“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

My Father’s House Has Many Rooms. Is There a Room for Latin Mass?

In Traditionis Custodes, Pope Francis dealt a sharp but not fatal blow to Catholics who treasure the TLM. I hear from many who hope and pray for reconsideration.

In Traditionis Custodes, Pope Francis dealt a sharp but not fatal blow to Catholics who treasure the TLM. I hear from many who hope and pray for reconsideration.

In the photo above His Holiness Pope John Paul II offers Mass in Latin, ad orientem, from the Sistine Chapel.

August 20, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

My title for this post is from the Gospel of John, Chapter 14, verse 2, “My Father’s House Has Many Rooms.” It is seen by scholars as a reference to the Jerusalem Temple, hinting of its heavenly sanctuary, the dwelling place of angels and saints who worship in eternal liturgy. The Letter to the Hebrews describes it:

“You have come to Mount Zion, to the City of the Living God in the heavenly Jerusalem, to choirs of angels in festal gathering and the assembly of the firstborn enrolled in heaven, to a judge who is God of all, and to the spirits of the just made perfect, and to Jesus, mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks more graciously than the blood of Abel.”

— Hebrews 12:22-24

The Gospel passage from John 14:2 speaks of God’s House having many chambers. Could one of them accommodate the Latin Mass? In 1947, Pope Pius XII wrote in Mediator Dei, his encyclical on the liturgy, that “the mystery of the most Holy Eucharist which Christ, the High Priest, instituted and commands to be continually renewed, is the culmination and center of the Christian religion.” In the Mass the redemptive action of the death and Resurrection of Jesus is made actually present to the faithful across the centuries. This mystery of faith, the Mysterium Fidei, is found in the liturgy of the entire Church, both East and West.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC 889) tells us that “By a supernatural sense of faith” the whole People of God, under the guidance of the Church’s Magisterium, “unfailingly adheres to this faith.” To comprehend how the whole people of God is infallible in its sense of the faith — its sensus fidelium — it must be understood that the body of the faithful goes far beyond limits of space and time. The People of God always includes those of all past generations as well as those in the present. Those of the past are in fact the vast majority and it is easier to ascertain what they believed and practiced. It is that belief that marks the sensus fidelium pointing infallibly to truth.

I have never been a devotee of the Traditional Latin Mass. Growing up, I had nothing but the barest and most minimal exposure to our Catholic faith until my later adolescence. Then, in the 1960s, Latin in the Mass had receded and all manner of confusing experimentation took its place. I attended an inner city public high school then, and had begun to attend Mass just as Latin was disappearing. I wondered what all the agony in the garden of faith was about so I registered for Latin among my high school courses.

I took three successive years of Basic, Intermediate, and Advanced Classical Latin then. I developed a fascination with both the ancient language and the Roman Empire that flourished because of it. More than a half century later, I still recall my exposure to Latin. Endless declensions and conjugations still stream through my mind. My friend, Pornchai Moontri once suggested that I know Latin because it was my first language.

A House Divided Cannot Stand

On July 16, 2021, the Feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the late Pope Francis published Traditionis Custodes, a Pastoral Letter that placed immediate and severe restrictions on a Catholic celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass. The wound this inflicted on the spirit of Traditional Catholics, some of the most faithful among us, was also severe. Despite my own lack of experience with the Latin Mass, I wrote, not so much in protest, but in support of those who felt cast adrift. My post was “A House Divided: Cancel Culture and the Latin Mass.”

The restrictions became effective immediately, including a mandate barring newly ordained priests from celebration of the TLM and barring its celebration in any parish church. Bishops were suddenly required to first consult the Holy See before granting any exceptions to the Traditional (Extraordinary) Form of the Mass.

For expressed reasons of “unity,” Pope Francis imposed these restrictions without explanation in open contradiction of a 2014 Motu Proprio of his predecessor, Benedict XVI, who permitted celebration of the Traditional Latin Mass without preconditions and without consent from any bishop. Some of the best early reaction to this new and draconian development came from Father John Zuhlsdorf (Father Z’s Blog) in “First Reactions to Traditionis Custodes.”

His reactions inspired me and many. Father Z’s bottom line was that Catholics with devotion to the TLM should pause, take a deep breath, and adopt a wait-and-see attitude. He wrote,

“Fathers... change nothing, do nothing differently for now. It is not rational to leap around without mapping the mine field we are entering. Keep calm and carry on.

“Lay people... be temperate. Set your faces like flint. When you are on fire, it avails you nothing to run around flapping your arms. Drop and roll and be calm.

“To those of you who have put your heart and goods and hopes into supporting and building the Traditional Latin Mass, thank you. Do not for a moment despair or wonder if what you did was worth the effort, time, cost and suffering. It was worth it. It still is.”

— Father John Zuhlsdorf, July 16, 2021

I found myself cheering inside for Father Z. I am not a rebel priest and neither is he, but I would have been a rebel without a clue had I taken this on. I have never even experienced the TLM. But human nature being what it is, this edict of Pope Francis had the opposite effect from unity. Telling people that they cannot have something drew worldwide attention to it.

So I wrote back then, not so much in defense of the TLM, but in defense of the many people who told me of their grief in having it taken summarily away and without apparent just cause or dialogue. I cannot help but wonder what Pope Francis might have been thinking at Mass just days later as he listened to the First Reading on the Sixteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time on July 18, 2021. Was he at all conscious that Catholics all over the world were hearing the same rebuke from the Prophet Jeremiah that we heard that Sunday?

“Woe to the shepherds who mislead and scatter the flock of my pasture, says the Lord. Therefore, thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, against the shepherds who shepherd my people: You have scattered my sheep and driven them away. You have not cared for them, but... I myself will gather the remnant of my flock from all the lands and bring them back to their meadow... I will appoint shepherds for them who will shepherd them so that they need no longer fear and tremble, and none shall be missing, says the Lord.”

— Jeremiah 23:1-6

A Catholic Unraveling in Germany

I have been searching for a more panoramic map of the minefield Father Zuhlsdorf suggested that we were entering then, and I think I found some of its rumblings. While reading from Volume Two of the Prison Journal of George Cardinal Pell (which, for full disclosure, included five pages quoting this blog) I came upon his entry for 9 August 2019, the feast of Edith Stein, Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, that we observed this month. I wrote about her once in “Saints and Sacrifices: Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein at Auschwitz.”

Edith Stein was German by birth. In his book, Cardinal Pell advised readers to seek her intercession for the Church in Germany. Cardinal Pell quoted Cardinal Gerhard Muller, former Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith:

“The Catholic Church [in Germany] is going down. Leaders there are not aware of the real problems. [They are] self-centered and concerned primarily with sexual morality, celibacy, and women priests. They don’t speak about God, Jesus Christ, grace, the sacraments, and faith, hope, and love.”

— Prison Journal, Volume 2, p.75

It gets worse. Later in Prison Journal, Volume 2, in an entry dated 16 October 2019, Cardinal Pell wrote candidly about German Catholic fears of the possibility of schism that had been raised there. If allowed to happen, such a break would sweep much of Europe. Cardinal Pell quoted from a Catholic Culture article by Philip Lawler entitled, “Who Benefits from All This Talk of Schism?” (September 19, 2019):

“Lawler argues that Pope Francis has spoken calmly about such a prospect, saying he is not frightened by it, something Lawler believes is frightening in itself.”

— Prison Journal, Volume 2, p. 214

Cardinal Pell wrote of earlier confidence about the unlikelihood of a schism, but acknowledged that “the odds against it have shortened.” He added,

“Not surprisingly, the New York Times has been writing about the prospect of a schism by the John Paul and Benedict followers in the United States, the Gospel Catholics... . I believe Lawler’s diagnosis is correct when he points out that the topic of schism has been raised by the busiest and most aggressive defenders of Pope Francis who recognize that they cannot engineer the radical changes they want without precipitating a split in the Church. So they want orthodox Catholics to break away first, leaving [progressives] free to enact their own revolutionary agenda.”

— Prison Journal, Volume 2, pp. 214-215

It was that final sentence that I vividly recalled and revisited after hearing these new restrictions imposed by Pope Francis on the Traditional Latin Mass. Were we then witnessing the opening salvo of such a manipulated schism? Was there a move under way to antagonize conservative and traditional Catholics into breaking away?

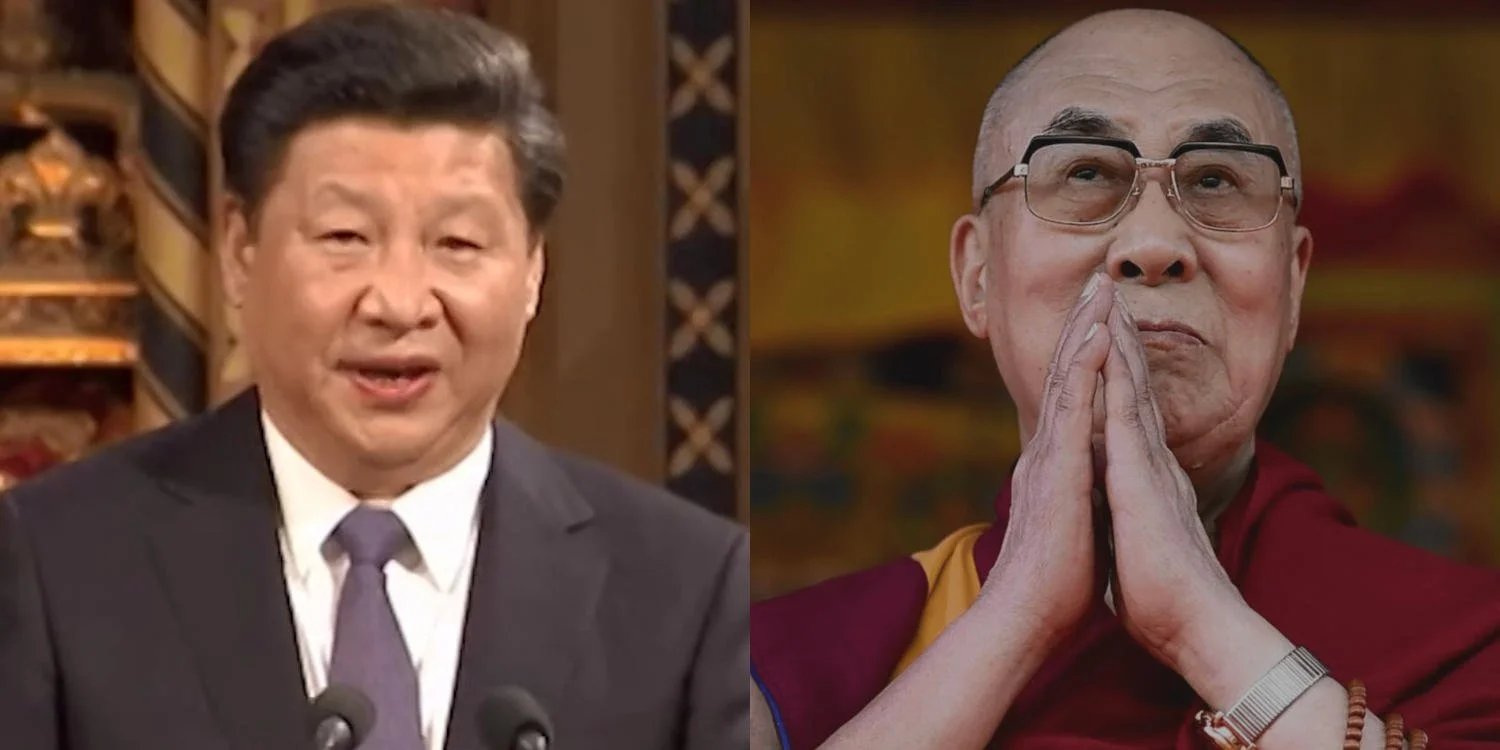

China, Catholics, and the Dalai Lama

I am certain this was not by design, but on the day after this announcement by Pope Francis, the weekend edition of The Wall Street Journal carried a stunning pair of articles. I will summarize their major points:

The first was entitled, “Beijing Targets Tibet for Assimilation” by Liza Lin, Eva Xaio, and Jonathan Cheng. The assimilation referred to is better described as suppression, and it needs a little historical background.

Twelve centuries had passed between the establishment of Tibetan Buddhism in AD 747 and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) gaining control of China in 1949. By 1950, the CCP came into increasing conflict with Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama is believed by Buddhists to be a reincarnation of the Buddha. When he dies, his soul is thought to enter the body of a newborn boy, who, after being identified by traditional tests, becomes the new Dalai Lama.

As such, the Dalai Lama is spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism and the ex officio ruler of Tibet since the Eighth Century. In 1959, during the Chinese Communist absorption of Tibet (resistance was futile!) the Dalai Lama was forced into exile in India where he has remained since. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989 for leading nonviolent opposition to continued Chinese claims to rule Tibet.

Xi Jinping, President of China and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), has as his national priority the forging of a single Chinese identity centered on unity and Party loyalty. His agenda placed new restrictions on Tibetan Buddhism and launched an effort to replace traditional Tibetan language with Mandarin Chinese while insisting on courses designed for indoctrination in socialism and the CCP.

The Dalai Lama, in exile in India, will soon turn 90 years of age. His eventual death is expected to trigger a clash with the Chinese government over control of Tibetan Buddhism. One of the major points of Chinese suppression is a CCP claim that it has the right to choose the Dalai Lama’s “reincarnation,” and thus establish full control over the heart of Tibetan religion and identity. In late 2020, President Xi Jinping commanded an effort to make Tibetan Buddhism “compatible with a socialist identity.”

This affront to Tibet’s religious freedom actually had a strange sort of precedent. In 2019, Pope Francis signed a concordat — the tenets of which are still secret — in which he agreed to a Chinese Communist Party demand to select Catholic bishops in the State-approved Chinese Catholic church. This has translated into increased harassment and suppression of the underground Catholic Church for which many have suffered for their loyalty to Rome.

The Threat of Schism

A second major article, this one by Vatican correspondent Francis X. Rocca, appeared on the same day in The Wall Street Journal, again just two days after the announced suppression of the Latin Mass. Its title asked an ominous question: “Is Pope Francis Leading the Church to a Schism?” Pope Francis had used some of the same reasoning and language in restricting the TLM that Xi Jinping used while suppressing Tibetan Buddhism. Pope Francis cited “unity” as his principal reason and goal, but its effect seemed to invite just the opposite.

Two years after Cardinal Pell wrote from his prison cell with dismal foreboding about the state of the Church in Germany, Francis X. Rocca quoted Cardinal Rainer Woelki, Archbishop of Cologne and leader of the conservative minority of German bishops. He warned that the current wave of dissent sweeping Germany could lead to schism and the formation of a German national church. Rocca reported that similar warnings have been echoed by cardinals and bishops of other European countries.

Subsequently, San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone asked for prayers for the universal Church and the bishops of Germany “that they step back from this radical rupture.” Schism is more a threat to the Catholic Church than any other because, as Rocca points out, its “core identity is inextricably tied to its global unity under the pope.”

Francis X. Rocca wrote that Pope Francis has played down the concerns of more traditional African bishops who, in the view of many represent the future of the Church’s moral integrity. For a glimpse of the mindset at work in the German church, consider this statement by Joachim Frank, a German journalist who took part in the synod there, and described its work:

“There was this sense of movement, of change, another spirit, another type of church after these boring and very painful years of John Paul II and Benedict XVI.”

In his 26-year papacy, Saint John Paul II is widely considered to have almost single-handedly brought down the Soviet Union and ended European communism. To dismiss his papacy and that of Benedict XVI as "boring and painful" is to break, not just with Catholic tradition, but with reality.

The trending Catholic mindset of Germany and much of Europe should not steer the Barque of Peter and the moral authority and praxis of the Church. In Germany, before the 2019-2021 pandemic, only about nine-percent of Catholics attended Mass on a regular basis. Post-Covid, that is now down to two or three percent. Among African Catholics, regular Mass participation is the world’s highest. By 2050, there will be twice as many practicing Catholics in Africa than in all of Europe.

Throughout Asia, Catholicism is relatively small, but growing. In Thailand, Catholics account for less than one-percent of the population but they leave a large footprint on the culture because of an orthodox commitment to living their faith, often heroically. I was recently informed by an active Catholic in Thailand that many people in his village attend the Buddhist Temple to observe local tradition, and then attend Sunday Mass to observe faith.

Our friend, Pornchai Moontri, told me that in the years he has lived in Thailand, he has heard Masses in Thai, Vietnamese, Lao, Issan, and English, all of them filled to capacity. Few of the Thai, Vietnamese, or Lao converts understand each other, nor can they understand the Mass in any language but their own. “If the Church had kept Latin,” Pornchai recently offered, “this might not happen.” He pointed out rather wisely that in the mobile culture this world has become, an ancient but universal language in the Mass promotes unity instead of detracting from it. It overlooks national identity to establish a Catholic one.

This is not meant to be a critique of Pope Francis. He had his reasons for imposing Traditionis Custodes, but new information suggests that one of them may have been based on erroneous information conveyed to him. Newly emerging information paints another picture, and I hope to present that soon. Meanwhile, please keep the faith. The Body and Blood of Christ become manifest in every Mass. That Communion is the source and summit of all grace.

“Ad Altare Dei”

+ + +

Note from Fr Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Sharing it helps to reach others who might benefit from these pages. You may also like these related posts:

Fr Gordon MacRae in the Prison Journal of George Cardinal Pell

A House Divided: Cancel Culture and the Latin Mass

Behold the Lamb of God Upon the Altar of Mount Moriah

The Vatican Today: Cardinal George Pell’s Last Gift to the Church

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Casting the First Stone: What Did Jesus Write On the Ground?

There is another scandal in the Catholic Church just under the radar. It is what happens after Father is accused, and it would never happen if he were your father.

The Woman Taken in Adultery, William Blake, c. 1805

“Teacher, this woman was caught in the act of committing adultery. In the Law, Moses commanded us to stone such women. So what do you say?,” asked the Pharisees.

March 6, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

In the three-year cycle of Scripture Readings for Catholic Mass, the Eighth Chapter of the Gospel of John (8:1-11), the story of the woman caught in adultery, is assigned to the Fifth Sunday of Lent for one of those three years. This year it is the Gospel for the day after, March 18, 2024. It is an important story and one of the most cited passages of the Gospel. It is also one of the most popularly misunderstood. Having myself been stoned in the public square, I have long been intrigued and inspired by the deeper meaning of this account.

But before we travel into the depths of that wondrous account, Holy Week is coming, and that means some in the news media are already preparing for their traditional Easter Season stoning of your faith by the hyping and re-airing of Catholic scandal. The spurious tradition in our secular news media has already begun. Not much has changed since I last wrote of our experience of this annual media stoning in a 2022 post entitled, “Benedict XVI Faced the Cruelty of a German Inquisition.” We will link to it again at the end of this post. The media’s Holy Week hot seat when I first was inspired to write it was occupied by Pope Benedict XVI. I wrote it because Pope Benedict and I had both been subjected to a stoning in the public square at about the same time.

Stoning was the most common method of execution in ancient Israel, and was seen as the community’s “purging the evil from its midst” (Deuteronomy 21:21). Stoning was imposed as both a punishment and a deterrent for a number of crimes against the community including idolatry (Deut 17:5), blasphemy (Leviticus 24: 14-16), child sacrifice (Lev 20:2), sorcery (Lev 20:27), adultery (Deut 22:13-24), and being “a stubborn and rebellious son who will not obey” (Oh, for the good old days of Deut 22:18)! That latter example reminds me of a post card I received years ago from my mother on vacation in her native Newfoundland:

“Dear Son: Newfoundland is as beautiful as I remember it. Right now I am standing at Redcliff, a 100-foot precipice where Newfoundland mothers of old would take their most troublesome sons and threaten to heave them over the edge. Wish you were here. Love, Mom.”

It is interesting that in that latter case — the stubborn and rebellious son who will not obey — the stoning was carried out by all the men of the community (Deut 21:21), and only the men. In each case, the punishment of stoning always took place outside of town. More importantly — and this has a bearing on the story of the woman caught in adultery in John 7:53-8:11 — the first stones could be cast only by firsthand witnesses of the offense. And the punishment could be imposed only when there were two or more such witnesses. “A person shall not be put to death on the evidence of only one witness” (Deut 17 6).

The Story’s Place in Scripture

The sources and limits of stoning in the Hebrew Scriptures present a necessary backdrop for a fuller understanding of John 7:53-8:11, the story of a woman caught in adultery. It’s best to let Saint John tell it:

“Jesus went to the Mount of Olives. Early in the morning he came again to the temple, all the people came to him, and he sat down and taught them. The scribes and the Pharisees brought a woman who had been caught in adultery, and placing her in their midst they said to him, ‘Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. Now, in the law, Moses commanded us to stone such. What do you say about her?’ This they said to test him, that they might have some charge to bring against him. Jesus bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. And as they continued to ask him, he stood up and said to them, ‘Let him who is without sin among you be the first to throw a stone at her.’ Again he bent down and wrote with his finger on the ground. But when they heard this they went away one by one, beginning with the eldest, and Jesus was left alone with the woman standing before him. Jesus looked up and said to her, ‘Where are they? Is there no one to condemn you?’ She said, ‘No one, Lord.’ And Jesus said, ‘Neither do I condemn you; go, and do not sin again.”

— John 7:53-8:11

The placement of this account in Scripture has endured a long controversy. The story is believed by some Scripture scholars to be an ‘agraphon,’ a source of authentic sayings of Jesus that survived orally, then became part of the written canon of Scripture toward the end of the Apostolic age. Two well known Catholic Scripture scholars — Sulpician Father Raymond Brown and Jesuit Father George W. MacRae (my late uncle) — were among those who defended that this story is both authentic and canonical despite the controversy about where it lands in the text.

The controversy itself is fascinating. It seems that some ancient versions of the Gospel of John did not contain this story, but an early text of the Gospel of Luke did. It was found in an early version of Saint Luke’s Gospel after Luke 21:38 and before Luke, Chapter 22.

“And every day he was teaching in the temple, but at night he went out and lodged on the mount called Olivet. And early in the morning, all the people came to him in the temple to hear him.”

— Luke 21:37-38

In the very next verse (Luke 22:1) the chief priests and the scribes began a conspiracy to kill Jesus. “Then Satan entered into Judas called Iscariot who was of the number of the Twelve; he went away and conferred with the chief priests how he might betray him to them. And they were glad, and engaged to give him money.” (Luke 22:3-5) So it seems that the Gospel accounts of the woman caught in adultery may have originally appeared in Scripture in the Gospel of Luke just prior to Satan entering into Judas and the plot to kill Jesus, which will be the subject of our Holy Week post this year. These accounts go to the very heart of our Catholic understanding of sin, redemption and grace.

For some scholars, the story of the woman caught in adultery may have been originally placed in between these verses. The Lord’s defeat of the nefarious intentions of the Pharisees, and his ability to use their own laws against them, may have been the trigger that set his arrest in motion. But instead this account ended up somehow in the Gospel of John, the last of the Gospel texts to come into written form at the end of the Apostolic age. Outside of Sacred Scripture, the historian, Josephus, mentions the account, but mentions it in reference to the Gospel of Saint Luke. For me, this little side road into the examination of texts and origins does not in itself question whether the text is canonical — that is, an authentic event in the life and sayings of Jesus, and an inspired Scriptural text.

For Fathers Raymond Brown and George W. MacRae (and his nephew), there is simply no reason to doubt this. But I will add one factor that the scholars may not have considered. The very idea that this story may have somehow become separated from one tradition (the Lucan tradition) only to end up in another (the Johannine tradition) is evidence of the importance of the story for the Gospel. It seems a divine determination to ensure that this story comes to us regardless of where it ended up in the Gospel narrative.

The Woman Taken in Adultery, Rembrandt, 1644 (cropped)

The Cast of Characters

The presence of the Pharisees, and their intentions in this story, call to mind a well-known parable from the Gospel of Luke, the Parable of the Good Samaritan (10:25-37). In both that account and the account of the woman caught in adultery in the Gospel of John (John 8), Jesus is confronted by a Pharisee with a question. In both cases, the purpose of the question is not to learn from Jesus, but to entrap him in a corner from which he cannot emerge. In both cases, Jesus turns the table on his questioner in a checkmate.

In the account of the woman caught in adultery above, the Pharisee seems to have laid a more solid trap. “Teacher, this woman has been caught in the act of adultery. The law of Moses commanded us to stone such. What do you say about her?” Jesus and the Pharisee both know that the Roman Empire has occupied Palestine. One of its many imposed laws is that the death penalty for crimes must be imposed and enforced only under Roman law and not under local custom. The Pharisees, therefore, could not execute the woman as the law of Moses prescribes. It is for this same reason that the High Priest, Caiaphas, had to hand Jesus, accused of blasphemy, over to the Roman governor Pontius Pilate. The prohibition is mentioned later in John:

“Pilate said to them, ‘take him yourselves and judge him by your own law.’ The Jews said to him, ‘It is not lawful for us to put any man to death.’”

— John 18:31

And so part of the trap is laid using both the Law of Moses and the politics of Rome: “This they said to test him, that they might have some charge to bring against him.” If Jesus openly concurs with the law of Moses about the penalty for adultery laid down in the Book of Deuteronomy (22:22) then the Pharisees can charge him with sedition for subverting the laws of Rome. If Jesus openly forbids the stoning, the Pharisees can use that to discredit him with his disciples as a false Messiah who contradicts the law of Moses.

The response of Jesus seems very odd. Instead of replying at all, he simply bends down and writes with his finger on the ground (John 8:6). Centuries of Scriptural wrangling have been devoted to what he could have written. What Jesus inscribed on the earth is entirely unknown, but it may well be that the act of writing on the ground — and not the content of the writing — is itself the point. What may be happening here — and some Patristic authors agree — is that Jesus uses the authority of the Prophets to undo the Pharisee’s trap using the authority of the Law. The gesture of writing on the ground may have recalled for them the Prophet Jeremiah:

“Those who turn away from you shall be written in the earth, for they have forsaken the Lord, the fountain of living water.”

— Jeremiah 17:31

Just a few verses earlier in the Gospel (John 7:38), Jesus identified himself as the fountain of living water: “He who believes in me … out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water.” Thus Jesus may well have been inscribing into the ground the very names of the Pharisees standing before him. Then Jesus did something equally odd. He stood and said, “Let him who is without sin among you be the first to cast a stone at her.” It strikes me as immense irony that the only person without sin in that gathering is Jesus himself, the one posing this counter-challenge.

This challenge of Jesus — about who is to cast the first stone at her — also recalls a law these Pharisees would know well. Deuteronomy (17:7) prohibits anyone but a firsthand witness to the crime — and there must be at least two such witnesses — from casting the first stone. So the befuddled Pharisees look at each other, wondering which of them is about to implicate himself in this adulterous offense against the law of Moses, and, if he casts the stone, implicate himself in an offense against the law of Rome.

As Jesus stooped a second time to continue his writing on the ground, the Pharisees left one by one, “beginning with the eldest.” That is another way of saying “beginning with the wisest” among them, for they were the first to catch on that their trap had not only been sprung by Jesus, but actually turned round in a way that entraps them. Once again, Jesus has exposed their duplicity and thoroughly frustrated their plans, a trend that will eventually land him before Pilate.

Thus being the sole person present without sin, and under his own terms the only one qualified to stone her, Jesus assures the woman with an act of Divine Mercy:

“‘Where are they? Has no one condemned you?’ She said, ‘No one, Lord.’ And Jesus said, ‘Neither do I condemn you; go, and do not sin again.’”

— John 8:10-11

It is the perfect Lenten story. Christ is the fountain of living water, the source of the Spirit poured out upon the world, and he is simultaneously the source of mercy poured out for those who come to know and profess the truth about Him — and about ourselves. In the very next verse in the Gospel of John, Jesus spoke to the assembled crowd as the Pharisees were departing: “I am the light of the world; he who follows me will not walk in darkness but will have the light of life.” (John 8:12)

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You might like these three related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Benedict XVI Faced the Cruelty of a German Inquisition

Stones for Pope Benedict and Rust on the Wheels of Justice

A Subtle Encore from Our Lady of Guadalupe

+ + +

An Important Announcement from His Eminence, Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke:

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Forty Years of Priesthood in the Mighty Wind of Pentecost

On the Solemnity of Pentecost Father Gordon MacRae marks forty years of priesthood. Had a map of his life been before him on June 5, 1982, what would he have done?

On the Solemnity of Pentecost Father Gordon MacRae marked forty years of priesthood. Had a map of his life been before him on June 5, 1982, what would he have done?

June 1, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

+ + +

“When you were young, you fastened your belt and walked where you would; but when you are old you will stretch out your hands and someone else will fasten them and take you where you do not wish to go.”

The Resurrected Christ to Peter (John 21:18)

+ + +

The few lines just below the top image on many blog posts are sometimes called a “meta-description.” Its purpose is to provide search engines like Google a summary of a post’s content in 164 characters or less (including spaces). Our meta-descriptions are not very useful in that regard because they are written with actual readers in mind and not search engines.

Our Editor’s meta-description atop this post ends with a question: What would I have done forty years ago on June 5, 1982 if I had before me then a vision of my future life as a priest? When I was unjustly sent to prison in 1994, I was asked that question often. I never had an easy answer.

After I began writing from prison at the invitation of Cardinal Avery Dulles fourteen years later in 2008, most people had stopped asking me that question. I think most just assumed that my life as a priest was over, or that whatever was left would just collapse and vanish under the weight of prison. Some thought the Vatican would throw me overboard without evidence simply because I am in prison. After 40 years as a priest, and 28 of them as a prisoner, none of those things has happened. I am now asked a different question: What sustains an identity of priesthood in such a place?

Also atop this post is a haunting quote from the Gospel of John (21:18). It’s from an appearance of the Risen Christ to Simon Peter and the disciples at the Sea of Tiberius. Jesus sought restitution from Peter whose courage gave way to a lie days earlier at Calvary. Peter had an opportunity to live up to his own words declared on the day before the Crucifixion, “Lord, I am ready to go with you to prison and to death.” (Luke 22:23). At Calvary, as the accusing mob pressed in, Peter’s courage failed. To appease the mob, he three times denied knowing Jesus.

I wrote in a post just weeks ago, “Shaming Benedict XVI, Catholic Schism, Cardinal Zen Arrested,” that we saw faith falter when only 92 of the world’s Catholic bishops signed a letter confronting a threat of Catholic schism in Germany while most others remained silent. We saw this again as prelates in the largest Christian denomination on Earth remained strangely silent after the Chinese Communist government’s unjust arrest of Hong Kong’s 90-year-old Joseph Cardinal Zen.

And we saw it yet again when only 15 U.S. bishops spoke out in support of San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone who courageously barred U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi from Communion until she repents for decades of abject promotion of abortion. He acted as he must in pastoral care for her soul.

But I have no legitimate judgment of Peter at Calvary. It is not easy to stand up to a mob. In the verse that immediately follows the one I quote from Saint John atop this post, the Lord told Peter what would happen when he finds his faith and it informs his strength. He did find it, and Tradition tells us that he was crucified for it in A.D. 67. The flaws of bishops, which only the spiritually blind deny sharing with them in abundance, need not preclude the courage that Christ summons forth.

An Anniversary of Priesthood

A good friend, Fr. Stuart MacDonald, just celebrated his 25th anniversary of priesthood ordination. This is usually a joyful event for a priest, for his family, and for his parish. Father Stuart sent me a wonderful photograph of the Mass of Thanksgiving at his diocesan cathedral. The recently renovated church is beautiful, and the hundreds of Father Stuart’s family, friends and parishioners could not have been prouder, or happier.

Behind the main altar in the photo above is a glorious stained glass window depicting the Crucifixion of Jesus. It is difficult to look at that sanctuary and see anything else. And yet Father Stuart stands out incensing the altar for the Liturgy of the Eucharist, his appearance one of faithful witness inspired by the salvific scene of divine restitution enacted in glory just behind him.

I pondered the scene for a long time, taking in the beauty of the restored sanctuary’s art and architecture. It is all focused on that one place where priestly hands would soon raise in sacrifice the very Lamb of God Who takes away the sins of the world — even the sins of a three times denial of Him by Peter who would then become the First Bishop of Rome.

I tend not to look at such scenes and think about myself. I was so proud of Father Stuart because he, too, has endured the suffering of the Cross in his years as a priest. Like so many, he suffered bouts of depression and anxiety during the long bludgeoning of the priesthood over the last twenty-five years. It has come from all sides, even lately from some of our bishops. Father Stuart is fortunate to have one who supports him. In an age of cancelled priests, it is not always so.

It was some time before I contrasted the photograph sent by Father Stuart with the scene in my prison cell late at night on June 5, 2022, the Solemnity of Pentecost, as I offer my own Mass of Thanksgiving for 40 years of priesthood. Able to obtain elements for Mass only once per week, I join in that sacrificial offering in a 60-square-foot prison cell in the dark. The chair upon which I offer Mass is a 5-gallon plastic trash bucket emptied and turned upside down for the occasion.

There is something vaguely prophetic in that. Like the bucket, I, too, have to be emptied before Mass of all the harmful refuse of prison. At 11:00 PM, after the last prisoner count of the day, after the last of the chaos and noise that fills this place subsides, I remove my hard-earned Mass kit from a hidden shelf in a corner. The plastic storage box relinquishes a small stole, a corporal and purificator, a sturdy plastic coffee cup. It is all I have for this purpose, but never used for any other.

Lastly comes a host and a quarter-ounce vial of sacramental wine. From a shelf at the foot of my concrete bunk comes a Sacramentary and a small battery powered book light. A concrete slab protrudes from the cinder block wall at the base of the sole, heavily barred cell window. The otherwise torturous prison lights beyond provide just enough light for Mass.

The Mass is always Ad Orientam, facing East, because that is the direction toward which my window faces. I am grateful for this despite it being of no design of my own. My little booklight illuminates the Roman Canon, the Eucharistic Prayer which affords an opportunity to name the living and the dead who accompany me in this Mass. You are always remembered there.

There is no one else physically in attendance except my non-Catholic roommate who begins snoring up a storm in his upper bunk about an hour before my Mass begins. It is not exactly the hymn of a Heavenly choir, but, like most of the harsh sounds of prison, I have learned to tune it out.

So there, sitting on my bucket — ummm, I mean the big upside-down plastic one — Heaven reaches into a place where God often seems absent, but it only seems that way. When I elevate the host for the Sacrifice of the Lamb of God, it is in equal measure just as glorious as the Cathedral altar scene where Father Stuart made that same offering. After 40 years, this may seem to some to be all that remains of the visible manifestation of my priesthood. It is a miracle in its own right, one that I described on an earlier anniversary of ordination in “Priesthood in the Real Presence, and the Present Absence.”

In the Mighty Wind of Pentecost

But there is another manifestation of priesthood less visible than my weekly offer of Mass, but just as mysterious and powerful. It has to do with the day on which my 40th anniversary of priesthood falls. It has to do with Pentecost, a Greek term meaning “fiftieth.” In Jewish tradition, it is called “Shavuot,” the Feast of Weeks. It falls on the sixth day of the Hebrew month, Savon, the concluding day of the Omer, the 49 days (seven weeks) from the Passover commanded in Leviticus (23:15-16).

In the Book of Exodus (23:16), it became the Harvest Feast. In Rabbinic legend, it was also the day Yahweh gave the Law — the Torah — to Moses on Mount Sinai in Exodus 19. It is the second of three annual feasts requiring a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. It was the reason that Mary, the Mother of Jesus, Peter, and the disciples were in Jerusalem with so many others. A seminary professor once told me that “salvation comes from the Jews. They are our spiritual ancestors, and we must honor them.” I do.

It is because they were Jews that they were in Jerusalem on the Day of Pentecost. In the Christian tradition, it is celebrated on the Seventh Sunday of Easter and closes the Easter season. Technically, it is the day after 49 days (or seven weeks) following the final Passover meal of Jesus and the Apostles, the point through which the Jewish and Christian traditions are intimately connected. It was also the day that Jesus was betrayed, the point at which Salvation History begins its fulfillment. For a deeper understanding of this, see my post, “Satan at the Last Supper, Hours of Darkness and Light.”

In the Book of Acts of the Apostles (Ch. 2), the disciples of Jesus are gathered in Jerusalem in one house: then suddenly ...

“A sound came from heaven like the rush of a mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared to them tongues as of fire, coming to rest upon each one of them. And they were filled with the Holy Spirit.”

— Acts 2: 1-4”

The scene recalls the fiery descent of the Spirit of God at Mount Sinai during the Exodus from Egypt (Exodus 19:16-19).

As that driving wind filled the room where the Apostles were gathered, “men of every race and tongue, of every people and nation” emptied into the street at the strange and powerful sound. Filled with the Holy Spirit, the Apostles began to address the bewildered crowd, each person hearing them speak in his own native tongue. In the Book of Acts, the Holy Spirit filled not only the Apostles, but some of the crowd as well, “and there were added that day about three thousand souls” (Acts 2:41).

That day in Catholic understanding is the birth of the Church, and by the time it was only an hour old, its first scandal broke out. Those in the crowd who did not inherit the wind immediately accused the Apostles of being drunk at 9:00 AM on a major holy day that required a fast. Their pharisaical claim caused Peter, now the leader of the Twelve, into the first papal defense of the Church:

“Men of Judea and all who dwell in Jerusalem, let this be known to you and give ear to my words. These men are not drunk as you suppose. It is only the third hour of the day.”

Acts 2:14-15

Inspired by the Spirit, Peter went on to preach the Church’s first homily, relying on the Prophet Joel (2:28-32) to explain that God has poured out His Spirit because the Messianic Age had begun. The meaning of the Passion of the Christ was unveiled.

It is interesting that the word for both wind and breath in Hebrew is “ruah,” and the term in Hebrew for the Holy Spirit is “ruah ha-Qodesh.” It simultaneously means the Spirit of God, the Wind of God, and the Breath of God. The same term is used in the story of Creation (Genesis 1:1-2):

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God, ‘ruah ha-Qodesh,’ was moving over the waters.”

— Genesis 1:1-2

And the term was used again in Genesis 2:7 as God breathed the Spirit into the nostrils of Adam, and yet again in a Resurrection appearance of Jesus to the Apostles, “He breathed on them and said, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit.’” (John 20:22)

The Wind of God did just as Jesus predicted it would do to Peter in the Gospel quote that began this post. It bound my hands and took me to a place where I did not wish to go. What am I to make of this? What should I have done while laying face down on the floor before an altar as the Litany of Saints offered me up in priestly sacrifice forty years ago? What would I have done then had a vision of my future life as a priest been before me?

When I look back on forty years of priesthood, most of them in exile, imprisoned souls were reached through no merit of my own. In spite of myself, the Wind of God took me up in its vortex, and I am simply blown away by it.

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Please share this post and please also visit our updated Special Events page. You may also like these related posts.

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

Priesthood in the Real Presence, and the Present Absence

Priesthood, the Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times

Satan at The Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light

The central figures present before the Sacrament for the Life of the World are Jesus on the eve of Sacrifice and Satan on the eve of battle to restore the darkness.

The central figures present before the Sacrament for the Life of the World are Jesus on the eve of Sacrifice and Satan on the eve of battle to restore the darkness.

As I begin this eleventh Holy Week post behind These Stone Walls all the world is thrust under a shroud of darkness. A highly contagious and pernicious coronavirus threatens an entire generation of the most vulnerable among us on a global scale. Many Catholics face Holy Week without the visible support and consolation of a faith community. Many of our older loved ones face it entirely alone, separated from social networks and in dread of an unknown future darkness.

A week or so before writing this, I became aware of a social media exchange between two well-meaning Catholics. One had posted a suggestion that a formula for “exorcized holy water” would repel this new viral threat. The other cautioned how very dangerous such advice could be for those who would substitute it for clear and reasoned clinical steps to protect ourselves and others. I take a middle view. All the medical advice for social distancing and prevention must be followed, but spiritual protection should not be overlooked. Satan may not be the cause of all this, but he is certainly capable of manipulating it for our hopelessness and spiritual demise.

This “down time” might be a good time to reassess where we are spiritually. A sort of “new age” culture has infiltrated our Church in the misinterpretations of the Second Vatican Council since the 1960s. There is a secularizing trend to reduce Jesus to the nice things He said in the Beatitudes and beyond to the exclusion of who He was and is, and what Jesus has done to overcome the darkest of our dark. In a recent post, I asked a somewhat overused question with its answer in the same title: “What Would Jesus Do? He Would Raise Up Lazarus — and Us.” Without that answer, faith is reduced to just a series of quotes.

By design or not I do not know, but the current darkness drew me in this holiest of weeks to a scene in the Gospel that is easy to miss. There are subtle differences in the Passion Narratives of the Gospels which actually lend credence to the accounts. They reflect the testimony of eye witnesses rather than scripts. One of these subtle variations involves the mysterious presence of Satan in the story of Holy Week.

This actually begins early in the Gospel of Luke (Ch. 4) in an account I wrote about in “To Azazel: The Fate of a Church That Wanders in the Desert.” Placed in Luke’s Gospel after the Baptism of Jesus and God’s revelation that Jesus is God’s “Beloved Son,” Jesus is led by the Spirit into the desert wilderness for forty days. He is subjected there to a series of temptations by the devil. In the end, unable to turn Jesus from his path to light, “the devil departed from him until an opportune time.” (Luke 4:13)

That opportune time comes later in Luke’s Gospel, in Chapter 22. There, just as preparations for the Passover are underway, the conspiracy to kill Jesus arises among the chief priests and scribes. They must do this in the dead of night for Jesus is surrounded by crowds in the light of day. They need someone who will reveal where Jesus goes to rest at night and how they can identify him in the darkness.

Remember, there is no artificial light. The dark of night in First Century Palestine is a blackness like no one today has ever seen. This will require someone who has been slyly and subtly groomed by Satan, someone lured by a lust for money. This is the opportune time awaited by the devil in the desert:

“Then Satan entered into Judas called Iscariot, who was of the number of the Twelve. He went away and conferred with the chief priests and the captains how he might betray him to them. And they were glad, and engaged to give him money. So he agreed and sought an opportunity to betray him to them in the absence of the multitude.”

The Hour of Darkness

In Catholic tradition, the Passion Narrative from the Gospel of John is proclaimed on Good Friday. In that account, there is a striking difference in the chronology. Satan enters Judas, not in the preparations for Passover, but later the same day, shockingly at the Table of the Lord at the Last Supper on the eve of Passover:

“So when he dipped the morsel, Jesus gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. Then, after the morsel, Satan entered into him. Jesus said to him, ‘What you are going to do, do quickly.’… So after receiving the morsel, he immediately went out, and it was night.”

Who could not be struck by those last few words, “and it was night”? They describe not only the time of day, but also the spiritual condition into which Judas has fallen. Judas and Satan are characters in this account from the Temptation of Jesus in the desert to the betrayal of Jesus in the hour of darkness. But darkness itself is also a character in this story. The word “darkness” appears 286 times in Sacred Scripture and “night” appears 365 times (which, ironically, is the exact number of nights in a year).

For their spiritual meaning, darkness and night are often used interchangeably. In St. John’s account of the betrayal by Judas, the fact that he “went out, and it was night” is highly symbolic. In the Hebrew Scriptures, our Old Testament, darkness was the element of chaos. The primeval abyss in the Genesis Creation story lay under chaos. God’s first act of creation was to dispel the darkness with the intrusion of light. “God separated the light from the darkness” (Genesis 1:4) which, in the view of Saint Augustine, was the moment Satan fell. In the Book of Job, God stores darkness in a chamber away from the path to light. God uses this imagery to challenge Job to know his place in spiritual relation to God:

“Have you, Job, commanded the dawn since your days began, and caused it to take hold of the skirts of the Earth for the wicked to be shaken out of it? … Do you know the way to the dwelling of light? Do you know the place of darkness?”

In the Book of Exodus, darkness is one of the plagues imposed upon Egypt. For the Prophet Amos (8:9) the supreme disaster is darkness at noon. In Isaiah (9:1) darkness implies defeat, captivity, oppression. It is the element of evil in which the wicked does its work (Ezekiel 8:12). It is the element of death, the grave, and the underworld (Job 10:21). In the Dead Sea Scrolls is a document called, “The Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness.” In the great Messianic Proclamation of Isaiah (9:2): “The People who walked in darkness have seen a great light.”

In the New Testament, the metaphors of light and darkness deepen. In the Gospel of Matthew (8:12, 22:13) sinners shall be cast into the darkness. In the Gospel of Mark (13:24) is the catastrophic darkness of the eschatological judgment. The Gospel of John is filled with metaphors of darkness and light. Earlier in the Gospel of John, Jesus confronts those who plot against him as under the influence of darkness and Satan:

“If God were your Father, you would love me, for I proceeded and came forth from God. I came not of my own accord, but He sent me. Why do you not understand what I say? It is because you cannot bear to hear my word. You are of your father, the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies.”

I once wrote about the person of Judas and the great mystery of his betrayal, his life, and his end in “Judas Iscariot: Who Prays for the Soul of the Betrayer?” At the Passover meal and the Table of the Lord, he dipped his morsel only to exit into the darkness. In the original story of the Passover in Exodus (13:15-18) God required the lives of the firstborn sons of Pharoah and all Egypt to deliver His people from bondage. Now, in the Hour of Darkness set in motion by Satan and Judas, God will exact from Himself that very same price, and for the very same reason.

The Hour of Light

Biblical Hebrew had no word for “hour,” nor was such a term used as a measure of time. In the Roman and Greek cultures of the New Testament, the day was divided into twelve units. The term “hour” in the New Testament does not signify a measure of time but rather an expectation of an event. The “Hour of Jesus” is prominent in the Gospel of John and also mentioned in the Synoptic Gospels. Jesus is cited in John as saying that His Hour has not yet come (7:30 and 8:20). When it does come, it is the Hour in which the Son of Man is glorified (John 12:23; 17:1).

In the Gospel of Luke (22:53), Jesus said something ominous to the chief priests and captains of the Temple who came, led by Judas (and Satan), to arrest Him: “When I was with you day after day in the Temple, you did not lay hands on me but this is your hour, and the power of darkness.”

In all of Salvation History there has never been an Hour of Darkness without an Hour of Light. In the Passion of the Christ the two were not subsequent to each other, but rather parallel, arising from the same event rooted in sacrifice. This was the ultimate thwarting of Satan’s “opportune time.” Jesus, through sacrifice, did not just defeat Satan’s plan, but used its Hour of Darkness to bring about the Hour of Light.

Amazingly, “Light” and “Darkness” each appear exactly 288 times in Sacred Scripture. It is especially difficult to separate the darkness from the light in the Passion Narratives of the Gospel. Both are necessary for our redemption. Without darkness there is no sacrifice or even a need for sacrifice.

The Hour of Light began, not at Calvary, but at the Institution of the Eucharist at The Last Supper, the Passover meal with Jesus and His Apostles. The Words of Institution of the Eucharist are remarkably alike in substance and form in each of the Synoptic Gospels and in St. Paul’s First letter to the Corinthians (11:23).

The sacrificial nature of the Words of Institution and their intent at bringing about communion with God are most prominent in the oldest to come into written form, that of Saint Paul:

“For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus, on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way also the chalice, after supper, saying, ‘This chalice is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.’ For as often as you eat this bread and drink the chalice, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.”

The enormity of this gift, the beginning of the Hour of Light, comes in the midst of words like “betrayal” and “death.” It is most interesting that the Gospel of John, which has Satan enter Judas at the Passover Table of the Lord, has no words for the formula of Institution of the Eucharist. But John clearly knows of it. The Gospel of John presents a clear theological allusion to the Eucharistic Feast in John 6:47-51:

“Truly, Truly I say to you, he who believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate manna in the desert and they died. This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if anyone eats this bread he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

The term “will live forever” appears only three times in all of Sacred Scripture: twice in the above passage from John, and once in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures in Genesis 3:22. There, God expels Adam and Eve from Eden for attempting to be like God. It is a preventive measure in Genesis “lest they eat from the Tree of Life and live forever.” For John’s Gospel, what was denied to Adam is now freely given through the Sacrifice of Christ.

It is somewhat of a mystery why the Gospel of John places so beautifully his account of the Institution of the Eucharist there in Chapter 6 just after Jesus miraculously feeds the multitude with a few loaves of bread and a few fish, and then omits the actual Words of Institution from the Passover meal, the setting for The Last Supper in each of the other Gospels and in Saint Paul’s account.

Perhaps, on a most basic level, the Apostle John, beloved of the Lord, could not bring himself to include these words of sacrifice with Satan having just left the room. At a more likely level, John implies the Eucharist theologically through the entire text of his Gospel. In the end, after a theological and prayerful discourse at table, Jesus prays for the Church:

“When Jesus had spoken these words, he lifted up his eyes to heaven and said, ‘Father, the hour has come; glorify your Son that the Son may glorify you, since you have given him power over all flesh, to give eternal life to all whom you have given him. And this is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.”

Now Comes the Hour of the Son of God, The Cross stood only for darkness and death until souls were illumined by the Cross of Christ. From the Table of the Lord, the lights stayed on in the Sanctuary Lamp of the Soul.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Take a time out from anxiety and isolation this Holy Week by spending time in the Hour of Light with these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

A Personal Holy Week Retreat at Beyond These Stone Walls

Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King But Caesar’

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

There are few things in life that a priest could hear with greater impact than what was revealed to me in a recent letter from a reader of These Stone Walls. After stumbling upon TSW several months ago, the writer began to read these pages with growing interest. Since then, she has joined many to begin the great adventure of the two most powerful spiritual movements of our time: Marian Consecration and Divine Mercy. In a recent letter she wrote, “I have been a lazy Catholic, just going through the motions, but your writing has awakened me to a greater understanding of the depths of our faith.”

I don’t think I actually have much to do with such awakenings. My writing doesn’t really awaken anyone. In fact, after typing last week’s post, I asked my friend, Pornchai Moontri to read it. He was snoring by the end of page two. I think it is more likely the subject matter that enlightens. The reader’s letter reminded me of the reading from Saint Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians read by Pornchai a few weeks ago, quoted in “De Profundis: Pornchai Moontri and the Raising of Lazarus”:

“Awake, O sleeper, and rise from the dead, and Christ will give you light.”

I may never understand exactly what These Stone Walls means to readers and how they respond. That post generated fewer comments than most, but within just hours of being posted, it was shared more than 1,000 times on Facebook and other social media.

Of 380 posts published thus far on These Stone Walls, only about ten have generated such a response in a single day. Five of them were written in just the last few months in a crucible described in “Hebrews 13:3 Writing Just This Side of the Gates of Hell.” I write in the dark. Only Christ brings light.

Saint Paul and I have only two things in common — we have both been shipwrecked, and we both wrote from prison. And it seems neither of us had any clue that what we wrote from prison would ever see the light of day, let alone the light of Christ. There is beneath every story another story that brings more light to what is on the surface. There is another story beneath my post, “De Profundis.” That title is Latin for “Out of the Depths,” the first words of Psalm 130. When I wrote it, I had no idea that Psalm 130 was the Responsorial Psalm for Mass before the Gospel account of the raising of Lazarus:

“Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord!

Lord hear my voice!

Let your ears be attentive

to my voice in supplication…

”I wait for the Lord, my soul waits,

and I hope in his word;

my soul waits for the Lord

more than sentinels wait for the dawn,

more than sentinels wait for the dawn.”

Notice that the psalmist repeats that last line. Anyone who has ever spent a night lying awake in the oppression of fear or dark depression knows the high anxiety that accompanies a long lonely wait for the first glimmer of dawn. I keep praying that Psalm — I have prayed it for years — and yet Jesus has not seen fit to fix my problems the way I want them fixed. Like Saint Paul, in the dawn’s early light I still find myself falsely accused, shipwrecked, and unjustly in prison.

Jesus also prayed the Psalms. In a mix of Hebrew and Aramaic, he cries out from the Cross, “Eli, Eli làma sabach-thàni?” It is not an accusation about the abandonment of God. It is Psalm 22, a prayer against misery and mockery, against those who view the cross we bear as evidence of God’s abandonment. It is a prayer against the use of our own suffering to mock God. It’s a Psalm of David, of whom Jesus is a descendant by adoption through Joseph:

“Eli, Eli làma sabach-thàni?

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are You so far from my plea,

from the words of my cry? …

… All who see me mock at me;

they curse me with parted lips,

they wag their heads …

Indeed many dogs surround me,

a pack of evildoers closes in upon me;

they have pierced my hands and my feet.

I can count all my bones …

They divide my garments among them;

for my clothes they cast lots.”

So maybe, like so many in this world who suffer unjustly, we have to wait in hope simply for Christ to be our light. And what comes with the light? Suffering does not always change, but its meaning does. Take it from someone who has suffered unjustly. What suffering longs for most is meaning. People of faith have to trust that there is meaning to suffering even when we cannot detect it, even as we sit and wait to hear, “Upon the Dung Heap of Job: God’s Answer to Suffering.”

The Passion of the Christ

Last year during Holy Week, two Catholic prisoners had been arguing about why the date of Easter changes from year to year. They both came up with bizarre theories, so one of them came to ask me. I explained that in the Roman Church, Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox (equinox is from the Latin, “equi noctis,” for “equal night”). The prisoner was astonished by my ignorance and said, “What BS! Easter is forty days after Ash Wednesday!”

Getting to the story beneath the one on the surface is important to understand something as profound as the events of the Passion of the Christ. You may remember from my post, “De Profundis,” that Jesus said something perplexing when he learned of the illness of Lazarus:

“This illness is not unto death; it is for the glory of God, so that the Son of God may be glorified by means of it”

The irony of this is clearer when you see that it was the raising of Lazarus that condemned Jesus to death. The High Priests were deeply offended, and the insult was an irony of Biblical proportions (no pun intended). Immediately following upon the raising of Lazarus, “the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered the council” (the Sanhedrin). They were in a panic over the signs performed by Jesus. “If he goes on like this,” they complained, “the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place (the Jerusalem Temple) and our nation” (John 11 47-48).

The two major religious schools of thought in Judaism in the time of Jesus were the Pharisees and the Sadducees. Both arose in Judaism in the Second Century B.C. and faded from history in the First Century A.D. At the time of Jesus, there were about 6,000 Pharisees. The name, “Pharisees” — Hebrew for “Separated Ones” — came as a result of their strict observance of ritual piety, and their determination to keep Judaism from being contaminated by foreign religious practices. Their hostile reaction to the raising of Lazarus had nothing to do with the raising of Lazarus, but rather with the fact that it occurred on the Sabbath which was considered a crime.

Jesus actually had some common ground with the Pharisees. They believed in angels and demons. They believed in the human soul and upheld the doctrine of resurrection from the dead and future life. Theologically, they were hostile to the Sadducees, an aristocratic priestly class that denied resurrection, the soul, angels, and any authority beyond the Torah.

Both groups appear to have their origin in a leadership vacuum that occurred in Jerusalem between the time of the Maccabees and their revolt against the Greek king Antiochus Epiphanies who desecrated the Temple in 167 B.C. It’s a story that began Lent on These Stone Walls in “Semper Fi! Forty Days of Lent Giving Up Giving Up.”

The Pharisees and Sadducees had no common ground at all except a fear that the Roman Empire would swallow up their faith and their nation. And so they came together in the Sanhedrin, the religious high court that formed in the same time period the Pharisees and Sadducees themselves had formed, in the vacuum left by the revolt that expelled Greek invaders and their desecration of the Temple in 165 B.C.

The Sanhedrin was originally composed of Sadducees, the priestly class, but as common enemies grew, the body came to include Scribes (lawyers) and Pharisees. The Pharisees and Sadducees also found common ground in their disdain for the signs and wonders of Jesus and the growth in numbers of those who came to believe in him and see him as Messiah.

The high profile raising of Lazarus became a crisis for both, but not for the same reasons. The Pharisees feared drawing the attention of Rome, but the Sadducees felt personally threatened. They denied any resurrection from the dead, and could not maintain religious influence if Jesus was going around doing just that. So Caiaphas, the High Priest, took charge at the post-Lazarus meeting of the Sanhedrin, and he challenged the Pharisees whose sole concern was for any imperial interference from the Roman Empire. Caiaphas said,

“You know nothing at all. You do not understand that it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people, so that the whole nation should not perish”

The Gospel of John went on to explain that Caiaphas, being High Priest, “did not say this of his own accord, but to prophesy” that Jesus was to die for the nation, “and not for the nation only, but, to gather into one the children of God” (John 11: 41-52). From that moment on, with Caiaphas being the first to raise it, the Sanhedrin sought a means to put Jesus to death.

Caiaphas presided over the Sanhedrin at the time of the arrest of Jesus. In the Sanhedrin’s legal system, as in our’s today, the benefit of doubt was supposed to rest with the accused, but … well … you know how that goes. The decision was made to find a reason to put Jesus to death before any legal means were devised to actually bring that about.

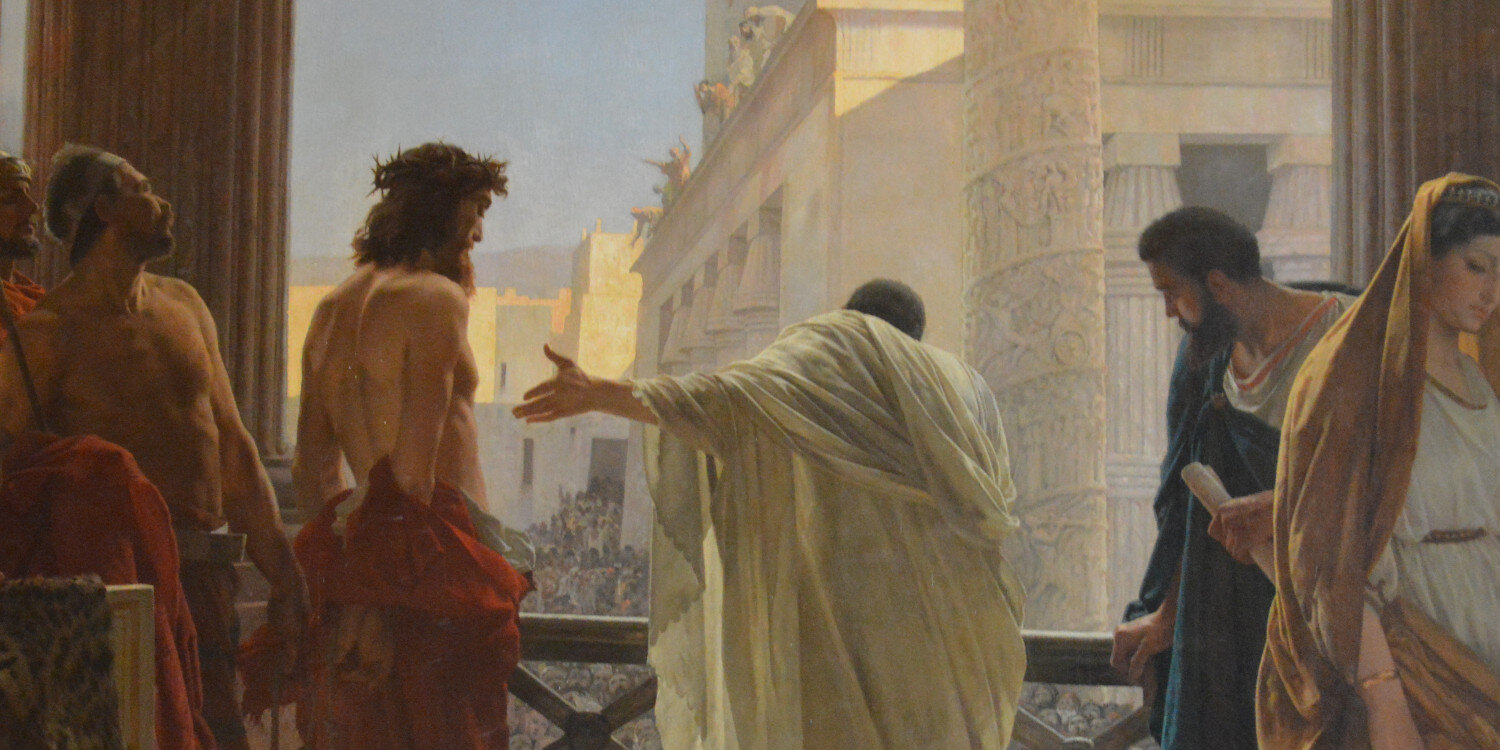

Behold the Man!

The case found its way before Pontius Pilate, the Roman Prefect of Judea from 25 to 36 A.D. Pilate had a reputation for both cruelty and indecision in legal cases before him. He had previously antagonized Jewish leaders by setting up Roman standards bearing the image of Caesar in Jerusalem, a clear violation of the Mosaic law barring graven images.

All four Evangelists emphasize that, despite his indecision about the case of Jesus, Pilate considered Jesus to be innocent. This is a scene I have written about in a prior Holy Week post, “Behold the Man as Pilate washes His Hands.”

On the pretext that Jesus was from Galilee, thus technically a subject of Herod Antipas, Pilate sent Jesus to Herod in an effort to free himself from having to handle the trial. When Jesus did not answer Herod’s questions (Luke 23: 7-15) Herod sent him back to Pilate. Herod and Pilate had previously been indifferent, at best, and sometimes even antagonistic to each other, but over the trial of Jesus, they became friends. It was one of history’s most dangerous liaisons.

The trial before Pilate in the Gospel of John is described in seven distinct scenes, but the most unexpected twist occurs in the seventh. Unable to get around Pilate’s indecision about the guilt of Jesus in the crime of blasphemy, Jewish leaders of the Sanhedrin resorted to another tactic. Their charge against Jesus evolved into a charge against Pilate himself: “If you release him, you are no friend of Caesar” (John 19:12).

This stopped Pilate in his tracks. “Friend of Caesar” was a political honorific title bestowed by the Roman Empire. Equivalent examples today would be the Presidential Medal of Freedom bestowed upon a philanthropist, or a bishop bestowing the Saint Thomas More Medal upon a judge. Coins of the realm depicting Herod the Great bore the Greek insignia “Philokaisar” meaning “Friend of Caesar.” The title was politically a very big deal.

In order to bring about the execution of Jesus, the religious authorities had to shift away from presenting Jesus as guilty of blasphemy to a political charge that he is a self-described king and therefore a threat to the authority of Caesar. The charge implied that Pilate, if he lets Jesus go free, will also suffer a political fallout.

So then the unthinkable happens. Pilate gives clemency a final effort, and the shift of the Sadducees from blasphemy to blackmail becomes the final word, and in pronouncing it, the Chief Priests commit a far greater blasphemy than the one they accuse Jesus of:

“Shall I crucify your king? The Chief Priests answered, ‘We have no king but Caesar.”

Then Pilate handed him over to be crucified.