“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Weapons of Mass Destruction

At the behest of paid, unnamed ‘trauma-informed consultants,’ my diocese provided a six-figure settlement of a claim far too old to be filed in any court of law.

At the behest of paid, unnamed ‘trauma-informed consultants,’ my diocese provided a six-figure settlement for a claim far too old to be filed in any court of law.

May 22, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

And they keep on coming. A year before the 2002 wave of clergy sex abuse claims rippled out of Boston across the country, Sean Murphy, age 37, and his mother, Sylvia, demanded $850,000 from the Archdiocese of Boston. Sean claimed that three decades earlier, he and his brother were repeatedly molested by their parish priest. In support of the claim, Mrs. Murphy produced old school records placing her sons in a community where the priest was once assigned. No other corroboration was needed. Shortly thereafter, Byron Worth, age 41, recounted molestation by the same priest and demanded his own six-figure settlement. The men were following an established practice of “mediated settlements,” a precedent set in the early 1990s when a multitude of molestation claims from the 1960s and 1970s emerged against Father James Porter and a few other priests. In 1993, the Diocese of Fall River settled some 80 such claims in a single negotiated deal. Other Church institutions followed that lead on the advice of insurers and attorneys.

Before the Murphys’ $850,000 demand was paid, however, Sean, his mother, and Byron Worth were indicted by a Massachusetts grand jury for conspiracy, attempted larceny, and soliciting others to commit larceny. It turned out that Sean and Byron were once inmates together at the Massachusetts Correctional Institute at Shirley where they concocted their fraudulent plan to score a windfall from their beleaguered Church.

On November 16, 2001, Sean Murphy and Byron Worth pleaded guilty to fraud charges and were sentenced to less than two years in prison for the scam. The younger Murphy brother was never charged, and Mrs. Murphy died before facing court proceedings. Local newspapers relegated the Murphy scam to the far back pages while headlines screamed about the emerging multitude of decades-old claims of abuse by priests. When two other inmates at MCI-Shirley accused another priest in 2001, a Boston lawyer wrote that it is no coincidence these men shared the same prison. “They also shared the same contingency lawyer,” he wrote. “I have some contacts in the prison system, having been an attorney for some time, and it has been made known to me that this is a current and popular scam.”

It is not difficult to understand the roots of such fraud. Prison inmates, like others, read newspapers. Just months before the onslaught of claims against priests, the Archdiocese of Boston landed on the litigation radar screen with the notorious arrest of Mr. Christopher Reardon, a young, married, Catholic layman, model citizen, and youth counselor at a local YMCA who was also employed part-time at a small, remote parish outpost north of Boston. As Mr. Reardon’s extensive serial child molestation case came to light—with substantial and graphic DNA, videotape, and photographic evidence of assaults that occurred over previous months—the YMCA quickly entered into settlements consistent with the State’s charitable immunity laws.

In a search for deeper pockets, however, a local contingency lawyer pondered for the news media about whether the rural part-time parish worker’s activities were personally known—and covered up—by the Cardinal Archbishop of Boston. It was a ludicrous suggestion, but it was a springboard to announce in the Boston Globe (July 14, 2001) that “the hearsay and speculation” among lawyers and clients, is that “the Catholic Church settled their cases [of suspected abuse by priests] for an average of $500,000 each since the 1990s.”

It was a dangled lure that would soon have many takers, some of whom have been to the Church’s ATM more than once. In January of 2003, at the height of the clergy scandal, a 68-year-old Massachusetts priest had the poor judgment to be drawn into a series of suggestive Internet exchanges with a total stranger, a 32-year-old man named Dominic Martin. Using a threat of media exposure of the printed exchanges, Mr. Martin demanded that the priest leave an envelope containing $3,000 in a local restaurant lobby.

The frightened priest, who never had a prior accusation, compounded his poor judgment by paying the demand. Soon after, another cash demand was made, but the priest finally called the police who set up a sting of their own. On January 24, 2003, Dominic Martin and his wife, Brianna, were arrested at the drop point, and charged with extortion.

The police report revealed that Mr. Martin had changed his name. His birth name was identified as Tod Biltcliffe, a man who, a decade earlier, obtained a settlement when he accused a New Hampshire priest of molesting him in the 1980s. At the time the priest protested that Mr. Biltcliffe was committing fraud and larceny. The Church settled anyway. Biltcliffe’s claim was that when he was 15 years old, the priest fondled his genitals while the two were in a hot tub at a local YMCA. Curiously, the investigation file contained a transcript of a 1988 “Geraldo Rivera” show entitled “The Church’s Sexual Watergate.” One of the cases profiled was that of a young man who claimed that a priest fondled his genitals while the two were in a hot tub at a local YMCA.

The 1988 “Geraldo” transcript was a sensationalized account of clergy sex abuse cases from the 1970s and 1980s. The transcript is notable because it contains many of the same claims of exposing secret Church documents, archives, and episcopal cover-ups in 1988 that lawyers and reporters claim to have exposed for the first time in 2003.

Writer Jason Berry, and contingency lawyers Jeffrey Anderson and Roland Lewis all appeared live on “Geraldo” on November 14, 1988 to announce the existence of secret Church archives, cover-ups by bishops, and out-of-court settlements of Catholic clergy sex abuse claims across the country. Jason Berry, who excoriates the Church and priesthood at every turn, actually defended, in 1988, the existence of so-called “secret” Church archives: “Canon law says that you have to have a secret archive in every diocese…. That’s funny because I’ve been attacking the Church for three years on this… I want to express my own irony of [now] being in a position of defending the Church.”

Enter Shamont Lyle Sapp

When Shamont Lyle Sapp first detected the smell of money, he found it too enticing to pass up. Convicted for a series of bank robberies, Mr. Sapp, then age 51, was serving a lengthy sentence in the dark peripheries of the U.S. Penitentiary in Allenwood, Pennsylvania when the scent first drifted by his cell in 2008. That was when Sapp filed a lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Portland, Oregon. Detailing his tragic past, Sapp’s lawsuit claimed that he was a stranded teenage runaway from his Pennsylvania home en route to stay with relatives in Oregon. Then Archdiocese of Portland priest, Father Thomas Laughlin took advantage of his plight to repeatedly sexually abuse him.

Sapp claimed in his highly detailed lawsuit that the priest offered the young runaway a job cutting grass, then sexually abused him at a Portland Catholic church. Then Father Laughlin sodomized him during a five-day motel stay paid for by the priest who then funded the youth’s return trip to Pennsylvania. It was the latest horror story in the Catholic abuse narrative, and one that dismayed Catholics coast to coast.

Mr. Sapp’s story rang true, so it flew. Further inquiry was deemed unnecessary. The detailed claims were reported to civil legal authorities for whom the story also rang true, but Father Tom Laughlin had already been accused and convicted by others with similar tales. Mr. Sapp’s disturbing story added to the weight of a growing millstone around the priest’s neck.

In all public documents in the case, Mr. Sapp found refuge among an ever-expanding list of “John Does” accusing priests from the Archdiocese of Portland to cash in on its bankruptcy proceedings. Sapp’s story was accepted at face value resulting in a cash settlement of $70,000. Inmate Sapp accepted the offer while lawyers, the Archdiocese, and victim advocates all pontificated about how no amount of money could compensate him for the trauma he endured. As for Father Laughlin, the “credible” (aka “settled”) accusations drove another nail into the coffin containing the remains of his priesthood as the Archdiocese sought his dismissal.

There was only one problem with Shamont Lyle Sapp’s story: “It was entirely fabricated,” said Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen Peifer who in 2014 prosecuted Sapp for mail fraud and other federal charges for this and three similar frauds carried out against Catholic priests and dioceses in four jurisdictions. While serving another sentence in a medium security state prison in Minersville, PA, Mr. Sapp filed a second lawsuit claiming that a priest of the Diocese of Tucson, Arizona sexually abused him.

Later still, Sapp was serving a sentence in a South Carolina prison from where he sought compensation for claimed sexual abuse by another priest. And before all the above, Sapp filed a 2006 lawsuit claiming that a Spokane, Washington priest had sexually abused him in a similar account.

In all these other claims, Sapp picked from diocesan records the names of senior priests who had never before been accused, destroying not only their good names, but their vocations. Each was removed from ministry under the terms of the U.S. Bishops’ Dallas Charter. They became “Priests in Limbo,” as the National Catholic Register’s Joan Frawley Desmond described priests living, sometimes for years, under a cloud of shame and suspicion for events that could not be disproven after the passage of time. In each of his claims, Shamont Lyle Sapp simply did a little research on publicly available bankruptcy proceedings entered into by each of the four beleaguered dioceses he sued. He then attached his name and claims to each case — one by one over several years — aided and abetted by an assurance of anonymity as “John Doe” at every level in the settlement process.

He was also “John Doe” in the news media, and in the fired-up rhetoric of the activists of SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests who are ready to dismiss any hard questions as “revictimizing the victims.” It was ultimately his own greed that unfolded Mr. Sapp’s hand. In 2011, Sapp gained some notoriety when he filed a lawsuit seeking $1 million in damages against comedians Jamie Fox and Tyler Perry, falsely claiming that they stole from him an idea for a film project called “Skank Robbers.” Finally, someone took a hard look at Shamont Lyle Sapp, and it was his undoing.

“Like the Anti-Communist Witch Hunt of the 1950s”

In a 2004 article in the Boston Phoenix, “Fleecing the Shepherds,” legal expert and author Harvey Silverglate cautioned against capitulating to significant numbers of questionable claims brought after the Church entered into huge blanket settlements. In some cases, such claims were deemed “credible” — the standard established for permanent removal of accused priests — with no other basis than their having been settled.

As accusations swept over the U.S. Church, few in the media dared write anything contrary to the tidal wave gaining indiscriminate momentum against the Church. A notable exception was the left-leaning Catholic magazine Commonweal, which editorialized: “Admittedly, perspective is hard to come by in the midst of a media barrage that is reminiscent of the day care sex abuse stories, now largely disproved, of the early nineties… All analogies limp, but it is hard not to be reminded of the din of accusation and conspiracy-mongering that characterized the anti-Communist witch hunts of the early 1950s.”

With media coverage of the unprecedented $4 billion invested in mediated settlements, the trolling for claims and litigation continues unabated. In 2007, a Boston area high school history teacher and coach of twenty years, a husband and father with no prior record or accusation, was caught up in an Internet sting by New Hampshire Detective James F. McLaughlin posing on-line as a teenage boy cruising Internet chat rooms for sexual encounters. The practice has netted the detective some 600 arrests, including — by his own estimation — one Catholic priest, six police officers, and 18 public school teachers.

The Keene, New Hampshire police detective was also known to have fielded cases for local contingency lawyers. The ex-teacher, now prison inmate, related that as the handcuffs were set upon him, before he was even led out of the YMCA to which he had been lured and arrested, Detective James F. McLaughlin reportedly asked some enticing questions: “Are you a Catholic?” “Yes,” said the suspect. “Were you ever an altar boy?” Another “Yes.” “Were you ever molested by a priest?”

+ + +

Note from Fr Gordon MacRae: The mainstream media, and sometimes even the Catholic media as well, too often shrinks from reporting on the story of fraudulent claims of victimhood. So please share this post on social media and elsewhere. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

The Lying, Scheming Altar Boy on the Cover of Newsweek

Follow the Money: Another Sinister Sex Abuse Grand Jury Report

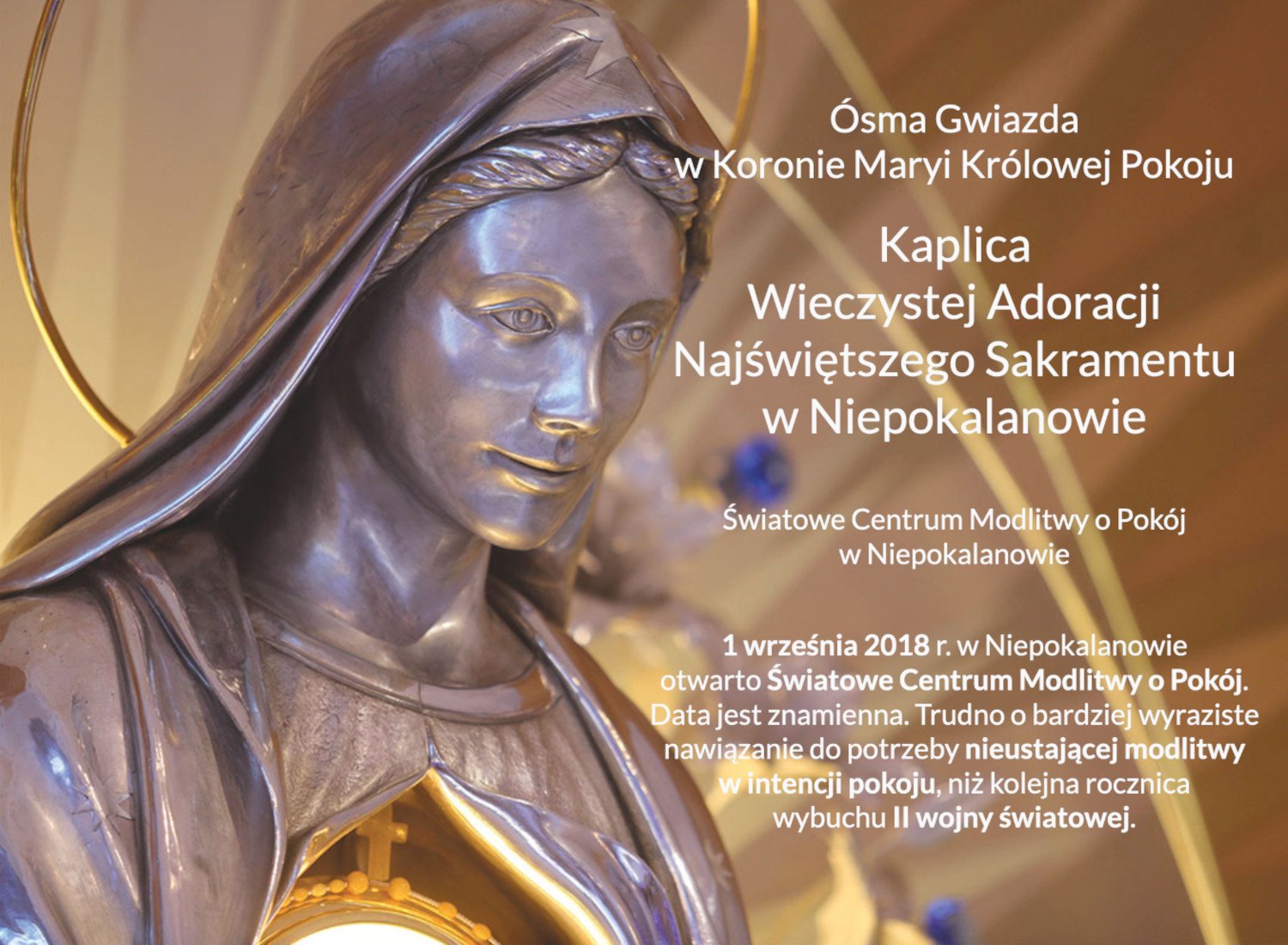

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Bishops, Priests and Weapons of Mass Destruction

Pope Francis promulgated Vos estis, a law applicable to bishops. Previously, if a bishop was accused of a canonical offense, only the Pope could bring him to task.

Pope Francis promulgated Vos estis, a law applicable to bishops. Previously, if a bishop was accused of a canonical offense, only the Pope could bring him to task.

Recently, behind the scenes at Beyond These Stone Walls, people have been working to restore and update Father Gordon MacRae’s older posts and save them in multiple categories in the Library at BTSW. One of the categories is Catholic Priesthood where this post, I expect, will find its permanent home. One such article was “Goodbye, Good Priest!” It was an updated reflection on the story of Father John Corapi, posted anew without any notice or fanfare. Nonetheless, it received more than 6,000 visits and 3,700 shares on social media in the first 24 hours after it was posted. This happened even before Fr John Zuhlsdorf — the famous Fr Z — posted a link to another blog informing readers that Fr Corapi, thanks be to God, had reconciled with his religious order several years ago and has been living a quiet life of prayer in one of its community houses. Fr Z’s post was “If you do not forgive men their trespasses neither will your Father forgive your trespasses.”

We had not heard about Fr Corapi for many years. His, we thought, was one of the many forgotten tales about priests, guilty, or even merely accused, of horrendous sins, whose cases often were treated with little regard for human, civil or canonical rights or due process. Fr Gordon and I were commenting that, being reminded of Fr Corapi, we realize that we have not progressed very far in the last twenty years. What Fr Gordon and I see now is that Father Corapi’s case was a small seed planted in our collective psyche that has germinated, now affecting all priests.

When the sexual abuse scandal exploded in the American press in 2002, many bishops were faced with the reality that their predecessors had known about sexual abuse of minors by priests and handled it in a way that was seen as pastoral at the time but which failed to meet today’s expectations. Back then, accused priests were shuffled off for psychological treatment, reassigned on the advice of the medical professionals to new parishes for a fresh start; sometimes they reoffended, or quietly retired to live in peace with their consciences. Even though the Vatican quietly had promulgated new laws in 2001 to deal with the crime of sexual abuse of a minor among some other of the more serious offenses in the Church, in the wake of the Boston Globe’s 2002 exposé, bishops threw up their hands and said to the Vatican, “My predecessor did this; you have to help me get out of this mess!”

And so dawned the era of the Dallas Charter. In the face of unrelenting public pressure and criticism, the Church, beginning in the United States but soon almost everywhere, began to treat allegations as proven crimes, to treat priests like chattel, to put money over preaching the Gospel. The Dallas Charter ushered in an era that means one strike and you’re out, and, in fact you don’t even have to prove that it was a strike: credibly accused quickly became the operative expression. In effect, the first decade of the 21st century witnessed the Church take on the notion that the priesthood was more disposable than it ever had been before. It was a reaction of fear.

Soon after, file upon file was sent to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) as bishops scoured their personnel files for any priest previously accused of sexual abuse. Even though the case had been dealt with already, according to the pastoral plan mentioned above, current bishops were looking for Rome to revisit the case and, it was expected, remove the priest permanently from ministry if not the clerical state itself. The caseload became so heavy that the CDF had to notify bishops that a deadline was being set after which no historical cases could be submitted. Apparently, someone had forgotten to inform everyone involved that law, especially penal law, cannot, in justice, be applied retroactively.

So far, we have only been talking about accusation of sexual abuse of minors. Fr John Corapi was never accused of that. He was accused of sexual misconduct, perhaps even concubinage, with an adult woman among supected financial misdeeds. In the heat of the abuse scandal, his case was being treated as if the Dallas Charter applied, which it did not. Father Corapi realized that he would never be treated according to the canon law of the Church. He knew he was considered guilty; nothing was going to change that, so he walked away. It is a sad commentary on the Church that such a gifted man was driven to near despair, that Church officials could be so indifferent to basic tenets of justice and due process. But that’s where we were.

Jump forward several years. In 2019, Pope Francis promulgated Vos estis, a set of laws applicable to bishops. Prior to those laws, bishops were directly responsible to the Pope alone. If a bishop was accused of a crime, like sexual abuse of a minor, only the Pope could bring him to task. Canon law assumes that people with authority in the Church, like bishops, are not saints, but at least God-fearing men seeking virtue. In fact, canon law only really works when that’s the case. People like Theodore McCarrick, the former Cardinal and Archbishop, got away with his misconduct for so long because a lot of bishops are not God-fearing men. McCarrick was relieved of his clerical obligations in 2019 and is now a layman.

With everything the Pope has to do, he certainly does not have time to micro-manage the lives of 5,000 bishops. The problem, becoming apparent, was that not only priests were being accused. The ravenous press and hysterical crowd were not satisfied. Bishops were next on the hit list. Hence, Pope Francis set up a system whereby bishops are now accountable for their own misconduct, even historical accusations from when they were yet priests. They are accountable, as well, for how they handle, as bishops, accusations of sexual abuse of minors by priests subject to them. With Pope Francis’ new legislation, the Congregation for Bishops is authorized to investigate accusations made about bishops in much the same way that the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was authorized in 2001 to do the same regarding priests. This is new territory and bishops are clearly anxious.

Guilty Merely for Being Accused?

Since the promulgation of Vos estis, several bishops have been removed from office or disciplined in some way: Bishop Richard Malone, emeritus of Buffalo; Bishop Michael Bransfield, emeritus of Wheeling-Charleston; Archbishop Henryk Gulbinowicz, emeritus of Wroclaw, Poland; Bishop Michael Hoeppner, emeritus of Crookston to name just a few. It’s a new world out there since 2019. What bishops have done to priests since 2002 is now being done to them.

“ The measure with which you measure will be measured out to you.”

Pope Francis, in Vos estis, expressed his wish that bishops conferences set up confidential reporting mechanisms such that people who know of misconduct committed by a bishop could safely report it knowing that action would be taken to investigate. The Canadian bishops conference announced a few weeks ago just such a mechanism. Anyone can now call a confidential line, or submit an online report, to a third-party agency which will receive the information and, in turn, pass on a report to the appropriate bishop. That bishop, in receipt of the report, will consult the Congregation for Bishops on how to proceed. Whatever else it is, and it is many things, this move is a lot of virtue signaling. Nothing guarantees that the report will be taken seriously. The only certainty is that a secular third party is being paid to receive and pass on information.

There is no real transparency to the procedures that are used to investigate a bishop — and I’m not arguing there should be, in this or any investigation of a priest — it is not evident that such things belong to the realm of public knowledge. Instead, we must trust that what is being done is just and legal — there’s no sense having a code of law in the Church if it means nothing or is not going to be used. Unfortunately, the Church’s track record in this regard leaves us with very little trust. With these new initiatives, nothing says that the bishop reporting to Rome about his brother bishop will not convince the Vatican that the allegation is unfounded or exaggerated. And, to be fair, understand that the Vatican has to trust the bishop consulting them. If they can’t, how is the Vatican to know and what is it supposed to do? We’re back to the headline: “Needed: God-fearing men trying to live lives of virtue.”

Now that bishops are being held to the same standards, or lack thereof, they have become hypervigilant of their priests, or, rather, of their own reputations. Virtue signaling abounds: bishops are tough on clerical misconduct. Now, not only accusation of sexual abuse of a minor leads a bishop to remove a priest from ministry, but, indeed, any misconduct whatsoever. That was the seed planted by Father Corapi’s case. Anything done by a priest that is going to cause publicity, or a lawsuit, is now treated in the same way as an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor. A priest is put on so-called administrative leave, his faculties are removed, he is not allowed to perform any priestly ministry except the celebration of Mass in private, which means alone.

This is all done, they say, just like they did in the early 2000’s, pro bono ecclesiae — for the good of the Church. This is being done by bending the law to the point of breaking. What priest, especially if he is guilty of something, is going to challenge his bishop’s abuse of the law. Priests who have been accused of misconduct, not involving minors, are now being removed from ministry under the guise that they are not suitable for assignment because of their misconduct, even though that misconduct may have been adjudicated and punished already — justly or not is another question. Bishops go so far as to encourage the priest to petition for laicization. The bishop can’t force a priest out of the priesthood because whatever he is alleged to have done doesn’t warrant such a punishment. But the bishop doesn’t want to be responsible for the ‘unassignable’ priest for the rest of his life, nor does he want to continue paying the priest.

Check any “Policy for Cases of Misconduct” published by a diocese. Many of them have clauses that say a priest found guilty of misconduct will never minister in the diocese again. Of course, such clauses are not allowed by canon law. No one questions what procedures will be used to determine the guilt or innocence of the accused priest. But what looks good is the policy itself. The Church has gone tough, not just on abusing minors, but on any misdeed. Try to find a definition of misconduct, or a list of behaviors that is classified as misconduct — you won’t. Vague is good: it allows those in authority to cite the law while interpreting it as they wish. Those are the parameters we are operating within today.

Fear and panic, there’s the problem. Instead of turning to Christ, we look to the world for our sense of self-worth as a Church. Are we held to impossible standards by the world? Yes. Does the world despise us because the Gospel preaches something counter-cultural? Yes. Are they going to sue us for every penny we own? Probably. Jesus told us, “If the world hates you, be aware that it hated me before it hated you” (John 15:18). The Church certainly has made mistakes in the last half-century or more. One of the biggest ones was turning a blind eye to immorality, especially sexual immorality among clergy and the faithful. In its zeal to be pastoral as a way of opening up to the world — a mantra of Vatican II — she failed to enforce her laws, or use her laws to bring justice and transparency to cases of crime and misconduct. The way out of this mess is not more laws, not more father turning on son and brother on brother tactics reminiscent of Nazi Germany. The answer is to read and heed the Gospel.

“For They Do Not Practice What They Preach” (Matthew 23:3)

In July 2013, Pope Francis was questioned about a Monsignor whom the Holy Father had appointed to a Vatican office. The Monsignor, according to reports, engaged in homosexual activity several times. The press wanted to know from the Pope how this person could be assigned given his past. Pope Francis came out with his now infamous line, “If someone is gay and he searches for the Lord and has good will, who am I to judge?” The press, to this day, wildly misinterprets what the Holy Father said, namely, that someone who was seeking the Lord with good will, i.e., repenting of past sin and seeking the right path, ought not to be judged by us. The rationale behind that is nothing other than the whole Christian message: Christ died so that all of us sinners could be redeemed. The Pope was saying, in essence, that someone could be a very sinful person, but repentance is always possible. Furthermore, he was pointing out that someone’s sinful past does not necessarily disqualify one from working in the Church — to be sure, sometimes it does, but not always. How would any of the apostles survive as priests or bishops in today’s climate?

In our Lord’s day, the religious leaders were worried about the popularity of Jesus. They didn’t want the people, the mob, to turn against them. In the end, it was they who, in the midst of the mob, told Pilate that they had no King but Caesar. It was they who instigated the mob’s choice of Barabbas over Jesus. The mob can be a frightening place when we have lost sight of Heaven. Jesus Himself was confronted with a mob. When they brought to Him the woman caught in adultery, the mob was after Him, not so much the woman who had been caught flagrantly in sin. They wanted to trip Him up about the law. Jesus was uncowed by their bullying. He didn’t lash out at the mob; rather, he showed them mercy by His retort, “Let anyone who is without sin, cast the first stone.” He gave the mob room to see its error. The Gospel of John (8:3-11) points out the seemingly insignificant detail that Jesus looked down so that they could walk away while saving face.

At the same time, Jesus healed the woman, wounded by her own sinfulness and maltreated as a pawn by the mob. He sends her off, with the consolation of “Neither do I condemn you. Go your way, and from now on do not sin again” (John 8:11). Our Lord showed that the mob, the world, CAN learn the truth about sin and redemption. He showed her that compunction was enough to receive mercy and the need to learn from one’s sins. He did not tell her not to pay attention to the Pharisees — in fact, in another place Jesus warned the people, “Obey them and do everything they tell you. But do not do what they do, for they do not practice what they preach” (Matthew 23:3). He didn’t say they were not qualified for the job as Pharisees because they were sinful. He also told her to learn from the mercy she received and to put aside her sinfulness. All of that is an important meditation for us because little mercy is being shown priests.

When I think of Father Gordon MacRae and the injustice he is enduring with such equanimity and grace, I am reminded that God’s grace is still active in this messy world. Beyond These Stone Walls is a visible sign of grace, allowing Father Gordon to preach from his pulpit, his unjust imprisonment, to make so many aware of the reality of injustice even in the Church. He and this blog are a sign of grace, a sign that such corruption is not a reason to turn against God or His Church but to work even harder to bring about a community of God-fearing men trying to live lives of virtue.

+ + +

Fr. Stuart MacDonald is a priest of the Diocese of St Catharines, Canada. Ordained in 1997, he is a graduate of McGill University, St. Augustine’s Seminary and the Pontifical Gregorian University where he earned a licentiate in Canon Law. In addition to being pastor of various parishes, he has worked as a judge and defender of the bond for the Toronto Regional Marriage Tribunal and as an official for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith at the Holy See. He is the author of several published articles on Canon Law and the priesthood. His most recent post for BTSW was “On Our Battle-Weary Priesthood.”

You may also want to read and share these related posts: