“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

A Glorious Mystery for When the Dark Night Rises

At the dawn of the New Year, the Church honors the Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God. I met her at the age of nine, part lived experience and part dream.

At the dawn of the New Year, the Church honors the Solemnity of Mary, the Holy Mother of God. I met her at the age of nine, part lived experience and part dream.

January 1, 2025 by Fr Gordon MacRae

To comprehend this post, readers must understand the world of 1962. Something happened in America that dramatically changed our view of ourselves and the world around us, and its tentacles reach deeply into the present day. It brought a sense of futility, a resignation that we are powerless over the great tides of history sweeping us up into their grip, and resistance to evil is futile. So look out for Number One, and live for the moment! That is the great lie of our age.

I turned nine years old in April of 1962. Five months later, I began fifth grade a year younger than everyone else in my class. A month after that, the United States and the Soviet Union approached the very brink of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October, 1962. The administration of President John F. Kennedy discovered that the Soviet Union had placed strategic nuclear missiles in Cuba. Diplomacy failed miserably, and it just exposed our impotence. The United States demanded removal of the missiles and the Soviet Union flatly refused. President Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of Cuba. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev were all that stood between us and nuclear annihilation. Fear and deep anxiety engulfed everything — even the 5th grade.

Growing up in the industrial city of Lynn, Massachusetts, just a few miles north of Boston, left us especially vulnerable. Lynn at that time was home to the General Electric Company’s Aircraft Engine Division which was the largest employer in that city and surrounding towns. Its biggest customer was the U.S. military. Children my age were traumatized with fear by the weekly rehearsals for nuclear attack. Upon a signal from school administration we had to rush to extinguish all lights, draw all window shades and then crawl under our desks while sirens blared outside.

The day the Cuban Missile Crisis began, was the day our childhood innocence ended. We were vulnerable in a fragile, unpredictable world, and the anxiety never really left us. It was, perhaps in hindsight, the wrong moment for some of the great black-and-white science fiction films of the fifties to start running as matinees in a local cinema.

I did not understand then that some of those great films were really paradigms of the Cold War, containing within them all the fear and paranoia the Soviet Empire brought to our young minds. Films like “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” and — my favorite of all — “The Day the Earth Stood Still” are today considered Cold War classics. They captured our anxiety and capitalized upon our fears.

Invaders from Mars

I wrote of the North of Boston where I grew up in “February Tales.” Going to a movie theatre alone was a rare occurrence when I was nine years old in 1962. It meant venturing downtown like a free-range kid. Lynn, Massachusetts had two downtown cinemas back then, the Paramount and the Capitol. The latter was in Lynn’s Central Square, and it only opened at night — its marquee preceding every title with a large, mysterious “XXX.” It was strictly off limits.

It took a bit of courage back then for a 9-year-old to board a city bus alone for a Saturday afternoon trek downtown. I reveled in my freedom, but my parents had spies everywhere. When once I ventured too close to the Capitol marquee to see what all those Xs were about, there was hell to pay when I got home!

The Paramount had a Saturday matinee for 35 cents. Lynn’s newspaper, The Daily Evening Item carried an alluring ad, a miniature version of the movie poster for that week’s feature, “Invaders from Mars.” It portrayed a boy my age, aghast at his bedroom window by the scene of a spaceship landing at midnight in an empty field behind his house.

There was really no need for scary movies then. We were already all frightened enough, and those who claimed they were not were lying. But perhaps as kids we were all looking for outlets for our fear, because the real story of politics and nuclear bombs made no sense to us at all. Scary movies became the in thing, and I couldn’t wait to see “Invaders from Mars.”

Thirty-five cents for admission was no challenge at all then. There were always a few soda bottles to be found, and a little rummaging through the easy chair where my father watched a worried-looking Walter Cronkite every night yielded bus fare, and, if I was lucky, enough for that week’s special matinee snack, a Mars Bar.

It rained that Saturday, so just about every kid stuck inside was given bus fare to go see “Invaders from Mars.” The movie was preceded by a few cartoons to quiet us down, then it began. You could hear a pin drop. All the anxiety we had pent up within us was about to play out on the screen.

After the spaceship landed in that field, the boy in the film fell asleep. In the morning, he wondered whether it was all a dream. At breakfast, his mother and father and brother were acting very strangely. At school, his teacher and fellow students were strange, too. As he investigated, the story brought him to an underground tunnel where Martian zombies took direction from a squid-like mastermind managing the takeover of everyone’s mind and soul from its protected glass sphere. Those who today say there is really nothing to fear didn’t live through the Cold War and the Cuban Missile Crisis. I was utterly terrified.

When the movie was over and the lights came on, the older kids who had been throwing popcorn at us all disappeared into the streets. The kids in the middle, who were all my age, sat silently traumatized as the curtain closed. “Invaders From Mars” scared the &#§@ out of us! By the time I came to my senses all the kids I knew had scattered. None wanted to be seen in the fits of fright with which they departed “Invaders from Mars.”

Father G circa 1962.

A Glorious Mystery

Out on a rainy, darkened Union Street in downtown Lynn, I had missed the bus. It would be an hour before another came, and I had a sudden intense longing for the safety of home. So I set out on foot to walk the two miles through the city streets as it grew dark. Even today, when I am feeling vulnerable, anxious and alone, I dream of that trek at age nine through the city streets at night.

As I walked home on that day, my imagination raced ahead of me, and I felt fragile and alone. I was on the edge of tears for an accumulation of reasons I could never articulate. At times, the reality of feeling vulnerable strikes hard. I knew there were no evil Martian zombies, but I had an ill-defined sense that evil had just paid our world a visit and it changed us. We lived in a dangerous world, then, and since then its danger has exponentially grown.

And so on into the rain I walked. I walked alone, through a part of the city kids like me didn’t usually venture into. The darkness grew — both in the skies above me and deep, deep within me. You know what I mean for at one time or another, you have been there too. All light had gone out of the world. All hope had been drained away. Then the torrent came.

I’m not sure which soaked me more, the rain or the tears. I rarely cried as a boy — it was just hell if my older brother ever saw me crying — but the rain was making me shiver. I cannot ever forget that day. When I looked behind me in the dim darkness, someone was following me. A dark figure in a raincoat who stopped whenever I stopped. I tried to run, and when I did, he ran too.

There on the downtown city street, about a mile from the movie theatre, I came upon the imposing, looming spires of Saint Joseph Catholic Church. We didn’t spend much time in churches when I was growing up. The church’s dark brick façade and immensity seemed to stretch into the rumbling clouds. It felt almost as scary as “Invaders from Mars” and that ominous figure stalking somewhere behind me.

But the rain kept coming, and I had no choice. I climbed the steep marble steps of Saint Joseph Church, and just as I got to the top to duck into an alcove, a massive door opened next to me, and scared whatever wits I had left right out of me. It was, of all people, a police officer. I looked back down the street and the stalker had fled. “Get out of the rain, kid!” barked the officer as he shuffled me through the door on his way out. “And say a prayer for me while you’re in there,” he commanded. So in I went, almost against my will.

The church was massive. I had received my First Communion there two years earlier, but had never been back since. In the dim lights, I walked toward the sanctuary, and at the Communion rail, I knelt. I looked back toward the church doors, but no one had followed me in. I was alone, but a sense of safety slowly came over me. At some point it struck me that the police officer had come in here to pray and that thought impressed and comforted me. So I stayed for awhile.

Then I saw her! The great carved image in the sanctuary before me was crowned with light, and she held a child in her arms as though presenting Him to me. She was incredibly beautiful, but it was the creature beneath her feet that really gripped my attention and wouldn’t let it go. I stared in utter wonder at what was subdued beneath her feet. It was ugly, and all too real. It looked like the creature in the glass sphere that so terrified me in “Invaders from Mars.” It was trapped under her feet — under a soul that magnified the Lord.

Then the Martians left me. The stalker in the street left me. The missiles, and Khrushchev, and the Cold War left me. I felt, more than saw, the light come back into my world. The pulsing sobs, now still felt but unheard, left me, and a vista of hope broke through the clouds of doubt and fear. The look on her face was radiant, and she spoke to me. It wasn’t in words. It was deep, deep in the very place where fear had gripped my soul. I could not take my eyes from what was subdued beneath her feet. “Trust!” she said, and “Peace be with you.” And it was.

On that day she lifted me up out of a pit. Then years later, when once we met again, she humbled me, and I needed that, too. I tried to write about this in “Listen to Our Mother: Mary and the Fatima Century” but my words could not really ever do her justice.

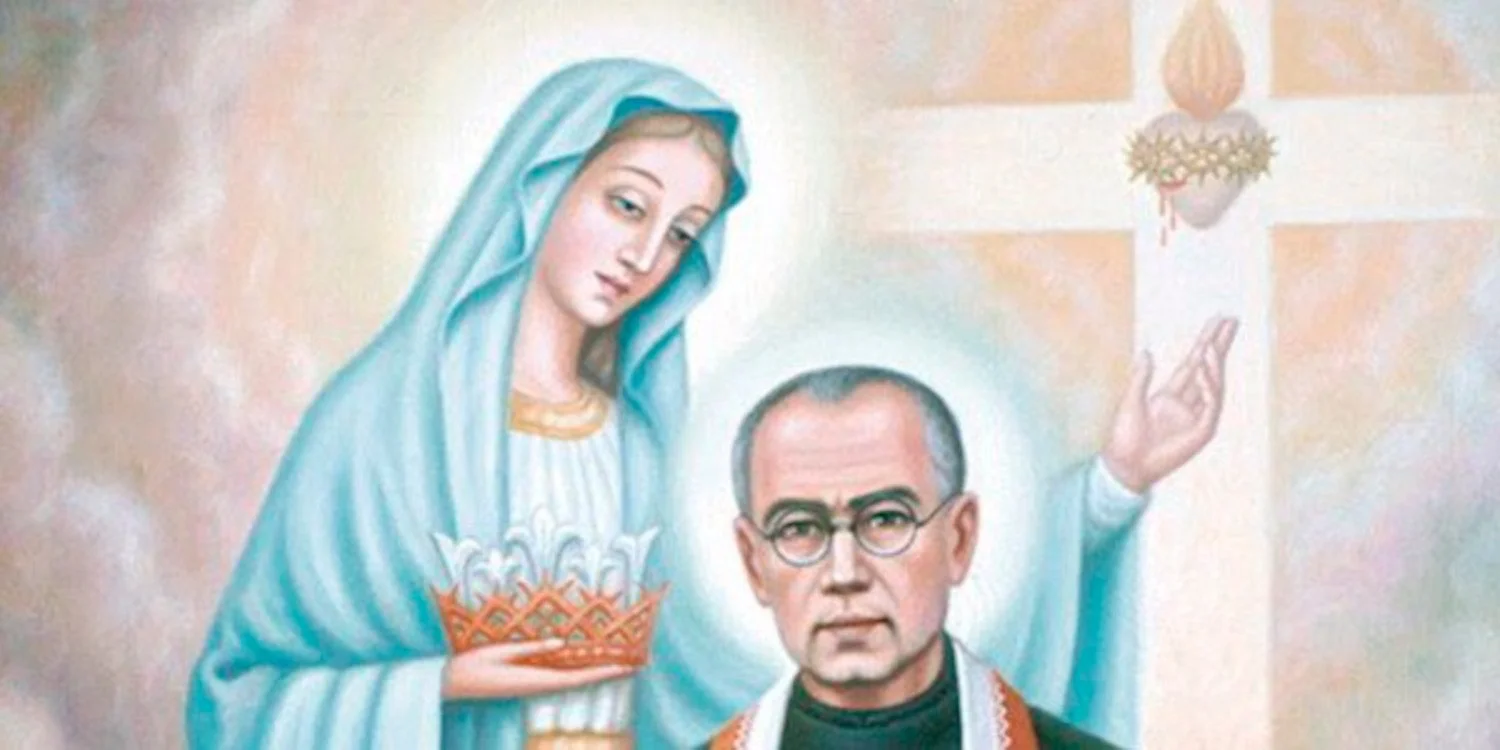

Sixty-two years have passed since that day. Well over a half century. On the wall of this prison cell is an image of Saint Maximilian Kolbe, the patron saint of prisoners and writers and the patron of Beyond These Stone Walls and this imprisonment. He’s Pornchai Moontri’s patron, too, and this changed everything for him. Saint Maximilian’s feast day is August 14.

Next to him on our cell wall is that image, the one I saw at age nine. I don’t know where it came from. It appeared one day in a letter to Pornchai and went quickly up onto his wall. I wrote once of the images on our cell wall in “Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed.”

Reason for hope is a very great gift. Never again let the sun go down on your fear. When the Glorious Mysteries seem too unworldly to fathom, then look beneath her feet. What is there will look very familiar to you, and you will know what it means. The key to resisting evil is trust that the strife may not yet be over, but the battle is already won.

Remember, O most gracious Virgin Mary,

that never was it known

that anyone who fled to your protection,

implored your help

or sought your intercession,

was left unaided.

Inspired with this confidence,

I fly unto you,

O Virgin of virgins, my Mother;

to you do I come,

before you I stand,

sinful and sorrowful.

O Mother of the Word Incarnate,

despise not my petitions,

but in your mercy hear and answer them.

Amen.

— The Memorare, by Saint Bernard of Clairveaux

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

How Our Lady of Fatima Saved a World in Crisis

The Assumption of Mary and the Assent of Saint Maximilian Kolbe

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

September 11, 2001, Freedom, Terrorism and Kamala Harris

The world was a dangerous place on September 11, 2001 and is now even more so. Freedom is shaken by terrorism and terrorism neither fears nor respects complacent joy.

The world was a dangerous place on September 11, 2001 and is now even more so. Freedom is shaken by terrorism and terrorism neither fears nor respects complacent joy.

September 11, 2024 by Fr Gordon J. MacRae

Eleanor Hodgman Porter was born in Littleton, New Hampshire in 1868. She wrote several novels with little notice, but at the start of World War One she wrote a blockbuster, Pollyanna. It became a world-wide bestseller that commonly came to be known as the Glad Book. It sparked a cultural phenomenon. It was about a girl, Pollyanna, whose ebullient personality met every evil and setback with a sense of glee and giddy happiness.

In the dismal years after World War I, “Glad Clubs” were inspired by it to reprogram young people into a perpetually happy state of mind no matter what ill confronted them. By the start of World War II, according to one reviewer, readers tired of Pollyanna’s laughing ‘hysterically,’ breathing ‘rapturously,’ and smiling ‘eagerly’ in the face of grave concern.

I watched much of the recent Democratic National Convention and was intrigued by it. I thought of Pollyanna all the way through it. It struck me as a half-time show in a Super Bowl game which had no connection to the battle at hand except to entertain. A state of perpetual joy cannot possibly reflect the realities of the dangerous world in which we live. Pollyanna and the Glad Book have mercifully vanished from our culture.

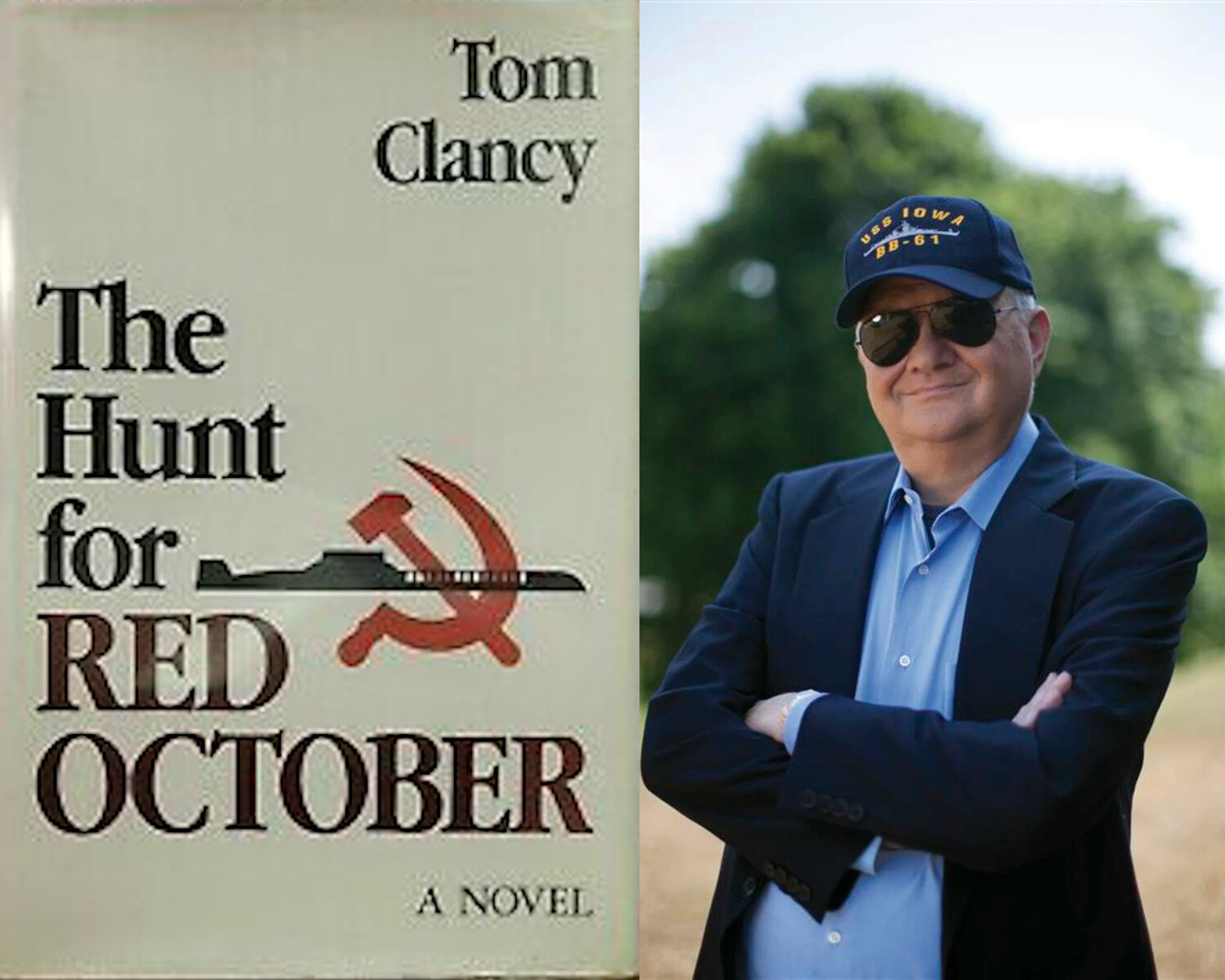

At Christmas in 1985, a young parishioner gifted me with a copy of Tom Clancy’s first novel, The Hunt for Red October. I was put off by its sheer volume and had no time to read it then. So I stuck it on a shelf in my parish office where it remained for months. Every time I saw the high school kid who gave it to me he asked me if I had read it yet. “You have to,” the young prophet insisted.

Then I read that President Ronald Reagan was reading that same book and described it as “unputdownable.” Many years and thousands of pages of Tom Clancy novels later, I wrote a tribute to the book and its author on the occasion of his untimely death in 2013. It was “Tom Clancy, Jack Ryan, and the Hunt for Red October.”

Most of my reading is done — even now — at the end of a busy day while lying flat on my back in bed with a book light. At this writing, nearly four decades after that first Clancy novel, I have devoured some 17,000 pages of his techno-thriller in the widely acclaimed “Jack Ryan” series. As time went on they got ever longer and more detailed, but I found each to be fascinating.

Clancy did a lot of research to bring realism to his novels. At times he would introduce a high tech fighter jet, for example, and devote 20 pages analyzing its technology. That drove some readers away, but it was what I loved most about his books. I made the big mistake once of referring to Clancy’s novels as “guy books.” Whoa, did I ever receive a thrashing from his many “non-guy” readers!

In 1994, I devoured 900 pages of Debt of Honor, Clancy’s eighth novel in the series. More than once, the big hardcover nearly broke my nose as I would read in bed until I could stay awake no longer. Then I would drop the book on my face.

By then, Jack Ryan had progressed through a distinguished and exciting career in the Central Intelligence Agency as a brilliant analyst and eventually as National Security Advisor. The riveting Debt of Honor ended with a spellbinding scene in Washington, DC as a Korean Airlines passenger jet was hijacked by Middle Eastern terrorists and flown at high speed by suicide bombers into the United States Capitol Building during a joint session of Congress wiping out most of the sitting U.S. government just as a new president was being sworn in.

History Repeats

Seven years later, on September 11, 2001, I relived that same scene with an intense sensation of déjà vu. Right before my eyes on national television, I watched live as the terrorist assault that came to be referred to simply as “9/11” unfolded before a shocked and unprepared free world. My first thought was to wonder whether the Clancy novel might have sparked such a framework of real terror into the minds of al Qaeda, but there was no such connection. I wrote of that day, its aftermath, and its challenges for the free world in “The Despair of Towers Falling, the Courage of Men Rising.”

Twenty-three years have now passed since that day, but everyone who was alive then, and at or near the age of reason, remembers it vividly. It became one of those iconic events of history in which everyone recalls not only the terror, but also a clear snapshot of where we were and what we were doing as that event unfolded. Tom Clancy instilled in me a high regard for history as a lens to the present. I have since digested 23 of Tom Clancy’s novels about foreign policy, its impact on history, or history’s impact on it.

It was a sequel to The Hunt for Red October that first drew me to the necessity of seeing the present with eyes that have gazed upon the past. September 11, 2001 did not happen in a vacuum. Clancy’s sequel, Cardinal of the Kremlin (Putnam, 1988) opened my eyes about Afghanistan. It was set toward the end of the Soviet Union’s decade-long occupation of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989, and the struggle of the Afghan people to be rid of that occupying force. The Taliban were never mentioned there, nor were al Qaeda, Islamic State, or ISIS-K. None of them existed yet, but the seeds of all of them were firmly planted and flourishing in Afghanistan as a result of that decade and all that followed. It is important to know this.

On Christmas Day, 1979, Soviet forces invaded Afghanistan. They quickly won control of the capital, Kabul, and other important cities. The Soviets executed the Afghan political leader and installed in his place a puppet government led by a faction more amenable to Soviet control. Wide rejection of that government by the Afghan people led to civil war. A Saudi Arabian multimillionaire named Osama bin Laden established a training camp in the mountains of Afghanistan for rebels fighting the Soviet forces.

The 1980s also saw increased friction between the United States and the Soviet Union resulting from the 1979 invasion and occupation of Afghanistan. President Ronald Reagan, elected in 1980, greatly increased American military capabilities. The Soviets viewed him as a formidable foe committed to subverting the Soviet system. In his 1985 State of the Union address, President Reagan called the Soviet Union an “Evil Empire,” and vowed to root out and destroy any political movements that supported it.

In the mid-l980s, resistance to the Communist government and the Soviet invaders grew throughout Afghanistan. Some ninety regions in the country were commanded by guerrilla leaders who called themselves “mujahideen,” meaning “Muslim holy warriors.” The mujahideen resented the Soviet presence and its puppet government. By the mid-1980s the U.S. was spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year to aid these Afghan rebels based in Pakistan in a war to expel the Soviet occupation which took the lives of some 1.3 million Afghanis in their struggle.

Then in 1989, the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan leaving in their wake a leadership vacuum in a country wracked by civil war. From a distance over the decade to follow, the United States continued to provide funds and weapons to the mujahideen rebels. Afghanistan was now without solidifying leadership, and nature abhors a vacuum.

The Taliban

From the rubble of war, chaos, and a rudderless nation, the Taliban were born. The Taliban movement was created in 1994 in the southern Afghan city of Kandahar by Mohammed Omar, a senior Muslim cleric (called a mullah) . The name, “Taliban” simply means “student.” It refers to the movement’s roots in the fundamentalist Islamic religious schools in Pakistan. For many youth in this war-torn nation, religious indoctrination was the only education they received.

Even that limited education was available only to young men. As the Taliban rose to power in 1994 imposing strict Islamic fundamentalism on the nation, secondary schools for girls were closed and girls were barred from receiving any education beyond a grade school level. Music and dancing were banned outright. Public works of art were destroyed. I once wrote in these pages of an infamous example. In 2001, just as Osama bin Laden was deep into a plot against the United States, the Taliban drew attention away by blowing up a 180 foot stone statue of Buddha that had been carved into an Afghan mountainside 1500 years earlier.

Many of the Taliban laws alarmed human rights groups and provoked worldwide condemnation. The Taliban strictly enforced ancient customs of purdah, the forced separation of men and women in public. Men were required to grow full beards. Those who did not comply, or could not, were subjected to public beatings. Women were required to be covered entirely from head to toe in burkas while in public view. Those who violated this were often beaten or executed on the spot by Taliban religious police. Women were also forbidden from working outside the home. With thousands of men lost to war, many widows and orphans lived in dire poverty.

As the Taliban movement grew in size and strength, it recruited heavily from the mujahideen, the anti-Soviet freedom fighters who were funded and armed in part by the United States. The Taliban gave a new national identity to the thousands of war orphans who were educated in only two fields of study: strict fundamentalist Islamic interpretation of the Quran, and war. The young men of Afghanistan became radicalized.

The Rise of Al Qaeda

Most other countries did not recognize the Taliban as a legitimate government, thus further isolating Afghanistan and its people from oversight and connection in the world community. From their pinnacle of power, the Taliban provided safe harbor to Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda, formed in 1980s Afghanistan to help repel the Soviet invasion and incite a global holy war called, in Arabic, a jihad. The term, al Qaeda is Arabic for “base camp.” For its founder and adherents, it would become the base from which worldwide Islamic revolution and domination would be launched. We entered Afghanistan after 9/11 for that reason. It had become the host and incubator for terrorist actions against the United States. When we withdrew suddenly in 2021 we left behind that incubator, still festering with hatred from Islamic extremists.

Over the course of the Soviet occupation from 1979 to 1989, Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda trained, equipped, and financed 50,000 mujahideen warriors from 50 countries. Saudi Arabian nationals comprised more than fifty percent of the recruits. Saudi Arabia’s strict interpretation of Islam motivated many young men to come to the defense of Afghanistan and the Muslim world against Western “infidel” influences.

When the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989, Osama bin Laden returned to his original goal for al Qaeda: to overthrow Muslim or Arab regimes that he considered too weak and tolerant of Western influence. Bin Laden envisioned replacing these regimes with a single Muslim empire organized around Islamic “Sharia” law. He targeted the United States and other Western nations because he saw them as obstacles to his cause by becoming political allies with Muslim nations he considered to be corrupt.

From 1991 to 1996, with the Taliban in control of Afghanistan, bin Laden quietly built al Qaeda into a formidable international terrorist network with cells and operations in 45 countries. Training camps were established in Sudan, and by 1992 most of al Qaeda’s operations were relocated there. From that base, attacks on U.S. troops and U.S. interests were launched in Yemen and Somalia and at a joint U.S.-Saudi military training base in Saudi Arabia. Osama bin Laden was especially angered by the mere existence of that base.

Bowing to pressure from the Saudi and U.S. governments, al Qaeda and bin Laden were expelled from Sudan in 1996 and returned to Afghanistan where they were free to plot. He formed a mutually beneficial relationship with the Taliban while plans for a direct assault on the United States took shape. The September 11, 2001 attacks, which killed over 3,000 Americans on U.S. soil, thus came together while the world was not watching.

In response, the United States declared war on terrorism, the first declaration of war against a concept instead of a country. While Taliban leaders rejected U.S. demands to surrender bin Laden, the U.S. began aerial bombings of terrorist training camps and Taliban military positions in October, 2001. Ground troops of the Northern Rebel Alliance in Afghanistan rebelled and maintained a front-line offensive against Taliban forces with help in the form of funds and weapons from the United States.

Al Qaeda’s attack on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon began on September 11, but it was not September 11, 2001. This is where failures of national intelligence and readiness are crucial factors. The September 11 date for terrorist assaults on the United States was not random. For extremists in the Muslim world, the next day, September 12, was a day of infamy, a day of reckoning for a 17th Century Islamic assault on Europe.

The Muslim command captured and slaughtered 30,000 hostages. This caused Polish King Jan Sobieski to meet the assault with the largest volunteer infantry army ever assembled. The Muslim push for control of Eastern Europe was stopped in its tracks on September 12, 1683. What we call 9/11 was the result of an Islamic grudge held for over 300 years.

Jesus said (Luke 10:3) “Go your way; behold, I send you out as lambs in the midst of wolves.” Lambs in the midst of wolves are ever vigilant, and they count on a shepherd who will not lead them into slaughter. The last four years have seen a disastrous policy that left the U.S. southern border open with little oversight. I would want my country to welcome refugees and care for them. That is clearly called for in the Gospel. But among the nearly 11 million who have crossed that border undetected are al Qaeda and ISIS-K operatives lying in wait to unleash their terror upon the United States. In a world at the cusp of war, the threats have never been more dire.

As much as we might like Pollyanna, and revel in her smile, are we really prepared to make her Commander in Chief of U.S. Armed Forces?

+ + +

Note from Fr Gordon Mac Rae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls :

Tom Clancy, Jack Ryan, and the Hunt for Red October

The Despair of Towers Falling, the Courage of Men Rising

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

A Tale of Two Priests: Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul II

St. Maximilian Kolbe was a prolific writer before his arrest by the Gestapo in 1941. He died a prisoner of Auschwitz, but true freedom was his gift to all who suffer.

St. Maximilian Kolbe was a prolific writer before his arrest by the Gestapo in 1941. He died a prisoner of Auschwitz, but true freedom was his gift to all who suffer.

“There is no greater love than this, that a man should lay down his life for his friends.”

— John 15:13

August 10, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

In his wonderful book, Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn’t, and Why (Touchstone 1990), author and former Newsweek editor Kenneth L. Woodward wrote that the martyrdom of St. Maximilian Kolbe was one of the most controversial cases ever to come before the Vatican Congregation for the Causes of Saints.

The essential facts of Kolbe’s martyrdom are well known. After six months as a prisoner of Auschwitz in 1941, Maximilian and the other prisoners of Cell Block 14 were ordered outside to stand at attention for commandant Karl Fritzch. Someone from the block had escaped. To encourage informants, the Commandant had a policy that ten men from the cell block of any escaped prisoner would be chosen at random to die from starvation, the slowest and cruelest of deaths.

The last to be chosen was Francis Gajowniczek, a young man who collapsed in tears for the wife and children he would never see again. Another man, Prisoner No. 16670, stepped forward. “Who is this Polish swine?” the Commandant demanded. “I am a Catholic priest,” Maximilian Kolbe replied, “and I want to take the place of that man.” The Commandant was speechless, but granted the request. Maximilian and the others were marched off to a starvation bunker.

For the next 16 days, Kolbe led the others in prayer as one by one they succumbed without food or water. On August 14, only four, including Maximilian, remained alive. The impatient Commandant injected them with carbolic acid and their bodies were cremated to drift in smoke and ash in the skies above Auschwitz. It was the eve of the Solemnity of the Assumption. God was silent, but it only seemed so. I wrote about this death, its meaning, and the cell where it occurred in “Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance.”

If that event summed up the whole of Maximilian’s life, it may seem sufficient to be deemed heroic virtue. Today, the name of the brutal Commandant Karl Fritsch is forgotten from history while all the world knows of Maximilian Kolbe, and for far more than his act of sacrifice for someone he barely knew. His act of Consecration to Jesus through Mary was well known long before the Nazi occupation of Poland in 1939. As the occupation commenced, Maximilian had a readership of over 800,000 in Poland alone for his monthly magazine, Knights of the Immaculata.

Perceived as a clear threat to the Nazi mindset, he was arrested and jailed for several months in 1939 while his publishing ability was destroyed. Upon his release, he instituted the practice of round-the-clock Eucharistic Adoration for his community decades before it became common practice in parishes.

The Nazi occupiers of Poland were the cruelest foreign rulers in history. A detailed report on conditions of the Nazi occupation compiled and smuggled out of Poland by Catholic priests was made public in Vatican City in October 1941. More than 60,000 Poles were imprisoned in concentration camps, 540,000 Polish workers were deported to forced labor camps in Germany where another 640,000 Polish prisoners of war were also held.

By the end of 1941, 112,000 Poles had been summarily executed while 30,000 more, half of those held in concentration camps, died there. Famine and other deplorable conditions caused a typhus epidemic that took many more lives. By the end of the Nazi terror, six million Jews — fully a third of European Jews — had been exterminated. There are those whose revisionist history faulted the Vatican for keeping silent, but that was not at all the truth. I wrote the real, but shocking truth of this in “Hitler’s Pope, Nazi Crimes, and The New York Times.”

Karol Wojtyla

These were also the most formative years for a man who would one day become a priest, and then Archbishop of Krakow in which Auschwitz was located, and then Pope John Paul II. In 1939 as the Nazi occupation of his native Poland commenced, 18-year-old Karol Wojtyla found his own noble defiance. Over the next two years he worked in the mines as a quarryman, and at the Solvey chemical plant while he also took up studies as part of the clandestine underground resistance.

In the fall of 1942, Karol Wojtyla was accepted as a seminarian in a wartime underground seminary in the Archdiocese of Krakow. Two years later, a friend and fellow seminarian was shot and killed by the Gestapo. The war and occupation were a six-year trial by fire in which young Karol was exposed to a world of unspeakable cruelty giving rise to unimaginable heroism.

One of the stories that most impacted him was that of the witness and sacrifice of Father Maximilian Kolbe. He became for Karol the model of a man and priest living the sacramental condition of “alter Christus,” another Christ, by a complete emptying of the self in service to others. In scholarly papers submitted in his underground seminary studies, Karol took up the habit of writing at the top of each page, “To Jesus through Mary,” in emulation of Maximilian Kolbe.

On November 1, 1946, on the Solemnity of All Saints, Karol Wojtyla was ordained a priest in the wartime underground seminary. He was the only candidate for ordination that year. Two weeks later, he boarded a train for graduate theological studies in Rome where, like Maximilian Kolbe before him, he would obtain his first of two doctoral degrees. It was the first time he had ever left Poland.

In 1963, he was named Archbishop of Krakow by a new pontiff, Pope Paul VI. It was alive in him in a deeply felt way that he was now Archbishop of the city of Sister Faustina Kowalska, the mystic of Divine Mercy who died in 1938 and whose Diary had spread throughout Poland having a deep impact on young Karol Wojtyla. And he was Archbishop of the site of Auschwitz, of the very place where the Nazi terror occurred, the place where Maximilian Kolbe offered himself to save another.

I was ten years old the year Karol Wojtyla became Archbishop of Krakow. I was 25, and in my first-year of theological studies in seminary when he became Pope John Paul II. In June of 1979, he made his first pilgrimage as pope to his native Poland. This visit marked the beginning of the collapse of the Soviet Union and European Communism. During his pilgrimage, Pope John Paul visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration and extermination camps. He knelt on the floor of Block 11, Cell 18 at the very spot in which Maximilian Kolbe died. John Paul kissed the floor where Kolbe had prayed in agony 38 years before. He left there a bouquet of red and white roses, an act with great significance that I will describe below.

When Pope John Paul emerged from his veneration in the starvation cell that June day in 1979, he embraced 78-year-old Franciszek Gajowniczek whose life Maximilian had saved by taking his place in death. I remember this visit. It was the first time I had ever heard of Maximilian Kolbe. I would next hear of him again when he was canonized in 1982, the year of my priesthood ordination. Neither event was without controversy. I recently wrote of my own in “Forty Years of Priesthood in the Mighty Wind of Pentecost.”

A Martyr in Red and White

But the controversy around the canonization of St. Maximilian Kolbe is much more interesting. It actually changed the way the Church has traditionally viewed martyrdom. Maximilian’s sacrifice of himself at Auschwitz was a story that spread far beyond Catholic circles. In his book, People in Auschwitz, Jewish historian and Auschwitz survivor, Hermann Langbein wrote:

“The best known act of resistance was that of Maximilian Rajmond Kolbe who deprived the camp administration of the power to make arbitrary decisions about life and death.”

In 1971, the beatification process for Maximilian presided over by Pope Paul VI was based solely on his heroic virtue. Two miracles had already been formally attributed to his intercession. Shortly after the beatification, Pope Paul VI received a delegation from Poland. Among them was Krakow Archbishop Karol Wojtyla. In his address to them, Pope Paul VI referred to Kolbe as a “martyr of charity.”

This rankled the Poles and even some of the German bishops who had joined the cause for Maximilian’s later canonization. They wanted him venerated as a martyr. Strictly speaking, however, it did not appear to Paul VI or to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, that Maximilian was martyred for his faith, traditionally the sole standard for declaring a saint to also be venerated as a martyr. Pope Paul VI overruled the Polish and German bishops.

The next Pope, John Paul II, had for a lifetime held Maximilian Kolbe in high regard. In order to resolve the question of martyrdom, he bypassed the Congregation for the Causes of Saints and appointed a 25-member commission with two judges to study the matter. The Commission was presided over by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, who would later become Pope Benedict XVI.

In the end, on November 9, 1982, the Mass for Canonization of St. Maximilian Kolbe took place at St. Peter’s Basilica before a crowd of 250,000, the largest crowd ever in attendance for a canonization. At the Mass, Pope John Paul II proclaimed:

“And so, in virtue of my apostolic authority I have decreed that Maximilian Maria Kolbe, who after beatification was venerated as a confessor, shall henceforth also be venerated as a martyr.”

The matter was officially settled. Maximilian Kolbe became a saint canonized by a saint. But it was really settled in the mind of John Paul three years earlier on the day when he laid a bouquet of red and white roses on the floor of the Auschwitz starvation cell where Maximilian died.

It was an echo from Maximilian’s childhood. At around the age of ten in 1904, Rajmond Kolbe was an active and sometimes mischievous future saint. He was obsessed with astronomy and physics, and dreamed of designing a rocket to explore the Cosmos. He exasperated his mother, a most ironic fact given his lifelong preoccupation with the Mother of God. One day, his mother was at her wit’s end and she scolded him in Polish, “Rajmond! Whatever will become of you?”

Rajmond ran off to his parish church and asked his “other” Mother the same question. Then he had a vision — or a dream — in which Mary presented him with two crowns, one dazzling white and the other red. These came to be seen as symbols for sanctity and martyrdom, and they were the source for Pope John Paul’s gesture of leaving red and white flowers at the place where Maximilian died.

Epilogue

I witnessed firsthand a similar experience involving the conversion of my friend, Pornchai Moontri who took the name, Maximilian, as his Christian name. He may not have been aware of his mystical heart to heart dialog with the patron saint we both shared. Pornchai is a master woodworker, a skill he has not been able to utilize yet in Thailand because organizing a work place and acquiring tools is a major undertaking.

Around the time of our Consecration to Jesus through Mary, an event I wrote of in “The Doors that Have Unlocked,” Pornchai took up a project. He had perfected the art of model shipbuilding and decided to design and build a model sailing ship named in honor of his Patron Saint. He called it “The St. Maximilian.”

Pornchai chose black for the ship’s hull, but on the night before completing it he had an insight that he had to paint the hull red and white. When I asked him why, he had no explanation other than, “It just seems right.” He could not have known about Maximilian’s childhood vision of the red and white crowns or Pope John Paul’s gesture at Auschwitz.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: This story is filled with irony and coincidence, none of which is really coincidence at all. It is summed up in this quote from St. Maximilian Kolbe, which was sent to me just before I wrote this post:

“For every single human being God has destined the fulfillment of a determined mission on this earth. Even from when he created the Universe, he so directed causes so that the chain of events would be unbroken, and that conditions and circumstances for the fulfillment of this mission would be the most appropriate and fitting.

“Further, every individual is born with particular talents and gifts (and flaws) that are applicable to, and in keeping with, the assigned task, and so throughout life the environment and circumstances so arrange themselves as to make possible the achievement of the goal and to facilitate its unfolding.”

— St. Maximilian Kolbe

Another note from Fr. G: The above quote was found on a bulletin from the National Shrine of St. Maximilian Kolbe in Libertyville, Illinois. It was sent from an unusual source, a retired F.B.I. Special Agent was attending Adoration at the Shrine when he spotted the quote and decided to send it to me. He also sent the message below, which will serve as the first comment for this post.

“During the third week of January of this year, I attended Adoration and the Noon Mass at Marytown, Libertyville, Illinois where The National Shrine of Saint Maximilian Kolbe is located and received a copy of the Marytown Church bulletin. The Shrine is under the sponsorship of the Conventual Franciscan Friars – the religious order that St. Maximilian was a member of. St Maximilian Kolbe was put to death at Auschwitz concentration camp on August 14, 1941 and was ‘cremated’ the next day on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary into Heaven. He is the patron saint of various groups but perhaps most notably known for being the patron saint of prisoners. Marytown is very much involved in ministry to prisoners throughout the United States by providing Catholic material to Chaplains of prison facilities and other outreach activities.

“The day after this particular visit to Marytown, I was reading the online Catholic League newsletter and saw information about the ‘Laurie List’ and how it pertained to the trial and incarceration of Fr. Gordon MacRae. The Laurie List was evidently a ‘secret’ list of New Hampshire police officers accessible to prosecutors, who had issues arise questioning their truthfulness and veracity. Any issue that arises as to the truthfulness of a witness particularly a police officer is supposed to be made known to the defendant and his attorney. The Keene NH detective who investigated the case against Fr. Gordon is on this list. If ‘impeachable’ information regarding this detective was known, this information should have been made available to Fr. Gordon and his defense attorney. I have been following Fr. Gordon’s situation for a number of years and so I am aware of his devotion to St. Maximilian Kolbe.

“After reviewing rules to send mail to the prison housing Fr. Gordon in Concord, New Hampshire, I forwarded the weekly bulletin to him which usually quotes a passage from the writings of St. Maximilian. This has led to a correspondence and receiving Father’s weekly post. Those familiar with Father’s website — Beyond These Stone Walls — are aware of Pornchai Moontri, his tragic life, long period of incarceration, transfer to the NH prison in Concord, becoming the cellmate of Fr. Gordon, Pornchai’s entrance into the Catholic Church — taking a baptismal name of Maximilian — and his ultimate release from prison. I currently try to assist Fr. Gordon’s work (his web site, assistance to Pornchai, etc.) through prayer and financial support.”

One last note from Fr. G: Please visit our “Special Events” page for an update on ways that you can help sustain Beyond These Stone Walls.

Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You may also wish to visit these related posts:

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance

Independence Day in Thailand by Pornchai Maximilian Moontri

It Is the Duty of a Priest to Never Lose Sight of Heaven

Marking 39 years of priesthood, 27 of them unjustly in prison, this priest guides readers to higher truths. For those who suffer in life, eternal life matters more.

Marking 40 years of priesthood, 28 of them unjustly in prison, this priest guides readers to a higher truth. For those suffering in life, eternal life matters more.

“When suffering is far away, we feel that we are ready for everything. Now that we have occasion to suffer, we must take advantage of it to save souls.”

I am indebted to my friend, Father Stuart MacDonald, JCL, for his remarkable and timely guest post, “Bishops, Priests, and Weapons of Mass Destruction.” In it, he concluded that some of our bishops have acted in regard to their priests by caving into the cancel culture mob even before it was called that. “The mob can be a frightening place when we have lost sight of heaven,” he boldly wrote. I was struck by this important insight which lends itself to my title for this post: It is the duty of a priest to never lose sight of heaven.

In the weeks before I mark forty years of priesthood, I have heard from no less than three good priests who have been summarily removed from ministry without a defense. Like many others, they are banished into exile following 30-year-old claims for which there exists no credible evidence beyond the accusations themselves and demands for money.

This sad reality, imposed by our bishops in a panicked response to the Catholic abuse crisis, has been the backdrop of nearly half of my life as a priest. As Father Stuart mentioned in his post, I wrote of this a decade ago in regard to the demise of the celebrated public ministry of Father John Corapi at EWTN. Given the resurgence of priests falsely accused, I decided to update and republish that post on social media. It is “Goodbye, Good Priest! Fr. John Corapi’s Kafkaesque Catch-22.”

The point of it was not Father Corapi himself, but rather the matters of due process and fundamental justice and fairness that have suffered in regard to the treatment of accused priests. In republishing it, I was struck by how little has changed in this regard since I first wrote of Father Corapi a decade earlier.

My article presents no new information on the priesthood of Father Corapi, but lest our spiritual leaders think that interest in this story among Catholics has diminished, within 24 hours of publishing, that post was visited by over 6,500 readers and shared on social media 3,700 times. (Note: We now give it a permanent home in the “Catholic Priesthood” Category at the BTSW Library.)

The only priests who land in the news these days are those accused of sexual or financial wrongdoing and those who make their disobedience to Church authority in matters of faith and morals a media event. In regard to the latter, several priests and bishops in Germany have openly defied Pope Francis and his decision to bar priests from blessing same-sex unions.

Blessing the individuals involved would not be an issue, but, as Pope Francis put it, “The Church cannot bless sin.” The open defiance of this among some German priests brought them 15 minutes of fame in our cancel culture climate in recent weeks, but it does nothing to bring us any closer to heaven.

Appearing on The World Over with Raymond Arroyo recently, Catholic theologian and author, George Weigel, addressed the German situation plainly:

“These bishops think that they know more about marriage than Jesus, that they know more about worthiness for the Eucharist than Saint Paul. This is apostasy, and it is time to call it what it really is.”

The Setting for My Priesthood

In every age, people tend to see the struggles of their current time as the worst of times. My priesthood ordination took place on June 5, 1982. It was the only ordination in the Diocese of Manchester, New Hampshire that year. President Ronald Reagan was in the second year of his first term in office. The U.S. economy was suffering its most severe decline since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Unemployment was at its highest level in decades and the housing industry was on the verge of collapse.

Just over a year earlier, on May 13, 1981, Pope John Paul II was shot four times at close range as he entered Saint Peter’s Square to mark the 64th anniversary of the first appearance of Our Lady of Fatima in Portugal. John Paul was severely wounded and so was the spirit of the global Catholic Church. He recovered, though a lesser man might not have.

One year later, three weeks before my ordination, Pope John Paul made a thanksgiving visit to Fatima on May 12, 1982. It was the day before the anniversary of both the Visions of Fatima and the attempt on his life. As the Pope walked toward the altar of the Fatima shrine, a man in clerical garb lunged at him with a bayonet, coming within inches of killing John Paul before being subdued by security guards.

The assailant was Juan Fernandez y Krohn, then age 32, a priest ordained by the suspended traditionalist French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. Fernandez was subsequently expelled from Lefebvre's movement. As he lunged at the Pope with his bayonet, he shouted in denouncement of the Second Vatican Council while accusing Pope John Paul of collaborating with the dark forces behind the spread of Communism.

That latter accusation was highly ironic. Over the next decade, Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul II collaborated to become the two major forces behind the collapse of the Soviet Union and European Communism that had held the Western World in the grip of Cold War since the end of World War II.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall was torn down by a crowd of citizens from both East and West as soldiers watched in silence. On Christmas Day, 1991, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev announced his resignation in a television address. The next day, the Soviet parliament passed its final resolution ratifying the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Within a week, all residual functions of the Soviet Communist state ceased. The USSR was no more, thanks to the strength and fidelity of a Pope and a President.

The footprints of Ronald Reagan and Pope John Paul on modern human history are immense. This and the chaos of the world at that time formed the backdrop against which I became a priest in 1982. I wrote of this in “Priesthood: The Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times.”

The sins of the times were many. On the world stage, Pope John Paul courageously confronted the Marxist “cancel culture” movement of his time. His bold witness to the world and his fidelity are highlighted in a new and important book by George Weigel entitled Not Forgotten.

In contrast, much of the current Catholic ecclesial leadership seems bogged down in demonstrations of tolerance for dissent and the rise of socialism and Marxist ideology that again springs up anew as “cancel culture.” Some bishops cannot even decide whether open promotion of abortion should bar its adherents who are nominally Catholic from presenting themselves for the Eucharist.

Ironically, recent polls have suggested that 66-percent of American Catholics are uncertain whether they still even believe in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. It is that exact same percentage who also believe that President Biden should be admitted to the Eucharist without question despite his open promotion of abortion as a civil right. Our Catholic crisis is not just one of fidelity. It is a crisis of identity. But as has been famously asked by another well-known priest, “Who am I to judge?”

Witnessed in a Prison Journal

Now here I stand, 39 years into my priesthood on the peripheries with 27 of those years in wrongful imprisonment for abuse claims that never took place. I could have left prison 26 years ago had the truth meant nothing to me. I have been reading the far better known story of another falsely accused priest in the Prison Journal of George Cardinal Pell published by Ignatius Press.

I find in it much solace and peace. I am strengthened in my priesthood by the great effort of Cardinal Pell to maintain his identity as a priest even in prison. I know from long experience - too long - that there is nothing in prison, absolutely nothing that sustains an identity of priesthood. It is so easy and a constant temptation to simply give up. For page after page in the Journal, I find myself thinking, “I felt that very same way,” or “I did these very same things.” Our prisons were similar, although from Cardinal Pell descriptions, Australia’s prisons seem a bit more humane.

Cardinal Pell was in prison for 400 days before his unjust convictions were recognized as such in a unanimous exoneration by Australia’s High Court. On my 39th anniversary of ordination on June 5th this year, I mark 9,750 days in wrongful imprisonment. I do not point this out to contrast my experience with that of Cardinal Pell. His ordeal, like mine, was defined by his first failed appeals after which he had every reason to believe that prison could thus define the rest of his life.

I have no known recourse because, unlike Australia, the United States courts have given greater weight to states’ rights to finality in criminal cases than to innocent defendants’ rights to a case review. When I had new witnesses and evidence, the court not only declined to hear it, but declined to allow any further appeals. We even appealed that, but to no avail.

But a distinction between justice for Cardinal Pell and for me is not the point I want to make. I felt the lacerations to his good name in every step of his Way of the Cross as news media in Australia and globally exploited the charges against him. What a trophy his wrongful conviction was for those who hate the Church!

I felt the scourging he endured as multiple false claimants tried to use his cross for financial gain. I felt his condemnation in the halls of the high priests as cowardly men of the Church denounced him, at worst, or at best stood speechless in the shadows of silence, rarely mentioning his name, and even then only in whispers.

Reading Volume One of Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal has been both consoling and distressing. Consoling in that when all else was stripped away, truth and priesthood, even more than freedom, were still at the heart of this good priest’s identity. The measure of a man is not when all is going well, but when all that is dear and familiar has been stripped away. Cardinal Pell held up well. I like to think I have, too.

I have reserved a copy of Volume Two of the Prison Journal. I am told by those who know that in a few of its pages, Cardinal Pell also wrote about me. That struck me as highly ironic in that I wrote several times about his plight, the last being “From Down Under, the Exoneration of George Cardinal Pell.”

And by “From Down Under,” I do not just mean Australia!

The Last Years of My Priesthood

I expect that I will die in prison. This is not a statement out of despair. No one has taken my faith in Divine Providence and Divine Mercy. There came a time in my imprisonment when I recognized a pattern of grace that began with the insinuation of Saint Maximilian Kolbe into my life as both a priest and a prisoner. This grace has been profound, and staggering in its visibility and power. Our readers — all but the most spiritually blind — have seen it.

After a lifetime of devoting himself as a priest in Consecration to Jesus through Mary, Maximilian coped with his suffering as grace rather than torment. This story culminated, as you know, in his spontaneous decision to surrender his life so that another could live. This act of sacrifice has long been heralded as an exemplar of the words of Jesus, “No greater love has a man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

There came a point in my imprisonment when it was clear that all I tried to do to bring about justice was in vain. So I asked for Divine Mercy and the ability to find grace in this story. A life without grace is far worse than a life without justice. It was at that very point at which my friend, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri, arrived upon my road as a priest. He had been mercilessly beaten down in life, and robbed of all trust and hope.

I could have been the priest who saw him on that road and passed him by like the priest in the Parable of the Samaritan. But I stopped, and when I learned the whole truth of his life, I set my own hope for justice aside. It became clear to me that this was God’s action in my life and a task that He has given only to me. It became clear that Pornchai has a special connection to Christ through the Immaculate Heart of Mary and I was to be his Saint Joseph.

I wrote a post about this healing mission which I contrasted with the Book of Tobit and the mission of Saint Raphael the Archangel to be God’s instrument of healing. I wrote of this in one of my own favorite posts at Beyond These Stone Walls in “Archangel Raphael on the Road with Pornchai Moontri.”

You should not miss that post, and if you do read it, you would do well to ponder for awhile the mysteries of grace on your own life’s path. It was well after writing and posting it that I learned something that stunned me into a better awareness of the irony of grace.

Over the course of time, the Church has devised a Lectionary that reveals all of Sacred Scripture in the readings for the Church’s liturgy spread over a three-year cycle. I discovered only while writing this post for the occasion of my 39th anniversary of priesthood ordination that the First Reading at Mass on that day — Saturday, June 5, 2021 — is the story of the Archangel Raphael sent by God to restore life and sight to Tobit and bring deliverance and healing to two souls — Tobias and Sarah — whose lives and sufferings converged upon Tobit’s at that point in time.

As I mark thirty nine years as a priest in extraordinary circumstances, the weight of imprisonment does not leave me broken. But the irony of grace leaves me hopeful — even now.

Thank you for being a part of my life as a priest. Thank you for being here with me at this turning of the tide.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: We have a most important message for readers. Please visit our “Special Events” page.

+ + +

You may also like these related posts:

From Down Under, the Exoneration of Cardinal George Pell

Priesthood, The Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times

Tom Clancy, Jack Ryan, and The Hunt for Red October

Novelist Tom Clancy, master of the techno-thriller, died on October 1st. His debut Cold War novel, The Hunt for Red October, was an American literary landmark

Novelist Tom Clancy, master of the techno-thriller, died on October 1st. His debut Cold War novel, The Hunt for Red October, was an American literary landmark.

In 2011 at Beyond These Stone Walls, I wrote a post for All Souls Day entitled “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.” Some readers who have lost loved ones very dear to them found solace in its depiction of death as a continuation of all that binds human hearts and souls together in life. Like all of you, I have lost people whose departure left a great void in my life.

It’s rare that such a void is left by someone I knew only through books, but news of the death of writer, Tom Clancy at age 66 on October 1st left such a void. I cannot let All Souls Day pass without recalling the nearly three decades I’ve spent in the company of Tom Clancy.

I’ll never forget the day we “met.” It was Christmas Eve, 1984. Due to a sudden illness, I stood in for another priest at a 4:00 PM Christmas Eve Mass at Saint Bernard Parish in Keene, New Hampshire. I had no homily prepared, but the noise of a church filled with excited children and frazzled parents conspired against one anyway. So I decided in my impromptu homily to at least try to get a few points of order across.

Standing in the body of the church with a microphone in hand I began with a question: “Who can tell me why children should always be quiet and still during the homily at Mass?” One hand shot up in the front, so I held the microphone out to a little girl in the first pew. Proudly standing up, she put her finger to her lips and whispered loudly into the mic, “BECAUSE PEOPLE ARE SLEEPIN’!”

Of course, it brought the house down and earned that little girl — who today would be about 38 years old — a rousing round of applause from the parishioners of Saint Bernard’s. It lessened the tension a bit from what had been a tough year for me in that parish.

But that’s not really the moment I’ll never forget. After that Mass, a teenager from the parish walked into the Sacristy to hand me a hastily wrapped gift. In fact, it looked as though he wrapped it during the homily! “We’re not ALL sleeping,” he said about the little girl’s remark. I laughed, and when it was clear that he wasn’t leaving in any hurry, I asked whether he wanted me to open his gift. He did. I joked about needing bolt cutters to get through all the tape. It was a book. It was Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October. “Oh, wow!” I said. “How did you know I’ve been wanting to read this?”

It was a lie. I admit it. But it was a white lie. It was the sort of lie one tells to spare the feelings of someone who gives you a book you’ve never heard of and had no plan to read. I remember hearing about a circa 1980 interview of Barbara Walters with “Miss Lillian,” a Grand Dame of the U.S. South and the mother of then President Jimmy Carter. Miss Lillian — to the chagrin of presidential handlers — declared that her son, the President, “has nevah told a lie.”

“Never?!” prodded Barbara Walters. “Well, perhaps just a white lie,” Miss Lillian hastily added. “Can you give us an example of a white lie?” asked Barbara Walters. After a thoughtful pause, Miss Lillian looked her in the eye and reportedly said in her pronounced Southern drawl, “Do you remembah backstage when Ah said you look really naace in thaat dress?” Barbara was speechless! First time ever!

Mine was that sort of lie. The young giver of that gift would be about 43 years old today, and if he is reading this I want to apologize for my white lie. Then I also want to tell him that his gift changed the course of my life with books. I had read somewhere that First Lady Nancy Reagan also gave that book as a gift that Christmas. True to his penchant for adding new words to the modern American English lexicon, President Ronald Reagan declared The Hunt for Red October to be “unputdownable!”

So after a few weeks collecting dust on my office bookshelf I took The Hunt for Red October down from the shelf and opened its pages late one winter night.

“Who the Hell Cleared This?”

After busy days I have a habit of reading late at night, a habit that began almost 30 years ago with this gift of Tom Clancy’s first novel. Parishioners commented that they drove down Keene’s Main Street at night to see the lights on in my office, and “poor Father burning midnight oil at his desk.” I was doing nothing of the sort. I was submersed in The Hunt for Red October, at sea in an astonishing story of courage and patriotism.

In the early 1980s, the Cold War was freezing over again. The race to develop a “Star Wars” defense against nuclear Armageddon dominated the news. President Ronald Reagan had thrown down the gauntlet, calling the Soviet Union an “Evil Empire.” Pope John Paul II was working diligently to dismantle the Soviet machine in Poland. The Soviet KGB was suspected of being behind an almost deadly attempt to assassinate the pope. It was an event that later formed yet another powerful and stunning — and ultimately true — Tom Clancy/Jack Ryan thriller, Red Rabbit.

In the midst of this glacial stand-off between superpowers that peaked in 1984, Tom Clancy published The Hunt for Red October. Its plot gripped me from page one. The Soviets launched the maiden voyage of their newest, coolest Cold War weapon, a massive, silent, and virtually undetectable ballistic nuclear missile submarine called “Red October.” Before embarking, the Red October’s Captain, the secretly renegade Marko Ramius, mailed a letter to his Kremlin superiors indicating his intent to defect and hand over the prized sub’s technology and nuclear arsenal to the government of the United States.

By the time the Red October departed the Barents Sea for the North Atlantic, the entire Soviet fleet had been deployed to hunt her down and destroy her. American military intelligence knew only that the Soviets had launched a massive Naval offensive. An alarmed U.S. Naval fleet deployed to meet them in the North Atlantic, bringing Cold War paranoia to the brink of World War III and nuclear annihilation.

Having few options in the book, the Soviets fabricated to U.S. intelligence a story that they were attempting to intercept a madman, a rogue captain intent on launching a nuclear strike against America. Captain Marko Ramius and the Red October were thus hunted across the Atlantic by the combined Naval forces of the world’s two great superpowers operating in tandem, and in panic mode, but for different reasons.

Then the world met Jack Ryan, a somewhat geeky, self-effacing Irish Catholic C.I.A. analyst and historian. Ryan, with an investigator’s eye for detail, had studied Soviet Naval policies and what files could be obtained on its personnel. Jack Ryan alone concluded that Captain Marko Ramius was not heading for the U.S. to launch nuclear missiles, but to defect. Ryan had to devise a plan to thwart his own country’s Navy, and simultaneously that of the Soviet Union, to bring the defector and his massive submarine into safe harbor undetected.

In the telling of this tale, Tom Clancy nearly got himself into a world of trouble. His understanding of U.S. Navy submarine tactics and weapons technology was so intricately detailed that he was suspected of dabbling in leaked and highly classified documents. When Navy Secretary, John Lehman read the book, he famously shouted, “WHO THE HELL CLEARED THIS?”

The truth is that Tom Clancy was an insurance salesman whose handicap — his acute nearsightedness — kept him out of the Navy. He wrote The Hunt for Red October on an IBM typewriter with notes he collected from his research in the public records of military technology and history available in public libraries and published manuals. His previous writing included only a brief article or two in technical publications.

The Hunt for Red October was so accurately detailed that its publishing rights were purchased by the Naval Institute Press for $5,000. Clancy hoped that it might sell enough copies to cover what he was paid for it. It became the Naval Institute’s first and only published novel, and then it became a phenomenal best seller — thanks in part to President Reagan’s declaration that it was “unputdownable.” And it was! It was also — at 387 pages — the smallest of 23 novels yet to come in a series about Clancy’s hero — and alter ego — Jack Ryan.

The World through the Eyes of Jack Ryan

After devouring The Hunt for Red October in 1984, for the next 25 years — and nearly 17,000 pages of a dozen techno-thrillers — I was privileged to see the world and its political history through the eyes of Tom Clancy’s great protagonist, Jack Ryan.

From that submarine hunt through the North Atlantic, Tom Clancy took us to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in The Cardinal of the Kremlin, the Irish Republican Army’s terrorist branches in Patriot Games, the drug cartels of Colombia in Clear and Present Danger, and the threat of domestic terrorism in The Sum of All Fears. This list goes on for another seven titles in the Jack Ryan series alone as the length of Tom Clancy’s stories grew book by book to the 1,028-page tome, The Bear and the Dragon, all published by Putnam. I wrote of Tom Clancy again, and of his gift for analyzing and predicting world events, in one of the most important posts on BTSW, “Hitler’s Pope, Nazi Crimes, and The New York Times.”

At the time of Tom Clancy’s death at age 66 on October 1st, he had amassed a literary franchise with 100 million books in print, seven titles that rose to number one on best seller lists, $787 million in box office revenues for film adaptations, and five films featuring his main character, Jack Ryan, successively portrayed by Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck, and Chris Pine (the latter, and his final book, due out in December 2013).

I once made the chauvinistic mistake of calling Tom Clancy’s novels “guy books.” Mea culpa! It isn’t so, and I was divested of that view by several women I know who love his books. Writing in USA Today (“Tom Clancy wrote America well,” October 9) Laura Kenna wrote of Tom Clancy’s sure-footed patriotism as America stood firm against the multitude of clear and present dangers:

“We will miss Tom Clancy, his page-turning prose and the obsessive attention to detail that brought the texture of reality to his books. We have already been missing the political universe from which Clancy came and to which his books promised to transport us, a place never simple, but still certain, where clear convictions made flawed Americans into heroes.”

Tom Clancy was himself a flawed American hero whose nearsighted handicap was in stark contrast to the clarity and certainty of vision that he gave to Jack Ryan, and to America. I think, today, Clancy might write of a new Cold War, not the one about nuclear warheads pointing at America, but the one about Americans pointing at each other. He might today write of a nation grown heavy and weary with debt and entitlement.

As Tom Clancy slipped from this world on October 1, 2013, his country submerged itself into a sea of darker, murkier politics, those of a nation still naively singing the Blues while the Red October slips quietly away.