“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

I have Seen the Fall of Man: Christ Comes East of Eden

The Genesis story of the Fall of Man is mirrored in the Nativity. Unlike Adam at the Tree of Knowledge, Jesus did not deem equality with God a thing to be grasped.

The Genesis story of the Fall of Man is mirrored in the Nativity. Unlike Adam at the Tree of Knowledge, Jesus did not deem equality with God a thing to be grasped.

December 17, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

Back in 2014, one of our readers sent me an article that appeared inCrisis Magazine, “Who will Rescue the Lost Sheep of the Lonely Revolution?” by the outstanding writer, Anthony Esolen. It is an admonitory parable about the lost sheep of the Gospel and the once-dead prodigal son of another parable. What exactly did Jesus mean by “lost” and “dead”?

Mr. Esolen raises questions about controversies I had been taking up in previous weeks, perhaps most notably in “Synodality Blues: Pope Francis in a Time of Heresy.” Some of my posts then had a focus on the Parable of the Prodigal Son, so central to the Gospel, but Esolen makes a point missing from the Synod debate:

“That is why you came among us, to call sinners back to the fold. Not to pet and stroke them for being sinners, because that is what you mean by ‘lost,’ and what you mean by ‘dead’ when you ask us to consider the young man who had wandered into the far country. The father in your parable wanted his son alive, not dead.”

In over thirty years in prison, I have seen firsthand the fall of man and its effects on the lives of the lost. No good father serves them by inviting them home then leaving them lost, or worse, dead; deadened to the Spirit calling them out of the dark wood of error. Mr. Esolen has seen this too:

“…you say your hearts beat warmly for the poor. Prisoners are poor to the point of invisibility… Go and find out what the Lonely Revolution has done to them. Well may you plead for cleaner cells and better food for prisoners, and more merciful punishment. Why do you not plead for cleaner lives and better nourishment for their souls when they are young, before the doors of the prison shut upon them? Who speaks for them?”

Here in prison, writing from the East of Eden, I live alongside the daily consequences of the Fall of Man. It will take more than a Synod on the Family to see the panoramic view I now see. Anthony Esolen challenges our shepherds: “Venturing forth into the margins, my leaders?… [Then] leave your parlors and come to the sheepfold.”

In the Image and Likeness of God

Adrift in synodal controversy, we might do well this Advent to ponder the Genesis story of Creation and the Fall of Adam. I found some fascinating things there when I took a good long look. The story of Adam is filled with metaphor and meaning that frames all that comes after it in the story of God’s intervention with Salvation History.

Accounts of man created from the earth were common in Ancient Near Eastern texts that preceded the Book of Genesis. The Hebrew name for the first human is “ha-Adam” while the Hebrew for “made from earth” is “ha-Adama” which some have interpreted as “man from earth.” Thus Adam does not technically have a name in the Genesis account. It is simply “man.” His actions are on behalf of all.

As common as the story of man from the earth was in the texts of Ancient Near Eastern lore, the Biblical version has something found nowhere else. In Genesis (2:7) God formed man from the ground “and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life.” And not only life, but soul, life in the image and likeness of God. The Breath of God, or the Winds of God, is an element repeated in Sacred Scripture in a pattern I once described in an article entitled “Inherit the Wind.” To save you some time, we just discovered this AI overview of it:

“Inherit the Wind: Pentecost and the Breath of God” refers to a theological theme, particularly from writer, Father Gordon MacRae, connecting the biblical concept of “inheriting the wind” (Proverbs 11:29, meaning futility/foolishness) with Pentecost, where the Holy Spirit arrives as wind (Ruah in Hebrew) and breath, bringing life, understanding, and new creation, contrasting worldly futility with spiritual fulfillment. It uses “wind” (a symbol of God’s Spirit) to explore how believers receive divine life, moving beyond empty pursuits to a deeper, shared faith, just as the Apostles understood each other’s languages at Pentecost.

The title, “Inherit the Wind: Pentecost and the Breath of God” draws a parallel between the empty “inheritance” of the world (wind) and the profound gift of the Spirit (wind/breath) at Pentecost, which brings true substance and unity.

It signifies that instead of pursuing futile worldly gains (“inheriting the wind”), believers receive God’s Spirit, which transforms them into new creations and empowers them to share the Gospel, effectively reversing the confusion of Babel.

Back to our Genesis account: God will set the man from earth in Eden. Then in the following verse in Genesis (2:8) God establishes in Eden what would become the very instruments of man’s fall: the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and the Tree of Life. So what exactly was Adam’s “Original Sin?”

When I wrote “Science and Faith and the Big Bang Theory of Creation” I delved into the deeper meaning of the first words in Scripture spoken by God, “Let there be light” (Genesis 1:3). Saint Augustine in the Fifth Century saw in that command the very moment God created the angelic realm, a sort of spiritual Big Bang. What is clear is that spiritual life was created first and the material world followed. For all we know — and, trust me, science knows no better — “Let there be light” was the spark that caused the Big Bang.

You might note that the creation of light preceded the creation of anything in the physical world that might generate light such as the Sun and the stars. Saint Augustine then considered the very next line in Genesis (1:4), “God separated the light from the darkness,” and saw in it the moment the angels fell and sin entered the cosmos. It was only then in the Genesis account that construction of the material universe got underway.

When God created a man from the earth, a precedent for “The Fall” had already taken place. God then took ha-adama, Adam, and commanded him (2:16) to eat freely of the bounty of Eden, “but of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil you may not eat, for in the day you eat of it, you shall die.” Die not in the sense of physical death — for Adam lived on — but in the spiritual sense, the same sort of death from which the father of another famous parable receives his Prodigal Son. “Your brother was dead, and now he is alive” (Luke 15:32).

The Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil is what is called a “merism” in Sacred Scripture. It acts as a set of bookends which include all the volumes in between. Another example of a merism is in Psalm 139:2, “You know when I sit and when I stand.” In other words, “you know everything about me.” The Tree of Knowledge, therefore, is access to the knowledge of God, and Adam’s grasping for it is the height of hubris, of pride, of self-serving disobedience.

In the end, Adam opts for disobedience when faced with an opportunity that serves his own interests. From the perspective of human hindsight, man was just being man. In an alternate creation account in Ezekiel (28:11-23), God said to the man:

“You corrupted your wisdom for the sake of splendor, and the guardian cherub drove you out.”

God’s clothing Adam and Eve — who is so named only after The Fall — before expelling them is a conciliatory gesture, an accommodation to their human limitations. Casting them out of Eden is not presented solely as God’s justice, but also God’s mercy to protect them from an even more catastrophic fall, “Lest he put forth his hand and take [grasp] also from the Tree of Life” (Genesis 3:22).

Jesus in the Form of God

The Church’s liturgy has always been conscious of the theological link between the fall of Adam and the birth of Christ. For evidence, look no further than the Mass Readings for the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception. I also find a stunning reflection of the Eden story in a hymn from the very earliest Christian church — perhaps a liturgical hymn — with which Saint Paul demonstrates to the Church at Philippi the mission, purpose, and mind of Christ. “Let each of you look not only to his own interests, but also the interests of others. Have this mind among yourselves which was in Christ Jesus…”

“…Who though he was in the form of God did not deem equality with God a thing to be grasped at, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient unto death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed upon him the name which is above every other name, that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue proclaim to the glory of God the Father: Jesus Christ is Lord.”

— Philippians 2:3-11

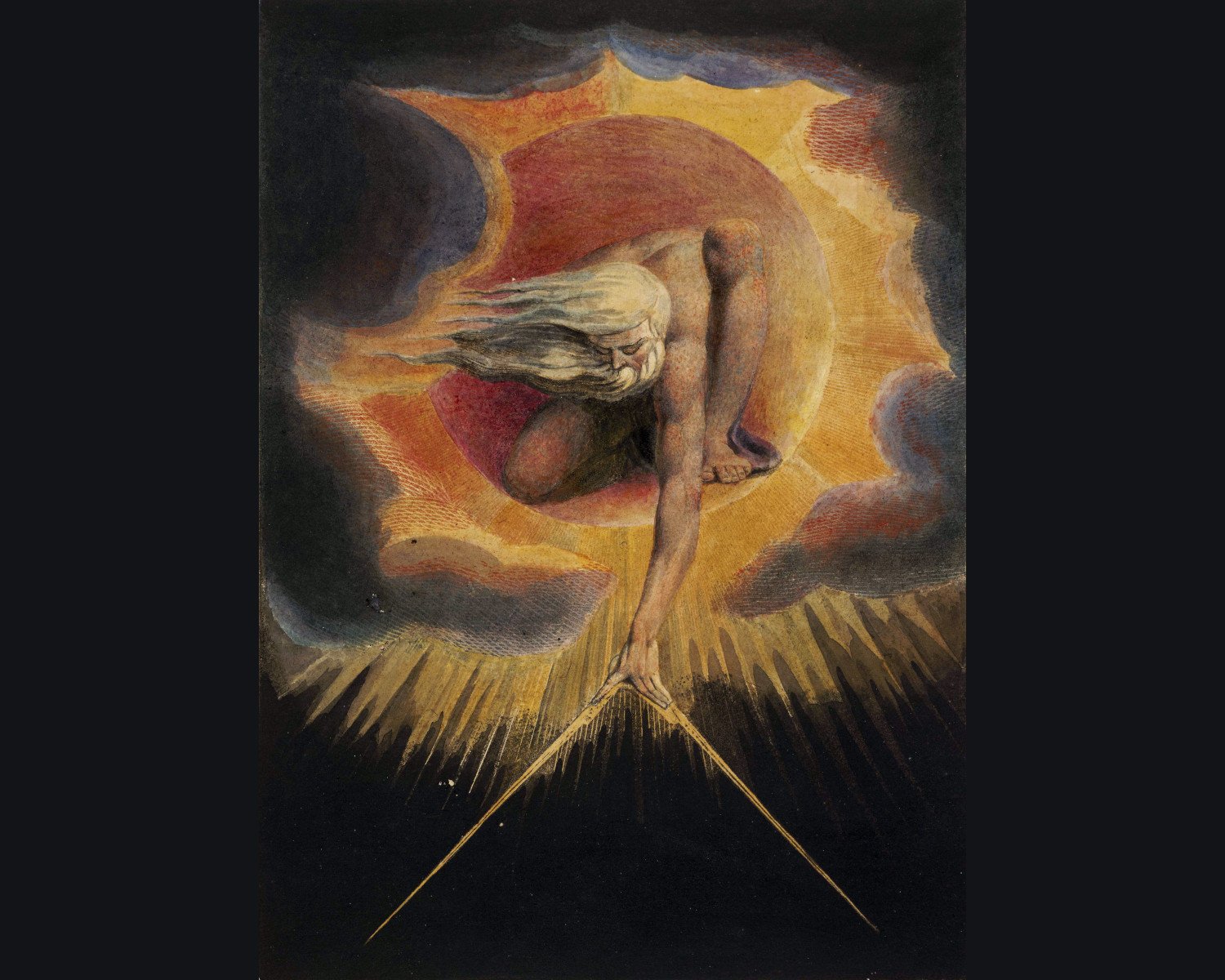

The two accounts above — the story of Adam fallen from the image and likeness of God and expelled from Eden, and the story of Jesus in the form of God “being born in the likeness of men” — reflect the classic dualism of Plato. A Greek philosopher in the 3rd and 4th Century B.C., the essence of Plato’s thought was his theory of image and form. Forms or universalities in the spiritual realm had imperfect reflections in the material world.

Hence, Adam is in the image of God, and falls, but Christ is in the form of God. The verses recounted by Saint Paul in Philippians point to something of cosmic consequence for the story of the Fall of Man. Man, made from the earth in the image of God grasps to be like God, and falls from grace at Eden. At Bethlehem, however, God Himself traces those steps in reverse. He comes to earth taking the image and likeness of man, and sacrifices Himself to end man’s spiritual death.

The late Pope Francis summoned us to extend our gaze to the peripheries of a broken world. It is a cautious enterprise in a self-righteous world in a fallen state. Without a clear mandate from the Holy Spirit, we could lose ourselves and our souls in such an effort. Anthony Esolen expresses the danger well in the Crisis article cited above:

“Who speaks for the penitent, trying to place his confidence in a Church that cuts his heart right out because she seems to take his sins less seriously than he does.”

We can bring no one to Christ that way, but the caution should not prevent the Church from her mission to reach into the ends of the earth, to save sinners, and not just revel with the self-proclaimed already saved. Ours is a mission extended to the fallen.

I have seen the Fall of Man — where I now live I see it all around me — and so had the Magi of the Gospel who came from the East to extend to Him their gifts. “Upon a Midnight Not so Clear, Some Wise Men from the East Appear” is my own favorite Christmas post, and one I hope you will read and share in the coming days.

They represent the known world. They came to bend their knee in the presence of Christ in the form of God born in the likeness of men at Bethlehem. Even my own aching, wounded knee must bend for that!

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for taking the time to prayerfully read and share this post, which I hope draws us away from the dark wood of error toward the wood of the Cross and our Salvation. You may also like these related Yuletide posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Saint Gabriel the Archangel: When the Dawn from On High Broke Upon Us

The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God

Upon a Midnight Not So Clear, Some Wise Men from the East Appear

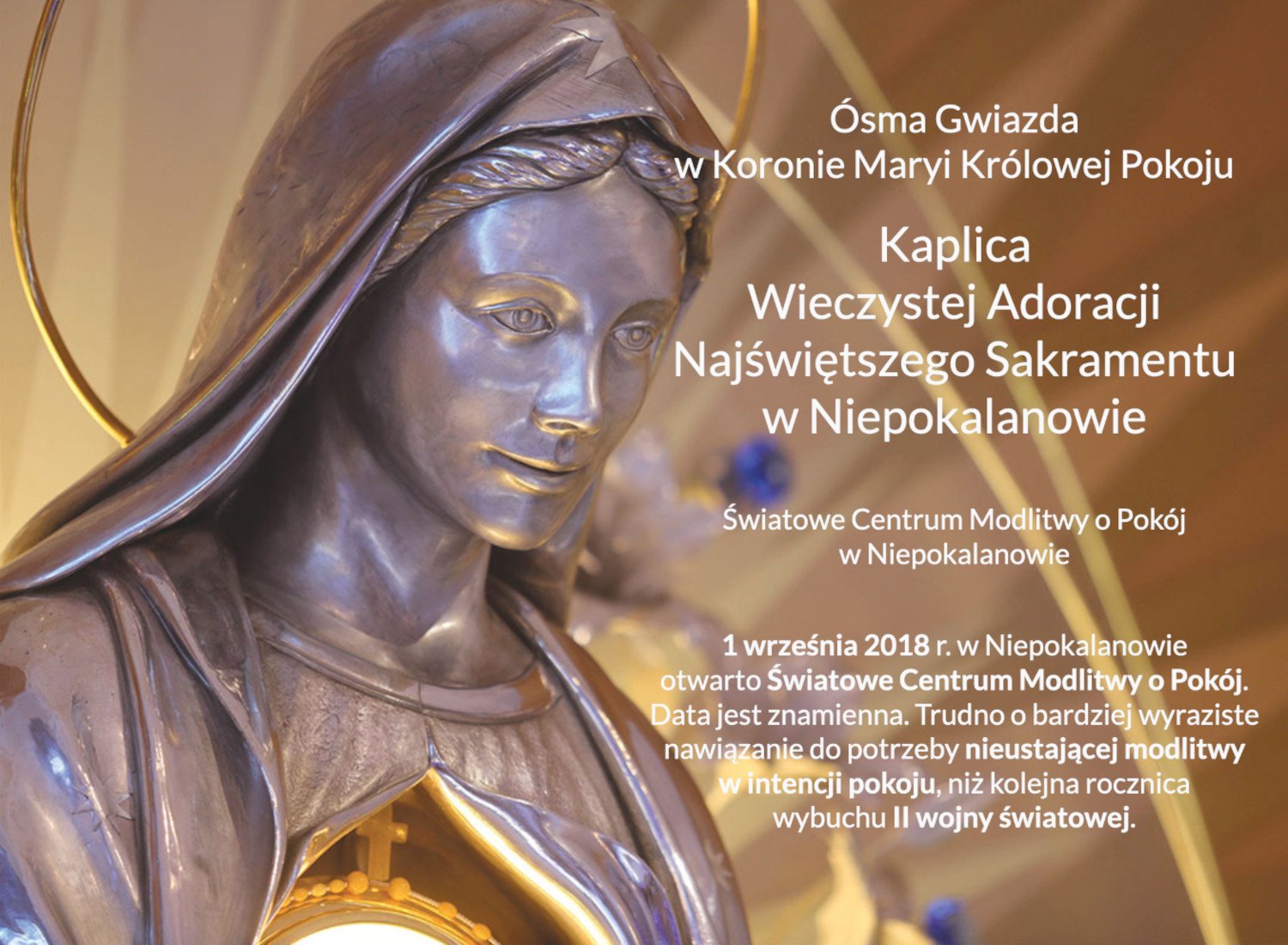

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The God of the Living and the Life of the Dead

The commemoration of our beloved dead on All Souls Day has roots in ancient Christian tradition, Faith in the God of Life in the land of the living survives death.

The commemoration of our beloved dead on All Souls Day has roots in ancient Christian tradition, Faith in the God of Life in the land of the living survives death.

Introduction from Fr. Gordon MacRae: In the last days of October 2020, I wrote a special post to commemorate All Souls Day and to honor our beloved dead. One reviewer called it “A tour de force of Sacred Scripture on the most crucial question of all time: the meaning of life and death.” I’m not sure it actually rises to that level, but I thought it was an okay post.

It was the last one published at These Stone Walls, the older version of this blog that one week later was taken down and then reborn anew as Beyond These Stone Walls. I wrote of how and why that happened in “Life Goes On, Behind and Beyond These Stone Walls.”

It was not planned this way, but my post to mark the commemoration of All Souls was published in the midst of a global pandemic just days before the most contentious U.S. presidential election of modern time. That was also the time in which my friend, Pornchai Moontri, had been handed over to ICE for a long and grueling ordeal leading up to deportation to his native Thailand.

For many readers, my All Souls Day post was relegated to a far back burner then so I have decided to rewrite it and post it anew. It is, after all, a matter of life and death. Please ponder it and share it with others.

Like all of you reading this, I, too, have been touched by death in ways that have changed my life. I once wrote of how death left me not only grieving, but entirely alone and stranded. It was a post about the essence of Purgatory and why it should not be feared. That post — which I highly recommend if you have ever been touched by death, is “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.”

It is one of the mysteries of Sacred Scripture that certain concepts exist there in almost equal measure with their polar opposites. I wrote during Holy Week, 2020, of the presence of both good and evil at the same table in “Satan at the Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light.” Many readers expressed amazement at my revelation that the concepts of light and darkness are represented in Scripture in almost equal measure, but with light just only slightly more prevalent.

I was surprised, for this post, to discover that the same is true in the matter of life and death. I conducted some research into the various permutations of the word, “death” in Sacred Scripture. The terms, death, dead, die, died, and killed have a combined appearance for a total of 1,620 times in our Old and New Testaments. The same research into occurrences of the word, “life” included the terms, life, alive, living, lives and lived. The combined appearances of “life” totaled 1,621. Pro-life wins!

Our Scriptures, and especially their revelations in the words of Jesus who had … well … the “inside scoop,” not only give life and death almost equal weight, but place them on a continuum. This becomes most evident in a challenge of Jesus to the Sadducees who rejected any notion of an afterlife or resurrection:

“You are wrong, because you know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God … And as for the resurrection from the dead, have you not read what was said to you by God? ‘I am the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.’ He is not the God of the dead, but of the living.”

Jesus was citing the Book of Exodus (3:1-6) and the story of Moses’ first encounter with God in the burning bush. By Yahweh’s self-description that he is the God of these Patriarchs who died long ago, Jesus brings his listeners to a conclusion that they must still live for God to still be their God. Their ongoing presence with God is the decisive precondition for future resurrection.

For Jesus, this ongoing presence of the soul with God is a continuation of the very life you know — but without the excess baggage. What must such a state be like? I sometimes hear from people who long to have some affirmation from their departed loved ones that they still exist. Do we really need such evidence? One of the most hopeful verses in all of Scripture comes from Saint Paul’s Letter to the Colossians, and it has an answer:

“If with Christ you died to the elemental spirits of the universe, why do you live as if you still belonged to the world?… If then you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above where Christ is seated at the right hand of God. Set your mind on things that are above, not on things that are on Earth. For you have died, and your life is now hidden with Christ in God.”

The Resurrection and the Life

There is another way to phrase what I wrote above: “For Jesus, this ongoing presence of the soul with God is a continuation of the very life you know…” It is also a continuation of the very life that knows you. It is that which is imparted in our ensoulment as being “in the image and likeness of God” (Gen. 1:26). In the Biblical account of creation, filled with rich theological meaning, “The Lord God formed man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being” (Genesis 2:7). I wrote of this once in “Inherit the Wind: Pentecost and the Breath of God.”

What animates us, what makes us living beings in the image of God, is that which survives the body. In Biblical Hebrew, the word that is translated in English as “soul” is “nepeŝ.” A survey of its use throughout the Hebrew Scriptures shows that there is no adequate word in English that captures its meaning. In the Genesis account of the creation of man, it means the totality of the self, both one’s spiritual and physical being. The Prophet Jeremiah shows that we can prove our nepeŝ to be righteous (3:11), that we must not try to deceive our nepeŝ (37:9), or expose our nepeŝ to evil (26:19).

It is, for the Prophet Ezekiel, the source of our capacity for empathy; “To know the nepeŝ of the stranger” is to know how it feels to be a stranger (Ezekiel 23:9). It is the subject of human attributes of the heart (Psalm 139:14, Proverbs 19:4). It is also a source of our consciousness (Esther 4:13, Proverbs 23:7). There are 317 references to it in the Hebrew Scriptures. In the New Testament, it is that which, for Mary, “magnifies the Lord” (Luke 1:46).

Of interest, in the Greek of the New Testament, “nepeŝ” is translated as “psyche.” It is the source of one’s consciousness and life. Some Scripture scholars equate the “ego” of Freudian psychology as coming closer to the meaning of nepeŝ than any other word. It is the source of one’s self, one’s identity and self-awareness. It is what remains of the immortality lost in Eden and restored in Christ. Our nepeŝ survives our death.

To believe in God and not believe in the reality of our soul is folly. Hope, the assurance of salvation, is the anchor of the soul (Hebrews 6:19). The New Testament presentation of the immortality of the soul is not a new idea, but a radically new revelation of the meaning of life and salvation illuminated by the Resurrection of Jesus.

The word, “resurrection” appears only twice in Hebrew Scripture, and both are in the Second Book of Maccabees. When Eleazar and seven brothers were being tortured to death for their fidelity to God, one of the brothers proclaimed to Antiochus the king:

“I cannot but choose to die at the hands of men and to cherish the hope that God gives of being raised again by him. But for you there will be no resurrection to life.”

That account is also referenced in the Book of Daniel (3:16-18). It was written in about 150 BC during the emergence of a Messianic Age in Judaism. The other account found in Second Maccabees also presents Biblical support for the existence of Purgatory and the Spiritual Work of Mercy to pray and atone for the dead:

“The noble Judas (Maccabeus) took up a collection … and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. In doing this, he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection … therefore he made atonement for the dead that they might be delivered from their sin.”

Almost Heaven

Despite the famous song of John Denver, Heaven is not in West Virginia. Not even almost. I take the liberty of capitalizing it because what the Hebrew Scriptures refer to as “Heaven” and “the heavens” are two different places. The heavens refer to the ancient Semitic conception of the visible Universe. God is there, but only because He is everywhere. “Heaven,” on the other hand, refers to the dwelling place of God. In modern translation, it has 575 references in Sacred Scripture as opposed to 113 for “the heavens.”

There are multiple passages in both Testaments of Scripture that refer to Heaven as the dwelling place of God, but in some, the dwelling of God is said to be in the “Heaven of Heavens,” or in “the Highest Heaven” (see Deuteronomy 10:14, 1 Kings 8:27, and Psalm 148:4). Hebrew literature was influenced by the use of the Hebrew word, “ŝamāyim” for Heaven, though it is in the plural. There are obscure references to stages or levels of Heaven. Being a Jew educated in the traditions of the Pharisees, this conception was the basis for Saint Paul’s description (2 Corinthians 12:2) that he was taken up to the Third Heaven which is identified with Paradise:

“I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third Heaven – whether in the body or out of the body, I do not know. God knows. And I know that this man was caught up into Paradise.”

I wrote of the Scriptural use of the word “Paradise” some years ago in one of the most-read posts on Beyond These Stone Walls, “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” The Greek term, “Parádeisos, came into Greek from the Akkadian term for Paradise. It is used three times in the New Testament: here, in St. Paul’s reference to Heaven; In the Book of Revelations (2:7) as the eternal dwelling that awaits the saints; and in the above-cited link referencing the Gospel of St. Luke (23:43) and his account of the words of Jesus to the criminal who comes to faith while being crucified next to Him: “Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

The same term, Parádeisos, appears in the Septuagint, the only surviving translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. The word, “Septuagint” means “seventy,” referring to the number of Greek translators of the Hebrew Bible who developed it in the Second Century B.C. It is sometimes referred to by its Roman numerals: The LXX. Back to my point, the word, “Parádeisos” makes its first Biblical appearance in Genesis 2:8. It was a reference to the original state of Eden before the Fall of Adam, a state restored to human souls on the Cross of Christ.

It is the inheritance of true discipleship, the qualities of which are described in the Judgment of the Nations (Matthew 25:31-46). One of them is that “when I was in prison you came to me.” If you are reading this, then you have fulfilled that tenet. Jesus told us that His Father’s House has many mansions. In his parting words to me, my friend, Pornchai Moontri, said that we will next meet there — and we will one day have a house there — and it will be more than 60-square feet!

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please share this post and join us in prayer for our beloved dead family and friends on All Souls Day and throughout November.

You may also wish to read and share these related posts:

The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts