“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

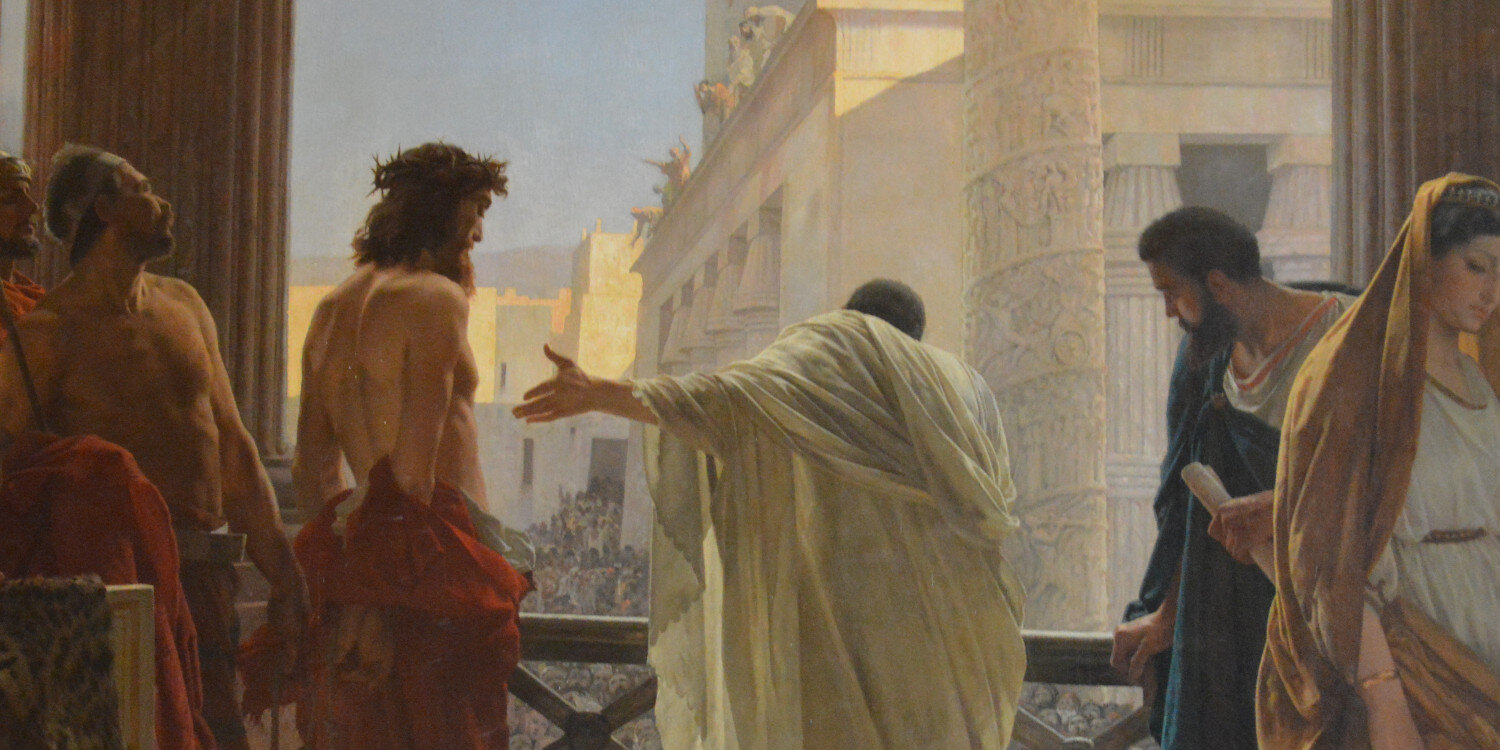

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

There are few things in life that a priest could hear with greater impact than what was revealed to me in a recent letter from a reader of These Stone Walls. After stumbling upon TSW several months ago, the writer began to read these pages with growing interest. Since then, she has joined many to begin the great adventure of the two most powerful spiritual movements of our time: Marian Consecration and Divine Mercy. In a recent letter she wrote, “I have been a lazy Catholic, just going through the motions, but your writing has awakened me to a greater understanding of the depths of our faith.”

I don’t think I actually have much to do with such awakenings. My writing doesn’t really awaken anyone. In fact, after typing last week’s post, I asked my friend, Pornchai Moontri to read it. He was snoring by the end of page two. I think it is more likely the subject matter that enlightens. The reader’s letter reminded me of the reading from Saint Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians read by Pornchai a few weeks ago, quoted in “De Profundis: Pornchai Moontri and the Raising of Lazarus”:

“Awake, O sleeper, and rise from the dead, and Christ will give you light.”

I may never understand exactly what These Stone Walls means to readers and how they respond. That post generated fewer comments than most, but within just hours of being posted, it was shared more than 1,000 times on Facebook and other social media.

Of 380 posts published thus far on These Stone Walls, only about ten have generated such a response in a single day. Five of them were written in just the last few months in a crucible described in “Hebrews 13:3 Writing Just This Side of the Gates of Hell.” I write in the dark. Only Christ brings light.

Saint Paul and I have only two things in common — we have both been shipwrecked, and we both wrote from prison. And it seems neither of us had any clue that what we wrote from prison would ever see the light of day, let alone the light of Christ. There is beneath every story another story that brings more light to what is on the surface. There is another story beneath my post, “De Profundis.” That title is Latin for “Out of the Depths,” the first words of Psalm 130. When I wrote it, I had no idea that Psalm 130 was the Responsorial Psalm for Mass before the Gospel account of the raising of Lazarus:

“Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord!

Lord hear my voice!

Let your ears be attentive

to my voice in supplication…

”I wait for the Lord, my soul waits,

and I hope in his word;

my soul waits for the Lord

more than sentinels wait for the dawn,

more than sentinels wait for the dawn.”

Notice that the psalmist repeats that last line. Anyone who has ever spent a night lying awake in the oppression of fear or dark depression knows the high anxiety that accompanies a long lonely wait for the first glimmer of dawn. I keep praying that Psalm — I have prayed it for years — and yet Jesus has not seen fit to fix my problems the way I want them fixed. Like Saint Paul, in the dawn’s early light I still find myself falsely accused, shipwrecked, and unjustly in prison.

Jesus also prayed the Psalms. In a mix of Hebrew and Aramaic, he cries out from the Cross, “Eli, Eli làma sabach-thàni?” It is not an accusation about the abandonment of God. It is Psalm 22, a prayer against misery and mockery, against those who view the cross we bear as evidence of God’s abandonment. It is a prayer against the use of our own suffering to mock God. It’s a Psalm of David, of whom Jesus is a descendant by adoption through Joseph:

“Eli, Eli làma sabach-thàni?

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are You so far from my plea,

from the words of my cry? …

… All who see me mock at me;

they curse me with parted lips,

they wag their heads …

Indeed many dogs surround me,

a pack of evildoers closes in upon me;

they have pierced my hands and my feet.

I can count all my bones …

They divide my garments among them;

for my clothes they cast lots.”

So maybe, like so many in this world who suffer unjustly, we have to wait in hope simply for Christ to be our light. And what comes with the light? Suffering does not always change, but its meaning does. Take it from someone who has suffered unjustly. What suffering longs for most is meaning. People of faith have to trust that there is meaning to suffering even when we cannot detect it, even as we sit and wait to hear, “Upon the Dung Heap of Job: God’s Answer to Suffering.”

The Passion of the Christ

Last year during Holy Week, two Catholic prisoners had been arguing about why the date of Easter changes from year to year. They both came up with bizarre theories, so one of them came to ask me. I explained that in the Roman Church, Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox (equinox is from the Latin, “equi noctis,” for “equal night”). The prisoner was astonished by my ignorance and said, “What BS! Easter is forty days after Ash Wednesday!”

Getting to the story beneath the one on the surface is important to understand something as profound as the events of the Passion of the Christ. You may remember from my post, “De Profundis,” that Jesus said something perplexing when he learned of the illness of Lazarus:

“This illness is not unto death; it is for the glory of God, so that the Son of God may be glorified by means of it”

The irony of this is clearer when you see that it was the raising of Lazarus that condemned Jesus to death. The High Priests were deeply offended, and the insult was an irony of Biblical proportions (no pun intended). Immediately following upon the raising of Lazarus, “the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered the council” (the Sanhedrin). They were in a panic over the signs performed by Jesus. “If he goes on like this,” they complained, “the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place (the Jerusalem Temple) and our nation” (John 11 47-48).

The two major religious schools of thought in Judaism in the time of Jesus were the Pharisees and the Sadducees. Both arose in Judaism in the Second Century B.C. and faded from history in the First Century A.D. At the time of Jesus, there were about 6,000 Pharisees. The name, “Pharisees” — Hebrew for “Separated Ones” — came as a result of their strict observance of ritual piety, and their determination to keep Judaism from being contaminated by foreign religious practices. Their hostile reaction to the raising of Lazarus had nothing to do with the raising of Lazarus, but rather with the fact that it occurred on the Sabbath which was considered a crime.

Jesus actually had some common ground with the Pharisees. They believed in angels and demons. They believed in the human soul and upheld the doctrine of resurrection from the dead and future life. Theologically, they were hostile to the Sadducees, an aristocratic priestly class that denied resurrection, the soul, angels, and any authority beyond the Torah.

Both groups appear to have their origin in a leadership vacuum that occurred in Jerusalem between the time of the Maccabees and their revolt against the Greek king Antiochus Epiphanies who desecrated the Temple in 167 B.C. It’s a story that began Lent on These Stone Walls in “Semper Fi! Forty Days of Lent Giving Up Giving Up.”

The Pharisees and Sadducees had no common ground at all except a fear that the Roman Empire would swallow up their faith and their nation. And so they came together in the Sanhedrin, the religious high court that formed in the same time period the Pharisees and Sadducees themselves had formed, in the vacuum left by the revolt that expelled Greek invaders and their desecration of the Temple in 165 B.C.

The Sanhedrin was originally composed of Sadducees, the priestly class, but as common enemies grew, the body came to include Scribes (lawyers) and Pharisees. The Pharisees and Sadducees also found common ground in their disdain for the signs and wonders of Jesus and the growth in numbers of those who came to believe in him and see him as Messiah.

The high profile raising of Lazarus became a crisis for both, but not for the same reasons. The Pharisees feared drawing the attention of Rome, but the Sadducees felt personally threatened. They denied any resurrection from the dead, and could not maintain religious influence if Jesus was going around doing just that. So Caiaphas, the High Priest, took charge at the post-Lazarus meeting of the Sanhedrin, and he challenged the Pharisees whose sole concern was for any imperial interference from the Roman Empire. Caiaphas said,

“You know nothing at all. You do not understand that it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people, so that the whole nation should not perish”

The Gospel of John went on to explain that Caiaphas, being High Priest, “did not say this of his own accord, but to prophesy” that Jesus was to die for the nation, “and not for the nation only, but, to gather into one the children of God” (John 11: 41-52). From that moment on, with Caiaphas being the first to raise it, the Sanhedrin sought a means to put Jesus to death.

Caiaphas presided over the Sanhedrin at the time of the arrest of Jesus. In the Sanhedrin’s legal system, as in our’s today, the benefit of doubt was supposed to rest with the accused, but … well … you know how that goes. The decision was made to find a reason to put Jesus to death before any legal means were devised to actually bring that about.

Behold the Man!

The case found its way before Pontius Pilate, the Roman Prefect of Judea from 25 to 36 A.D. Pilate had a reputation for both cruelty and indecision in legal cases before him. He had previously antagonized Jewish leaders by setting up Roman standards bearing the image of Caesar in Jerusalem, a clear violation of the Mosaic law barring graven images.

All four Evangelists emphasize that, despite his indecision about the case of Jesus, Pilate considered Jesus to be innocent. This is a scene I have written about in a prior Holy Week post, “Behold the Man as Pilate washes His Hands.”

On the pretext that Jesus was from Galilee, thus technically a subject of Herod Antipas, Pilate sent Jesus to Herod in an effort to free himself from having to handle the trial. When Jesus did not answer Herod’s questions (Luke 23: 7-15) Herod sent him back to Pilate. Herod and Pilate had previously been indifferent, at best, and sometimes even antagonistic to each other, but over the trial of Jesus, they became friends. It was one of history’s most dangerous liaisons.

The trial before Pilate in the Gospel of John is described in seven distinct scenes, but the most unexpected twist occurs in the seventh. Unable to get around Pilate’s indecision about the guilt of Jesus in the crime of blasphemy, Jewish leaders of the Sanhedrin resorted to another tactic. Their charge against Jesus evolved into a charge against Pilate himself: “If you release him, you are no friend of Caesar” (John 19:12).

This stopped Pilate in his tracks. “Friend of Caesar” was a political honorific title bestowed by the Roman Empire. Equivalent examples today would be the Presidential Medal of Freedom bestowed upon a philanthropist, or a bishop bestowing the Saint Thomas More Medal upon a judge. Coins of the realm depicting Herod the Great bore the Greek insignia “Philokaisar” meaning “Friend of Caesar.” The title was politically a very big deal.

In order to bring about the execution of Jesus, the religious authorities had to shift away from presenting Jesus as guilty of blasphemy to a political charge that he is a self-described king and therefore a threat to the authority of Caesar. The charge implied that Pilate, if he lets Jesus go free, will also suffer a political fallout.

So then the unthinkable happens. Pilate gives clemency a final effort, and the shift of the Sadducees from blasphemy to blackmail becomes the final word, and in pronouncing it, the Chief Priests commit a far greater blasphemy than the one they accuse Jesus of:

“Shall I crucify your king? The Chief Priests answered, ‘We have no king but Caesar.”

Then Pilate handed him over to be crucified.

+ + +

De Profundis: Pornchai Moontri and the Raising of Lazarus

The raising of Lazarus, the sixth of seven signs in the Gospel of St. John, is told “so that you may believe.” The raising of Pornchai Moontri is that story retold.

The raising of Lazarus, the sixth of seven signs in the Gospel of St. John, is told “so that you may believe.” The raising of Pornchai Moontri is that story retold.

Some very important things occurred on the day before I sat down to type this post. The day began for me at about 5:00 AM. I was alone in the dark, walking in silent solitude through the dew laden grass of the New Hampshire State Prison Ballfield. There was not another soul in sight. The day’s first light was but a hint of gray barely visible above the walls and razor wire. A few birds were stirring with the dawn’s early light, their song one of hope and serenity. I could smell the grass and the early morning air. All was beautiful. Succumbing to the hypnotic scene, I lay down in the beckoning grass and fell into a deep sleep.

And then I suddenly awoke from that dream to the harsh reality that ushers in my real day. The soft grass instantly transformed into cold concrete, the melody of songbirds into the snores of grown men, the smell of grass and the morning air into the stale and crowded confinement of what sometimes feels like a tomb.

I longed to drift back into my dream, but it was a luxury I could not afford that day. So I rolled over to the edge of my bunk, reached down to the floor, and plugged in a pot of water for coffee. Then I lay in the dark and placed before the Lord the important things of the day that lay before us.

A few minutes later, Pornchai-Max Moontri jumped down from his upper bunk and silently poured hot water into two cups of instant coffee. The other six denizens of our cell still slept as we prepared for a momentous day in prison. At 6:00 AM, Pornchai walked from our cell to a small bank of three telephones to place a long awaited call. For the first time since he was taken from his home and country at age 11 — 32 years ago — Pornchai placed a call to someone in Thailand. And it was not just ANY someone.

It was 6:00 PM in Thailand, and his first call to his homeland was to Yela Smit, a founding member of “Divine Mercy Thailand,” a group that reached across the world to embrace Pornchai with something he had once given up all hope for: a life beyond this long sleep of death in prison. This moment had its origin in one of the most compelling accounts of faith written at These Stone Walls, “Knock and the Door Will Open: Divine Mercy in Bangkok, Thailand.” Just how miraculous is that gift might be clearer below, but first, the story of Lazarus.

“I Have Come To Believe!”

Pornchai himself seemed to provide a prelude to the story of Lazarus. At Mass on the Fourth Sunday of Lent, he stood at the lectern to proclaim the Second Reading from the Letter of Saint Paul to the Ephesians. I found it difficult to distinguish the words from the life’s reality of the man proclaiming them:

“You were once darkness, but now you are light in the Lord. Live as children of light, for light produces every kind of goodness and righteousness and truth. Try to learn what is pleasing to the Lord. Take no part in the fruitless works of darkness, rather expose them, for it is shameful even to mention the things done by them in secret, but everything exposed by the light becomes visible, for everything that becomes visible is light. Therefore, it says ‘Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will give you light.’”

It amazes me how much those very words proclaimed by Pornchai-Max at Mass on the Fourth Sunday of Lent are both a summation of his life and a prelude to the raising of Lazarus in John 11:1-45. Pay special attention to this Gospel passage for the Fifth Sunday of Lent. Before we tell more, it needs a little background.

It was Winter in Jerusalem, and the Feast of the Dedication, the event known to us as Hanukkah. We began Lent at These Stone Walls this year with the background story of this Feast in “Semper Fi! Forty Days of Lent Giving Up Giving Up.” When Jesus went to the Temple at the time of this Feast (described in John 10:22-42), He was walking in the Portico of Solomon on the eastern side of the Temple mentioned in Acts of the Apostles 3:11.

Some of the Jews surrounded him, and challenged him about a circulating rumor that he is the Christ. They wanted him to claim it plainly, and they had taken up stones to execute him for blasphemy if he did. Storm clouds were gathering, and rumbling calls for his death were growing in Jerusalem.

Some Pharisees had been investigating his healing of a blind man on the Sabbath. They first thought the man had been faking his blindness, but witnesses attested that he had been blind from birth. They questioned the formerly blind man about the “sinner” who had healed him, but the man shot back, “Would God listen to a sinner?”

Now, at the Portico of Solomon in the Temple, Jesus spoke of his sheep hearing his voice. He challenged the Pharisees’ spiritual blindness, “If I am not doing the works of my Father, then do not believe me.” They took up stones and tried to arrest him, “but he escaped from their hands” (John 10:39). “The Hour of the Son of God” (the Seventh sign) had not yet come.

But then Jesus received word that Lazarus, the brother of Martha and Mary of Bethany, was ill. When Jesus heard this, he said, “This illness is not unto death; it is for the greater glory of God, so that the Son of Man may be glorified because of it.” Then he simply took his time, inexplicably letting two more days pass before departing to complete this sixth of seven signs in the Fourth Gospel’s “Book of Signs,” the raising of Lazarus from his tomb, the Gospel for the Fifth Sunday of Lent.

But first, what does the Fourth Gospel mean by its “Book of Signs?” Written in Greek, Saint John’s Gospel uses an interchangeable term – Sêmeion – for both “signs” and “miracles.” The Greek word is used sixty times through the New Testament, seventeen of them in the Fourth Gospel. Since the first six of the Gospel’s seven signs are found in Chapters one through twelve, this part of the Gospel is called “The Book of Signs.”

For this Evangelist, the signs of Jesus are mighty works, but they are also miracles told for a specific purpose. They are “signs” that lift a corner of the veil to point the readers’ gaze to the glory of God working through Christ. The signs of Jesus echo the signs of Moses during the Exodus from Egypt:

“And there has not arisen a prophet since in Israel like Moses, whom the Lord knew face to face, none like him for all the signs and wonders… and for all the mighty wonder and all the great and terrible deeds which Moses wrought in the sight of all Israel.”

The Sixth Sign, the raising of Lazarus, concludes the Book of Signs, and makes way for the rest of the Gospel and the Seventh Sign, the final and climactic sign — the Resurrection of Jesus — which Jesus elsewhere calls “The Sign of Jonah” (Matthew 12:39).

It is for this reason that the Church permanently chooses the Passion account from the Gospel According to Saint John for the proclamation of the Gospel on Good Friday. It is very different from the other three Gospel accounts. Here, the death of Christ is not just sacrifice and the path to redemption. It is also the moment of the enthronement of Christ the King upon the Cross. As the Seventh Sign, it is the fulfillment of the purpose of all the signs, in just the way that the Evangelist has Jesus presenting the illness of Lazarus: “To bring glory to God.” Martha, the sister of Lazarus, bridges the Sixth and Seventh signs in a dialogue with Jesus about the death of her brother:

“I am the resurrection and the life; he who believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live; and whoever believes in me shall never die. Do you believe this?’ She said to him, ‘Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, he who is coming into the world.’”

The Raising of Lazarus

Almost inexplicably in this Gospel account, once Jesus learns of the illness of Lazarus, he “stayed two days longer in the place where he was” (11:7). The account takes great pains to present that by the time Jesus arrives, Lazarus is not asleep or in a coma, but is dead, wrapped and bound in a burial shroud, and sealed in a tomb for four days. There can be no doubt.

The disciples are incredulous that Jesus would even think of going to Bethany in Judea where many of the Jews who had been in Jerusalem have now also gone. “Rabbi, the Jews were but now seeking to stone you, and you are going there again?” (John 11:8) The disciples totally misunderstand his reply — “If anyone walks in the day, he does not stumble.” Throughout the Fourth Gospel, Jesus is aware that until his “hour” comes, he can walk through all of Judea in safety. (We mined the depths of this “hour” in the Fourth Gospel in a Holy Week post, “Now Comes the Hour of the Son of God.”)

I found the response of Martha (above) to be perplexing at first: “I believe that you are the Christ, the Son of God, he who is coming into the world.” What could Martha mean by “coming into the world?” Jesus is already in the world. It’s a sort of presage of the events to come. Upon the cross, in sight of His mother and the Beloved Disciple, Jesus Himself becomes the Gate of Heaven. The raising of Lazarus is a preface to that event, and with the entire scene set, it is told in the simplest terms:

“‘Lazarus, come out!’ The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him, and let him go.’”

With those few words, the Fourth Gospel ends the Sixth Sign by ascribing to Jesus what was once for Israel the sole purview of Yahweh: the power over death, and life. From this point on in the Gospel of John, the Seventh Sign commences as the plot to put Jesus to death gets underway.

Another Chapter in Pornchai’s Story

There were chapters after this one awaiting in the future of Lazarus, but we will never know what they are. But this account echoes across the centuries, and still reverberates in countless lives of those called from death to life. Though Lazarus was physically dead, there is a parallel for those summoned forth from the tombs of spiritual death. One of them is our friend, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri, and his story is also told to unveil the glory of God.

I cannot tell all of it yet for some important chapters are still being written. But I can tell you this: the full account, when told, will be one of the most important Divine Mercy stories of our time. In the coming months, we hope to tell more of it, for the odds against any of it unfolding as they did are astronomical.

Pornchai’s recent telephone call to Thailand was but the latest step out of darkness into the light, and like Lazarus it leads only to his unbinding and new life. In 2009 when These Stone Walls began, we did not see this as even possible. Somehow, while buried in a prison cell in Concord, New Hampshire, we managed to tell a tale that circled the world, and when it came back around to us, it carried with it a multitude of good will and bonds of connection. For Pornchai, this tapestry of grace is still being woven, replacing the threads of only vague dreams and little hope with the powerful weaving of Divine Mercy. All has changed.

Among the instruments of that change is Viktor Weyand who is pictured in the photograph below with Pornchai Moontri. Viktor, an Austrian living in the United States, is a member of Divine Mercy Thailand and a founder of Divine Mercy School in Bangkok. During one of his many visits to Bangkok three years ago, he was asked to investigate the story of a young Thai man in an American prison in New Hampshire. That story drifted around the world from These Stone Walls. As happens among the hidden threads behind every tapestry of grace, Divine Mercy created bonds of connection that gathered strength and then rolled back the stone of Pornchai’s spiritual tomb. And as he put it, “I woke up one day with a future when up to then all I ever had was a past.”

The story of this other Lazarus is coming, and like the first, it will knock your socks off! For, now I can only give you once again the very words from Saint Paul that Pornchai read at Mass on the Fourth Sunday of Lent to open our hearts to the story of Lazarus:

“Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead. Christ will be your light.”

Editor’s Note: You might like these other journeys into the deeper threads of the Tapestry of God in Sacred Scripture from These Stone Walls:

Joseph’s Dream and the Birth of the Messiah

A Transfiguration Before Our Very Eyes

Casting the First Stone: What Jesus Wrote in the Sand

On the Road to Jericho: A Parable for the Year of Mercy

Upon the Dung Heap of Job: God’s Answer to Suffering

St Gabriel the Archangel: When the Dawn from On High Broke Upon Us

Angelic Justice: St Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed