“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Shawshank Redemption and Its Grace Rebounding

Readers are struck by the fascination with this fictional prison from the mind and pen of Stephen King, while the real thing seems to resist any public concern.

Readers are struck by the fascination with this fictional prison from the mind and pen of Stephen King, while the real thing seems to resist any public concern.

July 2, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

The Shawshank Redemption was released in theatres just as I was led off to prison in September, 1994. Andy Dufresne and I went to prison in the same week, he at the fictional Shawshank State Prison set in Maine, and me one state over at the far more real New Hampshire State Prison in Concord.

In the years to follow its release, The Shawshank Redemption became one of American television’s great “Second Acts,” theatrical films that have endured far better on the small screen than they did in their first life at the cinema box office. The Shawshank Redemption is today one of the most replayed films in television history.

I’ve always been struck by the world’s fascination with this fictional prison that first emerged from the mind and pen of Stephen King. The real thing seems to resist most serious public concern.

Several years passed before I got to see The Shawshank Redemption. When I finally did, I could never forget that scene as new arrival, Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) stood naked in a shower, arms outstretched, to be unceremoniously doused with a delousing agent. It seemed the moment that human dignity was officially checked at the prison door.

The scene triggered a not-so-fond memory of my own arrival in prison coinciding with that of Andy Dufresne in September 1994. Andy Dufresne and I had a lot in common. We both came to that day of delousing with a life sentence, and no real hope of ever seeing freedom again. Upon arrival we both endured jeers from in-house consumers of the local news.

For my part, the rebuke was for my very public refusal to accept one of several proffered “plea deals.” This is about prison, however, and not justice or its absence, but the two are so inseparable in my imprisoned psyche that I cannot write without a mention of this elephant in my cell.

I refused a “plea deal,” proffered in writing, to serve no more than one to three years in exchange for a plea of guilty. Then I refused another, reduced to one-to-two years. I would have been released by 1997 had I taken that deal, but for reasons of my own, I could not. Even today, I could cut my sentence substantially if I would just go along with the required narrative, but alas … .

Andy and I also shared in common a misplaced hope that justice always works out in the end, and a nagging, never-relenting sense that we don’t quite fit in at the place to which it has sent us. This could never be home. Andy got out eventually, though I should not dwell too much on how. After thirty years, I am still here.

I was in my twenties when my fictitious crimes were alleged to have been committed. I was 41 when tried and sent to prison. For my audacity of hope for justice working, I was sentenced by the Honorable Arthur Brennan to consecutive terms more than 30 times the State’s proffered deal: a prison term with a total of 67 years for crimes that never actually took place. I am 72 at this writing and will be 108 when I next see freedom, if there is no other avenue to justice.

Dostoyevsky in Prison

As overtly tough as the Shawshank Prison appeared to movie viewers, Andy had one luxury for which I have always envied him. It was something unheard of in any New Hampshire prison. He had his own cell, and a modicum of solitude. Stephen King’s cinematic prison where Andy was a guest of the State of Maine was set in the 1950s and everyone within it had his own assigned cell.

Prison had changed a lot since then, even prisons in quaint New England landscapes where most other change is measured in small increments. In the decade before my 1994 delousing, prison in New Hampshire underwent a radical change. It was mostly due to the early 1980s passage of a knee-jerk New Hampshire law called “Truth in Sentencing.” Once passed, prisoners serving 66% of their sentence before being eligible for parole were now required to serve 100%. The new law was championed by a single New Hampshire legislator who then became chairperson of the state parole board.

Truth in Sentencing is another elephant roaming the New Hampshire cellblocks, and no snapshot of life in this prison can justly omit it. Truth in Sentencing changed the landscape of both time and space in prison. The wrongfully convicted, the thoroughly rehabilitated, the unrepentant sociopath all faced the same sentence structure: There is no way out.

In the years after its passage, medium security prison cells built for one prisoner were required to house two. Then a new medium security building called the Hancock Unit was constructed on the Concord prison grounds with cells built to house four prisoners each. A few years later, bunks were added and those four-man cells were now required to house six.

When I arrived in Hancock in early 1995, I carried my meager belongings up several flights of stairs, and then had to carry up my bunk as well. The four-man cells, having increased to six, were now to house eight. The look of resentment on my new cellmates’ faces was disheartening as I dragged a heavy steel bunk into their already crowded space.

Over the years I was moved from one eight-man cell to another, in each place adjusting to life with seven other strangers in a space meant for four. Generally, this was considered “temporary housing” for those who would move on to better living conditions after a year or two. I was there for 23 years, the price for maintaining my innocence.

I remember reading once about the great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Reflecting on his time in a Siberian prison, Dostoyevsky lamented, though I’m paraphrasing from memory:

"Above all else, I was entirely unprepared for the reality, the utter spiritual devastation, of day after day, for year upon year, of never, ever, ever, not for a single moment, being alone with myself."

Viewers of The Shawshank Redemption always react to the prison brutality depicted in the film. Some of that has always been present in the background of prison life, and there is no adjusting to it.

The most painful deprivation in any prison, however, is the absence of trust. That most basic foundation of human relating is crippled from the start in prison. But the longer term emotional toll is more subtle. The total absence of solitude and privacy is just as Dostoyevsky described it.

Imagine taking a long walk away from home, far beyond your comfort zone. Invite the first seven people you meet to come home with you. Now lock yourself in your bathroom with them, and come to terms with the fact that this is how you will be living for the unforeseen future.

In 2017, twenty-three years after my arrival in prison, I was finally able to move to a unit within the prison that housed two men per cell. It felt strange at first. Twenty-three years in the total absence of solitude had exacted a psychological toll. Just sitting on my bunk without seven other men in my field of view required some internal adjustment to adapt.

Then dozens of bunks were added to the dayrooms and recreation areas. Then space used for rehabilitation programs was converted to dormitories for the ever-growing overflow of prisoners. Confinement-sans-solitude crept like a virulent plague in the prodigious hills of New Hampshire.

Prison Dreams

There is, however, another perspective on this story about life in the absence of solitude. Also, like Andy Dufresne, I found friendship in prison, one that was the mirror image of Andy’s friendship with Red, portrayed in the film version of Stephen King’s story by the great Morgan Freeman. Friends and trust are both rare commodities in prison. But like shoots growing from cracks in the urban concrete, the human need for companions defeats all obstacles. Bonds of connection in this place happen on their own terms.

My friend, Pornchai Moontri had a very different prison experience from mine. He went to prison at age 18, in the State of Maine, and the very prison in which Stephen King’s story was set. In the years in which I was deprived of solitude in a small space with seven other men, Pornchai was a prisoner in the neighboring state where he spent most of those years in the utter cruelty of solitary confinement in a “supermax” prison.

Pornchai was brought to the United States from Thailand at the age of eleven, a victim of human trafficking. He became homeless in Bangor, Maine at age thirteen, and at 18 he was sent to prison. Pornchai is now 52 years old and he resides in his native Thailand, having spent well over 60% of his life in prison. This man once deemed unfit for the presence of other humans in Maine turned his life around with amazing results in New Hampshire.

Thrown together after my years in deprivation of solitude and Pornchai’s equal stint in solitary confinement, we lived with polar opposite prison anxieties. As the years passed in the 60 square feet in which we then dwelled, Pornchai graduated from high school, completed two post-secondary diplomas with highest honors, pursued dozens of programs in restorative justice, violence prevention, and mediation, and had a radical and celebrated Catholic conversion chronicled in the book Loved, Lost, Found by Felix Carroll (Marian Press 2013).

Pornchai Moontri then served as a mentor and tutor for other prisoners, wielding immense influence while helping to mend broken lives and misplaced dreams. The restoration of Pornchai has inspired others, and stands as a monument to the great tragedy of what is lost when strained budgets and overcrowding transform prison from a house of restorative justice into a warehouse of nothing more redemptive than mere punishment.

When Pornchai was twelve years old, a year before becoming a homeless teen in Bangor, Maine, he had a paper route. It is an ironic twist of fate that at just about the time Andy Dufresne and Red, sprang from the mind and pen of Stephen King, Pornchai was delivering the Bangor Daily News to his home.

Reflecting back on the reconstruction of his life against daunting obstacles, Pornchai once told me, “I woke up one day with a future, when up to now all I ever had was a past.” In the years to follow Pornchai’s transformation, he finally emerged from prison after 30 years to face deportation to Thailand, the place from which he had been taken at age 11. I wrote about this transformation, both for him and for me, in “Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom.”

Pornchai emerged from a plane in Bangkok, unshackled after a 24-hour flight to begin a life that he was starting over in what for him was as a stranger in a strange land. He handed his future over to Divine Mercy and now, five years after his arrival in Thailand, he is home, and he is free in nearly every sense of those words.

In The Shawshank Redemption, the innocent prisoner Andy Dusfresne escaped from his cage decades after entering it. He had written to his friend Red about the hopes of one day joining him in freedom. Red had no way to conceive that as even possible.

Like Morgan Freeman’s character, Red, I revel in the very thought of my friend’s freedom, even into the dense fog of a future we cannot see. We both dream of my joining him there in freedom one day. It’s only a dream, and by their very nature, dreams defy reality.

But I cannot help remembering those final words that Stephen King gave to Andy Dufresne’s friend, Red, as he finally emerged from Shawshank. We cling to those words as we cling to the preservation of life itself, while otherwise adrift on a tumultuous and never-ending sea:

I am so excited I can hardly hold the pen in my trembling hand. I think it is the excitement that only a free man can feel, a free man starting a long journey whose conclusion is uncertain.

I hope Andy is down there.

I hope I can make it across the border.

I hope to see my friend and shake his hand.

I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams.

I hope.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Authors generally prefer their own writing to any screenplay that transforms it into a movie. In an interview, Stephen King said that the film version of The Shawshank Redemption had the opposite effect: “The story had heart. The movie has more.” I have always been grateful to Mr. King for writing that story for Pornchai Max and I were unwitting characters within it, and our own character was somehow shaped by it. There is more to this story in the following posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

The Parable of the Prisoner by Michael Brandon

For Pornchai Moontri, A Miracle Unfolds in Thailand

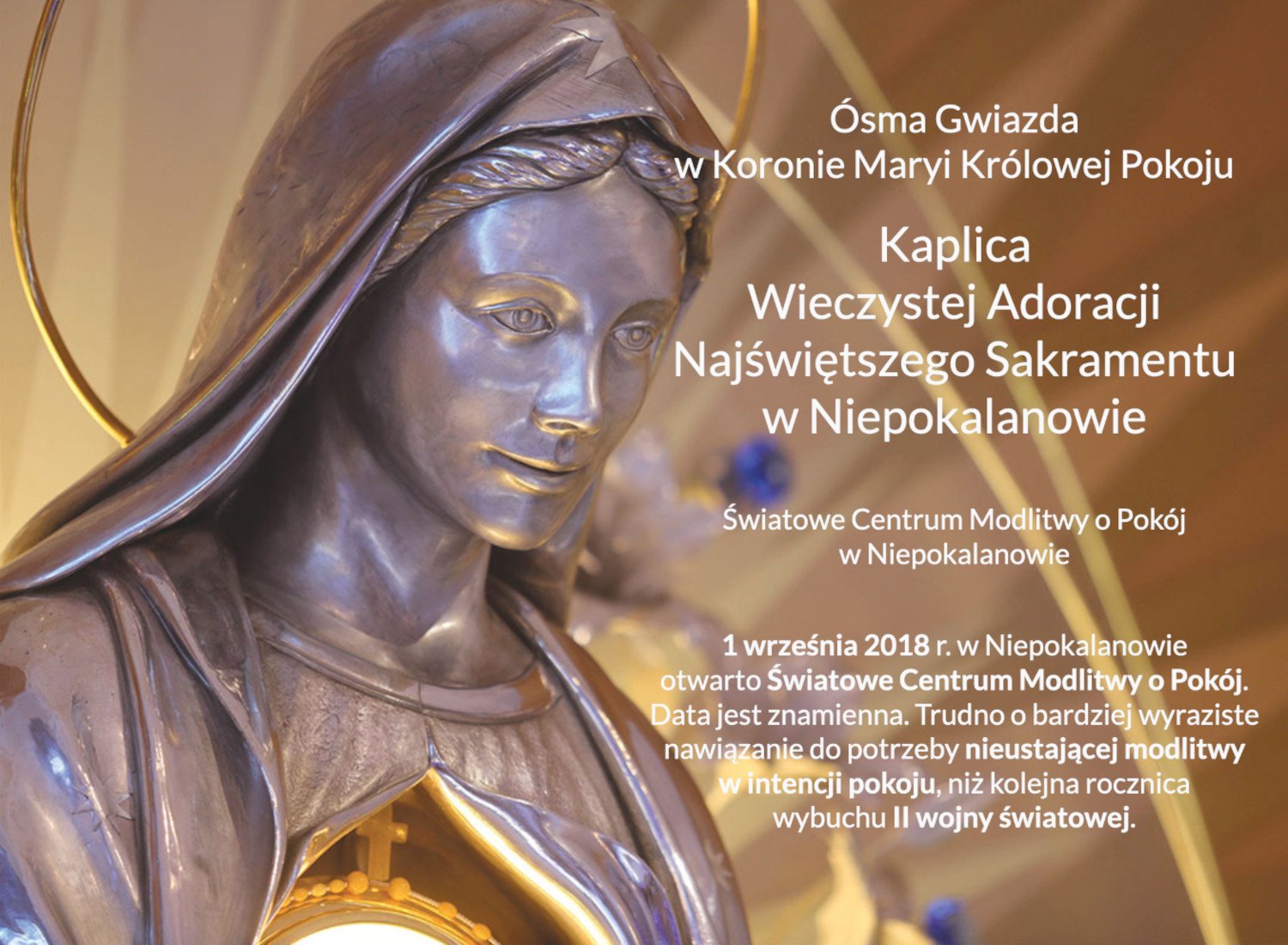

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Prison Journal: Jesus and Those People with Stones

For readers beyond these stone walls, stories from prison can be depressing. With an open heart some can also be inspiring, and inspiration is a necessity of hope.

For readers beyond these stone walls, stories from prison can be depressing. With an open heart some can also be inspiring, and inspiration is a necessity of hope.

March 30, 2022 by Father Gordon MacRae

Readers may recall the great prison film, The Shawshank Redemption starring Tim Robbins as wrongly convicted prisoner, Andy Dufresne, and his friend, Red, a role for which actor Morgan Freeman received an Academy Award nomination. The film was released in theatres on the same day I was sent to prison in 1994 so it was some time before I got to see it.

Readers of this site found many parallels between those two characters and the conditions of my imprisonment with my friend, Pornchai Moontri. For the film's anniversary of release, I wrote a review of it for Linkedin Pulse entitled, “The Shawshank Redemption and its Real World Revision.”

My review draws a parallel between the fictional prison that sprang from the mind of Stephen King and the prison in which I am writing this. One of the elements in my movie review was a surprising revelation. At the time Stephen King was writing The Shawshank Redemption, 12-year-old Pornchai Moontri, newly arrived from Thailand to America, had a job delivering the Bangor Daily News to his home.

One aspect of my review was about our respective first seven years in prison. I spent those years confined in a place that housed eight men per cell. I described the experience: “Imagine walking alone in an unknown city. Approach the first seven strangers you meet and invite them to come home with you. Now lock yourself in your bathroom with them and face the fact that this is what your life will be like for the unforeseen future.”

Pornchai spent those same seven years in prison in the neighboring state of Maine commencing at age 18. Those years for him were the polar opposite of what they were for me. He spent them in the cruel torment of solitary confinement. Years later, Pornchai was transferred to New Hampshire and I had been relocated to a saner, safer place with but two men per cell. We landed in the same place, but came to it with polar opposite prison anxieties: Pornchai had to recover from years of forced solitude while I was recovering from years of never, ever, ever being alone.

We survived together with a camaraderie that mirrored the one between Andy and Red that sprang from the mind of Stephen King. So you might understand why, in all the years of my unjust imprisonment, the year 2016 was personally one of the most difficult. After 11 years together in a cell in that saner place, Pornchai and I were caught up in a mass move against our will that sent us back to the dungeon-like place with eight men to a cell. We were told that it would be for only a few weeks. One year later, we were still there.

However, others suffered in that environment far more than we did. It was two years after we had engaged in the spiritual surrender of consecration “To Christ the King Through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.” We had inner tools for coping with loss and discomfort while others here had far less. Pornchai and I were well aware that many of the men with whom we had been living in that other, kinder place were also relocated. I was impressed to witness, in our first night there, Pornchai going from one eight-man cell to another to make sure our friends were safe and that the strangers now among them were civil. Pornchai had a knack for inspiring civility.

The Cast of This Prison Journal

After just three days there, one of the strangers assigned to our crowded cell with us decided he would ask to move because, as he put it to one of his friends, “Living with MacRae and Moontri was like living with my parents.” This was solely because I told him that he is not going to sell drugs out our cell window. His move came at just the right time. We were able to request that our friend, Chen, move to the now empty bunk in our cell. Speaking very little English, Chen had been thrown in with strangers. On the day I went to his cell to tell him to pack and come with us, it was as though he had been liberated from some other Stephen King horror story.

I live with an odd and often polarized mix of people. Among prisoners, about half become entirely engrossed in the affairs of this world, consuming news — especially bad news — with insatiable interest. The other half seem to live in various degrees of ignorant bliss about all that is going on in the world. They never watch news, read a newspaper, or discuss current events. They play Dungeons and Dragons, poker, and video games. While I was hunched over my typewriter typing “Beyond Ukraine” a few weeks ago, my current roommate had no idea anything at all was going on there.

Just as in the world, there are many evil things that happen in prison. People here cope with them by either blindly accepting evil as a part of the cost of living or they just never even acknowledge evil’s existence at all. These are not good options, nor are they good coping mechanisms. Acknowledging evil while also resisting it with all our might is the first line of defense in spiritual warfare. Many of the men in prison with me never actually embraced evil. They just didn’t see it coming.

Many readers have told me that they shed some tears while reading “Pornchai Moontri: A Night in Bangkok, a Year in Freedom.” Pornchai has often told me of how his appearances in these pages have changed his life. This was summed up in one sentence in his magnificent post: “I began to realize that nearly everyone I meet in Thailand in the coming days will already know about me.”

All the fears that Pornchai had built up for years over his deportation to Thailand 36 years after being taken from there just evaporated because of his presence in Beyond These Stone Walls. I once told him that he must now live like an open book. Exposing the truth of his life to the world could be freeing or binding. The truth of his life in this prison could be a horror story, a bad war movie, or an inspirational drama that people the world over could tune into each week, and what they will see would be entirely up to him. I do not have to tell you that his life became an inspiration for many, including many he left behind here. The evil that was once inflicted on him was gone, and only its traumatic echoes remain.

A few years ago, I began to write about some of the other people who populate this world. Some of their stories became very important, and not least to their subjects. Prisoners who had little hope suddenly responded to the notion that others will read about them, and what they read will be up to them. Some of these stories are beyond inspiring. They are the firsthand accounts of the existence of evil that once permeated their lives, and of actual grace when they chose to confront and resist that evil and turn from it. Their stories are the hard evidence of something Saint Paul wrote:

“Where sin increased, grace abounded all the more.”

— Romans 6:1.

Getting Stoned in Prison

My subtitle above does not mean what you might think it means. There is indeed an illicit drug problem in just about every prison, including this one. As long as there is money to be had, risks will be taken and human life will be placed in jeopardy. I recently read that the small state of New Hampshire has the nation’s highest rate of overdose deaths among people ages 15 to 50. This is driven largely by the influx of illegal drugs, especially lethal fentanyl.

But in the headline above, I mean something entirely different. The Gospel for Sunday Mass on April 3rd, the Sunday before Holy Week this year, is the story of the woman caught in adultery and her encounter with Jesus before a crowd standing in judgment and about to stone her (John 8:1-11). You already know that some prisoners are not guilty of the crimes attributed to them, but most are, and most of those have stood where that woman stood before Jesus. When prisoners serve their prison sentence, the judgment of the courts comes to an end, but the judgment of the rest of humanity can go on and on mercilessly.

It should not be this way. Our nation’s expensive, bloated, one-size-fits-all prison system leaves too many men and women beyond the margins of social acceptance. The first two readings this Sunday lend themselves to the mercy of deliverance from the past, not only for ourselves, but for others too.

“Thus says the Lord, who opens a way in the sea and a path through the muddy waters ... Remember not the events of the past; the things of long ago consider not. See, I am doing something new! Do you not perceive it? In the desert I make a way; in the wasteland rivers.”

— Isaiah 43:16-21

“Just one thing: Forgetting what lies behind, but straining forward to what lies ahead, I continue my pursuit toward the goal, the prize of God’s upward calling in Jesus Christ.”

— Philippians 3:14

When this blog had to transition from its older format to Beyond These Stone Walls in November 2020, we learned that most of our older posts still exist, but must be restored and reformatted. In our “Beyond These Stone Walls Public Library” is a Category entitled, “Prison Journal.” In coming weeks, we will restore and add there some of the posts I have written about the inspiring stories of other prisoners.

But before that happens, I want to add my voice to that of Jesus. Please read our stories armed with mercy and not with stones. That is the Gospel for this week’s Sunday Mass, and it is filled with surprises. We are restoring it so that you may enter Holy Week with hearts open. Please read and share:

“Casting the First Stone: What Jesus Wrote on the Ground”

+ + +

Two important invitations from Father Gordon MacRae:

Please join us Beyond These Stone Walls for a Holy Week retreat. The details are at our Special Events page.

Also, thank you for participating with us in the Consecration of Ukraine and Russia on March 25, the Solemnity of the Annunciation. We have given the beautifully written Act of Consecration a permanent home in our Library Category, “Behold Your Mother.”

+ + +

You may also like these relevant posts:

The Measure By Which You Measure: Prisoners of a Captive Past

Why You Must Never Give Up Hope for Another Human Being

Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom

After 29 years in a U.S. prison, adjusting to the world is an immense challenge. Simultaneously adjusting to another country and culture is a task beyond measure.

After 29 years in a U.S. prison, adjusting to the world is an immense challenge. Simultaneously adjusting to another country and culture is a task beyond measure.

A few years ago, I was invited to write a review of the now famous prison film, The Shawshank Redemption. It is the most replayed film in television history. I combined the review into a story about the prison I am in for going on 27 years. My account, published at LinkedIn, is “The Shawshank Redemption and its Real World Revision.” I hope you will read it.

There is a profoundly sad development in the film — which is a must-see, by the way. The elder prison inmate-librarian, a beloved character played by the great actor, James Whitmore, is paroled after serving many decades. The transition from life in prison to life as a free man in some unnamed Maine city is just too jarring. He is an alien in the strangest of worlds, the free one, and he is suddenly alone — isolated — for the first time in forty years. The alienation and isolation are just too much, and he takes his own life.

News of the character “Brooks”’ terrible end reaches the prison and casts a pall over an already darkened existence for the inmates of Shawshank. One of them — the wrongly convicted Andy Dufresne decides that he cannot have such an end. So he begins a plan for escape that will take 20 years to complete. He breaks through a cell wall and crawls through three miles of foul stench in a sewer pipe. Such an end is a sort of metaphor for leaving prison in the real world. You can free a man from decades in prison, but its residual stench can follow him for years to come.

America has a prison problem. This nation imprisons more of its citizens than all 28 countries of the European Union combined. The United States has five-percent of the world’s population but twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners. The only nations that impose more, and longer prison sentences are Third World countries.

Pornchai Moontri lost his freedom at age 18 on March 21, 1992. He was set free — after ICE tacked another five grueling months onto his sentence — on February 8, 2021, just weeks short of 29 years. He is now 47. The most formative and defining years of his adult life have been spent as a prisoner. And if you have followed the published account of his life, then you know that his prison began at age 11 when he was removed from Thailand. You will find that account, also published as a LinkedIn article, in “Human Trafficking: Thailand to America and a Cold Case in Guam.”

Just two weeks ago, I wrote the story of Pornchai’s five month post-prison stay in ICE detention and his return to Thailand. It ended rather abruptly because his final arrival was just hours before that post was published. Pornchai literally went from 29 years in shackles of one sort or another to standing in the lobby alone at the Bangkok Holiday Inn Express for his mandatory 15 days in quarantine required by the Thai government. We were notified at the last minute that we would have to arrange and prepay the hotel expenses. A few good friends and BTSW readers quickly mobilized to make short work of that obstacle.

The scene at the hotel check-in was both poignant and comical. On the day I write this, I was talking with Pornchai about the topic of this post, and he said, “Make sure you write about my first night in the hotel.” “All of it?,” I asked. “Don’t leave anything out,” he said. So here goes:

It was just after midnight on Monday into Tuesday Bangkok time, on February 9th. After a nearly 24-hour flight, and a brief appearance in the Bangkok Airport security area, the two ICE agents escorting Pornchai wished him well and left. Someone then escorted him to a waiting hotel van. Upon arrival, the driver let him out and said, “The check-in counter is just inside.” Pornchai was frozen in place and the driver looked puzzled. After a moment Pornchai said, “You mean ... I just go in by myself?” It had been 29 years since Pornchai entered a building unescorted.

Free in the City of Angels

In Thailand, Bangkok is called “Krung Thep,” meaning, “City of Angels.” It is a city that never sleeps, a city of 9.3 million souls. Imagine this scene. Pornchai was standing at the main entrance of an urban hotel with its dazzling lights, having to will himself to take the first step of freedom. He walked toward the light, through the doors, and into the brightly lit lobby. It was now about 1:00 AM, and even at that hour two smiling clerks awaited him behind a large counter. Pornchai had no luggage. He had nothing but the clothes he had worn during a grueling 24-hour flight.

“Sawasdee, Khun Pornchai,” said the clerk. Pornchai repeated from long dormant memory the traditional Thai greeting. The check-in went smoothly and he was given a keycard. He had no idea what it was for. Then the clerk said, your stay is in Room 3-8. The elevator is over there. Again, he was frozen in place. The clerk asked him a question in Thai and Pornchai answered with some embarrassment, “I’m sorry. I do not fully understand Thai.” The clerk then asked in English, “Is there anything more you need, Khun Pornchai?” He answered as he did the driver out on the street. “You mean ... I go by myself?”

Pornchai made it into the elevator. As the door closed, this was the moment when he first knew he was free. He stood still for a full thirty seconds wondering what to do. He had no living memory of ever being in an elevator in which he is the one to decide where it goes. Both exhilarated and intimidated, he pushed the “3” button and the elevator moved beneath his feet. When he arrived at Room 3-8, the door was locked. He had no idea how to get in. Then he remembered the keycard. “Maybe it’s this thing,” he thought. He put it in a slot upside down and nothing happened. So he tried again, and this time the door clicked open. He was utterly amazed.

Once inside the dark room, Pornchai began to feel along the walls for a light switch, but there wasn’t one. So he opened the door to let in some light. No light switch anywhere. Then he saw a slot near the door. “Maybe it’s this keycard,” he thought. So he inserted it and the lights came on. Then, finally, after 24 hours in flight and two more hours getting to this point, he had to use the toilet. I would usually spare you this, but he wants me to include it. He reached repeatedly behind him for a lever for the nicety of prison etiquette called “a courtesy flush.” It dawned on him that there was no one else anywhere nearby, another first for him.

But that did not solve the problem of flushing the toilet. After washing his hands he meticulously searched the room for anything that looked like it might flush the toilet. He found nothing. “Surely,” he thought, “the keycard doesn’t flush the toilet too!” So he went to get the keycard out of the wall, thus turning off the lights. Searching again in the dark, he could find no place on or near the toilet to plug in the keycard. But he refused to give up. He restored the lights and searched again. Finally, he spotted what looked like a logo on top of the tank. Do toilets have logos? It did not appear to have a button, but he had nothing to lose. So he reached out and touched the logo, and lo and behold, the thing finally flushed. Pornchai debated with himself whether he should tell me this story.

Pornchai took a quick shower, then collapsed in exhaustion on the bed. Both the room and the bed were larger than anyplace he had ever slept before, and the bed was far softer. He recalled his promise to me that he would not sleep in the bathtub. Thus began a fitful, anxious night, his first in freedom and his first in his homeland after an anguish-filled absence of 36 years. He had never before felt so alone.

Samsung to the Rescue

But we have friends in Bangkok, and they have long awaited Pornchai’s arrival. Yela Smit, a Bangkok travel agent, and Father John Le, a member of the Missionary Society of the Divine Word, dropped off some items for Pornchai that we had sent over there ahead of time. We purchased a small backpack and a change of clothes and pair of sandals often worn in Bangkok. We intended that Pornchai would carry this travel bag in flight, but every time we shipped it to him ICE would move him somewhere else just as it arrived. Then they would just ship it back to us. So we had it sent ahead of time to Yela to bring it to him. I also put together a box of items that would give him a sense of the familiar. This included some of his favorite books, a prayer book, the Saint Maximilian Rosary that BTSW reader Kathleen Riney made for him, and some of his treasured correspondence. Yela and Father John dropped these at the hotel as he slept.

They also brought him a new Samsung Galaxy smartphone loaded with an internet package. Yela sent me his number the day before, so by the end of his first full day in Thailand, we were able to speak. One of our Thailand contacts, Viktor Weyand, also connected with him on his first day there and every day since. Pornchai had never before touched, or even seen, a smart phone, but to my amazement it proved less of a challenge to him than the toilet. (Please don’t tell him I said that!)

A call from me was one of his first on the Samsung phone. I thought he might be elated to hear my voice, but he said, “Actually, I have been listening to you all afternoon.” He left me astonished when he said that he found his way into Beyond These Stone Walls and spent the whole day reading posts about himself, about me, and about some of our weird politics. He read the BTSW “About” page and spent two hours listening to the documentary interviews with me there. He was clearly a newborn fan of the world of information technology.

During my call the next day, I walked him through getting into the Gmail, Facebook, and LinkedIn accounts that our friends had set up for him over time. He was surprised to learn that he has over 600 Facebook “friends” most of whom are BTSW readers. Then came the real bombshell. I had him go to Bing.com and put his own name into the Search bar. The results were page after page of eye-popping affirmations of the good man he has become.

I asked him to do this search using Bing because I have found that Google, especially recently, seems to suppress some Catholic and other content with a conservative tone. I have never seen either Bing or Google, but before mentioning this to Pornchai I had a friend search his name on both. Clearly, the Bing search was fairer and more inclusive. Try it for yourself. Search "Pornchai Moontri" on both Bing and Google.

Pornchai had never before seen social media sites. Some of the followers of his Facebook page, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri, are men who had been in prison with him in both Maine and New Hampshire and are now free. All of them have struggled, but have been inspired by how Pornchai’s faith has inspired his journey and helped him face obstacles. One young man, John, was in Maine’s notorious “Supermax” solitary confinement prison with Pornchai 20 years ago. It did much damage to them both. John has written to me of how following Pornchai’s story has informed his own survival. Many others have said the same.

A Road with Many a Winding Turn

In the eleventh hour, just a week before Pornchai’s liberation from ICE and his flight to Thailand, the longer term plan we had for Pornchai’s housing diminished due to illness. Immediately, Father John Le, SVD, contacted me with an invitation for Pornchai to live with him and two other priests from his order in the city of Nontha Buri about one hour’s drive from the center of Bangkok.

Father Le’s principal ministry is the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees in Thailand. Father John is no stranger to the world of displaced persons. At age 15, he was one of the Vietnamese “Boat People” rescued at sea after fleeing a communist regime when American forces vacated Vietnam in the early 1970s. He made his way to Thailand and eventually became a Catholic priest. After twenty years of ministry in Papua New Guinea, his Order assigned him to Thailand six years ago.

In a recent phone conversation, Father John told me that he will soon drive Pornchai up to the northern city of Khon Kaen, an eight-hour drive, where Pornchai’s birth records are located. While there, they will obtain his official Thai citizen ID which he would have received at age 16 had he been in Thailand at that time.

From there, Father John said, they will spend a few days at his Order’s residence north of there where they manage a home and clinic for Thai children suffering from HIV. It is in the village of Nong Bua Lamphu.

This left me awestruck and speechless. It was in that very village that Pornchai lived as a young child with his extended family. He has shadowy memories of water buffalo and a rice paddy there. It was also from that very place that Pornchai was taken at age 11 setting in motion a long and traumatic odyssey from which he now returns full circle 36 years later.

For my part, my place in this amazing story is the most important thing I have ever done as a man and as a priest. The challenges ahead are many for me and for Pornchai, but I am left with no lingering doubt that the light of Divine Mercy has been a beacon of hope and trust for us both.

Sawasdee, my friends. Thank you for being here with us at this turning of the tide.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: I am most grateful to Yela Smit, Father John Le, and Viktor Weyand for helping to prepare a path for my friend’s long awaited journey home. On the day this is posted, Father John will pick up Pornchai from his required quarantine and they will drive together to Nontha Buri on the eastern side of the Bay of Bangkok. There, Pornchai will be a guest of Father John Le and two other priests from the Missionary Society of the Divine Word. Father John’s community struggles to meet its needs so I have pledged to assist by providing some modest room and board for Pornchai’s stay there. If you are inclined to assist as well, I explain how on our Special Events page.

You may also like these related posts referenced herein:

The Shawshank Redemption and its Real World Revision

Human Trafficking: Thailand to America and a Cold Case in Guam

Some of our friends nearby, who have helped to bring about Pornchai's transition, gathered for a Christmas prison visit last year. Here are left to right: Pornchai Moontri, Judith Freda of Maine, Samantha McLaughlin of Maine, Claire Dion of Maine, Viktor and Alice Weyand of Traverse City, Michigan, Father Gordon MacRae, and Mike Fazzino of Connecticut.

Please share this post!

From the Grip of Earthly Powers to the Gates of Hell

At the dawn of 2021, Covid-19 wreaks havoc in prison, Pornchai Moontri remains in unjust ICE detention, the free press and free world seem less so, and our politics exploded.

At the dawn of 2021, Covid-19 wreaks havoc in prison, Pornchai Moontri remains in unjust ICE detention, the free press and free world seem less so, and our politics exploded.

Many writers have expressed concern that this Christmas must have been especially painful for me given that it was my first in 15 years without my friend, Pornchai, present with me. I can only respond with the words of Red, Andy Dufresne’s friend in the great prison film, “The Shawshank Redemption,” “This empty place just seems all the more empty in his absence.”

But I am far more painfully troubled, not by Pornchai’s absence, but by the deeply unjust continuation of his imprisonment. I am not a person who tends to see all things in respect to myself.

A few years back, I was asked to write a review of Stephen King’s novella-turned-prison-classic (linked above). Its focus was on the highly unusual redemptive friendship between Andy and Red (portrayed in the film by Tim Robbins and the great Morgan Freeman). I reflected in the review that one day my own friend will depart from prison while I remain in its emptiness. Of that, I wrote, “Still, I revel in the very idea of my friend’s freedom.”

I stand solidly by that. I do revel in Pornchai’s freedom as it is very important to me. I worked long and hard to help bring it about. So the insult and injustice of Pornchai’s ongoing ICE detention months after his prison sentence has been fully served is as painful for me to bear as it is for Pornchai. I very much appreciate the selfless efforts made by Bill Donohue and others to call attention to this injustice (see our “Special Events” section) and we hope you will take part in this effort, but to date the hoped-for justice remains out of reach.

It was a central tenet of President Trump’s bold initiative for criminal justice reform — the First Step Act — that when a prison sentence is fully served and paid in full, it should not continue on in ways that are unjust such as unemployment, the denial of housing, or the restoration of a person’s freedom and good name. I respect and support President Trump in this. But now, after paying in full his debt to society, Pornchai is now entering a fifth month beyond his sentence in the worst prison conditions he has ever known. He is still an ICE detainee in a grossly overcrowded for-profit ICE facility in Jena, Louisiana.

The factors that contributed to this are a combination of Covid-19 (which has been more of an excuse, really), bureaucratic ineptness, greed and corruption, and no small dose of something that plagues too many public sector employees: abuses of power and a lack of transparency and accountability to the very public sector that pays the bills. That post must be written and it will be written. In the meantime, please support and pray for the rapid repatriation of Pornchai Moontri.

Our Crisis of Partisan Politics

One of the factors that made me feel the most bleak about the hopes for justice for either Pornchai or me came just after I wrote “Human Traffic: The ICE Deportation of Pornchai Moontri.” That was my first glimpse of the folly of hoping for justice in an election year. That post mentioned truthfully the pressure I had been receiving to present what was happening to Pornchai as President Trump’s fault. I pointed out with honesty and candor that this had nothing to do with Trump.

Pornchai was first ordered deported in 2007 during the last year of the administration of President George W. Bush. The State of Maine nonetheless felt it necessary to extract from Pornchai every day of the sentence imposed on him when he was 18 years old. He is now 47. That post went on to quote an article by the left-leaning Human Rights Defense Center which bestowed on President Barack Obama the title of “Deporter in Chief.” These are factual elements that were not contrived by me, but unless I became willing to publicly blame President Trump, there would be no help from anyone on the left.

That fact was driven home when I was contacted by a political activist in Pennsylvania who represented an endeavor to combat human trafficking. The person urged me to “take a giant step away” from helping Pornchai because “your name is already sullied in the public square” and “your posting on this cut the legs from democrats who might help him and you.” Needless to say, I did not take her up on the offer of “help.” It came with conditions reflecting a whole other layer of dishonesty.

I hope it is not lost on readers, on human rights activists, and, if he ever sees any of this, on the President himself, that I ask for no consideration at all for myself. What happened to Pornchai in America is a giant stain on America’s claim to be a mirror and champion of human rights for the the world. Thailand as a nation has been dragged before United Nations panels for the exploitation of children, but everything that happened to Pornchai happened in America, and now America only expels him.

As events of recent days made clear, there will be no political help for either me or Pornchai. It is not yet time for me to comment on everything that happened in Washington on January 6. The intransigence of all the players is still too heated for any comment of mine to do anything but erupt it again. Much more will be written of this, by me and others, but for now I just want to raise one point about the grave danger we are in as a society builds upon respectful human rights and civil liberties.

As a result of our political differences, Facebook and Twitter have permanently suspended the accounts of the current President and others of his mindset. Who will they come for next? What are we in for? As John Derbyshire wrote in a recent issue of Chronicles, “While low-level grumbling by persons of no importance may be tolerated, only opinions compliant with the state ideology will be allowed to air in the public forum.” This will be the most frightening outcome of the events of January 6, 2021.

A Catholic Parting of the Ways

Like so many people I know, as I look back over my investments of the last year, I come up feeling a little empty. I am not talking about financial investments for I don’t have any. I earn all of two dollars per day helping prisoners traverse the legal system. My “investments” refer to the places where I have invested my time, my energy, and most especially my mind and heart.

Being where I am, you might think that I am immune from the empty social media quest for “likes” and other signs of acceptability. It never sits well with me that my posts could be subjected to such artificial approval. I cannot even see Facebook or other social media, but I know without doubt that it blocks and distorts conservative political and religious viewpoints.

But social media is also where the world lives out its arena of civil discourse. It is not all evil, and some of it presents an under-utilized opportunity for evangelization. So, with the help of friends, I have a social media presence carefully presenting the Gospel in a minefield of otherwise twisted ideas. To garner some help in this effort, I have found dozens of faithful Catholic public and private Facebook groups that promote positive discourse about our faith. Many of these groups have welcomed me, and routinely post what I present.

Then I decided to risk digging a little deeper. I sought out a Facebook group for priests. My friends and I found only one, and it had several hundred members. So the first post I submitted was one I wrote in 2020 entitled, “Priesthood, the Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times.”

It was only hours before I found myself faced with one of the sins of the times: hypocrisy. A message came from the unnamed moderator of the priests’ group: “Given your situation, we do not think it is prudent for us to post anything you write.” Like so many untreated wounds, this one festered. It started off as anger, then humiliation, then hurt, then anger again.

This presented me with a full frontal experience of a phenomenon I have encountered in so many others. All the positive regard in the world cannot match the power of one unjust rejection from someone whom I would otherwise have respected. I have challenged penitents and counseling clients on this question for decades. Why does the negative so outweigh all the good that is said of some of us? Why do our psyches empower the negative?

There are lots of answers to this almost universal phenomenon, but they are too many for a single blog post. One of the answers, and perhaps the most important one, is a long neglected New Year’s resolution to identify where my treasure lies. This inquiry comes from a single, haunting line in the Gospel: “Wherever your treasure lies, there will your heart be also.” (Matthew 6:21 & Luke 12:34) Saint Luke especially framed this in a way that requires insight:

“He began to say to his disciples, ‘Beware the leaven of the Pharisees, which is hypocrisy. Nothing is covered up that will not be revealed, or hidden that will not be known. Whatever you have said in the dark shall be heard in the light, and what you have whispered in private rooms shall be proclaimed upon the rooftops.’”

That is what I walk away with in this story. My only response to the priest who passed such harsh judgment on me is to never be that priest. My only response to the priest who walks by the man left for dead in the famous parable (Luke 10:25-31) is to never be that priest.

Which brings me back to my friend, Pornchai Moontri. Catholicism in America is a vast apostolic network of faith in action. I am so very proud of all of you who have sent in Bill Donohue’s Petition to the White House on our “Special Events” page. And I am immensely proud of Bill Donohue for taking this up. The response from our ranks should be thunderous. If the leaven of the Pharisees is hypocrisy, then the leaven of the righteous is faith found in selfless action.

The Trials of a Year in a Global Pandemic

All of the trials of 2020 in prison were lived in the shadows of the global pandemic of Covid-19. Amazingly, as prison systems across America became giant super transmitters of the coronavirus, this one managed most of the year with but a single case among prisoners and only a manageable handful among prison staff. The price for such an almost Amish removal from the mainstream was costly. Prisoners here have had to surrender all contacts with loved ones as the facility embraced a massive lockdown last March.

All visits, chapel activities, volunteer programs, most education, and virtually anything from outside these walls was curtailed. The limits on our lives became more severe as the year progressed. Since September, starting just at the time Pornchai Moontri was taken away on September 8, we have been in a state of near-total lockdown and isolation. Even this could not halt the virus from spreading. In just the last few months, even with all the lockdown measures, 81 prison staff and hundreds of prisoners here have contracted the virus. Due to contact tracing, the numbers placed in quarantine have been vastly greater.

Present1y, I live in the only housing unit that is not yet fully engulfed in quarantine. Currently eight of the twelve units here are fully locked down in quarantine. Presently, three dormitories, the weight room and the gymnasium have all been cleared out to make room for quarantine bunks. The wave of fear that has moved through the prison seems worse than the wave of Covid cases. Presently, I cannot leave my cell without a mask.

The State of Louisiana, where Pornchai has been held unjustly for over four months awaiting transport, has the fourth highest rate of Covid infection in the country. Detainees by the hundreds from Central America, with just a few Asians mixed in among them, are housed 70 to a room with no testing, little screening, and no obvious preventive measures. America, on either side of the aisle, does not seem to have the political will to address this.

Those from Central American countries seem to be moved out in large numbers while Pornchai and other Asian detainees are kept in horrible conditions for much longer. I plan to write in much more depth about ICE in an upcoming post.

Until then, I can only say thank you for being here with us throughout the trials of the past year. Your prayers and your support and friendship have been priceless, and have made a very great difference. I especially thank Bill Donohue for the courage and sense of justice the Catholic League has stood for. If you are not yet a member, please join me in that important cause at www.CatholicLeague.org

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae:

Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You may also like the related posts referenced herein:

Human Traffic: The ICE Deportation of Pornchai Moontri

Priesthood, the Signs of the Times and the Sins of the Times

And BTSW has a Library! Unlike most blogs, our past and present posts are slowly being organized by topic in 28 categories of special interest. This is a work in progress, but check it out, and come back for updates.