Voices from Beyond

The Legacy of “Billy Doe”

“The next time you hear a prosecutor making shocking allegations against the Church, remember the Billy Doe story and the corrupt D.A. who staged a witch hunt.”

“The next time you hear a prosecutor making shocking allegations against the Church, remember the Billy Doe story and the corrupt D.A. who staged a witch hunt.”

By Ralph Cipriano | Catalyst (January/February 2019)

With the Catholic Church under legal assault by prosecutors in 14 states, the case of a former Philadelphia altar boy dubbed “Billy Doe” serves as a cautionary tale that not every priest accused of sex abuse is automatically guilty.

The case also shows that crusading prosecutors don’t always play by the rules. And that no matter what the true facts in a sex abuse case are, it won’t matter to a biased news media.

Billy Doe, whose real name is Danny Gallagher, came forward at age 23 in 2011 to claim that back when he was 10 and 11 years old, he was repeatedly raped by two priests and a parochial school teacher. A couple of juries convicted all three attackers and sent them to jail. Also convicted was Msgr. William J. Lynn, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s former secretary for clergy. He became the first Catholic administrator in the country to be jailed in the clergy sex scandals, not for touching a child, but for endangering a child’s welfare by failing to protect the altar boy from a priest who was a known abuser.

In a civil settlement, the church subsequently paid Gallagher $5 million.

There was only one problem — Gallagher, a former drug addict, heroin dealer, habitual liar, third-rate conman and thief, made the whole story up. And all four men who went to jail — including a priest who died there — were innocent.

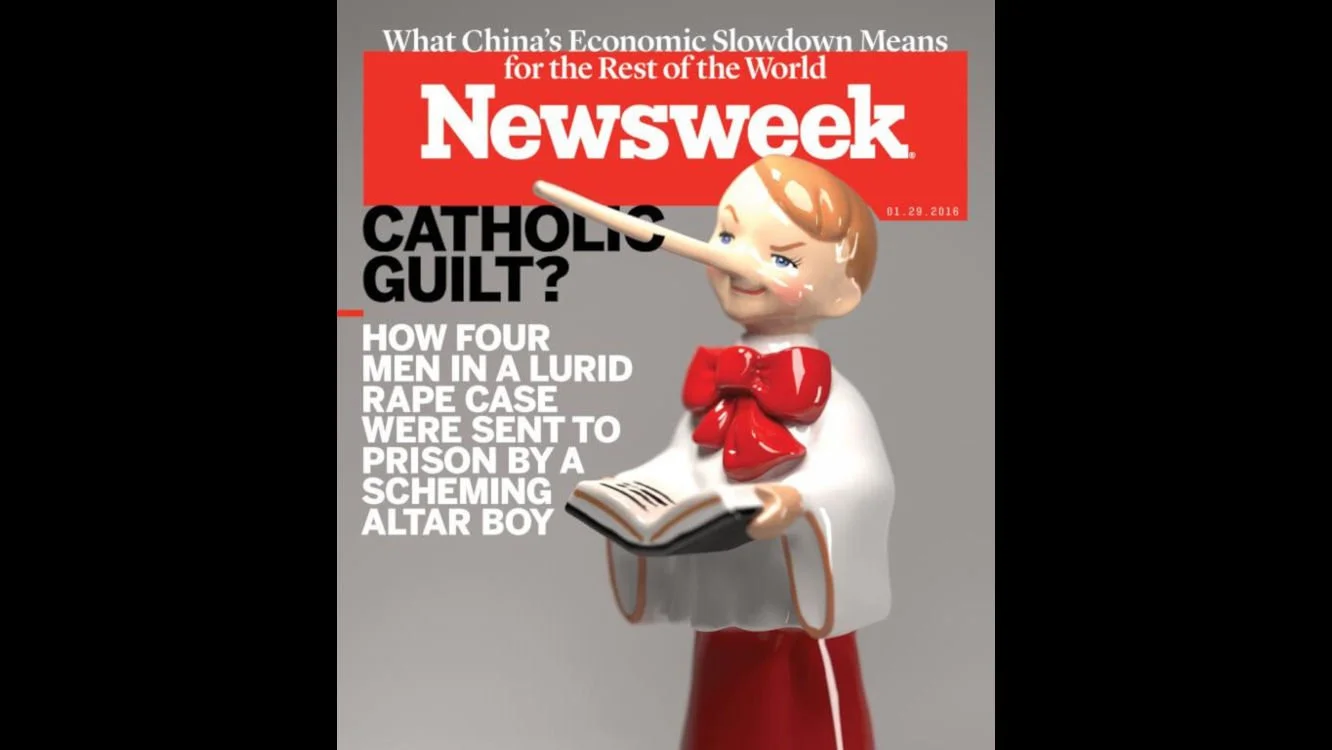

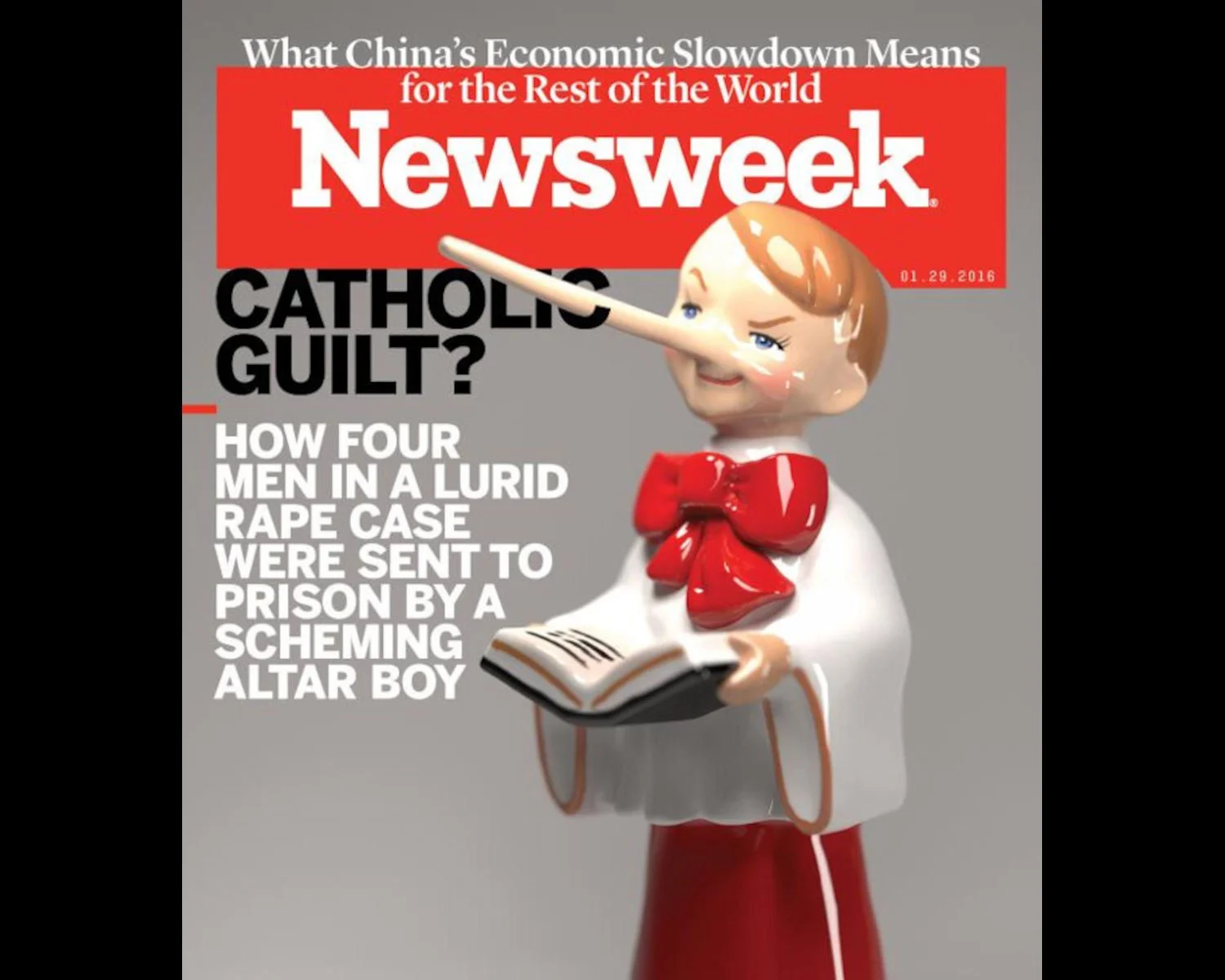

How do we know? On my blog, bigtrial.net, and for Newsweek and the National Catholic Reporter, I spent the past six years documenting all the holes in Gallagher’s outrageous and constantly changing tales of abuse.

I will now have to relate some graphic details to explain what a liar Gallagher is. And how irresponsible it was for former Philadelphia District Attorney Rufus Seth Williams to have put Gallagher on the witness stand as his star witness at two criminal trials in the D.A.’s self-described “historic” prosecution of the Church.

When he first came forward to tell two social workers for the archdiocese his accusations of abuse, Danny Gallagher claimed that:

• Father Charles Engelhardt attacked him in the sacristy after an early morning Mass, locked all the doors and then proceeded to pound away at the boy for five hours of brutal anal sex. Afterwards, Gallagher claimed the priest threatened to kill him if he told anybody about it.

• Father Edward V. Avery “punched him in the head,” and knocked him unconscious. When he woke up in a storage closet at the church, Gallagher claimed he was naked and tied up with altar sashes. Gallagher further claimed that Avery anally raped him so brutally that he bled for a week. And that the priest forced the boy to suck blood off the priest’s penis.

• Bernard Shero, Gallagher’s homeroom teacher, allegedly punched Gallagher in the face and strangled him with a seat belt before he allegedly raped the boy in the back seat of the teacher’s car. Afterwards, the teacher supposedly threatened to make the boy’s life a “living hell” if he told anybody.

But when Gallagher retold his story of abuse to the police and the grand jury, every detail I just mentioned — the anal rapes, the punches, the threats, the claims about being tied up naked with altar sashes, strangled with a seatbelt, and forced to suck blood off of a priest’s penis — all those graphic details were dropped from his story.

Instead, Gallagher spun a completely new fable about being forced by his attackers to view pornography and perform strip teases to music, and then engage in oral sex and mutual masturbation. In the civil courts, when Gallagher was confronted with all of the glaring contradictions in his conflicting tales of abuse, he responded by saying he couldn’t remember more than 130 times.

If this wasn’t enough evidence that Gallagher wasn’t credible, in 2017, Joe Walsh, the retired lead detective in the case, came forward to file a startling, 12-page affidavit. In the affidavit, Walsh stated that while questioning Gallagher pre-trial, he repeatedly came to the conclusion that the star witness was a liar, and that none of the alleged rapes ever really happened.

Walsh stated that while questioning Gallagher, the detective caught the former altar boy in one lie after another. According to Walsh, Gallagher finally admitted that with the social workers he “just made up stuff and told them anything.”

None of the facts about Walsh’s pre-trial grilling of Gallagher, however, were ever revealed to defense lawyers.

The retired detective also stated in his affidavit that during his investigation, he repeatedly told the lead prosecutor, former Assistant District Attorney Mariana Sorensen, that all the witnesses he interviewed, including members of Gallagher’s own family, and all the evidence he gathered, contradicted Gallagher’s cockamamie tales of abuse. Sorensen, however, stubbornly kept saying that she believed Gallagher. And when Walsh persisted, according to the detective, Sorensen replied, “You’re killing my case.”

In a subsequent bombshell, it was discovered that the prosecution hid more evidence from the defense and repeatedly lied about it. In 2010, when the D.A.’s office first interviewed Gallagher, former ADA Sorensen took seven pages of notes. And then she buried them. Over the years, Sorensen and two other prosecutors stood up in three different courtrooms, in front of three different judges, and stated that the notes didn’t exist.

But earlier this year, seven pages of Sorensen’s typewritten notes mysteriously reappeared. We also know that the prosecution also hid seven pages of notes taken by Church social workers that showed that when he first came forward, Gallagher wasn’t interested in pressing charges against anybody; he just wanted to find a lawyer so he could get paid.

Meanwhile, an appeals court overturned Msgr. Lynn’s conviction after he had served 33 months of his 36-month sentence, plus 18 months of house arrest. But despite Lynn’s jail time previously served, Gallagher’s complete lack of credibility, and Detective Walsh’s testimony about prosecutorial misconduct, a new Philadelphia district attorney, Larry Krasner, has decided he will retry the case next year.

And what about the media, which trumpeted the arrests, indictments and convictions of the three priests and former schoolteacher? How has the media covered all the bombshells that showed the prosecution of the Church was a sham?

By stonewalling, and willfully ignoring it.

The Philadelphia Inquirer, which in the past seven years has printed 64 news articles and editorials on the Billy Doe case, always presenting him as a legitimate victim of sex abuse, never outed Gallagher, or told readers that he was a fraud.

And then there’s Rolling Stone. Remember Sabrina Rubin Erdely, the reporter who fabricated a story about an alleged gang rape by seven men at a frat house at the University of Virginia by relying on the false accusations of a woman named “Jackie?”

Before she got conned by Jackie, Erdely was fooled by Billy. In 2011, Erdely wrote “The Catholic Church’s Secret Sex-Crime Files,” which accepted as gospel Billy Doe’s fraudulent tales of abuse. The reporter also hid that when she wrote the story she had an undisclosed conflict of interest — her husband was an assistant Philadelphia district attorney who worked for the D.A. that was prosecuting Billy’s alleged attackers.

Rolling Stone, which retracted the UVA rape story, has never retracted or even corrected Erdely’s fake story about the Church, which is still posted online.

How’s that for a fair and responsible media?

So this summer, when Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro announced the results of his secret grand jury investigation into sex abuse in six Pennsylvania dioceses, I wasn’t surprised that the media covered ancient accusations of abuse as though it had all just happened yesterday.

The Inquirer, which never got around to telling its readers that Billy Doe was a fraud, ran the grand jury story on its front page, cranking out a total of seven news stories and a column that blasted the Church.

Now we all know that the Catholic Church for decades was guilty of committing horrendous crimes against children, and also guilty of covering it up. But that doesn’t mean the media should suspend its judgment when it comes to holding prosecutors accountable.

When I read that grand jury report, it was like a tour through an ecclesiastic graveyard. Of 250 accused predator priests, at least 117 were dead. Another 13 priests born before 1940 had the dates of their deaths listed as unknown.

The oldest priest who was allegedly a predator was born in 1869, four years after the Civil War ended. Another alleged predator priest had been dead since 1950.

The alleged crimes detailed in the report were from as far back as the 1940s; one alleged victim was 83.

The grand jury report came with plenty of lurid charges. Such as the allegation that in 1969, Father Gregory Flohr had allegedly used a rope to tie up an altar boy in the confessional before sodomizing him with a crucifix.

Father Flohr could not be reached for comment; he’s been dead for 14 years.

But none of this mattered to the media; the Shapiro grand jury report that should have run on the History Channel made headlines nationally and internationally. It also inspired prosecutors in 14 states, as well as in the District of Columbia, to announce plans to launch their own investigations of the Catholic Church.

And why not? The Church is a sitting duck. Under ancient Vatican rules, each diocese is required to keep written records of all accusations against priests, whether they’re true or false. All an ambitious prosecutor needs for a fresh set of headlines and a room full of reporters at his next press conference is a judge willing to grant a subpoena to open the so-called secret archive files, just like Shapiro did.

Whether any of the lurid allegations a prosecutor makes will be subject to due process — and only a couple of Shapiro’s thousands of alleged crimes fell within the statute of limitations — doesn’t seem to matter.

So the next time you hear a prosecutor making shocking allegations against the Church, remember the Billy Doe story. And the corrupt D.A. in Philadelphia who used a fraudulent witness to stage a modern-day witch hunt.

These days, former Philly D.A. Rufus Seth Williams wears an orange jumpsuit. He’s sitting in a federal prison after pleading guilty in 2017 to a federal corruption case where he admitted to a crime wave that included taking bribes, misusing campaign contributions, and stealing from his own mother.

But Williams has never been prosecuted for the worst crimes he ever committed, namely what he did in the Billy Doe case to a blind lady named Justice.

Four men — three priests and a schoolteacher — were sent to jail on false charges. And one of those men, Father Engelhardt, who needed a heart operation, died in prison.

The priest spent his last hours handcuffed to a hospital bed, and in a dying declaration, still professing his innocence.

+ + +

Ralph Cipriano is a muckraking reporter who has written for the Los Angeles Times and the Philadelphia Inquirer. His blog posts on the trashing of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia by prosecutors and reporters can be found on the website “Big Trial.”

+ + +

Please visit and share this companion article by Father Gordon MacRae at Beyond These Stone Walls:

Fr Charles Engelhardt’s Indicted Prosecutor Took a Plea Deal

At the Mercy of One False Brother

This review by Rev. Peter M. J. Stravinskas, an accomplished theologian and Editor of The Catholic Response, first appeared in The Catholic Thing.

This review by Rev. Peter M. J. Stravinskas, an accomplished theologian and Editor of The Catholic Response, first appeared in The Catholic Thing.

September 12, 2020 by Rev. Peter M.J. Stravinskas | The Catholic Thing

David Pierre of Media Report has published an illuminating new book, The Greatest Fraud Never Told: False Accusations, Phony Grand Jury Reports, and the Assault on the Catholic Church. Pierre and his work are often ignored because he is unjustly accused of dismissing accusations of clergy sex abuse, en masse. That charge is not true. Instead, Pierre stresses an often-forgotten truth: “a false accusation is truly an affront to those who genuinely suffered as the result of their horrendous abuse.”

When the first hints of clergy sexual abuse began to surface in the late-80s, I served as an advisor to many of the good, new bishops being appointed. On this topic, I counseled the bishops:

First, do not call this pedophilia – because, for the most part, it is same-sex activity between a cleric and a post-pubescent young man; that’s the truth and, the truth always sets us free. “Pedophilia” conjures up images of five- and six-year-old boys. Further, if the sinful activity had been properly labeled, ironically, the secular media wouldn’t have given it much coverage, since they always promote same-sex relations.

Second, never settle any case out of court for a variety of reasons, not least that while a pastoral plea demands a pastoral response, a legal challenge demands a legal response. Moreover, when a financial settlement is made, that more than suggests guilt, thus damaging irreparably an innocent priest’s reputation. Regrettably, most bishops listened, instead, to diocesan attorneys and insurance companies.

Owing to the Dallas Charter of 2002, the heavy-handed treatment of accused priests by bishops has resulted in an adversarial relationship, which Cardinal Avery Dulles foretold in 2004. Pierre also observes, quite correctly and sadly, that most priests dread it when the chancery calls. Why? Because “the mere accusation against a Catholic priest carries an automatic assumption that the claim is true.” And because the principle of “innocent until proven guilty,” in both ecclesiastical law and American civil law, has been eviscerated by current Church praxis: the accused priest is hung out to dry with an immediate diocesan press release, forced out of his residence within hours, placed on administrative leave, forbidden to wear clerical garb, and required to pay for legal counsel out of his own resources.

Interestingly, none of that happens for a bishop; his legal expenses are borne by the diocese. I should note that the procedure used for accused bishops is the proper one, but the double standard that exists when it comes to priests is responsible for the resentment all too many priests have toward their bishops, which Pierre underscores.

Yet another problem, again, thanks to the Dallas Charter, is the removal of the statute of limitations, causing Pierre to raise two essential questions: “How does one defend oneself against an accusation from 30, 40, 50 years ago? How would you defend yourself against an accusation from 40 years ago?” Of course, that is the very reason for a statute of limitations. Quite inconsistently, bishops have fought vociferously against removal of statutes of limitation in the civil realm.

Pierre devotes a chapter to the infamous Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report, which he calls “the Grand Fraud” because its approach, content, and language all betray an animus against the Church, starting from the theatrics of the Attorney General, Josh Shapiro, in the press conference releasing the report. Bald-faced lies abound, as do innuendo and inflammatory language. Dead priests account for 53 percent of the accused (one was born in 1869!). Pierre follows up with “Pennsylvania Perjury,” where he tackles the Report’s assertion that the bishops of the State “did nothing” when confronted with abuse; he demonstrates the very opposite.

Concluding his treatment of the Pennsylvania Report, our author expresses astonishment at the relative silence of the Catholic media in the face of this gross miscarriage of justice, not “defending bishops, priests, and the Church when they were publicly wronged.” More disturbing to me was the almost gleeful promotion of the Report, by many would-be “conservative” or “traditional” Catholic outlets, so that “these partisan platforms began airing stories that were simply false, and in some cases, quite bizarre.”

Pierre also highlights the pervasive anti-Catholicism throughout the entire crisis; he cites remarks by the Attorney General of Michigan (the Catholic Church is “a criminal enterprise”) and observes that “a public official would never get away with such a clearly bigoted remark against another religion.”

Chapter Eight is titled “A Disastrous Practice,” which refers to how bishops sent offending priests to treatment centers and then followed the advice of the “professionals,” most of whom assured bishops that these priests were ready to return to ministry. Formerly, bishops often sent problematic priests to permanent confinement in a monastery. But a secular model cowed a spiritual model in recent decades, with psychiatrists controlling the process. To be fair, this “therapeutic” approach was employed by basically every institution, Catholic or not, in the country at the time.

Chapter Twelve is provocatively entitled, “The Catholic ATM.” Pierre notes how expensive litigation is, but goes on to observe that the dioceses cause themselves harm by having what the New York Archdiocese calls “lenient standards of evidence,” thus paying out “on many weak claims.” The result: “the more the Church pays out on these bogus claims, the more claims it gets. It all makes sense. Why not file suit? There is nothing to lose.”

Rolling over and playing dead is not “pastoral”; it’s irresponsible because it squanders the diocesan patrimony and, far more importantly, gives credence to lies that do irreparable damage to the image of the Church and clergy.

Pierre shares some good news amidst this depressing saga: Some priests are now suing government officials who have violated their civil rights or fraudulent victims who have defamed them. You might ask, “What has taken so long for this to happen?” The answer, in many instances, is that priests were prohibited from doing so by their bishops, who thought it wouldn’t “look good.”

It’s worth reading the material on SNAP (Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests), a viciously anti-Catholic group. One employee eventually saw through the façade and questioned its modus operandi, which brought about a hostile work environment and her filing of a lawsuit against SNAP. She delineates a whole series of accusations against her former employer, which should be disturbing, but not surprising.

David Pierre has done all a great service in assembling the hard data. The truth of the matter is that the “mop-up” operation of the past two decades has made any institution of the Catholic Church in this country the safest place for any minor or vulnerable adult. There are nearly 40,000 priests in our country; last year twenty accusations were made – accusations, not substantiated cases. Cardinal Newman, with his uncanny capacity to gaze into the crystal ball, warned seminarians in 1873: “With a whole population able to read, with cheap newspapers day by day conveying the news of every court, great and small to every home or even cottage, it is plain that we are at the mercy of even one unworthy member or false brother.”

Indeed, even one unworthy member or false brother.