“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Hand of God and the Story of a Soul

In two inspiring posts, Fr Gordon MacRae wrote of Michelangelo and an ancient sculpture unearthed out of legend and the legend come true from St Therese of Lisieux.

In two inspiring posts, Fr Gordon MacRae wrote of Michelangelo and an ancient sculpture unearthed out of legend and a legend come true from St Therese of Lisieux.

Note to readers from Father Gordon MacRae: I recently wrote that a prison construction project has caused me and others where I live to be temporarily relocated for a few weeks to a crowded dormitory from where I am unable to write. Once the project is completed later this month, I will be moved back and will hopefully resume writing new posts.

I am currently living in a room with 23 other prisoners crowded into a small and noisy space. At first sight it reminded me of a FEMA shelter, but at least there was no disaster that preceded it. I cannot complain. Our friend Pornchai Moontri spent five full months in ICE detention in a similar space packed with 70 detainees awaiting deportation. You should not miss that nightmare and his final liberation in “ICE Finally Cracks: Pornchai Moontri Arrives in Thailand.”

During my writing hiatus some relevant older posts are being restored at Beyond These Stone Walls and added to our various Library Categories. Our site developer thinks that some of these posts deserve a new audience or a second look. This week we are presenting two at a time when inspiration might be in short supply. I hope you will read and share them.

+ + +

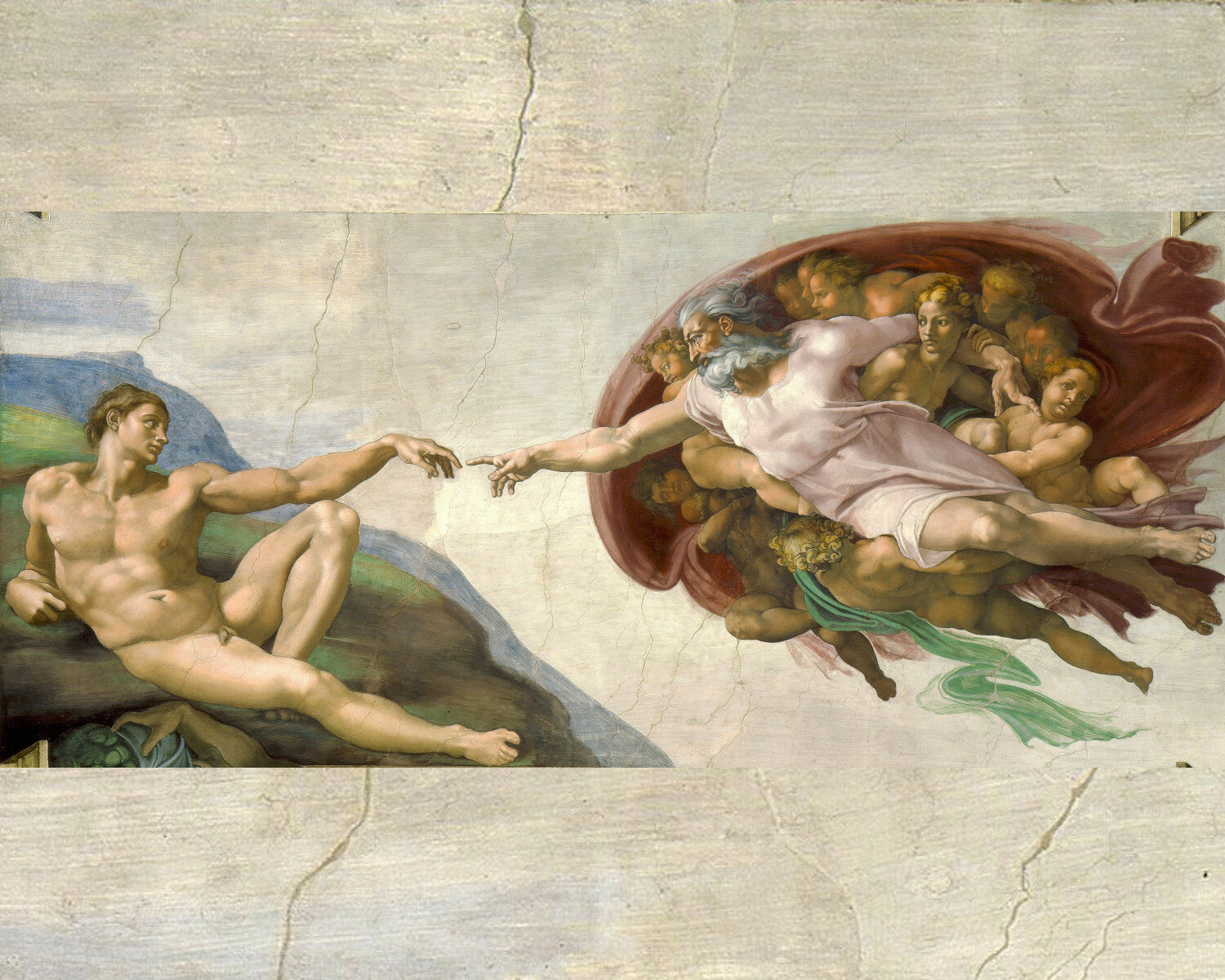

Michelangelo and the Hand of God

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born in 1475 in the small Italian village of Caprese. He grew up in Florence, the artistic center of the early Renaissance, a period of artistic innovation and accomplisnhment that began at the time Michelangelo was born. In many ways, the masterpieces surrounding him in Florence were themselves his best teachers. They included ancient Greek and Roman statuary and the paintings, sculpture, and architecture of the early Renaissance masters.

As a child, Michelangelo preferred drawing to schoolwork which often earned his father’s stern disapproval. For historical context, Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492 just as thirteen year old Michelangelo was apprenticed to a sculptor in Florence. From there, he took up residence in the home of Lorenzo dé Medici, the leading art patron of Florence.

The Medici household was a gathering place for artists, poets, and philosophers. During this time, Michelangelo studied under Bertoldo di Giovanni, an aging master who had trained with Donatello, the greatest sculptor of 15th-century Florence. This exposure proved providencial when, at the age of 30, Michelangelo was on hand in Rome to help unearth and identify the excavation of a sculptural legend, The Laocoön (pronounce Low-OCK-oh-one), a massive ancient sculpture dating from the Second Century BC that had been missing for over a thousand years.

The Laocoön also had a massive influence on all future sculptures and paintings by Michelangelo that became the enduring treasures of the Catholic Church. The Laocoön stands today in the Vatican Museum. This is that story, and it is fascinating. Don’t miss:

Michelangelo and the Hand of God: Scandal at the Vatican.

+ + +

A Shower of Roses

Saint Therese of Lisieux was a French Carmelite nun called “The Little Flower of Jesus.” She became one of the most beloved saints of the Catholic Church in modern times. Born at Alencon, France, with the name, Therese Martin, she was deeply pious from childhood and entered the Carmelite Convent at Lisieux at the young age of 15.

Therese exemplified what she called her “Little Way,” a devotion to God both childlike and profound. She sought holiness through the offering of small actions and humble tasks. Her goodness was so remarkable that her superiors asked her to write an account of her life and spiritual journey.

The result was “Story of a Soul” written in French in 1898 and translated into English in 1958. It is today the most widely read spiritual memoir of our time. Therese died at the young age of 24 and was canonized in 1925. She is today a Doctor of the Church.

The many miracles attributed to Saint Therese gave meaning to her cryptic promise, “After my death, I will let fall a shower of roses.” One of them, a small one, fell to me. Please read and share anew,

A Shower of Roses.

Michelangelo and the Hand of God: Scandal at the Vatican

Seen with the eyes of any faith at all, this story leaves you wondering just how the hand of God is writing your own history. The story is true, and it’s fascinating.

Seen with the eyes of any faith at all, this story leaves you wondering just how the hand of God is writing your own history. The story is true, and it’s fascinating.

“Calendar with frontal nudity – Not Allowed.” I received that notice from the prison mail room several years ago instructing me that I had two choices: have the pornographic contraband destroyed or sent out. I had no idea what it was, but the sender was my younger brother, Scott. I was furious with Scott. I thought his judgment had fallen off a cliff somewhere and he tried to send me a Playboy calendar — or worse. “He should know better!” I thought. “What on earth would make him think I would want a nude calendar?”

The next day I received a letter from Scott: “I hope you like the calendar!” he wrote. That confirmed it! My brother had gone mad! When I finally reached him by telephone, he told me that the calendar was entitled “Vatican City: Scenes from the Sistine Chapel.”

I never did get to see the calendar. I had it returned to my brother with an apology from me for thinking he had lost his marbles. I’m not sure at what point Michelangelo’s work became pornography. It’s a recent phenomenon, but not necessarily a new one. In Witness to Hope, his famed biography of Pope John Paul II, George Weigel described the Holy Father’s insistence that Michelangelo’s work be restored to its original design:

“In addition to authorizing the restoration of the frescoes . . . John Paul made sure, when it came time to clean the Last Judgment, that the restorers removed about half the leggings, breechcloths, and other drapings with which prudish churchmen had hidden Michelangelo’s nudes, years after the masterpiece had been completed.”

In the years before I was accused and sent to prison ( see the About Page), I had a beautiful framed reproduction of Michelangelo’s famed “Creation of Adam,” one of the magnificent frescoes he painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel between 1508 and 1512. It’s an image that just about every one of the world’s one billion Catholics has seen whether they have visited the Eternal City or not. A few years ago, a priest in Ottawa sent me a card bearing a part of that same image, the hand of God reaching toward the hand of Adam to bestow life. It was on my cell wall for two years before it disappeared one day when I was moved from place to place.

When things aren’t “Going My Way” — which you know is often if you’ve been reading my posts — I sometimes drift into thinking that God’s hand in history is an illusion. Then I come across stories like the one I’m about to tell you — the story of how Michelangelo came to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

HOLD ON! Don’t go just yet! I promise not to write a history lesson every week, but this is one of the strangest stories I have ever encountered, and I just have to write about it. So bear with me, please, as I again meander down that path. Seen with the eyes of any faith at all, this story leaves you wondering just how the hand of God is writing your own history. The story is true, and it’s fascinating.

The Poseidon Adventure

In Greek mythology, Laocoön was a priest of the Roman god of the sea, Neptune. He tried to dissuade the leaders of Troy from bringing the famed Trojan Horse into the city.

“What madness, citizens, is this? Have you not learned enough of Grecian fraud to be on your guard against it? For my part, I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts.”

In the mythological story, Poseidon, the Greek version of Neptune, became angry at the Trojans and sent sea serpents to kill Laocoön and his sons just as he tried to convince the Trojans not to bring the horse through the city gates. As the Trojans witnessed the death of Laocoön, they took it as a sign not to heed his advice. They brought the Trojan Horse inside the city walls to their peril. You know the rest.

In 38 B.C., on the Island of Rhodes off the coast of Turkey, three Greek sculptors created The Laocoön, a magnificent freestanding marble sculpture depicting the attack of Poseidon’s serpents upon the priest and his sons. It was the world’s most famous sculpture, and the best known example of ancient Hellenistic art known to exist at that time. Over centuries, The Laocoön became legendary. Then it became lost. With one city state sacking another, the magnificent Laocoön faded from history, and its very existence became a legend. Pliny wrote of having seen it, and described its every detail in the late first century, A.D. By the time of Michelangelo 1500 years later, every sculptor knew the legend of The Laocoön, but it had been many centuries since anyone had seen it.

When in Rome

In 1505, 30-year-old Michelangelo Buonarroti was commissioned to create life-size free standing marble sculptures of each of the Twelve Apostles for the Cathedral at Florence. It was an extremely ambitious plan that he doubted he could complete in his lifetime. Michelangelo began his work on a life size sculpture of St. Matthew, the first of the immense project.

Just after beginning, however, Michelangelo was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II. In a game of one-up-manship typical of the time, the Pope usurped the Florence project by ordering Michelangelo to stay in Rome and create a marble tomb that would immortalize the pope. It was originally intended to be the most ambitious monument the world had ever seen, comprising forty life-sized marble sculptures. Under duress, Michelangelo began sketching out this folly.

Scandal Time — The Prequel

What was going on in the Catholic Church parallel to all this is an eye-opener. Over a roughly sixty year period from 1470 to 1530, a succession of popes became embroiled in the labyrinthine temporal politics of the reigning princes and kings of the Italian city-states. It was all, to say the least, colorful and overtly scandalous. If you ever feared the Church may not endure the scandals of our day, think again! They are as nothing next to what went on in Rome five centuries ago.

Pope Julius II reigned for a decade from 1503 to 1513. History considers him one of the more brilliant and just of the Renaissance popes, yet he was suspected of having bribed his way into the papacy. His chief concern as pope was to expand the Papal States to compete more effectively — some would say more ruthlessly — among the city-state model of government in place at the time.

The principal fault of popes in the Renaissance period was their unbridled capitulation to the agendas and values of the secular world, and it led to schism — to the Protestant Reformation which turned out to be anything but a reform. Removing all central teaching authority from their churches caused dissension and divisions splitting them into hundreds of sects. Those divisions continue today.

It’s an ironic twist of history that many of those who hold the Catholic Church in contempt for caving in to secularism in the 16th Century also demand that the Church repeat the mistake in the 21st Century. In Connecticut last year, legislation was proposed to strip the Catholic Church of authority over Catholic parishes in that state. Its major proponents were largely members of Voice of the Faithful whose motto is “Keep the Faith; change the Church.” Those who do not understand history are doomed to repeat it.

Digging Up The Past

Back to Michelangelo. Just months into his conscripted labor on the Pope’s personal tomb, Michelangelo dismayed of ever completing it, and decided to flee from Rome to return to Florence against the Pope’s wishes. Pope Julius was long on ego and short on funds. He dedicated most of the funds available to the restoration of St. Peter’s Basilica and the architectural marvel that is the centerpiece of our Church today. The Pope’s unfunded ambition for his 40-sculpture personal tomb left Michelangelo in near despair.

This is where the story gets bizarre. Just as Michelangelo prepared to leave Rome in 1506, however, he visited the home of a friend who happened to be the son of Guiliano de Sangallo, the chief architect for Pope Julius’s renovation and enlargement of St. Peter’s Basilica. As Michelangelo visited his friend, a messenger came charging in.

On that same day in Rome in 1506, landowner Felice di Fredi was clearing his vineyards of large stones. He had no idea — or at least no appreciation — that the stones were the remnants of ancient walls that once surrounded the golden home of Emperor Nero.

“CLUNK!” Fredi’s shovel struck something large, white, and very hard. In four large sections, he dug up a large marble structure. Someone sent word to the papal architect, Guiliano de Sangallo, who set out on horseback accompanied by his son and their guest, Michelangelo to assess the unearthed marble treasure.

Upon arrival, the elder de Sangallo took one look at the sculpture and exclaimed: “It’s The Laocoön that Pliny describes!” Out of long buried history, the world’s oldest and most famous freestanding marble sculpture arrived at the Vatican to cheers and applause accompanied by Michelangelo himself, the world’s most accomplished sculptor of the time. The Laocoön remains in the Vatican Museum to this day.

Michelangelo was profoundly influenced by The Laocoön. It was the turning of a sharp corner in the history of art, and in the enduring treasures of our own faith history. The odds against Michelangelo being at that very place in time to witness the unearthing of the world’s most famed marble sculpture were astronomically impossible. Yet there he was, under duress, and as a direct result of the secular scandal of the Renaissance papacy.

After taking some time to study The Laocoön, Michelangelo left Rome for Florence to resume his work on the sculpture of St. Matthew. The Laocoön was a large part of his motivation. Michelangelo was in awe of its design and tortured realism of human bodies in motion, and was eager to apply that same realism to his first love, marble sculpture. He dug furiously at the marble block in Florence believing that he was to free St. Matthew imprisoned within it.

Two years later, Michelangelo was on his back on high scaffolding painting the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. It was a discipline imposed on him by Pope Julius for his disobedience. Michelangelo was angry and resentful, and his powerful emotions exploded into his art on the Sistine ceiling. The expressive and powerful recreation of humans in motion that Michelangelo first witnessed in The Laocoön was the principal model for his design and imagery in the Sistine Chapel ceiling — that, and his own deeply felt anger and disillusionment with the Pope and his ambition.

When Christ placed the Church in the hands of human beings, He knew exactly what was in store for history. The very art with which the world now associates our faith came as the result of the most scandalous adventures in human folly the Church has ever seen.

The Church Triumphant, the Church of faith, is parallel to the Church of human history with all its corruption and failings. It’s a lesson to be learned for those reeling from the burden of scandal in our Church in this day. It’s true that the gates of Hell cannot prevail against it.

But not for lack of trying!