“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

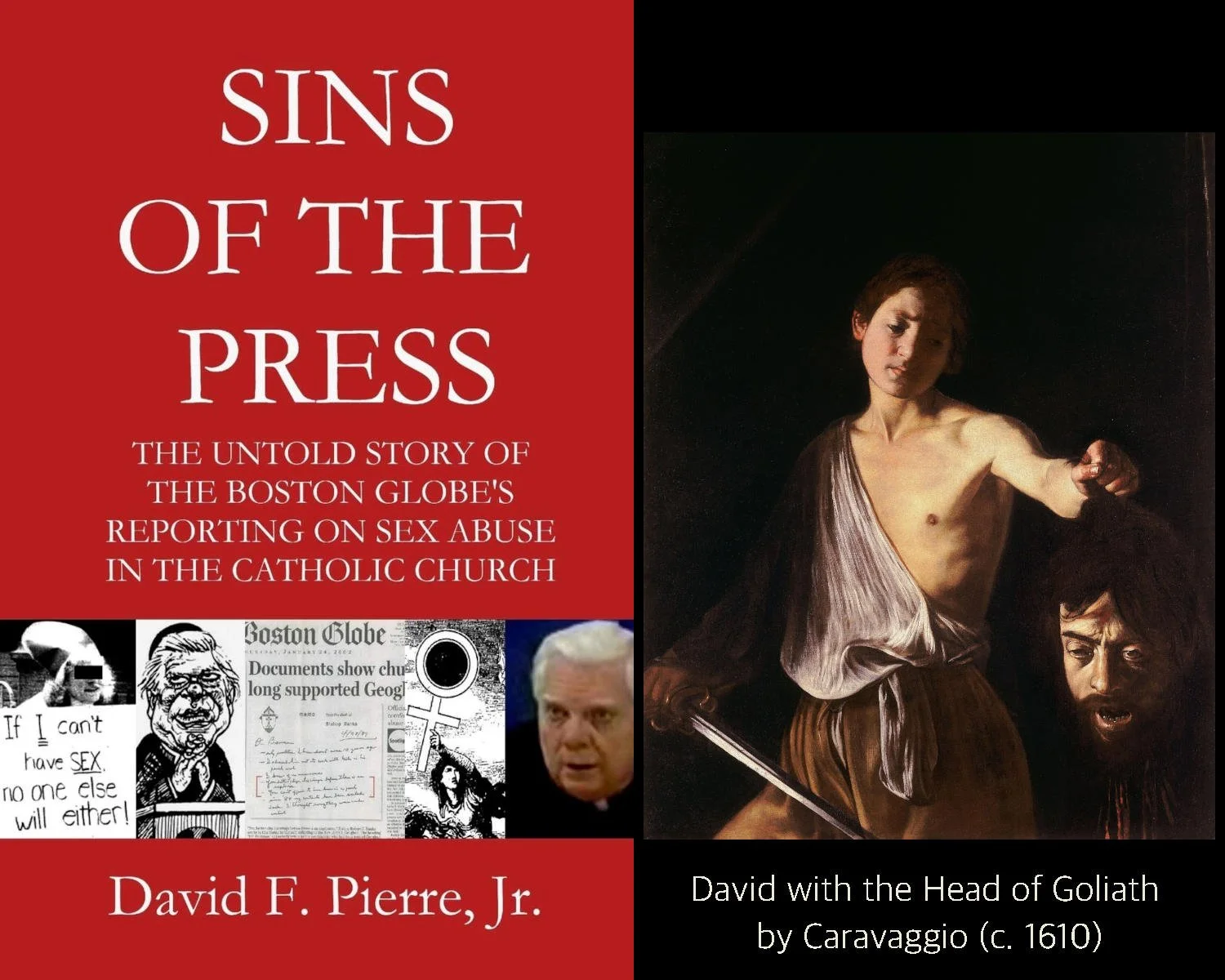

Sins of the Press: David and the Truth About Goliath

In his book, Sins of the Press, Catholic writer and media equalizer David F Pierre Jr, takes aim at a news Goliath: The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer-endorsed Prejudice.

In his book, Sins of the Press, Catholic writer and media equalizer David F Pierre Jr, takes aim at a news Goliath: The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer-endorsed Prejudice.

October 15, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

Do you remember Robert McCall? He was The Equalizer, a retired espionage operative in a popular 1980s TV series. It was never clear whether he was CIA or MI6, but each week he placed his formidable skills in the service of some underdog up against powerful oppressors. With British actor Edward Woodward in the role of Robert McCall, The Equalizer managed to even the odds against a perfect storm of tyranny. He appeared rather benign, and at times he seemed a bit in over his head, but he was patient and bided his time. When he struck, the powerful and powerfully corrupt were unmasked and undone.

In a world of media atrocities, David F. Pierre, Jr. aims to be an equalizer. With the patience of Job, he waited a dozen years before loading his small stone of an expository book into a sling to take aim at a media Goliath, in this case The Boston Globe and its 2003 Pulitzer Prize for — don’t miss the irony in this — “Public Service.” Here’s how the Pulitzer Committee described its 2003 award to The Boston Globe…

“… for its courageous, comprehensive coverage of sexual abuse by priests, an effort that pierced secrecy, stirred local, national, and international reaction, and produced changes in the Roman Catholic Church.”

I found that description by the 2003 Pulitzer Committee to be incredibly tragic and sad. The recipients of that Pulitzer, The Boston Globe and its Spotlight Team, had an opportunity to pierce entrenched secrecy, to stir long dormant local, national and international reaction, and to produce substantive changes in the epidemic of sexual abuse from which millions in this culture have suffered. Indeed, that would have been a public service.

But the Globe let that opportunity pass for the creation of a moral panic aimed exclusively at the Catholic Church, and the Pulitzer Prize Committee chose to underwrite that fraud. It was an adventure in media narcissism, and David F. Pierre, Jr. struck the eye of that self-serving Goliath in Sins of the Press: The Untold Story of The Boston Globe's Reporting on Sex Abuse in the Catholic Church.

His publication of this book was timely. In the same year of the book’s release, Hollywood released its own version of The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer-endorsed prejudice with the film, “Spotlight” written by Thomas McCarthy, who also directed, and Josh Singer. Some have suggested that the film was on a par with the great 1976 Oscar winner, All the President’s Men that explored The Washington Post’s dogged pursuit of President Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal. The claim was ludicrous.

David Pierre posted an exclusive here two weeks ago in “Hidden Evil: The Anti-Catholic Agenda of Bishop Accountability.” It exposed another venomous venue, Bishop Accountability, which was far more interested in exploiting Catholic scandal than covering the truth about child abuse. Sins of the Press, in contrast, was focused on The Boston Globe’s coverage of Catholic scandal which was aimed solely for the purpose of destroying one of the most important pillars of Boston, Massachusetts, its Catholicism.

On page after page of Sins of the Press, Pierre presents clear and compelling evidence of the Globe’s reckless disservice to humanity in its shameless pursuit of Catholic priests. Like David Pierre’s previous books, Catholic Priests Falsely Accused, and Double Standard, Sins of the Press is right on point without its author telling us what to think about the sordid revelations it contains. He lets the facts speak for themselves, and they do, quite loudly, sometimes with echoes that resounded in my soul and psyche for days.

Mr. Pierre was not the first to take on the Globe’s reckless and destructive pursuit of Catholic priests and their due process rights. Several years before Sins of the Press was written, we published at Beyond These Stone Walls, “The Exile of Father Dominic Menna and Transparency at The Boston Globe.” Father Menna was an 81-year-old priest in the Archdiocese of Boston living out his senior years in a rectory with other priests while he served, as best he could, a parish that loved him dearly. Then out of the blue in 2007 came a single, vague allegation against him — there had never been another before or since — that The Boston Globe exploited mercilessly while allowing its readers to believe that the allegation was something that had just taken place. In truth, it was claimed to have happened 53 years earlier and like all such claims it was settled with no regard for Father Menna’s due process rights or well-being. Thanks to the Globe’s one-sided account, Father Menna was driven out of the priesthood at age 83 and died from a broken heart. Where was the Spotlight on that?

A Spotlight When We Needed a Floodlight

What The Boston Globe did, and what the Pulitzer Prize Committee honored for the Globe’s Spotlight coverage, was patently reckless, unjust, and dishonest, not only about the Catholic Church and priests, but also about the tragic and silenced majority of victims of sexual abuse. Dave Pierre’s book exposes one media tenet clearly: “If a priest didn’t do it, we’re not interested!”

The reader is left with no doubt that the harsh glare of a spotlight brought to bear by The Boston Globe was meant for a singular purpose, to isolate the Catholic Church and priesthood as a sort of special locus of sexual abuse. At the same time, the Globe accommodated by omission the prevalence of sexual abuse in other institutions throughout not only Boston, but the nation. A spotlight leaves a lot in the dark, whereas a floodlight is all-inclusive.

A case in point, one very familiar to our readers, is the story of what happened to Pornchai Moontri. The worst of it took place in New England, and the State of Maine, well within The Boston Globe’s coverage area. Pornchai Moontri was taken from his home in rural Thailand at age 11 and brought to Bangor, Maine, where he suffered years of horrific sexual abuse and violence. At one point he escaped only to be handed back over to his abuser by police. Having never been exposed to English, Pornchai could not articulate what had been happening to him. Then his mother was murdered, from all appearances by the same man who exploited Pornchai. He escaped into the streets as a teen where he lived under a bridge and homeless. During a struggle with a much larger man, Pornchai killed him in desperation, and was sent to life in prison with no defense. He ended up in a cell with me, and on April 10, 2010 he became a Catholic on Divine Mercy Sunday. As Pornchai much later wrote, “I could not believe all the stories of repressed memory and demands for huge amounts of money, by those who were accusing Catholic priests. I came to the Catholic Church for healing and hope, and found both. The grace of my recovery came from a priest who was falsely accused and I came to know that with every fiber of my being. He led me out of darkness into a wonderful light.”

With help from Clare Farr, an Australia attorney who read of Pornchai’s story and took an interest, we scoured cyberspace to find Pornchai’s abuser and bring him to justice. After reading what I wrote (linked at the end of this post), detectives from Maine came to interview Pornchai. On a second interview they brought the District Attorney. Pornchai’s abuser was found in Oregon and he was charged with 40 felony counts of child sexual abuse in Penobscot County Superior Court in Maine. On September 18, 2018 Richard Alan Bailey entered a plea of no contest on all counts. He was found guilty on all of them, but sentenced only to 18 years probation. There was no outrage, not even a sign that anyone noticed. The Boston Globe had zero interest in this story. There was just no cash to be had or Roman collar to be destroyed.

In September 2020, Pornchai was taken into custody by ICE and deported to his native Thailand. Hollywood called the Globe’s Oscar-winning film Spotlight. In a perverted sort of way, that was appropriate because it left in darkness, under shrouds of ignorance the real damage that had been done.

Losing the News

The Boston Globe Spotlight Team accomplished its goal with the creation of a perfect storm of moral panic. The paper’s spin presented every claim and accusation as demonstrably true, reported every settlement as evidence of guilt, spun decades-old claims to make them look as though they occurred yesterday, and never once questioned the financial motives of accusers.

In this arena, the Globe assisted in the continued abuse suffered by real victims by repeatedly giving a platform to personal injury lawyers who stood to pocket forty percent of every settlement wrested from a beleaguered and bludgeoned hierarchy while the millions abused in non-Catholic venues suffered in silence. The Globe’s “public service” was mostly to contingency lawyers.

Not all in the media were onboard with this. Writing for the contentious media platform, CounterPunch, columnist Joanne Wypijewski crowned her long career in journalism as a staff writer for The Nation with her own counter punch entitled “Oscar Hangover Special: Why “Spotlight” Is a Terrible Film.” For full transparency, much of her article was about the case against me. Armed with some healthy skepticism, the most important tool in her journalistic arsenal, she began her article thusly:

“I don’t “believe the victims”.

“I was in Boston in the Spring of 2002 reporting on the priest scandal, and because I know some of what is untrue, I don’t believe the personal injury lawyers or the Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” team or the Catholic “faithful” who became harpies outside Boston churches, carrying signs with images of Satan, hurling invective at congregants who’d just attended Mass, and at least once — this in my presence — spitting in the face of a person who dared dispute them.

“I don’t believe the prosecutors who pursued tainted cases or the therapists who revived junk science or the juries that sided with them or the judges who failed to act justly or the people who made money off any of this.

“And I am astonished (though I suppose I shouldn’t be) that, across the past few months, ever since Spotlight hit theaters, otherwise serious left-of-center people have peppered their party conversation with effusions that the film reflects a heroic journalism, the kind we all need more of.”

The lawyers, the Globe, and the seemingly endless parade of “John Does” all seemed to be on the same page in this, and it was always the front page. None of them reported that Father Dominic Menna, for example, never had any prior accusation, and that the one that destroyed his priesthood was claimed to have happened 53 years earlier and built on a dubious claim of repressed and recovered memory, a fraud that in this arena would go on to transform many lawyers into millionaires.

According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, less than half of Americans said that losing their local newspaper would harm civic life. Less than one third responded that they would miss their local newspaper if it just disappeared. Ken Paulson, President of the Newseum Institute’s First Amendment Center and a member of the USA Today Board of Contributors published an interesting column for USA Today entitled “News Media Lose Trust, Gain Allies.” Mr. Paulson cited a “State of the First Amendment Survey” with dismal results for those in the news media whose careers have been built upon reputable journalism. In the survey results, just 24% of respondents believe that the news media try to report the news without bias. That figure is down from 41% just a year earlier. However, 69% state that journalists in the news media should act in a watchdog role in reporting on government. That figure was down from 80% a year earlier. The first figure — the fact that only 24% of those surveyed believe the news media reports without bias — is alarming, and a record low for this decade-long poll. The second figure — indicating a decline in the sense that the media acts in a watchdog role — was surprising to Mr. Paulson who reported that “This nation’s founding generation insisted on a free press to act as a check on a strong central government … an enduring principle over centuries.” He added, however,

“Social media posts that call out unfairness and injustice don’t diminish this critical watchdog role. It just means a free press has many more allies.”

David F. Pierre, Jr. is one of those allies. His book, Sins of the Press is a David v. Goliath account that takes needed aim at The Boston Globe’s bias, and that is a good thing. The release of Spotlight, Hollywood’s version of this sordid story, felt a lot more like the Globe’s epitaph than any celebration of its dubious public service.

+ + +

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this important post. I thank David F. Pierre, Jr. and commend him for his journalistic courage and integrity. You may review his work at TheMediaReport.com.

You may also like these related posts at Beyond These Stone Walls:

Getting Away with Murder on the Island of Guam

The Lying, Scheming Altar Boy on the Cover of Newsweek

Cardinal Bernard Law on the Frontier of Civil Rights

Hidden Evil: The Anti-Catholic Agenda of Bishop Accountability

Illumination From Down Under: Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast

+ + +

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Shining a Spotlight on Media Where Lies Thrive and Truth Suffers

Mary Ann Kreitzer takes on media corruption in this brilliant article that echoes the title of her blog: ‘Les Femmes, The Truth.’

Mary Ann Kreitzer takes on media corruption in this brilliant article that echoes the title of her blog: ‘Les Femmes, The Truth.’

February 19, 2025 by Mary Ann Kreitzer

[Note from Father Gordon MacRae: The following article by Mary Ann Kreitzer was originally published at Les Femmes, The Truth. It is reprinted here with her gracious permission. I highly recommend following Mary Ann at Les Femmes, The Truth.]

+ + +

The mainstream drive-by media is, for the most part comatose and dying. The Pulitzer committee helped deliver assisted euthanasia in 2018 with its shared award to the Washington Post and New York Times for the 20-article scam-fantasy about Russiagate. Mostly based on anonymous sources, rumors, and innuendo from Trump-hating liberals, the articles lied and lied and lied again leaving wounded truth tellers in their wake like Michael Flynn. A 2022 article in the New York Post summarized the damage caused by the series:

“The liberal media had “destabilized US democracy” more than Russia ever could, by feeding left-leaning Americans a constant, false narrative that their president was a sleeper agent. Whatever your feelings about Donald Trump, it should disturb you that political opponents and bureaucrats who hated him could so easily weaponize the press to undermine the government from within.

“This Pulitzer Prize makes a mockery of the idea that journalism speaks truth to power, as it shows how the press was manipulated by the powerful. “Our republic and its press will rise or fall together,” Joseph Pulitzer once said. For the sake of both, rescind this award given in his name.”

Amen to that!

Seven years post Russiagate, we all know the lying liberal media acted as pawns in a cynical chess game to deep-six the candidacy of Donald Trump. They failed in 2016, but, with the help of election fraud, succeeded in 2020. The on-going lies and manipulation of events led voters to stop listening to the talking heads on MSNBC, CNN, and the networks. The voters rejected them because they were lying, and anyone with half a brain knew it.

But Trump isn’t the only victim of the corrupt legacy media. Anyone can become the target. We’ve seen the media used against conservatives, the J6ers, pro-lifers, homeschoolers, and, with a special vengeance, Catholic priests. The clergy sex abuse scandals involved a fraction of priests, but the hysteria coupled with greed turned justice on its head. Every man in a Roman collar became the target of unscrupulous “victims” and ambulance-chasing lawyers who often chose dead priests to accuse with little or no evidence.

To this day, I have anti-Catholic readers who comment on my blog with vicious generalizations about priests. Obviously I don’t post their screeds.

Don’t get me wrong. There were certainly real and grim cases of abuse and disgraceful cover-ups by corrupt bishops who moved the guilty around allowing them to abuse again. Those priests and bishops should be in jail. But in the hysteria that accompanied the real evil, many innocent priests were accused including those long dead who could not defend themselves, a clever strategy by greedy liars for robbing the Church.

Which brings me to Fr. Gordon MacRae’s article last week at Beyond These Stone Walls.

Father MacRae’s article links to several others that shine a real spotlight (unlike the media’s) on the money-hungry lawyers eager for prime rib from the cash cow of the Church. In one of the linked articles, “Due Process for Accused Priests,” Fr. MacRae wrote:

“A New Hampshire contingency lawyer recently brought forward his fifth round of mediated settlement demands. During his first round of mediated settlements in 2002 — in which 28 priests of the Diocese of Manchester were accused in claims alleging abuse between the 1950s and 1980s — the news media announced a $5.5 million settlement. The claimants’ lawyer, seemingly inviting his next round of plaintiffs, described the settlement process with the Manchester diocese: “During settlement negotiations, diocesan officials did not press for details such as dates and allegations for every claim. I’ve never seen anything like it.” (NH Union Leader, Nov. 27, 2002). “Some victims made claims in the last month, and because of the timing of negotiations, gained closure in just a matter of days.” (Nashua Telegraph, Nov. 27, 2002).

“That lawyer’s contingency fee for the first of what would evolve into five rounds of mediated settlements was estimated to be in excess of $1.8 million. At the time this first mediated settlement was reached in 2002, New Hampshire newspapers reported that at the attorney’s and claimants’ request, the diocese agreed not to disclose their names, the details of abuse, or the amounts of individual settlements.

“In contrast, the names of the accused priests — many of whom were deceased — were publicized by the Diocese in a press release. Despite the contingency lawyer’s widely reported amazement that $5.5 million was handed over with no details or corroboration elicited by the diocese, the claims were labeled “credible” by virtue of being settled. Priests who declared the claims against them to be bogus — and who, in two cases, insisted that they never even met these newest accusers — were excluded from the settlement process and never informed that a settlement had taken place. The priests’ names were then submitted to the Vatican as the subjects of credible allegations of abuse. The possible penal actions — for which there is no opportunity for defense or appeal — include possible administrative dismissal from the priesthood, but without any of the usual vestiges of justice such as a discovery process, a presumption of innocence, or even a trial.”

Fr. MacRae remains in jail after 30 years because he refused to lie and take a plea bargain bribe to admit guilt in exchange for a drastically reduced sentence. He took the hard road of truth and remains in prison like so many of the saints. He never faced the beasts in the colosseum, just the vultures in the witness box.

Unfortunately, many journalists aren’t interested in the truth or in presenting an unbiased story — i.e., straight reporting. They happily feed convenient lies to the public or omit relevant facts to uphold their personal agendas. And that’s the point of Father MacRae’s article last week linking to another article from 2016 that described why the Spotlight film about Paul Shanley and abuse in Boston was terrible. The journalist, JoAnn Wypijewski, described both Fr. Shanley’s case and Fr. MacRae’s. The differences were striking: a gay, rebel priest vs. a faithful, orthodox priest. The similar situation was that both were convicted at witch trials on no evidence but hysteria. Another similarity, neither would accept a plea deal. Fr. MacRae writes:

“Paul Shanley stood for and did all manner of things that on their face were seen by some as dishonorable and disrespectful of his priesthood and his faith. But he was not on trial for those things. He was on trial for very specific offenses for which there was no evidence whatsoever beyond his reputation. All objective observers who look past his personal morality long enough to see the facts conclude that he was innocent of the crimes for which he was then in prison at age 84. We don’t have to like him to see that the Shanley trial was a sham.

“Ms. Wypijewski’s CounterPunch juxtaposition of all this with the story of my own trial and imprisonment was jarring at best, but only because I have lived under the cloud of false witness for so long that to see it again in print assails me. The author’s revelation that this was all driven by the hysteria of moral panic surrounding the very idea of priestly abusers, and not evidence — for there was no evidence — drove the accusations, drove the trial, drove the media coverage, and drove me into prison. “MacRae got sixty-seven years for refusing to lie,” she wrote. “Let that sink in.”

True journalism is hard to find these days. Some students say they choose journalism because they want to “change things.” That, however is not the purpose of journalism. It’s to seek the truth through unbiased reporting of events that look at all sides without prejudice. We aren’t seeing much of that these days which means it’s incumbent on us to uphold the truth and avoid leaping to conclusions or rash judgments.

I hope you will read Father MacRae’s article and the others to which he links. His story is truly a lesson in the value of truth and the obligation to do the research. Our mind is called the seat of judgment. We would do well to remember that making clear and lucid judgments requires us to demand facts and not make decisions based on hysteria and moral panic. There are too many examples of that. I’ll offer just one. Remember Nick Sandman and the Covington students at the Lincoln Memorial after the March for Life in 2019. Remember the false accusations of their abuse of Native American grifter and liar, Nathan Phillips. The Kentucky bishops with no evidence at all leaped on the guilty bandwagon as did right-to-life groups and many in Catholic media. We should never forget that lesson!

I’m offering the Litany of the Holy Spirit today that Paul Shanley used his time in prison to examine his life, repent of his true sins, and embrace the fullness of the Catholic faith. Prison has a way of focusing the mind. Perhaps for Shanley, his cell became a haven of grace. And I will especially pray for Fr. Gordon MacRae, a faithful priest of God, whose prison cell has been a source of grace for many.

Holy Spirit Who proceeds from the Father and the Son, enter our hearts.

+ + +

Note from Fr Gordon MacRae: I thank Mary Ann Kreitzer for her fine writing and fidelity to Truth. I again hope you will check out her outstanding Catholic blog, Les Femmes, The Truth.

I am also pleased to report that our story has been growing legs of late. We appear in a segment of the Australian site, Wrongful Convictions Report.

You may also like these related articles from Beyond These Stone Walls:

The Exile of Father Dominic Menna and Transparency at The Boston Globe

To Fleece the Flock: Meet the Trauma-Informed Consultants

Cardinal Bernard Law on the Frontier of Civil Rights

Pell Contra Mundum: Cardinal Truth on the Synod

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

A Cold Shower for a Spotlight Oscar Hangover

The film "Spotlight" won the Academy Award for Best Picture on February 28, 2016. Since then journalist JoAnn Wypijewski has debunked it as a script for moral panic.

The film "Spotlight" won the Academy Award for Best Picture on February 28, 2016. Since then journalist JoAnn Wypijewski has debunked it as a script for moral panic.

February 12, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

[ Note from Father MacRae: I should have been more attentive in explaining this post this week. It is not so much a reprint as a restoration. A noted journalist had written a wonderful piece about the "Spotlight" film's Academy Award for Best Picture nine years ago. The writer, JoAnn Wypijewski, heralded an entirely new view of the film, which caused me to want to rewrite this post. ]

For some purveyors of journalism in America, the standard for modern news media seems to come down to “whoever screams longest and loudest is telling the truth.” Taking a position against a tidal wave of “availability bias” — a phenomenon I once described in a Catalyst article, “Due Process for Accused Priests” — might get a writer shouted down in a blast of hysteria masked as journalism.

But that may be changing. A post I wrote a few years ago, “The Lying, Scheming Altar Boy on the Cover of Newsweek,” a story that exposes a Catholic sex abuse fraud, has generated an unexpected response. At this writing, it has been shared thousands of times on social media, and has drawn readers by the thousands every day since it was posted.

There is nothing in that post, however, that screams out drama from the rooftops. If anything, it is subtle, reasoned, and unemotional. I am sometimes criticized for telling important stories without much emotional hype. Sometimes my friends become irritated with my lack of ranting and raving, but I must come down on the side of rational discourse when I write.

That lesson in the difference between responsible journalism and moral panic has been driven home again. I have had to add a few names to my short list of “News Media Spinal Columns.” Some writers exemplify courage and integrity by rationally exposing important stories despite a scandal-hungry news media that prefers moral panic to moral truths. Some have pushed back against that tide admirably, and though the list is short, today I have to add the name of another journalist with a spinal column.

On Sunday evening, February 28, 2016 I opted for Downton Abbey on PBS instead of the Academy Awards. Like most PBS productions, Downton Abbey had no commercial breaks so I did not switch over for even a peek at that annual diversity-challenged nod to Hollywood narcissism known as the Oscars.

I was not at all surprised to learn that “Spotlight” won the Oscar for Best Picture, its sole award out of six nominations. It is a sign of Oscar’s elitist finger on the pulse of common humanity that only two percent of viewers thought this was “Best Picture” in a USA Today study of exit interviews.

JoAnn Wypijewski has a very different take, not so much on the film itself, but on the integrity, of the story behind it and its damage to the art of journalism as rational reporting gave way to emotion. I cannot tell you how disappointing it was to read a review by Kathryn Jean Lopez at National Review Online who surrendered reasoned journalism right in paragraph one:

“I cried watching that movie. I looked around and saw sorrow. I couldn’t help wondering if someone around me had been hurt by someone who professed to be a man of God.”

“But, hey, lighten up. It’s just a movie,” wrote two reviewers in the The New York Times (which, by the way, owned The Boston Globe during its 2002 Spotlight Team investigation). “And they don’t give an Oscar for telling the truth.”

CounterPunch

On the day after the Oscars, at least five people sent me messages with a link foreboding, “You Need to See This!” Each warned that I am mentioned extensively in a controversial article by JoAnn Wypijewski at CounterPunch, a left-leaning news site that lives up to its name. Entirely unaccustomed to being treated justly by the media of the left in all this, my first thoughts on the article were not happy ones. Then the final message we checked was from the author herself with a link to “Oscar Hangover Special: Why’ ‘Spotlight’ Is a Terrible Film”:

“Fr. MacRae, I suspect you will think this intemperate… but then being in prison has given you an expansive view of polite company. I wrote this [see link] on the heels of the Oscars. I think you will like some of it, at least.”

I had no input into this article and no prior awareness of it. It does not represent my point of view at all, but rather is written solely from the point of view of the public record, seen through a fair and just set of journalistic eyes. The article was read once to me via telephone, and my knee jerk reaction was to keep it to myself. Then it was printed and sent to me, and I have since read it carefully twice. It’s tough stuff, and it made me grimace more than once, but mostly for its brutal honesty.

On first hearing the article, I have to admit that I didn’t much like being thrown together with the story of Father Paul Shanley, a notorious Boston priest with a long history of ecclesiastical rebellion. I suspect this is what the author meant by prison giving me “an expansive view of polite company.” I guess she understands that in some other circumstance, I may not choose to stand next to a lightning rod in a perfect storm.

But I know and admit that my gag reflex of umbrage was unjust, as I know that the case against Paul Shanley was unjust. He was tried not based on evidence of a real crime, but solely on the basis of his reputation. That was the only vehicle in which an utterly unbelievable, scientifically unsupportable claim of repressed and recovered memory could have been sold to an otherwise rational set of jurors.

First, throughout the 1970s, The Boston Globe, celebrated Paul Shanley as a notorious, pro-gay, in-the-Church’s-face “Street Priest.” Then, when it better suited the agenda of editors, the Globe turned on him. Shanley was tried in the pages of the Globe before he set foot in any court of law. He was sacrificed to a story that is not even plausible, and in its telling, journalistic integrity was sacrificed as well.

“Let That Sink In”

Paul Shanley stood for and did all manner of things that on their face were seen by some as dishonorable and disrespectful of his priesthood and his faith. But he was not on trial for those things. He was on trial for very specific offenses for which there was no evidence whatsoever beyond his reputation. All objective observers who look past his personal morality long enough to see the facts conclude that he was innocent of the crimes for which he was then in prison at age 84. We don’t have to like him to see that the Shanley trial was a sham.

Ms. Wypijewski’s CounterPunch juxtaposition of all this with the story of my own trial and imprisonment was jarring at best, but only because I have lived under the cloud of false witness for so long that to see it again in print assails me. The author’s revelation that this was all driven by the hysteria of moral panic surrounding the very idea of priestly abusers, and not evidence — for there was no evidence — drove the accusations, drove the trial, drove the media coverage, and drove me into prison. “MacRae got sixty-seven years for refusing to lie,” she wrote. “Let that sink in.”

The truth is that most of you now reading this have already let that sink in while others, including others in the Church, have settled for moral panic. This is why the late Father Richard John Neuhaus, Publisher and Editor of First Things magazine, wrote that my imprisonment “reflects a Church and a justice system that seem indifferent to justice.” This is why I need you to share this post and the CounterPunch article linked at the end.

Otherwise very reasonable Catholics on both the left and right have used the scandal of accused priests for their own agendas and ends with no regard for evidence, for justice, or for the most fundamental rights of their priests. The blind, self-righteous judgment of this “voice of the faithful” was the soil in which moral panic grew. Let that sink in, too.

The news media has done the same, and JoAnn Wypijewski has documented this masterfully. What The Boston Globe did was not journalism. It came as no surprise, in the years to follow the Spotlight revelations, that the Globe’s owner, The New York Times, became desperate to sell it. Several years ago the Globe was purchased by John Henry, owner of the Boston Red Sox. The New York Times let the Globe go for less than seven cents on the dollar on their original purchase price of $1.1 billion. It was sold by the Times for $70 million. Bottom line: The Boston Globe is dying. The Catholic Church is not.

Globe to shutter Crux site, shift BetaBoston

by Hiawatha Bray, Globe Staff, Casting the Second Stone2016

The Boston Globe said Friday that it will shut down Crux, the newspaper’s online publication devoted to news and commentary on the Roman Catholic Church. Crux will halt publication on April 1, and several employees will be laid off.

In a memo sent to Globe employees Friday, Globe editor Brian McGrory wrote “we’re beyond proud of the journalism and the journalists who have produced it, day after day, month over month, for the past year and a half.” But McGrory added, “We simply haven’t been able to develop the financial model of big-ticket, Catholic-based advertisers that was envisioned when we launched Crux back in September 2014.”

McGrory said that the Crux site will be handed over to associate editor and columnist John Allen, a veteran reporter on Catholic affairs. McGrory said that Allen “is exploring the possibility of continuing it in some modified form, absent any contribution from the Globe.” Crux editor Teresa Hanafin will stay in the newsroom, probably at bostonglobe.com, the paper’s online home.

Casting the Second Stone

In “Casting the First Stone: What Did Jesus Write On the Ground?,” I described the limits that the Hebrew Scriptures imposed on the process of accusing, judging, and destroying our fellow human beings. Only with evidence and witnesses, and there had to be at least two, could the first stone be cast according to the Law of Moses (Deuteronomy 17:17). Only then could the mob be justified in joining in.

But in the creation of a moral panic, such as that which Hollywood recently endorsed at the Academy Awards, no such limits on public stoning by the mob are deemed necessary. The Laws of God are not to be found in the credits of a Hollywood production, and for many in modern Western Culture, Hollywood is now the final arbiter of truth and justice. Are you really prepared to accept a lecture on morality and justice taught by the news media with an endorsement from Hollywood? Some — even among Catholic priests and bishops — have learned that the best way to avoid being targeted by a witch hunt is to join in with its inevitable stoning.

Regarding the CounterPunch article taken as a whole, JoAnn Wypjewski is wrong about one thing. I did not “like some of it, at least.” I liked all of it! I liked it not because it is comfortable to read — it is not — but because it is the truth, because it is written by a person whose integrity as a journalist took precedence over what those on her ideological side of the fence demand from her. I like it because very early on in the article she risked making herself a lightning rod for the media left by challenging its availability bias:

“I am astonished that, across the past few months, ever since ‘Spotlight’ hit theaters, otherwise serious left-of center people have peppered their party conversation with effusions that the film reflects a heroic journalism, the kind we all need more of… What editor Marty Baron and the Globe sparked with their 600 stories and their confidential tip line for grievances was not laudatory journalism but a moral panic, and unfortunately for those who are telling the truth, truth was its casualty.”

Writing for The Wall Street Journal recently, author Carol Tavris described the devastation typically left in the wake of a moral panic:

“How do you convey to the next generation the stupidity, the rush to judgment, the breathtaking cruelty, the self-righteousness, the ruined lives, that every hysterical epidemic generates? On the other hand, understanding a moral panic requires perspective-distance from the emotional heat of anger and anxiety.”

— “A Very Model Moral Panic,” WSJ.com, August 7, 2015

To date the CounterPunch article has been shared thousands of times on social media. This is of utmost importance because it lets all media know that this is an important story that has been neglected by the mainstream media.

I therefore implore you to share this post, and to read and share this important article by JoAnn Wypijewski: “Oscar Hangover Special: Why ‘Spotlight’ Is a Terrible Film.”

+ + +

NOTE TO READERS: Father Gordon MacRae is now publishing an occasional article on X (formerly Twitter). His first article there is linked below. We invite our readers to follow him on X @TSWBeyond.

xAI Grok and Fr. Gordon MacRae on the True Origin of Covid-19

You may also like these recommended posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

The Anatomy of a Sex Abuse Fraud

The Dark Night of a Priestly Soul

Unjustly in Prison for 30 Years: A Collision of Fury and Faith

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Cardinal Bernard Law on the Frontier of Civil Rights

Former Boston Archbishop, Cardinal Bernard Law was vilified by The Boston Globe and SNAP, but before that he was a champion of justice in the Civil Rights Movement.

Former Boston Archbishop, Cardinal Bernard Law was vilified by The Boston Globe and SNAP, but before that he was a champion of justice in the Civil Rights Movement.

June 19, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

Note from Fr MacRae: I first wrote this post in November 2015. I wrote it in the midst of a viral character assassination of a man who had become a convenient scapegoat for what was then the latest New England witch hunt. That man was Cardinal Bernard Law, Archbishop of Boston. I have to really tug hard to free this good man’s good name from the media-fueled availability bias that so mercilessly tarnished it back then. A good deal more has come to light, and I get to have the last word.

By coincidence, and it was not planned this way, but the date of this revised reposting is June 19, 2024, the day that the United States commemorates the emancipation of African American slaves on June 19, 1865 in Galveston, Texas. As you will read herein, Cardinal Bernard Law was a national champion in the cause for Civil Rights and racial equality.

+ + +

Four years after The Boston Globe set out to sensationalize the sins of some few members of the Church and priesthood, another news story — one subtly submerged beneath the fold — drifted quietly through a few New England newspapers. After a very short life, the story faded from view. In 2006, Matt McGonagle resigned from his post as assistant principal of Rundlett Middle School in Concord, New Hampshire. Charged with multiple counts of sexually assaulting a 14-year-old high school student six years before, McGonagle ended his criminal case by striking a plea deal with prosecutors. McGonagle pleaded guilty to the charges on July 28, 2006.

He was sentenced to a term of sixteen months in a local county jail. An additional sentence of two-and-a-half to five years in the New Hampshire State Prison was suspended by the presiding judge in Merrimack County Superior Court — the same court that declined to hear evidence or testimony in my habeas corpus appeal in 2013 after having served 20 years in prison for crimes that never took place.

In a statement, Matt McGonagle described the ordeal of being prosecuted. He said it was “extraordinarily difficult,” and thanked his “many advocates” who spoke on his behalf. In the local press, defense attorney James Rosenberg defended the plea deal for a sixteen month county jail sentence:

“The sentence is fair, and accurately reflects contributions that Matt has made to his community as an educator.”

— Melanie Asmar, “Ex-educator pleads guilty in sex assault,” Concord Monitor, July 29, 2006

Four years earlier, attorney James Rosenberg was a prosecutor in the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office from where he worked to prosecute the Diocese of Manchester for its handling of similar, but far older claims against Catholic priests.

The accommodation called for in the case of teacher/principal Matt McGonagle — an insistence that he is not to be forever defined by the current charges against him — was never even a passing thought in the prosecutions of Catholic priests. Those cases sprang from the pages of The Boston Globe, swept New England, and then went viral across America. The story marked The Boston Globe’s descent into “trophy justice.”

Cardinal Sins

I have always been aware of this inconsistency in the news media and among prosecutors and some judges, but never considered writing specifically about how it applied to Cardinal Bernard Law until I read Sins of the Press, a book by David F. Pierre, Jr. On page after page it cast a floodlight on The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer-endorsed lynching of Cardinal Law, offered up as a scapegoat for The Scandal and driven from Boston by the news media despite having never been accused, tried, or convicted of any real crime.

Does the “lynching of Cardinal Law” seem too strong a term? Historically, the word “lynching” came into the English lexicon from the name of Captain William Lynch of Virginia who acted as prosecutor, judge and executioner. He became notorious for his judgment-sans-trial while leading a band to hunt down Loyalists, Colonists suspected of loyalty to the British Crown in the War for Independence in 1776.

The term applies well to what started in Boston, then swept the country. Most of those suspected or accused in the pages of The Boston Globe, including Cardinal Bernard Law, were never given any trial of facts. As I recently wrote in, “To Fleece the Flock: Meet the Trauma-Informed Consultants,” many of the priests were deceased when accused, and many others faced accusations decades after any supportive evidence could be found, or even looked for. The Massachusetts Attorney General issued an astonishing statement given short shrift in the pages of The Boston Globe:

“The evidence gathered during the course of the Attorney General’s sixteen-month investigation does not provide a basis for bringing criminal charges against the Archdiocese and its senior managers.”

— Commonwealth of Massachusetts Attorney General Thomas Reilly, “Executive Summary and Scope of the Investigation,” July 23, 2003

So I decided to explore the story of Cardinal Bernard Law for Beyond These Stone Walls. When I first endeavored to write about him, he had been virtually chased from the United States by some in the news media and so-called victim advocates deep into lawsuits to fleece the Church. Though not intended originally, my post was to be published on November 4, 2015, which also happened to be Cardinal Law’s 84th birthday.

When I wrote of my intention to revisit the story of Cardinal Bernard Law from a less condemning perspective, it sparked very mixed feelings among some readers. A few wrote to me that they looked forward to reading my take on the once good name of this good priest. A few taunted me that this was yet another “David v Goliath” task. Others wrote more ominously, “Don’t do it, Father! Don’t step on that minefield! What if they target you next?” That reaction is a monument to the power of the news media to spin a phenomenon called “availability bias.”

A while back, I was invited by Catholic League President Bill Donohue to contribute some articles for Catalyst, the Journal of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. My second of two articles appeared in the July/August 2009 issue just as Beyond These Stone Walls began. It was entitled “Due Process for Accused Priests” and it opened with an important paragraph about the hidden power of the press to shape what we think:

“Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for his work on a phenomenon in psychology and marketing called ‘availability bias.’ Kahneman demonstrated the human tendency to give a proposition validity just by how easily it comes to mind. An uncorroborated statement can be widely seen as true merely because the media has repeated it. Also in 2002, the Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal swept out of Boston to dominate news headlines across the country….”

This is exactly what happened to Cardinal Law. There was a narrative about him, an impression of his nature and character that unfolded over the course of his life. I spent several months studying that narrative and it is most impressive.

Then that narrative was replaced by something else. With a target on his back, the story of Cardinal Law was entirely and unjustly rewritten by The Boston Globe. Then the rewrite was repeated again and again until it took hold, went viral, and replaced in public view the account of who this man really was.

Even some in the Church settled upon this sacrificial offering of a reputation. Perhaps only someone who has known firsthand such media-fueled bias can instinctively recognize it happening. Suffice it to say that I instinctively recognized it. I offer no other defense of my decision to visit anew the first narrative in the story of who Bernard Law was. If you can set aside for a time the availability bias created around the name of Cardinal Bernard Law, then you may find this account to be fascinating, just as I did.

From Harvard to Mississippi

As this account of a courageous life and heroic priesthood unfolded before me, I was eerily reminded of another story, one I came across many years ago. It was the year I began to seek something more than the Easter and Christmas Catholicism I inherited. It was 1968, and I was fifteen years old in my junior year at Lynn English High School just north of Boston. Two champions of the Civil Rights Movement I had come to admire and respect in my youth — Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy — had just been assassinated. And just as my mind and spirit were being shaped by that awful time, I stumbled upon something that would refine for me that era: the great 1963 film, The Cardinal.

Based on a book of the same name by Henry Morton Robinson (Simon & Schuster 1950), actor Tom Tryon portrayed the title role of Boston priest, Father Stephen Fermoyle who rose to become a member of the College of Cardinals after a heroic life as an exemplary priest. It was the first time I encountered the notion that priesthood might require courage, and I wondered whether I had any. I was fifteen, sitting alone at Mass for the first time in my life when this movie sparked a scary thought.

Father Fermoyle was asked by the Apostolic Nuncio to tour the southern United States “between the Great Smokies and the Mississippi River” — an area known for anti-Catholic prejudice. He was tasked with writing a report on the state of the Catholic Church there during a time of great racial unrest.

In the script (and in the book which I read later) Mississippi Chancery official, Monsignor Whittle (played in the film by actor, Chill Wills) was fearful of the racist, anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan. He tried to dissuade Father Fermoyle from making any waves, but his mere presence there would set off a tidal wave of suspicion. In a horrific scene, Father Fermoyle was kidnapped in the night, blindfolded, and driven to the middle of a remote field — a field where many young black men had disappeared.

His blindfold removed, he found himself surrounded by men in sheets and white hoods, illuminated by the light of a burning cross. Father Fermoyle was given a crucifix and ordered to spit on it or face the scourging of Christ. Henry Morton Robinson’s book conveys the scene:

“He held the crucifix between thumb and forefinger, lofting it like a lantern in darkness…. Ancient strength of martyrs flowed into Stephen’s limbs. Eyes on the gilt cross, he neither flinched nor spoke. [The music played] ‘In Dixieland I’ll take my stand.’ Stephen prayed silently that no drop of spittle, no whimpering plea for mercy, would fall from his lips before the end… The sheeted men climbed into their cars. Not until the last taillight had disappeared had Stephen lowered the crucifix.”

— The Cardinal, pp 412-413

This could easily have been a scene from the life of Father Bernard Law. Born on 4 November 1931 in Torreon, Mexico, Bernard Francis Law spent his bilingual childhood between the United States, Latin America, and the Virgin Islands. His father was a U.S. Army Captain in World War II and Bernard was an only child. Very early in life, he learned that acceptance does not depend on race, or color, or creed, and once admonished his classmates in the Virgin Islands that “Never must we let bigotry creep into our beings.”

At age 15, Bernard read Mystici Corporis, a 1943 Encyclical of Pope Pius XII that Bernard later described as “the dominant teaching of my life.” He was especially touched by the language of inclusion of a heroic Pope in a time of great oppression. The encyclical was banned in German-occupied Belgium for “subversive” lines connecting the Mystical Body of Christ with the unity of all Christians, transcending barriers such as race or politics.

As a weird aside, I was in shock and awe as I sat typing this post when I asked out loud, “How could I find a copy of Mystici Corporis while stuck in a New Hampshire prison cell?” Then our convert friend, Pornchai Moontri jumped from his bunk, pulled out his footlocker containing the sum total of his life, and handed me a heavily highlighted copy of the 1943 Encyclical. I haven’t yet wrapped my brain around that, but it’s another post for another time.

While attending Harvard University, Bernard Law found a vocation to the priesthood during his visits to Saint Paul’s Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After graduating from Harvard in 1953, the year I was born, a local bishop advised him that Boston had lots of priests and he should give his talents to a part of the Church in need. At age 29, Father Bernard Law was ordained for what was the Diocese of Natchez-Jackson, Mississippi.

Standing before the Mask of Tyranny

The year was 1961. The Second Vatican Council would soon open in Rome, and the Civil Rights Movement was gathering steam (and I do mean steam!) in the United States, Father Law immersed himself in both. A Vicksburg lawyer once remarked that Father Law “went into homes as priests [there] had never done before.” With a growing reputation for erudition and bridge building on issues many others simply avoided, Bernard was summoned by his bishop to the State Capital to become editor of the diocesan weekly newspaper, then called The Mississippi Register.

It was there that the courage to proclaim the Gospel took shape in him, and became, along with his brilliant mind, his most visible gift of the Holy Spirit. Another young priest of that diocese noted that Father Law’s racial attitudes — shaped by his childhood in the Virgin Islands — were different from those of most white Mississipians. “He felt passionately about racial justice from the first moment I knew him,” the priest wrote. “It wasn’t a mere following of teaching, it came from his heart.”

I know many Mississippi Catholics today — including many who read Beyond These Stone Walls — but in the tumultuous 1960s, Catholics were a small minority in Mississippi. They were also a target for persecution by the Ku Klux Klan which was growing in both power and terror as the nation struggled with a burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.

An 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision in “Plessy v. Ferguson” had defined the doctrine of “separate but equal” as a Constitutional nod to racial segregation, but in 1954 in “Brown v. Board of Education,” the Supreme Court based a landmark desegregation ruling on solid evidence that “separate” was seldom “equal.” Opposition to the ruling grew throughout the South, and so did terrorist Klan activities. In 1955, the murder of a black Mississippi boy, 14-year-old Emmett Till, rocked the state and the nation, as did the acquittal of his accused white killers.

This was the world of Father Bernard Law’s priesthood. Up to that time, the diocesan newspaper, The Mississippi Register, had been visibly timid on racial issues, but this changed with this priest at the helm. In June of 1963 he wrote a lead story on the evils of racial segregation citing the U.S. Bishops’ 1958 “Statement on Racial Discrimination and the Christian Conscience.”

One week later, the respected NAACP leader Medgar Evers was gunned down outside his Jackson, Mississippi home. Both Father Law and (then) Natchez-Jackson Bishop Richard Gerow boldly attended the wake for Medgar Evers under the watchful eyes of the Klan. Father Law’s next issue of The Mississippi Register bore the headline, “Everyone is Guilty,” citing a statement by his Bishop that many believe was written by Bernard Law:

“We need frankly to admit that the guilt for the murder of Mr. Evers and the other instances of violence in our community tragically must be shared by all of us… Rights which have been given to all men by the Creator cannot be the subject of conferral or refusal by men.”

Father Law and Bishop Gerow were thus invited to the White House along with other religious leaders to discuss the growing crisis in Mississippi with President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Later that summer, Father Law challenged local politicians in The Mississipi Register for their lack of moral leadership on racial desegregation, stating “Freedom in Mississippi is now at an alarmingly low ebb.” Massachusetts District Judge Gordon Martin, who was a Justice Department attorney in Mississippi at that time, once wrote for The Boston Globe that Father Law…

“…did not pull his punches, and the Register’s editorials and columns were in sharp contrast with the racist diatribes of virtually all of the state’s daily and weekly press.”

Later that year, Father Law won the Catholic Press Association Award for his editorials. In “Freedom Summer” 1964, when three civil rights workers were missing and suspected to have been murdered, Father Bernard Law openly accepted an invitation to join other religious leaders to advise President Lyndon Johnson on the racial issues in Mississippi. When the bodies of the three slain young men were found buried at a remote farm, the priest boldly issued a challenge to stand up to the crisis:

“In Mississippi, the next move is up to the white moderate. If he is in the house, let him now come forward.”

Later that year Father Law founded and became Chairman of the Mississippi Council on Human Relations. Then the home of a member, a rabbi, was bombed. Then another member, a Unitarian minister, was shot and severely wounded. The FBI asked Father Law to keep them apprised of his whereabouts, and Bishop Gerow, fearing for his priest’s safety, ordered him from the outskirts of Jackson to the Cathedral rectory, but Bernard Law feared not.

Cardinal Law’s life and mine crossed paths a few times over the course of my life as a priest. I mentioned above that while attending Harvard University, Bernard Law found his vocation to the priesthood during visits to Saint Paul’s Church in Cambridge. Many years later, in 1985, my uncle, Father George W. MacRae, SJ, the first Roman Catholic Dean of Harvard Divinity School and a renowned scholar of Sacred Scripture, passed away suddenly at the age of 57. I was a concelebrant at his Mass of Christian Burial at Saint Paul’s Church in Cambridge. Concelebrating with me was Cardinal Bernard Law where his life as a priest first took shape.

In 2013, The New York Times sold The Boston Globe for pennies on the dollar.

On December 20, 2017, Cardinal Bernard Law passed from this life in Rome.

Oh, that such priestly courage as his were contagious, for many in our Church could use some now. Thank you, Your Eminence, for the gift of a courageous priesthood. Let us not go gentle into The Boston Globe’s good night.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: I am indebted for this post to the book, Boston’s Cardinal : Bernard Law, the Man and His Witness, edited by Romanus Cessario, O.P. with a Foreword by Mary Ann Glendon (Lexington Books, 2002).

You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Saint John Paul the Great: A Light in a World in Crisis

Pell Contra Mundum: Cardinal Truths about the Synod

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

A Sex Abuse Cover-up in Boston Haunts the White House

With The Boston Globe Spotlight focused only on Catholic priests, sex abuse by a top Boston police union official was covered up all the way to the 2021 White House.

When The Boston Globe Spotlight focused only on Catholic priests, sex abuse by a top Boston police union official was covered up all the way to the 2021 White House.

Our Canadian guest writer, Father Stuart MacDonald, posted a thoughtful comment on my recent post, “Cardinal Sins in the Summer of Media Madness.” He pointed out a sobering fact. Former police officer Derek Chauvin, who now stands convicted in the murder of George Floyd, was sentenced to exactly one-third of the sentence I am serving for crimes that never took place. Father Stuart’s insightful comment was followed by one from another frequent guest writer, Ryan A. MacDonald, no relation to Father Stuart.

Their comments are very much worth a return visit to that post. The tragic death of George Floyd at the hands of Derek Chauvin in sight of three other officers launched a movement across America to defunct police. It also led to all of the events described in the post cited above.

You might think that in my current location, a movement like #DefundPolice would find lots of sympathy and even some vocal support. The truth is just the opposite. No one understands the need for police in our society more than a prisoner. As one friend here, an African American, put it: “Knowing the truth about some of the guys around me, the last thing I want to see is them and my family living in the same place without police.”

I reflected that same sentiment, and others like it, in my own response to the #DefundPolice movement that was spawned by the death of George Floyd. It was a post written in the heat of that awful riotous summer of 2020. It was “Don’t Defund Police! Defund Unions that Cover Up Corruption.”

As that post revealed, former Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin had multiple excessive force complaints in his personnel file. Thanks to the so-called “Blue Wall” and the misguided advocacy of the local public sector police union, none of the prior complaints ever became public. Had they been known, George Floyd may be alive today and Derek Chauvin may not be facing prison.

Others among my friends have advised me not to overlook the fact that Mr. Floyd was alleged to have committed a crime that day — an attempt to pass a counterfeit $20 bill. Even if true, this is not relevant. Americans do not face death over a fake $20 bill. The George Floyd story unmasked racial prejudice in the way policing is sometimes done on the streets of America. We will be a stronger and better people for the hard soul-searching and policy building needed to address this.

I write all of the above to stress that I am not in any way against police. Like my friend mentioned above, knowing some of the men with whom I now live deepens my appreciation for the many dedicated police officers who serve and protect our communities.

The account I am about to present should not be understood as just another “dirty cop” story. It is better seen as a cautionary tale of public corruption that extends beyond police to infiltrate and compromise many of the once-respected institutions on which our culture is built. The corruption you will read about here is as much that of partisan politics and the news media as it is about police. It is a Boston story. It took place in my own home town.

While the Spotlight Was on Catholic Scandal

This account is unrelated to the sordid stories of Catholic scandal in which we have been immersed for two decades, but it must begin there with a July, 2010 post, “The Exile of Fr. Dominic Menna and Transparency at The Boston Globe.”

I highly recommend that post for the back story of what was happening to many Catholic priests as the age of cancel culture was just taking shape. The story might infuriate you. It should. In 2010, Father Dominic Menna was a much beloved 80-year-old Boston priest who was suddenly accused of molesting a minor 51 years earlier when he was 29 years old in 1959. Like every accused priest since The Scandal first gripped Boston and spread from there across the land, the elderly Father Menna was put out into the street.

You could not tell from reading The Boston Globe accounts of the case that none of this story took place in the present. The Globe had a subtle way of presenting every decades-old claim as though it happened in the here and now. Father Menna just disappeared into the night with no recourse to protect himself or his priesthood. There were no groups forming such as “Stand with Father James Parker” or “Stand with Canceled Priests” when the stench of injustice was in any way related to suspicions of sexual abuse.

Even some Catholic entities have thanked The Boston Globe and its pernicious Spotlight Team for doggedly pursuing the files of priests accused and for publishing every lurid detail, true or not. The Globe helped create a mantra that impacted the civil rights of all priests who, since the Bishops’ Dallas Charter of 2002, have been considered “guilty for being accused.” The trajectory lent itself in 2010 to “The Exile of Fr. Dominic Menna” with few questions asked. The details in that post are staggering for any Catholic who still cares about justice. One of the truths exposed in that post is about all that is left in darkness when a spotlight is used on a topic that requires a floodlight. It is about something that was happening off-the-radar in Boston while The Boston Globe and its Spotlight Team celebrated an Academy Award for Best Picture in the category of Public Service.

If not for the Globe’s hammering away at priests, the people of Boston might have been shocked in the summer of 2020 when Patrick Rose, a Boston police officer and former president of the Boston police union, was charged with 33 counts of molesting children. Bostonians might have been further shocked to learn that the behaviors which led to his arrest extended all the way back to 1995 and were known by officials in the Boston police, their public sector union, and others who helped to keep it all secret.

In 1995, just months after I was on trial in nearby New Hampshire, Patrick Rose was arrested and charged with child sexual abuse. He was placed on administrative leave by the Boston Police Department. The Boston Globe today reports that the charges were dropped in 1996 when the accuser recanted her account under pressure from Rose. Later in 1996, however, a Boston Police Internal Affairs investigation reported that the charge “was sustained” and relayed to supervisors.

Despite this, Patrick Rose remained on the police force. In 1997, an attorney for the police union wrote a letter to the police commissioner complaining that Rose had been kept on administrative duty for two years and demanding his full reinstatement. Rose was then reinstated. Prosecutors today allege that he went on to molest five additional child victims, including some after Rose himself became union president from 2014 to 2017.

White House Labor Secretary Marty Walsh

In the May 14, 2021 print edition of The Wall Street Journal, the Editorial Board published “A Police Union Coverup in Boston.” The WSJ reported that The Boston Globe filed requests for the Internal Affairs file on Patrick Rose. The administration of then Boston Mayor Marty Walsh denied the request citing that the record could not be released in a way that would satisfy privacy concerns.

Imagine the outcry if the late Cardinal Bernard Law said this when The Boston Globe demanded a file on any foreknowledge of sexual abuse by Father Dominic Menna. It turned out in that case that there was no such file because the 80-year-old priest had never previously been accused. The Boston Globe repeatedly dragged the Archdiocese of Boston into court in 2002 to demand public release of scores of files on Catholic priests and never rested until every detail — corroborated or not — ended up in newsprint.

It is hard to imagine today that The Globe would simply settle for the excuse Mayor Marty Walsh provided. It is hard to imagine that the “Blue Wall of Silence” was any real obstacle for The Boston Globe which, perhaps to cover for its own inaction, reported that it was “astonishing [the] lengths to which the [Boston Police] Department and the now departed Walsh administration went to keep those files under wraps.”

The file remained “under wraps” until after Senate confirmation hearings that vetted Mayor Walsh and confirmed him (68 to 29) for a Biden Administration cabinet position as Secretary of Labor in 2021. Walsh signed a contract with the Boston Police Union in 2017 while Patrick Rose was still union president. It remains unclear what Marty Walsh knew and when he knew it.

A Massachusetts state supervisor of public records refuted the Mayor’s reasoning for keeping the file secret. He called upon (then) Mayor Walsh to provide a better reason for denying the Internal Affairs file on Patrick Rose. Walsh ignored this for two months until his mayoral successor, Kim Janey, released a redacted version of the file after the Senate confirmation hearing approved Mr. Walsh as Secretary of Labor. The Wall Street Journal reported:

“Mr. Biden picked Mr. Walsh because he is a union man. He was president of a Laborers’ Union local, as well as head of the Boston Building Trades, until he ran for mayor in 2013. As mayor, he showered unions with taxpayer money, including a contract with Mr. Rose’s police union in 2017 that resulted in a pay increase of 16-percent over four years. City employees in unions donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to his campaign. The Rose Coverup is relevant to Mr. Walsh’s duties at the Labor department.”

An Epilogue

Just as I was preparing to print and mail this post, someone sent me the July 2021 copy of Newsmax magazine containing an article by journalist Merisa Herman on this same story entitled, "Police Union Cover-Up Haunts Top Biden Official." [I chose my title long before seeing this]. Ms. Herman concluded:

“Rose had been given a pass from the media for what could be construed as a cover-up ... Someone in Congress might ask Mr. Walsh why Americans should believe he’ll fight union corruption when his city may have helped protect a union chief with a history of alleged predation against children.”

It is difficult to measure this story against what happened in 2010 to 80-year-old Father Dominic Menna whose life and priesthood were utterly obliterated by The Boston Globe spotlight for a half century-old claim that could never be corroborated.

It is difficult to measure this story against what happened to George Floyd in Minneapolis when a history of previous excessive force complaints in a police file were kept under wraps until someone paid with his life.

+ + +

Notes from Father Gordon MacRae:

Many thousands of readers have been circulating last week’s post, “Biden and the Bishops: Communion and the Care of a Soul.” Thousands in Washington, Chicago, New York and Boston have read that post. If you wish to send a printed copy to your bishop or anyone else, we have created a five-page pdf version that is printable.

We have also created a pdf with the name and address of every U.S. Catholic Bishop.

Learn more about The Boston Globe’ s Spotlight coverage of the Catholic Church and the Best Picture Academy Award for the film, Spotlight. You may never watch the Oscars again after reading “Oscar Hangover Special: Why ‘Spotlight’ Is a Terrible Film” by a courageous journalist, Joann Wypijewski, former Editor of The Nation. (It also sheds some much needed media light on my own travesty of justice.)

The Exile of Father Dominic Menna and Transparency at The Boston Globe

As Father Dominic Menna, a senior priest at Saint Mary’s in Quincy, MA, was sent into exile, The Boston Globe’s role in the story of Catholic Scandal grew more transparent.

“I’m a true Catholic, and I think what these priests are doing is disgusting!” One day a few weeks ago, that piece of wisdom repeated every thirty minutes or so on New England Cable News, an around-the-clock news channel broadcast from Boston. I wonder how many people the reporter approached in front of Saint Mary’s Church in Quincy, Massachusetts before someone provided just the right sound bite to lead the rabid spectacle that keeps 24-hour news channels afloat.

The priest this hapless “true Catholic” deemed so disgusting is Father F. Dominic Menna, an exemplary priest who has been devoting his senior years in service to the people of God at Saint Mary’s. At the age of 80, Father Menna has been accused of sexual abuse of a minor.

There is indeed something disgusting in this account, but it likely is not Father Menna himself. He has never been accused before. Some of the news stories have not even bothered to mention that the claim just surfacing now for the first time is alleged to have occurred in 1959. No, I did not transpose any numbers. The sole accusation that just destroyed this 80-year-old priest’s good name is that he abused someone fifty-one years ago when he was 29 years old.

Kelly Lynch, a spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Boston, announced that Father Menna was placed on administrative leave, barred from offering the Sacraments, and ordered to pack up and leave the rectory where he had been spending his senior years in the company of other priests. These steps, we are told, are designed to protect children lest this 80-year-old priest — if indeed guilty — suddenly decides to repeat his misconduct every half century or so.

Ms. Lynch declined to reveal any further details citing, “the privacy of those involved.” That assurance of privacy is for everyone except Father Menna, of course, whose now tainted name was blasted throughout the New England news media last month. Among the details Kelly Lynch declines to reveal is the amount of any settlement demand for the claim.

Some of the fair-minded people who see through stories like this one often compare them with the 1692 Salem witch trials which took place just across Massachusetts Bay from Father Menna’s Quincy parish. The comparison falls short, however. No one in 1692 Salem ever had to defend against a claim of having bewitched a child fifty-one years earlier.

Archdiocesan spokesperson Kelly Lynch cited “the integrity of the investigation” as a reason not to comment further to The Boston Globe. Does some magical means exist in Boston to fairly and definitively investigate a fifty-one year old claim of child abuse? Is there truly some means by which the Archdiocese could deem such a claim credible or not?

Ms. Lynch should have chosen a word other than “integrity” to describe the “investigation” of Father Menna. Integrity is the one thing no one will find anywhere in this account — except perhaps in Father Menna himself if, by some special grace, he has not utterly lost all trust in the people of God he has served for over fifty years.

Transparency at The Boston Globe

The June 3rd edition of The Boston Globe buried a story on page A12 about the results of an eight-year investigation into the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. Eight years ago, it was front page news all over the U.S. that the Los Angeles Archdiocese was being investigated for a conspiracy to cover-up sexual abuse claims against priests.

After eight years of investigation at taxpayer expense, California prosecutors reluctantly announced last month that they have found insufficient evidence to support the charges. That news story was so obviously buried in the back pages of The Boston Globe that the agenda could not be more transparent. The story of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church is front page news only when it accommodates the newspaper’s editorial bias. That much, at least, is clear.

But all transparency ends right there. The Globe article attributed the lack of evidence of a conspiracy by Catholic bishops to the investigation being “stymied by reluctant victims.” Now, that’s an interesting piece of news!