“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The True Story of Thanksgiving: Squanto, the Pilgrims, and the Pope

We and the Mayflower Pilgrims owe thanks to the Pope and some Catholic priests for the Thanksgiving of 1621 with Squanto and the Plymouth Colony.

We and the Mayflower Pilgrims owe thanks to the Pope and some Catholic priests for the Thanksgiving of 1621 with Squanto and the Plymouth Colony.

Thanksgiving by Fr Gordon MacRae

Growing up within sight of Boston, Massachusetts meant lots of grade school field trips to the earliest landmarks of America. We looked forward to those excursions because they meant a day out of school. The only downside was the inevitable essay. Back then, I had no love for either history or essays. Go figure!

Some field trips are vividly remembered even six decades later. A visit to the deck of “Old Ironsides,” the U.S.S. Constitution in Boston Harbor, stands out as the most exciting. Visits to the sites of the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party, and Paul Revere’s famous ride also stand out as great adventures in hands-on U.S. history — the essays notwithstanding.

Then there was the trip to Plymouth Rock (YAWN!), the most underwhelming national monument in America. Everyone of us emerged from the bus to file past Plymouth Rock while poor Mr. Dawson had to listen to an endless cascade of “That’s IT?!”

“Dedham granodiorite.” That’s the scientific name of the rock where the Mayflower Pilgrims were left to settle in the New World in what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts. Plymouth Rock was noted and described in the Pilgrims’ journals, but it fell into obscurity for a century until the town of Plymouth decided to build a wharf in 1741. That’s when 94-year-old church elder Thomas Faunce set out to identify Plymouth Rock and mark the site. Thirty-four years later, the town moved the rock to a more prominent location, accidentally breaking it in half in the process. Only the top half made its way to the town’s new site.

Then shopkeepers began chiseling away at it, selling chunks to tourists for $1.50 each. Over the ensuing years, Plymouth Rock was moved again and again, split in half a second time, cemented back together, then what was left of it ended up surrounded by a concrete portico to become the nation’s first national landmark.

You Can Say That Again!

Every year since 1961 on the day before Thanksgiving, The Wall Street Journal publishes the same two lead editorials by Vermont C. Royster. They are considered classics. “The Desolate Wilderness” describes the purpose and plight of the Puritan founders of New England who left such a deeply engraved mark, for better or worse, on the spirit of this nation. “And the Fair Land” lays out the free market foundation upon which American enterprise was built. These editorials are now a Thanksgiving tradition, and if the WSJ can get away with annual repetition, so can I.

This year I’m revisiting the story of Squanto and the Pilgrims, with a few additions and updates, and posting it before Thanksgiving in the hope it might be Tweeted, pinged, e-mailed, and otherwise shared.

The lack of awe inspired by Plymouth Rock is in inverse proportion to the story of how the Pilgrims came to stand upon it. Every grade school student knows the tale of the Mayflower. In 1620, its pilgrim sojourners fled religious persecution from the established Church of England. They embarked on a long and treacherous voyage across the Atlantic in the leaky, top-heavy Mayflower. Landing at Plymouth, Massachusetts, the Pilgrims befriended the native occupants, endured many hardships, then, after a successful first harvest in the New World, celebrated a Thanksgiving feast with their Native American friends in the autumn of 1621.

That story is true, as far as it goes, but the story your grade school history book omitted is downright fascinating, and every Catholic should know of it. Before boarding the Mayflower, the Pilgrims were called “Separatists.” The religious “persecution” they came here to flee consisted mostly of their determination to purge the remnants of Catholicism from the established Church of England.

Author, Philip Lawler summarized their agenda in his book, The Faithful Departed: The Collapse of Boston’s Catholic Culture (Encounter Books, 2008):

“[T]he Puritans were campaigning against the lingering traces of Catholicism. Decades of brutal persecution — first under Henry VIII, then under Elizabeth I — had eliminated the Roman Church from English public life in the sixteenth century; the country’s few remaining faithful Catholics had been driven underground. For the Puritans, that was not enough . . . They were determined to erase any vestigial belief in the sacraments, any deference to an ecclesiastical hierarchy.”

— Philip Lawler in The Faithful Departed

The Pilgrims came here to establish a New World theocracy, a religiously oriented society that would reflect their religious fervor which was also anti-Catholic.

Puritanism deeply affected the American national character, but I wonder if the Pilgrims would even recognize the American religious landscape of today. It is far from what they envisioned.

The Puritan Pilgrims were not always considered the survivors of religious persecution American history made them out to be. Writer, H.L. Mencken described Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” And G.K. Chesterton once famously remarked:

“In America, they have a feast to celebrate the arrival of the Pilgrims. Here in England, we should have a feast to celebrate their departure.”

— G.K. Chesterton

Pilgrim’s Progress

When the Pilgrims stepped off the Mayflower on December 11, 1620, they were not at all prepared for life in the New World. They were originally destined to colonize what is now Virginia, but the Mayflower veered badly off course. They also considered settling at the mouth of the Hudson River in modern day New York, but Dutch traders conspired to prevent it.

Before leaving England on September 16, 1620, the Pilgrims used their meager resources to purchase a second ship to sail along with the Mayflower and remain with them in the New World. That vessel was called the Speedwell. It was anything but well, however, nor was it speedy. Just 200 miles off the English coast, the Speedwell was sinking. Those aboard had to transfer to the crowded Mayflower while the Speedwell returned to England. There was evidence that the Speedwell was intentionally rigged to fail, leaving the colonists with no vessel with which to explore once the Mayflower departed.

The voyage across the Atlantic was delayed for months, finally landing the Pilgrims in New England at the start of winter. There were 102 aboard the Mayflower when it left England, but by the end of their first winter in the New World, only half that number were still alive. Unable to plant in the dead of winter, their first encounter with the indigenous people of coastal Massachusetts — known to those who lived there as “The Dawn Land” — came when the near starving Pilgrims stole ten bushels of maize from an Indian storage site on Cape Cod. It was not a good beginning.

Massasoit, the “sachem” (leader) of the once powerful Wampanoag tribe, was not at all enamored of the visitors, and the fact that they seemed intent on staying disturbed him greatly. The Pilgrims had no way to know that prior European visitors to those shores left diseases to which the people of The Dawn Land had no natural resistance. By the time the Pilgrims arrived, 95% of the indigenous population of New England, including the Wampanoag, had been decimated.

Still, Massasoit could have easily overtaken and destroyed the invaders, who were barely surviving, but they had something he wanted. Massasoit feared that his tribe’s weakened state might spark an invasion from rivals to the south, and he noted that the Pilgrims had a few cannons and guns that could help even the odds.

The Pilgrims Meet “The Wrath of God”

So instead of attacking the Pilgrims, Massasoit sent an emissary in the person of Tisquantum, known to history as Squanto. He was actually a captive of Massasoit and arrived just weeks before the Pilgrims. Tisquantum was likely not his original name. In the language of the people of The Dawn Land, Tisquantum meant the equivalent of “the wrath of God.” It may have been a name given to him, and, as you’ll see below, perhaps for good reason.

Squanto was to become the primary force behind the Pilgrims’ unlikely survival in the New World. On March 22, 1621, the vernal equinox, Squanto walked out of the forest into the middle of the Pilgrims’ ramshackle base at Plymouth, a settlement known to Squanto as Patuxet. That place was once his home. To the Pilgrims’ amazement, Squanto spoke nearly perfect English, and arrived prepared to remain with them and guide them through everything from fishing to agriculture to negotiations with the nervous and well-armed Massasoit and the Wampanoag.

As historian Charles C. Mann wrote in “Native Intelligence,” (Smithsonian, December 2005), “Tisquantum was critical to the colony’s survival.” Squanto taught them to plant the native corn they had stolen instead of just eating it, and he negotiated a fair trade for the theft of the corn. The Pilgrims’ own supplies of grain and barley all failed in the New World soil while the native corn gave them a life-saving crop. Squanto taught them how to fish, and how to fertilize the soil with the remains of the fish they caught. Most importantly, Squanto served as an advocate and interpreter for the Pilgrims with Massasoit, averting almost certain annihilation of the weakened and distrusted foreigners.

A Catholic Rescue

For their part, the Pilgrims interpreted Squanto’s presence and intervention as acts of Divine Providence. They had no idea just how much Providence was involved. It is the story of Squanto — of how he came to be in that place at that very time, and of how he came to speak fluent English — that is the most fascinating story behind the first Thanksgiving.

In 1614, six years before the arrival of the Mayflower, Captain John Smith — the same man rescued by Pocahontas in another famous tale — led two British vessels to the coast of Maine to barter for fish and furs. When Smith departed from the Maine shore, he left a lieutenant, Thomas Hunt, in command to load his ship with dried fish.

Without consultation, Thomas Hunt sailed his ship south to what is now called Cape Cod Bay. Anchored off the coast of Patuxet (now Plymouth) in 1614, Hunt and his men invited two dozen curious native villagers aboard the ship. One of them was Squanto. Once aboard, the Indians — as the Europeans came to call them — were forced into irons in the ship’s hold. Kidnapped from their homes and families, they were taken on a six-week journey across the Atlantic. Not all the captives survived the voyage. Those who did survive, Squanto among them, were brought to Malaga off the coast of Spain to be sold as slaves.

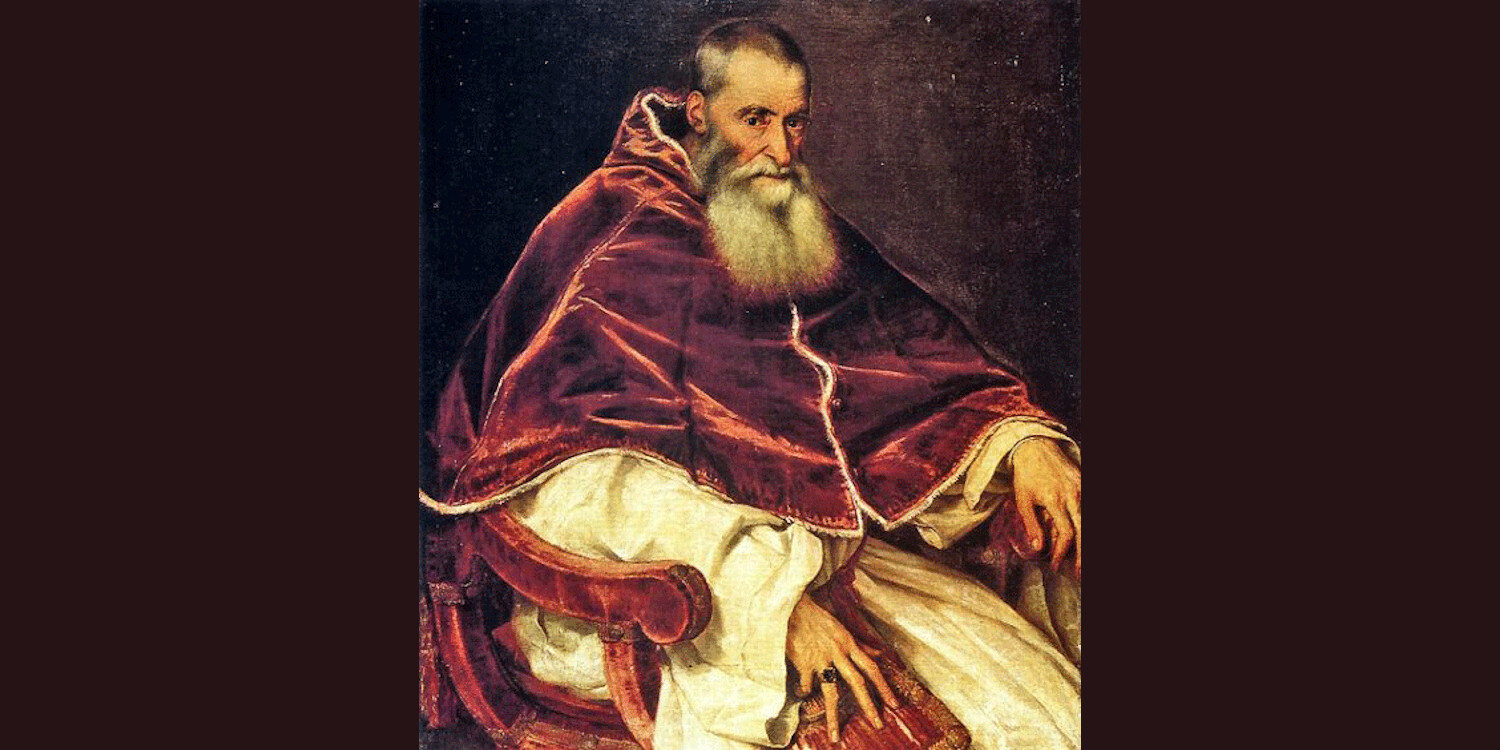

Fortunately for Squanto, and later for our Pilgrims, Spain was a Catholic country. Seventy-seven years earlier, envisioning injustices visited upon the indigenous peoples of the New World, Pope Paul III issued “Sublimus Dei,” a papal bull forbidding Catholic governments from enslaving or mistreating Indians from the Americas. The Pope declared that Indians are “true men” who could not lawfully be deprived of liberty. “Sublimis Dei” instructed that European intervention into the lives of Indians had to be motivated by benefit to the Indians themselves. It would take America another 300 years to catch up with the Catholic Church and abolish slavery.

As a result of the papal decree, the Catholic Church in Spain was opposed to the mistreatment of Indians, and opposed to bringing them to Europe against their will. Of course, the Catholic ideal did not always prevent slave trade on the black market. At Malaga, Thomas Hunt managed to sell most of his captives, and was about to sell Squanto when two Spanish Jesuit priests intervened. The Spanish-speaking priests seized Squanto who somehow convinced them to send him home. Not knowing where “home” was, the priests arranged for Squanto’s passage as a free man on a ship bound for London. It is likely that the Jesuits even baptized Squanto as a Catholic. It would have been a way to assure his status as a free man.

Squanto’s world tour was underway. In late 1614, having no idea where he was, Squanto walked into the London office of John Slaney, manager of the Bristol Company, a shipping and merchant venture that had been given rights to the Isle of Newfoundland by England’s King James I in 1610. Squanto spent the next three years stranded in London before being placed on a ship bound for St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1617. By now fully immersed in the language and ways of the English, Squanto spent another two years stranded in Newfoundland — 1,000 miles of sea and rocky coast still separating him from his native Patuxet.

Late in 1619, Squanto befriended Thomas Dermer, a British Merchant in Newfoundland who agreed to sail Squanto home, though neither knew where home was. They knew it was south, so south they sailed. Squanto eventually recognized a Patuxet landmark — maybe even what we came to call Plymouth Rock.

With Thomas Dermer’s ship anchored off Patuxet, Squanto stepped onto the shores of home after a nearly six year absence. But the people of The Dawn Land — Squanto’s people — were no more. Squanto was devastated to learn that disease had ravaged his home in his absence, and not a single Patuxet native had survived. Squanto was alone.

Squanto knew he could not remain there. He convinced Thomas Dermer to accompany him inland in search of anyone among his people who might have survived. There was no one. It wasn’t long before both men were taken captive by Massasoit, sachem of what had been a confederation of 20,000 native Massachuset and Wampanoag tribal peoples. By the time Squanto and Thomas Dermer stood captive before Massasoit, however, all but 1,000 of them were dead from diseases carried to the New World aboard European vessels.

Just weeks later, it was to this setting that the Mayflower’s naive and ill-prepared Pilgrims arrived to face the winter of 1620 in the New World. Squanto, now alone — his life ravaged and his home and people destroyed — convinced Massasoit to send him to the Pilgrims as a negotiator and interpreter instead of attacking them. Squanto put his wrath aside, and became a bridge linking two disparate worlds.

Without Squanto — and, indirectly at least, the Pope and some Jesuit priests — the fate of the Puritan Pilgrims would have been vastly different, and Thanksgiving would likely have never taken place. Squanto was, as Governor William Bradford of Plymouth Plantation wrote of him,

“A spetiall instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectations.”

On that point, both Puritans and Catholics might agree. At your Thanksgiving table this year, say a prayer of thanks for Tisquantum — Squanto. Our national ancestors were once pilgrims and strangers in a strange land, and that land’s most disenfranchised citizen assured their survival.

+ + +

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The Last Full Measure of Devotion: Civil Rights and the Right to Life

Racial justice and a dubious idea of critical race theory are now center stage in our culture, but they give no voice to the most urgent Civil Rights issue of all.

Racial justice and a dubious idea of critical race theory are now center stage in our culture, but they give no voice to the most urgent Civil Rights issue of all.

For the entire second term in the presidency of Barack Obama, Ohio Republican congressman John Boehner was Speaker of the House of Representatives. He left that office in 2015. A devout Catholic, he had been honored by the University of Notre Dame with the Laetare Medal, a distinction awarded to Catholics in public life who witness to their faith in extraordinary ways. During Speaker Boehner’s first address to the House of Representatives in 2011, he said that “America is more than a country. It’s an idea.” Like any great idea, it did not begin in its current form. The idea of America evolved with fits and starts in response to both prophets and protests — and wars, and great losses, and immense sacrifices. From my perspective, in the decade from 1963 to 1973 the very idea of America gave birth to a Civil Rights movement that was hard fought and continues to be. Milestones were reached, but the Civil Rights movement never ended. It now just takes another form.

Civil Rights as an idea is not yet a done deal. Just as the idea formed and took shape for some in America, it failed an entire class of others. Just as the idea of Civil Rights embraced our fellow Americans living lives marked by racial divisions and distinctions, it failed millions of others not yet living outside the womb.

In the decade of the 1970s, it sometimes felt like I would be in school forever. After four years studying psychology and philosophy at Saint Anselm College, a Benedictine school just outside Manchester, NH, I commenced another four years at Saint Mary Seminary and University in Baltimore, Maryland from where I was awarded a Master of Divinity and a Pontifical degree in Sacred Theology. Saint Mary’s is the oldest Catholic seminary in the United States and, at that time at least, was the most academically demanding.

Like many seminarians then, I was chronically poor. During the rationing and long gas lines of the late 1970s, I paid $900 for a clunker of a 1969 Chevy Malibu. It had a V-8 engine that could pass everything but gas stations, and when I bought it, it burned almost as much oil as gasoline. A friend and I spent all our spare time in the summer of 1978 rebuilding its engine before I drove it off to Baltimore to begin the great adventure of faith seeking understanding. I was proud of the fact that we got the Malibu’s gas mileage up to a point where I could sit in the long gas lines with a clear conscience, though I don’t think General Motors would have still recognized its engine. I loved that car, not the least for where it took me.

Roaring around Baltimore from 1978 to 1982, I quickly learned that the great city was second only to my native Boston for the lure and lore of its history. Outside the seminary, there was a whole other field of education within 100 miles of Baltimore in any direction. So Saturdays in the seminary were devoted to field trips to the birth and growth of America; to the places where the idea first took shape. That’s when visiting history became my hobby, and an important part of my education. Much more than my loss of freedom, now, I mourn the passing of the world beyond these stone walls.

Upon the Field of Battle

One place stands out strikingly against the background of monuments and memories I visited and studied. I had some friends among the seminarians at Mount Saint Mary Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland, a two+ hour drive from Baltimore. On several Saturdays, my speedy Malibu drove north to pick up my friends and head for Gettysburg, just a few miles from Emmitsburg straddling the Maryland and Pennsylvania state line.

It’s hard to describe what I felt the first time I stood surveying the very heart of America’s most terrible war. The Battle of Gettysburg was fought there over the first four days of July in 1863. President Abraham Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address was delivered on that field on November 19, 1863, just three months after the horrific four-day battle that took the lives of over 80,000 Americans.

For some reason, standing on that field of battle for the first time in 1979, I thought of John F. Kennedy and his signature cause, the Civil Rights movement which was in turn taken up by President Lyndon Baines Johnson after Kennedy’s untimely death in 1963. It came as a shock to me to realize that the defining battle of the American Civil War — that I once thought to be ancient history — was fought and then immortalized in Lincoln’s great speech just l00 years before the assassination of John F. Kennedy. It was exactly 100 years, barely three generations in the lives of men. The Battle of Gettysburg, and all that led up to it, took place in the lifetime of my grandfather’s grandfather.

Suddenly, with that revelation, I felt linked to all that came before. Michael Shaara’s Pulitzer Prize winning 1974 historical novel, The Killer Angels relived this most decisive battle of the American Civil War, and my first visit came just after this great work of historical storytelling.

It felt strange standing for the first time upon Cemetery Hill where the Civil War pivoted toward victory for the North. But there was really no victory. It was America against itself, and the powerful imprint of death and sacrifice was still upon that battlefield as I stood there 116 years later. It was both eerie and inspiring. My friends went off to tour the museum and stare at row upon row of cannonballs and muskets, but I couldn’t leave that field. I realized standing there for the first time just what an idea can cost, and what hardship and sacrifice it can demand from those who serve it.

The Right to Life and the Cost of Liberty

By the time the Civil War was over, it demanded of America more lives of its citizens than World War I and World War II combined. Some 500,000 lost their lives fighting this nation’s war against itself. I didn’t understand then just how this happened, but standing on that Gettysburg field, I resolved to one day understand. Men and women can sacrifice their lives for an idea, or an ideal, or a principle that is far greater than themselves. They can sacrifice freedom, even, to stand firm on a ground made solid by conscience.

Many historians and legal scholars draw a direct line between the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 and a single case decided before the U.S. Supreme Court four years earlier in 1857. As a causal connection, the decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford enraged conscience-driven abolitionists and encouraged slave owners. It broadened the political and ideological abyss between the North and the South, and it led directly to a war of nothing less than the demands of conscience versus the realities of economic necessity and convenience.

Dred Scott was a fugitive slave. In 1848 at the age of 62, having spent decades in secret learning to read and write, he brought suit to claim his freedom on the ground that he resided in a free territory established by the 1820 Missouri Compromise. This is a piece of American history that must not be overlooked or forgotten, though many would prefer not to know. Dred Scott was purchased and lived his life as a slave, but was then taken by his “master”, an Army surgeon, to a free territory rendered free by the Missouri Compromise.

In Dred Scott v. Sanford, Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney wrote for the majority that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional and violated the Fifth Amendment because it deprived Southerners of a right to bring their private property — i.e., slaves — wherever they wanted. The decision further ruled that Congress did not have the authority to establish free territory, and in its most alarming language, Justice Taney’s decision established that black men are not citizens of the United States and had “no rights any white man is bound to respect.”

Reflecting upon this now, five generations later, is made all the more painful by the recognition that Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney was a Catholic, though one who surely put the realities of national economics above the tenets of faith or conscience. As I wrote in “The True Story of Thanksgiving,” the Catholic Church had three centuries earlier established slavery as a moral evil, and declared it unacceptable in any Catholic country. It would take another 250 years from the founding of America for this nation to put economic interest aside and catch up with the conscience of the Catholic Church.

Justice Taney’s decision caused some in his day to conclude that there is a higher moral law than the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution at any given time in history. There is a higher moral law, and it led the nation on a direct path from Dred Scott to Civil War. The war came as a result of the conscience of individuals gradually forming a consensus about slavery, racial justice and the rights of man.

Rev. Martin Luther King and Father John Crowley

One hundred years after that war was fought, its ripples continued throughout this nation. In 1968, Rev. Martin Luther King was assassinated for his unwavering and prophetic public witness in a story that we all know only too well. My friend, the late Father Richard John Neuhaus (who contributed to our “About” page) wrote of the radical grace exemplified by Martin Luther King in American Babylon: Notes of a Christian Exile. He wrote of Dr. King’s notion of “The Beloved Community” and described his movement as a new order . . .

“. . . sought by all who know love’s grief in refusing to settle for a community of less than truth and justice uncompromised.”

Think for a moment, please, about that statement. There are not many of us who escape love’s grief — unless we become so shallow as to so steel ourselves against grief that we can ignore it. What a tragedy! Those of us who know love’s grief and refuse to settle for a community — a nation, a Church — of less than truth and justice uncompromised are in for some prophetic suffering.

Three years before Martin Luther King was assassinated, Father John Crowley, a heroic Catholic priest, was nearly driven from Selma, Alabama when he took out a full-page ad in the Selma Times-Journal on February 7, 1965.

His ad contained a brilliant essay entitled “The Path to Peace in Selma.” It urged the white community to speak out against racial segregation and discrimination not for the good of the black man and woman, but for the good of ALL men and women. Like the famous Lutheran Pastor, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, executed on the personal orders of Adolf Hitler on April 9, 1945, Father John Crowley called upon fellow priests and other Catholics to put aside their fears of loss and stand by the truth uncompromised. I share a date of birth with the date of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s death, and I share my June 5th date of priesthood ordination with Father John Crowley. These very special men compel me to stand always by the truth uncompromised, and not to fear its cost.

Stand against the Culture of Death

Martin Luther King lost his life just five years before another divisive Supreme Court decision with grave implications for Civil Rights. There are some, and they are many, who see in the 1857 decision in Dred Scott the roots of the 1973’s Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade. Justice Antonin Scalia and Justice Anthony Kennedy have both cited this connection. In 1973, after the Supreme Court handed down its divided decision in Roe v. Wade, the State of Texas joined other states in filing a petition for a rehearing before the full Court. The Texas dissent declared that the decision in Roe that an unborn child was not a human being with rights to be protected was not at all unlike the decision in Dred Scott that virtually no just person in this nation would ever stand by today.

And just as Dred Scott inspired dissidents of conscience to hear the Commandments of a Higher Authority, Roe v. Wade has inspired similar heroism, most of it barely noticed in the mainstream media, or, worse, taunted. Have you noticed that much of the loudest ridicule of the Catholic Church in America comes on the heels of legislation that chips away at the right to life and human dignity? Many a media barrage against the Catholic Church has been for the purpose of silencing its pro-life voice in the public square.

Life Site News has carried the stories of two Canadian women whose sacrifices on behalf of civil rights for the unborn had landed them in prison. Linda Gibbons, a grandmother and prisoner of conscience, spent seven years in an Ontario prison because she refused to comply with a court order demanding that she cease and desist from standing on the sidewalk near an Ontario clinic to present alternatives to abortion. In eerie echoes of the Dred Scott decision, the clinic staff and the Ontario court charged her with interfering with fair commerce by suggesting to clients another way. Linda Gibbons first went to prison at the same time I did, in September 1994.

Mary Wagner took leave from a French convent to “witness to life” as Life Site News has called her sacrifice. In Holy Week, 2010, Mary was arrested by Vancouver police and remained in jail for months for refusing to obey court orders to cease talking to abortion clinic clients about Project Rachel.

And you may have heard of the late Norma McCorvey. She’s better known as “Jane Roe,” the plaintiff in the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision. Norma became a Catholic in 1998 and also became a dedicated pro-life activist. She was author of the 1998 book, Won by Love. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a petition by Norma McCorvey to reverse Roe v. Wade. In May 2009, she was among the Catholic pro-life witnesses arrested at the University of Notre Dame during President Obama’s Commencement address.

We can deduce where Martin Luther King would stand on the pressing civil rights issues of this day. There is some annual controversy that his niece, Dr. Alveda King, endeavors to clear up. She staunchly defends Rev. King against claims that he would be a pro-choice or pro-abortion supporter today. She insists that his civil rights agenda would today include a defense of life. It’s no irony that the week that begins in honor of his martyrdom for civil rights ends with the National March for Life in Washington, DC.

Beginning in the fall of 2004, 40 Days for Life has held prayer vigils at 238 locations in the U.S., Canada, England, and Australia. The US Catholic Bishops would do well to heed the courageous voices of those who have sacrificed much for the pro-life cause while the bishops debate the sanctity of the Eucharist and the demeanor necessary to receive the Body of Christ. The great Lutheran pastor, Deitrich Bonhoeffer, went to prison for writing to his fellow Lutherans that they cannot both profess their belief in Christ and support the Third Reich and its culture of death.

Conceived in Liberty

On the Saturday after my first visit to Gettysburg in 1979, I drove an hour south from Baltimore to Washington, DC. I went first to the Lincoln Memorial where the famous Gettysburg Address is etched into the stone behind the immense man’s monumental presence. The great speech immortalized the struggle for civil rights as an ongoing struggle that must never be set aside if the idea of America is to survive.

As I read it, I thought of that awful battlefield where I stood 116 years later, and also of the civil rights battlefields of today where millions are denied the right to life, and the millions more who sacrifice to witness for them. Lincoln’s memorable words apply no less to them.

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battle field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger-sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from those honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: As readers know, we have restored a few older posts in the last three weeks while I have been unable to write. This post was first written in 2011. It has been substantially updated and revised so it is actually a new post. Among the several pro-life posts I have written, many readers thought this one to stand out.

The Supreme Court has announced that it will review limits on abortion which in turn could lead to a review of Roe v Wade. President Biden just announced his new commission to study packing the Court. There is too much at stake to stay on the sidelines. Please share this post.

You might also be interested in this related post: