“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

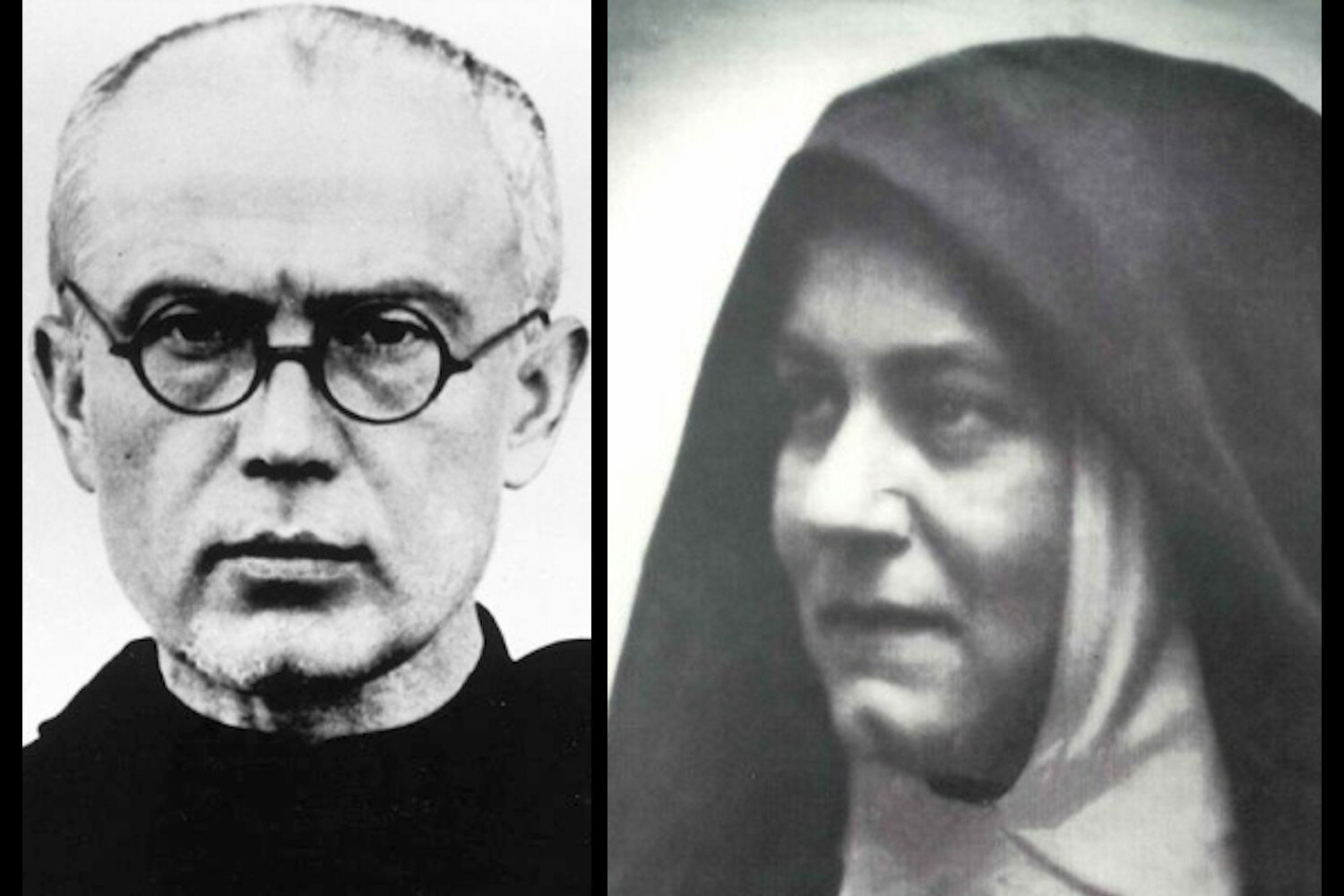

Saints and Sacrifices: Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein at Auschwitz

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross — Edith Stein — are honored this week as martyrs of charity and sacrifice.

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross — Edith Stein — are honored this week as martyrs of charity and sacrifice.

In a post some years ago I invited our readers to join my friend Pornchai Moontri and me in a personal Consecration to Saint Maximilian Kolbe’s dual movements: the Militia of the Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross. Our Consecration took place at Mass on the night of August 15, the Solemnity of the Assumption, and the day after Saint Maximilian’s Feast Day. Visit the website of the Militia of the Immaculata for instructions for enrolling in the Militia Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross.

We’re very moved by the number of people who have pledged to join us in this Consecration. The invitation remains always open.

Consecration as members of Saint Maximilian’s M.I. or Knights at the Foot of the Cross does not mean I plan to take on any more suffering or that I will never again complain. It does not even mean that I accept with open arms whatever crosses I bear and embrace them.

A person who is unjustly imprisoned must do all in his power to reverse that plight just as a person with cancer must do everything possible to be restored to health. Consecration does not mean we will simply acquiesce to suffering and look for more. It means we embrace the suffering of Christ, and offer our own as a share in it. In the end, I know I cannot empty myself, as Christ did, but I can perhaps attain the attitude of “Simon of Cyrene: Compelled to Carry the Cross,” of which my own is but a splinter.

I have written in the past that history has a tendency to treat its events lightly. The centuries have made Saint Patrick, for example, a sort of whimsical figure. History has distorted the fact that he became the saint he is after great personal suffering. Patrick was kidnapped by Irish raiders at the age of 16, forced from his home and family, taken across the Irish Sea and forced into slavery.

The life and death of Saint Maximilian are still too recent to be subjected to the colored glasses through which we often view history and sainthood. As with nearly all the saints — and with some of us who simply struggle to believe — great suffering was imposed on Maximilian Kolbe and he responded in a way that revealed a Christ-centered rather than self-centered life. What happened to Father Maximilian Kolbe must not be removed from what the Germans would call his “sitz im leben,” the “setting in life” of Auschwitz and the Holocaust. As evil as they were, they were the forges in which Maximilian cast off self and took on the person of Christ.

Scene from the 1978 mini-series “Holocaust”

“And the Winner Is . . .”

Do you remember the television “mini-series” productions of the 1970s and 1980s? After the great success of bringing Alex Haley’s “Roots” to the screen, several other forays into history were aired in our living rooms. One of them was a superb and compelling series entitled “Holocaust” that debuted on NBC on April 16, 1978. It was a brilliant and powerful example of television’s potential.

“Holocaust” won several Emmy Awards for NBC in 1978 for outstanding Limited Series, Best Director (Marvin Chomsky), Best Screenplay (Gerald Green), Best Actor (Michael Moriarty), Best Actress (Meryl Streep) and a number of Supporting Actor and other awards. As a historical narrative, however, “Holocaust” was deeply disturbing and shook an otherwise comfortable generation all too inclined to want to forget and move on. That was a complaint during the famous Nuremberg Trials of 1945 and 1946.

Just two years after the Allied Invasion of Germany and Poland ended the war and exposed the Death Camps, writers complained that Americans had lost interest and were not reading about the Nuremberg Trials. The aftermath of war revealed the sheer evil of the Nazi Final Solution, and it was more than most of us could bear to look at — so many did not look.

As I wrote in “Catholic Scandal and the Third Reich,” there are some who would have you believe that the Catholic Church is to be the moral scapegoat of the 20th Century. Viewing “Holocaust” (the miniseries) would quickly shatter any such revisionist history. Its first episode was so graphic in its depiction of Nazi oppression, and caused me so much anguish, that I struggled with whether to watch the rest.

I was 25 years old when it first aired, and finishing senior year at Saint Anselm College, a Benedictine school in New Hampshire. I was a double major in philosophy and psychology, and was in the middle of writing my psychology thesis on the relationship between trauma and depression when “Holocaust” kept me awake all night.

The morning after that first episode, I sought out a friend, an elderly Benedictine monk on campus who recommended the series to me. I thought he might tell me to turn my television off, but I was wrong. “This happened in my lifetime,” he said. “We cannot run from it. So don’t look away. Stare straight into its heart of darkness, and never forget what you see.”

He was right, and his words were eerily similar to those of biographer, George Weigel, who wrote of Pope John Paul II and his interest in Saint Maximilian Kolbe in Witness to Hope (HarperCollins, 1999):

Maximilian Kolbe . . . was the ‘saint of the abyss’ — the man who looked into the modern heart of darkness and remained faithful to Christ by sacrificing his life for another in the Auschwitz starvation bunker while helping his cellmates die with dignity and hope.

— Witness to Hope, p. 447

That was what the Holocaust was: “the modern heart of darkness.” I have been a student of the Holocaust since, but I am no closer to understanding it than I was on that sleepless night in 1978. As I asked in “Catholic Scandal and the Third Reich”:

“How did a society come to stand behind the hateful rhetoric of one man and his political machine? How did masses of people become convinced that any ideology of the state was worth the horror unfolding before their eyes?”

We have all been reading about the breakdown of faith in Europe, and about how decades-old scandals are now being used to justify the abandonment of Catholicism in European culture. This is not a new phenomenon. This madness engulfed Europe just eighty years ago, and before it was over, six million of our spiritual ancestors were deprived of liberty, and then life, for being Jews.

Hitler’s “Final Solution” exterminated fully two-thirds of the Jewish men, women, and children of Europe — and millions of others who either stood in his way or spoke the truth. Among those imprisoned and murdered were close to 12,000 Catholic priests and thousands more women religious and other Catholics. The determination to rid Europe of the Judeo-Christian faith did not begin with claims of sexual abuse, and this is not the first time such claims were used to further that agenda.

The Great Lie and Revealed Truth

This of all weeks keeps me riveted on the Holocaust. It was in this week that two of my dearest spiritual friends were murdered a year apart at Auschwitz by that madman, Hitler, and his monstrous Third Reich. Father Maximilian Kolbe traded his life for that of a fellow prisoner on August 14, 1941, and Edith Stein — who became Carmelite Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross — was dragged from a cattle train and murdered along with her sister, Rosa, immediately upon arrival at Auschwitz on August 9, 1942.

We must not forget this line from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (Vol. 1, Ch.10, 1925): “The great mass of people … will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one.” In order for a lie to disseminate and prevail, the truth must be controlled. In 1933, the Third Reich imposed the “Editor’s Law” in Germany requiring that editors and publishers join the Third Reich’s Literary Chamber or cease publishing. In 1933 there were over 400 Catholic newspapers and magazines published in Germany. By 1935 there were none.

The Nazi law was imposed in each country invaded by the Reich. In Poland, Father Maximilian was one of many priests sent to prison for his continued writings, but time in prison did not teach him the lesson intended by the Nazis. He was imprisoned again, and he would not emerge alive from his second sentence at Auschwitz. He was not alone in this. Nearly 12,000 priests were sent to their deaths in concentration camps.

“Come, Let Us Go For Our People.”

Edith Stein was the youngest of eleven children in a devout Jewish family in Germany. She was born on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, on October 12, l891. As a young woman, Edith broke her mother’s heart by abandoning her Jewish faith in adolescent rebellion. She was also brilliant, and it was difficult to win an argument with her using reason and logic. She was a master of both.

Edith received her doctorate in philosophy under the noted phenomenologist, Edmund Husserl, and taught at a German university when the Nazis came to power in 1933. During this time of upheaval, Edith converted to Catholicism after stumbling across the autobiography of Saint Teresa of Avila. “This is the truth,” Edith declared after reading it through in one sleepless night. A few years after her conversion, Edith Stein entered a Carmelite convent in Germany taking the name Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Blessed by the Cross).

March 27, 1939 was Passion Sunday, the beginning of Holy Week. In response to a declaration of Adolf Hitler that the Jews would bring about their own extinction, Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross wrote a private note to her Carmelite superior. She offered herself in prayer as expiation against the Anti-Christ who had cast all of Europe into a spiritual stranglehold. In her letter to her superior, Sister Teresa offered herself as expiation for the Church, for the Jews, for her native Germany, and for world peace.

As the Nazi horror overtook Europe, Sister Teresa grew fearful that she was placing her entire convent at risk because of her Jewish roots. Edith was then assigned to a Carmelite Convent in Holland. Her sister, Rosa, who also converted to Catholicism, joined her there as a postulant.

Catholics in France, Belgium, Holland and throughout Europe organized to rescue tens of thousands of Jewish children from deportation to the Death Camps. Philip Friedman, in Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust (The Jewish Publication Society, 1980) commended the Catholic bishops of the Netherlands for their public protest about the Nazi deportation of Jews from Holland. In retaliation for those bishops’ actions, however, even Jews who had converted to Catholicism were rounded up for deportation to Auschwitz.

A 2010 book by Paul Hamans — Edith Stein and Companions: On the Way to Auschwitz — details the horror of that day. Hundreds of Catholic Jews were arrested in Holland in retaliation for the bishops’ open rebellion, and most were never seen again. This information stands in stark contrast to the often heard revisionist history that Pope Pius XII “collaborated” with the Nazis through his “silence.” He was credited by the chief rabbi of Rome, Eugenio Zolli, with having personally saved over 860,000 Jews and preventing untold numbers of deaths.

The last words heard from Sister Teresa as she was forced aboard a cattle car packed with victims were spoken to her sister, Rosa, “Come, let us go for our people.” On August 9, 1942, Sister Teresa emerged from the cramped human horror of that cattle train into the Auschwitz Death Camp to face The Sorting.

Nobel Prize winner and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel described The Sorting:

“How do you describe the sorting out on arriving at Auschwitz, the separation of children who see a father or mother going away, never to be seen again? How do you express the dumb grief of a little girl and the endless lines of women, children and rabbis being driven across the Polish or Ukranian landscapes to their deaths? No, I can’t do it. And because I’m a writer and teacher, I don’t understand how Europe’s most cultured nation could have done that.”

That August 9th, Edith Stein went no further into the depths of Auschwitz than The Sorting. Some SS officer glared at this brilliant 50-year-old nun in the tattered remains of her Carmelite habit, and declared that she was not fit for work. This woman who had worked every day of her life, who taught philosophy to Germany’s graduate students, who scrubbed convent floors each night, was determined to be “unfit for work” by a Nazi officer who knew it was a death sentence.

Edith and Rosa were taken directly to a cottage along with 113 others, packed in, the doors sealed, and they were gassed to death. Their remains, like those of Maximilian Kolbe a year earlier, went unceremoniously up in smoke to drift through the sky above Auschwitz. And Europe thinks it would be better off now without faith!

“Thus the way from Bethlehem leads inevitably to Golgotha, from the crib to the Cross. (Simeon’s) prophecy announced the Passion, the fight between light and darkness that already showed itself before the crib … The star of Bethlehem shines in the night of sin. The shadow of the Cross falls on the light that shines from the crib. This light is extinguished in the darkness that is Good Friday, but it rises all the more brilliantly in the sun of grace on the morning of the Resurrection.

“The way of the incarnate Son of God leads through the Cross and Passion to the glory of the Resurrection. In His company the way of everyone of us, indeed of all humanity, leads through suffering and death to this same glorious goal.”

— Edith Stein/Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

The Exile of Father Dominic Menna and Transparency at The Boston Globe

As Father Dominic Menna, a senior priest at Saint Mary’s in Quincy, MA, was sent into exile, The Boston Globe’s role in the story of Catholic Scandal grew more transparent.

“I’m a true Catholic, and I think what these priests are doing is disgusting!” One day a few weeks ago, that piece of wisdom repeated every thirty minutes or so on New England Cable News, an around-the-clock news channel broadcast from Boston. I wonder how many people the reporter approached in front of Saint Mary’s Church in Quincy, Massachusetts before someone provided just the right sound bite to lead the rabid spectacle that keeps 24-hour news channels afloat.

The priest this hapless “true Catholic” deemed so disgusting is Father F. Dominic Menna, an exemplary priest who has been devoting his senior years in service to the people of God at Saint Mary’s. At the age of 80, Father Menna has been accused of sexual abuse of a minor.

There is indeed something disgusting in this account, but it likely is not Father Menna himself. He has never been accused before. Some of the news stories have not even bothered to mention that the claim just surfacing now for the first time is alleged to have occurred in 1959. No, I did not transpose any numbers. The sole accusation that just destroyed this 80-year-old priest’s good name is that he abused someone fifty-one years ago when he was 29 years old.

Kelly Lynch, a spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Boston, announced that Father Menna was placed on administrative leave, barred from offering the Sacraments, and ordered to pack up and leave the rectory where he had been spending his senior years in the company of other priests. These steps, we are told, are designed to protect children lest this 80-year-old priest — if indeed guilty — suddenly decides to repeat his misconduct every half century or so.

Ms. Lynch declined to reveal any further details citing, “the privacy of those involved.” That assurance of privacy is for everyone except Father Menna, of course, whose now tainted name was blasted throughout the New England news media last month. Among the details Kelly Lynch declines to reveal is the amount of any settlement demand for the claim.

Some of the fair-minded people who see through stories like this one often compare them with the 1692 Salem witch trials which took place just across Massachusetts Bay from Father Menna’s Quincy parish. The comparison falls short, however. No one in 1692 Salem ever had to defend against a claim of having bewitched a child fifty-one years earlier.

Archdiocesan spokesperson Kelly Lynch cited “the integrity of the investigation” as a reason not to comment further to The Boston Globe. Does some magical means exist in Boston to fairly and definitively investigate a fifty-one year old claim of child abuse? Is there truly some means by which the Archdiocese could deem such a claim credible or not?

Ms. Lynch should have chosen a word other than “integrity” to describe the “investigation” of Father Menna. Integrity is the one thing no one will find anywhere in this account — except perhaps in Father Menna himself if, by some special grace, he has not utterly lost all trust in the people of God he has served for over fifty years.

Transparency at The Boston Globe

The June 3rd edition of The Boston Globe buried a story on page A12 about the results of an eight-year investigation into the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. Eight years ago, it was front page news all over the U.S. that the Los Angeles Archdiocese was being investigated for a conspiracy to cover-up sexual abuse claims against priests.

After eight years of investigation at taxpayer expense, California prosecutors reluctantly announced last month that they have found insufficient evidence to support the charges. That news story was so obviously buried in the back pages of The Boston Globe that the agenda could not be more transparent. The story of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church is front page news only when it accommodates the newspaper’s editorial bias. That much, at least, is clear.

But all transparency ends right there. The Globe article attributed the lack of evidence of a conspiracy by Catholic bishops to the investigation being “stymied by reluctant victims.” Now, that’s an interesting piece of news!

The obvious question it raises is whether these claimants were reluctant to speak BEFORE obtaining financial settlements in their claims against the Archdiocese. If they are reluctant witnesses now, then, at best, it may be because the true goal of some has long since been realized and there is nothing in it for them to keep talking. At worst, the silence of claimants in the conspiracy investigation could be interpreted as an effort to fend off pointed questions about their claims. Perhaps prosecutors were investigating the wrong people.

I have seen this sort of thing play out before. Last year, a New Hampshire contingency lawyer brought forward his fifth round of mediated settlement demands against the Diocese of Manchester. During that lawyer’s first round of mediated settlements in 2002 — in which 28 priests of the Diocese of Manchester were accused in claims dating from the 1950s to the 1980s — the news media announced a $5.5 million settlement. The claimants’ lawyer was astonished that $5.5 million was handed over with no real effort at proof or corroboration sought by Diocesan representatives before they paid up and deemed the claims “credible.” The lawyer was quoted in the news media:

“During settlement negotiations, diocesan officials did not press for details such as dates and allegations for every claim. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“He and his clients did not encounter resistance from the Diocese of Manchester in their six months of negotiations. Some victims made claims in the last month, and because of the timing of negotiations, gained closure in just a matter of days.”

That lawyer’s contingency fee for the first of many rounds of mediated settlements was estimated to be in excess of $1.8 million. When the mediation concluded, the news media reported that at the attorney’s and his clients’ request, the diocese agreed not to disclose the claimants’ names or any details of their claims or the amounts they received in settlement. “No confidentiality was sought by the Diocese,” the lawyer declared.

In contrast, the names of the accused priests — many of whom were deceased and none of whom faced criminal charges — were repeatedly released and publicized throughout the news media. This process served one purpose: to invite new claimants against those same priests with assurances that their names would remain private and no real corroborating details would ever be elicited. It was clear that non-disclosure clauses were demanded by the contingency lawyer and his clients, though the diocese and its lawyers were eager to oblige as part of the settlement.

It is fascinating that the news media now blames “reluctant victims” for stifling an investigation into cover-ups in the Catholic Church. That is a scandal worthy of the front page, but we won’t ever see it there. If the news media now has concerns about the very people whose cause it championed in 2002, we won’t be reading about it in the news media. Transparency in the news media, after all, is a murky affair.

Transparency and the U.S. Bishops

Writer Ryan A. MacDonald has a number of contributions published on These Stone Walls. His most recent is, “Should the Case Against Father Gordon MacRae Be Reviewed?” I am told that Mr. MacDonald has an essay published in the June/July, 2010 issue of Homiletic & Pastoral Review entitled, ”Anti-Catholicism and Sex Abuse.” In the essay, the writer also recommends These Stone Walls to H&PR readers. Though I subscribe to the well respected H&PR, I have not at this writing seen the current issue.

Ryan MacDonald also has a letter published in a recent issue of Our Sunday Visitor (“Raising the Alarm,” June 13, 2010). Ryan makes a point very similar to one I made last month in “As the Year of the Priest Ends, Are Civil Liberties for Priests Intact?” Here is an excerpt from Ryan’s OSV letter:

“A number of courageous bishops have argued in opposition to retroactive application of revised civil statutes of limitations. Such revised statutes typically expose the Catholic Church to special liability while exempting public institutions.

“But I must raise the alarm here. As a body, American bishops lobbied the Holy See for retroactive extension of the time limits of prescription, the period of time in which a delict (a crime) exists and can be prosecuted under Church law …

“… Many accused priests now face the possibility of forced laicization with no opportunity for defense or appeal because our bishops have embraced routine dispensation from the Church’s own statute of limitations. The bishops cannot argue this point from two directions. Some have defended this duplicity citing that the delicts involve criminal and not civil matters. This is so, but these men are also American citizens, and the U.S. Constitution prohibits retroactive application of criminal laws as unconstitutional.

“Statutes of limitations exist in legal systems to promote justice, not hinder it. Our bishops cannot have it both ways on this issue.”

Ryan MacDonald made this point far better than I ever could. The issue for me is not just the obvious double standard applied when the spirit of Church law is set aside. The issue is one of fundamental justice and fairness, and what Cardinal Dulles called “The great scandal of the Church’s failure to support Her priests in their time of need.” Pope John Paul II said that the Church must be a mirror of justice. Let’s hope our bishops can respond to the public scandal of sexual abuse without perpetrating a private scandal of their own.

There are people in groups like S.N.A.P. and Voice of the Faithful who clamor for the Church to ignore the rights of priests in favor of an open embrace of “survivors.” It is always easy to deny someone else’s rights and restrict someone else’s civil liberties, and that, historically, is how witch hunts begin.

+ + +

“A Day Without Yesterday:” Father Georges Lemaitre and The Big Bang

The Catholic Church in Belgium can take pride in the story of Georges Lemaitre, the priest and mathematician who changed the mind of Einstein on the creation of The Universe.

The Catholic Church in Belgium can take pride in the story of Georges Lemaitre, the priest and mathematician who changed the mind of Einstein on the creation of The Universe.

(This post needs a disclaimer, so here it is. It’s a post about science and one of its heroes. It’s a story I can’t tell without a heavy dose of science, so please bear with me. I read the post to my friends Pornchai, Joseph, and Skooter. Pornchai loved the math parts. Joseph said it was “very interesting,” and Skooter yawned and said, “You CAN’T print this.” When I told Charlene about the post, she said, “Well, people may never read your blog again.” Well, I sure hope that’s not the case. I happen to think this is a really cool story, so please indulge me these few minutes of science and history.)

The late Carl Sagan was a professor of astronomy at Cornell University when he wrote his 1980 book, Cosmos. It spent 77 weeks on the New York Times Best Seller List. Later in the 1980s, Dr. Sagan narrated a popular PBS series also called “Cosmos,” based on his book. Sagan was much imitated for his monotone intonation of “BILLions and BILLions of stars.” I taped all the installments of “Cosmos,” and watched each at least twice.

More than once, I fell asleep listening to Sagan’s monotone “BILLions and BILLions of stars.” I hope you’re not doing the same right now. Science was my first love as a geeky young man. Religion and faith eventually overtook it, but science never left me. Astronomy has been a lifelong fascination, and Carl Sagan was one of its icons. That’s why I was enthralled 25 years ago to walk out of a bookstore with my reserve copy of Sagan’s first and only novel, Contact (Simon & Shuster, 1985).

Contact was about radio astronomy and the SETI project — the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence. It wasn’t science fiction in the way “Star Trek” was science fiction. Contact was science AND fiction, a novel crafted with real science, and no one but Carl Sagan could have pulled it off. The sheer vastness of the Cosmos unfolded with crystal clarity in Sagan’s prose, a vastness the human mind can have difficulty fathoming. Anyone who thinks we are visited by aliens from other planets doesn’t understand the vastness of it all.

The central theme of Contact was the challenge astronomy poses to religion. In the story, SETI scientist Eleanor Arroway — a wonderful character portrayed in the film version by actress Jodie Foster — becomes the first radio astronomer to detect a signal emitting from another civilization. The signal came from a planet orbiting Vega, a star, not unlike our own, about 26 light years from Earth. The message of the book (and film) is clear: if another species like us exists, and we are ever to have contact, it will be in just this way — via radio waves moving through space at light speed.

Here comes the geeky part. For those who never caught the science bug, a “light year” is a unit of distance, not time. Light moves through space at a known rate of speed — about 186,000 miles per second. At that rate, light travels through space about 5.86 trillion miles in one year. That’s a “light year,” and in numbers it represents 5,860,000,000,000 miles. In the vacuum of space, radio waves also travel at the speed of light.

The galaxy in which we live — the one we call “The Milky Way” — is a more or less flat spiral disk comprised of about 100 billion stars. The Milky Way measures about 100,000 light years across. That’s a span of about 6,000,000,000,000,000,000 miles, give or take a few. Please don’t ask me to convert this to kilometers!

This means that light — or radio waves — from across our galaxy can take up to 100,000 years to reach Earth. One of The Milky Way Galaxy’s approximately 100 billion stars is shining in my cell window at this moment. Our galaxy is one of about fifty billion galaxies now known to comprise The Universe. The largest known to us is thirteen times larger than The Milky Way. You get the picture. The Universe is immense.

If E.T. Phones Home, Make Sure It’s Collect!

In a recent post I made a cynical comment about UFOs. I wrote, “The real proof of intelligent life in The Universe is that they don’t come here.” It was an attempt at humor, but the problem with searching for extraterrestrial intelligence is one of practical physics. The limit of our ability to “listen” is a mere few hundred light years from Earth, a tiny fraction of the galaxy — a mere survey of our own backyard. If there is another civilization out there, we may never know it.

Even if we hear from them some day, it will be a one-sided conversation. The signal we may one day receive might have been broadcast hundreds — perhaps thousands — of years earlier. If we respond, it will take hundreds or thousands of years for our response to be detected. We sure won’t be trading recipes, or asking, “What’s new?” If there’s anyone out there — and so far we know of no one else — we can forget about any exchange of ideas, let alone ambassadors.

Still, I devoured Contact twice in 1985, then I wrote Carl Sagan a letter at Cornell. I understood that Sagan was an atheist, but the central story line of Contact was the effect the discovery of life elsewhere might have on religion, especially on fundamentalist Protestant sects who seemed the most threatened by the discovery.

I thought Carl Sagan handled the controversy quite well, without judgments, and even with some respect for the religious figures among his characters. In my letter, I pointed out to Dr. Sagan that Catholicism, the largest denomination of Christians in America, would not necessarily share in the anxiety such a discovery would bring to some other faiths. I wrote that if our galactic neighbors were embodied souls, like us, then they would be in need of redemption in the same manner in which we have been redeemed.

Weeks later, when an envelope from Cornell University’s Department of Astronomy and Space Sciences arrived, I was so excited my heart was beating BILLions and BILLions of times! Carl Sagan was most gracious. He wrote that my comments were very meaningful to him, and he added, “You write in the spirit of Georges Lemaitre!”

I framed that letter and put it on my rectory office wall. I wanted everyone I knew to see that Carl Sagan compared me with Georges Lemaitre! I was profoundly moved. But no one I knew had a clue who Georges Lemaitre was. I must remedy that. He was one of the enduring heroes of my life and priesthood. He still is!

Father of the Big Bang

Georges Lemaitre died on June 20, 1966 when I was 13 years old. It was the year “Star Trek” debuted on network television and I was mesmerized by space and the prospect of space travel. Georges Lemaitre was a Belgian scientist and mathematician, a pioneer in astrophysics, and the originator of what became known in science as “The Big Bang” theory — which, by the way, is no longer considered in cosmology to be a theory.

But first and foremost, Father Lemaitre was a Catholic priest. He was ordained in 1923 after earning doctorates in mathematics and science. Father Lemaitre studied Einstein’s celebrated general theory of relativity at Cambridge University, but was troubled by Einstein’s model of an always-existing, never changing universe. It was that model, widely accepted in science, that developed a wide chasm between science and the Judeo-Christian understanding of Creation. Einstein and others came to hold that The Universe had no beginning and no end, and therefore the word “Creation” could not apply.

Father Lemaitre saw problems with Einstein’s “Steady State” theory, and what Einstein called “The Cosmological Constant” in which he maintained that The Universe was relatively unchanging over time. From his chair in science at Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium from 1925 to 1931, Father Lemaitre put his formidable mind to work.

He developed both a mathematical equation and a scientific basis for what he termed the “primeval atom,” a sort of cosmic egg from which The Universe was created. He also concluded that The Universe is not static, as Einstein believed, but expanding at an ever increasing rate, and he put forward a mathematical model to prove it. In 1998, Father Lemaitre was proven to be correct.

Einstein publicly disagreed with Lemaitre’s conclusions, and the priest was not taken seriously by mainstream science largely because of that. In his book, The Universe in a Nutshell (Bantam Books, 2001), mathematician and physicist Stephen Hawking addressed the controversy:

“If galaxies are moving apart now, it means they must have been closer together in the past. About fifteen billion years ago, they would have been on top of each other, and the density would have been very large. This state was called the “primeval atom” by the Catholic priest Georges Lemaitre, who was the first to investigate the origin of the universe that we call the big bang. Einstein seems never to have taken the big bang seriously”

Stephen Hawking actually calculated the density of Father Lemaitre’s “Primeval Atom” just prior to The Big Bang. It was 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, tons per square inch. I haven’t checked this math myself, so we’ll take Professor Hawking’s word for it.

Though Einstein disagreed with Father Lemaitre at first, he respected his brilliant mathematical mind. When Einstein presented his theories to a packed audience of scientists in Brussels in 1933, he was asked if he thought his ideas were understood by everyone present. “By Professor D, perhaps,” Einstein replied, “And certainly by Lemaitre, as for the rest, I don’t think so.”

When Father Lemaitre presented his concepts of the “primeval atom” and an expanding universe, Einstein told him, “Your mathematics is perfect, but your grasp of physics is abominable.”

They were words Einstein would one day have to take back. When Edwin Hubble and other astronomers read Father Lemaitre’s paper, they became convinced that it was Einstein’s physics that was flawed. They could only conclude that the priest and scientist was correct about the creation and expansion of The Universe from the “primeval atom,” and the fact that time, space and matter actually did begin at a moment of creation, and that The Universe will end.

It’s an ironic twist that science often accuses religion of holding back the truth about science. In the case of Father Lemaitre and The Big Bang, it was science that refused to believe the evident truth that a Catholic priest proposed to a mathematical certainty: that the true origin of The Universe, and of time and space, is its creation on “a day without yesterday.”

For his work, Father Lemaitre was inducted into the Royal Academy of Belgium, and was awarded the Franqui prize by an international commission of scientists. Pope Pius XI applauded Father Lemaitre’s view of the creation of the universe and appointed him to the Pontifical Academy of Science. Later, Pope Pius XII declared that Father Lemaitre’s work was a vindication of the Biblical account of creation.

The Pope saw in Father Lemaitre’s brilliance a scientific model of a created Universe that bridged science and faith and halted the growing sense that each must entirely reject the other.

Einstein finally came around to endorse, if not openly embrace Father Lemaitre’s conclusions. He admitted that his concept of an eternal, unchanging universe was an error. “The Cosmological Constant was my greatest mistake,” he said.

In January, 1933, Father Georges Lemaitre traveled to California to present a series of seminars. When Father Lemaitre finished his lecture on the nature and origin of The Universe, a man in the back stood and applauded, and said, “This is the most beautiful and satisfying explanation of creation to which I have ever listened.” Everyone present knew that voice. It was Albert Einstein, and he actually said the “C” word so disdained by the science of his time: “Creation!”

“I want to know how God created this world. I am not interested in this or that phenomenon, in the spectrum of this or that element. I want to know God’s thoughts; the rest are details.”

“The more we know of the universe, the more profoundly we are struck by a Reason whose ways we can only contemplate with astonishment” … Albert Einstein once said that in the laws of nature, ‘there is revealed such a superior Reason that everything significant which has arisen out of human thought and arrangement is, in comparison with it, the merest empty reflection.’ In what is most vast, in the world of heavenly bodies, we see revealed a powerful Reason that holds the world together.”

“In the Beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters.”

“Live long and prosper.”

For Further Reading:

Catholic Scandal and The Third Reich: The Rise and Fall of a Moral Panic

.“The great mass of people … will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one.” Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Vol. 1, Ch. 10 (1925)

“The great mass of people … will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one.” Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, Vol. 1, Ch. 10 (1925)

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a tribute to Saint Maximilian Kolbe on the April 28th anniversary of his ordination. I made a controversial point in that post:

“Almost without exception, the typical claims of abuse by Catholic priests so roiling the news media were alleged to have happened thirty to forty years ago.”

Go back just another thirty to forty years, I wrote, and you will find yourself right in the middle of the Nazi horror that engulfed Europe and claimed the lives of six million Jews and millions of others. I suggested that Catholics should not accept what some would now impose: that the Catholic Church is to be the moral scapegoat of the Twentieth Century.

A TSW reader responded to that insight by sending me a rather startling document. As I began to read it, I almost tossed it aside dismissing it as just another sensational headline. You might be tempted to do the same. Resist that temptation, please, and keep reading:

“There are cases of sexual abuse that come to light every day against a large number of the Catholic clergy. Unfortunately it’s not a matter of individual cases, but a collective moral crisis that perhaps the cultural history of humanity has never before known with such a frightening and disconcerting dimension. Numerous priests and religious have confessed. There’s no doubt that the thousands of cases which have come to the attention of the justice system represent only a small fraction of the true total, given that many molesters have been covered and hidden by the hierarchy.”

This isn’t an editorial in yesterday’s New York Times, nor is it the opening gun in a new lawsuit by Jeffrey Anderson. It also isn’t a quote from S.N.A.P. or V.O.T. F. It is part of a speech delivered on May 28, 1937 by Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda for the Third Reich.

As a direct result of Goebbels’ speech, 325 Catholic priests representing every diocese in Germany were arrested and sent to prison. The story was uncovered by Italian sociologist and author, Massimo Introvigne and republished by LifeSiteNews.com. According to Mr. Introvigne, the term “moral panic” is a modern term used since the 1970s “to identify a social alarm created artificially by amplifying real facts and exaggerating their numbers” and by “presenting as ‘new’ events which in reality are already known and which date to the past.”

It all has a terribly familiar ring. Though “moral panic” wasn’t a term used in 1937, it describes exactly what Joseph Goebbels was called upon by the Third Reich to create. And the propaganda campaign, like the current one, had nothing to do with protecting children. It was launched by the Third Reich because of a 1937 Papal Encyclical by Pope Pius XI entitled “Mit brennender Sorge” — “With burning concern” — in which the Pope condemned Nazi ideology. According to Matthew Cullinan Hoffman of lifeSiteNews.com, the encyclical was smuggled out of Rome into Germany and read from every pulpit in every Catholic parish in the Reich.

The propaganda campaign launched by Goebbels was later exposed as a clear exaggeration and exploitation of a few cases of sexual abuse that were all too real, but for which the Church had taken decisive action. In the end, the vast majority of the priests arrested and imprisoned, their reputations destroyed and the Church’s moral authority in Germany impugned — were quietly set free. When the campaign finally evaporated, only six percent of the 325 priests accused were ultimately condemned, and it is a certainty that among even those were some who were falsely accused.

By the end of the war, according to Introvigne, “the perfidy of the campaign of Goebbels aroused more indignation than the eventual guilt” of a relatively small number of priests — a number that was a mere percentage of those first accused.

The accused priests were not Goebbels’ real target, of course. The Nazi Ministry of Propaganda targeted the Church and its bishops and papacy declaring a cover-up of the claims and keeping the matter in the daily headlines.

According to Massimo Introvigne who uncovered this story, “Goebbels’ campaign followed the same pattern seen in recent media attacks on the Church.” Like today’s moral panic, the Goebbels campaign attempted to revive old claims that had long since been resolved to keep the matter in public view and to discredit the Catholic Church.

It was all because of the Papal encyclical denouncing Nazi ideology and tactics and defending “the Church’s Jewish heritage against Hitler’s racist attacks,” according to Hoffman.

Consider the Source

How the Massimo Introvigne article came to me makes for an interesting aside. It was sent to me by a victim of sexual abuse perpetrated twenty-two years ago by a priest in my diocese, a priest with whom I once served in ministry. The young man he violated has worked to overcome his anger and to embrace the grace of forgiveness. He sought and obtained a modest settlement for the abuse he suffered years ago, and he used it for counseling expenses. This man is a reader of These Stone Walls who recently wrote to me:

“I have been scouring the Internet and doing a great deal of reading … For what it is worth, I believe you are serving an unjust sentence for a crime you did not commit. If I do not do everything in my power to be of assistance to you, I would be committing a grave sin.”

That is certainly a far different reaction than the rhetoric of most other claimants against priests and their “advocates” among contingency lawyers and the victim groups that are receiving major donations from contingency lawyers. My more recent exchanges with this man lead me to conclude something I have long believed: that the people most repulsed and offended by false claims of abuse and the rhetoric of a witch hunt should be the real victims of sexual abuse.

It is no longer the Nazi state that stands to win big from the creation of a moral panic targeting the Catholic Church and priesthood. But the current propaganda campaign is little different in either its impetus or its result.

Dr. Thomas Plante, Ph.D., a professor of Psychology at Santa Clara University, published an article entitled “Six important points you don’t hear about regarding clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church” (Psychology Today, March 24, 2010). Dr. Plante’s conclusions from studying the empirical data are far different from what you may read in any propaganda campaign — either the 1937 one or the one underway now. These are Dr. Plante’s conclusions:

“Catholic clergy are not more likely to abuse children than other clergy or men in general.” [As I pointed out in “Due Process for Accused Priests,” priests convicted of sexual abuse account for no more than three (3) out of 6,000 incarcerated, paroled, and registered sex offenders.]

“Clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic church cannot be blamed on celibacy.” The majority of men convicted of sexual abuse are married and/or divorced.

“Almost all of the clergy sexual abuse cases that we hear about in the news are from decades ago,” most from the 1960s to 1970s.

“Most clergy sex offenders are not pedophiles.” Eighty percent of accusers were post-pubescent teens, and not children, when abuse was alleged to have occurred.”

“There is much to be angry about,” Dr. Plante concluded, but anger about the above media-fueled misconceptions is misplaced. Why this isn’t clearer in the secular press is no mystery? As one observer of the news media wrote,

“More than illness or death, the American journalist fears standing alone against the whim of his owners or the prejudice of his audience.”

— Lewis Lapham, Money and Class in America, Ch. 9, (1988)

You know I was born on April 9, 1953. That was just eight years to the day after Lutheran theologian and pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer was hanged at age 39 on the direct orders of Adolf Hitler. It was to be Hitler’s last gesture of contempt for truth before he took his own life as the Allies advanced on Germany in April, 1945.

Since childhood, I have been aware that I shared this date with Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a man I greatly admire. He was imprisoned and hanged because he made a decision of conscience to resist Hitler with every ounce of strength God gave him. I concluded my Holy Week post with an excerpt of his most famous book, The Cost of Discipleship.

The truth of what happened in Germany and Poland emerged into full public view just sixty-five years ago. The entire world recoiled in horror and revulsion. The revelations changed the world, radically altering humanity’s world view. It marked the dawn of the age of cynicism and distrust. How did a society come to stand behind the hateful rhetoric of one man and his political machine? How did masses of people become convinced that any ideology of the state was worth the horror unfolding before their eyes?

As the truth slowly emerged during the years of war and slaughter, The New York Times, in its 1942 Christmas Day editorial declared:

“No Christmas sermon reaches a larger congregation than the message Pope Pius XII addresses to a war-torn world at this season. This Christmas more than ever he is a lonely voice crying out of the silence of a continent.”

In 1942, The New York Times was joined in its acclaim of Pope Pius XII by the World Jewish Congress, Albert Einstein, and Golda Meir. The March 2010 issue of Catalyst reported that Pope Pius was officially recognized for directly saving the lives of 860,000 Jews while the chief rabbi in Rome, Eugenio Zolli, converted to Catholicism and took the name “Eugenio” in honor of the Pope’s (Eugenio Pacelli) challenge of the Nazi regime.

The New York Times has sure changed its tune since then, and has helped build a revisionist history of Pope Pius XII and the Catholic Church that takes a polar opposite point of view. Today, commending a pope, or even mentioning Christmas, would be anathema to the Times’ editorial agenda.

By the end of April, 1945, within days of ordering Dietrich Bonhoeffer hanged, Adolf Hitler took his own life. Joseph Goebbels, intensely loyal to Hitler, murdered his wife and children before also committing suicide. The terror and propaganda of the Third Reich were over.

The propaganda of the current moral panic is just getting fully underway, however. British atheist Richard Dawkins has declared the Catholic Church to be “a child-raping institution” and wrote in The Washington Post a few weeks ago of Pope Benedict’s planned visit to England in September:

“This former head of the Inquisition should be arrested the moment he dares set foot outside the tin pot fiefdom of the Vatican and he should be tried in an appropriate civil court.”

Does this sound like reasonable discourse to you? And it isn’t just the secular press engaged in this sort of hate speech. I was utterly dismayed a few weeks ago to see a highly respected Catholic weekly newspaper box off and highlight a letter from a reader calling for the imprisonment of all priests accused from thirty and forty years ago.

Don’t be so quick to consign 80-year-old men to prison for things alleged to have happened decades ago — things that cannot be proven at all. It’s tempting to toss the rights of all priests out the window in the heat of a global media witch trial, but it is not the way of our Church to abandon all reason in favor of the mob.

The secular press is going to do what it always does: sell newspapers to the mob. But this hateful rhetoric should not be appearing in the Catholic press. Calling upon the Vatican to set aside the rights of priests under Church law is no way to conclude the Year of the Priest.

Adopting the rhetoric of Joseph Goebbels simply doesn’t bring light to the issues. It is caving in to our basest nature, and reflects not the Truth upon which our faith is built. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran, would be calling Catholics to a much higher standard of discipleship.

Pope Pius XI denounced the Nazi ideology in his 1937 Encyclical "Mit bennender Sorge."

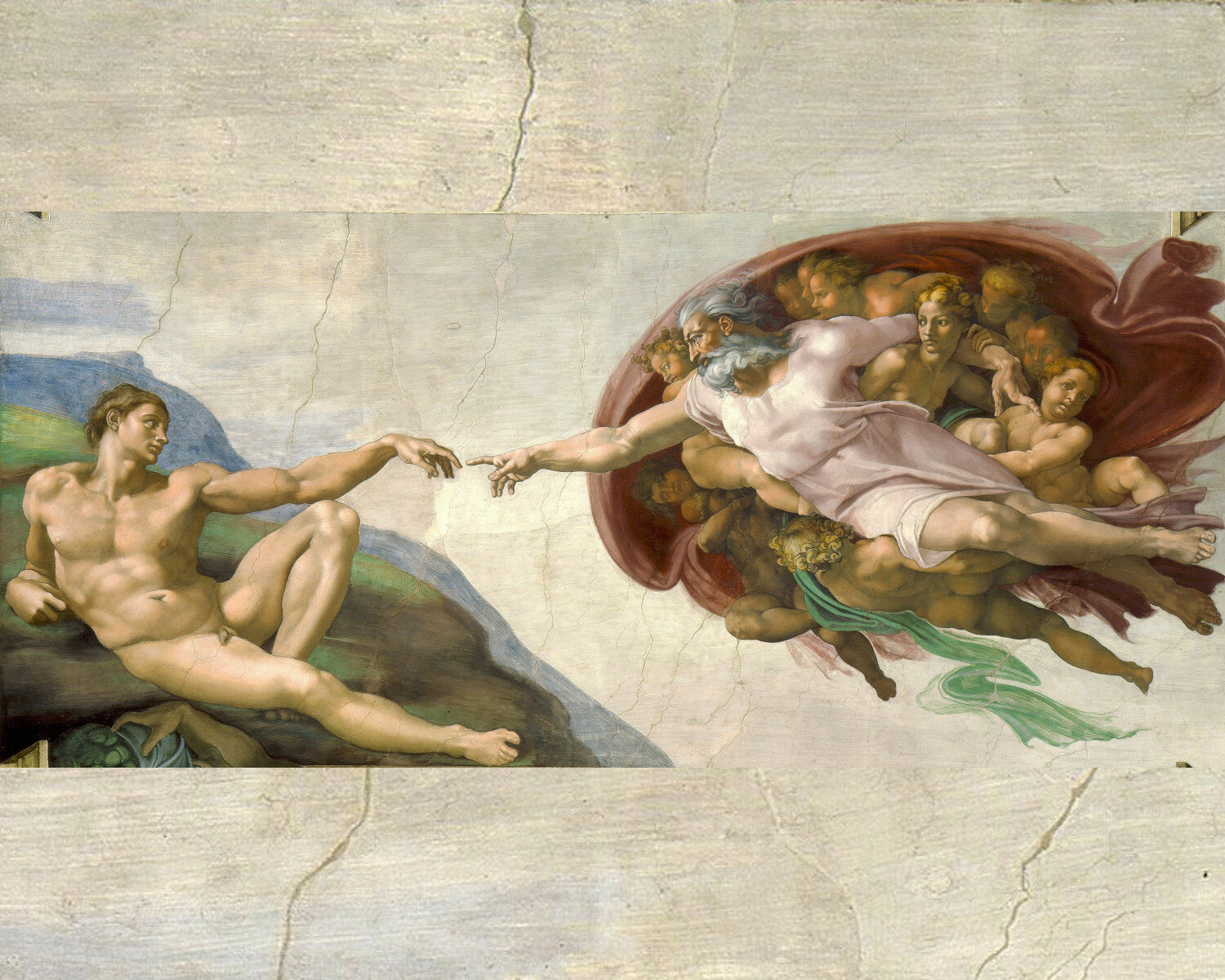

Michelangelo and the Hand of God: Scandal at the Vatican

Seen with the eyes of any faith at all, this story leaves you wondering just how the hand of God is writing your own history. The story is true, and it’s fascinating.

Seen with the eyes of any faith at all, this story leaves you wondering just how the hand of God is writing your own history. The story is true, and it’s fascinating.

“Calendar with frontal nudity – Not Allowed.” I received that notice from the prison mail room several years ago instructing me that I had two choices: have the pornographic contraband destroyed or sent out. I had no idea what it was, but the sender was my younger brother, Scott. I was furious with Scott. I thought his judgment had fallen off a cliff somewhere and he tried to send me a Playboy calendar — or worse. “He should know better!” I thought. “What on earth would make him think I would want a nude calendar?”

The next day I received a letter from Scott: “I hope you like the calendar!” he wrote. That confirmed it! My brother had gone mad! When I finally reached him by telephone, he told me that the calendar was entitled “Vatican City: Scenes from the Sistine Chapel.”

I never did get to see the calendar. I had it returned to my brother with an apology from me for thinking he had lost his marbles. I’m not sure at what point Michelangelo’s work became pornography. It’s a recent phenomenon, but not necessarily a new one. In Witness to Hope, his famed biography of Pope John Paul II, George Weigel described the Holy Father’s insistence that Michelangelo’s work be restored to its original design:

“In addition to authorizing the restoration of the frescoes . . . John Paul made sure, when it came time to clean the Last Judgment, that the restorers removed about half the leggings, breechcloths, and other drapings with which prudish churchmen had hidden Michelangelo’s nudes, years after the masterpiece had been completed.”

In the years before I was accused and sent to prison ( see the About Page), I had a beautiful framed reproduction of Michelangelo’s famed “Creation of Adam,” one of the magnificent frescoes he painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel between 1508 and 1512. It’s an image that just about every one of the world’s one billion Catholics has seen whether they have visited the Eternal City or not. A few years ago, a priest in Ottawa sent me a card bearing a part of that same image, the hand of God reaching toward the hand of Adam to bestow life. It was on my cell wall for two years before it disappeared one day when I was moved from place to place.

When things aren’t “Going My Way” — which you know is often if you’ve been reading my posts — I sometimes drift into thinking that God’s hand in history is an illusion. Then I come across stories like the one I’m about to tell you — the story of how Michelangelo came to paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

HOLD ON! Don’t go just yet! I promise not to write a history lesson every week, but this is one of the strangest stories I have ever encountered, and I just have to write about it. So bear with me, please, as I again meander down that path. Seen with the eyes of any faith at all, this story leaves you wondering just how the hand of God is writing your own history. The story is true, and it’s fascinating.

The Poseidon Adventure

In Greek mythology, Laocoön was a priest of the Roman god of the sea, Neptune. He tried to dissuade the leaders of Troy from bringing the famed Trojan Horse into the city.

“What madness, citizens, is this? Have you not learned enough of Grecian fraud to be on your guard against it? For my part, I fear the Greeks even when they bear gifts.”

In the mythological story, Poseidon, the Greek version of Neptune, became angry at the Trojans and sent sea serpents to kill Laocoön and his sons just as he tried to convince the Trojans not to bring the horse through the city gates. As the Trojans witnessed the death of Laocoön, they took it as a sign not to heed his advice. They brought the Trojan Horse inside the city walls to their peril. You know the rest.

In 38 B.C., on the Island of Rhodes off the coast of Turkey, three Greek sculptors created The Laocoön, a magnificent freestanding marble sculpture depicting the attack of Poseidon’s serpents upon the priest and his sons. It was the world’s most famous sculpture, and the best known example of ancient Hellenistic art known to exist at that time. Over centuries, The Laocoön became legendary. Then it became lost. With one city state sacking another, the magnificent Laocoön faded from history, and its very existence became a legend. Pliny wrote of having seen it, and described its every detail in the late first century, A.D. By the time of Michelangelo 1500 years later, every sculptor knew the legend of The Laocoön, but it had been many centuries since anyone had seen it.

When in Rome

In 1505, 30-year-old Michelangelo Buonarroti was commissioned to create life-size free standing marble sculptures of each of the Twelve Apostles for the Cathedral at Florence. It was an extremely ambitious plan that he doubted he could complete in his lifetime. Michelangelo began his work on a life size sculpture of St. Matthew, the first of the immense project.

Just after beginning, however, Michelangelo was summoned to Rome by Pope Julius II. In a game of one-up-manship typical of the time, the Pope usurped the Florence project by ordering Michelangelo to stay in Rome and create a marble tomb that would immortalize the pope. It was originally intended to be the most ambitious monument the world had ever seen, comprising forty life-sized marble sculptures. Under duress, Michelangelo began sketching out this folly.

Scandal Time — The Prequel

What was going on in the Catholic Church parallel to all this is an eye-opener. Over a roughly sixty year period from 1470 to 1530, a succession of popes became embroiled in the labyrinthine temporal politics of the reigning princes and kings of the Italian city-states. It was all, to say the least, colorful and overtly scandalous. If you ever feared the Church may not endure the scandals of our day, think again! They are as nothing next to what went on in Rome five centuries ago.

Pope Julius II reigned for a decade from 1503 to 1513. History considers him one of the more brilliant and just of the Renaissance popes, yet he was suspected of having bribed his way into the papacy. His chief concern as pope was to expand the Papal States to compete more effectively — some would say more ruthlessly — among the city-state model of government in place at the time.

The principal fault of popes in the Renaissance period was their unbridled capitulation to the agendas and values of the secular world, and it led to schism — to the Protestant Reformation which turned out to be anything but a reform. Removing all central teaching authority from their churches caused dissension and divisions splitting them into hundreds of sects. Those divisions continue today.

It’s an ironic twist of history that many of those who hold the Catholic Church in contempt for caving in to secularism in the 16th Century also demand that the Church repeat the mistake in the 21st Century. In Connecticut last year, legislation was proposed to strip the Catholic Church of authority over Catholic parishes in that state. Its major proponents were largely members of Voice of the Faithful whose motto is “Keep the Faith; change the Church.” Those who do not understand history are doomed to repeat it.

Digging Up The Past

Back to Michelangelo. Just months into his conscripted labor on the Pope’s personal tomb, Michelangelo dismayed of ever completing it, and decided to flee from Rome to return to Florence against the Pope’s wishes. Pope Julius was long on ego and short on funds. He dedicated most of the funds available to the restoration of St. Peter’s Basilica and the architectural marvel that is the centerpiece of our Church today. The Pope’s unfunded ambition for his 40-sculpture personal tomb left Michelangelo in near despair.

This is where the story gets bizarre. Just as Michelangelo prepared to leave Rome in 1506, however, he visited the home of a friend who happened to be the son of Guiliano de Sangallo, the chief architect for Pope Julius’s renovation and enlargement of St. Peter’s Basilica. As Michelangelo visited his friend, a messenger came charging in.

On that same day in Rome in 1506, landowner Felice di Fredi was clearing his vineyards of large stones. He had no idea — or at least no appreciation — that the stones were the remnants of ancient walls that once surrounded the golden home of Emperor Nero.

“CLUNK!” Fredi’s shovel struck something large, white, and very hard. In four large sections, he dug up a large marble structure. Someone sent word to the papal architect, Guiliano de Sangallo, who set out on horseback accompanied by his son and their guest, Michelangelo to assess the unearthed marble treasure.

Upon arrival, the elder de Sangallo took one look at the sculpture and exclaimed: “It’s The Laocoön that Pliny describes!” Out of long buried history, the world’s oldest and most famous freestanding marble sculpture arrived at the Vatican to cheers and applause accompanied by Michelangelo himself, the world’s most accomplished sculptor of the time. The Laocoön remains in the Vatican Museum to this day.

Michelangelo was profoundly influenced by The Laocoön. It was the turning of a sharp corner in the history of art, and in the enduring treasures of our own faith history. The odds against Michelangelo being at that very place in time to witness the unearthing of the world’s most famed marble sculpture were astronomically impossible. Yet there he was, under duress, and as a direct result of the secular scandal of the Renaissance papacy.

After taking some time to study The Laocoön, Michelangelo left Rome for Florence to resume his work on the sculpture of St. Matthew. The Laocoön was a large part of his motivation. Michelangelo was in awe of its design and tortured realism of human bodies in motion, and was eager to apply that same realism to his first love, marble sculpture. He dug furiously at the marble block in Florence believing that he was to free St. Matthew imprisoned within it.

Two years later, Michelangelo was on his back on high scaffolding painting the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel ceiling. It was a discipline imposed on him by Pope Julius for his disobedience. Michelangelo was angry and resentful, and his powerful emotions exploded into his art on the Sistine ceiling. The expressive and powerful recreation of humans in motion that Michelangelo first witnessed in The Laocoön was the principal model for his design and imagery in the Sistine Chapel ceiling — that, and his own deeply felt anger and disillusionment with the Pope and his ambition.

When Christ placed the Church in the hands of human beings, He knew exactly what was in store for history. The very art with which the world now associates our faith came as the result of the most scandalous adventures in human folly the Church has ever seen.

The Church Triumphant, the Church of faith, is parallel to the Church of human history with all its corruption and failings. It’s a lesson to be learned for those reeling from the burden of scandal in our Church in this day. It’s true that the gates of Hell cannot prevail against it.

But not for lack of trying!

A Shower of Roses

Saint Therese of Lisieux, a Doctor of the Church, left this life at the age of 24. She left behind A Story of a Soul, the most read spiritual biography of all time.

Saint Therese of Lisieux, a Doctor of the Church, left this life at the age of 24. She left behind Story of a Soul, the most read spiritual biography of all time.

In the mid-1980’s, I spent a lot of time with Michelle, a seventeen year-old parishioner who suffered from a terminal brain tumor. In the last weeks of her life on Earth, I visited with her every day. It’s difficult to declare God’s love to a dying teenager and her family.

It was a humbling way to learn that I cannot give away what I do not have. I had no answers to explain their suffering, and could not pretend otherwise. For weeks, Michelle and I together drew closer to the precipice between life and death. I could be but a fellow pilgrim on that path, not a guide.

Michelle’s room was decorated by her loving family and scores of high school friends. It was filled with flowers, stuffed bears, and balloons that reflected their love for Michelle, and their broken hearts over what was happening to her. It was difficult to reconcile that room, with its flowers and gifts that screamed life, with the image of a young girl rapidly departing from it.

On the night before Michelle died, I was with her in that room. After Anointing and Viaticum, she held my hand as I grasped for something that would ease her fear, and give her hope. I don’t know what made me think of it, but I told her of the life of St. Therese of Lisieux, The Little Flower.

I told Michelle all that I knew of Therese, which wasn’t much. She entered the Carmelite convent in Lisieux at fifteen, and left this world on September 30, 1891 at just twenty-four years old.

Her Story of a Soul became one of the most widely read spiritual biographies of all time. I struggled against tears as I spoke of Therese’s “little way,” and asked Michelle to practice it now by surrendering herself to God. By this time, Michelle had lost her ability to speak. She fought against the drugs meant to buffer her pain, seeming to drift in and out of consciousness as she tried hard to listen to the story of St. Therese.

I spoke of St. Therese’s cryptic promise, “After my death, I will let fall a shower of roses.” I told Michelle that I believed the young Therese will meet her on this path, take her hand from mine, and walk with her so she would not be alone. I asked her not to be afraid.

Michelle had not opened her eyes for some time. I wondered if she could even hear me. I told her that some people believe they will receive a rose as a sign that St. Therese has heard their prayer for her intercession. Perhaps I was trying to find hope for myself as much as instill it in Michelle. I looked around her room for a rose among the flowers sent by friends, but there was not one rose to be found there.

When I looked back, I was startled. Michelle was staring at me intently. Too weak to raise her arm, she rested it at her side, her index finger pointing upward at the ceiling as she continued to stare at me. There was an urgency to her stare that seemed to take all the strength she had left. I looked up. Among the several helium balloons tied to her bedposts, one had broken free and drifted to the ceiling. It was one of those silver foil balloons.

Emblazoned upon it was a large, brilliant, vibrant rose.

The balloon had arrived that afternoon, her mother later told me. As soon as Michelle could see that I noticed the rose, she closed her eyes. She never opened them again. The next morning, I was with Michelle as she surrendered her life.

In the days after celebrating the Mass of Christian Burial for Michelle and her family, I was haunted by the memory of the rose balloon. The sheer miracle of it felt so vivid, so alive at the moment it occurred. I had an overwhelming sense of awe, a sense that St. Therese really took Michelle’s hand from mine and walked with her soul the remaining distance. I never spoke of this to anyone until now.

The rose balloon can be easily dismissed now as coincidence, but it didn’t feel that way at first. I could feel what Michelle was feeling as she pointed to it. “Stop looking around my room. It’s right there! Hope is right there!” At that very moment, I felt Michelle’s fear give way to hope.

The days to follow stretched into weeks and months and years. My own trials became many, and heavy. They distorted that moment with Michelle, and hid it in clouds of doubt. In time, my own tribulations drove Michelle’s rose from conscious awareness. I didn’t forget it so much as it just didn’t seem to matter anymore.

Haughty Minds and Simple Signs

Years later, my life and priesthood imploded under the devastating weight of false witness. I spent the eighteen months before my trial living with the Servants of the Paraclete, a community of priests and brothers in New Mexico. One of my housemates was Brother Bernard. He still writes to me. Well into his 70’s now, his Irish wit has not diminished at all, and age has only intensified his simple, trusting — and sometimes irritating — Irish piety. We who serve the Church with advanced degrees in theology and the sciences at times find the combination of sharp wit and simple piety to be, well, humbling. That’s the irritating part.

Brother Bernard has a sort of comic book-like league of spiritual super heroes who, in the simplicity of his faith, will always come to our aid. Clearly, the Wonder Woman of his team of saintly rescuers is Saint Therese of Lisieux, the “Little Flower” and a Doctor of the Church.

When Brother Bernard writes to me, he doesn’t miss a chance to proclaim that he prays to St. Therese for me. When I lived with him, he loved to take out his collection of St. Therese holy cards and other memorabilia. Now every one of his letters contains one of those cards.

We of haughty mind and proud heart have trouble wrapping our brains around the spiritual arena inhabited by Saint Therese. Her “little way” of transforming every moment into a prayer of union with God is hard to relate to when faced with painful and weighty issues — like an unjust imprisonment.

In one of his letters a few years ago, Brother Bernard reminded me of that cryptic promise: “After my death, I will let fall a shower of roses.” He told me that I should look for a rose as a sign that St. Therese hears his prayer.

I thought of the now distant memory of Michelle and the rose balloon. Whatever it had evoked in my own soul then was gone. I scoffed and mocked Brother Bernard’s letter. I am in prison in the harshness of steel and concrete. Roses do not exist here. In all these years in prison, I have never seen a rose. I put Brother Bernard’s letter aside, and put this pious nonsense out of my mind.

Two days later, well before dawn on the morning on October 1st, I emerged from my cell, cup of instant coffee in hand. The cell block was quiet and empty except for one young man sitting alone at a table. As I approached, he complained to me that he had been up all night with an attack of ADHD. A promising artist, the troubled young man had spent the night drawing a card with his treasured colored pencils.

“I’ll trade you this for a cup of coffee,” he said as he handed me the card. I sat down. I had to! On the morning of the feast of St. Therese, I was holding in my hand a stunning three-dimensional sketch of a magnificent, brilliant rose.

+ + +

Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part Two

. . . The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us. Within days of reading Man's Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe's sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue. . . .

See Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part One

As a young priest in 1982, I was only vaguely familiar with the name Maximilian Kolbe. I remember reading of his canonization by Pope John Paul II, but Father Kolbe’s world was far removed from my modern suburban priestly ministry. I was far too busy to step into it.

I didn’t know that nearly two decades later, Father Kolbe’s life, death, and sainthood would be proclaimed on the wall of my prison cell. I also didn’t know this would help define the person I choose to be in prison.

Being a Jew and not a Catholic, Dr. Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning, said nothing about Maximilian’s sainthood or any miracles attributed to his intercession. Instead, Dr. Frankl was moved by the profound charity of Maximilian, which defied the narcissism of our times.

For those unfamiliar with him, the story is simple.

The prisoners of Auschwitz were packed into bunkers like cattle. To encourage informants, the camp had a policy that if any prisoner escaped, 10 others would be randomly chosen for summary execution.

At the morning role call one day, a prisoner from Maximilian’s bunker was missing. Guards chose 10 men to be executed. The 10th fell to the ground and cried for the wife and children he would never see again. Father Kolbe spontaneously stepped forward and said,

“I am a Catholic priest, and I would like to take the place of this man.”

Two weeks later, he alone was still alive among the 10 prisoners chained and condemned to starvation. Maximilian was injected with carbolic acid on August 14, 1941, and his remains unceremoniously incinerated.

For the unbeliever, all that Maximilian was went up in smoke. Viktor Frankl shared some other corner of that horrific prison. The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us.

Within days of reading Man’s Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe’s sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue.

Conventual Franciscan Father James McCurry had been in an airport in Ireland when he heard an Irish priest nearby mention that he corresponds with a priest in a Concord, New Hampshire prison. Father McCurry said he was on his way to visit his order’s house in Granby, Massachusetts and would arrange to visit the Concord prison.

Weeks later, Father McCurry and I met in the prison visiting room. When I asked him what his “assignment” is, he said,

“Well I just finished a biography of St. Maximilian Kolbe. Have you heard of him?”

Father McCurry went on to say that he was involved in Father Maximilian’s cause for sainthood. He had met the man whose great grandfather life was saved by Father Kolbe.

A few years later, Father McCurry arranged a Father Maximilian Kolbe exhibit at the National Holocaust Museum. It was then that he sent me the card depicting Father Maximilian clothed in his Franciscan habit with one sleeve in his prison uniform. I keep the card above my mirror in my cell.

I can never embrace these stone walls. I can’t claim ownership of them. Passively acceding to injustice anywhere contributes to injustice everywhere. Father Maximilian never approved of Auschwitz.

One can’t understand how I now respond to these stone walls, however, without hearing of Father Maximilian’s presence there.

Above my mirror, he refocused my hope in the light of Christ. The darkness can never overcome it.

What hope and freedom there is in that fact! The darkness can never, ever, ever overcome it!

Please share with me your comments below in the comments area.

Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part One

. . . At the very end of his book, Dr. Frankl revealed the name of his inspiration for surviving Auschwitz. He wrote of Sigmund Freud's cynical view that man is self-serving. And a man's instinctual need to survive will trump "quaint notions" such as grace and sacrifice every time. For Dr. Frankl, Auschwitz provided the proof that Freud was wrong. That proof is Father Maximilian Kolbe. . . .

How I came to be in this prison is a story told elsewhere, by me and by others. How I "met" Father Maximilian Kolbe 60 years after he surrendered his life at Auschwitz is a story about actual grace. In his Catholic Catechism, Jesuit Father John Hardon defines actual grace as God's gift of "the special assistance we need to guide the mind and inspire the will" on our path to God. Sometimes, it's very special.

My first three years in prison are a blur in my memory. There is no point trying to find words to express the sense of loss, of alienation, of being cast into an abyss that was not of my own making — a loss that could not be grounded in any reality of mine.

About 1,000 days and nights passed in the abyss before what Father Hardon described as "special assistance" crossed my path.

Someone, somewhere — I don't know who — sent the prison's Catholic chaplain (a layman then) a book entitled Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, M.D. Somewhere in my studies, I heard of this book, but only a prisoner can read it in the same light in which it is written. The chaplain called me to his office. He wanted to know whether he should recommend this book, but didn't have time to read it. He wanted my opinion.

It had been three years since anyone had asked my opinion on anything. I didn't read Dr. Frankl's book so much as devour it. I read it through three times in seven days. As a priest, I often preached that grace is a process and not an event. It is not always so. I was meant to read Man's Search for Meaning at the precise moment that it landed upon my path. A week earlier, I would not have been ready. A week later may have been too late.

I was drowning in the solitary sea of deeply felt loss. I was not going to make it across. My priesthood and my soul were dying. The book, as I have come to call it, is Viktor Frankl's vivid account of how he was alone among his family to survive imprisonment at Auschwitz. This was an imprisonment imposed on him for who he was: a Jew.

There is a central message in this small book. A profound message, so clear in meaning, that it has within it the hallmark of inspired truth. Like Saul thrown from his mount, I remember sinking to the floor when I read it.

“There is a freedom that no one can ever take from you: The freedom to choose the person you are going to be in any set of circumstances.”

This changed everything. Everything! You will see how later. At the very end of his book, Dr. Frankl revealed the name of his inspiration for surviving Auschwitz. He wrote of Sigmund Freud's cynical view that man is self-serving. And a man's instinctual need to survive will trump "quaint notions" such as grace and sacrifice every time. For Dr. Frankl, Auschwitz provided the proof that Freud was wrong.

That proof is Father Maximilian Kolbe.

To be continued in Maximilian and This Man's Search for Meaning Part Two.

Please share your thoughts below in the comment area.

St. Maximilian Kolbe and the Man in the Mirror

. . . I begin each day at the break of dawn in prison by shaving in front of that mirror. This morning ritual has repeated 5,412 times. I seldom cut myself shaving -- a minor miracle as I can see very little of me in that mirror. I often think of St. Paul's cryptic image in his first letter to the Church in Corinth (13:12): "For now I see dimly, as in a mirror, but then I shall see face to face." It is a hopeful image. . . .

For someone on the outside looking in, it must seem an odd place to begin. Virtually every prison cell has one: a small stainless steel sink with a matching toilet welded to its side. Bolted to the cinderblock wall just above it is a small stainless steel mirror, dinged, dented, and scraped so badly that the image it reflects is unrecognizable.

I begin each day at the break of dawn in prison by shaving in front of that mirror. This morning ritual has repeated 5,412 times. [At this writing, it 10,530 times.] I seldom cut myself shaving — a minor miracle as I can see very little of me in that mirror. I often think of St. Paul’s cryptic image in his first letter to the Church in Corinth (13:12): “For now I see dimly, as in a mirror, but then I shall see face to face.” It is a hopeful image.

I sometimes find that my mind calculates dates and their meanings on a sort of autopilot. There came a day when I stood at the mirror to shave and realized that on this day it was Dec. 23, 2006. I have been a priest in prison for the exact amount of time that I was a priest “on the streets” as prisoners like to describe their lives before prison.

From that day until now, I wonder which I see more of in that flawed mirror. Do I see the man who is a priest of 27 years? Or do I see only Prisoner 67546, the identity given to me inside these stone walls?

A strange thing happened on the day after I first reflected — as best I could in that mirror — on who I see. It was Christmas Eve, December 24, 2006, the day that the equation changed. It was the day that I was a priest in prison longer than anywhere else. That night at prison mail call, I had a few Christmas cards. One of them was from Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan priest who once visited me in prison.