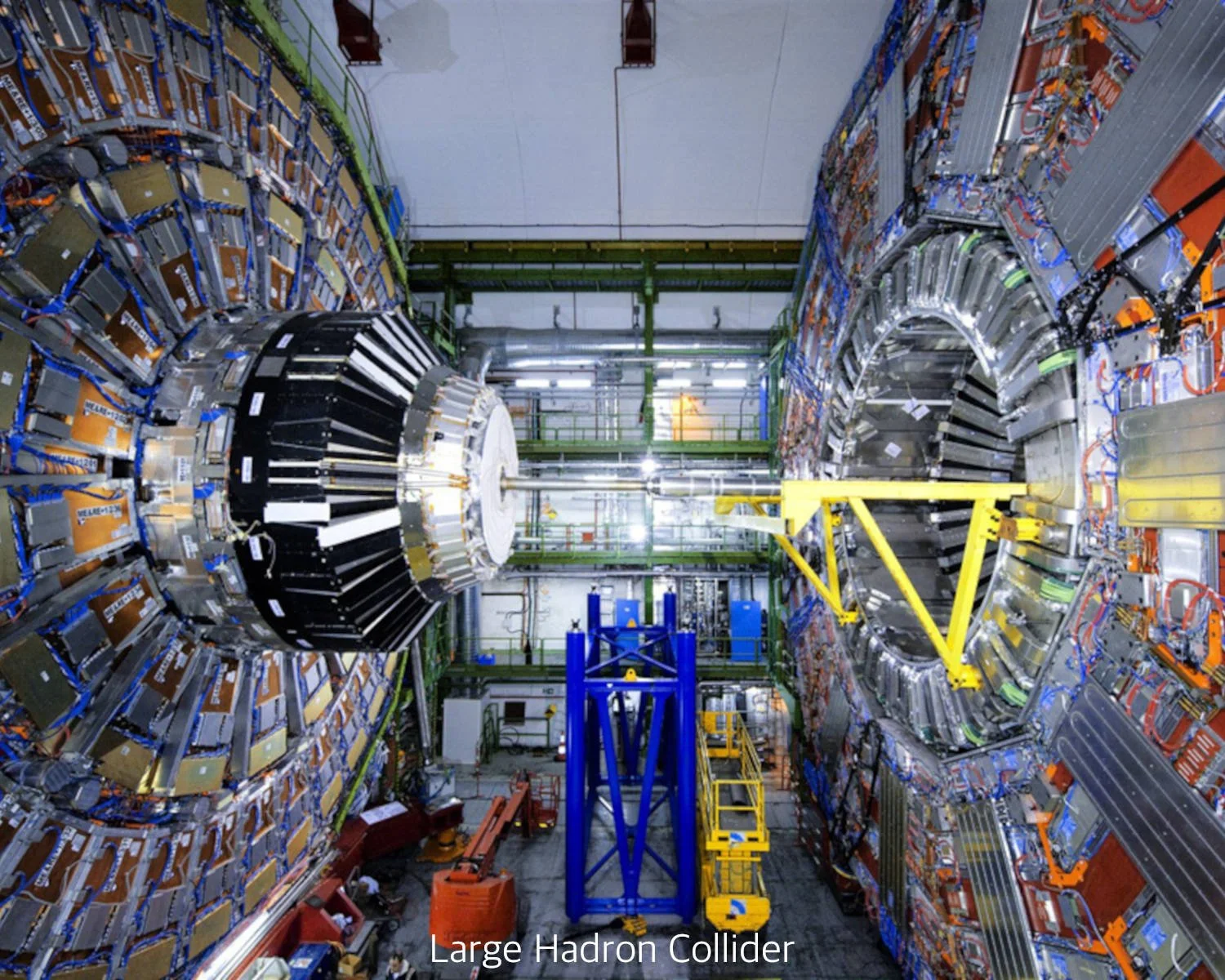

A boson in physics is a component of subatomic particles such as protons and photons, which exist in every atom of matter. As a class of particle, a boson is so-called in honor of Indian physicist, Satyenda Nath Bose, who collaborated with Albert Einstein. The existence of a then-theoretical Higgs boson resolved a puzzle in the Standard Model of physics, a widely accepted model for how particles interact. The thinking in the Standard Model was that particles such as photons — particles of light — have no mass. They should move throughout the Universe unhindered. The mathematics of the Standard Model explained successfully the existence of particles, but not mass or matter. The Higgs boson proposed by Peter Higgs in 1964 was an explanation for how particles could attain mass, and thus bring into being a Universe filled with matter that we can see or otherwise detect.

CERN, the European agency for nuclear research, operates and oversees the Large Hadron Collider. It is a donut-shaped laboratory 27-miles in circumference on the French-Swiss border. Two beams of protons were set on a collision course moving at close to the speed of light. Their collision resulted in an explosion that recreated the conditions of The Big Bang, the scientifically accepted origin of our Universe. During the collision, a supercomputer detected the presence of the Higgs boson particle and a Higgs field for a trillionth of a second. It was the first time its existence had ever been established in a laboratory

On July fourth in 2012, physicists announced that they had a momentary glimpse of the elusive Higgs boson, the subatomic particle long theorized to exist, and without which matter itself would not exist. The physicists who reported that they only found “evidence” of the Higgs boson were just being careful scientists. The discovery had a 99.9999% rate of certainty. There is no doubt left. The Higgs boson does indeed exist and that experiment has since been ratified.

So what exactly does this mean? Many scientists grimaced every time someone in the news media referred to this discovery as “the God particle.” Using science out of context to debunk religious faith is a favorite pastime of some in the media, but the reverse should also not happen.

I took a hard look at the interaction between faith and science in “Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” After publication of The Grand Design, some in the news media speculated that Hawking’s book demonstrated that gravity — and not God — is responsible for the creation of the Universe. My conclusion was simply that Stephen Hawking has thrown in with the wrong “G,” and the pundits misreading his book have confused the tools of God with God. I cited in that post a vivid example. If you were an archeologist digging in ruins in Florence, Italy and you discovered a worn chisel that was used by Michelangelo to create the Pietà, one of the most celebrated examples of sculptured marble in art history, would you then conclude that Michelangelo did not create the Pietà, his chisel did?

What I find most interesting about the recent discovery is that the Higgs boson appears nowhere in Stephen Hawking’s The Grand Design. His analysis of the science of cosmology omitted it entirely. In fact, two decades ago Stephen Hawking wagered $100 that the Higgs boson would never be detected. He lost the bet.

The discovery of the Higgs boson is a big deal in science because it presents a purely scientific explanation for how matter exists, but not why. The model for creation it implies is that a primordial atom exploded in what we call The Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago. As the explosion cooled, a force known as a “Higgs field” — which contained the Higgs boson — was formed and permeates the Universe. As other particles interacted with this field, they acquired mass allowing gravity to bring particles together. It acted sort of like a dam slowing particles so that they would mass together. The result was matter as we know and see it — everything from stars to us. It’s sort of the yeast with which God bakes bread.

A Day Without Yesterday

The Higgs boson was detected by the Large Hadron Collider’s super computers in July 2012 for a fraction of a trillionth of a second. The tiny collision sent particles in every direction producing the energy equivalent to 14 trillion electron volts and blistering temperatures. The collision recreated a tiny model of the instance of The Big Bang. Some theorize that it was the presence of the Higgs boson particle within the primordial atom that caused The Big Bang itself, and the explosion of all matter in the Universe.

I find this all fascinating, but what is most fascinating is that the entire model was first mathematically predicted, and then demonstrated to even Albert Einstein’s satisfaction, by a Catholic priest. I wrote of the Belgian priest and physicist, Father Georges Lemaitre, in “A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and the Big Bang. As a result of that post and others related to it, I began a correspondence with Father Andrew Pinsent, who prior to priesthood had been a physicist at CERN. We collaborated on a very special post, “Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang.”

If ever you bristle about the typical anti-Catholic mythology that religion attempts to hold back science, remember that the originator of all the science behind this model of creation was a Catholic priest, and many of the great scientists of his time did everything they could to suppress his ideas. They failed because they could not successfully refute either his faith or his science. In the end, even Einstein bowed to Father Lemaitre, declaring that his model was “the most satisfactory explanation of creation I have ever heard.”

Pope Pius XII applauded Father Lemaitre’s discovery of The Big Bang because it challenged the acceptable science of the time which claimed that the Universe was not created, but always existed and is eternal. Einstein later acknowledged that his “Cosmological Constant” was his greatest error.

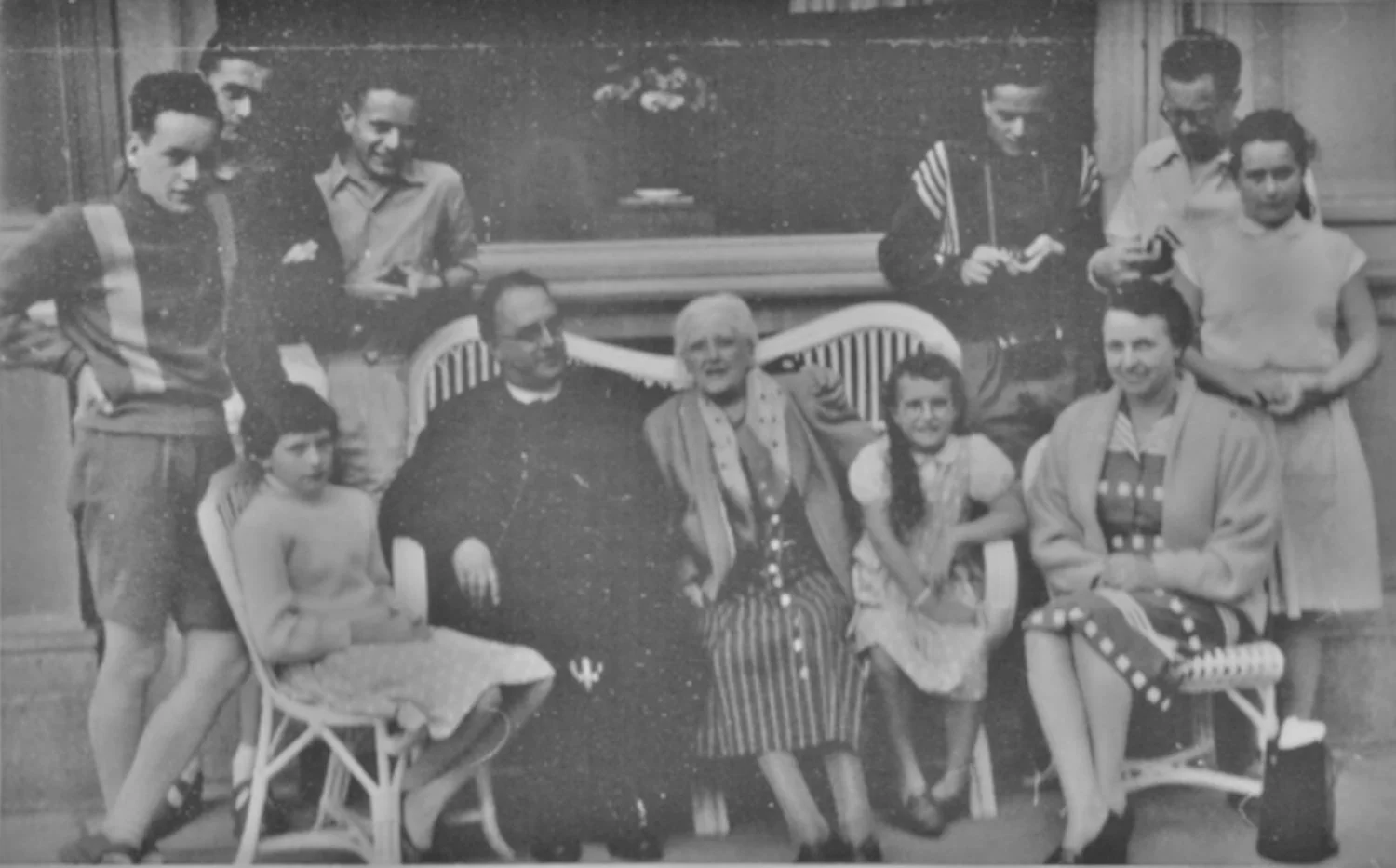

Perhaps the greatest miracle of all for me was receiving the photo below of Pornchai Moontri’s Godfather, the late Pierre Matthews, whose mother was a close friend of Father Lemaitre, who became Pierre’s Godfather. The odds that my roommate in Concord, New Hampshire would turn out to be the Godson of a man whose own Godfather discovered the Big Bang are as great as the odds of the Big Bang itself.

Michio Kaku, a professor of theoretical physics at City University of New York, wrote a brilliant and (unlike this post) brief commentary about the Higgs boson for The Wall Street Journal (“The Spark That Caused the Big Bang,” July 6, 2012). Professor Kaku wrote:

“The press has dubbed the Higgs boson the ‘God particle,’ a nickname that makes many physicists cringe. But there is some logic to it. According to the Bible, God set the Universe in motion as He proclaimed ‘Let there be light.’”

“So why did the Higgs boson particles hurry to church?

Because Mass could not start without them.”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: For open minds and enlightened souls bridges are taking shape between the realms of science and faith. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?

Fr Georges Lemaître, the Priest Who Discovered the Big Bang (a must-read by Father Andrew Pinsent)

The James Webb Space Telescope and an Encore from Hubble

For Those Who Look at the Stars and See Only Stars

+ + +

And then there was this: xAI Grok on Higgs Boson, God Particle, Science and Faith.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Did Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?

Physicist, Stephen Hawking, died on March 14, 2018. His book, The Grand Design, caused many to believe that he widened the chasm between science and faith.

Physicist, Stephen Hawking, died on March 14, 2018. His book, The Grand Design, caused many to believe that he widened the chasm between science and faith.

July 30, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

Back in 2010, in the earliest days of this blog, I wrote a post about the late, great physicist, Stephen Hawking. It was among my first posts about the dichotomy between science and faith. A controversial book, The Grand Design, published not long before I wrote about Professor Hawking, caused many to believe that he was an atheist who concluded that there is no reason to believe that God created the Universe or anything else. He attributed all of creation to one overpowering force, gravity. At the time I was pondering a response, I imagined that if I had been on an archeological dig among 15th Century ruins in Rome and found a worn chisel that was known to have belonged to Michelangelo, and used to create the Pieta, what sort of controversy would that entail? Would naysayers suggest that Michelangelo did not thus create the Pieta, his chisel did. That is the simplest response to anyone who used gravity to demonstrate that Stephen Hawking did not believe in God. God created not only the material Universe, but also all the material tools that brought the Universe into being.

Also a few weeks before I first wrote about Hawking, Pope Benedict XVI beatified John Henry Cardinal Newman in Birmingham, England. The Holy Father emphasized Cardinal Newman’s “insights into the relationship between faith and reason,” and commended him for applying “his pen to many of the most pressing subjects of the day.” Without doubt, Cardinal Newman also might have had a pointed response to the media tremors after physicist and author, Stephen Hawking declared that science can explain the creation of the Universe without God.

I mentioned Stephen Hawking in another 2010 post, “A Day Without Yesterday: Father Georges Lemaitre, and The Big Bang.” His declaration about creation came in The Grand Design. Many in the media called it a definitive statement about the existence of God. It was no such thing, but the news media cannot be accused of a lack of trying to diminish the faith of billions.

I cannot claim to have even a fraction of the gifts of faith and reason that Saint John Henry Newman would call upon to respond, but as a priest who respects science, I feel driven to weigh in. First, I have to confess that I had not by then read The Grand Design, but I eventually did. However, in a full-page article in The Wall Street Journal in 2010, Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow laid out the cosmology behind the book and their conclusions (“Why God Did Not Create the Universe,” September 4-5, 2010).

It is to that article that I here respond. If you have a concern for the implications of Professor Hawking’s pronouncement that God had nothing to do with bringing you and your world into being, please read on. There is a lot at stake here. I will address this from two points of view.

My Response as a Priest

Like Father Georges Lemaitre and Saint John Henry Newman, my response is first and foremost that of a Catholic priest. I have known many priests who have struggled with faith and some who have lost their faith. I correspond regularly with a priest who lost his faith years ago. Now this declaration by Stephen Hawking feels like a nail in faith’s coffin for him. I have lived 72 years of struggle over the question of God. I have arrived — in spite of toil, trial and tribulation, and more than my share of each — at what I think is a more than tepid faith in God’s existence and in His Grand Design. I believe in His creation of our existence. I believe in His enduring and caring Presence in this life and the promised life to come. I believe that our relationship with Him can survive this life if we walk the path He has shown to us. I wrote about that path in a recent post, “What Shall I Do to Inherit Eternal Life?”

I have read nothing in any of Stephen Hawking’s writings that causes me to wonder whether my faith conclusions are valid. I write as a priest and believer. My faith and my priesthood both came into being in a time of great social upheaval. The existential philosopher, Frederick Nietzsche (1844-1900) seemed to rule the reasoning — or lack thereof — of the 1960s. His contempt for Judaism and Christianity, and his cynical view that mankind is but a herd at the mercy of the ruling and gifted intellectual elite, marked the dawn of the “God is Dead” movement. The bumper stickers were everywhere:

“GOD IS DEAD!” Nietzsche

In the 1970s, that sorry and narcissistic wave began to dissipate, but not before destroying the faith of many who bought into it. I remember buying a bumper sticker for my seminary room door in 1978:

“NIETZSCHE IS DEAD!” God

The three masters of deceit — Freud, Marx, and Nietzsche — are all dead and not only their persons but their ideologies as well. Each reduced man to his basest, soul-less drives, and each in his own way was an enemy of faith. I do not count Stephen Hawking among them. Contrary to what the news media was lifting out of his latest book — and out of context — Stephen Hawking did not denounce God, nor does he claim to have proven that God does not exist. The exact quote that so many in the media now read into from his WSJ article cited above, and from his book is this:

“The discovery recently of extreme fine-tuning of so many laws of nature could lead some back to the idea that the grand design is the work of some grand Designer. Yet the latest advances in cosmology explain why the laws of the universe seem tailor-made for humans, without the need for a benevolent creator.”

But who would then explain the identity of the Tailor? This comes as no great revelation. One might expect that I, as a priest, would proclaim that the Universe was brought into being and maintained, at least in part for our benefit, by a Divine Creator whose title is also His name: God. But did anyone really expect Stephen Hawking, or any cosmologist to make the same declaration? What Professor Hawking has written is neither new nor surprising in cosmology. I do not, and will never have a faith that depends on science to finally and definitively weigh in on God’s existence and creation of the Universe. Science should never be able to do this to the satisfaction of any person of faith. To say that science can explain creation without God is not to say that God did not create everything — including the science and scientists trying to nudge Him from center stage. Faith is far more than the dictates of reason and the pronouncements of science. Our tradition of faith does not reduce God to His quantum mechanics, and does not promise to teach all there is to know about the created Universe or the laws of physics.

Our faith promises that we can know God through Christ in a personal relationship without fully explaining God. Who in this world can claim to fully comprehend God? Certainly not I. Faith is not an event, and science does not make or break it. Faith is a pilgrimage, and like any pilgrimage, most of us will have times of wandering, and wondering whether we will ever arrive, whether we will ever get to the point at which there are no doubts. That is the point of faith. It is its own evidence.

“Faith is the assurance of things hoped for; the conviction of things unseen”

— Hebrews 11:1

Faith at some point involves an assent of the intellect (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 155) to the revealed truth about God Himself. Central to that truth is the redemption offered to us through Christ who not only reveals God to man, but “fully reveals man to himself” (Gaudium et Spes, 22). None of us looks to Stephen Hawking, or to science, to reveal the truth about God. Faith in God and His creation can no more be subjected to the scientific method than science can legitimately be subjected and defined in the light of faith. Who among us, when faced with life’s inevitable crises, ever cried out to Stephen Hawking for mercy or for redemption?

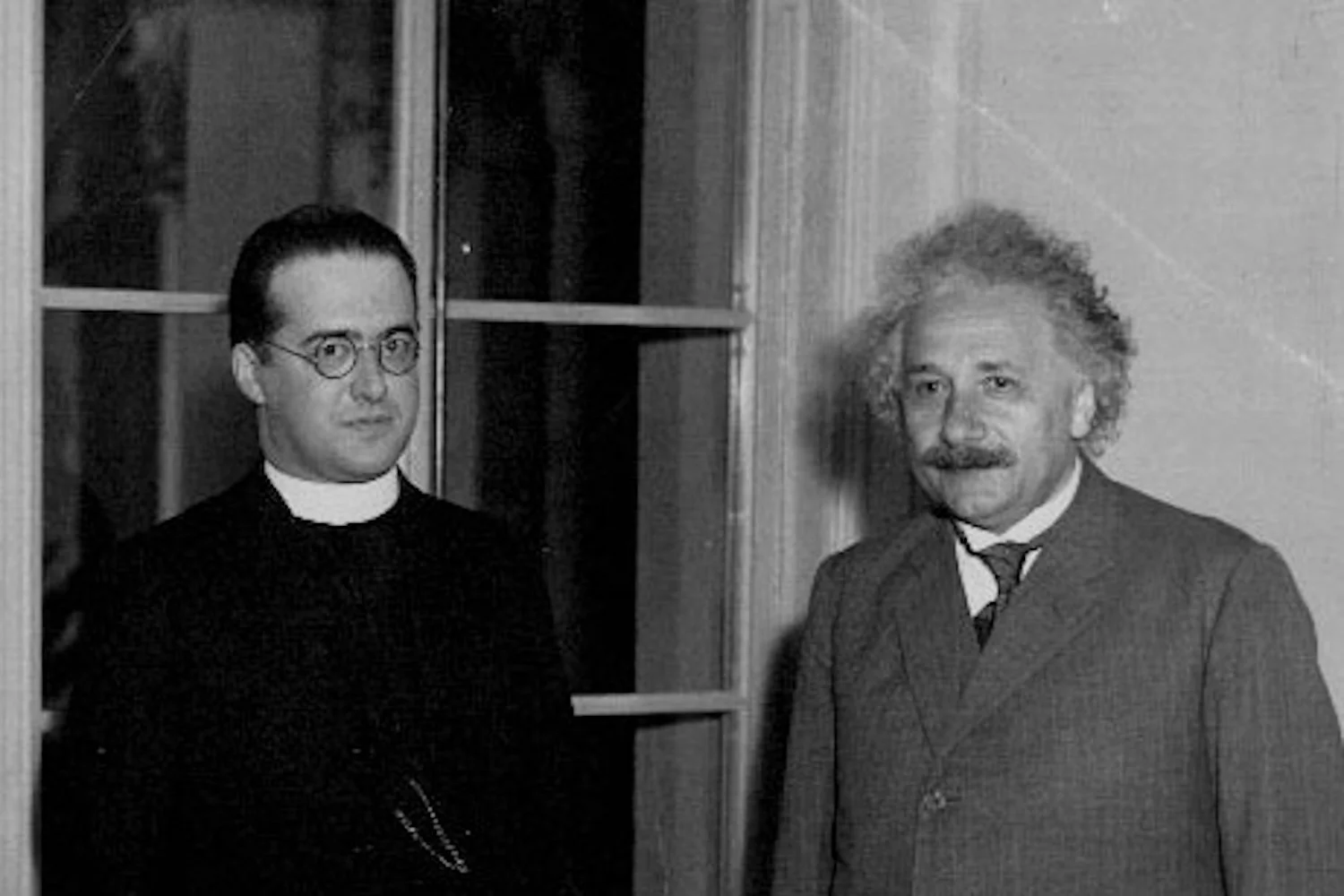

The greatest physicist of the 20th Century, Albert Einstein, never pondered God until his discussions with fellow physicist Father Georges Lemaitre. When those discussions proved to Einstein that the Universe came into being at a specific point some 13.2 Billion years earlier, Einstein responded, “I want to know God’s thoughts. The rest are just details.”

My Response as a Student of Science

I write secondly with a lifelong respect for science as a tool, not for understanding God, but for understanding the mechanics of the Universe in which we exist. This has been not so much a journey of the mind, but of the heart and soul. I at one time thought quantum mechanics referred to guys who worked on Volkswagen Beetles. To my great fortune, my mind has expanded a bit since then.

I have several times written of one of my heroes on the parallel journeys of both science and faith. One of these posts, “A Day Without Yesterday” is the story of priest, mathematician and physicist, Father Georges Lemaitre, the originator of the Big Bang explanation of cosmology and the man who changed the mind of Albert Einstein on the origin of this created Universe.

A French publication, Les Dossiers De La Recherche (No. 35, May 2009) had an interesting article entitled “Le Big Bang Histoire: De La Science A La Religion” (“The History of the Big Bang: From Science to Religion”). I am grateful to my Belgian friend, Pierre Matthews (who is also the Godfather of Pornchai Moontri). Pierre and his family knew Father Georges Lemaitre well and they translated into English this portion of the article cited above in French:

“Pope Pius XII, an enthusiastic amateur astronomer, addressed the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1951. His talk dealt with recent findings in cosmology stating: ‘It appears truly that today’s science going back millions of centuries has succeeded to witness the initial ‘fiat lux’ [Let there be light], coming out of nothing, that very moment of matter and ocean of light and rays, while the chemical components of particles split and assembled into millions of galaxies.’

“Pope Pius XII referred openly to Fr. Georges Lemaitre’s scenario. But this ‘concordism’ assumed to exist between revealed truth and science is counter-publicity for those, among them Fr. Georges Lemaitre, wanting a total and independent separation of the history of the Universe, evolution, and religious truth.

“Following a meeting with Fr. Lemaitre, Pope Pius XII a year later rejected, before the General Council of the International Astronomical Federation, any concordance between the two fields: science and faith. For Father Lemaitre, this was a double victory: cosmology can develop in total freedom and religion should no longer fear contrary positions based on new scientific discoveries.”

Why was Father Georges Lemaitre so insistent that the Pope should declare no concordance between faith and science? The obvious reason is that, for Father Lemaitre — a man of deep faith and a brilliant physicist and cosmologist — faith and science are parallel fields and should never limit each other. The Church suffered a black eye for its condemnation of Galileo’s views about science four centuries ago, but science has often seemed utterly ridiculous for holding the Church in contempt for not responding to science in 1660 as it would in 2025.

In 2005, noted science writer, Chet Raymo wrote a blog post entitled “The Future of Catholicism” on his Science Musings blog (April 10, 2005). Raymo wrote:

“In spite of the pope’s outreach to the scientific community, the Church has been slow to understand the theological implications of the scientific world view. The Church’s truce with modern cosmology and biology is uneasy at best, although certainly more enlightened than the outright rejection by fundamentalist faiths.”

Chet Raymo was right, but in a limited way. He very much understated the appreciation for scientific achievement demonstrated by the Church in the last century. We can expect this to improve greatly during the pontificate of Pope Leo XIV whose own education includes a degree in Mathematics, which leaves him well disposed to the work of Fr. George Lemaitre.

I had a brief discussion about this some years ago with a fundamentalist Evangelical pastor I know. He is an educated man, a university graduate, and well read but only very narrowly so. I asked for his opinion of what I have written above about Stephen Hawking’s views.

His response came as no surprise, and it was little different from what we might have heard from one of the Calvinist Puritan founders of New England in 1620. His view was an utter rejection of science. “The Universe was created by God in six days about 6,000 years ago. There is no such thing as poetic and metaphorical language in Scripture.” I asked him how he would explain the discoveries of bones that are many tens of millions of years old, or the fact that we can see galaxies that are millions of light years away. His answer was to simply ignore the questions. Of course, this man also believes that the Catholic Church is the anti-Christ, the “Whore of Babylon.” He believes it is not only science that is condemned, but the Catholic Church as well, and he would cite the Church’s nod to science as evidence for that view.

Science is the empirical examination of the physical Universe. Gone are the dark days in which science and religious dogma demanded conformity one with the other. There are legitimate forums for dialogue, however. It is more than ironic that Stephen Hawking was a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Science. There were calls for him to resign after he wrote The Grand Design, but I believed then that he should retain his position. Dialog should not require conformity, and the Church should not be daunted by diverse scientific views.

Using Father Georges Lemaitre’s model, Stephen Hawking should no more publicly weigh the legitimacy of Judeo-Christian belief in Creation as a design plan of God than the Pope should affirm or deny black holes. My concern for the controversy surrounding Stephen Hawking’s 2010 book is not that it encourages masses of believers to set aside their Catholic faith, as Chet Raymo declared to have done, but that it may have the effect of encouraging some Christians, Catholics among them, to set aside science. Either approach would be tragic.

Professor Hawking’s foray into the realm of faith does not change the way I perceive God. The very fact that I perceive God at all is its own evidence, “the conviction of things unseen,” (Hebrews 11:1). What it does change is my respect for the strides taken by science to speak also to the masses of people who are not scientists, but are people of faith open to science. There is a danger that science is gradually placing itself outside the experience of the great majority of people while claiming to enlighten its own elite. In this, there is a growing rift between science and the reality experienced by billions of people of faith.

The late Stephen Hawking’s view was in danger of sparking a return to the bad old days of Nietzsche, this time by the establishment of the “uber-scientist” for whom masses of faithful believers are but an ignorant herd. It is science, and not faith, that faces the greatest harm. Stephen Hawking presented that the laws of gravity, and not God, created the Universe we live in. I am not prepared to rewrite Scripture. It is not the experience of thousands of years of belief that “In the beginning, Gravity created the heavens and the earth.”

I have a response as a prisoner, too. I certainly believe in gravity, but there’s precious little solace in it, and it speaks nothing to the reality of my soul. Sorry, Professor. I respect your cosmology greatly, but I think you should not have thrown in with the wrong “G!”

I still like you, though, and I believe God does, too. He has inspired me to pray for you.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Sharing is important to place these pages before believers who may benefit from them. For 15 years we shared posts at various Catholic groups on Facebook. A few months ago Facebook called my posts “spam” and froze our account. I can no longer share there, but you can, and I thank you if you do so.

You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

“A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and The Big Bang

Science and Faith and the Big Bang Theory of Creation

Albert Einstein and Fr. George Lemaitre at the California Institute of Technology in 1930.

"I want to know God' thoughts. The rest are just details." -- Albert Einstein

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

For Fr. John Tabor, the Path to Priesthood Was War

Jaffrey, New Hampshire native Father John Tabor was called by God from the U.S. Navy at the Fall of Saigon to a half century of priesthood in Vietnam and Thailand.

Jaffrey, New Hampshire native Father John Tabor was called by God from the U.S. Navy at the Fall of Saigon to a half century of priesthood in Vietnam and Thailand.

November 30, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

Some time ago, I introduced a post by citing a famous 1990s play and movie by John Guare entitled, Six Degrees of Separation. In the film version, actor Will Smith played the central character, a young man who insinuated himself into the lives of a wealthy Manhattan couple by pretending to be the son of American actor, Sidney Poitier. The hoodwinked couple were so enthralled by what they thought was a fortuitous connection to a Hollywood star that they invited their wealthy friends to witness the new relationship. It was a con man’s dream.

The play and film introduced a theory that many came to believe was a valid sociological principle. It was the notion that the paths of all human beings are somehow connected by no more than six degrees of separation from each other. As the world grew smaller in the Internet age, the idea took on an aura of universal truth. It might even be true, for all I know, but it started off not as science, but as faith.

I have written of two examples. The path of my friend, Pornchai Moontri, my roommate of 16 years here, is separated from that of Saint Padre Pio by just two degrees. Pornchai’s Godfather, the late Pierre Matthews from Belgium, met and was blessed by Padre Pio at age 16. I wrote of their strange encounter in “With Padre Pio When the Worst that Could Happen Happens.”

Perhaps more profound and surprising, just after I wrote a popular science post about the origins of the Cosmos some years ago I learned that Pornchai is also separated by only two degrees from the famous mathematician-physicist, Fr. Georges Lemaitre, who discovered the Big Bang origin of the Universe. Father Lemaitre was a close friend of Pornchai’s Godfather’s parents who sent us several photos of them together. I wrote of the astronomical odds against such a development in “Fr. Georges Lemaitre: The Priest who Discovered the Big Bang.”

According to the theory, these two accounts left me also with only two degrees of separation from both Padre Pio and Father Lemaitre, two famous figures about whom I had been writing. It was mind-boggling, but it was never a legitimate scientific theory at all. For most people, threads of connection between people are mere coincidence. For others, they are the subtle threads of what I have called the Great Tapestry of God.

I subscribe to the latter view, but we should not try to reduce these threads to the limits of science. They are instead, for many, evidence of actual grace — perhaps more connected to a Scriptural mystery: “Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things unseen” (Hebrews 11:1). People of true faith find meaning in these connections that science overlooks.

Priesthood in a Time of War

One of these unusual threads of connection just manifested itself in my life. The November/December 2022 issue of Parable magazine, a news publication from my diocese, had as its cover story a tribute to Father John Tabor entitled, “Soldier to Servant.” My path has crossed with that of Father Tabor several times in life, but we have never actually met.

Several years older than me, John Tabor graduated from Conant High School in Jaffrey, New Hampshire in 1964. I graduated at age 16 from a Boston area high school in 1970. His path took him to the U.S. Navy and to war in Vietnam. Mine did not. I was too young at graduation to go to war, and by the time I could, the war was over.

Father Tabor’s priestly vocation was shaped by a war in which he survived several near death encounters. One of them involved a military jeep he was driving in a war zone in Da Nang. It broke down right in front of a small Catholic church where he sought the help of a local priest to repair it. A short distance down the same road on the same day, a land mine exploded that would have killed him, but John missed it because he and the priest were slow making the needed repair. It was then that John gave serious thought to something that passed only fleetingly through his mind back in high school.

In the late 18th Century, France colonized Vietnam and remained in power as an occupying force until 1954. The long French occupation of Vietnam had the unintended effect of introducing Catholicism to the Vietnamese. As a result, many Vietnamese today practice Catholic faith with great reverence. A quarter century after the French departed from Vietnam, Father John Tabor was deeply moved by the depth of Catholic faith among the people of this war-torn country.

When the war was over, and his tour of duty in the Navy ended, John Tabor wrote to his family in New Hampshire to tell them of his decision to remain in Vietnam to study for the priesthood. He immersed himself in the Vietnamese language and became fluent. Father Tabor was ordained for the Diocese of Da Nang in 1974.

In that same year half a world away, my own path to priesthood had just begun. Five years later in 1979, during theological studies at St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore, my closest friend was Tran, a Vietnamese seminarian who had been a student during the war in the seminary in Da Nang. I tutored Tran in English so he could complete his studies. Like Father Tabor, Tran, had been forced to flee Vietnam after the Fall of Saigon under the post-war oppression of the communist North Vietnamese in 1975. He brought years of war trauma with him.

Tran had been one of hundreds of thousands forced to flee Vietnam among the famous “Boat People” whose struggle for freedom and survival captured the world’s attention. During seminary studies in Baltimore, Tran often spoke to me about Father John Tabor the American priest who taught English to Vietnamese seminarians at the seminary in Da Nang where Father Tabor first ministered.

Also among the Boat People fleeing communist Vietnam was a young high school student named John Hung Le. He is known to our readers today as a heroic priest in the Missionary Society of the Divine Word and the founder of the Vietnamese Refugee Project of Thailand. He is also the priest who helped to sponsor Pornchai Moontri upon his arrival in Thailand in 2021 and continues to support his repatriation today.

The Fall of Saigon, the surrender of the South Vietnamese to Northern Communist Vietnam took place on April 30, 1975. The Viet Cong tanks and troops soon began pouring into downtown Saigon — now called Ho Chi Minh City — and spread toward Da Nang. I vividly recall news footage of waves of U.S. Marine and Air Force helicopters. They flew 6,400 military and civilian evacuees from Saigon to a 40-vessel armada waiting 15 miles off the coast of South Vietnam.

American helicopters swept into Saigon just after dawn to retrieve 30 marines from the U.S. Embassy rooftop completing the final evacuation of about 900 Americans and more than 5,000 Vietnamese. Four American marines died during the final hours of the U.S. presence in Vietnam. Two were killed in a heavy morning bombardment of Tan Son Nhut Air Base when a rocket hit the compound of the U.S. defense attache’s office where they were on guard. The other two died during the evacuation when their helicopter plunged into the South China Sea.

Several Americans, including some brave newsmen, decided to stay. Hundreds of desperate Vietnamese civilians swarmed into the U.S. embassy compound in Saigon and onto the roof after the marines had left. The roof of a nearby building also served as an emergency helipad where several hundred South Vietnamese civilians waited in hopes that there would be more helicopters to rescue them away from the coming communist oppression. They waited in vain.

Udon Thani, Thailand

Also left behind, by his own choice, was Father John Tabor who had been ordained for the Diocese of Da Nang just ten months earlier in 1974. Though now fluent in spoken and written Vietnamese, he nonetheless knew that as an American he must leave Vietnam quickly. It would not be by sea. He made his way across a border into Laos, then north to the Capital, Vientiane. From there he crossed the border into Thailand where he was canonically received into the northern Thai Diocese of Udon Thani in 1975.

For historical context for our readers, at the time Father Tabor arrived in Udon Thani, just a short distance to the south in Non Bhua Lamphu, Thailand, two-year-old Pornchai Moontri had become an orphan. That complex story was told to wide acclaim in “Bangkok to Bangor, Survivor of the Night.”

Diplomatic relations between the U.S. and the Communist government of Vietnam were not restored until 1995. Father Tabor ministered in Udon Thani, Thailand for the next 47 years. After seeing him last month on the cover of Parable in my diocese, I had a friend help me send an email message to Father John Hung Le in Thailand. I told him what I had read of the story of Father Tabor and of how he had come to New Hampshire to visit his twin brother after an absence of fifty years. I asked Father John if his path had ever crossed with that of Father Tabor who was originally from New Hampshire.

The message that came back the next day contained attachments which our editor then sent to the GTL tablet in my cell. The first was a photo of Pornchai who had been helping Father John to distribute food to Vietnamese refugee families that day. The second was the photo above of Fathers John Le and John Tabor. “We had lunch together today,” said Father John. By coincidence they met in Bangkok that very morning when Father Tabor had a required checkup upon his return to Thailand from New Hampshire.

It turned out that they are old friends whose respective paths had taken them from the terrors of war into the priesthood of Jesus Christ on the frontier of Catholic missionary service in Southeast Asia. Father John Le’s community, the Society of the Divine Word, has long had a base in Udon Thani, the most northern region of Thailand along the border with Laos very near Pornchai’s childhood home. These are heroic priests whose selfless lives have been on the front lines of service to the Lord among the poorest of the poor for decades. I am humbled to know them.

In his recent message, Father John Le told me that he and my friend, Pornchai had met that evening with Father John’s Provincial Superior on his annual visitation from the Society of the Divine Word. The connectedness of our interwoven paths is staggering. I can only make sense of it through a single line in a prayer. It is the prayer of St. John Henry Newman that I wrote about some months ago in “Divine Mercy in a Time of Spiritual Warfare.” The prayer is entitled, “Some Definite Service”:

“God has created me to do Him some definite service. He has committed some work to me which he has not committed to another. I have my mission. I may never know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next. I am a link in a chain, a bond of connection between persons.”

+ + +

Father John Tabor’s route from Da Nang, Vietnam through Laos to Udon Thani, Thailand

Note from Father Gordon MacRae:

Please keep Father John Tabor, Father John Hung Le, SVD, and Pornchai Moontri in your prayers. Over several months, readers have generously sent me gifts to be applied to Father John’s Refugee Project and the support of Pornchai’s repatriation to Thailand after 36 years. I have saved your recent gifts in support of Father John’s ministry until they amounted to $1,000 U.S.D. We just sent this amount to Father John who expressed his deeply felt gratitude (as do I!). That amount is equal to 30,000 Thai Baht which greatly assists him in bulk food and medical supply purchases for the Vietnamese refugee children and families of Thailand. During this time of global inflation, your sacrifices have made a difference. Thank you.

To assist in this project, please scroll through our SPECIAL EVENTS page for information.

Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You may also like the related links cited in this post:

Washington and the Vatican Strengthen Ties with Vietnam — National Catholic Register, October 8, 2023

“A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and The Big Bang

The Catholic Church in Belgium can take pride in the story of Georges Lemaitre, the priest and mathematician who changed the mind of Einstein on the creation of The Universe.

The Catholic Church in Belgium can take pride in the story of Georges Lemaitre, the priest and mathematician who changed the mind of Einstein on the creation of The Universe.

(This post needs a disclaimer, so here it is. It’s a post about science and one of its heroes. It’s a story I can’t tell without a heavy dose of science, so please bear with me. I read the post to my friends Pornchai, Joseph, and Skooter. Pornchai loved the math parts. Joseph said it was “very interesting,” and Skooter yawned and said, “You CAN’T print this.” When I told Charlene about the post, she said, “Well, people may never read your blog again.” Well, I sure hope that’s not the case. I happen to think this is a really cool story, so please indulge me these few minutes of science and history.)

The late Carl Sagan was a professor of astronomy at Cornell University when he wrote his 1980 book, Cosmos. It spent 77 weeks on the New York Times Best Seller List. Later in the 1980s, Dr. Sagan narrated a popular PBS series also called “Cosmos,” based on his book. Sagan was much imitated for his monotone intonation of “BILLions and BILLions of stars.” I taped all the installments of “Cosmos,” and watched each at least twice.

More than once, I fell asleep listening to Sagan’s monotone “BILLions and BILLions of stars.” I hope you’re not doing the same right now. Science was my first love as a geeky young man. Religion and faith eventually overtook it, but science never left me. Astronomy has been a lifelong fascination, and Carl Sagan was one of its icons. That’s why I was enthralled 25 years ago to walk out of a bookstore with my reserve copy of Sagan’s first and only novel, Contact (Simon & Shuster, 1985).

Contact was about radio astronomy and the SETI project — the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. It wasn’t science fiction in the way “Star Trek” was science fiction. Contact was science AND fiction, a novel crafted with real science, and no one but Carl Sagan could have pulled it off. The sheer vastness of the Cosmos unfolded with crystal clarity in Sagan’s prose, a vastness the human mind can have difficulty fathoming. Anyone who thinks we are visited by aliens from other planets doesn’t understand the vastness of it all.

The central theme of Contact was the challenge astronomy poses to religion. In the story, SETI scientist Eleanor Arroway — a wonderful character portrayed in the film version by actress Jodie Foster — becomes the first radio astronomer to detect a signal emitting from another civilization. The signal came from a planet orbiting Vega, a star, not unlike our own, about 26 light years from Earth. The message of the book (and film) is clear: if another species like us exists, and we are ever to have contact, it will be in just this way — via radio waves moving through space at light speed.

Here comes the geeky part. For those who never caught the science bug, a “light year” is a unit of distance, not time. Light moves through space at a known rate of speed — about 186,000 miles per second. At that rate, light travels through space about 5.86 trillion miles in one year. That’s a “light year,” and in numbers it represents 5,860,000,000,000 miles. In the vacuum of space, radio waves also travel at the speed of light.

The galaxy in which we live — the one we call “The Milky Way” — is a more or less flat spiral disk comprised of about 100 billion stars. The Milky Way measures about 100,000 light years across. That’s a span of about 6,000,000,000,000,000,000 miles, give or take a few. Please don’t ask me to convert this to kilometers!

This means that light — or radio waves — from across our galaxy can take up to 100,000 years to reach Earth. One of The Milky Way Galaxy’s approximately 100 billion stars is shining in my cell window at this moment. Our galaxy is one of about fifty billion galaxies now known to comprise The Universe. The largest known to us is thirteen times larger than The Milky Way. You get the picture. The Universe is immense.

If E.T. Phones Home, Make Sure It’s Collect!

In a recent post I made a cynical comment about UFOs. I wrote, “The real proof of intelligent life in The Universe is that they don’t come here.” It was an attempt at humor, but the problem with searching for extraterrestrial intelligence is one of practical physics. The limit of our ability to “listen” is a mere few hundred light years from Earth, a tiny fraction of the galaxy — a mere survey of our own backyard. If there is another civilization out there, we may never know it.

Even if we hear from them some day, it will be a one-sided conversation. The signal we may one day receive might have been broadcast hundreds — perhaps thousands — of years earlier. If we respond, it will take hundreds or thousands of years for our response to be detected. We sure won’t be trading recipes, or asking, “What’s new?” If there’s anyone out there — and so far we know of no one else — we can forget about any exchange of ideas, let alone ambassadors.

Still, I devoured Contact twice in 1985, then I wrote Carl Sagan a letter at Cornell. I understood that Sagan was an atheist, but the central story line of Contact was the effect the discovery of life elsewhere might have on religion, especially on fundamentalist Protestant sects who seemed the most threatened by the discovery.

I thought Carl Sagan handled the controversy quite well, without judgments, and even with some respect for the religious figures among his characters. In my letter, I pointed out to Dr. Sagan that Catholicism, the largest denomination of Christians in America, would not necessarily share in the anxiety such a discovery would bring to some other faiths. I wrote that if our galactic neighbors were embodied souls, like us, then they would be in need of redemption in the same manner in which we have been redeemed.

Weeks later, when an envelope from Cornell University’s Department of Astronomy and Space Sciences arrived, I was so excited my heart was beating BILLions and BILLions of times! Carl Sagan was most gracious. He wrote that my comments were very meaningful to him, and he added, “You write in the spirit of Georges Lemaitre!”

I framed that letter and put it on my rectory office wall. I wanted everyone I knew to see that Carl Sagan compared me with Georges Lemaitre! I was profoundly moved. But no one I knew had a clue who Georges Lemaitre was. I must remedy that. He was one of the enduring heroes of my life and priesthood. He still is!

Father of the Big Bang

Georges Lemaitre died on June 20, 1966 when I was 13 years old. It was the year “Star Trek” debuted on network television and I was mesmerized by space and the prospect of space travel. Georges Lemaitre was a Belgian scientist and mathematician, a pioneer in astrophysics, and the originator of what became known in science as “The Big Bang” theory — which, by the way, is no longer considered in cosmology to be a theory.

But first and foremost, Father Lemaitre was a Catholic priest. He was ordained in 1923 after earning doctorates in mathematics and science. Father Lemaitre studied Einstein’s celebrated general theory of relativity at Cambridge University, but was troubled by Einstein’s model of an always-existing, never changing universe. It was that model, widely accepted in science, that developed a wide chasm between science and the Judeo-Christian understanding of Creation. Einstein and others came to hold that The Universe had no beginning and no end, and therefore the word “Creation” could not apply.

Father Lemaitre saw problems with Einstein’s “Steady State” theory, and what Einstein called “The Cosmological Constant” in which he maintained that The Universe was relatively unchanging over time. From his chair in science at Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium from 1925 to 1931, Father Lemaitre put his formidable mind to work.

He developed both a mathematical equation and a scientific basis for what he termed the “primeval atom,” a sort of cosmic egg from which The Universe was created. He also concluded that The Universe is not static, as Einstein believed, but expanding at an ever increasing rate, and he put forward a mathematical model to prove it. In 1998, Father Lemaitre was proven to be correct.

Einstein publicly disagreed with Lemaitre’s conclusions, and the priest was not taken seriously by mainstream science largely because of that. In his book, The Universe in a Nutshell (Bantam Books, 2001), mathematician and physicist Stephen Hawking addressed the controversy:

“If galaxies are moving apart now, it means they must have been closer together in the past. About fifteen billion years ago, they would have been on top of each other, and the density would have been very large. This state was called the “primeval atom” by the Catholic priest Georges Lemaitre, who was the first to investigate the origin of the universe that we call the big bang. Einstein seems never to have taken the big bang seriously”

Stephen Hawking actually calculated the density of Father Lemaitre’s “Primeval Atom” just prior to The Big Bang. It was 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, tons per square inch. I haven’t checked this math myself, so we’ll take Professor Hawking’s word for it.

Though Einstein disagreed with Father Lemaitre at first, he respected his brilliant mathematical mind. When Einstein presented his theories to a packed audience of scientists in Brussels in 1933, he was asked if he thought his ideas were understood by everyone present. “By Professor D, perhaps,” Einstein replied, “And certainly by Lemaitre, as for the rest, I don’t think so.”

When Father Lemaitre presented his concepts of the “primeval atom” and an expanding universe, Einstein told him, “Your mathematics is perfect, but your grasp of physics is abominable.”

They were words Einstein would one day have to take back. When Edwin Hubble and other astronomers read Father Lemaitre’s paper, they became convinced that it was Einstein’s physics that was flawed. They could only conclude that the priest and scientist was correct about the creation and expansion of The Universe from the “primeval atom,” and the fact that time, space and matter actually did begin at a moment of creation, and that The Universe will end.

It’s an ironic twist that science often accuses religion of holding back the truth about science. In the case of Father Lemaitre and The Big Bang, it was science that refused to believe the evident truth that a Catholic priest proposed to a mathematical certainty: that the true origin of The Universe, and of time and space, is its creation on “a day without yesterday.”

For his work, Father Lemaitre was inducted into the Royal Academy of Belgium, and was awarded the Franqui prize by an international commission of scientists. Pope Pius XI applauded Father Lemaitre’s view of the creation of the universe and appointed him to the Pontifical Academy of Science. Later, Pope Pius XII declared that Father Lemaitre’s work was a vindication of the Biblical account of creation.

The Pope saw in Father Lemaitre’s brilliance a scientific model of a created Universe that bridged science and faith and halted the growing sense that each must entirely reject the other.

Einstein finally came around to endorse, if not openly embrace Father Lemaitre’s conclusions. He admitted that his concept of an eternal, unchanging universe was an error. “The Cosmological Constant was my greatest mistake,” he said.

In January, 1933, Father Georges Lemaitre traveled to California to present a series of seminars. When Father Lemaitre finished his lecture on the nature and origin of The Universe, a man in the back stood and applauded, and said, “This is the most beautiful and satisfying explanation of creation to which I have ever listened.” Everyone present knew that voice. It was Albert Einstein, and he actually said the “C” word so disdained by the science of his time: “Creation!”

“I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know God’s thoughts; the rest are details.”

“The more we know of the universe, the more profoundly we are struck by a Reason whose ways we can only contemplate with astonishment” … Albert Einstein once said that in the laws of nature, ‘there is revealed such a superior Reason that everything significant which has arisen out of human thought and arrangement is, in comparison with it, the merest empty reflection.’ In what is most vast, in the world of heavenly bodies, we see revealed a powerful Reason that holds the world together.”

“In the Beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters.”

“Live long and prosper.”

For Further Reading: