“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Feast of Corpus Christi and the Order of Melchizedek

The Priest-King Melchizedek appears in only two verses in the Old Testament but in Salvation History he is a link in a chain from Noah to Abraham to Christ the King.

The Priest-King Melchizedek appears in only two verses in the Old Testament but in Salvation History he is a link in a chain from Noah to Abraham to Christ the King.

“The Lord has sworn and he will not repent; you are a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek.”

— Psalm 110:4

The readers of Beyond These Stone Walls have read and heard a lot about priesthood in the trenches in recent weeks. However, readers have told me that nothing could have prepared them for the shock and awe of our first-ever video post about what happened in my priesthood, “A Documentary Interview with Father Gordon MacRae.”

Many readers have said that they did not know whether to cheer or cry by its end. I hope you do neither. The truth is its own reward and solace, and I am grateful for an opportunity to stand by it. As I told Louisville, Kentucky attorney Frank Friday who was instrumental in finding and publishing this long-lost video, “For a priest in my situation, being heard now feels almost as important as being free! Almost!”

For many readers who have read and listened, one truth is clear. The assault on the priesthood both from within and from without in recent decades is a story of spiritual warfare. Anyone who enters this battle unaware of its real source and meaning is doomed. We who have faced spiritual warfare no longer doubt this.

On the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, Catholics are introduced in the First Reading at Mass to Melchizedek, a priest of God Most High and the King of Salem which, in time, will become “Jerusalem.” He is the first person in the Bible to be referred to as a priest.

This story reaches back in time to the earliest point in Salvation History bearing historical and spiritual resonance with Christ. But first, I must take a short side road into another mystery with a tiny thread of connection in this Great Tapestry of God.

I have long pondered the hidden meaning of one of the most difficult passages to interpret in all of Sacred Scripture. From the Church Fathers of the first few centuries to the present day, scholars have struggled with its meaning. The passage is in the First Letter of Peter.

“For Christ died for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit, in which he went and preached to the spirits in prison, who formerly did not obey, when God’s patience waited in the days of Noah.”

— 1 Peter 3:18-20

These words, put forth by the first Vicar of Christ in the mid-First Century Anno Domini, are cryptic and mysterious. For obvious reasons, I was drawn to the notion that the Risen Christ “went and preached to the spirits in prison, who formerly did not obey.” The connection with “the days of Noah” broadens the possible meanings of this Biblical mystery. For an in-depth look at the theological meaning of this, see my post “To the Spirits in Prison: When Jesus Descended into Hell.”

In the Time of Noah

It is difficult to ponder back 2,000 years into the mindset of Peter and the post-Resurrection early Church. And when we consider Melchizedek’s role in all this, we have to ponder backwards yet another 2,000 years to the time of Abraham. But this reach back into time becomes even more complex. There is a connection to Noah as well, and it reaches back into time immemorial.

I have written in several posts that spiritually, we live in a very important time. We exist today in the 21st Century after Christ while the summons of Abraham — humanity’s first Covenant with God, the first since the Great Flood of Noah’s time — took place in the 21st Century before Christ. It is no cosmic mystery that believers encounter spiritual battle in our time.

For some, St Peter’s reference to Christ attending to “the spirits in prison” refers to what the Apostles Creed declares as “he descended into hell.” In the early Third Century, St Cyril of Alexandria interpreted the above verses from the First Letter of Peter to mean that on Holy Saturday, Christ descended to the dead to make a final offer of salvation to the deceased sinners of Noah’s day.

St Augustine, in the Fifth Century, proposed a more complex interpretation. Citing the “preexistent divinity” of Christ, a theological concept I described in “Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane,” Christ urged the ancient world, through the person of Noah, to repent before being swept away in the floodwaters of God’s judgment.

Modern scholarship proposes another possibility. Some suggest that “the spirits in prison” were never human at all, but rather rebel angels, “the Watchers” who corrupted the world of men before the Flood. This accords with the frequent use of “spirits” for angels in the New Testament (see Matthew 12:45, Luke 10:20, and Hebrews 1:14).

Whether evil or merely unrepentant, this descent to spirits in the spiritual underworld is consistent with millennia of Jewish tradition and, for Christians, a declaration that Christ has reversed the fall of man.

His post-Resurrection descent “to the spirits in prison” may well be a proclamation of victory to the infernal spirits whose power had been crushed by his redeeming death. For those who have faced spiritual battle, this verse from Saint Peter reveals Christ as a cosmic refuge from evil.

In the Order of Melchizedek

The above is background for a fascinating theological connection Saint Peter draws between Christ’s post-Resurrection visit to the nether world and the story of Noah and the Great Flood. That in turn connects to the Priest-King Melchizedek, his blessing upon Abraham, and the Solemnity of Corpus Christi.

In consulting extensive scholarly research on the Melchizedek story, I discovered that much of it was compiled in the Jerome Biblical Commentary by my late uncle, Father George W. MacRae, S.J., Rector of the École biblique et archéologique française de Jérusalem and later Dean of Harvard Divinity School.

Here’s the short version of the back story to the First Reading from Genesis on the Solemnity of Corpus Christi. In the 21st Century before the Birth of the Messiah, in the Eighth Century before Moses encountered Yahweh in the Burning Bush, Abram encountered God as “El Shaddai,” a name which in Hebrew means “God on the Mountain” or “God Most High.”

At Shechem in the Book of Genesis (17:5) El Shaddai established a covenant with Abram promising him descendants and the land of Canaan. At this time God changed Abram’s name to Abraham. Later, a raiding party sent by the Mesopotamian overlords of Canaan was pursued by Abraham after they ravaged his encampment and took prisoners, including his nephew, Lot. Abraham prevailed in battle, rescued the prisoners, including Lot, and restored the bounty of what would one day become Israel.

On his return route, Abraham was met at Salem (later called Jeru-Salem) by its king, Melchizedek. The First Reading at Mass for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi tells this story. With echoes of the Eucharistic Feast, and in a dramatic variation from the Hebrew tradition of animal sacrifice…

“Melchizedek, King of Salem, brought out bread and wine, and being a priest of God Most High [God on the Mountain], he blessed Abram with these words: ‘Blessed be Abram by God Most High, the creator of heaven and earth; and blessed be God Most High, who delivered your foes into your hand.’”

— Genesis 14:18-20

This story preserved for Judaism the living memory of what would become its spiritual capital, Jeru-Salem. Besides being the King of Salem, Melchizedek is the first person in Sacred Scripture to be called a priest. His dominant position in the brief narrative in Genesis (14:18-20) reveals him as King of Kings, the first of the Canaanite kings. His name in Hebrew is “Malchi-Zedek” meaning “My King Is Righteous.” Hebrew tradition ascribes to him another title: Prince of Peace.

Being a patriarch, Melchizedek possessed both ruling authority as a king and religious authority as a priest. His identity as both is widely seen as a foreshadowing of the Kingship and Priestly ministry of Christ. The link between Melchizedek and the patriarchal priesthood is clear in both Jewish and Christian traditions, and is a centerpiece of the New Testament Letter to the Hebrews.

But before I describe that, it is a fascinating revelation that ancient scholarship from both Jewish and Christian sources identifies Melchizedek as the Patriarch Shem, the first-born son of Noah and a righteous survivor of the Great Flood and the Ark. According to the genealogy of Noah in Genesis, Shem lived hundreds of years, well into the time of Abraham.

The genealogy of Jesus in the Gospel of Saint Luke places his lineage from Shem through the line of David to the adoption of the Christ Child by Joseph. The Hebrew tradition that Melchizedek is actually Shem, son of Noah, is in the oldest translations of Genesis. It appears also in the earliest Patristic writings, in the Letters of St Jerome (Letter 73) and in the Commentary on Hebrews by St Thomas Aquinas.

In the New Testament Letter to the Hebrews, Christ is linked to Melchizedek through His Royal Priesthood. For much of the Old Testament, the offices of king and priest stemmed from two different traditions. Aaron (brother of Moses) and his descendants were priests from the tribe of Levi. David and his descendants from the tribe of Judah comprised the line of kings. In only two Biblical figures are these roles combined: Melchizedek and Jesus.

The ministry of Melchizedek in Salem (the early Jerusalem) foreshadows the ministry of Christ in the heavenly Jerusalem (Hebrews 12:22) . The notion of divine inheritance is also present. God has raised his first born Son, exalting him even over the angels (Hebrews 7:26) as well as over the Mosaic Covenant (Hebrews 9:15). Melchizedek, as Shem, is the first born son who inherits the Covenant with Noah.

Lastly, and most importantly for this post, Jesus chooses the elements of his sacrifice in the Eucharistic Feast as bread and wine. In the Heavenly Sanctuary, Jesus continues to offer the Father the sacrifice of His Body and Blood with the sacramental appearance of bread and wine.

The origin of bread and wine as elements of transubstantiation is found in these verses in Genesis (14:18-20) and cited in the Roman Canon of the Mass, which at one time was the only Canon of the Mass, as “the offering of your high priest, Melchizedek.” The solemnity of Corpus Christi reaches across the millennia to the very foundations of the covenant between humanity and God. It extends across the eons between us and Father Abraham, and at its very center in time stands Christ the King and High Priest.

“Eternal Father, I offer you the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity, of Your dearly Beloved Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, in atonement for our sins and the sins of the whole world.”

— From the Divine Mercy Chaplet of Saint Maria Faustina

Judas Iscariot: Who Prays for the Soul of a Betrayer?

Judas Iscariot: The most reviled name in all of Sacred Scripture is judged only by his act of betrayal, but without him among the Apostles is there any Gospel at all?

Judas Iscariot: The most reviled name in all of Sacred Scripture is judged only by his act of betrayal, but without him among the Apostles is there any Gospel at all?

False witness and betrayal are two of the most heinous themes in all of world literature, and Sacred Scripture is no exception. Literature is filled with it because so are we. Not many of us get to live our lives without ever experiencing the false witness of an enemy or the betrayal of a friend.

Recently, I was confronted by the death of someone whom I once thought of as a friend, someone who once betrayed me with a self-serving story of false witness for nothing more redemptive than thirty pieces of silver. It’s an account that will be taken up soon by some other writer for I am not objective enough to bring justice, let alone mercy, to that story.

But for now, there is one aspect of it that I must write about at this of all times. As I was preparing to offer Mass late on a Sunday night, the thought came that I should offer it for this betrayer, this liar, this thief. Every part of my psyche and spirit rebelled against that thought, but in the end, I did what I had been beckoned to do.

It was difficult. It was very difficult. And it cost me even more of myself than that person had already taken. It cost me the perversely comforting experience of eternal resentment. I have not forgiven this false accuser. That is a grace I have not yet discovered. Nor could I so easily set aside the depth of his betrayal.

In offering the Mass, I just asked God not to see this story only as I do. I asked Him not to forever let this soul slip from His grasp, for perhaps there were influences at work that I do not know. have always suspected so.

The obituary said he died “peacefully” just two weeks before his 49th birthday. It said nothing about the cause of death nor anything about a Mass. There was a generic “celebration of his life.” False witness does not leave much to celebrate. Faith, too, had been betrayed for money.

I am still angry with this person even in death, but I take no consolation that his presence in this world has passed. My anger will have to be comfort enough because at some point I realized that my Mass was likely the only one in the world that had been sacrificed for this soul with any legitimate hope for salvation.

That’s the problem with false witness. Its purveyors tell themselves they have no need for salvation. I do not know whether he is any better off for this Mass having been offered, but I do know that I am.

Ever Ancient, Ever New

The experience also focused my attention on history’s most notorious agent of false witness and betrayal, Judas Iscariot. Who has ever prayed for the soul of a betrayer? Not I — at least, not yet — but I also just weeks ago thought it impossible that I would pray for the soul of my accuser.

I cannot get Judas off my mind this week. And as with most Biblical narratives, once I took a hard look, I found a story on its surface and a far greater one in its depths. In those depths is an account of the meaning of the Cross that I found to be staggering today. It changes the way I today see the Cross and the role of Judas in bringing it about. It strikes me that there is not a single place in the narrative of salvation history that does not reflect chaos.

Understanding the Sacrifice of Calvary requires a journey all the way back to the time of Abraham, some 2000 years before the Birth of the Messiah. God had earlier made a covenant with Abraham, a promise to make of his descendants a great nation.

The story of the birth of his son, Isaac, foreshadows that of John the Baptist who in turn foreshadows Jesus. Abraham and Sarah, like Zechariah and Elizabeth, were too old to bear a child, and yet they did. And not just any child. Isaac was the evidence and hope of God’s covenant with Abraham. “I will multiply your descendants as the stars of heaven.”

Then, in Genesis 22, God called Abraham to do the unthinkable: to sacrifice his only son, the one person who was to fulfill God’s covenant. The scene unfolds on Mount Moriah, a place later described in the Book of Chronicles (2 Ch 3:1) as the very site of the future Jerusalem Temple. In obedience, Abraham placed the wood for the sacrifice upon the back of his son, Isaac, who must carry the wood to the hilltop (Gen 22:6).

On that Via Dolorosa, the child Isaac asked his father, “Where is the lamb for the sacrifice?” Abraham’s answer “God will provide Himself the lamb for a burnt offering.” Notice the subtle play on words. There is no punctuation in the original Hebrew of the text. The thought process does not convey, “God Himself will provide the lamb…. but rather, “God will provide Himself, the lamb for sacrifice.”

An Angel of the Lord ultimately stayed Abraham’s hand, and then pointed out a ram in the thicket to complete the sacrifice. In his fascinating book, The Lamb’s Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth (Image Books 1999) author Scott Hahn provides a reflection on the Genesis account that I had long linked to the Cross:

“Christians would later look upon the story of Abraham and Isaac as a profound allegory for the sacrifice of Jesus on the Cross.” (p. 18)

The similarities in the two accounts, says Scott Hahn, are astonishing. The first line of the New Testament – Matthew 1:1 — identifies “Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham…” Jesus, like Isaac, was a faithful father’s only son. Isaac, like Jesus, carried “the wood” for his own sacrifice upon Mount Moriah. In fact, Calvary, the place of the Crucifixion of Christ, is a hillock in the Moriah range.

This places three pivotal Scriptural accounts — each separated by about 1,000 years — in the same place: The site where Abraham was called to sacrifice Isaac, the site of the Jerusalem Temple of Sacrifice, and the site of the Crucifixion of Christ.

In Hebrew, that place is called “Golgotha,” meaning “the place of the skull.” Its origin is uncertain, but there is an ancient Hebrew folklore that the skull of Adam was discovered there. Before the Romans arrived in Palestine, it was a place used for public executions, primarily for stoning. The word “Calvary” is from the Latin “calvaria” meaning “skull.” It was translated into Latin from the Greek, “kranion,” which in turn was a translation of the Hebrew, “Golgotha.”

No angel would stay the Hand of God. God provided Himself the Lamb for the sacrifice. This interplay between these Biblical accounts separated by 2,000 years is the source for our plea in the Mass, “Lamb of God Who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.”

At the Hour of Darkness

The four Gospel accounts in the Canon of Scripture all came into written form after the apostolic witnesses experienced the Resurrection of Jesus. So everything they set out to preserve for the future was seen in that light. The outcome of the story is triumphantly clear in the minds of the New Testament authors. Had the Gospel ended at the Cross, the accounts would be very different.

Judas Iscariot, therefore, is identified early in each Gospel account when he is first summoned by Jesus to the ranks of the Apostles as “the one who would betray him.” John (6:71) adds the Greek term, “diabolos” (6:70), to identify Judas. It is translated “of the devil,” but its connotation is also that of a thief, an informer, a liar, and a betrayer, one drawn into evil by the lure of money.

These adjectives are not presented only to explain the character of Judas, but also to explain that greed left Judas open to Satan. Each Gospel account is clear that Jesus chose him among the Twelve, and in all three Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke, Jesus presents a constant awareness of the coming betrayal of Judas — seemingly as a necessary part of the story.

During Holy Week this year, we hear the full account of the Passion Narrative from Mark (on Palm Sunday) and John (on Good Friday). But for this post I want to focus on the version from Luke. The Gospel of Luke is unique in Scripture. It is the only Scriptural account written by a non-Jewish author.

Luke’s Gospel is the only account with a sequel, Acts of the Apostles, which was also written by Luke. And it is the only Gospel account to include the parables of the Prodigal Son and the Good Samaritan, all of which figure into this story set in motion by the betrayal of Judas.

Luke, though a Gentile and a physician, was also a scholar. He makes few direct references to Old Testament texts, but his Gospel is filled with echoes and allusions to Old Testament themes. Greek Christians may not have readily understood this, but he also wrote his Gospel for Jewish Christians in the Diaspora who would have found in Luke a rich and valuable affirmation of salvation history in their life of faith.

What is most clear to me in Luke’s treatment of Judas is that the story is written with a theme that I readily identify with spiritual warfare. The Passion Narrative has a thread that begins with a story I have written before. In “A Devil in the Desert for the Last Temptation of Christ,” I wrote about the meaning of Satan’s temptation of Christ in the desert. It ends in Luke’s Gospel:

“When the devil had ended every temptation [of Christ], he departed from him until an opportune time.”

— Luke 4:13

Luke constructs his account of the Judas story with threads throughout his Gospel. He shows that the power of Satan, which is frustrated by Jesus in the account of his 40-day temptation in the desert “until an opportune time,” finds its opportunity, not in Jesus, but in Judas whose act of betrayal triggers “the hour of darkness” and the Passion of the Christ:

“Then Satan entered Judas, called Iscariot, who was a member of the Twelve. He went away and conferred with the chief priests….”

— Luke 22:3

The origin and meaning of “Iscariot” is uncertain. It is not known whether it is a name or a title associated with Judas. In Hebrew, it means “man of Keriot”, a small town marking the border of the territory of the Tribe of Judah (see Joshua 15:21.25), to which both Judas and Jesus belonged. Betrayal is all the more bitter when the betrayer is closely associated. The Greek Iskariotes has the cognate sicarias, meaning “assassin,” a name ascribed to a band of outlaws in New Testament times.

It is clear in Luke’s presentation that this act of Judas is equated with original sin, the sin of Adam and Eve lured by the serpent. At the Last Supper, after the Institution of the Eucharist, Jesus said:

“But behold the hand of him who is to betray me is with me at this table, for the Son of Man goes as it has been determined.”

— Luke 22:21

Jesus added, “But woe to that man by whom he is betrayed.” That “woe” is symbolized later in the way the life of Judas ends as described below. The phrase, “as it has been determined,” however, implies that the betrayal was seen not only in its own light but also as a necessary part of God’s plan.

Later, with Judas absent, Jesus warned his disciples at the Mount of Olives, “Pray that you may not enter into temptation.” They did anyway. After the arrest of Jesus at Gethsemane, they scattered. Peter, leader of the Twelve, denied three times that he even knew him. Then the cock crowed (Luke 22:61) just as Jesus predicted. This is often depicted as a literal rooster crowing, but the bugle ending the third-night watch for Roman legions at 3:00 AM was also called the “cockcrow.”

At Gethsemane, Judas betrays Jesus with a kiss, perverting a sign of friendship and affection into one of betrayal and false witness. This is what begins the Passion Narrative and the completion of Salvation History. Jesus tells Judas and the servants of the chief priest:

“When I was with you day after day in the Temple you did not lay a hand on me, but this is your hour, and the power of darkness.”

— Luke 22:53

Later, in the Acts of the Apostles (26:18) Luke identifies the power of darkness as being in opposition to the power of light, an allusion to spiritual warfare. For Luke’s Gospel, it is our ignorance of spiritual warfare that leaves us most vulnerable.

Following immediately after the betrayal of Judas, one of the disciples present draws his sword and cuts off the ear of the servant of the High Priest. In the Gospel of John, the disciple is identified as Peter. This account is very significant and symbolic of the spiritual bankruptcy that Judas set in motion.

In the well-known Parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke’s Gospel, a priest came upon the broken body of an injured man left beaten by robbers on the side of the road. Jesus says in the Parable that the priest just passed by in silence, but this was readily understandable to the Pharisee to whom the parable is told.

The Pharisee, an expert in the Old Covenant law of Moses, understood that the Book of Leviticus forbade a priest who is defiled by the dead body of an alien from offering sacrifice in the Jerusalem Temple. The severed ear of the High Priest’s servant at Gethsemane refers back to the same precept:

“So no one who has a blemish shall draw near [to the Sanctuary], no one who is blind or lame or has a mutilated face…”

— Leviticus 22:18

The symbolism here is that the spiritual bankruptcy of the High Priest, who is not present at the arrest, is represented by his servant. In Luke’s Gospel, and in Luke alone, Jesus heals the ear. It is the sole miracle story in the Passion Narrative of any of the four Gospels and represents that Jesus wields the power of God even over the High Priest and Temple sacrifice.

When the role of Judas Iscariot is complete, he faces a bizarre end in Luke. The Gospel of Matthew (26:56) has Judas despairing and returning his 30 pieces of silver to the Temple. Luke, in Acts of the Apostles (1:16-20) explains that the actions of Judas were “so that the Scriptures may be fulfilled.” But in Luke, Judas meets an even more bitter end, bursting open and falling headlong as “all his bowels gushed out.” The field where this happened then became known as the Field of Blood, and the money that purchased it, “blood money.”

The point of the story of Judas in the Gospel of Luke is that discipleship engages us in spiritual warfare, and spiritual blindness leaves us vulnerable to our own devices, as it did Judas. This life “is your hour, and the power of darkness.” The plot against Jesus was Satan’s, and Judas was but its pawn.

So who prays for the souls of our betrayers? I did, and it was difficult. It was very difficult. But I can see today why Jesus called us to pray for those who persecute us. It is not only for their sake but for ours.

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Please share this post. For further reading, the Easter Season comes alive in these other posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

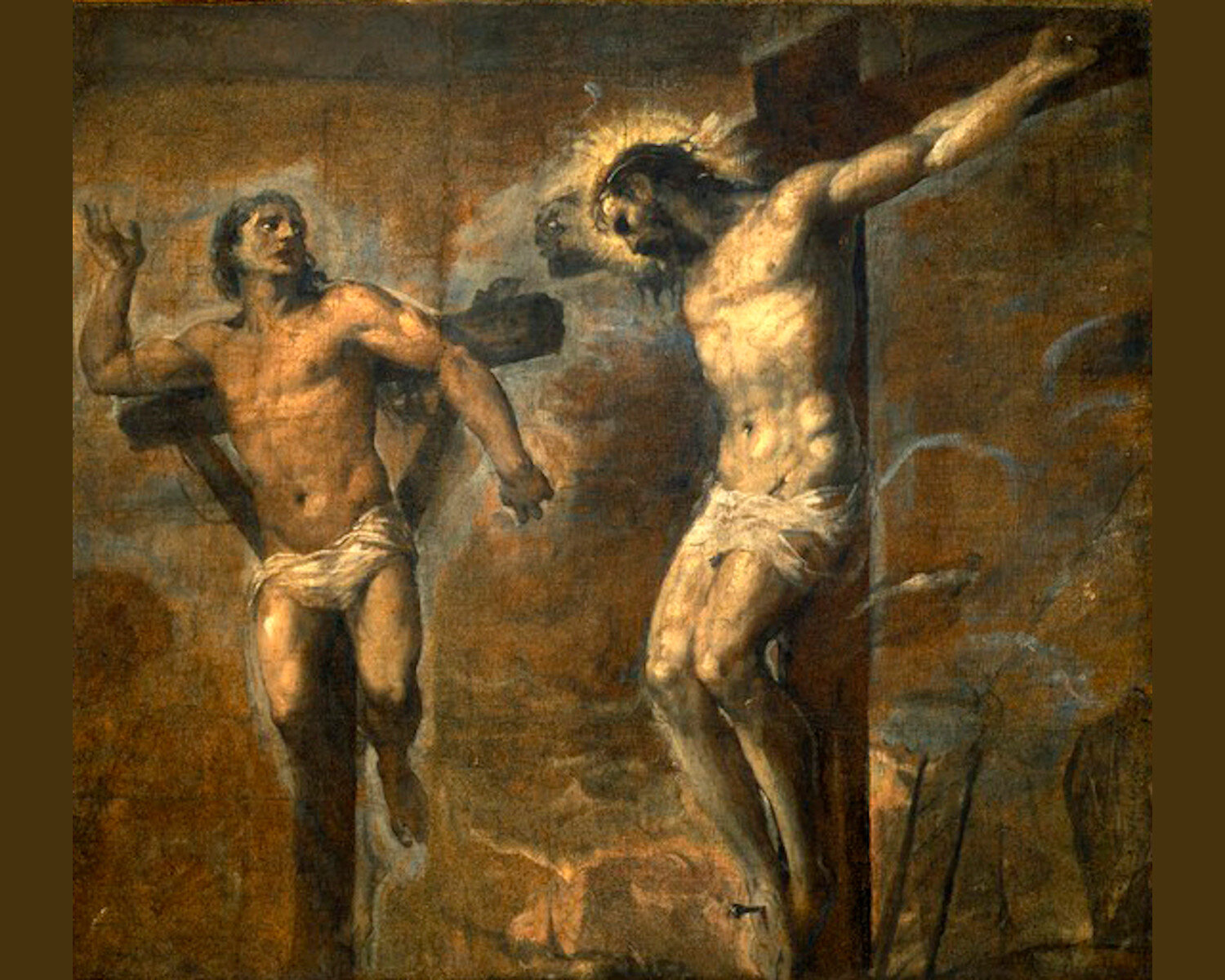

Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Christians.

Who was Saint Dismas, the penitent criminal, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Salvation.

“All who see me scoff at me. They mock me with parted lips; they wag their heads.”

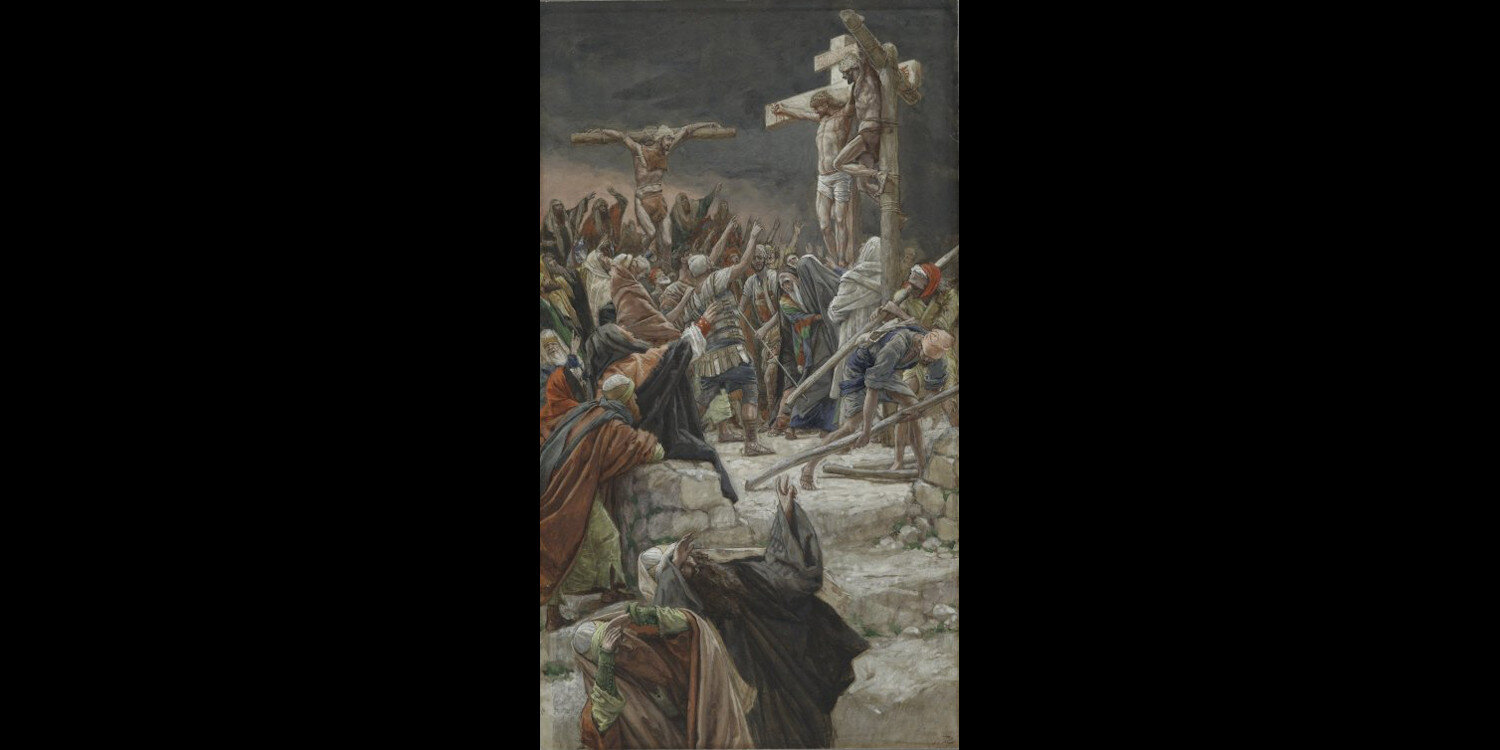

During Holy Week one year, I wrote “Simon of Cyrene, the Scandal of the Cross, and Some Life Sight News.” It was about the man recruited by Roman soldiers to help carry the Cross of Christ. I have always been fascinated by Simon of Cyrene, but truth be told, I have no doubt that I would react with his same spontaneous revulsion if fate had me walking in his sandals that day past Mount Calvary.

Some BTSW readers might wish for a different version, but I cannot write that I would have heroically thrust the Cross of Christ upon my own back. Please rid yourselves of any such delusion. Like most of you, I have had to be dragged kicking and screaming into just about every grace I have ever endured. The only hero at Calvary was Christ. The only person worth following up that hill — up ANY hill — is Christ. I follow Him with the same burdens and trepidation and thorns in my side as you do. So don’t follow me. Follow Him.

This Holy Week, one of many behind these stone walls, has caused me to use a wider angle lens as I examine the events of that day on Mount Calvary as the Evangelists described them. This year, it is Dismas who stands out. Dismas is the name tradition gives to the man crucified to the right of the Lord, and upon whom is bestowed a dubious title: the “Good Thief.”

As I pondered the plight of Dismas at Calvary, my mind rolled some old footage, an instant replay of the day I was sent to prison — the day I felt the least priestly of all the days of my priesthood.

It was the mocking that was the worst. Upon my arrival at prison after trial late in 1994, I was fingerprinted, photographed, stripped naked, showered, and unceremoniously deloused. I didn’t bother worrying about what the food might be like, or whether I could ever sleep in such a place. I was worried only about being mocked, but there was no escaping it. As I was led from place to place in chains and restraints, my few belongings and bedding stuffed into a plastic trash bag dragged along behind me, I was greeted by a foot-stomping chant of prisoners prepped for my arrival: “Kill the priest! Kill the priest! Kill the priest!” It went on into the night. It was maddening.

It’s odd that I also remember being conscious, on that first day, of the plight of the two prisoners who had the misfortune of being sentenced on the same day I was. They are long gone now, sentenced back then to just a few years in prison. But I remember the walk from the courthouse in Keene, New Hampshire to a prison-bound van, being led in chains and restraints on the “perp-walk” past rolling news cameras. A microphone was shoved in my face: “Did you do it, Father? Are you guilty?”

You may have even witnessed some of that scene as the news footage was recently hauled out of mothballs for a WMUR-TV news clip about my new appeal. Quickly led toward the van back then, I tripped on the first step and started to fall, but the strong hands of two guards on my chains dragged me to my feet again. I climbed into the van, into an empty middle seat, and felt a pang of sorrow for the other two convicted criminals — one in the seat in front of me, and the other behind.

“Just my %¢$#@*& luck!” the one in front scowled as the cameras snapped a few shots through the van windows. I heard a groan from the one behind as he realized he might vicariously make the evening news. “No talking!” barked a guard as the van rolled off for the 90 minute ride to prison. I never saw those two men again, but as we were led through the prison door, the one behind me muttered something barely audible: “Be strong, Father.”

Revolutionary Outlaws

It was the last gesture of consolation I would hear for a long, long time. It was the last time I heard my priesthood referred to with anything but contempt for years to come. Still, to this very day, it is not Christ with whom I identify at Calvary, but Simon of Cyrene. As I wrote in “Simon of Cyrene and the Scandal of the Cross“:

“That man, Simon, is me . . . I have tried to be an Alter Christus, as priesthood requires, but on our shared road to Calvary, I relate far more to Simon of Cyrene. I pick up my own crosses reluctantly, with resentment at first, and I have to walk behind Christ for a long, long time before anything in me compels me to carry willingly what fate has saddled me with . . . I long ago had to settle for emulating Simon of Cyrene, compelled to bear the Cross in Christ’s shadow.”

So though we never hear from Simon of Cyrene again once his deed is done, I’m going to imagine that he remained there. He must have, really. How could he have willingly left? I’m going to imagine that he remained there and heard the exchange between Christ and the criminals crucified to His left and His right, and took comfort in what he heard. I heard Dismas in the young man who whispered “Be strong, Father.” But I heard him with the ears of Simon of Cyrene.

Like a Thief in the Night

Like the Magi I wrote of in “Upon a Midnight Not So Clear,” the name tradition gives to the Penitent Thief appears nowhere in Sacred Scripture. Dismas is named in a Fourth Century apocryphal manuscript called the “Acts of Pilate.” The text is similar to, and likely borrowed from, Saint Luke’s Gospel:

“And one of the robbers who were hanged, by name Gestas, said to him: ‘If you are the Christ, free yourself and us.’ And Dismas rebuked him, saying: ‘Do you not even fear God, who is in this condemnation? For we justly and deservedly received these things we endure, but he has done no evil.’”

What the Evangelists tell us of those crucified with Christ is limited. In Saint Matthew’s Gospel (27:38) the two men are simply “thieves.” In Saint Mark’s Gospel (15:27), they are also thieves, and all four Gospels describe their being crucified “one on the left and one on the right” of Jesus. Saint Mark also links them to Barabbas, guilty of murder and insurrection. The Gospel of Saint John does the same, but also identifies Barabbas as a robber. The Greek word used to identify the two thieves crucified with Jesus is a broader term than just “thief.” Its meaning would be more akin to “plunderer,” part of a roving band caught and given a death penalty under Roman law.

Only Saint Luke’s Gospel infers that the two thieves might have been a part of the Way of the Cross in which Saint Luke includes others: Simon of Cyrene carrying Jesus’ cross, and some women with whom Jesus spoke along the way. We are left to wonder what the two criminals witnessed, what interaction Simon of Cyrene might have had with them, and what they deduced from Simon being drafted to help carry the Cross of a scourged and vilified Christ.

In all of the Gospel presentations of events at Golgotha, Jesus was mocked. It is likely that he was at first mocked by both men to be crucified with him as the Gospel of St. Mark describes. But Saint Luke carefully portrays the change of heart within Dismas in his own final hour. The sense is that Dismas had no quibble with the Roman justice that had befallen him. It seems no more than what he always expected if caught:

“One of the criminals who were hanged railed at him, saying, ‘Are you not the Christ? Save yourself and us!’ But the other rebuked him, saying, ‘Do you not fear God since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed justly, for we are receiving the due reward of our deeds; but this man has done nothing wrong.’ ”

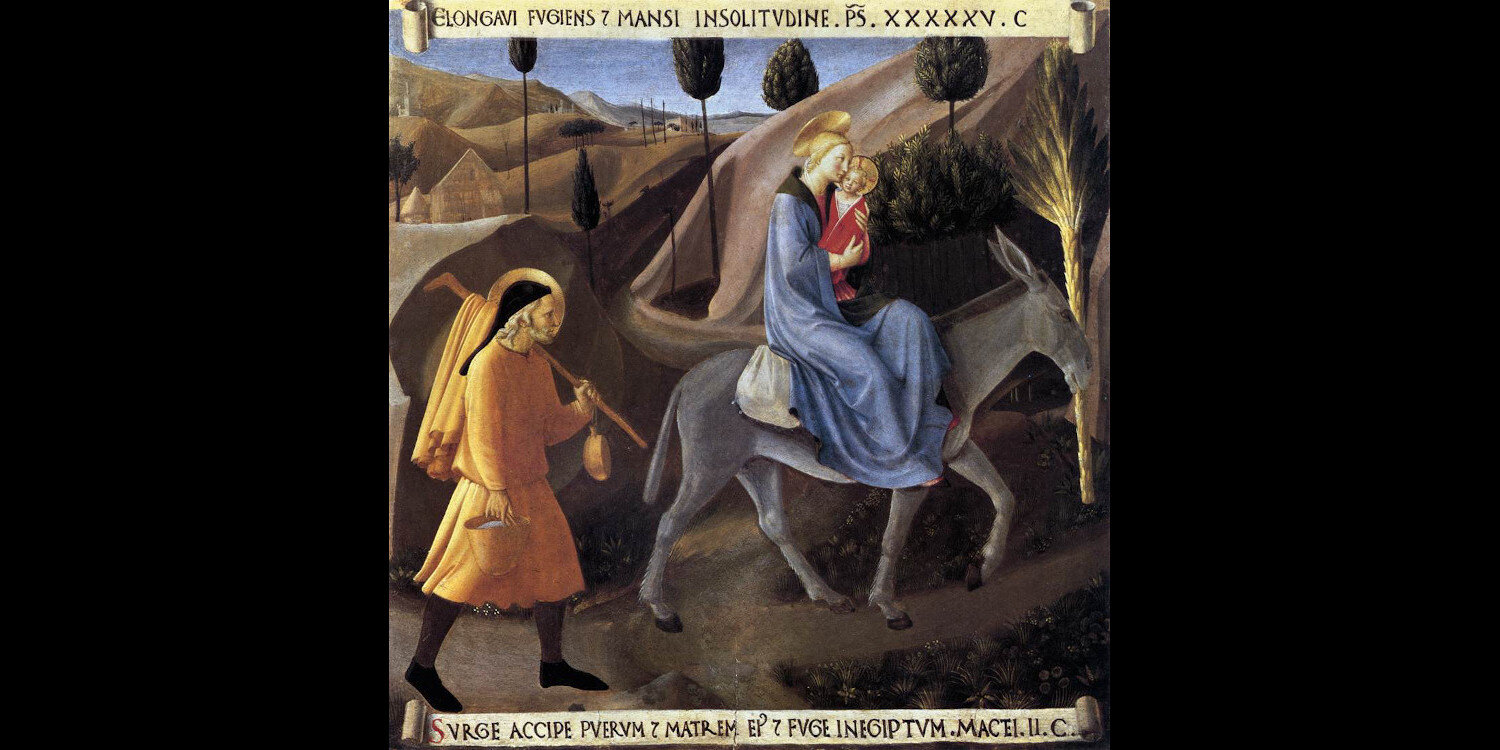

The Flight into Egypt

The name, “Dismas” comes from the Greek for either “sunset” or “death.” In an unsubstantiated legend that circulated in the Middle Ages, in a document known as the “Arabic Gospel of the Infancy,” this encounter from atop Calvary was not the first Gestas and Dismas had with Jesus. In the legend, they were a part of a band of robbers who held up the Holy Family during the Flight into Egypt after the Magi departed in Saint Matthews Gospel (Matthew 2:13-15).

This legendary encounter in the Egyptian desert is also mentioned by Saint Augustine and Saint John Chrysostom who, having heard the same legend, described Dismas as a desert nomad, guilty of many crimes including the crime of fratricide, the murder of his own brother. This particular part of the legend, as you will see below, may have great symbolic meaning for salvation history.

In the legend, Saint Joseph, warned away from Herod by an angel (Matthew 2:13-15), opted for the danger posed by brigands over the danger posed by Herod’s pursuit. Fleeing with Mary and the child into the desert toward Egypt, they were confronted by a band of robbers led by Gestas and a young Dismas. The Holy Family looked like an unlikely target having fled in a hurry, and with very few possessions. When the robbers searched them, however, they were astonished to find expensive gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh — the Gifts of the Magi. However, in the legend Dismas was deeply affected by the infant, and stopped the robbery by offering a bribe to Gestas. Upon departing, the young Dismas was reported to have said:

“0 most blessed of children, if ever a time should come when I should crave thy mercy, remember me and forget not what has passed this day.”

Paradise Found

The most fascinating part of the exchange between Jesus and Dismas from their respective crosses in Saint Luke’s Gospel is an echo of that legendary exchange in the desert 33 years earlier — or perhaps the other way around:

“‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingly power.’ And he said to him, ‘Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.’”

The word, “Paradise” used by Saint Luke is the Persian word, “Paradeisos” rarely used in Greek. It appears only three times in the New Testament. The first is that statement of Jesus to Dismas from the Cross in Luke 23:43. The second is in Saint Paul’s description of the place he was taken to momentarily in his conversion experience in Second Corinthians 12:3 — which I described in “The Conversion of Saint Paul and the Cost of Discipleship.” The third is the heavenly paradise that awaits the souls of the just in the Book of Revelation (2:7).

In the Old Testament, the word “Paradeisos” appears only in descriptions of the Garden of Eden in Genesis 2:8, and in the banishment of Cain after the murder of his brother, Abel:

“Cain left the presence of the Lord and wandered in the Land of Nod, East of Eden.”

Elsewhere, the word appears only in the prophets (Isaiah 51:3 and Ezekiel 36:35) as they foretold a messianic return one day to the blissful conditions of Eden — to the condition restored when God issues a pardon to man.

If the Genesis story of Cain being banished to wander “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden” is the symbolic beginning of our human alienation from God — the banishment from Eden marking an end to the State of Grace and Paradise Lost — then the Dismas profession of faith in Christ’s mercy is symbolic of Eden restored — Paradise Regained.

From the Cross, Jesus promised Dismas both a return to spiritual Eden and a restoration of the condition of spiritual adoption that existed before the Fall of Man. It’s easy to see why legends spread by the Church Fathers involved Dismas guilty of the crime of fratricide just as was Cain.

A portion of the cross upon which Dismas is said to have died alongside Christ is preserved at the Church of Santa Croce in Rome. It’s one of the Church’s most treasured relics. Catholic apologist, Jim Blackburn has proposed an intriguing twist on the exchange on the Cross between Christ and Saint Dismas. In “Dismissing the Dismas Case,” an article in the superb Catholic Answers Magazine Jim Blackburn reminded me that the Greek in which Saint Luke’s Gospel was written contains no punctuation. Punctuation had to be added in translation. Traditionally, we understand Christ’s statement to the man on the cross to his right to be:

“Truly I say to you, today you will be with me in Paradise.”

The sentence has been used by some non-Catholics (and a few Catholics) to discount a Scriptural basis for Purgatory. How could Purgatory be as necessary as I described it to be in “The Holy Longing” when even a notorious criminal is given immediate admission to Paradise? Ever the insightful thinker, Jim Blackburn proposed a simple replacement of the comma giving the verse an entirely different meaning:

“Truly I say to you today, you will be with me in Paradise.”

Whatever the timeline, the essential point could not be clearer. The door to Divine Mercy was opened by the events of that day, and the man crucified to the right of the Lord, by a simple act of faith and repentance and reliance on Divine Mercy, was shown a glimpse of Paradise Regained.

The gift of Paradise Regained left the cross of Dismas on Mount Calvary. It leaves all of our crosses there. Just as Cain set in motion our wandering “In the Land of Nod, East of Eden,” Dismas was given a new view from his cross, a view beyond death, away from the East of Eden, across the Undiscovered Country, toward eternal home.

Saint Dismas, pray for us.

+ + +

Angelic Justice: Saint Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed

Saint Michael the Archangel is often depicted wielding a sword and a set of scales to vanquish Satan. His scales have an ancient and surprising meaning.

Saint Michael the Archangel is often depicted wielding a sword and a set of scales to vanquish Satan. His scales have an ancient and surprising meaning.

I worked for days on a post about Saint Michael the Archangel. I finally finished it this morning, exactly one week before the Feast of the Archangels, then rushed off to work in the prison library. When I returned four hours later to print the post and get it into the mail to Charlene, my friend Joseph stopped by. You might remember Joseph from a few of my posts, notably “Disperse the Gloomy Clouds of Night” in Advent and “Forty Days and Forty Nights” in Lent.

Well, you can predict where this is going. As soon as I returned to my cell, Joseph came in to talk with me. Just as I turned on my typewriter, Joseph reached over and touched it. He wasn’t aware of the problem with static charges from walking across these concrete floors. Joseph’s unintentional spark wiped out four days of work and eight pages of text.

It’s not the first time this has happened. I wrote about it in “Descent into Lent” last year, only then I responded with an explosion of expletives. Not so this time. As much as I wanted to swear, thump my chest, and make Joseph feel just awful, I couldn’t. Not after all my research on the meaning of the scales of Saint Michael the Archangel. They very much impact the way I look at Joseph in this moment. Of course, for the 30 seconds or so after it happened, it’s just as well that he wasn’t standing within reach!

This world of concrete and steel in which we prisoners live is very plain, but far from simple. It’s a world almost entirely devoid of what Saint Michael the Archangel brings to the equation between God and us. It’s also a world devoid of evidence of self-expression. Prisoners eat the same food, wear the same uniforms, and live in cells that all look alike.

Off the Wall, And On

In these cells, the concrete walls and ceilings are white — or were at one time — the concrete floors are gray, and the concrete counter running halfway along one wall is dark green. On a section of wall for each prisoner is a two-by-four foot green rectangle for posting family photos, a calendar and religious items. The wall contains the sole evidence of self-expression in prison, and you can learn a lot about a person from what’s posted there.

My friend, Pornchai, whose section of wall is next to mine, had just a blank wall two years ago. Today, not a square inch of green shows through his artifacts of hope. There are photos of Joe and Karen Corvino, the foster parents whose patience impacted his life, and Charlene Duline and Pierre Matthews, his new Godparents. There’s also an old photo of the home in Thailand from which he was taken at age 11, photos of some of the ships described in “Come, Sail Away!” now at anchor in new homes. There’s also a rhinoceros — no clue why — and Garfield the Cat. In between are beautiful icons of the Blessed Mother, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Saint Pio, and one of Saint Michael the Archangel that somehow migrated from my wall over to Pornchai’s.

My own wall evolved over time. The only family photos I had are long lost, and I haven’t seen my family in many years. It happens to just about every prisoner after ten years or so. In my first twelve years in prison I was moved sixteen times, and each time I had to quickly take my family photos off the wall. Like many prisoners here for a long, long time, there came a day when I took my memories down to move, then just didn’t put them back up again. A year ago, I had nothing on the wall, then a strange transformation of that small space began to take shape.

When These Stone Walls — the blog, not the concrete ones — began last year, some readers started sending me beautiful icons and holy cards. The prison allows them in mail as long as they’re not laminated in plastic. Some made their way onto my wall, and slowly over the last year it filled with color and meaning again.

It’s a mystery why, but the most frequent image sent to me by TSW readers is that of Saint Michael the Archangel. There are five distinct icons of him on the wall, plus the one that seems to prefer Pornchai’s side. These stone walls — the concrete ones, not the blog — are filled with companions now.

There’s another icon of Saint Michael on my coffee cup — the only other place prisoners always leave their mark — and yet another inside and above the cell door. That one was placed there by my friend, Alberto Ramos, who went to prison at age 14 and turned 30 last week. It appeared a few months ago. Alberto’s religious roots are in Caribbean Santeria. He said Saint Michael above the door protects this cell from evil. He said this world and this prison greatly need Saint Michael.

Who Is Like God?

The references to the Archangel Michael are few and cryptic in the canon of Hebrew and Christian Scripture. In the apocalyptic visions of the Book of Daniel, he is Michael, your Prince, “who stands beside the sons of your people.” In Daniel 12:1 he is the guardian and protector angel of Israel and its people, and the “Great Prince” in Heaven who came to the aid of the Archangel Gabriel in his contest with the Angel of Persia (Daniel 10:13, 21).

His name in Hebrew — Mikha’el — means “Who is like God?” It’s posed as a question that answers itself. No one, of course, is like God. A subsidiary meaning is, “Who bears the image of God,” and in this Michael is the archetype in Heaven of what man himself was created to be: the image and likeness of God. Some other depictions of the Archangel Michael show him with a shield bearing the image of Christ. In this sense, Michael is a personification, as we’ll see below, of the principal attribute of God throughout Scripture.

Outside of Daniel’s apocalyptic vision, the Archangel Michael appears only two more times in the canon of Sacred Scripture. In Revelation 12:7-9 he leads the army of God in a great and final battle against the army of Satan. A very curious mention in the Epistle of Saint Jude (Jude 1:9) describes Saint Michael’s dispute with Satan over the body of Moses.

This is a direct reference to an account in the Apocrypha, and demonstrates the importance and familiarity of some of the apocryphal writings in the Israelite and early Christian communities. Saint Jude writes of the account as though it is quite familiar to his readers. In the Assumption of Moses in the apocryphal Book of Enoch, Michael prevails over Satan, wins the body of Moses, and accompanies him into Heaven.

It is because of this account that Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus in the account of the Transfiguration in Matthew 11. Moses and Elijah are the two figures in the Hebrew Scriptures to hear the voice of God on Mount Sinai, and to be assumed bodily into Heaven — escorted by Saint Michael the Archangel according to the Aggadah, the collection of milennia of rabbinic lore and custom.

Saint Michael as the Divine Measure of Souls

In each of the seven images of Saint Michael the Archangel sent to me by TSW readers, he is depicted brandishing a sword in triumph over Satan subdued at his feet. In five of the icons, he also holds a set of scales above the head of Satan. A lot of people confuse the scales with those of “Lady Justice” the famous American icon. Those scales symbolize the equal application of law and justice in America. It’s a high ideal, but one that too often isn’t met in the American justice system. I cited some examples in “The Eighth Commandment.”

The scales of Saint Michael also depict justice, but of another sort. Presumably that’s why so many readers sent me his image, and I much appreciate it. However, some research uncovered a far deeper symbolic meaning for the Archangel’s scales. The primary purpose of the scales is not to measure justice, but to weigh souls. And there’s a specific factor that registers on Saint Michael’s scales. They depict his role as the measure of mercy, the highest attribute of God for which Saint Michael is the personification. The capacity for mercy is what it most means to be in the image and likeness of God. The primary role of Saint Michael the Archangel is to be the advocate of justice and mercy in perfect balance — for justice without mercy is little more than vengeance.

That’s why God limits vengeance as summary justice. In Genesis chapter 4, Lamech, a descendant of Cain, vows that “if Cain is avenged seven-fold then Lamech is avenged seventy-seven fold.” Jesus later corrects this misconception of justice by instructing Peter to forgive “seventy times seven times.”

Our English word, “Mercy” doesn’t actually capture the full meaning of what is intended in the Hebrew Scriptures as the other side of the justice equation. The word in Hebrew is ”hesed,” and it has multiple tiers of meaning. It was translated into New Testament Greek as “eleos,” and then translated into Latin as “misericordia” from which we derive the English word, “mercy.” Saint Michael’s scales measure ”hesed,” which in its most basic sense means to act with altruism for the good of another without anything of obvious value in return. It’s the exercise of mercy for its own sake, a mercy that is the highest value of Judeo-Christian faith.

Sacred Scripture is filled with examples of hesed as the chief attribute of God and what it means to be in His image. That ”the mercy of God endures forever” is the central and repeated message of the Judeo-Christian Scriptures. The references are too many to name, but as I was writing this post, I spontaneously thought of a few lines from Psalm 85:

“Mercy and faithfulness shall meet. Justice and peace shall kiss. Truth shall spring up from the Earth, and justice shall look down from Heaven.”

The domino effect of hesed-mercy is demonstrated in Psalm 85. Faithfulness and truth will arise out of it, and together all three will comprise justice. In researching this, I found a single, ancient rabbinic reference attributing authorship of Psalm 85 to the only non-human instrument of any Psalm or verse of Scripture: Saint Michael the Archangel, himself. According to that legend, Psalm 85 was given by the Archangel along with the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai.

Saint Thomas Aquinas described Saint Michael as “the breath of the Redeemer’s spirit who will, at the end of the world, combat and destroy the Anti-Christ as he did Lucifer in the beginning.” This is why St. Michael is sometimes depicted bearing a shield with the image of Christ. It is the image of Christ in His passion, imprinted upon the veil of St. Veronica. Veronica is a name that appears nowhere in Scripture, but is simply a name assigned by tradition to the unnamed woman with the veil. The name Veronica comes from the Latin “vera icon” meaning “true image.”

Saint Thomas Aquinas and many Doctors of the Church regarded Saint Michael as the angel of Exodus who, as a pillar of cloud and fire, led Israel out of slavery. Christian tradition gives to Saint Michael four offices: To fight against Satan, to measure and rescue the souls of the just at the hour of death, to attend the dying and accompany the just to judgment, and to be the Champion and Protector of the Church.

His feast day, assigned since 1970 to the three Archangels of Scripture, was originally assigned to Saint Michael alone since the sixth century dedication of a church in Rome in his honor. The feast was originally called Michaelmas meaning, “The Mass of St. Michael.” The great prayer to Saint Michael, however, is relatively new. It was penned on October 13, 1884, by Pope Leo XIII after a terrifying vision of Saint Michael’s battle with Satan:

St. Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle. Be our protection against the wickedness and snares of the devil. May God rebuke him, we humbly pray, and do thou, 0 Prince of the heavenly Host, by the power of God, cast into Hell Satan and all the evil spirits who prowl about the world seeking the ruin of souls. Amen.

It’s an important prayer for the Church, especially now. I know the enemies of the Church lurk here, too. There are some who come here not for understanding, or the truth, but for ammunition. For them the very concept of mercy, forgiveness, and inner healing is anathema to their true cause. I once scoffed at the notion that evil surrounds us, but I have seen it. I think every person falsely accused has seen it.

Donald Spinner, mentioned in “Loose Ends and Dangling Participles,” gave Pornchai a prayer that was published by the prison ministry of the Paulist National Catholic Evangelization Association. Pornchai asked me to mention it in this post. It’s a prayer that perfectly captures the meaning of Saint Michael the Archangel’s Scales of Hesed:

“Prayer for Justice and Mercy

Jesus, united with the Father and the Holy Spirit, give us your compassion for those in prison. Mend in mercy the broken in mind and memory. Soften the hard of heart, the captives of anger. Free the innocent; parole the trustworthy. Awaken the repentance that restores hope. May prisoners’ families persevere in their love. Jesus, heal the victims of crime; they live with the scars. Lift to eternal peace those who die. Grant victims and their families the forgiveness that heals. Give wisdom to lawmakers and those who judge. Instill prudence and patience in those who guard. Make those in prison ministry bearers of your light, for ALL of us are in need of your mercy! Amen.”