Finding Your Peace: Job and the Mystery of Suffering

The problem of evil and the pain of suffering plagued humanity from our beginning. How do we reconcile grace and hope in a loving God in the midst of suffering?

January 31, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

On the Fifth Sunday of Ordinary Time, ten days before Ash Wednesday this year, the assigned First Reading at Mass is from the Book of Job. It is Job’s lament against suffering, and the reading ends on a dismal note: “My days are swifter than a weaver’s shuttle; they come to an end without hope. Remember that my life is like the wind. I shall not see happiness again.” Job 7:6-7

In the Book of Job, you will have to suffer along with him through a lot more of his lament until you come to God’s response many chapters later. As I read the lament I marveled at how much of it I can relate to. As I wrote in a post just a week ago, my days are often faced without obvious hope. But I also marvel at how much I can relate to God’s response to Job.

I wrote a science post in 2022 entitled “The James Webb Space Telescope and an Encore from Hubble.” Longtime readers of this blog know of my enthusiasm for Astronomy and Cosmology. If I were God — and thank God I am not — I would have framed my answer to Job just as God did:

“Who is this that obscures divine plans with such words of ignorance? Where were you when I laid the foundations of the Earth? Have you ever in your life commanded the morning or shown the dawn its place? Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades, or loose the cords of Orion?”

— Job 38: 2,4,12,31

Job got the message. So did I, and it isn’t trite at all. The response of God was twofold: Number 1: I have a plan; Number 2: Trust in Number 1. It’s the trust part that I find difficult. His broader answer is found in all of Sacred Scripture as a whole. The Biblical characters are believers who take upon themselves the plan of God. They all suffer. Many suffer a lot. Their very lives are our evidence that there is a divine plan.

God takes the suffering of humankind seriously and personally. When He took our form, He suffered in every way we do, including the humiliation of rejection to the point of crucifixion and death. Remember His trial before Pontius Pilate when “The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’.”

Like me, many of you have, at one time or another in your life, found yourself upon the dung heap of Job.

The Most Dangerous Thing in Prison

While writing this post, I stumbled upon a scene in a TV drama. I’m not sure which one it was, but the scene was in a prison. A rough looking character had spent 20 years in prison on death row for a crime he did not commit. A younger man was telling him that his friends on the outside want to take up the death row prisoner’s case. “Tell them to stop!” the older man said. “Please don’t give me hope. The most dangerous thing in prison is hope.”

No doubt, that statement was perplexing for most viewers, but I readily understood it. It recalled some dismal feelings from a time when hope emerged in prison only to be cruelly shattered. The shattering of hope often feels worse than no hope at all. That’s the danger the prisoner was talking about.

For me, the shattering of hope began on September 11, 2001. Early that year, Dorothy Rabinowitz, a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for The Wall Street Journal took an interest in my trial and imprisonment, and the evidence of fraud and misconduct behind them. For my part, gathering and photocopying documents from prison is a very difficult task, but over the course of that year, I labored to send reams of requested documentation to Ms. Rabinowitz. Then, just as the story grew into real interest, the forces of evil struck hard.

As you know well, the terrorist attacks of 9/11 destroyed the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in Manhattan. Their collapse damaged many of the surrounding buildings including the editorial offices of The Wall Street Journal on Liberty Street just across the World Trade Center Plaza.

Months passed while The Wall Street Journal relocated its offices to 1211 Avenue of the Americas. In early January 2002, a letter came from a member of the WSJ Editorial Board. All was lost. We had to start over. But I believed at the time that I could not start over. It seemed an overwhelming task. Hope was crushed along with the towers themselves.

The loss of thousands of lives added great weight to that sense of hopelessness. I could not possibly confront my personal loss in the face of so much human tragedy caused by so much human evil. I will never forget the nightmare I had after receiving that letter. I was inside World Trade Center Tower One when the first plane struck. It was collapsing all around me. The nightmare was long, real, and horrifying. At the end of the dream I was still alive, but regretfully so. I have never been a person who sees the world in terms of himself. I tried to convey that in a post about the horrors of that day, “The Despair of Towers Falling, The Courage of Men Rising.”

I just had to wait a bit before my own courage would rise again. By the time I recovered the resolve to start over in 2002, the Catholic clergy abuse scandal erupted in Boston just a few months after 9/11 to become another New England witch hunt that swept the nation. This made my hope, and The Wall Street Journal’s effort toward justice a much steeper climb. It has always struck me that the two stories — the hijacking of the planes that attacked Manhattan and the Pentagon on 9/11, and the collapse of the dignity and morale of Catholic priests — both began in my hometown of Boston just weeks apart.

Sorrow Needs a Panoramic View

I cannot tell you how to suffer. I do not even know how myself. I can only tell you that, along with most of you, I do suffer. Perhaps that means something as a starting point. Maybe those who know sorrow feel at some fundamental level that reflection on the experience from someone who also suffers means more than a smug and smiling Gospel of prosperity from some TV evangelist.

I don’t mean to pick on TV evangelists and God help me if I judge them harshly, but I have a hard time reconciling the trenches of suffering with the Gospel of prosperity that some of them proclaim. No one in prison listens to Joel Osteen. His word is for the brokers, not the broken; not the broken-hearted.

A sanitized TV version of grace and glory feels nothing but empty and shallow against the real deep sorrow of the trenches. I found myself in one of those trenches, and, like Job on his dung heap, I was dragged there kicking and screaming at God for its injustice. For a long time, I have wondered what I did to deserve this trashing of my freedom, my name, and worst of all, my priesthood. I do, after all, have a King other than Caesar!

So does Peggy Noonan. She was a White House speechwriter for President Ronald Reagan, and now she writes the “Declarations” column for The Wall Street Journal’s Weekend Edition. She is neck deep in the affairs of New York City and Washington, but she also has her finger on the pulse of that vast expanse of America that stretches from there to the Pacific.

Peggy Noonan’s January 27, 2018 column was entitled, “Who’s Afraid of Jordan Peterson?” Formerly associate professor of psychology at Harvard, Jordan Peterson has taught psychology at the University of Toronto for 20 years. Ms. Noonan wrote about a British TV report on his book, 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos.

She was intrigued because the interviewer was critical of Professor Peterson for his resistance to adopting the new orthodoxy of political correctness. Ms. Noonan summarized that the interviewer tried to silence his …

“… scholarly respect for the stories and insights into human behavior — into the meaning of things — in the Old and New Testaments. Their stories exist for a reason, he says, and have lasted for a reason: They are powerful indicators of reality, and their great figures point to pathways.”

Those Biblical pathways, it turns out, are always through the dark woods of sorrow. As I have written before, Sacred Scripture — the story of God and us — is filled with irony. The characters that populate the Biblical stories experience transformations born of suffering and sorrow.

Why we suffer is a cosmic mystery, but it is so even for God. As Saint Paul wrote, “He humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death, death on a cross” (Philippians 2:8). With trust, suffering takes on a meaning far greater than itself.

God Sees Facebook Too

If I were Job this is how I could frame my own lament:

“I spent the last 29 years in a dark periphery of my own called unjust imprisonment. Such a plight can cause a man to focus entirely on himself and his own bizarre fate. Those without hope here live in a prison inside a prison.”

I want to tell you about something that happened after I wrote a post entitled “Left Behind: In Prison for the Apocalypse.” It was about my friend, Skooter, who left this prison eleven years ago to face a life alone. Saint Mother Teresa once wrote that poverty does not mean just a lack of money, or food, or housing. The deepest poverty on Earth, she wrote, is to live life with no one who cares about us, no one to walk with us in suffering or sorrow.

I will always remember the day Skooter left us. From a distance, Pornchai Moontri and I watched him walk out the door carrying his life in two trash bags, but with no idea where, or to whom he would go. His life was missing the infrastructure that so many in Joel Osteen’s audience might take for granted.

Skooter was a young prisoner whom I taught to read and write. When he left prison, I never heard from him again except through a cryptic third party “thank you” from another young man who found himself back inside.

I did not know what happened to Skooter, nor did I know what exactly prompted me to write that post about him five years after he fell into silence. The silence was not his choice. When prisoners leave here, they are barred from contacting anyone left behind.

I do not know what prompted me to do this, but months after I wrote that post about him, I decided to try to find Skooter to see if he might like to read it. I called a friend, Charlene Duline in Indiana, a retired State Department official who became Pornchai Moontri’s Godmother in his Divine Mercy conversion. Charlene looked for Skooter on Facebook (using his given name), but the search yielded no result. A few days later, for reasons I do not know, I asked her to try again.

Now obviously, I have no access to Facebook but a past editor started a page for Beyond These Stone Walls. I have never even seen it so I don’t have a clue how Facebook works. I only know that my posts are shared there and that about 4,000 people “follow” them there. So while I was on the telephone with Charlene, she did the search again, but this time it yielded one result. I asked her to send a “connect request” from me. Within seconds, the acceptance came back with this message:

“G, is this really you? Is this possible?”

It seemed so bizarre that we were actually communicating in real time. Charlene sent Skooter a short reply telling him that she was on the telephone with me at that moment. Skooter sent back a number and asked me to call it. All the telephones in this prison are outside. So in the frigid cold, I called that number.

Skooter answered, and what he told me was astonishing. Skooter had been through a terrible dark night. After leaving prison at age 25, he struggled to build the life that he never had. He was alone, but he worked hard. Life was looking just a little promising and hopeful, then a cascade of dominoes began to fall.

Months before my sudden Facebook message reached Skooter, he lost his job. His boss in a small construction company was charged with some sort of corruption that Skooter had nothing to do with, but he was the collateral damage. Losing his job with no ability to plan was catastrophic. Paying rent by the week in substandard housing — a plight faced by so many former prisoners — Skooter then lost his place to live.

Everything he owned, which wasn’t much, ended up in storage. Then, unable to pay his storage bill, he lost even that. Living in a homeless shelter, Skooter went to a Christian food pantry for some help. He was asked for an address and he said he did not have one. He was told that he needs an address before they can give him food. Skooter roamed the streets and despaired.

Early in the morning after a sleepless night in the cold, he walked into the woods feeling totally defeated. He brought a rope. I’m sorry, but there is just no comfortable way to tell this. Skooter hanged himself from a tree. A hunter came upon the scene and cut down Skooter’s unconscious body, but he was still alive.

The hunter left Skooter on the ground and called the police from a highway rest area pay phone. Skooter was taken to a hospital where he had a 48-hour emergency commitment in the psychiatric ward. This is all dismal, but the rest shook me to the core. When Skooter emerged from this nightmare, he went to a city library to keep warm. He learned that he can use a computer there for free.

Feeling alone and discarded, the very poverty that Saint Mother Teresa described above, something compelled him to open a Facebook account. It was at that moment that I was on a phone from prison talking with Charlene when we searched for Skooter for the second time and there he was. Skooter told me that as he sat there wondering what to do next, my “friend request” appeared on his screen.

The photo of Skooter (above) was taken at a friend’s home at Christmas before his dark night brought him into a dark forest. I have been where Skooter was. I wrote of “How Father Benedict Groeschel Entered My Darkest Night.” Now I have entered Skooter’s darkest night, and from inside these prison walls I walk with him through his pathways of suffering and sorrow. No one could today convince Skooter that God has no plan.

So, where were you when God laid the foundations of the Earth? Have you ever in your life commanded the morning or showed the dawn its place?

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. You might like these other posts cited herein:

The James Webb Space Telescope and an Encore from Hubble

The Chief Priests Answered, ‘We Have No King but Caesar’

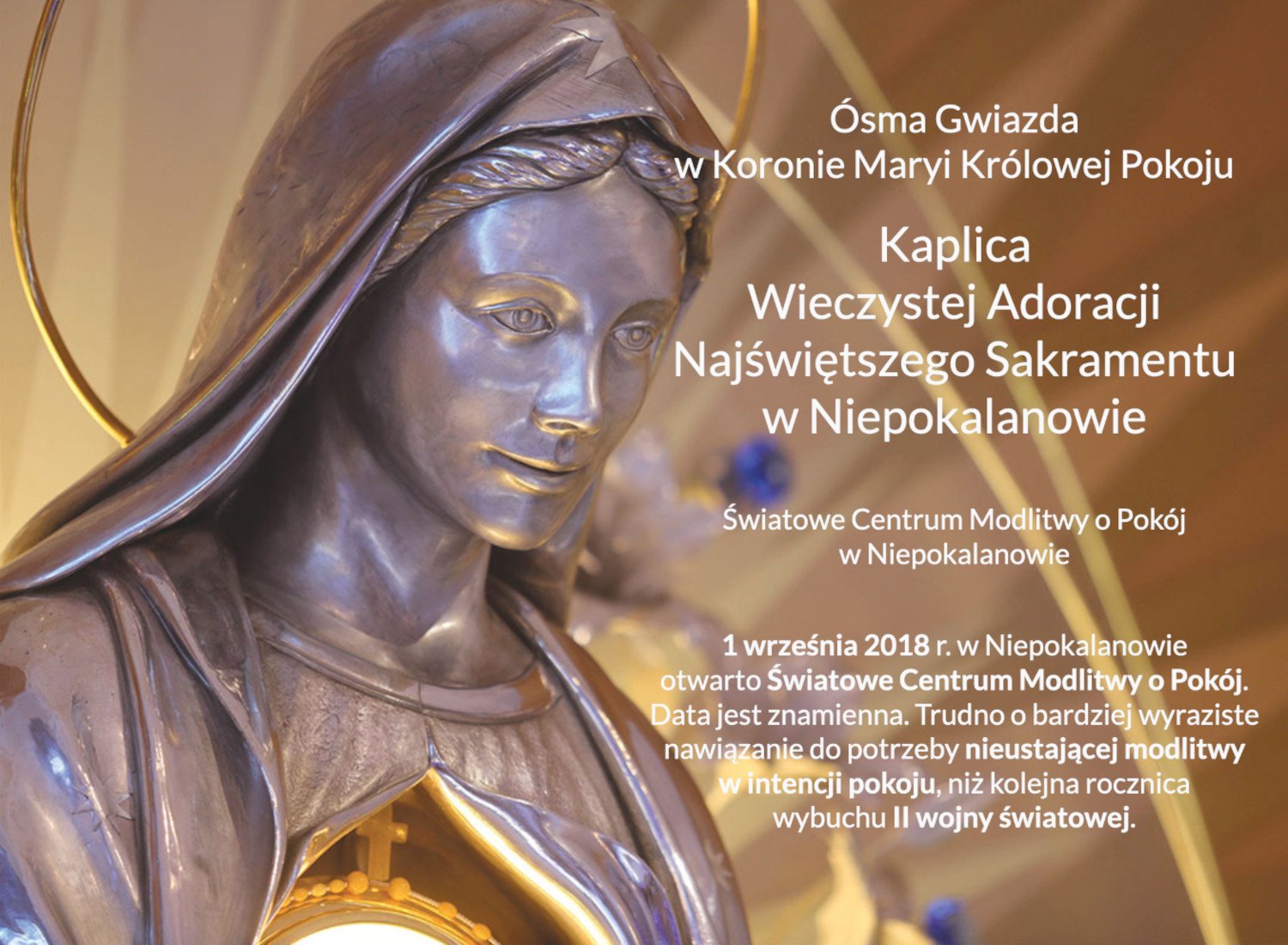

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”