“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Saint Maximilian Kolbe: A Knight at My Own Armageddon

An empty vessel reduced to a cloud of smoke and ash above Auschwitz, this Patron Saint of Prisoners, Priests, and Writers remains a Knight at the Foot of the Cross.

An empty vessel reduced to a cloud of smoke and ash above Auschwitz, this Patron Saint of Prisoners, Priests, and Writers remains a Knight at the Foot of the Cross.

August 13, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

This post started out as Part 2 of another post from back in 2016. It was “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night.” That post describes my own Dark Night of the Soul when all light and hope went out of the world for me. I somehow survived it mentally and spiritually. The scene above would much later come to have a lot to do with my survival of that Dark Night. The scene took place in 1982, the year of my priesthood ordination. It depicts Pope John Paul II at the Mass of Canonization of Saint Maximilian Kolbe. The person in front of him is Father James McCurry, OFM Conv, who was the Vice Postulator for the Cause of Sainthood of Father Maximilian. The scene is taking place 41 years after Maximilian was martyred at Auschwitz. Another 24 years after this scene, in 2006, Father McCurry rather mysteriously, through a series of unknown connections came to visit me in prison. Our visit began with a question: “What do you know about Saint Maximilian Kolbe?”

At that time, I knew very little. I knew that he had been canonized at the time of my ordination. I was somewhat preoccupied then, and never gave him a second thought. I had no idea at the time of the amazing graces to come through this great saint, and not only for me. He appeared among the wreckage of my own Armageddon.

On its face, “Armageddon” seems an exaggerated word to define any battle you can personally endure — until you actually endure it. For some who have lived through the torment of an inner battle, there is no word that captures it better. The word, “armageddon” calls forth images of the End Time, the apocalyptic battle between Good and Evil and the Final Coming of Christ. It is a mysterious word that appears in only one place in all of Sacred Scripture, a single word in a single line in The Book of Revelation, also called, “The Apocalypse”:

“And I saw, issuing from the mouth of the dragon, and from the mouth of the beast and from the mouth of the false prophet, three foul spirits … for they are demonic spirits, performing signs, who go abroad to the kings of the whole world, to assemble them for battle on the great day of God the Almighty. (‘Lo, I am coming like a thief! Blessed is he who is awake keeping his garments, that he may not go naked and be seen exposed!’) And they assembled them at the place which is called in Hebrew, ‘Armageddon’.”

— Revelation 16:13-16

The word, “Armageddon” comes from the Hebrew, “har Megiddôn, which means the “hill of Megiddo.” It was the site of several decisive battles in Israel’s Biblical history (see Judges 5:19; 2 Kings 9:27; and 2 Chronicles 35:22). In common usage from that one source, “Armegeddon” has also come to refer to any epic or pivotal battle or struggle between good and evil, even one within ourselves.

For me, the battle for hope, for truth, for justice that brought about the shattering of my life and priesthood, the battle in which I fell, leaving behind an empty vessel, has been the source of a sort of personal Armageddon. That account was told in these pages in my post, “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night.”

I know that among our readers there are many whose lives, at some point or other, have been shattered in similar ways. Through illness, great loss, alienation, even betrayal, they know what I mean when I write as I did in that post that the collapse of hope and faith leaves us as an empty vessel. In such a state, the struggle between Good and Evil is at a crossroad. Like many of you, I have stood empty and lost at that crossroad, and often the road less traveled, the one to redemption, seems at that time to be the more arduous one. It seems easier to just give up.

I receive many letters from people who have been where I was then, some who are there even now, and all are seeking one thing: a guide to traverse the inner darkness, to fill the emptiness that sickness, loss, abandonment, betrayal, and injustice leave behind. I have known some, including some good priests, who have utterly lost their faith in the midst of such a personal Armageddon. In this struggle, our Patron Saints are not just here to intercede for us. They are here to be our guides and shield bearers in the midst of battle.

We have a tendency to see the earthly lives of our saints as somehow enraptured in some inner beatific vision just waiting for release from this life, but they were as vulnerable to this world as the rest of us. I once wrote of one of my spiritual heroes, the great Doctor of the Church, Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, in “A Shower of Roses.” Saint Thérèse knew suffering that would have drawn her to despair if not for faith. In the days between August 22 and 27, 1897, her tuberculosis reached the peak of suffering. In an entry in her diary at that time, she wrote that her faith was all that stood between her and an act of suicide:

“What would become of me if God did not give me courage? A person does not know what this is unless he experiences it. No, it has to be experienced! What a grace it is to have faith. If I had no faith, I would have inflicted death upon myself without hesitating a moment.”

— Story of a Soul, Third Edition, ICS Publications, p. 264

Thanks to that unexpected visit in 2006, when I was on the verge of spiritual collapse, Maximilian Kolbe came to become my Patron Saint. Several days after that visit with Father McCurry, I received from him in the mail, a note with a laminated card depicting Saint Maximilian half in his Auschwitz prison uniform and half in his Franciscan habit. I should not have received that image at all. Such inspiring and hopeful things are considered contraband here. Marveling over how it made its way to my cell, I taped it onto the battered mirror on my cell wall. After that day, I learned everything I could about Maximilian Kolbe including a biography of his life by Father James McCurry OFM Conventual.

Maximilian Kolbe and His Noble Resistance

Back in 2016, at the time I wrote about Father Benedict Groeschel and my Darkest Night, The Wall Street Journal carried a story by Vatican correspondent Francis X. Rocca entitled, “Pope Honors Victims of Auschwitz” (WSJ, July 30-31, 2016). I was surprised to see within it a reference to our Patron Saint:

“The pope walked unaccompanied through the camp’s entrance gate, passing under the arch bearing the infamous phrase, ‘Arbeit macht frei,’ German for ‘Work will set you free.’ He then went to the spot in the camp where St. Maximilian Kolbe, a Franciscan priest, volunteered on July 29, 1941, to die in the place of a condemned prisoner. In Cell 18 of Block 11, the ‘starvation cell’ where Kolbe subsequently died on August 14, 1941, Pope Francis sat alone in semidarkness to pray before an image of the saint.”

The imagery here struck me very hard. I wrote back then of the crushing injustice of false witness, of the greed enabled by the now broken trust between priests and their bishops, and of the sense of utter hopelessness found in the prospect of unjust imprisonment, possibly for the rest of my life. The events I described in “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night” took place a year before my trial. During that year came the multiple attempts to entice me into lenient “plea deals” — first an offer to serve one-to-three years in prison, then reduced to one-to-two. If you have read The Grok Chronicle Chapter 1 then you already know of my refusal to “just go along.”

My refusal of these deals was met not just with condemnation from the State, but also from the Church, or at least from those charged with the administration of my diocese. After I refused these convenient deals, my bishop and diocese released unbidden a statement to the news media pronouncing me guilty before jury selection in my trial. It was that betrayal that led inexorably to the events of my Darkest Night.

There is no way to cushion what I faced after emerging from Intensive Care as an empty and discarded vessel. As I described in that post, I, too, sat in semidarkness, but by that point I knew nothing of either the sacrifice or the resistance of Saint Maximilian Kolbe. Long time readers of these pages also know the story of how he injected himself not only into my prison, but also into that of Pornchai Maximilian Moontri. This account has appeared in a number of posts, but most importantly in “The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner.”

Whatever I endure pales next to what happened in the prison of Maximilian Kolbe. His “crime” against the Third Reich was his insistence on writing openly about hope and truth when all of Europe was descending into darkness. There is a very important element of the story of Maximilian Kolbe’s sacrifice in prison, and it was to become the first sign of hope for me and others behind these prison walls. Like the Gospel itself, there is an historical truth within the story, but then there is another level of meaning in how the story was interpreted, how it inspired those whose lives were changed by it. The story of what Maximilian did in that prison was not just an act of sacrifice that saved the life of one man. It was an act of resistance that spread through all of Auschwitz and the other death camps, and emboldened many with hope to survive. This aspect of the story is told best in an unusual place.

Hermann Langbein (1912 – 1995) was a survivor of the horrors of both Dachau and Auschwitz. After the liberation of the camps, he became general secretary of the International Auschwitz Committee during which he wrote two important books published in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The first was Against All Hope: Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps. The second was People of Auschwitz (University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

In the latter, as a member of the Auschwitz resistance, he profiled those among his fellow prisoners whose acts of resistance empowered others to hope. There were other

courageous acts of resistance at Auschwitz. Prisoner Albert Benaviste, a Jew from Saloniki, learned that none of the camp guards understood Greek. While working at the entrance ramp to Auschwitz, he called to Jewish mothers in Greek, mothers who had been deported from his homeland. He called in Greek, “You young mothers, give your children to an older woman near you. Elderly women and children are under the protection of the Red Cross!” This act of resistance saved many lives, for elderly women alone, and young children alone were destined to die in the gas chambers. But the best known act of resistance, Hermann Langbein wrote,

“was that of Maximilian Rajmund Kolbe who deprived the camp administration of the power to make arbitrary decisions about life and death.”

— People of Auschwitz, p. 241

“Where Was God in Auschwitz?”

Seeing the meaning of this story through the eyes of a fellow prisoner, a Jewish prisoner, brings an important element of resistance to the story that Langbein tells in his own words:

“Kolbe, a Catholic clergyman, arrived in Auschwitz on May 29, 1941. When an inmate made a successful escape in July of that year, the administration ordered the reprisal that was usual at that time. The inmates of the escapee’s block had to remain standing after the evening roll call. Karl Fritzsch, the SS camp leader, picked out fifteen men, and everyone knew that they would be locked up in a dark cell in the bunker where they would have to remain without food and water until the escapee was caught or they died.”

— People of Auschwitz, p. 241

One of the young men lined up that day was Franz Gajowniczek, who was one of the last selected for death by the SS officer. The young man cried, “My wife and children! What will happen to my family?” What happened next is described by an eyewitness, Dr. Franz Wiodarski, a Polish physician who also stood in that line:

“After the fifteen prisoners had been selected, Maximilian Kolbe broke ranks, took his cap off, and stood at attention before the SS camp leader, who turned to him in surprise: ‘What does this Polish swine want?’ Kolbe pointed at Gajowniczek, who was destined for death, and replied: ‘I am a Catholic priest from Poland. He has a wife and children, and therefore I want to take his place.’ The SS camp leader was so astonished that he could not speak. After a moment he gave a hand signal and spoke only one word: ‘Weg!’ (Away!). This is how Kolbe took the place of the doomed man, and Gajowniczek was ordered to rejoin the lineup.”

— People of Auschwitz, p. 241

“Resistance in an extermination camp meant the protection of life,” wrote Hermann Langbein in his interpretation of this story. With the eyes of faith, we see Saint Maximilian Kolbe as a martyr of charity, but for those imprisoned at Auschwitz his act was an act of resistance that diminished the SS leader in the eyes of other prisoners as a man spiritually bankrupt.

Father Dwight Longenecker wrote an article back then for Aleteia entitled “Maximilian Kolbe and the Redemption of Auschwitz.” It describes a pilgrimage to the site of Saint Maximilian’s martyrdom. “It is impossible to take it in,” he wrote, “and quickly process the truths you are learning. Like most, I had to ask where God was in the midst of such horror.” Father Longenecker found the answer:

“Where was God in Auschwitz? He was there in the prison cell, just as he was at the crucifixion of Christ, not defeating the evil with violence or force… Whenever and wherever possible we must do all we can to oppose evil by passive resistance, civil disobedience, protest, boycott, and even armed force, but when the evil is so overwhelming, when the stench of hell is so great and the hatred of Satan so violent as that of Auschwitz, one can only stand back, aghast and horrified by the hurricane of sheer unadulterate cruelty, torture, and premeditated murder. Then all resistance is futile.”

— Father Longenecker

Ah, but is it futile? Not in the bigger picture it isn’t. Saint Maximilian’s sacrifice — his act of resistance — has played out in my prison bringing hope and inspiring faith where otherwise they simply could not be. Spend some time in his honor with the links at the end of this post, and learn with us behind walls about the possibilities for the lives of others when evil is resisted.

There is a story from the early life of Rajmund Kolbe that is included in each of several biographies of his life, including the one by Father James McCurry. At age ten, his mother once asked him in exasperation, “Whatever will become of you?” It troubled Rajmund enough to send him to church to pray before a statue of the Mother of God. While there, he had a dream, or a vision. It was never really clear which. Mary presented him with two crowns, one red, and the other white. He chose them both. The symbolism of the two colors was a pivotal event in the life of the person who was to become Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

After writing of my wrongful imprisonment in The Wall Street Journal in 2005, Dorothy Rabinowitz challenged me in a telephone call to “emulate that Saint you have come to regard so highly. Find someone whose suffering is heavier than yours and then seek his freedom.” It was shortly after that this daughter of a Holocaust survivor sent me another challenge that would result in a post of my own. It was “Say Not the Struggle Naught Availeth.” It was also at just this time that Pornchai Moontri emerged from another concentration camp, thirteen years of hellish existence in solitary confinement in a Maine prison. He was transferred to this one and by some mysterious circumstance he became my cellmate. His first words to me while staring at the battered mirror on our cell wall with the image of our Patron Saint were, “Is this you?”

I had my first hint that Saint Maximilian was deeply at work in my prison when Pornchai Moontri made a decision to become Catholic on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010, and to take the name, Maximilian, as his Christian name. This was brought about by a series of events described in a chapter of a book by Felix Carroll, Loved, Lost, Found: 17 Divine Mercy Conversions.”

At the time, Pornchai decided to honor his new Patron Saint with an art form in which he had become a master craftsman, the art of model shipbuilding. So he meticulously designed a vessel that he would name the “St. Maximilian.” He proceeded in his work area in the prison woodworking shop to hand carve the bow, masts, and every tiny fitting, and to tie all the intricate rigging. Pornchai painted the hull black to symbolize the horror of where he died.

But then a few days later, while knowing nothing about the early life experiences of his new Patron Saint, Pornchai told me one morning that he had changed his mind, and had decided that the black hull will be crowned in red and white. This seemed to have come out of nowhere but inside Pornchai’s own soul where Maximilian was hard at work again saving a life.

I was startled by this choice of colors and asked him why he chose them. He said, “I don’t know. They just seem right.” So here below is the St. Maximilian, created by Pornchai Maximilian Moontri to honor his Patron Saint and to inform us all that resistance is not futile. Not ever!

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Don’t stop here. Learn more about how Saint Maximilian Kolbe led us to Christ through the Immaculate Heart of Mary:

How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

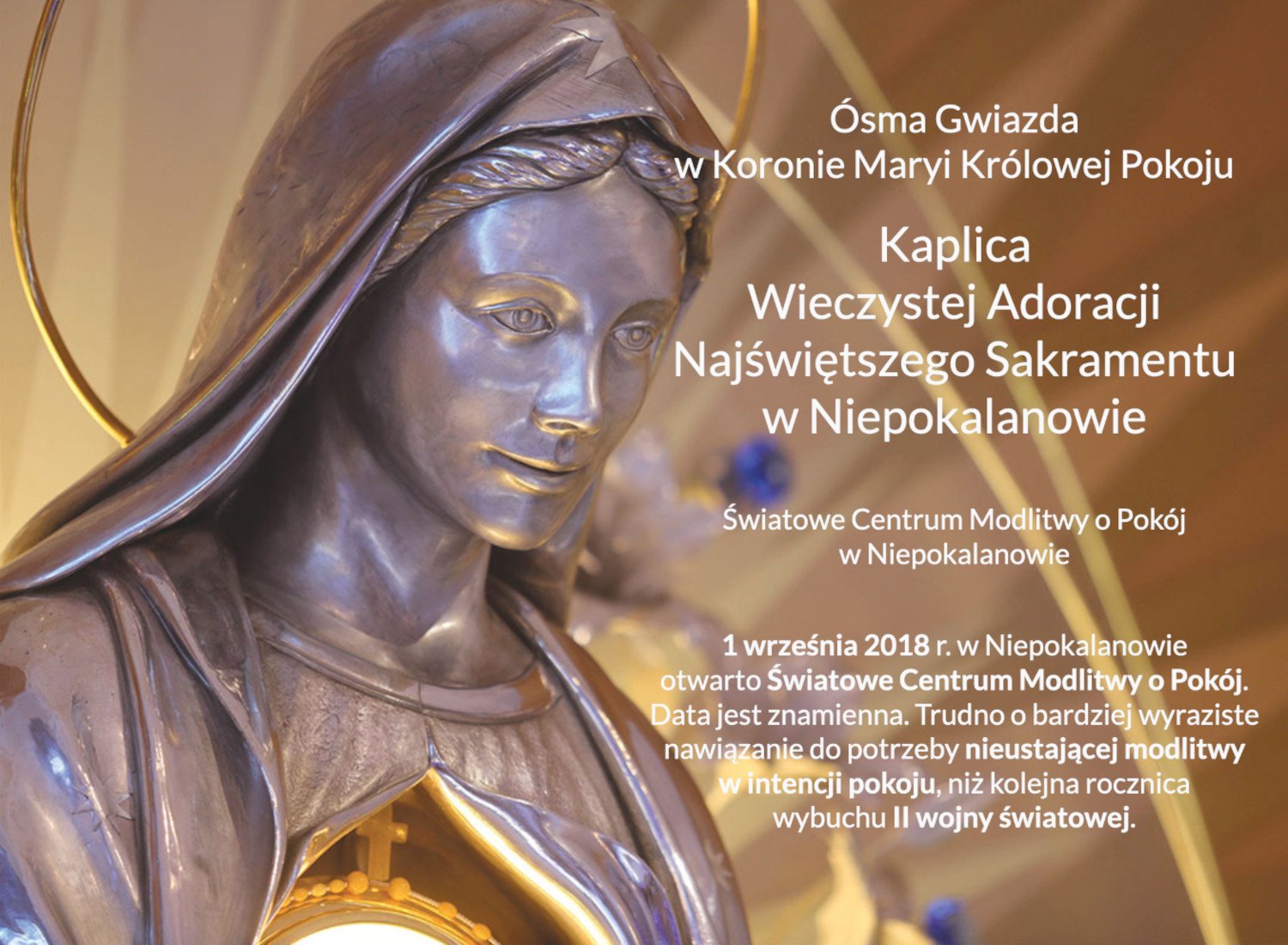

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

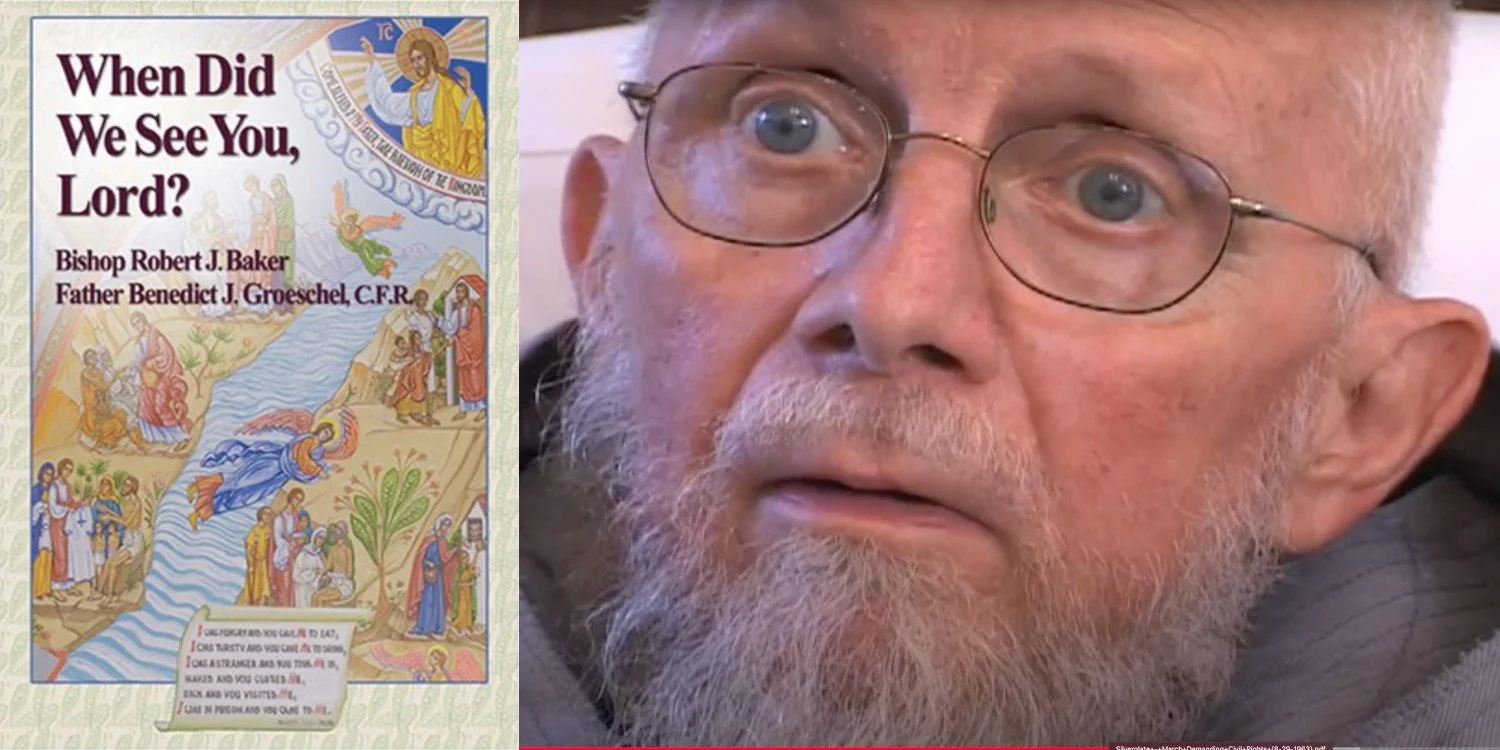

On the Road to Heaven with Father Benedict Groeschel, CFR

Seeing God in suffering in a world in semi-darkness is a great spiritual challenge of our age. Father Benedict Groeschel lived in cooperation with Divine Mercy.

Seeing God in suffering in a world in semi-darkness is a great spiritual challenge of our age. Father Benedict Groeschel lived in cooperation with Divine Mercy.

At the time of Father Benedict Groeschel’s death in 2014, I had known him for over 40 years. We were on the same path in life for quite some time. Even since his death, I continue to encounter him frequently. Even while writing this post, I picked up a book called The Lamb’s Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth by the great Scriptural theologian and Catholic convert, Scott Hahn. Just a few pages into it I noted that the Forward was written by Father Benedict Groeschel. The book was published in 1999, fifteen years before Father Benedict’s death. His six-page Forward contained one sentence that made me laugh out loud. It was vintage Benedict Groeschel: “As an inhabitant of New York City, the 20th Century candidate for Babylon, I am perfectly delighted with the prospect of it all ending soon, even next week.”

Father Groeschel wrote to me a few times in prison. In 2012, I wrote a controversial post about him. When he was falsely accused of wrongdoing, I took up a spirited defense of him. I hope you will read it. We will link to it again at the end of this post. It is, “Father Benedict Groeschel at EWTN: Time for a Moment of Truth.”

But that was not my only post about Father Groeschel.

When I wrote “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night,” I typed it from my heart without notes or drafts in a single sitting as I usually do.

A strange thing happened on the afternoon of Wednesday August 3, the same day my post about Father Benedict Groeschel was published at Beyond These Stone Walls. I was at work in the prison Law Library where I have been the clerk for a number of years. Someone dropped a trash bag full of books next to my desk. They were books that returned from various locations around the prison from prisoners in maximum security or other places who cannot personally come to the library.

I had to check all the books back into the library system and examine them for damage before putting them on a cart to be reshelved, then checking out new ones to send back to the men languishing in “the hole.” This library has about 22,000 volumes with 1,000 books checked in or out every week so the bag of books was nothing unusual.

But when I reached into the bag for a handful of books, the first one I looked at brought a jolt of irony. It was a little hardcover book I had never seen before. The book had once been in the library system, but was stamped “discarded” in 2005 which was about years before it showed up again. For over ten years the book traveled from place to place in this prison, finally ending up in a bag at my desk on that particular day.

When I looked at the book’s cover, I was stricken with the bizarre irony of it. On the same day we published “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night,” I was holding in my hand a little book titled, When Did We See You, Lord by Bishop Robert Baker and Father Benedict J. Groeschel published by Our Sunday Visitor in 2005.

I know that Father Groeschel has written many books, but I had never before seen one in this prison library. The “coincidence” of it showing up on that particular day wasn’t the only irony. The book is a series of meditations on Matthew 25:31-46, the Biblical source for the Corporal Works of Mercy. The book’s last chapter is titled “For I was in prison and you came to me.”

And if that still wasn’t irony enough, when I turned to the book’s preface, I read that it is based on a series of retreat talks given by Father Groeschel in 2002 to the bishop, priests and deacons of the Diocese of Manchester New Hampshire — my diocese — while I was in prison twenty miles away.

This is the one small thing that God and I have in common. We both really appreciate irony. I use it a lot when I write, and so does He. But in His hands it is a work of art. In the wonderful preface to this little book, Catholic writer and editor, the late Michael Dubruiel wrote:

“Sometimes, ironically, life imitates art: as this book was being written, Father Benedict was involved in a horrific accident that nearly took his life. At the time of the accident, the text he was working on was in his suitcase — the just finished Introduction to ‘For I was a stranger and you welcomed me,’ [Chapter 3 of When Did We See You, Lord?].”

Hopelessness and Suicide

In the introduction to his chapter entitled, “When I was in prison, you came to me,” Father Groeschel told a story very familiar to me. I knew him well fifty years ago when he and I were both members of the Capuchin Province of Saint Mary where I began my priesthood formation. Father Groeschel was the homilist for my first profession of vows which took place on August 17, 1975.

At the time, Father Benedict was chaplain of a facility for delinquent young men in upstate New York. Some of those young men later landed in prison so Father Groeschel was a frequent visitor to prisons throughout New York State. One day he went to one of them to visit a young prisoner he knew, but he arrived at an inconvenient time. All the prisoners were locked down for the daily count.

While he waited, one of the guards who knew him invited Father Groeschel to a prison lunch which he described as “nothing fancy, a bowl of starchy soup and some bread.” While he was eating, the guard came back and asked Father Groeschel to follow him quickly. A young prisoner had just hanged himself.

Father Groeschel and the guard went running up the stairs to the end of a cellblock. There on the floor was the lifeless body of a young man surrounded by guards and a prison doctor performing CPR. When the young prisoner regained consciousness, Father Groeschel bent over him and started to talk to him:

“He looked at me with this very beautiful smile — like he knew me, like he expected me to call him by name — and at first I couldn’t figure that out since I had never seen this boy before. Then I realized the boy thought he was dead. He had just hanged himself, and he opened his eyes to see this figure in a long robe and beard, and thought I was Someone else. I was horrified, so I moved my head so he could see the guards and ceiling of the cellblock. When I did so, he began to cry bitter tears, the bitterest tears I have ever seen… I was not the One he thought I was, but I was mistaken too. I thought he was just a prisoner when, indeed, he was the disguised Son of God.”

— When Did We See You, Lord?, p. 153

I was involved with a similar near tragedy in prison. It was in 2003, exactly six years before this blog began. It was not so overcrowded in this prison then. Bunks and prisoners did not fill the recreation areas outside our cells as they do today. One day in 2003 at about this time of year, late on a weekday morning, most of the prisoners from this cellblock had gone to lunch. I was reading a newspaper, enjoying the rare twenty minutes of quiet at a table outside my cell. In the distance, my mind registered a barely audible metallic click.

Over time in this place, every mechanical sound comes to have meaning, even sounds that register just below the level of consciousness. The clink of keys when a guard is approaching, the vague static sound the PA system makes just before a name is called, the electronic buzz of distant prison doors opening and closing. They all register just below the psyche.

That distant metallic click I heard that day also registered. It was the sound of a cell door locking, but the cell doors in this medium security prison are not locked during the day. I sat there alone with my newspaper, then suddenly looked up. My eyes scanned both tiers of cells in this cellblock. All the doors were slightly ajar except one, cell number six near the end of the row of cells where I live.

Not many prisoners would freely lock themselves in a cell midday, so I closed my paper and walked down the tier to that cell door. Through the narrow window in the locked door, I saw a young man standing on the upper bunk. He had taken a cord from somewhere and fed one end of it through the cell’s ceiling vent. He had tied the other end around his neck, and just as I got to the door, he jumped I watched in horror as he dangled, swinging and choking from the vent. There was no way I could get in that locked door and there was no one around. I shouted repeatedly at him to step back, onto the bunk.

Our eyes met, and what I saw was utter hopelessness. As the life was slowly choking out of him, nothing that I shouted made a difference. The seconds seemed eternal, but finally the first prisoner returning from lunch was buzzed through the cellblock door in the distance. Just before it closed behind him I yelled with all my might for him to get back out there and get the door to cell six open. The guy later said that I scared the hell out of him. He went to the control room and asked a guard to open cell six, which he did by pressing an electronic switch.

Finally, I heard the loud pop of the door’s lock disengaging and I swung the door open. The dangling prisoner was still. I rushed in and lifted him up while the other man ran to get

some help. Two guards came in and cut the young man down. We got the cord from around his neck and laid him on the cell floor. His breathing was labored, and the cord had left a deep gash around his neck that never fully disappeared. While he was being carried out of the cell by the guards, he cursed at me. He choked out the bitter words, but they were clear enough for me to understand. It was his version of bitter tears, and like those witnessed by Father Groeschel, they were the bitterest tears I have ever seen.

Once he was cleared from the Medical Unit, the young man was sent to the prison’s Secure Psychiatric Unit for several months. I saw him a few times after that when the prisoners there were permitted to come to the library. He always avoided eye contact with me, then one day I decided to broach the topic directly. “I’m not sure where you are with what happened,” I said, “but I do not regret what I did.” “Why did you stop me” he asked. I responded with as much kindness as I could summon:

“Because I once stood where you stand now, and have learned that we are the stewards, not the masters, of the life God has given us. What would it say about me if I ignored the Divine Mercy of the Author of Life?”

“Remember Those in Prison” — Hebrews 13-3

He looked at me thoughtfully for a few moments, then asked what I meant by “Divine Mercy.” I explained that there were many unusual factors that all had to be in place for me to be where I was at that very moment to hear his door click. One of them was that I was having a really bad day and needed twenty minutes of quiet so I skipped lunch. “That’s what I mean by Divine Mercy. It guided me to you in your time of need whether you even realize that it was a time of need. This happened because you thought you needed to die. God thought otherwise.” He considered this, nodded, then left with the bare hint of a smile. It dawned on me only well after he left that one of the steps Divine Mercy had to have in place that day was the necessity of my surviving my own suicide attempt a decade earlier.

During Lent last year, I wrote a post entitled, “Forty Days of Lent Without the Noonday Devil.” It featured a really terrific and monumentally helpful book by Catholic psychiatrist, Aaron Kheriaty, M.D. entitled, The Catholic Guide to Depression (Sophia Institute Press 2012). The book’s intriguing subtitle is “How the Saints, the Sacraments, and Psychiatry Can Help You Break Its Grip and Find Happiness Again.”

Dr. Kheriaty wrote something that I have come to know without doubt from personal experience. He wrote that in multiple studies in psychiatry, the one factor that Christianity, and especially Catholicism, lends to the prevention of suicide is the theological virtue of hope:

“The one factor most predictive of suicide was not how sick a person was, or how many symptoms he exhibited, or how much pain he or she was in. The most dangerous factor was a person’s sense of hopelessness. The patients who believed their situation was utterly without hope were the most likely candidates for completing suicide. There is no prescription or medical procedure for instilling hope. This is the domain of the revelation of God … the only hope that can sustain us is supernatural — the theological virtue of hope which can be infused only by God’s grace.” (pp. 98-99)

As an example of this virtue of hope, Dr. Kheriaty goes on to describe a practice that is at its essence. It is a practice that I learned from Saint Maximilian Kolbe who is here with me, and I today practice it to the best of my ability on a daily basis. Dr. Kheriaty writes that hope “unites us in a deeper way to Jesus Christ, allowing us to participate in his redemptive mission.” It is what Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI described in his Magisterial encyclical, Spe Salvi — Salvation and Hope — as suffering in union with Christ on the Cross:

“What does it mean to offer something up? Those who did so were convinced that they could insert these little [or big] annoyances into Christ’s great compassion so that they somehow became part of the treasury of compassion so greatly needed by the human race.”

— Spe Salvi, no. 40

It is from this treasury of compassion that the readers of Beyond These Stone Walls have offered prayers for me, that I may experience justice. You have met in a powerful way that urgent summons from the Gospel and Father Benedict Groeschel: “When I was in prison, you came to me.” You have brought hope to our prison door, and I thank you. I offer these days of unjust confinement for you. When a reader asks for my prayers in a comment or a letter, I choose a specific day in prison to offer for that person. I get the better end of the deal. Hope is precious, and fragile, and sometimes spread thin.

Father Benedict Groeschel gets the last word:

“On January 11, 2004, I was struck by a car and brought to the absolute edge of death. There is no real reason why I am alive, and there is no earthly reason why I am able to think and speak. I had no vital signs for 27 minutes, and no blood pressure. It’s amazing that not only did I survive but that I still have the use of mental equipment, which begins to deteriorate in three or four minutes without a blood supply… 50,000 people wrote e-mails promising prayers.”

— When Did We See You, Lord? pp. 123-124

“For you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God.”

— Colossians 3:3

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post in honor of our great good friend, Father Benedict Groeschel. You may like these related posts:

Father Benedict Groeschel at EWTN: Time for a Moment of Truth

How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night

With Padre Pio When the Worst that Could Happen Happens

To the Kingdom of Heaven through a Narrow Gate

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”