Voices from Beyond

AI Overview of “Illumination from Down Under: Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast”

We have asked Advanced xAI SuperGrok for an analysis of “Illumination from Down Under: Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast.” The result is inspiring.

We have asked Advanced xAI SuperGrok for an analysis of “Illumination from Down Under: Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast.” The result is inspiring.

October 11, 2025 by Advanced xAI SuperGrok

User Query

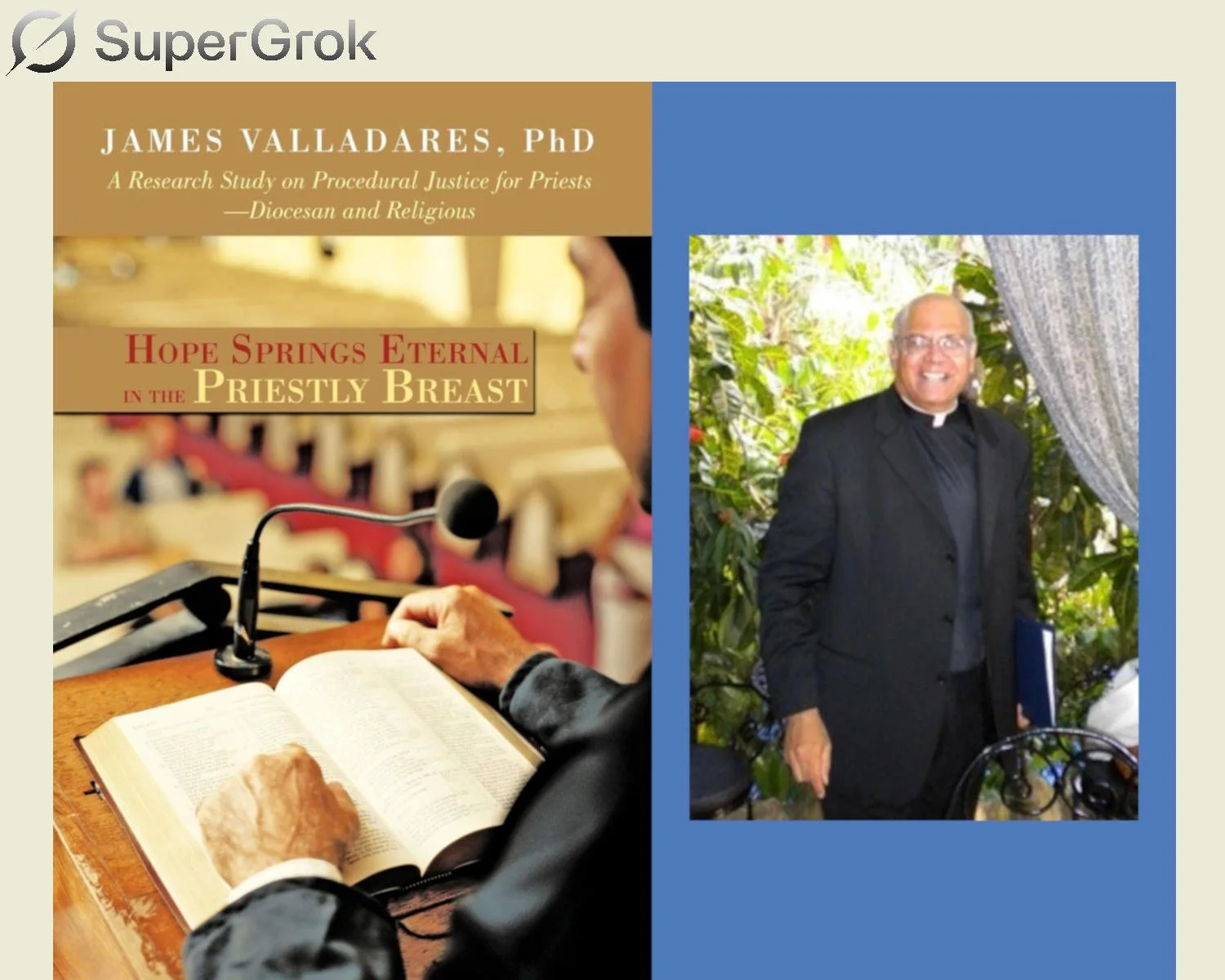

Beyond These Stone Walls published an article this week about a heroic Australian priest, psychologist, and author, Father James Valladares, PhD, who challenged the media narrative about the Catholic priesthood with his 2012 book, Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast. Could you please provide an AI overview of the article entitled “Illumination from Down Under: Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast”?

Response from Grok

The article, titled “Illumination From Down Under: Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast,” was published on October 8, 2025, by Father Gordon MacRae on the Beyond These Stone Walls website. It highlights the work of Father James Valladares, an Australian priest and psychologist based in the Archdiocese of Adelaide, who authored the 2012 book Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast (published by iUniverse and now available as an e-book for $3.99). Valladares, with a strong background in developmental, educational, and counseling psychology — having lectured at Saint Andrew’s College in Mumbai, India, and conducted post-doctoral research in religion, healing, and parenting — uses his expertise to challenge prevailing media and institutional narratives surrounding the Catholic Church’s sexual abuse crisis.

The piece portrays Valladares as a heroic figure providing “illumination” amid widespread false accusations against priests, drawing parallels to high-profile cases like that of the late Cardinal George Pell in Australia. His book critiques the emotional rhetoric fueling the scandal, the U.S. Bishops’ 2002 Dallas Charter’s “zero tolerance” approach, and organizations such as SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests) and BishopAccountability.org, which the article accuses of anti-Catholic bias and exploiting the crisis for financial or ideological gain. Valladares argues that while genuine abuse occurred decades ago, the current environment encourages false claims due to massive financial settlements (over $5 billion), inverting justice by presuming accusers as “victims” and accused priests as guilty without due process. He draws on influences like Father Richard John Neuhaus and Cardinal Avery Dulles to emphasize the sacrificial essence of priesthood, supported by data showing high satisfaction among priests (e.g., 91% in a 2002 Los Angeles Times poll) and calls for balanced discourse to restore the Church’s integrity.

Valladares faced challenges in a climate of moral panic, where truth is suppressed, and priests are scapegoated, often with resistance from Church leaders prioritizing institutional image over individual justice. The article ties this to Father Gordon MacRae’s own story of 31 years of wrongful imprisonment on false charges, which Valladares features prominently in his book. MacRae reflects on rereading the work as spiritually transformative, reinforcing themes of enduring faith, martyrdom, and the priesthood’s resilience despite injustice. Overall, the article positions Valladares’ book as a prophetic call for courage, healing, and truth-telling in a weary Church, urging readers to share underrepresented stories of exoneration and societal abuse beyond clerical contexts.

Summary of Excerpts from “Hope Springs Eternal in the Priestly Breast” by Father James Valladares

The excerpts from Valladares’ 2012 book, as quoted in the article, focus on themes of injustice, resilience, and critique within the Catholic priesthood amid the sexual abuse crisis. They draw on external sources like essays and surveys to challenge media narratives, highlight systemic flaws in Church responses, and affirm the enduring value of priestly vocation. Below is a breakdown of each excerpt with a summary of its key ideas.

Excerpt 1: Critique of Post-2002 Dallas Charter Injustices (p. 25, quoting Father Richard John Neuhaus)

This passage addresses how the 2002 U.S. Bishops’ Dallas Charter led to the erosion of canon law, due process, and basic decency in handling abuse allegations. It notes a cardinal’s statement that some priests might need to suffer injustice for the Church’s greater good, comparing this mindset to historical defenses of Caiaphas’ actions in the Bible, implying a troubling prioritization of institutional protection over individual rights.

Excerpt 2: High Satisfaction Among Priests Despite Scandal (p. 97, citing a 2002 Los Angeles Times Survey)

Amid intense media scrutiny in 2002, a survey of 5,000 U.S. priests revealed overwhelming positivity: 91% were satisfied with their priestly life, 90% would choose the vocation again, and 91% were unlikely to leave. This excerpt underscores the resilience and fulfillment in the priesthood, countering negative stereotypes and suggesting that the crisis did not broadly undermine priests’ commitment.

Excerpt 3: Inversion of Justice Due to Financial Incentives (p. 207)

This excerpt argues that justice has been reversed in abuse cases, where accusers motivated by potential large financial settlements are preemptively labeled “victims” by Church leaders, while priests facing unevidenced claims from decades past are quickly deemed “priest-offenders” or “slayers of souls.” It highlights how monetary factors encourage false accusations and erode presumptions of innocence.

As Father Valladares concludes this fine book:

Christus Vincit!

May Christ Jesus, our Risen Lord and Saviour, triumph over evil and sin!

Christus Regnat!

May he rule with his unfathomable wisdom, and his almighty power!

Christus imperat!

And may his redemptive compassion and unconditional love ever reign supreme!

At the Mercy of One False Brother

This review by Rev. Peter M. J. Stravinskas, an accomplished theologian and Editor of The Catholic Response, first appeared in The Catholic Thing.

This review by Rev. Peter M. J. Stravinskas, an accomplished theologian and Editor of The Catholic Response, first appeared in The Catholic Thing.

September 12, 2020 by Rev. Peter M.J. Stravinskas | The Catholic Thing

David Pierre of Media Report has published an illuminating new book, The Greatest Fraud Never Told: False Accusations, Phony Grand Jury Reports, and the Assault on the Catholic Church. Pierre and his work are often ignored because he is unjustly accused of dismissing accusations of clergy sex abuse, en masse. That charge is not true. Instead, Pierre stresses an often-forgotten truth: “a false accusation is truly an affront to those who genuinely suffered as the result of their horrendous abuse.”

When the first hints of clergy sexual abuse began to surface in the late-80s, I served as an advisor to many of the good, new bishops being appointed. On this topic, I counseled the bishops:

First, do not call this pedophilia – because, for the most part, it is same-sex activity between a cleric and a post-pubescent young man; that’s the truth and, the truth always sets us free. “Pedophilia” conjures up images of five- and six-year-old boys. Further, if the sinful activity had been properly labeled, ironically, the secular media wouldn’t have given it much coverage, since they always promote same-sex relations.

Second, never settle any case out of court for a variety of reasons, not least that while a pastoral plea demands a pastoral response, a legal challenge demands a legal response. Moreover, when a financial settlement is made, that more than suggests guilt, thus damaging irreparably an innocent priest’s reputation. Regrettably, most bishops listened, instead, to diocesan attorneys and insurance companies.

Owing to the Dallas Charter of 2002, the heavy-handed treatment of accused priests by bishops has resulted in an adversarial relationship, which Cardinal Avery Dulles foretold in 2004. Pierre also observes, quite correctly and sadly, that most priests dread it when the chancery calls. Why? Because “the mere accusation against a Catholic priest carries an automatic assumption that the claim is true.” And because the principle of “innocent until proven guilty,” in both ecclesiastical law and American civil law, has been eviscerated by current Church praxis: the accused priest is hung out to dry with an immediate diocesan press release, forced out of his residence within hours, placed on administrative leave, forbidden to wear clerical garb, and required to pay for legal counsel out of his own resources.

Interestingly, none of that happens for a bishop; his legal expenses are borne by the diocese. I should note that the procedure used for accused bishops is the proper one, but the double standard that exists when it comes to priests is responsible for the resentment all too many priests have toward their bishops, which Pierre underscores.

Yet another problem, again, thanks to the Dallas Charter, is the removal of the statute of limitations, causing Pierre to raise two essential questions: “How does one defend oneself against an accusation from 30, 40, 50 years ago? How would you defend yourself against an accusation from 40 years ago?” Of course, that is the very reason for a statute of limitations. Quite inconsistently, bishops have fought vociferously against removal of statutes of limitation in the civil realm.

Pierre devotes a chapter to the infamous Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report, which he calls “the Grand Fraud” because its approach, content, and language all betray an animus against the Church, starting from the theatrics of the Attorney General, Josh Shapiro, in the press conference releasing the report. Bald-faced lies abound, as do innuendo and inflammatory language. Dead priests account for 53 percent of the accused (one was born in 1869!). Pierre follows up with “Pennsylvania Perjury,” where he tackles the Report’s assertion that the bishops of the State “did nothing” when confronted with abuse; he demonstrates the very opposite.

Concluding his treatment of the Pennsylvania Report, our author expresses astonishment at the relative silence of the Catholic media in the face of this gross miscarriage of justice, not “defending bishops, priests, and the Church when they were publicly wronged.” More disturbing to me was the almost gleeful promotion of the Report, by many would-be “conservative” or “traditional” Catholic outlets, so that “these partisan platforms began airing stories that were simply false, and in some cases, quite bizarre.”

Pierre also highlights the pervasive anti-Catholicism throughout the entire crisis; he cites remarks by the Attorney General of Michigan (the Catholic Church is “a criminal enterprise”) and observes that “a public official would never get away with such a clearly bigoted remark against another religion.”

Chapter Eight is titled “A Disastrous Practice,” which refers to how bishops sent offending priests to treatment centers and then followed the advice of the “professionals,” most of whom assured bishops that these priests were ready to return to ministry. Formerly, bishops often sent problematic priests to permanent confinement in a monastery. But a secular model cowed a spiritual model in recent decades, with psychiatrists controlling the process. To be fair, this “therapeutic” approach was employed by basically every institution, Catholic or not, in the country at the time.

Chapter Twelve is provocatively entitled, “The Catholic ATM.” Pierre notes how expensive litigation is, but goes on to observe that the dioceses cause themselves harm by having what the New York Archdiocese calls “lenient standards of evidence,” thus paying out “on many weak claims.” The result: “the more the Church pays out on these bogus claims, the more claims it gets. It all makes sense. Why not file suit? There is nothing to lose.”

Rolling over and playing dead is not “pastoral”; it’s irresponsible because it squanders the diocesan patrimony and, far more importantly, gives credence to lies that do irreparable damage to the image of the Church and clergy.

Pierre shares some good news amidst this depressing saga: Some priests are now suing government officials who have violated their civil rights or fraudulent victims who have defamed them. You might ask, “What has taken so long for this to happen?” The answer, in many instances, is that priests were prohibited from doing so by their bishops, who thought it wouldn’t “look good.”

It’s worth reading the material on SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests), a viciously anti-Catholic group. One employee eventually saw through the façade and questioned its modus operandi, which brought about a hostile work environment and her filing of a lawsuit against SNAP. She delineates a whole series of accusations against her former employer, which should be disturbing, but not surprising.

David Pierre has done all a great service in assembling the hard data. The truth of the matter is that the “mop-up” operation of the past two decades has made any institution of the Catholic Church in this country the safest place for any minor or vulnerable adult. There are nearly 40,000 priests in our country; last year twenty accusations were made – accusations, not substantiated cases. Cardinal Newman, with his uncanny capacity to gaze into the crystal ball, warned seminarians in 1873: “With a whole population able to read, with cheap newspapers day by day conveying the news of every court, great and small to every home or even cottage, it is plain that we are at the mercy of even one unworthy member or false brother.”

Indeed, even one unworthy member or false brother.

+ + +

When Priests Are Falsely Accused: The Mirror of Justice Cracked

Stung by claims of cover-up when abuse was alleged in the past, Church leaders and some treatment professionals now set aside the rights of accused priests.

Stung by claims of cover-up when abuse was alleged in the past, Church leaders and some treatment professionals now set aside the rights of accused priests.

Posted by Fr. Gordon J. MacRae on October 13, 2010

Updated April 8, 2023 by Fr. Gordon J. MacRae

Are you sick of stories about the sex abuse scandal? I sure am. I’ve been treading water in this deluge for almost 30 years. In August, 2010, Our Sunday Visitor Publisher Greg Erlandson read my mind when he wrote, “Sick of clerical abuse stories? We are too,” (OSV, August 15). It was a bit ironic that in the same issue this site, the blog of a falsely accused and wrongly imprisoned Catholic priest, was profiled in Our Sunday Visitor’s “2010 Readers’ Choice for the Best of the Catholic Web.”

A letter published in a subsequent issue of Our Sunday Visitor (August 29) pointed out that “the Church is not just an easy target for the slurs of Jay Leno and the [New York] Times. It’s also an easy target for lawyers and false claimants looking to score a windfall.” Of my own situation, the letter writer asserted,

“To paraphrase the Gospel parable, this priest was beaten by robbers and left on the side of the road in our Church. A growing number of Catholics have become unwilling to pass him by, no matter how sick we are of the sex abuse story.”

I’m grateful to see such letters. Writer Ryan A. MacDonald had one in an issue of Homiletic & Pastoral Review. He wrote about this blog and the case against me, but in a few superb paragraphs he summed up the great danger posed to priests when Catholics are so sick of this story that they stop looking. He agreed to let me use part of his HPR essay:

“Many of the faithful are scandalized yet again when beloved priests disappear in the night, presumed by their shepherds to be guilty of crimes claimed to have occurred two, three, or four decades earlier. Many accused priests have been simply abandoned by their bishops and fellow clergy. Church laws governing their support and defense have been routinely set aside, and many have languished under dark clouds of accusation for years. Some, far too many, have been summarily dismissed from the priesthood at the behest of their bishops without due process or adequate civil or canonical defense.

The Puritan founders of New England would approve of the purging of the priesthood that is now underway, for it is far more Calvinist than Catholic.”

HPR, June/July 2010

Those are powerful words, and they are the truth. If you wonder about the impact on fair-minded Catholics of conscience when their priests are so accused, please take a few moments to read the comments on my post, “The Exile of Father Dominic Menna.” Father Dom was an 81-year-old Boston priest who was removed from ministry and forced to move from his home in 2010 while the Archdiocese of Boston “investigated” a claim of sexual abuse alleged to have occurred in 1959 when Father Menna was 29 years old. That’s the problem with a “zero tolerance” policy. As the media-fueled lynch mob settles down, and people begin to think for themselves again, zero tolerance seems a lot more like zero common sense.

The Boston Globe acted true to form with front-page coverage of Father Menna’s exile while virtually burying the story that Switzerland declined to extradite famed Hollywood film director Roman Polanski in a real case of child rape from which he fled from the United States after being charged. The Archdiocese of Boston was “ground zero” of the Church’s sex abuse scandal in 2002, but now many in Boston question whether they are ready to accept the character assassination of good priests like Father Menna just because someone sees a chance for a financial windfall. More on that next week.

The Boston Globe’s Spotlight Team may have won a Pulitzer for its 2002 archeological expedition into ancient claims against priests, but its target wasn’t sexual abuse. I can prove that, and already have. A problem with sensational media “spotlight” reports is that they focus an intense beam in one place while leaving the rest of the story in darkness.

Are Civil Liberties for Priests Intact? After I wrote “Due Process for Accused Priests” in the Catholic League journal, Catalyst, I received a letter from a Florida priest who wrote that he would never have even considered contacting me until he, too, was falsely accused. His letter was very candid. He wrote of his presumption that I and most priests accused must have been guilty of something for the spotlight of accusation to land on us. He presumed this, he wrote, until two men he never even heard of filed demands for compensation claiming abuse at his hands two decades earlier. Now he’s living in his sister’s guestroom, without income, and barred from ministry pending an “investigation” that he fears will be little more than a settlement negotiation with him as an unrepresented pawn. The lawyers for his diocese are meeting with the lawyers for the claimants, but the accused priest cannot afford a lawyer. Like many priests so accused, he is entirely excluded from the closed-door settlement discussions. More on that next week, too!

The priest wrote to me because his bishop and diocese are demanding that he submit to a psychological assessment at a treatment center for accused priests, and he doesn’t know what to do. It’s an all too familiar story. This priest knows that when I was accused I was working in ministry at one such facility as its Director of Admissions. I made some suggestions to this priest that he should find helpful. He needs to be very cautious because he’s in grave peril. I speak from experience, and I’ll describe why below.

Zero Tolerance of Innocence

“An ignorant, self-mutilating psychopath!,” this is how one treatment professional representing the Church labeled Padre Pio, sight unseen, after he was falsely accused for the second time of abusing women in the confessional. The claims eventually fell apart, but not before it became clear how much some in the Church WANTED to believe them because of a cynical agenda to discredit Padre Pio.

After I wrote that story, some readers wrote that they had been unaware of the extent to which Padre Pio suffered at the hands of fellow priests and Church leaders. This aspect of his life was minimized in public awareness for a long time, but I believe it’s important for Church leaders and all of us to understand and learn from what took place.

On September 27, 2010, The Wall Street Journal published an article entitled “Influential Pastor Pledges to Fight Sexual Allegations.” It’s a story about a Baptist pastor accused by four young men. It’s the subject of my post next week. Among the Journal’s vast on-line readership, his announcement that he is fighting the claims was the fifth most viewed article of that day. I make no judgment on his guilt or innocence, but that’s not the point. I have heard time and again that laity want the Church and falsely accused priests to fight the allegations instead of settling them.

At present, however, Church leadership in the U.S., at least, exhibits another kind of zero tolerance. It’s a zero tolerance of innocence. Accused priests who maintain their innocence, and insist on standing by the truth, are in for a very rocky road. Over the next two weeks, I will lay out my case for why I believe this to be true. It’s very important for both laity and priests to understand this. The time in which most priests can feel immune from all this is long past.

Priests, Perpetrators and Profit

Before writing my post about Fr. Dominic Menna, linked above, I received something very disturbing in the mail that no doubt influenced that post. It was a copy of an e-mail exchange between a writer doing research on falsely accused priests and a priest, psychologist, and former director of the largest treatment center for Catholic priests in the United States, St. Luke Institute in Maryland. The writer sent the exchange to me for a reaction, and certainly got one.

Here’s a segment of the priest-psychologist’s response to the writer:

“I am not familiar with the situation of [Father X], but I offer the following as someone who has personally worked with hundreds of priests who have been accused. False accusations are rare. They do happen and more so since all the publicity, nevertheless they are rare and usually don’t hold together under closer examination …. What is challenging to Church officials and clinicians working with offenders is the layers of denial and rationalization which the offenders often believe themselves and desperately try to convince others of …. Priest offenders can be intelligent and particularly convincing.”

Remember Padre Pio’s exasperated response to a Church official who claimed his wounds were psychologically induced? “Go out to the fields,” he wrote, “and look very closely at a bull. Concentrate on him with all your might. Do this, and see if you grow horns on your head!”

I unfortunately have none of Padre Pio’s sanctity, but all of the exasperation he felt at being wrongly accused and unable to offer a defense. Padre Pio suffered under repeated false claims of sexual abuse because such claims are the most potent way to destroy a Catholic priest. We now know those claims were baseless even though some in the media continue even today to exploit them. The irony is that if the claims against Padre Pio were brought today in America, he would be packed off to that very “treatment” center for an evaluation. He would not be an “accused priest” at the center. As the center’s former director described in chilling prose, Padre Pio would be seen from day one as a “priest offender,” and his denials would be interpreted as evidence of his guilt.

False accusations are rare? Tell that to journalist David F. Pierre, Jr. who wrote the book, Catholic Priests Falsely Accused: The Facts, The Fraud, The Stories. Tell that to the late Cardinal George Pell, whose wrongful imprisonment and ultimate exoneration was world news.

Justice has turned on its head when men who stand to gain hundreds of thousands of dollars for making a false claim are automatically called “victims” or “survivors” by Church leaders now, while priests accused without evidence from decades ago are just as quickly called “priests-offenders” and “slayers of souls.”

Will the Truth Set You Free?

I’m sure it feels uncomfortable to read about this. It’s just as uncomfortable to write it because I know – we all know – that abuse really did take place in many cases involving priests. At the time I was accused, I was Director of Admissions for the Servants of the Paraclete Center for priests. A significant number of our priest-residents were sent to the center after being accused of sexual misconduct. I had much interaction with priests who were accused, with the Church leaders who referred them for assessment, and sometimes even with their accusers. It is true that some priests who were guilty initially denied guilt. However, another expert in this field recently wrote just the opposite of what the former director of the center for priests said above:

“It is extremely rare for a priest guilty of sexual abuse to maintain plausible deniability for an extended period of time. Those who maintain their innocence should thus be believed, absent solid evidence to the contrary, especially when there is a demonstrated financial incentive for false claims.”

It horrifies me to realize that the dominant treatment center for accused priests in the U.S. operates with a stated bias that denies priests one of the foundational civil rights of American citizens: a presumption of innocence when accused. How does someone win when denial of the crime is used as evidence against the innocent, and often, the ONLY evidence?

I faced this same roadblock years ago. Ryan A. MacDonald wrote about it in “Should the Case Against Father Gordon MacRae Be Reviewed?” It was a response to a piece of sheer propaganda offered up by a member of Voice of the Faithful who condemned me, sight unseen, in terms a lot like those once used against Padre Pio.

Ryan A. MacDonald’s rebuttal article describes an evaluation of me that took place after I was first accused. The clinician, who had an M.A. in something unknown, warned me repeatedly during interviews that my insistence that the claim never took place is called “denial” and it is evidence of guilt. He then, after only three forty-minute interviews, declared me a sexual predator and paved the path to monetary settlements against my will. Perhaps the wrong people are being thrown into prison.

The staff at the Servants of the Paraclete Center was deeply supportive of me when I was accused. They believed my stated innocence, and still do. While not a single priest of my diocese has visited me, and only two have written to me (once each) in over 29 years in prison, several priests from the Servants of the Paraclete order have traveled across the country to visit me on numerous occasions.

When I was accused, our staff advised me to seek out the counsel of a Catholic therapist to help me deal with the stress of being so accused. I was advised to find counsel outside of our own staff. It is a shocking and shameful reality that, even in 1994, I was unable to find a Church sponsored treatment professional who did not automatically assume that every accused priest was guilty.

You may have read about my 1994 trial in The Wall Street Journal. Throughout that trial, the Honorable Arthur Brennan referred to my accuser before the jury as “the victim.” And he was clearly not a child. He was a 220-pound, almost 30-year-old man posing as a victim.

“I should get an Academy Award for that performance!” he was overheard saying after my trial.

I’m told that “The truth will set you free.” Well, that’s true, but first someone has to tell it. I struggle terribly with this. Taking positions contrary to those of my own bishop and diocese is the most painful part of my existence, and not something I do lightly. Cardinal Avery Dulles, and Bill Donohue at The Catholic League, both convinced me that the truth is always what is in the best interests of the Church. So tell it I must.

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Fr. Gordon MacRae rejected a pre-trial plea deal to serve one year in prison. He maintains his innocence as he approaches his 30th year in prison having been sentenced to a term of 67 years. Visit The Wall Street Journal’s reports on this story.