“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Of Saints and Souls and Earthly Woes

For Catholics, the month of November honors our beloved dead, and is a time to reenforce our civil liberties especially the one most endangered: Religious Freedom.

For Catholics, the month of November honors our beloved dead, and is a time to reinforce our civil liberties especially the one most endangered: Religious Freedom.

November 2, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

A lot of attention has been paid to a recent post by Pornchai Moontri. Writing in my stead from Thailand, his post was “Elephants and Men and Tragedy in Thailand.” Many readers were able to put a terrible tragedy into spiritual perspective. Writer Dorothy R. Stein commented on it: “The Kingdom of Thailand weeps for its children. Only a wounded healer like Mr. Pornchai Moontri could tell such a devastating story and yet leave readers feeling inspired and hopeful. This is indeed a gift. I have read many accounts of this tragedy, but none told with such elegant grace.”

A few years ago I wrote of the sting of death, and the story of how one particular friend’s tragic death stung very deeply. But there is far more to the death of loved ones than its sting. A decade ago at this time I wrote a post that helped some readers explore a dimension of death they had not considered. It focused not only on the sense of loss that accompanies the deaths of those we love, but also on the link we still share with them. It gave meaning to that “Holy Longing” that extends beyond death — for them and for us — and suggested a way to live in a continuity of relationship with those who have died. The All Souls Day Commemoration in the Roman Missal also describes this relationship:

“The Church, after celebrating the Feast of All Saints, prays for all who in the purifying suffering of purgatory await the day when they will join in their company. The celebration of the Mass, which re-enacts the sacrifice of Calvary, has always been the principal means by which the Church fulfills the great commandment of charity toward the dead. Even after death, our relationship with our beloved dead is not broken.”

That waiting, and our sometimes excruciatingly painful experience of loss, is “The Holy Longing.” The people we have loved and lost are not really lost. They are still our family, our friends, and our fellow travelers, and we shouldn’t travel with them in silence. The month of November is a time to restore our spiritual connection with departed loved ones. If you know others who have suffered the deaths of family and friends, please share with them a link to “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.”

The Communion of Saints

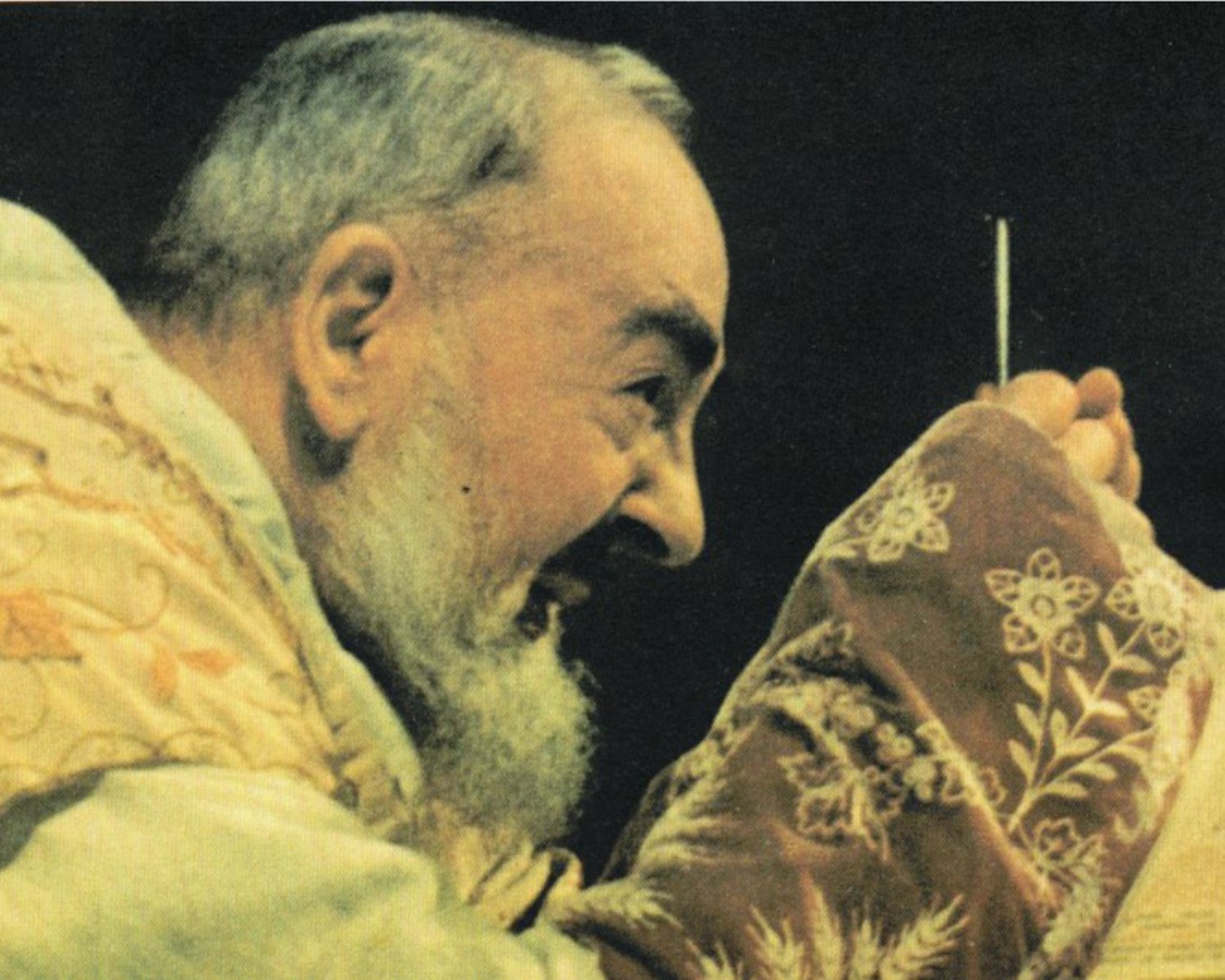

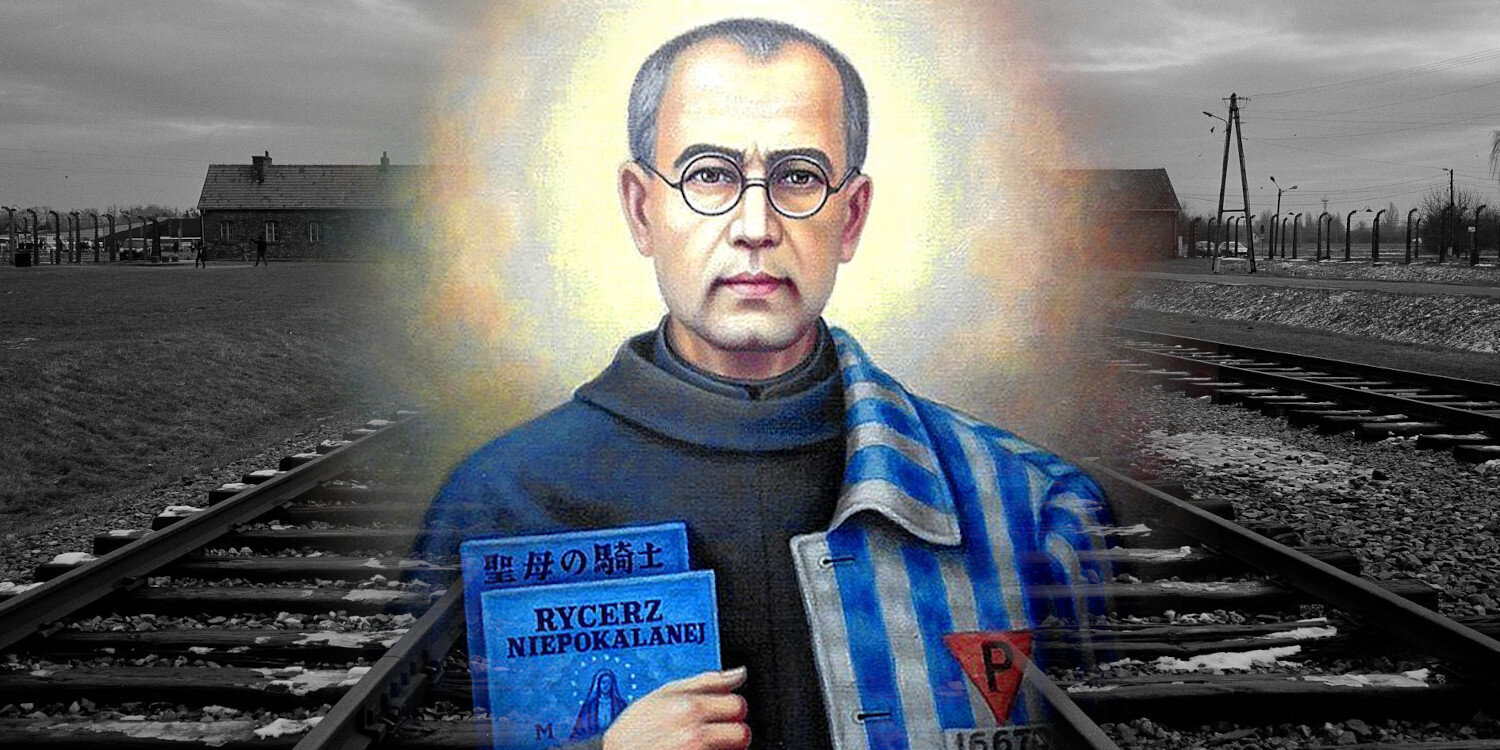

I’ve written many times about the saints who inspire us on this arduous path. The posts that come most immediately to mind are “A Tale of Two Priests: Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul II,” and more recently, “With Padre Pio When the Worst that Could Happen Happens.” Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Saint Padre Pio inspire me not because I have so much in common with them, but because I have so little. I am not at all like them, but I came to know them because I was drawn to the ways they faced and coped with adversity in their lives on Earth.

Patron saints really are advocates in Heaven, but the story is bigger than that. To have patron saints means something deeper than just hoping to share in the graces for which they suffered. It means to be in a relationship with them as role models for our inevitable encounter with human trials and suffering. They can advocate not only for us, but for the souls of those we entrust to their intercession. In the Presence of God, they are more like a lens for us, and not dispensers of grace in their own right. The Protestant critique that Catholics “pray to saints” has it all wrong.

To be in a relationship with patron saints means much more than just waiting for their help in times of need. I have learned a few humbling things this year about the dynamics of a relationship with Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio. I have tried to consciously cope with painful things the way they did, and over time they opened my eyes about what it means to have their advocacy. It’s an advocacy I would not need if I were even remotely like them. It’s an advocacy I need very much, and can no longer live without.

I don’t think we choose the saints who will be our patrons and advocates in Heaven. I think they choose us. In ways both subtle and profound, they interject their presence in our lives. I came into my unjust imprisonment over 28 years ago knowing little to nothing of Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio. But in multiple posts at Beyond These Stone Walls I’ve written of how they made their presence here known. And in that process, I’ve learned a lot about why they’re now in my life. It is not because they look upon me and see their own paths. It’s because they look upon me and see how much and how easily I stray from their paths.

I recently discovered something about the intervention of these saints that is at the same time humbling and deeply consoling. It’s consoling because it affirms for me that these modern saints have made themselves a part of what I must bear each day. It’s humbling because that fact requires shedding all my notions that their intercession means a rescue from the crosses I’d just as soon not carry.

Over the last few years, I’ve had to live with something that’s very painful — physically very painful — and sometimes so intensely so that I could focus on little else. In prison, there are not many ways to escape from pain. I can purchase some over-the-counter ibuprophen in the prison commissary, but that’s sort of like fighting a raging forest fire with bottled water. It’s not very effective. At times, the relentless pain flared up and got the better of me, and I became depressed. There aren’t many ways to escape depression in prison either. The combination of nagging pain and depression began to interfere with everything I was doing, and others started to notice. The daily barrage of foul language and constantly loud prison noise that I’ve heard non-stop for over 28 years suddenly had the effect of a rough rasp being dragged across the surface of my brain. Many of you know exactly what I mean.

So one night, I asked Saint Padre Pio to intercede that I might be delivered from this awful nagging pain. I fell off to sleep actually feeling a little hopeful, but it was not to be. The next morning I awoke to discover my cross of pain even heavier than the night before. Then suddenly I became aware that I had just asked Padre Pio — a soul who in life bore the penetrating pain of the wounds of Christ without relief for fifty years — to nudge the Lord to free me from my pain. What was I thinking?! That awareness was a spiritually more humbling moment than any physical pain I have ever had to bear.

So for now, at least, I’ll have to live with this pain, but I’m no longer depressed about it. Situational depression, I have learned, comes when you expect an outcome other than the one you have. I no longer expect Padre Pio to rescue me from my pain, so I’m no longer depressed. I now see that my relationship with him isn’t going to be based upon being pain free. It’s going to be what it was initially, and what I had allowed to lapse. It’s the example of how he coped with suffering by turning himself over to grace, and by making an offering of what he suffered.

A rescue would sure be nice, but his example is, in the long run, a lot more effective. I know myself. If I awake tomorrow and this pain is gone forever, I will thank Saint Padre Pio. Then just as soon as my next cross comes my way — as I once described in “A Shower of Roses” — I will begin to doubt that the saint had anything to do with my release.

His example, on the other hand, is something I can learn from, and emulate. The truth is that few, if any, of the saints we revere were themselves rescued from what they suffered and endured in this life. We do not seek their intercession because they were rescued. We seek their intercession because they bore all for Christ. They bore their own suffering as though it were a shield of honor and they are going to show us how we can bear our own.

For Greater Glory

Back in 2010 when my friend Pornchai Moontri was preparing to be received into the Church, he asked one of his “upside down” questions. I called them “upside down” questions because as I lay in the bunk in our prison cell reading late at night, his head would pop down from the upper bunk so he appeared upside down to me as he asked a question. “When people pray to saints do they really expect a miracle?” I asked for an example, and he said, “Should you or I ask Saint Maximilian Kolbe for a happy ending when he didn’t have one himself?”

I wonder if Pornchai knew how incredibly irritating it was when he stumbled spontaneously upon a spiritual truth that I had spent months working out in my own soul. Pornchai’s insight was true, but an inconvenient truth — inconvenient by Earthly hopes, anyway. The truth about Auschwitz, and even a very long prison sentence, was that all hope for rescue was the first hope to die among any of its occupants. As Maximilian Kolbe lay in that Auschwitz bunker chained to, but outliving, his fellow prisoners being slowly starved to death, did he expect to be rescued?

All available evidence says otherwise. Father Maximilian Kolbe led his fellow sufferers into and through a death that robbed their Nazi persecutors of the power and meaning they intended for that obscene gesture. How ironic would it be for me to now place my hope for rescue from an unjust and uncomfortable imprisonment at the feet of Saint Maximilian Kolbe? Just having such an expectation is more humiliating than prison itself. Devotion to Saint Maximilian Kolbe helped us face prison bravely. It does not deliver us from prison walls, but rather from their power to stifle our souls.

I know exactly what brought about Pornchai’s question. Each weekend when there were no programs and few activities in prison, DVD films were broadcast on a closed circuit in-house television channel. Thanks to a reader, a DVD of the soul-stirring film, “For Greater Glory” was donated to the prison. That evening we were able to watch the great film. It was an hour or two after viewing this film that Pornchai asked his “upside-down” question.

“For Greater Glory” is one of the most stunning and compelling films of recent decades. You must not miss it. It’s the historically accurate story of the Cristero War in Mexico in 1926. Academy Award nominee Andy Garcia portrays General Enrique Gorostieta Delarde in a riveting performance as the leader of Mexico’s citizen rebellion against the efforts of a socialist regime to diminish and then eradicate religious liberty and public expressions of Christianity, especially Catholic faith.

If you haven’t seen “For Greater Glory,” I urge you to do so. Its message is especially important before drawing any conclusions about the importance of the issue of religious liberty now facing Americans and all of Western Culture. As readers in the United States know well, in a matter of days we face a most important election for the future direction of Congress and the Senate.

“For Greater Glory” is an entirely true account, and portrays well the slippery slope from a government that tramples upon religious freedom to the actual persecution, suppression and cancelation of priests and expressions of Catholic faith and witness. If you think it couldn’t happen here, think again. It couldn’t happen in Mexico either, but it did. We may not see our priests publicly executed, but we are already seeing them in prison without just cause, and even silenced by their own bishops, sometimes just for boldly speaking the truth of the Gospel. You have seen the practice of your faith diminished as “non-essential” by government dictate during a pandemic.

The real star of this film — and I warn you, it will break your heart — is the heroic soul of young José Luis Sánchez del Río, a teen whose commitment to Christ and his faith results in horrible torment and torture. If this film were solely the creation of Hollywood, there would have been a happy ending. José would have been rescued to live happily ever after. It isn’t Hollywood, however; it’s real. José’s final tortured scream of “Viva Cristo Rey!” is something I will remember forever.

I cried, finally, at the end as I read in the film’s postscript that José Luis Sánchez del Río was beatified as a martyr by Pope Benedict XVI after his elevation to the papacy in 2005. Saint José was canonized October 16, 2016 by Pope Francis, a new Patron Saint of Religious Liberty. His Feast Day is February 10. José’s final “Viva Cristo Rey!” echoes across the century, across all of North America, across the globe, to empower a quest for freedom that can be found only where young José found it.

“Viva Cristo Rey!”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Our Faith is a matter of life and death, and it diminishes to our spiritual peril. Please share this post. You may also like these related posts to honor our beloved dead in the month of November.

Elephants and Men and Tragedy in Thailand

The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts

The God of the Living and the Life of the Dead

A Not-so-Subtle Wake-Up Call from Christ the King

To assist your friends from Beyond These Stone Walls, please visit our Special Events page.

With Padre Pio When the Worst That Could Happen Happens

Inspired by Padre Pio's surrender to sacrificial suffering, this priest wrongly imprisoned for 28 years still sees signs and wonders even in life's darkest days.

Inspired by Padre Pio’s surrender to sacrificial suffering, this priest wrongly imprisoned for 29 years still sees signs and wonders even in life’s darkest corners.

September 21, 2022 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

I write this week in honor of Saint Pio of Pietrelcina, more popularly known as Padre Pio. He is one of the two Patron Saints of Beyond These Stone Walls and one who has had a living presence in my life behind these walls. The other, of course, is Saint Maximilian Kolbe. Pornchai Moontri and I share a somewhat mystical connection with both. A little time spent at “Our Patron Saints” in the BTSW Public Library might demonstrate how they have come to our spiritual aid in the darkest times of our lives here.

Though they were 20th Century contemporaries, Padre Pio and Maximilian Kolbe did not know each other except by reputation. Among the many letters of Padre Pio to pilgrims who wrote to him are several in which he urged suffering souls to enroll in the Militia of the Immaculata and Knights at the Foot of the Cross, the two spiritual movements founded by Maximilian Kolbe. I stumbled upon this after Pornchai Moontri and I enrolled in both. It is ironic that both saints were canonized by another saint. The lives of St. Padre Pio, St. Maximilian and St. John Paul II were lived with heroic virtue even as they suffered. I wrote of the latter two in a recent post that touched the hearts of many: “A Tale of Two Priests: Maximilian Kolbe and John Paul II.”

Padre Pio also had a global reputation for doing remarkable things, but he did them in the midst of remarkable suffering. After bearing the wounds of Christ for a half century he passed from this life on September 23, 1968, the date upon which the Church now honors him. On that same date, 26 years later, I was wrongly convicted and sent to prison for life after having tossed aside three chances to save myself and my freedom with a lie.

Since that day, September 23, 1994, Padre Pio has injected himself into my life in profoundly grace-filled ways. I have written of these encounters in multiple posts, but the two that seem to stand out the most are “Padre Pio: Witness for the Defense of Wounded Souls” and one that delves into the deeper mysteries of his life and death, “I Am a Mystery to Myself! The Last Days of Padre Pio.” We will link to them again at the end of this post and invite you to read them in his honor this week.

Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane

As long as our lives are tied to this world, we will never resolve the mystery of suffering. Like so many of you, I, too, have been confronted with the paradox of suffering. We are trapped in it because, unlike God, we live a linear existence. We see only what has come before and what is now, but we can only imagine what is to come.

But God lives in the '“nunc stans,” the “eternal now” seeing all at once our past, present, and future. Some believers expect God to be the Director of the play that is our lives, but He is more a participant than a director. He allows suffering as a means toward a specific end, but the end is His and not necessarily ours. In my post, “Waking Up in the Garden of Gethsemane,” Jesus discovers that the very first of his suffering is that he is inflicted with a human heart. He asks God to take away the great suffering that is to come, “but Thy will be done.” It is an aspect of the truth of the Resurrection that Jesus brought both His Divinity and the human heart with him when He opened the Kingdom of Heaven to us.

I have encountered this same paradox about suffering, and did so again on the night before writing this post. It comes in the night as a nagging litany of “What-Ifs.” It consists of a series of inflection points, points at which, in my own history, my current state in life could have been avoided had I turned left instead of right. I have identified about five such times and places in my life when a different decision would likely have prevented all the unseen suffering that was to follow.

But “What-Ifs” are spiritually unproductive. They deny the sacrificial nature of at least some of what we suffer and they disregard the plan God has for our souls. During my most recent nighttime Litany of “What-Ifs,” I was reminded of that prayer by St. John Henry Newman that I wrote about in “Divine Mercy in a Time of Spiritual Warfare”:

“God has created me to do Him some definite service. He has committed some work to me which he has not committed to another. I have my mission. I may never know it in this life, but I shall be told it in the next …”

I do not have the gift of foresight, but my hindsight is clear. Had I allowed myself to take any of those five alternate steps that I have been reminiscing about, then the work committed to me and no other could not have taken place, and a life and soul may have been lost forever. That life and soul became important to me, but only because it was a work God committed to me and no one else. It was the life and soul of my friend, Pornchai whom God has clearly called out of darkness. It is my great honor to have been an instrument of the immense grace that transformed Pornchai, but to be such an instrument means never to ask,”What was in it for me?”

So, if given the chance now, would I trade Pornchai’s life, freedom, and soul to erase the last 28 years of my own unjust imprisonment and vilification? Our Lord answered that question with one of his own: “What father among you would give his son a stone if he asks for bread?” (Matthew 7:10). This verse is followed just a few verses further by one that I wrote about recently in “To the Kingdom of Heaven Through a Narrow Gate”:

“Enter through the narrow gate, for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it.”

— Matthew 7:13-14

I could not have foreseen any meaning in what I suffered during my own agony in the garden. Such clarity is only in hindsight. Being sent to prison on false charges seemed to me the worst thing that could ever happen to a person — certainly the worst that could ever happen to a priest because a priest in such a circumstance is almost equally reviled by both Church and State. But today, when recognition of the alternative dawned — recognition that the life and soul of my friend would have been lost forever — I find that I can bear this suffering. I do not choose it. It chose me.

When Padre Pio Stepped In

The story of how Padre Pio stepped into my life as a priest and prisoner came also through Pornchai Moontri. Like Padre Pio himself, I had been shunned and vilified by Catholic activists in groups like S.N.A.P. and V.O.T.F. Out of fear, many other priests and Church officials joined in that shunning during my first decade in prison. The police, the courts, the news media, and the rumor mill in my diocese all amounted to a perfect storm that I was powerless to overcome. In 2002, the storm became a hurricane, first in Boston, then in New Hampshire and from there across the country.

In 2005, The Wall Street Journal’s explosive 2-part publication of “A Priest’s Story” altered the landscape. After it was published, Catholic League President Bill Donohue reached out to me with an invitation to write an article for the Catholic League Journal, Catalyst. My article, “Sex Abuse and Signs of Fraud” was published in the November 2005 issue.

When I received that month’s issue, I was more stricken by its front-page revelation than with my own centerpiece article. It was “Padre Pio Defamed.” I was shocked to learn, for the first time, that Padre Pio suffered more than the visible wounds of the crucified Christ. He also suffered a cascade of slander from both secular and church officials with wild suspicions and accusations that he sexually abused women in the confessional resulting in multiple Church investigations. In 1952, the Congregation of the Holy Office placed in its Index of Forbidden Books all books about Padre Pio.

Heaven can be most forgiving. The bishop who suspended the priestly faculties of Padre Pio based on the rapid spread of false information was Bishop Albino Luciani. Just a few weeks ago after a miracle attributed to his intercession was confirmed, he was beatified as Blessed Pope John Paul I.

It is ironic — not to mention boldly courageous — that Pope John Paul II canonized Padre Pio in 2002 at the height of media vitriol during the clergy abuse scandal in the United States. One of the last investigations against Padre Pio was a 1960 report lodged by Father Carlo Maccari alleging, with no evidence, that Padre Pio had sexual liaisons with female penitents twice per week.

In the same month my Catalyst article was published, Tylor Cabot joined the slander in the November 2005 issue of Atlantic Monthly with “The Rocky Road to Sainthood.” He wrote, “despite questions raised by two papal emissaries — and despite reported evidence that [Padre Pio] raised money for right-wing religious groups and had sex with penitents — Pio was canonized in 2002.”

Fr. Maccari’s original slander also found its way into The New York Times. Maccari went on to become an archbishop. On his deathbed, Maccari recanted his story as a monstrous lie born of jealousy. He prayed on his deathbed for the intercession of Padre Pio, the victim of his slander.

A Heaven-Sent Blessing from Padre Pio

Also in November of 2005, Pornchai Moontri arrived in this prison after his experience of all the events I described in “Getting Away with Murder on the Island of Guam.” Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio teamed up to reverse in him a road to destruction in ways that I was powerless to even imagine. A few years later, in 2009, this blog was born and some of my earliest posts were about what Padre Pio and Maximilian Kolbe suffered in life on the road to becoming the spiritual advocates they have been for us and millions of others. Just after I wrote about Padre Pio for the first time, I received a letter from Pierre Matthews from Ostend, Belgium who had been writing to me since reading of me in The Wall Street Journal.

Learning of my faith despite false charges and imprisonment became for Pierre the occasion for his return to faith and the Church after a long European lapse. When he read my early posts about the plight of Padre Pio, Pierre excitedly told me of a mystical encounter he had with Padre Pio as a young man. A letter from his father to him at his boarding school in Italy instructed him to go to San Giovanni Rotondo to ask for the blessing of the famous stigmatist, Padre Pio.

When 16-year-old Pierre got there, a friar answering the door told him this was impossible. He then gave Pierre a blessed holy card and ushered him toward the door. Just then, while inside the cavernous Capuchin Friary, an old man with bandaged hands came slowly down a flight of stairs and walked directly to the surprised teenager. Padre Pio held Pierre there firmly with his bandaged hands while he spoke aloud a blessing and prayer. Pierre was stunned, and never forgot it.

Sixty years later, Pierre had a dream that this blessing from Padre Pio was for us, and he wanted to pass it on. He insisted that he must be permitted to become Pornchai Moontri’s Godfather when Pornchai was received into the Church on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010.

Pierre left this life in 2020 just as Pornchai was awaiting his deportation to Thailand, his emergence from prison and the start of a new life. To this day, we both hold Padre Pio in awe as a mentor and friend. He gave us spiritual hope when there was none in sight. His advice is profoundly simple and characteristically blunt:

“Pray, hope, and don’t worry.”

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading. Please share this post so it may come before someone who needs it. And please Subscribe if you have not done so already. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls.

I Am a Mystery to Myself! The Last Days of Padre Pio

Stones for Pope Benedict and the Rusty Wheels of Justice

Following revelations about possible deliverance after 28 years of wrongful imprisonment, hope is hard to come by, but it was not so for Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

Following revelations about possible deliverance after 28 years of wrongful imprisonment, hope is hard to come by, but it was not so for Saint Maximilian Kolbe.

February 9, 2022

“This prisoner of the State remains, against all probability, staunch in spirit, strong in the faith that the wheels of justice turn, however slowly.”

— Dorothy Rabinowitz, “The Trials of Father MacRae,” The Wall Street Journal, May 13, 2013

When this blog was but a year old back in 2010, my friend and prison roommate, Pornchai Moontri, was received into the Catholic faith. He was 36 years old and it was his 18th year in prison. Everyone who knew him, except me, thought his conversion seemed quite impossible. Pornchai does not have an evil bone in his body, but his traumatic life had a profound effect on his outlook on life and his capacity for hope. There is simply no point in embracing faith without cultivating hope. The two go hand in hand. We cannot have one without the other.

To sow the seeds of hope in Pornchai, I had to first reawaken hope from its long dormant state in my own life as a prisoner. I am not entirely sure that I have completed that task. It seems a work in progress, but Pornchai’s last words to me as he walked through the prison gates toward freedom on September 8, 2020 were, “Thank you for giving me hope.” I wrote of that day in “Padre Pio Witness for the Defense of Wounded Souls.”

A decade earlier, back in April of 2010, Pornchai entered into Communion with the Catholic Church on Divine Mercy Sunday. On the night before, he asked me a haunting question. It was what I call one of his “upside down” questions. As he pondered what was to come, his head popped down from his upper bunk so he appeared upside down as he asked it. “Is it okay for us to hope for a happy ending when Saint Maximilian didn’t have one?” Pornchai had a knack for knocking me off the rails with questions like that.

Before responding, I had to do some pondering of my own. Our Patron Saint lost his earthly life at age 41 in a Nazi concentration camp starvation bunker. His death was followed by his rapid incineration. All that Maximilian Kolbe was in his earthly existence went up in smoke and ash to drift in the skies above Auschwitz, the most hopeless place in modern human history.

Retroactive Guilt and Shame

What I am about to write may seem horribly unpopular with those harboring an agenda against Catholic priests, but popularity has never been an important goal for me. In recent weeks, the news media has trumpeted a charge launched by a commission empowered by some Catholic officials in Germany. The commission’s much-hyped conclusion was that Pope Benedict was negligent when he did not remove four priests quickly enough after suspicions of abuse forty-one years ago in 1981. Some of my friends have cautioned me to stay out of this. Perhaps I should listen.

But I won’t. At what point do we cease judging men of the past for not living up to the ideals and politically correct sensitivities of the present? Merely asking that question puts me in the crosshairs of our victim culture, but it also forces me to ask another. Go back just another forty-one years and you will find yourself amid the hopelessness of 1941 as the children of Yahweh suffered unspeakable crimes in Germany and Poland. Where do we draw the line of historic condemnation? Should the German Church stop with Joseph Ratzinger in 1981?

The condemnation of Pope Benedict called for by some media and German officials today should be seen through the lens of history. It is a part of our hope as Catholics and as human beings that neither Pope Benedict nor the German people would act today as they did — or allowed to be done — forty or eighty years ago. The real target of such pointless inquiry and blame was not Pope Benedict, but rather hope itself.

I think we have to be clear in our response which should include something about the splinters in our eyes and the planks in the eyes of those pointing misplaced fingers of blame. Perhaps the moral authority that chastises Pope Benedict today in Germany doth protesteth too much. A new book by historian Harald Jähner, Aftermath: Life in the Fallout of the Third Reich, 1945-1955 marshals a plethora of facts and critical skills of historical writing to portray the postwar “country’s stubborn inclination toward willful delusion.”

Thank you for indulging my brief tirade. Catholic League President Bill Donohue also came to the defense of Pope Benedict by shedding some light of historical context on the matter.

Hope Is Its Own Fulfillment

But back to Father Maximilian Kolbe. On the day of Pornchai’s Baptism, I responded to his question. I told him, “YOU are Maximilian’s happy ending!” Eighty-one years after his martyrdom at Auschwitz, the world honors him while the names of those who destroyed him have simply faded into oblivion. No one honors them. No one remembers them. God remembers. Their footprint on the Earth left only sorrow.

St. Maximilian Kolbe is the reason why I was compelled to set aside my own quest for freedom — which seemed utterly hopeless the last time I looked — in order to do what Maximilian did: to save another.

In all the anguish of the last two years as deliverance and freedom slowly came to Pornchai Moontri, the clouds of the past that overshadowed him began to lift. My prayer had been constant, and of a consistently singular nature: “I ask for freedom for Pornchai; I ask for nothing for myself.”

I am no saint, but that is what St. Maximilian did, and it seemed to be my only path. But since then that 2013 quote atop this post from The Wall Street Journal's Dorothy Rabinowitz has once again become my reality. As you know if you have been reading these pages in recent weeks, a frenzy of action and high anxiety has surrounded the recent release of the New Hampshire ‘Laurie List,’ known more formally as the Exculpatory Evidence Schedule. If you somehow missed the earthquake that struck from Beyond These Stone Walls in January, I wrote about it in Predator Police: The New Hampshire ‘Laurie List’ Bombshell.

I am most grateful to readers for making the extra effort to share that post. It was emailed by Dr. Bill Donohue to the entire membership of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. It indeed came as a bombshell to me and to many. Just as the frenzy began to subside, Ryan MacDonald stirred it up again in his brilliant analysis with a very pointed title: “Police Misconduct: A Crusader Cop Destroys a Catholic Priest.”

I am not entirely sure that “destroys” is the right term to use, but I understand where he is coming from. To survive twenty-eight years of wrongful imprisonment means relegating a lot of one’s sense of self to the ash heap of someone else’s oppression. Many of those who spend decades in prison for crimes they did not commit lose their minds. Many also lose their faith, and along with it, all hope.

I have to remind myself multiple times a day that nothing is a sure thing anymore — neither prison nor freedom. I keep asking myself how much I dare to trust hope again. To quote the late Baseball Hall of Famer, Yogi Berra, this all feels “like deja vu all over again.”

Deja vu is a French term which literally means “to have seen before.” It is the strange sensation of having been somewhere before, or having previously experienced a current situation even though you know you have not. It is a phenomenon of neuropsychology that I have experienced all my life. About 15 percent of the population has that experience on occasion.

A possible explanation of deja vu is that aspects of the current situation act as retrieval cues in the psyche that unconsciously evoke an earlier experience long since receded from conscious memory, but resulting in an eerie sense of the familiar. It feels more strange than troublesome. I have a lifelong condition called Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE) which makes me prone to the experience of deja vu, but no one knows exactly why.

When Disappointments of the Past Haunt the Present

This time, my deja vu is connected to real events of the past, and the origin of my caution about current hope is found there. If you have read an important post of mine entitled “Grand Jury, St. Paul’s School, and the Diocese of Manchester,” then you may recall this story. In 2003 and 2004, the New Hampshire Attorney General conducted an intense one-sided investigation of my diocese, the Diocese of Manchester. When it was over, the former Bishop of Manchester signed a blanket release disposing of the privacy rights of priests of his diocese.

In 2021, when I wrote the above post, New Hampshire Judge Richard B. McNamara ruled that the 2003 public release of one-sided documents should have been barred under New Hampshire law because it was an abuse of the grand jury system and it denied basic rights of due process to those involved.

At the time this all happened in 2003, a Tennessee lawyer and law firm cited in a press statement that what happened in this diocese was unconstitutional. I contacted the lawyer who subsequently took a strong interest in my own case. He flew to New Hampshire twice to visit me in prison. I sent him a vast amount of documentation which he found most compelling. After many months of cultivated hope, he sent me a letter indicating that he would soon send a Memorandum of Understanding that I was to sign laying out the parameters under which he would represent me pro bono because I have not had an income for decades.

I waited. I waited a long time, but the Memorandum never came. Without explanation or communication of any kind, the lawyer and the hope he brought simply faded away. Letter after letter remained unanswered. It was inexplicable. It was at this same time that Dorothy Rabinowitz and The Wall Street Journal published a two-part exposé, A Priest’s Story, on the perversion of justice that became apparent in their independent review of this matter. Those articles were actually published a few years after they were first planned. This was because the reams of supporting documents requested and collected by the newspaper were destroyed in the collateral damage of the terrorist attacks in New York of September 11, 2001.

Then in 2012, new lawyers filed an extensive case for Habeas Corpus review of my trial and imprisonment. It is still available at the National Center for Reason and Justice which mercifully still advocates for justice for me. However that effort failed when both State and Federal judges declined to allow any hearing that would give new witnesses a chance to testify under oath.

Now, in 2022 in light of this new ray of hope, some of the people involved in Beyond These Stone Walls have expressed frustration with my caution and apparent pessimism. I have not been as enthused as they have been over the hope arising from the current situation. Hope for me has been like investing in the stock market. Having lost everything twice, I am hesitant to wade too far into the waters of hope again.

I know only too well, however, that hope at times such as these is like that which both Pornchai Moontri and I once found in our Patron Saint. I wrote about it in “Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance.”

So in spite of myself, I am now aboard this new train of hope and must go where it takes me. That, for now, is the best that I can do. My prayer has not changed. I ask for nothing for myself, but I will take whatever comes.

I thank you, as I have in the past, for your support and prayers and for being here with me again at this turning of the tide. I will keep you posted, but it won’t be quick. Real hope never is.

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae:

Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Please visit our newest addition to the BTSW menu: The Wall Street Journal. You may also wish to visit these relevant posts cited herein:

Predator Police: The New Hampshire ‘Laurie List’ Bombshell

Police Misconduct: A Crusader Cop Destroys a Catholic Priest

The Parable of a Priest and the Parable of a Prisoner

A Parable of Divine Mercy: Pornchai Moontri has a first birthday in freedom on September 10. One third of his life passed in a prison cell with a Catholic priest.

A Parable of Divine Mercy: Pornchai Moontri had a first birthday in freedom on September 10. One third of his life passed in a prison cell with a Catholic priest.

September 8, 2021

Jesus taught in parables, a word which comes from the Greek, paraballein, which means to “draw a comparison.” Jesus turned His most essential truths into simple but profound parables that could be easily pondered, remembered, and retold. The genre was not unique to Jesus. There are several parables that appear in our Old Testament. I wrote of one some time ago — though now I cannot recall which post it was — about the Prophet Jonah.

The Book of Jonah is one of a collection of twelve prophetic books known in the Hebrew Scriptures as the Minor Prophets. The Book of Jonah tells of events — some historical and some in parable form — in the life of an 8th-century BC prophet named Jonah. At the heart of the story, Jonah was commanded by God to go to Nineveh to convert the city from its wickedness. Nineveh was an ancient city on the Tigris River in what is now northern Iraq near the modern city of Mosul. It was the capital of the Assyrian Empire from 705-612 BC.

Jonah rebelled against the command of God and went in the opposite direction, boarding a ship to continue his flight from “the Presence of the Lord.” When a storm arose and the ship was imperiled, the mariners blamed Jonah and cast him into a raging sea. He was swallowed by “a great fish” (1:17), spent three days and nights in its belly, and then the Lord spoke to the fish and Jonah “was spewed out upon dry land” ( 2: 10) . ( I could add, as a possible aside, that the great fish might later have been sold at market, but there was no longer any prophet in it!)

Then God, undaunted by his rebellion, again commanded Jonah to go to Nineveh. Jonah finally went, did his best, the people repented, and God saved them from destruction. Many biblical scholars regard this part of the Book of Jonah as a parable. Jesus Himself referred to the Jonah story as a presage, a type of parable account pointing to His own death and Resurrection:

“Some of the scribes and Pharisees said to him, 'Teacher, we wish to see a sign from you.' But he answered them, 'An evil and adulterous generation asks for a sign, but no sign will be given except the sign of the Prophet Jonah. For just as Jonah was three days in the belly of the giant fish so for three days and three nights, the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth.”

— Matthew 12:38-40

What I take away from the parable part of the story of Jonah is that there is no point fleeing from “the Presence of the Lord.” God is not a puppeteer dangling and directing us from strings. Rather, the threads of our lives are intertwined with the threads of other lives in ways mysterious and profound. I have written several times of what I call “The Great Tapestry of God.” Within that tapestry — which in this life we see only from our place among its tangled threads — God connects people in salvific ways, and asks for our cooperation with these threads of connection.

The Parable of the Priest

I was slow to awaken to this. For too many days and nights in wrongful imprisonment, I pled my case to the Lord and asked Him to send someone to deliver me from this present darkness. It took a long time for me to see that perhaps I have been looking at this unjust imprisonment from the wrong perspective. I have railed against the fact that I am powerless to change it. I can only change myself. I know the meaning of the Cross of Christ, but I was spiritually blind to my own. Ironically, in popular writing, prison is sometimes referred to as “the belly of the beast.”

After a dozen years of railing against God in prison, I slowly came to the possible realization that no one was sent to help me because maybe I am the one being sent. My first nudge in this direction came upon reading one of the most mysterious passages in all of Sacred Scripture. It arose when I pondered what exactly happened to Jesus between the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, the three days He refers to in the Sign of Jonah parable in the Gospel of Matthew above. A cryptic hint is found in the First Letter of Peter:

“For it is better to suffer for good, if suffering should be God's will, than to suffer for evil. For Christ also suffered for sins once for all, the righteous for the unrighteous, in order to bring you to God. He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the Spirit, in which he also went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison who in former times did not obey.”

— 1 Peter 3:17-20

The second and much stronger hint also came to me in 2006, twelve years after my imprisonment commenced. This may be a familiar story to long time readers, but it is essential to this parable. I was visited in prison by a priest who learned of me from a California priest and canon lawyer whom I had never even met. The visiting priest was Father James McCurry, a Conventual Franciscan who, unknown to me at the time, had been a postulator for the cause of sainthood of St. Maximilian Kolbe whom I barely knew of.

Our visit was brief, but pivotal. Father McCurry asked me what I knew about Saint Maximilian Kolbe. I knew very little. A few days later, I received in the mail a letter from Father McCurry with a holy card (we could receive cards then, but not now). The card depicted Saint Maximilian in his Franciscan habit over which he partially wore the tattered jacket of an Auschwitz prisoner with the number, 16670. I was strangely captivated by the image and taped it to the battered mirror in my cell.

Later that same day, I realized with profound sadness that on the next day — December 23, 2006 — I would be a priest in prison one day longer than I had been a priest in freedom. At the edge of despair, I had the strangest sense that the man in the mirror, St. Maximilian, was there in that cell with me. I learned that he was canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1982, the year I was ordained. I spent a lot of time pondering what was in his heart and mind as he spontaneously stepped forward from a line of prisoners and asked permission to take the place of a weeping young man condemned to death by starvation. I wrote of the cell where he spent his last days in “Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance.”

On the very next day after pondering that man in the mirror on Christmas Eve, 2006 — a small but powerful book arrived for me. It was Man’s Search for Meaning, by Auschwitz survivor, Dr. Viktor Frankl, a Jewish medical doctor and psychiatrist who was the sole member of his family to survive the horror of the concentration camps. I devoured the little book several times. It was one of the most meaningful accounts of spiritual survival I had ever read. Its two basic premises were that we have one freedom that can never be taken from us: We have the freedom to choose the person we will be in any set of circumstances.

The other premise was that we will be broken by unending suffering unless we discover meaning in it. I was stunned to see at the end of this Jewish doctor’s book that he and many others attributed, in part, their survival of Auschwitz to Maximilian Kolbe “who selflessly deprived the camp commandant of his power over life and death.”

The Parable of a Prisoner

God did not will the evil through which Maximilian suffered and died, but he drew from it many threads of connection that wove their way into countless lives, and now I was among them. For Viktor Frankl, a Jewish doctor with an unusual familiarity with the Gospel, Maximilian epitomized the words of Jesus, “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

I asked the Lord to show me the meaning of what I had suffered. It was at this very point that Pornchai Moontri showed up in the Concord prison. I have written of our first meeting before, but it bears repeating. I was, by “chance,” late in the prison dining hall one evening. It was very crowded with no seats available as I wandered around with a tray. I was beckoned from across the room by J.J., a young Indonesian man whom I had helped with his looming deportation. “Hey G! Sit here with us. This is my new friend, Ponch. He just got here.”

Pornchai sat in near silence as J.J. and I spoke. I was shifting in my seat as Pornchai’s dagger eyes, and his distrust and rage were aimed in my direction. J.J. told him that I can be trusted. Pornchai clearly had extreme doubts.

Over the next month, Pornchai was moved in and out of heightened security because he was marked as a potential danger to others. Then one day as 2006 gave way to 2007, I saw him dragging a trash bag with his few possessions onto the cell block where I lived. He paused at my cell door and looked in. He stepped toward the battered mirror and saw the image of St. Maximilian Kolbe in his Franciscan habit and Auschwitz jacket and he stared for a time. “Is this you?” he asked.

Within a few months, Pornchai’s roommate moved away and I was asked to move in with him. Less than four years later, to make this long and winding parable short, Pornchai was received into the Catholic faith on Divine Mercy Sunday, 2010. Two years after that, on the Solemnity of Christ the King, 2012, we both followed Saint Maximilian Kolbe into Consecration to Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Most readers likely know by now the depth of the wounds Pornchai experienced in life. He was abandoned as a child in Thailand, suffered severe malnutrition, and then, at age eleven, he fell into the hands of a monster. He was taken from his country and the only family he knew, and was brought to the U.S. where he suffered years of unspeakable abuse. He escaped to a life of homelessness, living on the streets as a teenager in what was to him a foreign land. At age 18, he accidentally killed a much larger man during a struggle, and was sent to prison.

Pornchai’s mother, the only other person who knew of the years of abuse he suffered, was murdered on the Island of Guam after being taken there by the man who abused him. In 2018, after I wrote this entire account, that man, Richard Alan Bailey, was brought to justice and convicted of forty felony counts of sexual abuse of Pornchai. After the murder of his mother at that man’s hands, Pornchai gave up on life and spent the next seven years in the torment of solitary confinement in a supermax prison in the State of Maine. From there, he was moved here with me.

Over the ensuing years, as I gradually became aware of the enormity of Pornchai’s suffering, I felt compelled to act in the only manner available to me. I followed Saint Maximilian Kolbe into the Gospel passage that characterized his life in service to his fellow prisoners: “Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13)

I asked the Lord, through the Immaculate Heart of Mary, to free Pornchai from his past and the seemingly impenetrable prisons that held him bound. I offered the Lord my life and freedom just as Maximilian did on that August day of 1941. Then I witnessed the doors of Divine Mercy open to us.

This blog began just then. In the time he spent with me, Pornchai graduated from high school with honors, earned two additional diplomas in guidance and psychology, enrolled in theology courses at Catholic Distance University, and became an effective mentor for younger prisoners in a Fast Track program. He tutored young prisoners in mathematics as they pursued high school equivalency, and, as I have written above, he had a celebrated conversion to the Catholic faith, a story captured by Felix Carroll in his famous book, Loved, Lost, Found.

Pornchai became a master craftsman in woodworking, and taught his skill to other prisoners. One of his model ships is on display in a maritime museum in Belgium. His conversion story spread across the globe. After taking part in a number of Catholic retreat programs sponsored by Father Michael Gaitley and the Marians of the Immaculate Conception, Pornchai was honored as a Marian Missionary of Divine Mercy. So was I, but only because I was standing next to him.

One of the most beautiful pieces of writing that has graced this blog was not written by me, nor was it written for me. It was written for you. It was a post by Canadian writer Michael Brandon, a man I have never met, a man who silently followed the path of this parable for all these years. His presentation is brief, but unforgettable, and I will leave you with it. It is, “The Parable of the Prisoner.”

+ + +

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and the Gift of Noble Defiance

Book: Man’s Search for Meaning

Book: Loved, Lost, Found

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: On September 10, Pornchai will mark his 48th birthday. It is his first birthday in freedom. In 2020 on that date he was just beginning a grueling five months in ICE detention awaiting deportation. For the previous 29 years he was in prison. For the four years before that he was a homeless teenager having fled from a living nightmare.

I asked him what he would like for his birthday, and this was his response:

“I have never seen the ocean. I would like to go to the Gulf of Thailand and visit my cousin who was eight years old when I was eleven and last saw him. He is now an officer in the Thai Navy.”

Please visit our “SPECIAL EVENTS” page, and our BTSW Library category for posts about Pornchai.

A House Divided: Cancel Culture and the Latin Mass

In Traditionis Custodes restricting the Traditional Latin Mass, Pope Francis insists that his goal is ecclesial communion. Then he dropped a bombshell of division.

In Traditionis Custodes restricting the Traditional Latin Mass, Pope Francis insists that his goal is ecclesial communion. Then he dropped a bombshell of division.

In the above composite photo Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and Pope Francis offer Mass Ad Orientem in the Sistine Chapel.

August 11, 2021

The Year of Our Lord 2003 seemed a lot more like a year of Our Lord’s Calvary. It was a most painful year for me personally and for many Catholics. Starting in Boston with a rapid ripple effect across the land, diocese after diocese faced relentless Catholic scandal over the horror of Catholic priests accused of sexual abuse. A spotlight was cast upon the Catholic Church to the delight of the news media, but the subject needed a flood light. There was little justice in the moral panic to follow. This is a story I wrote about in a recent post, “A Sex Abuse Cover-Up in Boston Haunts the White House.”

Just beyond the glare of The Boston Globe spotlight, there was another event that had an even more profound impact on another church community in 2003. It took place just north of Boston in New Hampshire and from there it, too, rippled across the land, and many lands. Its most distinctive feature was its contrast to the Catholic story. While Catholic priests were judged and condemned in the media, one Episcopal clergyman in New Hampshire became a celebrity of pop culture.

In 2003, The Reverend V. Gene Robinson became the first openly gay Episcopalian priest to be nominated to become a bishop. The announcement had the immediate effect of alienating conservative members of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Born Vicky Gene Robinson in 1947, the nominee had been married, raised a family, divorced, and was in a conjugal same-sex relationship at the time of his nomination. For many, this seemed more of a politically correct statement than a serious nomination. If The Reverend Robinson had been divorced and living with another woman who was not his wife, this nomination would have gone nowhere.

Bishop Robinson’s nomination was confirmed by the Episcopal church of New Hampshire to equal parts applause and dismay. Then the cascade of damage was set in motion. With the support of the Nigerian Anglican church, many American conservative Episcopalians broke from the Worldwide Anglican Communion to form the Anglican Church in North America. The Anglican bishops of Uganda announced that they too broke from communion with the Episcopal church. This spread among conservative Anglican bishops across Africa and other parts of the world.

Having torn the Worldwide Anglican Communion asunder, Bishop Robinson announced his retirement seven years later in 2010. At some point he checked into drug rehab, and then used his voice as a retired bishop to promote same-sex marriage before the New Hampshire Legislature. He and his partner were among the first to “marry” under the new law he helped to pass. Then he announced his divorce to a news media that kept it very low key.

Among the protests came a multitude of petitions to Pope Benedict XVI who, in 2009, promulgated the Motu Proprio, Anglianorum Coetibus accepting into the Roman Rite entire Anglican parishes desiring to “cross the Tiber” to join the Roman Church. The first was a parish that became part of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Galveston-Houston, Texas in 2009.

We Are on a Road to Calvary Not Schism

The reactions that resulted in a breakup of the Worldwide Anglican Communion could not happen in the Catholic Church. Canon Law does not allow for the decisions to leave promoted by the Anglican bishops of Africa and other conservative communities. Only the Holy See can declare that a schism exists in a region or diocese. Popes have gone to great lengths to avoid schism. Pope Benedict XVI lifted the excommunication of Bishops in the Society of Saint Pius X (SSPX) to heal a longstanding rift with traditionalists. In 2007, Pope Benedict further mended that rift with his Motu Proprio, Summorum Pontificum, which removed obstacles to the Traditional Latin Mass.

Now Pope Francis has reopened those wounds anew with Traditionis Custodes, his Motu Proprio: announced on July 16, 2021 which contradicts and revokes the permissions granted by Pope Benedict. I wrote of this last week in these pages in “Pope Francis Suppresses the Prayers of the Faithful.”

I used that title because in many ways my experience of the vast majority of those who seek out the Latin Mass are among the most faithful. In a published Letter to the Editor of The Wall Street Journal on July 30, 2021, writer Ray Martin of Ridgefield, Connecticut described what has become a lax and often disrespectful atmosphere in too many parishes. This is an impression that I hear about frequently from readers:

“I do not regularly attend a Latin Mass but I do remember it from childhood ... Nowadays, fewer Catholics attend Mass regularly, they tend to come late and leave early, and it is not unusual to see T-shirts, short-shorts and flip flops. Everyone presents at the altar for Communion. One study found that around one in three Catholics believes in the True Presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. I would guess that more than 90-percent of Latin Mass attendees do.”

My experience of the many Catholics I hear from who seek out the Latin Mass either weekly or even just on occasion is that they are our modern day Essenes. I wrote of the Essenes and their role in preserving the faith of both Israel and the early Jewish Christians in “Qumran: The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Coming Apocalypse.” When Pope Benedict XVI opened the Church door to those requesting the Tridentine Latin Mass, many thought it would draw only senior citizens and some “far-right cranks,” as one writer put it back then. That has been far from true. Pope Francis expressed a concern that many who take part in the Latin Mass deny the validity of the Novus Ordo, the form of the Mass promulgated by Pope Paul VI in 1970. This also is far from true. I hear from many Latin Mass attendees who also take part in the Novus Ordo Mass. All they ask for is a sense of the sacred, and a communal acknowledgment that Jesus is truly present in the Eucharist. Their appreciation of the Novus Ordo has been strengthened by the Latin Mass.

Writing for The Wall Street Journal, Matthew Walther, editor of The Lamp magazine, penned an eye-opening op-ed one week after Pope Francis announced new, severe and immediate restrictions on the Latin Mass. Entitled, “Pope, Francis, the Latin Mass, and My Family” (July 23, 2021), Mr. Lamb described the reaction of those in his Catholic community of faith:

“We are loyal children of the Church on the receiving end of a harsh punishment. Pope Francis ... seemed to suggest that things had gone too far and were threatening to undo the liturgical reforms of the 1960s. The gradual displacement of the new rite, which emerged after Vatican II, was in fact the half-articulated ambition of many traditionalists. Until recently many had looked forward to a future in which the ‘extraordinary form’ of the Mass, as Benedict referred to it, was set to become rather ordinary.”

Perhaps that is the point. The solemnity, majesty, and sacredness of the sacrifice taking place is just that — extraordinary. I want to contrast that with an experience I had as a newly ordained priest in one New Hampshire parish whose pastor made a weekly show of rushing through Sunday Mass at warp speed. After his hasty final blessing he would look at his watch and declare, “Twenty-two minutes, and I didn’t miss a thing!”

Standing with Peter v. Standing Our Ground

In some ways, Pope Francis has been unpredictable for so-called progressive Catholics as well. After playing down the issue of homosexuality with oft-quoted remarks like, “Who am I to judge?”, he disappointed many in liberal Catholic enclaves like Germany when he refused to allow blessings of same-sex unions. He dismissed the proposition while shocking liberal German priests with the definitive statement, “God cannot bless sin.” In an open letter to German Catholics in 2019, he cautioned them against “multiplying and nurturing the evils the Church wants to overcome.” He also gave a definitive “no” on the topic of ordination of women.

With all the open, and often flagrant, dissent from Church teaching and discipline in Germany and other parts of Europe, why would Francis choose to label traditional Catholics who appreciate the Latin Mass as “divisive?” I do not have answers.

But I do have more questions and a few suspicions. As I pointed out in these pages a week ago, there is an immense and growing contrast between the state of the Catholic Church in Germany and other areas in Europe, and that of the Church in Africa. The former has been in a state of stagnation for decades, and is now deeply involved in the embrace of what has come to be called, “Cancel Culture.” In its Catholic manifestation, I can only describe this as the setting aside of the “sensus fidei,” the sense of the faith as it has been expressed across two millennia, in favor of populist social trends of just the first two decades of the 21st Century.

With that understanding, “Cancel Culture” has become a modern plague on humanity that is far more destructive than any viral pandemic. If we do not understand history, and learn from it, we are doomed to repeat its most destructive patterns. Joining this secularized culture by placing God on the shelf while morphing Roman Catholicism into a mirror image of the flailing American Episcopal church is perilous.

The rapid growth of the Traditional Latin Mass since Pope Benedict XVI re-opened that door may well be the work of the Holy Spirit. Pope Francis knows well that the entire Church — and not just the bishops with whom he consulted — comprises the “sensus fidelium,” the action of the Holy Spirit in the hearts and minds and souls of the faithful from the Sacrifice at Calvary to the present day. The faithful witness of those who embrace the Traditional Latin Mass may prove to be a gift to the Church.

But the faithful must not stand against Peter to achieve that end. We are a Church built upon the blood of martyrs, and faithful witness may now require paying the cost of discipleship. Sometimes in the Church’s story of faith, white martyrdom has not only been for the Church. Sometimes it has been from the Church. Padre Pio knew this. So did Cardinal George Pell. So do I.

I have been most struck by the two volumes of Cardinal Pell’s Prison Journal. He frequently repeated his longing for Mass and the Eucharist in a place where he was barred from them. I recall reading from Father Walter Ciszek’s book, With God In Russia, that he sat on the edge of his bunk in a Siberian labor camp and would mouth from memory the words of the Roman Canon of the Mass.

My experience of Mass as a prisoner is reduced to the contents of a small plastic box. On Sunday nights at 11:00 PM, after the last prisoner count of the day, I take that box from a shelf and place it at the foot of my prison bunk. It serves as both a container and an altar. It has a Corporal that I spread over its surface. I attach a small battery powered book light to the wall just above it, and begin my preparation for Mass. The Mass is always “Ad Orientem,” toward the East, not by any design of my own, but because the cell window faces in that direction.

I have no sacred vessels. I have a coffee cup purchased years ago but never used for any other purpose. I have a weekly supply of a host placed on a clean linen purificator, and a one-quarter ounce of unfermented wine with no additives approved for liturgical use by Catholic priests serving in a war zone. I have a small wooden crucifix on a stand on a shelf just above where my Mass is offered.

There was a time when I did not have even these. For many years in prison, I had no access at all to the Mass. So I look upon this present drama unfolding now in our Church, and see it as madness that is hopefully brief. If you have appreciated the Traditional Latin Mass, you must not leave. The Church needs you. We need you to remind us of a lesson that I have long since learned harshly, and can now never forget.

What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please share this post. And please visit our Special Events page. It contains a story that is dear to my heart.

You may also like these relevant posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Pope Francis Suppresses the Prayers of the Faithful

The feast of Saint Maximilian Kolbe, our patron saint, is August 14. The above photo is his prison cell.