“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Behold, the Lamb of God

As Christmastide gives way to Ordinary Time in the Sunday Mass Gospel, John the Baptist connects the Lamb of God to the time of Abraham 2000 years before Christ.

As Christmastide gives way to Ordinary Time in the Sunday Mass Gospel, John the Baptist connects the Lamb of God to the time of Abraham 2000 years before Christ.

January 14, 2026, Ordinary Time

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: In 17 years writing for this blog I have produced about 850 posts from inside a prison cell with access only to an old typewriter. After I type them, I mail them to be scanned by an editor and then published at Beyond These Stone Walls. Once I mail a post, I have no means to ever see it again except on the rare occasion when I can make a photocopy. Once published, readers can see it but I cannot. So these 850 posts, at least for me, exist only in my mind. It seems inevitable that I would eventually write content that is familiar to readers.

After the Gospel passage about the Baptism of Jesus, the Church’s liturgy enters Ordinary Time. The Sunday Gospel this week, According to Saint John (1:29-34), begins with a declaration of John the Baptist as he saw Jesus coming toward him at the River Jordan: “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world.” This is the source of the Agnus Dei, the declaration we recite three times before the reception of the Eucharist at every Mass. The declaration has its origin in this Gospel passage.

It has another origin story as well, deep in the chasms of Salvation History. I set out to write about that this week, and then realized that I already had. So this post should sound familiar. I thank you for reading and sharing it.

+ + +

“This is the night when Christ broke the prison-bars of death and rose victorious from the underworld. Our birth would have been no gain had we not been redeemed.”

— from the Easter Vigil Exultet

You might readily see the irony of my invoking the subject of this post in the haunting passage above. It is from the Exultet, that wondrous proclamation of Salvation History as the Paschal Candle is blessed at the doors of the church in the liturgy for the Easter Vigil. The imagery of Christ breaking the prison bars of death may understandably have deep meaning for me. The excerpt recalls a scene from Holy Week that I once wrote about in “To the Spirits in Prison: When Jesus Descended into Hell.”

That post conveys the story referenced in the Second Letter of Saint Peter, about what happened to Jesus on what we now call Holy Saturday, that period of darkness between the Cross and the Resurrection.

Back in February 2025, I wrote a post entitled “On the Great Biblical Adventure, the Truth Will Make You Free.” It mentioned my recent acquisition of the much anticipated Ignatius Catholic Study Bible: Old and New Testament edited by Dr. Scott Hahn. That post also referred to a recent and surprising resurgence of biblical interest throughout the free world. I learned of that explosion of interest when Ignatius Press placed me on a waiting list for that particular bible, and I had to wait for its fourth or fifth printing. I have been lugging the weighty hardcover tome, consisting of 2,314 pages, around with me for months at this writing. I don’t seem to be able to part with it for long. It is a treasure trove of biblical insight and truth, filled not only with readable and scholarly translations of Sacred Scripture, but also with scholars’ notes on the biblical texts. From a historical perspective it draws clear connections between the Old and New Testaments. From a spiritual perspective it is as though a lamp has been relit opening for me, and hopefully also for you, a world of deeper meaning embedded within the texts. As I mentioned in a previous post, my goal has been two-fold: to educate, or rather reeducate myself on the story of God and us, and to avoid dropping the very heavy book on my foot in the process.

The interpretation of a religious text is a study called exegesis. It seeks to convey and understand both the literal and spiritual sense of biblical truths. Neither should be sacrificed in pursuit of the other. I have often described it this way: There is a story on its surface, which is true, and a far greater story in its depths which points to even greater truths. One way in which the spiritual truth of Scripture is expressed is in allegory. Jesus told many allegorical accounts in parables. Most readers are clear that the truth in these precious accounts is in the lesson they convey. Two of the most famous examples are the “Parable of the Good Samaritan” and the “Parable of the Prodigal Son,” both found in the Gospel of Luke. You know these stories well, and they need no explanation.

Most of Sacred Scripture is not conveyed in parable form, but as a historical narrative. Allegory is still very much a part of that narrative, and we are cheating our understanding of a text when we suppress its allegorical content. We should start by accepting both truths: the truth of the historical content of Scripture and the equal and sometimes even greater truth in its allegorical content. In this sense allegory refers to a story, poem, or picture that can be interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning, typically a moral or religious one. In the 19th and 20th centuries, fundamentalist Scripture scholars stripped allegory from their interpretations of the text, but at great cost. More modern scholars have restored it. One of them has been Dr. Scott Hahn.

When I cited an excerpt from the Exultet Proclamation from the Easter Vigil liturgy as I opened this post, I later realized that the Second Reading for the Easter Vigil Mass is one that I have pondered for a very long time. It is from Genesis 22:1-19, the story of God calling upon Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, his beloved son. “So momentous is this event in its outcome,” wrote Scott Hahn, “that it stands as one of the defining moments of Salvation History.” I have set out to study the great depths of this account and they are astonishing.

Abraham and Isaac

Isaac is a Hebrew name, of course, and it means “He laughs.” It has its origin in Genesis 17:16-17: “ ‘I will bless (Sarah) and moreover I will give you a son by her; I will bless her and she shall be the mother of nations; kings of peoples shall come from her.’ Then Abraham fell on his face and laughed, and said to himself, ‘Shall a child be born to a man who is a hundred years old? Shall Sarah, who is ninety years old, bear a child?’ ”

Abraham apparently gave little thought to the wisdom of falling to the ground and laughing at God. The fact that he “said it to himself” is no guarantee that God would not have heard it loud and clear. And so it was that the Word of God came to give the son of Abraham and Sarah the name “Isaac,” which means “He laughs.”

Abraham was apparently not the only one laughing. God seemed to get a chuckle out of it as well.

As the story progressed, the significance of Isaac’s birth was immediate. He was to be the fulfillment of God’s promise to Abraham. Isaac was to be the bearer of the covenant into future generations: “I will establish my covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for him and his descendants after him” (Genesis 17:19). Then the drama of the Book of Genesis reaches its greatest intensity with the heart-wrenching story of God’s call to Abraham to sacrifice as a burnt offering his beloved son upon the heights of Mount Moriah. Had Abraham shown anything less than heroic faith and obedience the grand narrative of the Bible would have developed very differently thereafter. Here is the Genesis account which became the Second Reading of our Easter Vigil liturgy.

From the Book of Genesis 22:1-18:

After these things, God tested Abraham and said to him, “Take your son, your only begotten son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering upon one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” So Abraham rose early in the morning, saddled his donkey, and he cut the wood for the burnt offering, and went to the place of which God had told him. … Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and laid it on the shoulders of his son to carry, and he took in his own hands the fire and the knife. So they went both of them together. Isaac said to his father, “Behold the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?” Abraham said, “God will provide himself the lamb for a burnt offering, my son.”

When they came to the place of which God had told him, Abraham built an altar there and laid the wood in order, and he bound Isaac his son and laid him on the altar upon the wood. Then Abraham put forth his hand and took the knife to slay his son. But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said, ‘Abraham, Abraham! Do not lay your hand on your son or do anything to him for now I know that you have not withheld your only begotten son from me.” Abraham then lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, behind him was a ram caught by his horns in a thicket. So Abraham went and took the lamb and offered it up as a burnt offering instead of his son. So Abraham called the name of that place YHWH YIR’EH, in Hebrew, “The Lord will see.”

It is from this very account that, twenty one centuries later, the Gospel of John (1:29) proclaims “Behold the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world.”

I have always felt that this account in Genesis was a presage, a looking far ahead, to the sacrifice of Jesus upon Golgotha. It is allegorical in that sense. The account is true on its literal face but it is also true that it echoes the Greatest Story Ever Told which will come many centuries later. All the elements are there. The Second Book of Chronicles (3:1) identifies Moriah as the site upon which, nearly one thousand years later, Solomon would build the Jerusalem Temple, and Calvary, where the only begotten Son of God was crucified, is a hillock in the Moriah range. So for the Hebrew reader of the story of the Crucifixion, there is a powerful sense of déjà vu: the place, the mount, Abraham placing the wood for sacrifice upon the back of Isaac, and is not the ram caught by its horns in the thicket highly reminiscent of the Crown of Thorns? But we cannot reminisce backwards. This amazing account from Genesis is a mysterious example of the power of biblical inspiration. Only in the mind of God, in the time of Genesis, was the story of Christ evident.

From Sheol to the Kingdom of Heaven

In the Old Testament, “to die” meant to descend to Sheol. It was our final destination. To rise from the dead, therefore, meant to rise from Sheol, but no one ever did. The concept of Sheol being the “underworld” is a simple employment of the cosmology of ancient Judaism which understood the abode of God and the heavens as being above the Earth, and Sheol, the place of the dead, as below it. This is the source of our common understanding of Heaven and hell, but it omits a vast theological comprehension of the death, Resurrection and Ascension of Jesus and the human need to understand our own death in terms of faith.

If, up to the time of Jesus, “to die” meant to descend into Sheol, then Jesus introduced an entirely new understanding of death in his statement from the Cross to the penitent criminal, Dismas, who pleaded from his own cross, “Jesus remember me when you come into your kingdom.” Jesus responded, “Today you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43). This is an account that I once told entitled, “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.”

It is by far the most widely read of our Holy Week posts, and not just at Holy Week. On the Cross, where the penitent criminal comes to faith while being crucified along with Jesus, God dissolves the bonds of death because death can have no power over Jesus. It is highly relevant for us that the conditions in which the penitent Dismas entered Paradise were to bear his cross and to come to faith.

It was at the moment Jesus declared, in His final word from the Cross, “It is finished,” that Heaven, the abode of God, opened for human souls for the first time in human history. The Gospels do not treat this moment lightly:

“It was now about the sixth hour [3:00 PM], and there was darkness over the whole land until the ninth hour while the sun’s light failed; and the curtain of the Temple was torn in two. Then Jesus, crying with a loud voice, said, ‘Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.’ Saying this he breathed his last.”

— Luke 23:44-46

“And behold, the curtain of the Temple was torn in two from top to bottom, and the Earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised ... When the centurion, and those who were with him keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake, and what took place, they were filled with awe, and said, ‘Clearly, this was the Son of God.’”

— Matthew 27:51-54

The veil of the Temple being torn in two appears also in Mark’s Gospel (15:38) and is highly significant. Two veils hung in the Jerusalem Temple. One was visible, separating the outer courts from the sanctuary. The other was visible only to the priests as it hung inside the sanctuary before its most sacred chamber in which the Holy of Holies dwelled (see Exodus 26:31-34). At the death of Jesus, the curtain of the Temple being torn from top to bottom is symbolic of salvation itself. Upon the death of Jesus, the barrier between the Face of God and His people was removed.

According to the works of the ancient Jewish historian, Josephus, the curtain barrier before the inner sanctuary that was torn in two was heavily embroidered with images of the Creation and the Cosmos. Its destruction symbolized the opening of Heaven, God’s dwelling place and the Angelic Realm, to human souls.

In ancient Israel in the time of Abraham and Isaac the concept of Sheol after death was closely connected with the grave and pictured only as a gloomy underworld hidden deep in the bowels of the Earth. There human souls descended after death (Genesis 37:35) to a joyless existence where the Lord is neither seen nor worshipped. Both the righteous and the wicked sank into the nether world (Genesis 44:31). Despite the apparent finality of death, Scripture displays great confidence in the power of God to deliver his people from its clutches. That confidence was made manifest in the deliverance of Jesus from his tomb after he displayed the power of God to the one place where he had always been absent, the realm of the dead. “For Christ also died for sins once and for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit, in which he went and declared to the spirits in prison who did not formerly obey when God’s patience waited in the days of Noah.” (1 Peter 3:18-20)

The essential point for us could not be clearer or more hopeful. Besides Jesus himself, the first to be sanctioned with a promise of paradise was a condemned prisoner who, even in the intense suffering of his own cross, refused to mock Jesus but rather came to believe and then place all his final hope in that belief. As I ended “Dismas, Crucified to the Right” Dismas was given a new view from his cross, a view beyond death away from the East of Eden, across the Undiscovered Country of Death, toward his sunrise and eternal home.

I have written many times that we live in a most important time. The story of Abraham told above took place twenty one centuries before the Birth of the Messiah. We now live in the twenty first century after. Christ is now at the very center of Salvation History.

+ + +

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please visit our new page: Abraham to Easter: The Bible Speaks, our collection of Scriptural exegesis for Beyond These Stone Walls.

+ + +

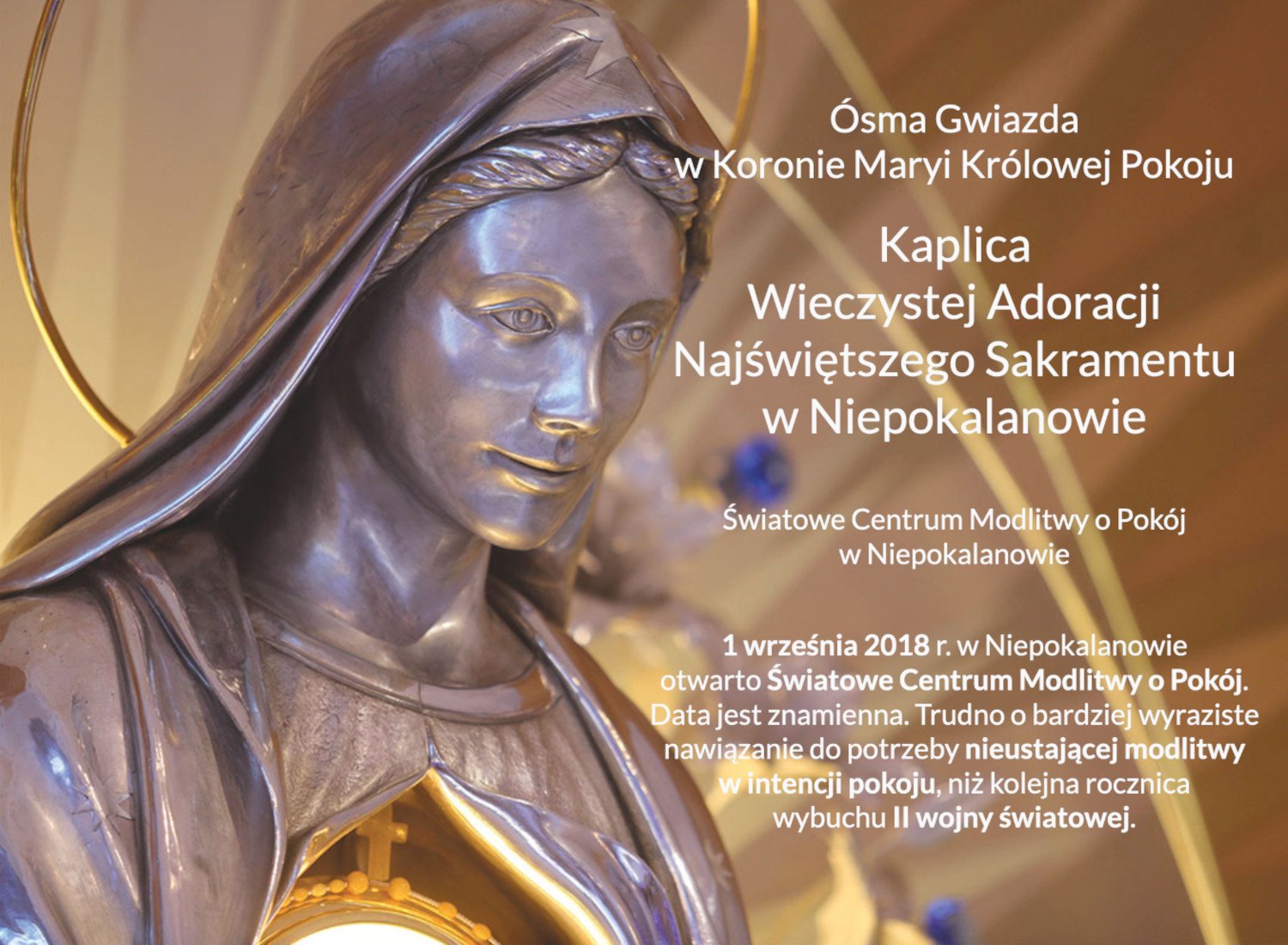

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Saint Gabriel the Archangel: When the Dawn from On High Broke Upon Us

The Gospel of Saint Luke opens with a news flash from the Archangel Gabriel for Zechariah the priest, and Mary — Theotokos — the new Ark of the Covenant.

Prisoners, including me, have no access at all to the online world. Though Wednesday is post day on Beyond These Stone Walls, I usually don’t get to see my finished posts until the following Saturday when printed copies arrive in the mail. So I was surprised one Saturday night when some prisoners where I live asked if they could read my posts. Then a few from other units asked for them in the prison library where I work.

Some titles became popular just by word of mouth. The third most often requested BTSW post in the library is “A Day Without Yesterday,” my post about Father Georges Lemaitre and Albert Einstein. The second most requested is “Does Stephen Hawking Sacrifice God on the Altar of Science?” Prisoners love the science/religion debate. But by far the most popular BTSW post is “Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed.” And as a result of it, dozens of prisoners have asked me for copies of the prayer to Saint Michael. I’m told it’s being put up on cell walls all over the prison.

Remember “Jack Bauer Lost The Unit On Caprica,” my post about my favorite TV shows? In the otherwise vast wasteland of American television, we’re overdue for some angelic drama. For five years in the 1980s, Michael Landon and Victor French mediated the sordid details of the human condition in Highway to Heaven. The series was created and produced by Michael Landon who thought TV audiences deserved a reminder of the value of faith, hope, and mercy as we face the gritty task of living. Highway to Heaven ended in 1989, but lived on in re-runs for another decade. Then in the 1990s, Della Reese and Roma Downey portrayed “Tess and Monica,” angelic mediators in Touched by an Angel which also produced a decade of re-runs.

Spiritual Battle on a Cosmic Scale

The angels of TV-land usually worked out solutions to the drama of being human within each episode’s allotted sixty minutes. That’s not so with the angels of Scripture. Most came not with a quick fix to human madness, but with a message for coping, for giving hope, for assuring a believer, or, in the case of the Angel of the Annunciation, for announcing some really big news on a cosmic scale — like salvation! What the angels of Scripture do and say has deep theological symbolism and significance, and in trying times interest in angels seems to thrive. The Archangel Gabriel dominates the Nativity Story of Saint Luke’s Gospel, but who is he and what is the meaning of his message?

We first meet Gabriel five centuries before the Birth of Christ in the Book of Daniel. The Hebrew name, “Gabri’El” has two meanings: “God is my strength,” and “God is my warrior.” As revealed in “Angelic Justice,” the Hebrew name Micha-El means “Who is like God?” The symbolic meaning of these names is portrayed vividly as Gabriel relates to Daniel the cosmic struggle in which he and Michael are engaged:

“Fear not, Daniel, for from the first day that you set your mind to understand, and humbled yourself before God, your words have been heard, and I have come because of your words. The prince of the kingdom of Persia withstood me twenty-one days, but Michael, one of the chief princes, came to help me. So I left him there with the prince of the kingdom of Persia, and came to make you understand what is to befall your people in the latter days . . . But I will tell you what is inscribed in the Book of Truth: there is none who contends at my side against these except Michael.”

— Daniel 10:12-14, 21

In the Talmud, the body of rabbinic teaching, Gabriel is understood to be one of the three angels who appeared to Abraham to begin salvation history, and later led Abraham out of the fire into which Nimrod cast him. The Talmud also attributes to Gabriel the rescue of Lot from Sodom. In Christian apocalyptic tradition, Gabriel is the “Prince of Fire” who will prevail in battle over Leviathan at the end of days. Centuries after the Canon of Old and New Testament Scripture was defined, Gabriel appears also in the Qu’ran as a noble messenger.

In Jewish folklore, Gabriel was in the role of best man at the marriage of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. I found that a strange idea at first, but then it dawned on me: Who else were they going to ask? In later rabbinic Judaism, Gabriel watches over man at night during sleep, so he is invoked in the bedside “Shema” which observant Jews must recite at bedtime in a benediction called the Keri’at Shema al ha_Mitah:

“In the name of the God of Israel, may Michael be on my right hand, Gabriel on my left hand, Uriel before me, behind me Raphael, and above my head, the Divine Presence. Blessed is he who places webs of sleep upon my eyes and brings slumber to my eyelids. May it be your will to lay me down and awaken me in peace. Blessed are You, God, who illuminates the entire world with his glory.”

In a well written article in the Advent 2010 issue of Word Among Us (www.WAU.org) – “Gabriel, the Original Advent Angel,” Louise Perrotta described Gabriel’s central message to Daniel:

“History is not a haphazard series of events. Whatever the dark headlines — terrorist attacks, natural disasters, economic upheavals — we’re in the hands of a loving and all-powerful God. Earthly regimes will rise and fall, and good people will suffer. But . . . at an hour no one knows, God will bring evil to an end and establish His eternal kingdom.”

East of Eden

The Book of Tobit identifies the Archangel Raphael as one of seven angels who stand in the Presence of God. Scripture and the Hebrew Apocryphal books identify four by name: Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, and Uriel. The other three are not named for us. In rabbinic tradition, these four named angels stand by the Celestial Throne of God at the four compass points, and Gabriel stands to God’s left. From our perspective, this places Gabriel to the East of God, a position of great theological significance for the fall and redemption of man.

In a previous post, “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden,” I described the symbolism of “East of Eden,” a title made famous by the great American writer, John Steinbeck, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for it in 1962. I don’t mean to brag (well, maybe a little!) but a now-retired English professor at a very prestigious U.S. prep school left a comment on “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden” comparing it to Steinbeck’s work. This has absolutely nothing to do with the Archangel Gabriel, but I’ve been waiting for a subtle chance to mention it again! (ahem!) But seriously, in the Genesis account of the fall of man, Adam and Eve were cast out of Eden to the East (Genesis 3:24). It was both a punishment and a deterrent when they disobeyed God by eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil:

“Behold, the man has become like one of us, knowing good from evil; and now, lest he put out his hand and take also from the Tree of Life, and eat, and live forever,’ therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the Garden of Eden to till the ground from which he was taken. He drove the man out, and to the east of the Garden of Eden he placed a Cherubim, and a flaming sword which turned every which way, to guard the way to the Tree of Life.”

— Gen.3: 22-24

A generation later, after the murder of his brother Abel, Cain too “went away from the presence of the Lord and dwelt in the land of Nod, East of Eden.” (Genesis 4:16). The land of Nod seems to take its name from the Hebrew “nad” which means “to wander,” and Cain described his fate in just that way: “from thy face I shall be hidden; I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth” (Genesis 4:14). The entire subsequent history of Israel is the history of that wandering East of Eden. I wonder if it is also just coincidence that the Gospel of Saint Matthew, the only source of the story of the Magi, has the Magi seeing the Star of Bethlehem “in the east” and following it out of the east.

An Immaculate Reception

In rabbinic lore, Gabriel stands in the Presence of God to the left of God’s throne, a position of great significance for his role in the Annunciation to Mary. Gabriel thus stands in God’s Presence to the East, and from that perspective in St. Luke’s Nativity Story, Gabriel brings tidings of comfort and joy to a waiting world in spiritual exile East of Eden.

The Archangel’s first appearance is to Zechariah, the husband of Mary’s cousin, Elizabeth. Zechariah is told that he and his wife are about to become the parents of John the Baptist. The announcement does not sink in easily because, like Abraham and Sarah at the beginning of salvation history, they are rather on in years. Zechariah is about to burn incense in the temple, as close to the Holy of Holies a human being can get, when the archangel Gabriel appears with news:

“Fear fell upon him. But the angel said to him, ‘Do not be afraid, Zechariah, for your prayer is heard, and your wife, Elizabeth will bear you a son, and you shall call his name John . . . and he will be filled with the Holy Spirit even from his mother’s womb, and he will turn many of the sons of Israel to the Lord their God and will go before him in the spirit and power of Elijah . . .’”

— Luke 1:12-15

This news isn’t easily accepted by Zechariah, a man of deep spiritual awareness revered for his access to the Holy of Holies and his connection to God. Zechariah doubts the message, and questions the messenger. It would be a mistake to read the Archangel Gabriel’s response in a casual tone. Hear it with thunder in the background and the Temple’s stone floor trembling slightly under Zechariah’s feet:

“I am Gabriel who stand in the Presence of God . . . and behold, you will be silent and unable to speak until the day that these things come to pass.”

I’ve always felt great sympathy for Zechariah. I imagined him having to make an urgent visit to the Temple men’s room after this, followed by the shock of being unable to intone the Temple prayers.

Zechariah was accustomed to great deference from people of faith, and now he is scared speechless. I, too, would have asked for proof. For a cynic, and especially a sometimes arrogant one, good news is not easily taken at face value.

Then six months later “Gabriel was sent from God to a city of Galilee named Nazareth, to a virgin betrothed to a man whose name was Joseph, of the House of David, and the virgin’s name was Mary.” (Luke 1: 26-27). This encounter was far different from the previous one, and it opens with what has become one of the most common prayers of popular devotion.

Gabriel said, “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee.” His words became the Scriptural basis for the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, that and centuries of “sensus fidelium,” the consensus of the faithful who revere her as “Theotokos,” the God-Bearer. Mary, like Zechariah, also questions Gabriel about the astonishing news. “How can this be since I have not known man?” There is none of the thunderous rebuke given to Zechariah, however. Saint Luke intends to place Gabriel in the presence of his greater, a position from which even the Archangel demonstrates great reverence and deference.

It has been a point of contention with non-Catholics and dissenters for centuries, but the matter seems so clear. There’s a difference between worship and reverence, and what the Church bears for Mary is the deepest form of reverence. It’s a reverence that came naturally even to the Archangel Gabriel who sees himself as being in her presence rather than the other way around. God and God alone is worshiped, but the reverence bestowed upon Mary was found in only one other place on Earth. That place was the Ark of the Covenant, in Hebrew, the “Aron Al-Berith,” the Holy of Holies which housed the Tablets of the Old Covenant. It was described in 1 Kings 8: 1-11, but the story of Gabriel’s Annunciation to Mary draws on elements from the Second Book of Samuel.

These elements are drawn by Saint Luke as he describes Mary’s haste to visit her cousin Elizabeth in the hill country of Judea. In 2 Samuel 6:2, David visits this very same place to retrieve the Ark of the Covenant. Upon Mary’s entry into Elizabeth’s room in Saint Luke’s account, the unborn John the Baptist leaps in Elizabeth’s womb. This is reminiscent of David dancing before the Ark of the Covenant in 2 Samuel 6:16.

For readers “with eyes to see and ears to hear,” Saint Luke presents an account of God entering into human history in terms quite familiar to the old friends of God. God himself expressed in the Genesis account of the fall of man that man has attempted to “become like one of us” through disobedience. Now the reverse has occurred. God has become one of us to lead us out of the East, and off the path to eternal darkness and death.

In Advent, and especially today the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, we honor with the deepest reverence Mary, Theotokos, the Bearer of God and the new Ark of the Covenant. Mary, whose response to the Archangel Gabriel was simple assent:

“Let it be done to me according to your word.”

“Then the Dawn from On High broke upon us, to shine on those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death, and to guide our feet on the way to peace.”

— Luke 1:78-79

+ + +

Note from Fr Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post in honor of the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception. You may also like these related posts:

The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God

Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed

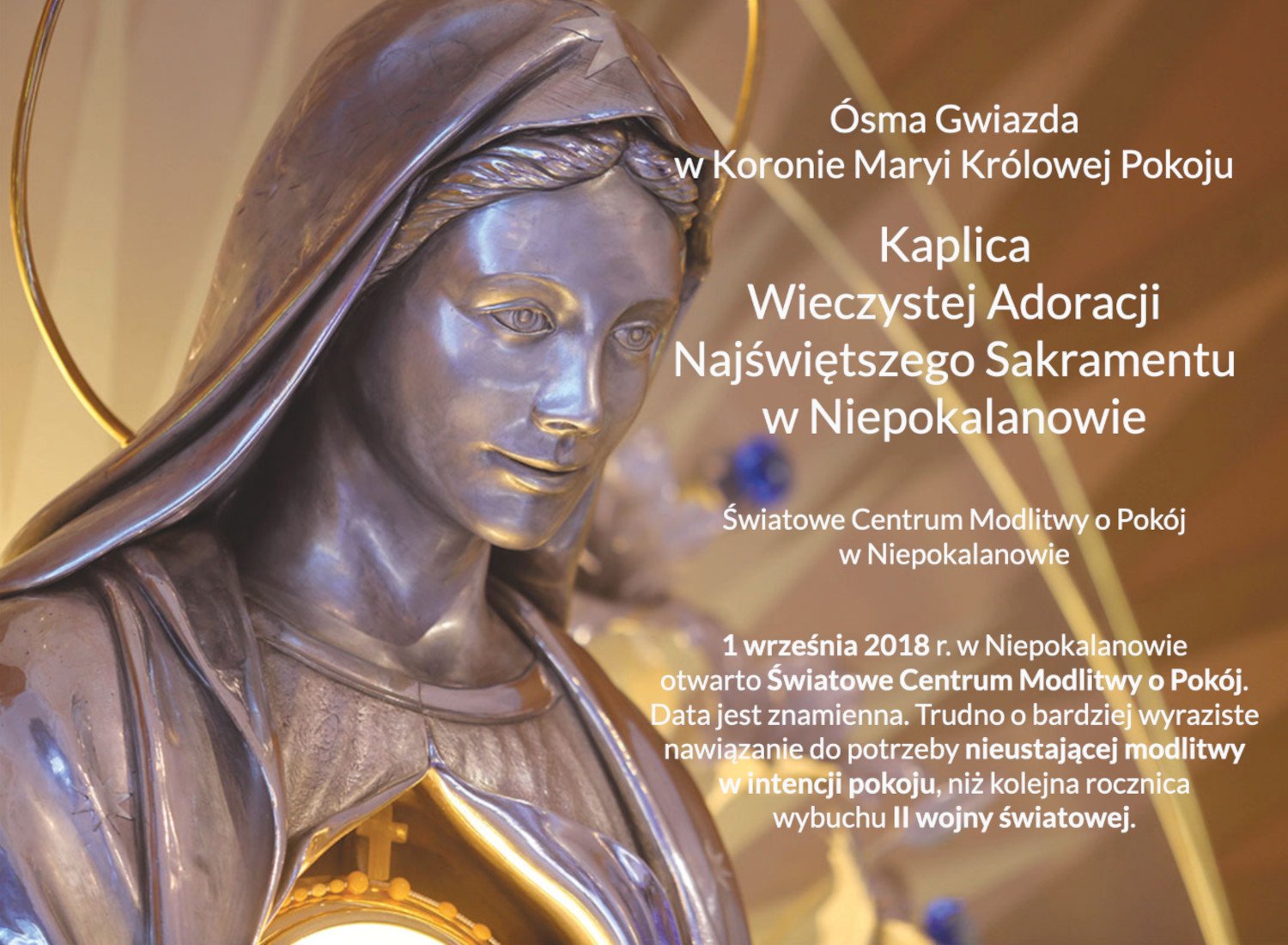

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”