“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Passion of the Christ in an Age of Outrage

Prayerful observance of Holy Week is a challenge in a climate of pandemic restrictions and political outrage. Spend time with us this week Beyond These Stone Walls.

Prayerful observance of Holy Week is a challenge in a climate of woke ideology and political outrage. Spend time with us this week Beyond These Stone Walls.

Something timely and fascinating was unearthed in the days just before Holy Week in 2021. It actually began in 1960 near the Dead Sea in Qumran, an ancient Hebrew settlement in Jordan. Archeologists discovered fragments showing that caves there were used as a hide-out by Bar Kochba’s rebel army which staged a three-year revolt against the Roman occupation of Jerusalem from AD 132-135.

The 1960 discovery included Roman coins, arrows, and a fragment of parchment bearing sixteen verses in Hebrew from the Book of Exodus. In a deep cave in Wadi Haver, archeologists also discovered several of Bar Kochba’s letters on papyri and wood.

Sixty-one years later, on March 16, 2021 the Israeli government announced the discovery of dozens of Dead Sea Scroll fragments of Hebrew texts from the Prophets Zechariah and Nahum from an adjacent cave. The “Cave of Horrors,” as it is called, contained other evidence that it was used by followers of Bar Kochba to evade the Roman armies. The cave is located in the Judean desert about 262 feet (80 meters) below a cliff top.

The Bar Kochba rebellion took place about 60 years after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, an event predicted by Jesus during his triumphant entry into Jerusalem (Luke 19:28ff). In AD 70, Romans destroyed the Temple. The revolt of Bar Kochba was triggered 60 years later when Roman emperor Hadrian decided to erect a shrine to the mythological Roman god, Jupiter, upon the site of the Temple.

Emperor Hadrian came personally to Judea to put down the Bar Kochba revolt which ultimately cost the lives of over a half million Jews. The revolt was called the “Liberation of Jerusalem” by its adherents. It was led by Simon Ben Kosibah, known to the documents of the early Christian Church as Bar Kochba.

Hadrian and his General, Sextus Julius Severus, crushed the revolt by a long, slow starvation of the Jewish revolutionaries and their families who had been driven into the desert to take refuge in the desert caves. When it was all over, Hadrian destroyed what was left of Jerusalem. He then decreed that the whole Jewish nation should be barred, from that day forward, from entering the City of Jerusalem and its surrounding area so that “they may not even view from afar their ancestral home.”

Little is known today about the state of Christianity at the time of the Bar Kochba revolt. It was a time in which a break between synagogue and church was taking place for Jewish Christians. A succession of thirteen Jewish-Christian bishops ruled Jerusalem until the time of Hadrian. At the time of the first destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in AD 70, Simeon, son of Clopas, was Bishop of Jerusalem and was martyred there. The Second Century historian Eusebius, reported that between the martyrdom of Simeon and the Bar Kochba revolt, “many thousands of Jews had come to believe in Christ.”

A Revolution in the Soul

These remnants of a revolution seem an almost fitting discovery just before Holy Week in this of all years. I believe that the bones of Bar Kochba’s faithful Jewish and Jewish-Christian revolutionaries are calling to us from those caves. I have never written a Holy Week post like this before because we have never had a Holy Week like this before in our lifetimes. For the second year in a row, many Catholics face a drastic reduction in their ability to participate in the liturgy and Sacraments of their Faith.

The first time Holy Week was limited by fears of a pandemic — in Holy Week 2020 — Christianity was caught off guard on a global scale. We never imagined that the restrictions set in place by both civil and religious authorities would further impede our faith as we approach another Holy Week a year later. We never imagined that many of our spiritual leaders would continue their passive acceptance of the severe limits placed on our practice of faith. I wrote of this at the turn of the year in “A Year in the Grip of Earthly Powers.”

On what we today call “Passion Sunday,” Jesus entered Jerusalem as the triumphant Son of David, a title given to him by Sacred Scripture. As he entered the Holy City, he wept. It is notable that he did not weep over his knowledge that he enters Jerusalem to commence the Passion of the Christ. Saint Luke’s Passion Narrative makes clear that Jesus wept over Jerusalem and what he knew to be the coming destruction of the Temple and Holy City by Earthly Powers. He knew that many would lose their lives in revolt against it.

Many people in our era are just now awakening to a revolution in the soul as clarity dawns that demonic forces behind so-called “cancel culture” are using a pandemic to suppress our churches, our liturgy, our voices, and our communal values and expressions of faith. Many are also awakening to the reality that some — but certainly not all — of our religious leaders have acquiesced to this suppression, most by their silence, but some by outright endorsement of government-imposed shutdowns.

I have written of at least two instances in which the courts have overruled political impositions on Mass attendance and Catholic practice only to have the local Catholic bishop re-impose the same restrictions the courts had declared unconstitutional. I feel indebted to the many priests — and, in fairness, some bishops too — who have found courage in their fidelity to reject the modern version of one of my most memorable Holy Week posts: “The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’.”

That Whisper in the Ear of Judas

There is another force, also seemingly demonic in its origin, that has impinged upon our expressions of fidelity in the public square. I could sense it all around us throughout the last year and it has not abated. It has just festered and grown deeper within many of us as persons and as communities. I had a hard time putting a name on it until I saw it spelled out by one of my favorite columnists in The Wall Street Journal.

On March 9, 2021, political columnist Gerald F. Seib published a masterful analysis entitled “The Perpetual Outrage Machine Churns On.” You may not be able to read it without a subscription but I will give a brief summary of its evidence.

Two months after the January 6 events at the U.S. Capitol, prison-like fencing still surrounded the area. In Minneapolis, the trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin over the death of George Floyd — seemingly every horrid moment of it caught on national television — has commenced amid another round of protests. Innocent Asian Americans have suddenly become targets of physical and verbal assault across the nation. Four women at a Bed and Body Works store in Arizona erupted into a wild brawl. Eight persons were killed by a single gunman in a spa in Atlanta. Ten more were murdered while shopping in a Colorado supermarket.

This list of present day atrocities spawned by rage could go on for pages. There is an influence behind it. A master opportunist has been doing what he does best. In Holy Week 2020, I wrote “Satan at the Last Supper: Hours of Darkness & Light.” Its point was that the whisper into the ear of Judas at the Last Supper was preceded by other events. Before it happened, Satan entered into Judas (Luke 22:3) as Judas entered into a deal with the chief priests to betray Christ. His sin of greed left him vulnerable to the exploitation of Satan and his minions. That is always the case. The mere whisper in the dark is never enough. Through a long, slow, barely noticeable descent toward ever greater darkness, Satan finds an opportunity just as he found one in Judas Iscariot.

Our rage against the affairs of this world can also be a point of vulnerability. The great Christian writer, C. S. Lewis, described that path to spiritual destruction in his allegorical story, The Screwtape Letters (1940). He captures Satan instructing his nephew in the ways of spiritual warfare: “It is the cumulative effect of sin that draws the Man away from the Light and out into the Nothing ... The safest road to Hell is the gradual one, the gentle curves, soft underfoot, without turns, without signposts, without a roadmap. (The Screwtape Letters, p. 61)

Satan exploits fear, rage, even political contention and a pandemic to drive a wedge not only between persons, but within them. If your life of faith has been assailed by the world, the flesh, and the devil in this past year, we invite you to walk the Way of the Cross Beyond These Stone Walls this week.

We are posting on Monday of Holy Week instead of our usual Wednesday post day to present this special Holy Week post and a short list of six others for you to read and share in each day of Holy Week. The list begins in an hour of darkness and ends in the glory of Salvation.

+ + +

Satan at The Last Supper: Hours of Darkness & Light

Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’

Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands

Satan at The Last Supper: Hours of Darkness and Light

The central figures present before the Sacrament for the Life of the World are Jesus on the eve of Sacrifice and Satan on the eve of battle to restore the darkness.

The central figures present before the Sacrament for the Life of the World are Jesus on the eve of Sacrifice and Satan on the eve of battle to restore the darkness.

As I begin this eleventh Holy Week post behind These Stone Walls all the world is thrust under a shroud of darkness. A highly contagious and pernicious coronavirus threatens an entire generation of the most vulnerable among us on a global scale. Many Catholics face Holy Week without the visible support and consolation of a faith community. Many of our older loved ones face it entirely alone, separated from social networks and in dread of an unknown future darkness.

A week or so before writing this, I became aware of a social media exchange between two well-meaning Catholics. One had posted a suggestion that a formula for “exorcized holy water” would repel this new viral threat. The other cautioned how very dangerous such advice could be for those who would substitute it for clear and reasoned clinical steps to protect ourselves and others. I take a middle view. All the medical advice for social distancing and prevention must be followed, but spiritual protection should not be overlooked. Satan may not be the cause of all this, but he is certainly capable of manipulating it for our hopelessness and spiritual demise.

This “down time” might be a good time to reassess where we are spiritually. A sort of “new age” culture has infiltrated our Church in the misinterpretations of the Second Vatican Council since the 1960s. There is a secularizing trend to reduce Jesus to the nice things He said in the Beatitudes and beyond to the exclusion of who He was and is, and what Jesus has done to overcome the darkest of our dark. In a recent post, I asked a somewhat overused question with its answer in the same title: “What Would Jesus Do? He Would Raise Up Lazarus — and Us.” Without that answer, faith is reduced to just a series of quotes.

By design or not I do not know, but the current darkness drew me in this holiest of weeks to a scene in the Gospel that is easy to miss. There are subtle differences in the Passion Narratives of the Gospels which actually lend credence to the accounts. They reflect the testimony of eye witnesses rather than scripts. One of these subtle variations involves the mysterious presence of Satan in the story of Holy Week.

This actually begins early in the Gospel of Luke (Ch. 4) in an account I wrote about in “To Azazel: The Fate of a Church That Wanders in the Desert.” Placed in Luke’s Gospel after the Baptism of Jesus and God’s revelation that Jesus is God’s “Beloved Son,” Jesus is led by the Spirit into the desert wilderness for forty days. He is subjected there to a series of temptations by the devil. In the end, unable to turn Jesus from his path to light, “the devil departed from him until an opportune time.” (Luke 4:13)

That opportune time comes later in Luke’s Gospel, in Chapter 22. There, just as preparations for the Passover are underway, the conspiracy to kill Jesus arises among the chief priests and scribes. They must do this in the dead of night for Jesus is surrounded by crowds in the light of day. They need someone who will reveal where Jesus goes to rest at night and how they can identify him in the darkness.

Remember, there is no artificial light. The dark of night in First Century Palestine is a blackness like no one today has ever seen. This will require someone who has been slyly and subtly groomed by Satan, someone lured by a lust for money. This is the opportune time awaited by the devil in the desert:

“Then Satan entered into Judas called Iscariot, who was of the number of the Twelve. He went away and conferred with the chief priests and the captains how he might betray him to them. And they were glad, and engaged to give him money. So he agreed and sought an opportunity to betray him to them in the absence of the multitude.”

The Hour of Darkness

In Catholic tradition, the Passion Narrative from the Gospel of John is proclaimed on Good Friday. In that account, there is a striking difference in the chronology. Satan enters Judas, not in the preparations for Passover, but later the same day, shockingly at the Table of the Lord at the Last Supper on the eve of Passover:

“So when he dipped the morsel, Jesus gave it to Judas, the son of Simon Iscariot. Then, after the morsel, Satan entered into him. Jesus said to him, ‘What you are going to do, do quickly.’… So after receiving the morsel, he immediately went out, and it was night.”

Who could not be struck by those last few words, “and it was night”? They describe not only the time of day, but also the spiritual condition into which Judas has fallen. Judas and Satan are characters in this account from the Temptation of Jesus in the desert to the betrayal of Jesus in the hour of darkness. But darkness itself is also a character in this story. The word “darkness” appears 286 times in Sacred Scripture and “night” appears 365 times (which, ironically, is the exact number of nights in a year).

For their spiritual meaning, darkness and night are often used interchangeably. In St. John’s account of the betrayal by Judas, the fact that he “went out, and it was night” is highly symbolic. In the Hebrew Scriptures, our Old Testament, darkness was the element of chaos. The primeval abyss in the Genesis Creation story lay under chaos. God’s first act of creation was to dispel the darkness with the intrusion of light. “God separated the light from the darkness” (Genesis 1:4) which, in the view of Saint Augustine, was the moment Satan fell. In the Book of Job, God stores darkness in a chamber away from the path to light. God uses this imagery to challenge Job to know his place in spiritual relation to God:

“Have you, Job, commanded the dawn since your days began, and caused it to take hold of the skirts of the Earth for the wicked to be shaken out of it? … Do you know the way to the dwelling of light? Do you know the place of darkness?”

In the Book of Exodus, darkness is one of the plagues imposed upon Egypt. For the Prophet Amos (8:9) the supreme disaster is darkness at noon. In Isaiah (9:1) darkness implies defeat, captivity, oppression. It is the element of evil in which the wicked does its work (Ezekiel 8:12). It is the element of death, the grave, and the underworld (Job 10:21). In the Dead Sea Scrolls is a document called, “The Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness.” In the great Messianic Proclamation of Isaiah (9:2): “The People who walked in darkness have seen a great light.”

In the New Testament, the metaphors of light and darkness deepen. In the Gospel of Matthew (8:12, 22:13) sinners shall be cast into the darkness. In the Gospel of Mark (13:24) is the catastrophic darkness of the eschatological judgment. The Gospel of John is filled with metaphors of darkness and light. Earlier in the Gospel of John, Jesus confronts those who plot against him as under the influence of darkness and Satan:

“If God were your Father, you would love me, for I proceeded and came forth from God. I came not of my own accord, but He sent me. Why do you not understand what I say? It is because you cannot bear to hear my word. You are of your father, the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth because there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks according to his own nature, for he is a liar and the father of lies.”

I once wrote about the person of Judas and the great mystery of his betrayal, his life, and his end in “Judas Iscariot: Who Prays for the Soul of the Betrayer?” At the Passover meal and the Table of the Lord, he dipped his morsel only to exit into the darkness. In the original story of the Passover in Exodus (13:15-18) God required the lives of the firstborn sons of Pharoah and all Egypt to deliver His people from bondage. Now, in the Hour of Darkness set in motion by Satan and Judas, God will exact from Himself that very same price, and for the very same reason.

The Hour of Light

Biblical Hebrew had no word for “hour,” nor was such a term used as a measure of time. In the Roman and Greek cultures of the New Testament, the day was divided into twelve units. The term “hour” in the New Testament does not signify a measure of time but rather an expectation of an event. The “Hour of Jesus” is prominent in the Gospel of John and also mentioned in the Synoptic Gospels. Jesus is cited in John as saying that His Hour has not yet come (7:30 and 8:20). When it does come, it is the Hour in which the Son of Man is glorified (John 12:23; 17:1).

In the Gospel of Luke (22:53), Jesus said something ominous to the chief priests and captains of the Temple who came, led by Judas (and Satan), to arrest Him: “When I was with you day after day in the Temple, you did not lay hands on me but this is your hour, and the power of darkness.”

In all of Salvation History there has never been an Hour of Darkness without an Hour of Light. In the Passion of the Christ the two were not subsequent to each other, but rather parallel, arising from the same event rooted in sacrifice. This was the ultimate thwarting of Satan’s “opportune time.” Jesus, through sacrifice, did not just defeat Satan’s plan, but used its Hour of Darkness to bring about the Hour of Light.

Amazingly, “Light” and “Darkness” each appear exactly 288 times in Sacred Scripture. It is especially difficult to separate the darkness from the light in the Passion Narratives of the Gospel. Both are necessary for our redemption. Without darkness there is no sacrifice or even a need for sacrifice.

The Hour of Light began, not at Calvary, but at the Institution of the Eucharist at The Last Supper, the Passover meal with Jesus and His Apostles. The Words of Institution of the Eucharist are remarkably alike in substance and form in each of the Synoptic Gospels and in St. Paul’s First letter to the Corinthians (11:23).

The sacrificial nature of the Words of Institution and their intent at bringing about communion with God are most prominent in the oldest to come into written form, that of Saint Paul:

“For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus, on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it, and said, ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way also the chalice, after supper, saying, ‘This chalice is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.’ For as often as you eat this bread and drink the chalice, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.”

The enormity of this gift, the beginning of the Hour of Light, comes in the midst of words like “betrayal” and “death.” It is most interesting that the Gospel of John, which has Satan enter Judas at the Passover Table of the Lord, has no words for the formula of Institution of the Eucharist. But John clearly knows of it. The Gospel of John presents a clear theological allusion to the Eucharistic Feast in John 6:47-51:

“Truly, Truly I say to you, he who believes has eternal life. I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate manna in the desert and they died. This is the bread which comes down from heaven, that a man may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread which came down from heaven; if anyone eats this bread he will live for ever; and the bread which I shall give for the life of the world is my flesh.”

The term “will live forever” appears only three times in all of Sacred Scripture: twice in the above passage from John, and once in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures in Genesis 3:22. There, God expels Adam and Eve from Eden for attempting to be like God. It is a preventive measure in Genesis “lest they eat from the Tree of Life and live forever.” For John’s Gospel, what was denied to Adam is now freely given through the Sacrifice of Christ.

It is somewhat of a mystery why the Gospel of John places so beautifully his account of the Institution of the Eucharist there in Chapter 6 just after Jesus miraculously feeds the multitude with a few loaves of bread and a few fish, and then omits the actual Words of Institution from the Passover meal, the setting for The Last Supper in each of the other Gospels and in Saint Paul’s account.

Perhaps, on a most basic level, the Apostle John, beloved of the Lord, could not bring himself to include these words of sacrifice with Satan having just left the room. At a more likely level, John implies the Eucharist theologically through the entire text of his Gospel. In the end, after a theological and prayerful discourse at table, Jesus prays for the Church:

“When Jesus had spoken these words, he lifted up his eyes to heaven and said, ‘Father, the hour has come; glorify your Son that the Son may glorify you, since you have given him power over all flesh, to give eternal life to all whom you have given him. And this is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent.”

Now Comes the Hour of the Son of God, The Cross stood only for darkness and death until souls were illumined by the Cross of Christ. From the Table of the Lord, the lights stayed on in the Sanctuary Lamp of the Soul.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Take a time out from anxiety and isolation this Holy Week by spending time in the Hour of Light with these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

A Personal Holy Week Retreat at Beyond These Stone Walls

Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King But Caesar’

Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane

The Agony in the Garden, the First Sorrowful Mystery, is a painful scene in the Passion of Christ, but in each of the Synoptic Gospels the Apostles slept through it.

The Agony in the Garden, the First Sorrowful Mystery, is a painful scene in the Passion of Christ, but in each of the Synoptic Gospels the Apostles slept through it.

It seems so long ago now, but a few years back I wrote a post that stunned some TSW readers out of the doldrums of a long nap in the Garden of Gethsemane where, sooner or later, we will all spend some time. That post was “Pentecost, Priesthood, and Death in the Afternoon.”

It was about one of our friends, a middle-aged prisoner named Anthony, and his discovery of having terminal cancer. Anthony was one of the most irritating and obnoxious individuals I had ever met. He was the only prisoner I have ever thrown out of my cell with a demand that he never return. Very few people have had that kind of effect on me, but Anthony was masterful at it.

But then Anthony discovered that he was dying. As an unintended result of our “falling out” he believed that he could not come to me. He was Pornchai Moontri’s friend but the story of his impending doom was my comeuppance. I cannot forget the day that Pornchai told me, “You have to help Anthony. He is going to die and he doesn’t know how.” After a long sleep when the priest in me had succumbed too much to the prisoner, that was my awakening in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Over the next 18 months, Pornchai and I took care of Anthony for as long as we possibly could before handing him over to the prison version of hospice from where we would never see him again. But before that happened, Anthony became a Catholic, was received into the Church, and had a transformation of spirit that, in the midst of death, proclaimed an incomparable stress on life.

Pornchai and I were eyewitnesses to how all the things that once took priority in Anthony’s life just fell away. He became, in the end, like “Dismas, Crucified to the Right” of the Lamb of God. It seemed so ironic that it was his impending death that opened up for Anthony a world of faith, hope and trust that overcame all other forces at work in his life. In the end, I no longer, recognized the man I had once so disdained.

Not long after leaving us, Anthony died in the prison’s medical center where a small group of hospice volunteers took turns being with him around the clock. I once wrote of Anthony’s death, and of an event that shook our world back then, but it’s a story worth telling again. I told it at a brief memorial service for Anthony that was attended by about sixty prisoners, twice the normal for such things.

At the service in the prison chapel, those attending were invited to speak. So Pornchai nudged me and said, “Tell them about the book.” I told those in attendance that Anthony left this world having committed a second crime against the State of New Hampshire: an unreturned library book. The rest of the story generated a collective gasp.

The Library where I work has a computer system that tracks the 22,000 volumes from which prisoners can select and check out books. When a prisoner is released from prison without returning a book, an alert would come across the screen a week later to give us a last chance to find and retrieve a book left behind.

I had no knowledge that Anthony ever checked a book out of the Library. I never saw him there, and he never asked me for a book. But a week after he died, this appeared on my screen:

“Anthony Begin #76810 — Gone/Released — Heaven Is for Real”

The Agony in the Garden

Heaven is for real, but for it to be a reality for us required an Exodus from the slavery of sin and death. That second Exodus commenced in the Garden of Gethsemane, and in the course of it, God exacted from Himself the same price — the death of His Son — that he imposed upon Pharaoh to bring about the first Exodus.

The Biblical account of Jesus and His Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane opens the Passion Narrative of the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In the Gospel of John (18:1), the place is simply referred to as “across the Kidron Valley where there is a garden.” John, writing from a different tradition, cites only the betrayal by Judas there whereas the other Gospels precede that betrayal with the agony of Jesus at prayer.

Almost immediately preceding this in each of the Synoptic Gospels was the Institution of the Eucharist at what has been famously depicted by Leonardo Da Vinci as The Last Supper. This was the decisive turning point in Salvation History:

“Drink of it, all of you, for this is the blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins. I tell you I shall not drink again of this fruit of the vine until that day when I drink of it anew with you in my Father’s Kingdom.”

— Matthew 26: 28-29

Following this in the account of Saint Luke, Jesus addresses Peter about the spiritual warfare that is to come:

“‘Simon, Simon, behold, Satan demanded to have you that he might sift you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail; and when you have turned again, strengthen your brethren.’ And [Peter] said to him, ‘Lord, I am ready to go with you to prison and to death.’”

— Luke 22:31-34

Peter’s “readiness” for prison and for death will soon become an issue. From here the scene moves to the Mount of Olives where Jesus went to pray “as was His custom” (Luke 22:39).

Only the Gospels of Matthew and Mark name the place “Gethsemane.” Once there, Jesus withdrew from His disciples to pray. As you already know, the suffering and death he now faced would be set in motion by the betrayal of Judas who provided “the more opportune time” that Satan awaited when the Temptation of Christ in the desert failed (Luke 4:13), a scene depicted in “To Azazel: The Fate of a Church That Wanders in the Desert.”

Jesus, fully human in his suffering by God’s design, recoils not only from the image of suffering he knows to be upon Him, but also by the weight of the Apostolic betrayal just moments away. The betrayal by Judas is intensified by the dreadful weight of humanity’s sin for which Jesus is offered up as the Scapegoat — the Sacrificial Lamb of God — for the sins of all humanity.

For Hebrew ears, the account of Jesus at Gethsemane is a mirror image in reverse of a scene that occurred at this very same site 1,000 years earlier. It was a story not of a son obedient unto death, but of a son who betrayed his father. It was the agony of King David and his flight from his son, Absolom, and his traitorous revolt. As David learned that his trusted counselor, Ahithophel, had betrayed him in league with Absolom…

“David went up the ascent of the Mount of Olives, weeping as he went, with his head covered and walking barefoot, and all the people who were with him covered their heads and went up, weeping as they went. David was told that Ahithophel was one of the conspirators with Absolom.”

— 2 Samuel 15:30-31

And, as with Judas 1,000 years later, Ahithophel hanged himself when the consequences of his betrayal weighed upon him.

In Saint Matthew’s account of the Gethsemane scene (26:37), Jesus left His disciples and brought Peter, James and John with Him to the place of prayer. Note that Peter, James and John witnessed Jesus raise the daughter of Jairus from death (Mark 5:37) and they were also witnesses to His Transfiguration in the presence of Moses and Elijah that I wrote of during this Lent in “Turmoil in Rome and the Transfiguration of Christ.”

In the Gospel of Luke (22:31ff) Jesus is alone and apart from the others as He prays in agony in the face of death: “Father if you are willing, remove this chalice from me; nevertheless not my will but yours be done.” I cannot tell you how often I have prayed that same prayer in the last 25 years. I pray it still.

In the Gospel, God answers the prayer of Jesus, not by removing the suffering, for His suffering is to be our Exodus, but by strengthening Him to endure it. And He will endure it unto death:

“There appeared to him an angel from heaven to strengthen him. And being in agony, he prayed more earnestly; and his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down upon the ground.”

— Luke 22:43

In each of the Gospel accounts, Jesus returned to His disciples to discover that they have all slept through His agony. None were there to console Him except the angel sent from heaven while humanity slept.

Consoling the Heart of Jesus

The Gospel of Saint Mark presents a more vivid account of the inner suffering that betrayal and death brought to the heart of Jesus. Mark describes that Jesus “began to be greatly distressed and troubled” (Mark 14:33). The Greek of Mark’s Gospel used the terms έκθαμβεῖσθαι and άδημονεῖν which vividly express in Greek the depth of distress and anxiety that came upon Him. The comfort the angel brings is reminiscent of Psalm 42:

“Why are you cast down O my soul, and why are you disquieted within me? Hope in God; for I shall again praise him, my help and my God.”

— Psalm 42:12

The coming betrayal by Judas marks the climax of the ministry of Jesus who has left hints throughout the Gospel of Mark:

“And he began to teach them that the Son of man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again. And he said this plainly.”

— Mark 8:31

“The Son of man will be delivered into the hands of men, and they will kill him, and when he is killed, after three days he will rise.”

— Mark 9:31

“Behold, we are going up to Jerusalem, and the Son of man will be delivered to the chief priests and the scribes, and they will condemn him to death, and deliver him to the Gentiles, and they will mock him, and spit on him, and scourge him, and kill him, and after three days he will rise.”

— Mark 10:33-34

So how do we, His disciples by Baptism and by the fidelity we claim, how do we console the heart of Jesus at Gethsemane? For the answer, I am indebted to Father Michael Gaitley, M.I.C. for his profound book, Consoling the Heart of Jesus which was the text for a six-week course offered here by the Marians of the National Shrine of The Divine Mercy.

Like many, I believe I learn the most from Sacred Scripture when the circumstances of my life force me to live it. So picking up this book for the first time, I asked myself, “How can I console Jesus, who is happy in Heaven, while I am stuck in this hellhole called prison?” That’s what Pornchai Moontri called it in these pages in his post, “Imprisoned by Walls, Set Free by Wood.”

Father Gaitley has an answer called “Retroactive Consolation” that comes from the theology of Pope Pius XI and the Dominican theologian, Réginald Marie Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P. whom Father Gaitley quotes:

“During his earthly life and particularly while in Gethsemane, Jesus suffered from all future acts of profanation and ingratitude. He knew them in detail with a superior intuition that governed all times… Thus his suffering encompassed the present instant and extended to future centuries. ‘This drop of blood I shed for you.’ So in the Garden of Olives, Jesus suffered for all, and for each of us in particular.”

— Consoling the Heart of Jesus, P. 394

So, if His suffering is projected into the future, how can our consolation of Him at Gethsemane become retroactive into the past? What will awaken us from our sleep in the Garden of Gethsemane? Jesus Himself provides that answer, and it has something to do with our story about Anthony that began this post. It is laid out powerfully in the Gospel of Matthew:

“Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and care for you?’ And the King will answer them, ‘Truly I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these, you did it to me.’”

— Matthew 25:37-40

Now

“Arise. Let us be going. See, my betrayer is at hand.”

— Matthew 26:46

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Please share this Holy Week post with your contacts on Facebook and other social media. To prepare for a meaningful Holy Week and Easter, you may also like these other posts from along the Way of the Cross at Beyond These Stone Walls :

A Personal Holy Week Retreat at Beyond These Stone Walls

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’

Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands

Simon of Cyrene at Calvary: Compelled to Carry the Cross

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

The Passion of the Christ has historical meaning on its face, but a far deeper story lies beneath where the threads of faith and history connect to awaken the soul.

There are few things in life that a priest could hear with greater impact than what was revealed to me in a recent letter from a reader of These Stone Walls. After stumbling upon TSW several months ago, the writer began to read these pages with growing interest. Since then, she has joined many to begin the great adventure of the two most powerful spiritual movements of our time: Marian Consecration and Divine Mercy. In a recent letter she wrote, “I have been a lazy Catholic, just going through the motions, but your writing has awakened me to a greater understanding of the depths of our faith.”

I don’t think I actually have much to do with such awakenings. My writing doesn’t really awaken anyone. In fact, after typing last week’s post, I asked my friend, Pornchai Moontri to read it. He was snoring by the end of page two. I think it is more likely the subject matter that enlightens. The reader’s letter reminded me of the reading from Saint Paul’s Letter to the Ephesians read by Pornchai a few weeks ago, quoted in “De Profundis: Pornchai Moontri and the Raising of Lazarus”:

“Awake, O sleeper, and rise from the dead, and Christ will give you light.”

I may never understand exactly what These Stone Walls means to readers and how they respond. That post generated fewer comments than most, but within just hours of being posted, it was shared more than 1,000 times on Facebook and other social media.

Of 380 posts published thus far on These Stone Walls, only about ten have generated such a response in a single day. Five of them were written in just the last few months in a crucible described in “Hebrews 13:3 Writing Just This Side of the Gates of Hell.” I write in the dark. Only Christ brings light.

Saint Paul and I have only two things in common — we have both been shipwrecked, and we both wrote from prison. And it seems neither of us had any clue that what we wrote from prison would ever see the light of day, let alone the light of Christ. There is beneath every story another story that brings more light to what is on the surface. There is another story beneath my post, “De Profundis.” That title is Latin for “Out of the Depths,” the first words of Psalm 130. When I wrote it, I had no idea that Psalm 130 was the Responsorial Psalm for Mass before the Gospel account of the raising of Lazarus:

“Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord!

Lord hear my voice!

Let your ears be attentive

to my voice in supplication…

”I wait for the Lord, my soul waits,

and I hope in his word;

my soul waits for the Lord

more than sentinels wait for the dawn,

more than sentinels wait for the dawn.”

Notice that the psalmist repeats that last line. Anyone who has ever spent a night lying awake in the oppression of fear or dark depression knows the high anxiety that accompanies a long lonely wait for the first glimmer of dawn. I keep praying that Psalm — I have prayed it for years — and yet Jesus has not seen fit to fix my problems the way I want them fixed. Like Saint Paul, in the dawn’s early light I still find myself falsely accused, shipwrecked, and unjustly in prison.

Jesus also prayed the Psalms. In a mix of Hebrew and Aramaic, he cries out from the Cross, “Eli, Eli làma sabach-thàni?” It is not an accusation about the abandonment of God. It is Psalm 22, a prayer against misery and mockery, against those who view the cross we bear as evidence of God’s abandonment. It is a prayer against the use of our own suffering to mock God. It’s a Psalm of David, of whom Jesus is a descendant by adoption through Joseph:

“Eli, Eli làma sabach-thàni?

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are You so far from my plea,

from the words of my cry? …

… All who see me mock at me;

they curse me with parted lips,

they wag their heads …

Indeed many dogs surround me,

a pack of evildoers closes in upon me;

they have pierced my hands and my feet.

I can count all my bones …

They divide my garments among them;

for my clothes they cast lots.”

So maybe, like so many in this world who suffer unjustly, we have to wait in hope simply for Christ to be our light. And what comes with the light? Suffering does not always change, but its meaning does. Take it from someone who has suffered unjustly. What suffering longs for most is meaning. People of faith have to trust that there is meaning to suffering even when we cannot detect it, even as we sit and wait to hear, “Upon the Dung Heap of Job: God’s Answer to Suffering.”

The Passion of the Christ

Last year during Holy Week, two Catholic prisoners had been arguing about why the date of Easter changes from year to year. They both came up with bizarre theories, so one of them came to ask me. I explained that in the Roman Church, Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox (equinox is from the Latin, “equi noctis,” for “equal night”). The prisoner was astonished by my ignorance and said, “What BS! Easter is forty days after Ash Wednesday!”

Getting to the story beneath the one on the surface is important to understand something as profound as the events of the Passion of the Christ. You may remember from my post, “De Profundis,” that Jesus said something perplexing when he learned of the illness of Lazarus:

“This illness is not unto death; it is for the glory of God, so that the Son of God may be glorified by means of it”

The irony of this is clearer when you see that it was the raising of Lazarus that condemned Jesus to death. The High Priests were deeply offended, and the insult was an irony of Biblical proportions (no pun intended). Immediately following upon the raising of Lazarus, “the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered the council” (the Sanhedrin). They were in a panic over the signs performed by Jesus. “If he goes on like this,” they complained, “the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place (the Jerusalem Temple) and our nation” (John 11 47-48).

The two major religious schools of thought in Judaism in the time of Jesus were the Pharisees and the Sadducees. Both arose in Judaism in the Second Century B.C. and faded from history in the First Century A.D. At the time of Jesus, there were about 6,000 Pharisees. The name, “Pharisees” — Hebrew for “Separated Ones” — came as a result of their strict observance of ritual piety, and their determination to keep Judaism from being contaminated by foreign religious practices. Their hostile reaction to the raising of Lazarus had nothing to do with the raising of Lazarus, but rather with the fact that it occurred on the Sabbath which was considered a crime.

Jesus actually had some common ground with the Pharisees. They believed in angels and demons. They believed in the human soul and upheld the doctrine of resurrection from the dead and future life. Theologically, they were hostile to the Sadducees, an aristocratic priestly class that denied resurrection, the soul, angels, and any authority beyond the Torah.

Both groups appear to have their origin in a leadership vacuum that occurred in Jerusalem between the time of the Maccabees and their revolt against the Greek king Antiochus Epiphanies who desecrated the Temple in 167 B.C. It’s a story that began Lent on These Stone Walls in “Semper Fi! Forty Days of Lent Giving Up Giving Up.”

The Pharisees and Sadducees had no common ground at all except a fear that the Roman Empire would swallow up their faith and their nation. And so they came together in the Sanhedrin, the religious high court that formed in the same time period the Pharisees and Sadducees themselves had formed, in the vacuum left by the revolt that expelled Greek invaders and their desecration of the Temple in 165 B.C.

The Sanhedrin was originally composed of Sadducees, the priestly class, but as common enemies grew, the body came to include Scribes (lawyers) and Pharisees. The Pharisees and Sadducees also found common ground in their disdain for the signs and wonders of Jesus and the growth in numbers of those who came to believe in him and see him as Messiah.

The high profile raising of Lazarus became a crisis for both, but not for the same reasons. The Pharisees feared drawing the attention of Rome, but the Sadducees felt personally threatened. They denied any resurrection from the dead, and could not maintain religious influence if Jesus was going around doing just that. So Caiaphas, the High Priest, took charge at the post-Lazarus meeting of the Sanhedrin, and he challenged the Pharisees whose sole concern was for any imperial interference from the Roman Empire. Caiaphas said,

“You know nothing at all. You do not understand that it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people, so that the whole nation should not perish”

The Gospel of John went on to explain that Caiaphas, being High Priest, “did not say this of his own accord, but to prophesy” that Jesus was to die for the nation, “and not for the nation only, but, to gather into one the children of God” (John 11: 41-52). From that moment on, with Caiaphas being the first to raise it, the Sanhedrin sought a means to put Jesus to death.

Caiaphas presided over the Sanhedrin at the time of the arrest of Jesus. In the Sanhedrin’s legal system, as in our’s today, the benefit of doubt was supposed to rest with the accused, but … well … you know how that goes. The decision was made to find a reason to put Jesus to death before any legal means were devised to actually bring that about.

Behold the Man!

The case found its way before Pontius Pilate, the Roman Prefect of Judea from 25 to 36 A.D. Pilate had a reputation for both cruelty and indecision in legal cases before him. He had previously antagonized Jewish leaders by setting up Roman standards bearing the image of Caesar in Jerusalem, a clear violation of the Mosaic law barring graven images.

All four Evangelists emphasize that, despite his indecision about the case of Jesus, Pilate considered Jesus to be innocent. This is a scene I have written about in a prior Holy Week post, “Behold the Man as Pilate washes His Hands.”

On the pretext that Jesus was from Galilee, thus technically a subject of Herod Antipas, Pilate sent Jesus to Herod in an effort to free himself from having to handle the trial. When Jesus did not answer Herod’s questions (Luke 23: 7-15) Herod sent him back to Pilate. Herod and Pilate had previously been indifferent, at best, and sometimes even antagonistic to each other, but over the trial of Jesus, they became friends. It was one of history’s most dangerous liaisons.

The trial before Pilate in the Gospel of John is described in seven distinct scenes, but the most unexpected twist occurs in the seventh. Unable to get around Pilate’s indecision about the guilt of Jesus in the crime of blasphemy, Jewish leaders of the Sanhedrin resorted to another tactic. Their charge against Jesus evolved into a charge against Pilate himself: “If you release him, you are no friend of Caesar” (John 19:12).

This stopped Pilate in his tracks. “Friend of Caesar” was a political honorific title bestowed by the Roman Empire. Equivalent examples today would be the Presidential Medal of Freedom bestowed upon a philanthropist, or a bishop bestowing the Saint Thomas More Medal upon a judge. Coins of the realm depicting Herod the Great bore the Greek insignia “Philokaisar” meaning “Friend of Caesar.” The title was politically a very big deal.

In order to bring about the execution of Jesus, the religious authorities had to shift away from presenting Jesus as guilty of blasphemy to a political charge that he is a self-described king and therefore a threat to the authority of Caesar. The charge implied that Pilate, if he lets Jesus go free, will also suffer a political fallout.

So then the unthinkable happens. Pilate gives clemency a final effort, and the shift of the Sadducees from blasphemy to blackmail becomes the final word, and in pronouncing it, the Chief Priests commit a far greater blasphemy than the one they accuse Jesus of:

“Shall I crucify your king? The Chief Priests answered, ‘We have no king but Caesar.”

Then Pilate handed him over to be crucified.

+ + +

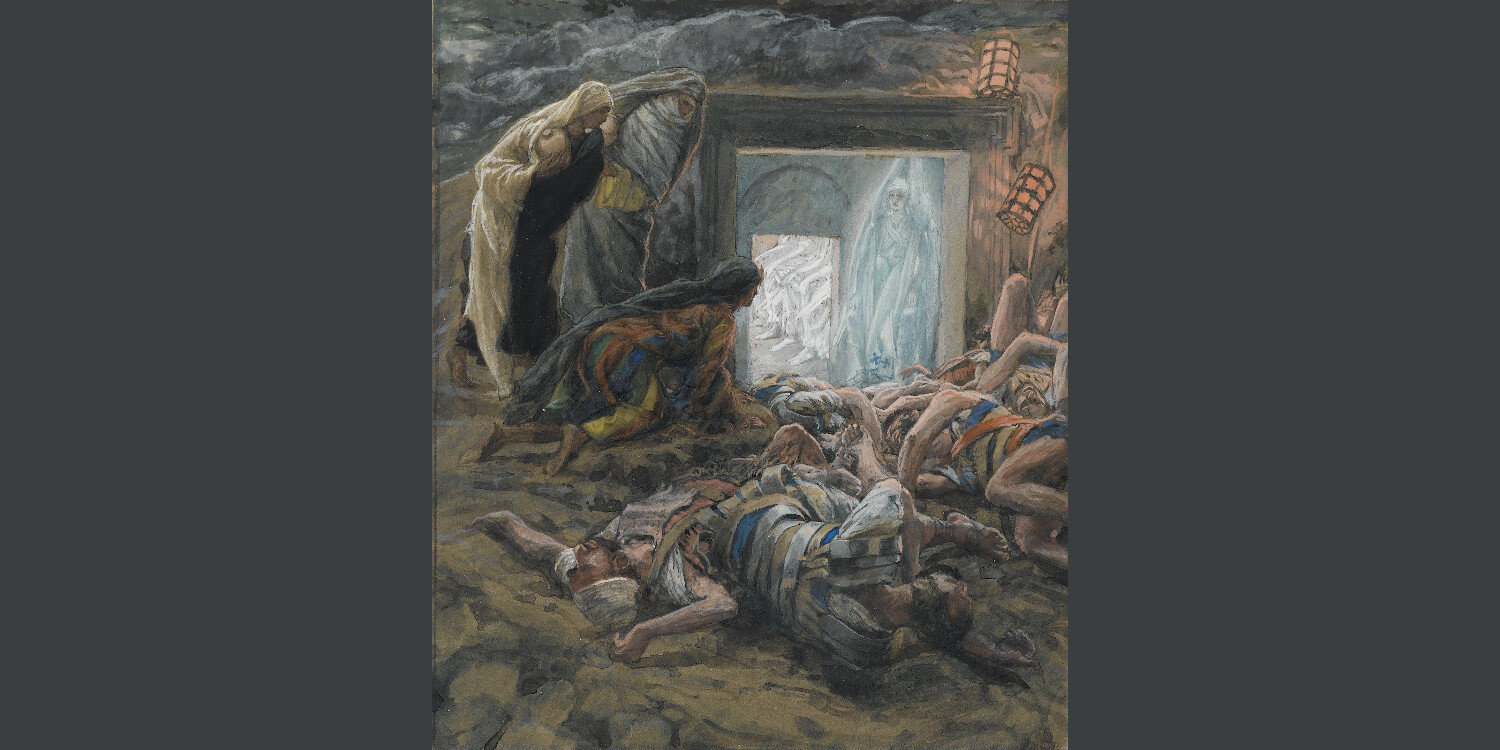

Mary Magdalene: Faith, Courage, and an Empty Tomb

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous and noble woman, an apostle to the Apostles.

History unjustly sullied her name without evidence, but Mary Magdalene emerges from the Gospel a faithful, courageous and noble woman, an apostle to the Apostles.

As an imprisoned priest, a communal celebration of the Easter Triduum is not available to me. My celebration of this week is for the most part limited to a private reading of the Roman Missal. Still, over the five-plus years that I have been writing for These Stone Walls, I have always agonized about Holy Week posts. I feel a special duty to contribute what little I can to the Church’s volume of reflection on the meaning of this week.

Though I have little in the way of resources beyond what is in my own mind, I feel an obligation in this of all weeks to “get it right,” and leave something a reader might return to. So I have focused in past Holy Week posts not so much on the meaning of the events of the Passion of the Christ, but on the characters central to those events. In so doing, I have developed a rather special kinship with some of them.

I hope readers will spend some time with them this week by revisiting my Holy Week tributes to “Simon of Cyrene, Compelled to Carry the Cross,” and “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” I wrote a follow-up to that one in a subsequent Holy Week post entitled, “Pope Francis, the Pride of Mockery, and the Mockery of Pride.” Last year in Holy Week, I visited a haunting work of art fixed upon the wall of my prison cell in “Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands.”

Lifting these characters out of the lines of the Gospel into the light of my quest to know them has enhanced a sense of solidarity with them. This has never been truer than it is for the subject of this year’s TSW Holy Week post. Any believer whose reputation has been overshadowed by innuendos of a past, anyone who stands in possession of a truth that must be told, but is denied the social status to be believed will marvel at the faith and courage of Mary Magdalene.

Her Demon Haunted World

First, a word about language. You might note that I always use the Aramaic term, “Golgotha,” instead of the more familiar “Calvary” for the place where Jesus was crucified. Aramaic is closely related to Hebrew. It became the language of the Middle East sometime after the fall of Nineveh in 612 B.C., and was the language of Palestine at the time of Jesus. Jesus spoke in Aramaic, and so did his disciples.

The Aramaic word, “Golgotha” means “place of the skull.” When the Roman Empire occupied Palestine in 63 B.C., it used that place for crucifixions. It isn’t certain whether that is the origin of the name “Golgotha” or whether the hill resembles a skull from some vantage point. The Gospels were written in Greek, so the Aramaic “Golgotha” was translated “Kranion,” Greek for “skull.” Then in the Fourth and early Fifth Century, Saint Jerome translated the Greek Gospels into Latin using the term, “Calvoriae Locus” for “Place of the Skull.” That’s how the name “Calvary” entered Christian thought.

Mary Magdalene is one of only two figures in the Gospel to have been present with Jesus during his public ministry, at the foot of the Cross at Golgotha, and in his resurrection appearances at and after the empty tomb. The sole other figure was John, the Beloved Disciple. Mary the Mother of Jesus was also present at the Cross, but there is no mention of her at the empty tomb. In the Gospel of Saint Luke, the Twelve were with Jesus during his public ministry …

“… also some women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities, Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward, and Suzanna, and many others who provided for them out of their means.”

The presence of these women openly challenged Jewish customs and mores of the time which discouraged men from associating with women in public. Add to this the fact that these particular women “had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities” could have set the community abuzz with whispers at their presence with Jesus. In the Gospel of John (4:27), the Apostles came upon Jesus talking with a woman of Samaria at Jacob’s well, and they “marveled that he was talking with a woman.”

A revelation that seven demons had gone out of Mary Magdalene is in no way suppressed by the Gospel writer. On the contrary, it seems the basis of her undying fidelity to the Lord. The Gospel of Saint Mark adds that account in the most unlikely place — the one place where Mary’s credibility seems a necessity, the first Resurrection appearance:

“Now when he rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene from whom he had cast out seven demons. She went and told those who had been with him, as they mourned and wept. But when they heard he was alive and had been seen by her, they would not believe it.”

In all four of the Gospel accounts, it was Mary Magdalene who first discovered and announced the empty tomb, and in all four places the announcement sowed doubt, and even some propaganda. In the Gospel of Matthew (28:1-10), “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to the tomb … .” There they were met by an angel who instructed them, “Go quickly and tell his disciples that he has risen from the dead and behold, he is going before you to Galilee.”

Then, in Saint Matthew’s account, Jesus appeared to them on the road and said, “Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brethren to go to Galilee, and there they will see me.” Put yourself in Mary Magdalene’s shoes. She, from whom he cast out seven demons; she, who watched him die a gruesome death, is to find Peter, tell this story, and expect to be believed?

Immediately after in the Gospel of Matthew, the Roman guards went to Caiaphas the High Priest with their own story of what they witnessed at the tomb. Like the thirty pieces of silver used to bribe Judas, Caiaphas paid the guards to spread an alternate story:

“Go report to Pilate that Jesus’ disciples came and stole his body while the guards slept…’ This story has been spread among the Jews even to this day”

Apostle to the Apostles

It makes perfect sense. I, too, have seen “truth” reinvented when there is money involved. Remember that Mary Magdalene is a woman alone, with demons in her past, and she must convey her amazing account to men. So suspect is she as a source that even the early Church overlooked her witness. When Saint Paul related the Resurrection appearances to the Church at Corinth about twenty years later, he omitted Mary Magdalene entirely:

“He appeared to Cephas [the Greek name for Peter], then to the Twelve, then to more than 500 brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James then to all the Apostles. Then last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared to me, for I am the least of the Apostles.”

Saint Paul lists six appearances of Jesus during the forty days between the Resurrection and the Ascension. One of those appearances “to more than 500” appears in none of the Gospel accounts. Saint Paul likely omitted the fact that it was Mary Magdalene from whom news of the Resurrection first arose, and to whom the Risen Christ first appeared, because at that time in that culture, women could not give sworn testimony.

And remember that there was another matter Mary Magdalene had to reconcile before conveying her news. It is the elephant in the upper room. She must not only tell her story to men, but to men who fled Golgotha while she remained. Among all in that room, only Mary Magdalene and the Beloved Disciple John saw Christ die. Peter, their leader, denied knowing Jesus and remained below, listening to a cock crow.

I have imagined another version of Mary Magdalene’s empty tomb report to Peter. I imagined reading it between the lines, but of course it isn’t really there. Still, it’s the version that would have made the most human sense: Mary Magdalene burst into an upper room where the Apostles hid “for fear of the Jews.” She summoned the courage to look Peter in the eye.

Mary M.: “I have good news and not-so-good news.”

Peter: “What’s the good news?”

Mary M.: “The Lord has risen and I have seen him!”

Peter: “And the not-so-good good news?”

Mary M.: “He’s on his way here and he’d like a word with you about last Friday.”

Of course, nothing like that happened. The words of Jesus to Peter about “last Friday” correct his three-time denial with a three-time commission of the risen Christ to “feed my sheep.” The Gospel message is built upon values and principles that challenge all our basest instincts for retribution and justice. The Gospel presents God’s justice, not ours.

Of the four accounts of the Crucifixion and the Resurrection Appearances, the Gospel of John conveys perhaps the most painful, beautiful, and stunning portrait of Mary Magdalene, all written between the lines:

“Standing by the Cross of Jesus were his mother, his mother’s sister [possibly Salome, mother of James and John], Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene.”

Also standing there is John, the Beloved Disciple, and Mary Magdalene becomes a witness to one of the most profound scenes of Sacred Scripture. Jesus addressed his mother from the Cross, “Woman, behold your son.” Is it a reference to himself or to the young man standing next to his mother? Is it both? Standing just feet away, the woman from whom he once cast out seven demons is fixated by what is taking place here. “Behold your Mother!” he says among his last words from the Cross, bestowing upon John — and all of us by extension — the gifts of grace and the care of his mother.

“Woman, Why Are You Weeping?”

“From that point on, John took her into his home,” and we took her into the home of our hearts. Mary Magdalene could barely have dealt with this shattering scene as her Deliverer died before her eyes when, on the morning of the first day of the week, she stood weeping outside his empty tomb. “Woman, why are you weeping?” Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI wrote of this scene from the Gospel of John in his beautifully written book, Jesus of Nazareth: Holy Week (Ignatius Press, 2011):

“Now he calls her by name: ‘Mary!’ Once again she has to turn, and now she joyfully recognizes the risen Lord whom she addresses as ‘Rabboni,’ meaning ‘teacher.’ She wants to touch him, to hold him, but the Lord says to her, “Do not hold me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father” (John 20:17). This surprises us…. The earlier way of relating to the earthly Jesus is no longer possible.”

Hippolytus of Rome, a Third Century Father of the Church, called Mary Magdalene an “apostle to the Apostles.” Then in the Sixth Century, Pope Gregory the Great merged Mary Magdalene with the unnamed “sinful woman” who anointed Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (7:37), and with Mary of Bethany who anointed him in the Gospel of John (12:3). This set in motion any number of conspiracy theories and unfounded legends about Jesus and Mary Magdalene that had no basis in fact.

The revisionist history in popular books like The Da Vinci Code, and other novels by New Hampshire author Dan Brown, was contingent upon Mary Magdalene and these two other women being one and the same. The Gospel provides no evidence to support this, a fact the Church now accepts and promotes. This faithful and courageous woman at the Empty Tomb was rescued not only from her demons, but from the distortions of history.

“While up to the moment of Jesus’ death, the suffering Lord had been surrounded by nothing but mockery and cruelty, the Passion Narratives end on a conciliatory note, which leads into the burial and the Resurrection. The faithful women are there…. Gazing upon the Pierced One and suffering with him have now become a fount of purification. The transforming power of Jesus’ Passion has begun.”

+ + +

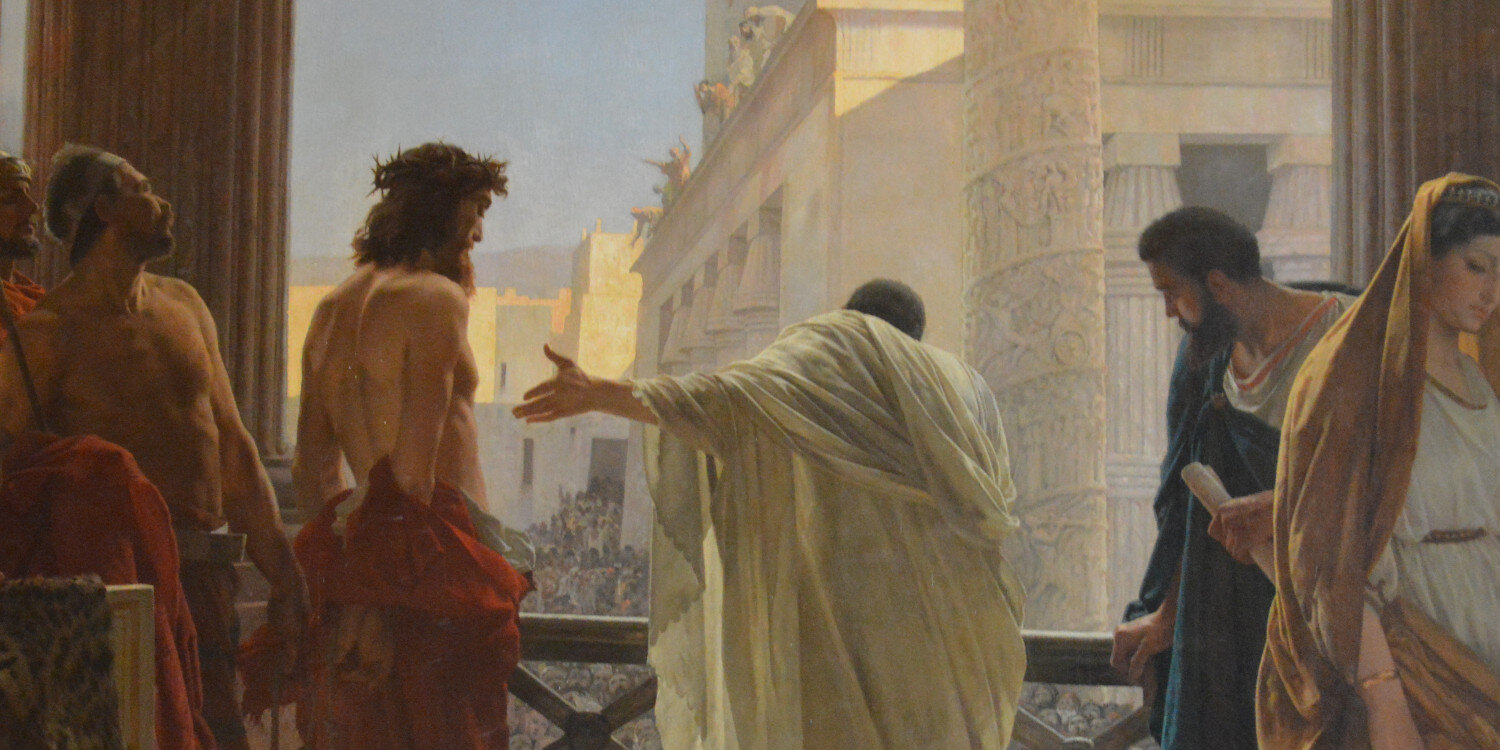

Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands

“Ecce Homo!” An 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri depicts a moment woven into the fabric of salvation history, and into our very souls.

“Ecce Homo!” An 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri depicts a moment woven into the fabric of salvation history, and into our very souls.

“So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd saying, ‘I am innocent of this righteous man’s blood.’”

A now well known Wall Street Journal article, “The Trials of Father MacRae” by Dorothy Rabinowitz (May 10, 2013) had a photograph of me — with hair, no less — being led in chains from my 1994 trial. When I saw that photo, I was drawn back to a vivid scene that I wrote about during Holy Week two years ago in “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” My Holy Week post began with the scene depicted in that photo and all that was to follow on the day I was sent to prison. It was the Feast of Saint Padre Pio, September 23, 1994, but as I stood before Judge Arthur Brennan to hear my condemnation, I was oblivious to that fact.

Had that photo a more panoramic view, you would see two men shuffling in chains ahead of me toward a prison-bound van. They had the misfortune of being surrounded by clicking cameras aimed at me, and reporters jockeying for position to capture the moment to feed “Our Catholic Tabloid Frenzy About Fallen Priests.” That short walk to the prison van seemed so very long. Despite his own chains, one of the two convicts ahead of me joined the small crowd in mockery of me. The other chastised him in my defense.

Writing from prison 18 years later, in Holy Week 2012, I could not help but remember some irony in that scene as I contemplated the fact of “Dismas, Crucified to the Right.” That post ended with the brief exchange between Christ and Dismas from their respective crosses, and the promise of Paradise on the horizon in response to the plea of Dismas: “Remember me when you come into your kingdom.” This conversation from the cross has some surprising meaning beneath its surface. That post might be worth a Good Friday visit this year.

But before the declaration to Dismas from the Crucified Christ — “Today, you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43) — salvation history required a much more ominous declaration. It was that of Pontius Pilate who washed his hands of any responsibility for the Roman execution of the Christ.

Two weeks ago, in “What if the Prodigal Son Had No Father to Return To?”, I wrote of my fascination with etymology, the origins of words and their meanings. There is also a traceable origin for many oft-used phrases such as “I wash my hands of it.” That well-known phrase came down to us through the centuries to renounce responsibility for any number of the injustices incurred by others. The phrase is a direct allusion to the words and actions of Pontius Pilate from the Gospel of Saint Matthew (27: 24).

Before Pilate stood an innocent man, Jesus of Nazareth, about to be whipped and beaten, then crowned with thorns in mockery of his kingship. Pilate had no real fear of the crowd. He had no reason to appease them. No amount of hand washing can cleanse from history the stain that Pilate tried to remove from himself by this symbolic washing of his hands.

This scene became the First Station of the Cross. At the Shrine of Lourdes the scene includes a boy standing behind Pilate with a bowl of water to wash away Pilate’s guilt. My friend, Father George David Byers sent me a photo of it, and a post he once wrote after a pilgrimage to Lourdes:

“Some of you may be familiar with ‘The High Stations’ up on the mountain behind the grotto in Lourdes, France. The larger-than-life bronze statues made vivid the intensity of the injustice that is occurring. In the First Station, Jesus, guarded by Roman soldiers, is depicted as being condemned to death by Pontius Pilate who is about to wash his hands of this unjust judgment. A boy stands at the ready with a bowl and a pitcher of water so as to wash away the guilt from the hands of Pilate . . . Some years ago a terrorist group set off a bomb in front of this scene. The bronze statue of Pontius Pilate was destroyed . . . The water boy is still there, eager to wash our hands of guilt, though such forgiveness is only given from the Cross.”

The Writing on the Wall

As that van left me behind these stone walls that day over thirty years ago, the other two prisoners with me were sent off to the usual Receiving Unit, but something more special awaited me. I was taken to begin a three-month stay in solitary confinement. Every surface of the cell I was in bore the madness of previous occupants. Every square inch of its walls was completely covered in penciled graffiti. At first, it repulsed me. Then, after unending days with nothing to contemplate but my plight and those walls, I began to read. I read every scribbled thought, every scrawled expletive, every plea for mercy and deliverance. I read them a hundred times over before I emerged from that tomb three months later, still sane. Or so I thought.

When I read “On the Day of Padre Pio, My Best Friend Was Stigmatized,” Pornchai Maximilian Moontri’s guest post from Thailand, I wondered how he endured solitary confinement that stretched for year upon year. “Today as I look back,” he wrote, “I see that even then in the darkness of solitary confinement, Christ was calling me out of the dark.” It’s an ironic image because one of the most maddening things about solitary confinement is that it’s never dark. Intense overhead lights are on 24/7.

The darkness of solitary confinement he described is only on the inside, the inside of a mind and soul, and it’s a pitch blackness that defies description. My psyche was wounded, at best, after three months. I cannot describe how Pornchai endured this for many years. But he did, and no doubt those who brought it about have since washed their hands of it.

For me, once out of solitary confinement, the writing on the walls took on new meaning. In “Angelic Justice: St Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed,” I described a section of each cell wall where prisoners are allowed to post the images that give meaning and hope to their lives. One wall in each cell contains two painted rectangles, each barely more than two by four feet, and posted within them are the sole remnant of any individualism in prison. You can learn a lot about a man from that finite space on his wall.

When I was moved into this cell, Pornchai’s wall was empty, and mine remained empty as well. Once this blog began in 2009, however, readers began to transform our wall without realizing it. Images sent to me made their way onto the wall, and some of the really nice ones somehow mysteriously migrated over to Pornchai’s wall. A very nice Saint Michael icon spread its wings and flew over to his side one day. That now famous photo of Pope Francis with a lamb placed on his shoulders is on Pornchai’s wall, and when I asked him how my Saint Padre Pio icon managed to get over there, he muttered something about bilocation.

Ecce Homo!

One powerful image, however, has never left its designated spot in the very center of my wall. It’s a five-by-seven inch card bearing the 1871 painting, “Ecce Homo!” — “Behold the Man!” — by the Swiss-born Italian artist, Antonio Ciseri. It was sent to me by a reader during Holy Week a few years ago. The haunting image went quickly onto my cell wall where it has remained since. The Ciseri painting depicts a scene that both draws me in and repels me at the same time.

On one dark day in prison, I decided to take it down from my wall because it troubles me. But I could not, and it took some time to figure out why. This scene of Christ before Pilate captures an event described vividly in the Gospel of Saint John (19:1-5). Pilate, unable to reason with the crowd has Jesus taken behind the scenes to be stripped and scourged, a mocking crown of thorns thrust upon his head. The image makes me not want to look, but then once I do look, I have a hard time looking away.

When he is returned to Pilate, as the scene depicts, the hands of Christ are bound behind his back, a scarlet garment in further mockery of his kingship is stripped from him down to his waist. His eyes are cast to the floor as Pilate, in fine white robes, gestures to Christ with his left hand to incite the crowd into a final decision that he has the power to overrule, but won’t. “Behold the Man!” Pilate shouts in a last vain gesture that perhaps this beating and public humiliation might be enough for them. It isn’t.

I don’t want to look, and I can’t look away because I once stood in that spot, half naked before Pilate in a trial-by-mob. On that day when I arrived in prison, before I was thrown into solitary confinement for three months, I was unceremoniously doused with a delousing agent, and then forced to stand naked while surrounded by men in riot gear, Pilate’s guards mocking not so much what they thought was my crime, but my priesthood. They pointed at me and laughed, invited me to give them an excuse for my own scourging, and then finally, when the mob was appeased, they left me in the tomb they prepared, the tomb of solitary confinement. Many would today deny that such a scene ever took place, but it did. It was thirty years ago. Most are gone now, collecting state pensions for their years of public service, having long since washed their hands of all that ever happened in prison.

Behold the Man!

I don’t tell this story because I equate myself with Christ. It’s just the opposite. In each Holy Week post I’ve written, I find that I am some other character in this scene. I’ve been “Simon of Cyrene, Compelled to Carry the Cross.” I’ve been “Dismas, Crucified to the Right.” I tell this story first because it’s the truth, and second because having lived it, I today look upon that scene of Christ before Pilate on my wall, and I see it differently than most of you might. I relate to it perhaps a bit more than I would had I myself never stood before Pilate.

Having stared for three years at this scene fixed upon my cell wall, words cannot describe the sheer force of awe and irony I felt when someone sent me an October 2013 article by Carlos Caso-Rosendi written and published in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the home town of Pope Francis. The article was entitled, “Behold the Man!” and it was about my trial and imprisonment. Having no idea whatsoever of the images upon my cell wall, Carlos Caso-Rosendi’s article began with this very same image: Antonio Ciseri’s 1871 painting, “Ecce Homo!” TSW reader, Bea Pires, printed Carlos’ article and sent it to Pope Francis.

I read the above paragraphs to Pornchai-Maximilian about the power of this scene on my wall. He agrees that he, too, finds this image over on my side of this cell to be vaguely troubling and disconcerting, and for the same reasons I do. He has also lived the humiliation the scene depicts, and because of that he relates to the scene as I do, with both reverence and revulsion. “That’s why it stay on your wall,” he said, “and never found its way over to mine!”

Aha! A confession!

+ + +

Note from the Editor: Please visit our Holy Week Posts Page.

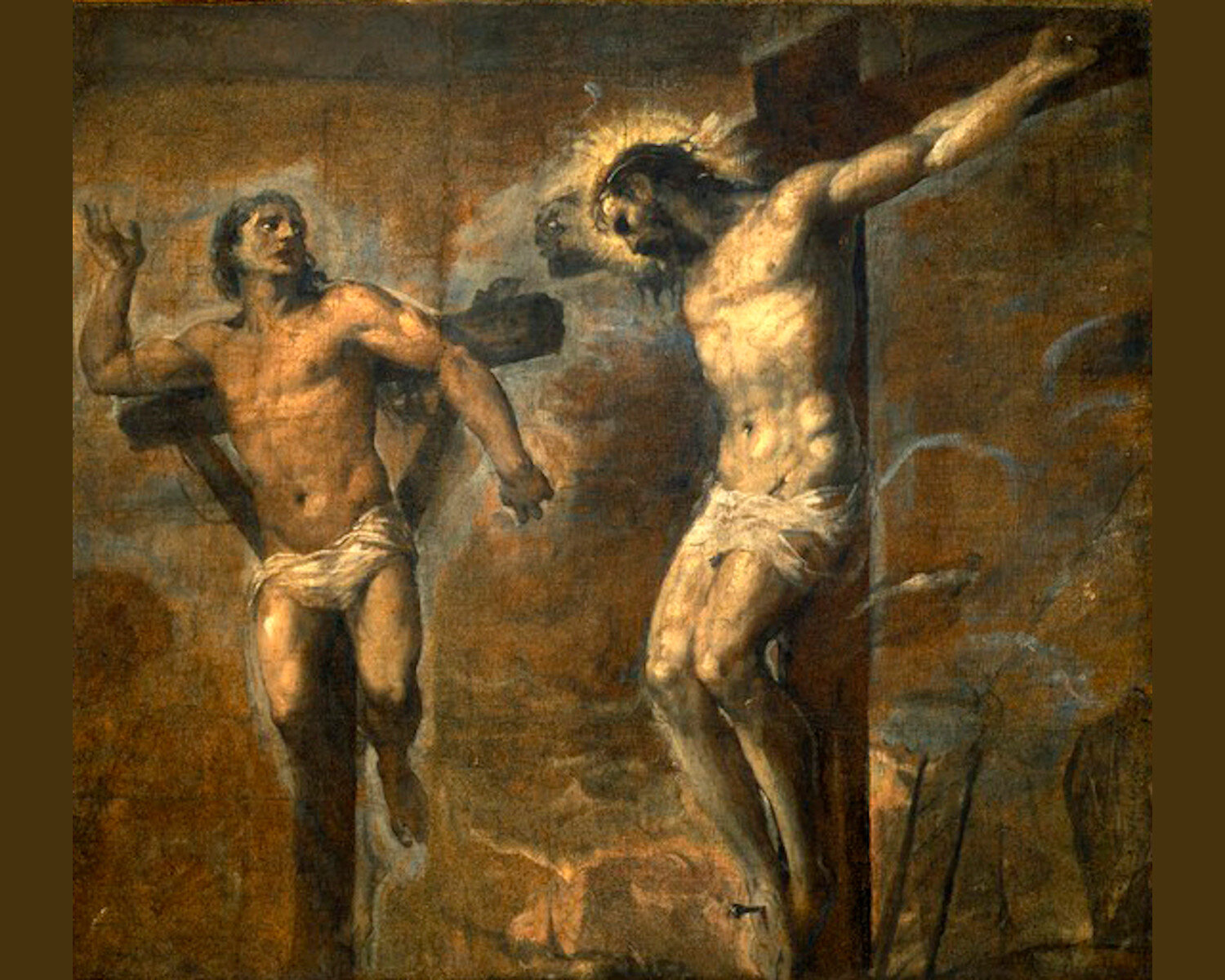

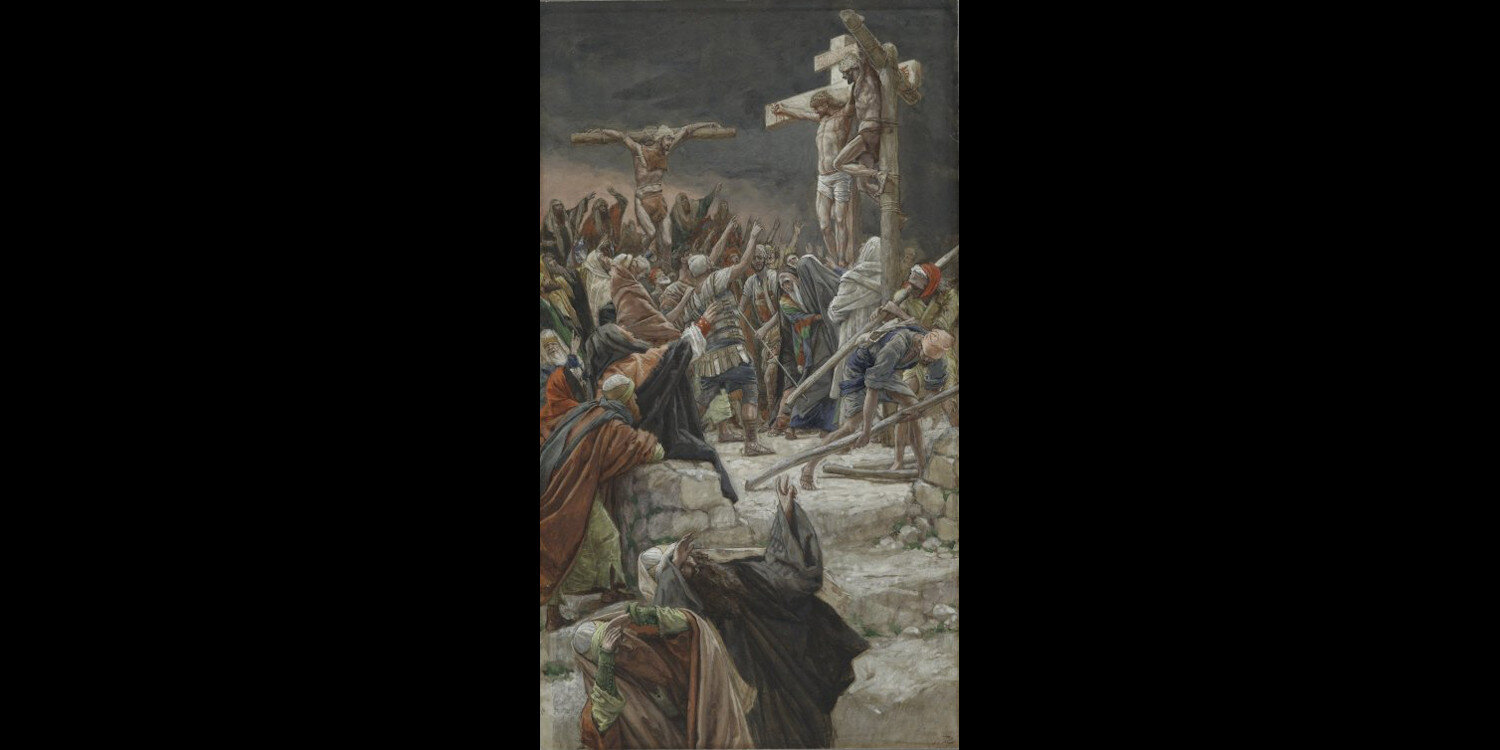

Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found

Who was Saint Dismas, the Penitent Thief, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Christians.

Who was Saint Dismas, the penitent criminal, crucified to the right of Jesus at Calvary? His brief Passion Narrative appearance has deep meaning for Salvation.

“All who see me scoff at me. They mock me with parted lips; they wag their heads.”

During Holy Week one year, I wrote “Simon of Cyrene, the Scandal of the Cross, and Some Life Sight News.” It was about the man recruited by Roman soldiers to help carry the Cross of Christ. I have always been fascinated by Simon of Cyrene, but truth be told, I have no doubt that I would react with his same spontaneous revulsion if fate had me walking in his sandals that day past Mount Calvary.

Some BTSW readers might wish for a different version, but I cannot write that I would have heroically thrust the Cross of Christ upon my own back. Please rid yourselves of any such delusion. Like most of you, I have had to be dragged kicking and screaming into just about every grace I have ever endured. The only hero at Calvary was Christ. The only person worth following up that hill — up ANY hill — is Christ. I follow Him with the same burdens and trepidation and thorns in my side as you do. So don’t follow me. Follow Him.

This Holy Week, one of many behind these stone walls, has caused me to use a wider angle lens as I examine the events of that day on Mount Calvary as the Evangelists described them. This year, it is Dismas who stands out. Dismas is the name tradition gives to the man crucified to the right of the Lord, and upon whom is bestowed a dubious title: the “Good Thief.”

As I pondered the plight of Dismas at Calvary, my mind rolled some old footage, an instant replay of the day I was sent to prison — the day I felt the least priestly of all the days of my priesthood.

It was the mocking that was the worst. Upon my arrival at prison after trial late in 1994, I was fingerprinted, photographed, stripped naked, showered, and unceremoniously deloused. I didn’t bother worrying about what the food might be like, or whether I could ever sleep in such a place. I was worried only about being mocked, but there was no escaping it. As I was led from place to place in chains and restraints, my few belongings and bedding stuffed into a plastic trash bag dragged along behind me, I was greeted by a foot-stomping chant of prisoners prepped for my arrival: “Kill the priest! Kill the priest! Kill the priest!” It went on into the night. It was maddening.

It’s odd that I also remember being conscious, on that first day, of the plight of the two prisoners who had the misfortune of being sentenced on the same day I was. They are long gone now, sentenced back then to just a few years in prison. But I remember the walk from the courthouse in Keene, New Hampshire to a prison-bound van, being led in chains and restraints on the “perp-walk” past rolling news cameras. A microphone was shoved in my face: “Did you do it, Father? Are you guilty?”

You may have even witnessed some of that scene as the news footage was recently hauled out of mothballs for a WMUR-TV news clip about my new appeal. Quickly led toward the van back then, I tripped on the first step and started to fall, but the strong hands of two guards on my chains dragged me to my feet again. I climbed into the van, into an empty middle seat, and felt a pang of sorrow for the other two convicted criminals — one in the seat in front of me, and the other behind.

“Just my %¢$#@*& luck!” the one in front scowled as the cameras snapped a few shots through the van windows. I heard a groan from the one behind as he realized he might vicariously make the evening news. “No talking!” barked a guard as the van rolled off for the 90 minute ride to prison. I never saw those two men again, but as we were led through the prison door, the one behind me muttered something barely audible: “Be strong, Father.”

Revolutionary Outlaws

It was the last gesture of consolation I would hear for a long, long time. It was the last time I heard my priesthood referred to with anything but contempt for years to come. Still, to this very day, it is not Christ with whom I identify at Calvary, but Simon of Cyrene. As I wrote in “Simon of Cyrene and the Scandal of the Cross“:

“That man, Simon, is me . . . I have tried to be an Alter Christus, as priesthood requires, but on our shared road to Calvary, I relate far more to Simon of Cyrene. I pick up my own crosses reluctantly, with resentment at first, and I have to walk behind Christ for a long, long time before anything in me compels me to carry willingly what fate has saddled me with . . . I long ago had to settle for emulating Simon of Cyrene, compelled to bear the Cross in Christ’s shadow.”

So though we never hear from Simon of Cyrene again once his deed is done, I’m going to imagine that he remained there. He must have, really. How could he have willingly left? I’m going to imagine that he remained there and heard the exchange between Christ and the criminals crucified to His left and His right, and took comfort in what he heard. I heard Dismas in the young man who whispered “Be strong, Father.” But I heard him with the ears of Simon of Cyrene.

Like a Thief in the Night

Like the Magi I wrote of in “Upon a Midnight Not So Clear,” the name tradition gives to the Penitent Thief appears nowhere in Sacred Scripture. Dismas is named in a Fourth Century apocryphal manuscript called the “Acts of Pilate.” The text is similar to, and likely borrowed from, Saint Luke’s Gospel:

“And one of the robbers who were hanged, by name Gestas, said to him: ‘If you are the Christ, free yourself and us.’ And Dismas rebuked him, saying: ‘Do you not even fear God, who is in this condemnation? For we justly and deservedly received these things we endure, but he has done no evil.’”