“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Holidays in the Hoosegow: Thanksgiving with Some Not-So-Just Desserts!

Thanksgiving is a state of mind, not place. Even prisoners can be thankful, if not for being prisoners, then perhaps just for the art of being itself.

Thanksgiving is a state of mind, not place. Even prisoners can be thankful, if not for being prisoners, then perhaps just for the art of being itself.

November 12, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

I have been hindered from writing a new post this month. This gets a little creepy, so bear with me. On the night of October 31, I was visited in my cell by two brown recluse spiders who were apparently hiding in a shirt that I put on that night because I was cold. Well, so were the spiders and unbeknownst to me they claimed squaters rights to the shirt. Sometime during the night leading to the Solemnity of All Saints, I was bitten twice in the back by two poisonous spiders.

It was a few days before I sought treatment being the stubbornly independent person that I am. Finally the bites evolved into a serious blood infection that now requires all-out war. I now have daily visits to the Medical Unit for wound treatment and new bandaging. I am also on a potent antibiotic. There is some tissue damage. I lost the battle with the spiders, but I am told that I am winning the war thanks to the medical care I am receiving.

The worst part of this whole story was when I told it in a phone call to Pornchai Max Moontri in Thailand, he launched into singing “Itsy, Bitsy Spider.”

+ + +

I hope you will read “The True Story of Thanksgiving” posted here every year in late November, this year included. I figure that, in America at least, we eat the same meal every year at Thanksgiving. It is a holiday bound up in traditions. Every year I grimace as the U.S. President pardons a turkey on national television, then gobbles up an already preplucked Butterball in its place for Thanksgiving Dinner. So we added a tradition of our own several years ago, which you will find repeated again this year on the day before Thanksgiving.

Even The Wall Street Journal honors its own Thanksgiving tradition by repeating, on the day before Thanksgiving, the same two editorials at the top of its opinion page. So the message is that repetition is not a bad thing and the story we tell at Thanksgiving is both historically true and spiritually wondrous. Since I first wrote it back in 2010, references to it have appeared in two published history books about the Mayflower Pilgrims. We expect to publish it anew here on Wednesday, November 26.

I hope you will plan to read “The True Story of Thanksgiving: Squanto, the Pilgrims, and the Pope.”

Thanksgiving is a tough sell for most prisoners. It often involves only a litany of losses and discouragement. But I have advocated among other prisoners a more positive approach with some mixed success.

I am not quite ready to give thanks just yet for my 31st Thanksgiving holiday in the hoosegow. But writing this post did make me wonder about the origin of “hoosegow.” The local cable system here carries American Movie Classics (AMC) which broadcasts old westerns on most Saturday mornings. I love John Wayne movies, especially the later ones. It might have been in one of those that I heard Walter Brennan (who, by the way, is from my hometown!) playing a cranky old deputy sheriff.

I can even now hear Walter Brennan threatening to throw someone in the “hoosegow.” Hoosegow has an interesting origin. It comes from the phonetic pronunciation of a Spanish word, “Juzgado,” meaning “courtroom.” It is the past participle of “juzgar,” which in turn came from the Latin “iudicare,” (pronounced, “you-dee-CAR-eh) meaning “judge.” Since judges send people to jail, “juzgado” came to refer to jails and prisons. Then, in the slang of border towns in the American Old West, it became “hoosegow.” So now you know the origin of the word, hoosegow. Don’t thank me just yet!

Here in the hoosegow, like everywhere else in the U.S., we are about to mark Thanksgiving. I would not use “celebrate” to describe how prisoners observe this, or any, holiday. On the whole, prisoners do not really celebrate much. But even here most can find something to be thankful for. I found such a moment several years ago when Pornchai Max and other friends were still here with me. I will even go so far as to say I celebrated it.

The Earth’s journey around our Sun brings about the inevitable changing seasons beyond these stone walls. I have journeyed in life 72 times around our Sun, but most of the fallen citizens around me barely notice the changing world. We venture outside each day among asphalt and steel and high concrete walls with little evidence of the march of time and the changing seasons. The “Field of Dreams” — the prison ball field and the one place with trees in sight — closed for the year two months ago. The only leaves I see now are the very few that the wind carries over the high prison walls which consume my view of the outside world.

One day in autumn some years ago, I turned a corner outside on the long, concrete ramp winding its way up to the prison mess halls. I looked up to discover a spot I never noticed before.

It was a place amid the concrete and steel that afforded a momentary glimpse of a tree-covered hill in the distance beyond the walls, and the rays of the setting sun had fallen upon that very spot. For a moment, the hill was clothed in a blaze of glory with an explosion of fall color. It was magnificent! I felt a bit like Dorothy Gale, stepping for the first time out of the gray gloom of her Kansas home into the startling glory of the Land of Oz.

Prisoners are not permitted to stop and gawk while moving from Point A to Point B, but in two more steps, or a few more seconds, the view would be gone. So I nudged Pornchai and Joseph who were walking with me, and we all stared for a moment in awe. We froze in our tracks for those seconds, risking a guttural shout of “KEEP MOVING!” from one of the guards posted along this via dolorosa.

There was a guard right at that spot, poised to bellow, but then he followed our gaze and he, too, gawked for a moment, keeping his shout to himself. We moved on up the ramp amid all the downcast eyes around us, but saw no evidence that anyone else noticed that scene of radiant beauty beyond these stone walls. I thanked God in silence for nudging me to look up just then. It was proof that a moment for giving thanks presents itself every day, even in this awful place. Those moments will be passed by unnoticed if I am so consumed with grief that I fail to look up and out beyond these stone walls. I have to look up to see. I have to keep my eyes opened, and focus somewhere beyond just me.

I look up at that spot every day now, but the color has faded to a barren gloom, just like life here — or anywhere else — can if I let it. I have learned from Squanto of The Dawn Land that even the worst plight affords an opportunity for thanksgiving. We must not let those moments pass by unnoticed for our very souls depend on them.

I despise this place of captivity where so many of the days given to me have been spent. Really spent! Yet on past Thanksgiving Days, Pornchai, and Joseph, and other friends who walked with us each day, all found a few seats together in the prison chow hall. There we gave thanks for turkey, for an annual piece of pumpkin pie, for friendship found even in the ruins of lives broken and dreams delayed, for laughter in the face of pain, and especially for the gift of bearing one another’s burdens with thanks for the graces given to us.

In a sea of downcast eyes, furtive glances, and foul speech seldom rising above talk of gangs, and drugs, and the exploitation of others, Pornchai showed off his Saint Maximilian medal, and spoke of salvation and sacrifice and the privilege of being Catholic in a truly destitute public square.

In the end, I had been left with no choice and no other prayer to utter: Thank you, Lord, for this day!

+ + +

Note from the BTSW Editor: There are simple ways in which you may help magnify this Voice in the Wilderness.

It helps much to subscribe to Father Gordon’s posts. Note that you will receive an email asking you to confirm your subscription.

Though we have given up sharing Father Gordon’s posts on Facebook, Pornchai Maximilian Moontri has a Facebook Page in Thailand, which he uses to share our posts in Southeast Asia communities. You may send your “Friend Requests” to Pornchai Maximilian Moontri.

It would also help Father Gordon substantially if you follow him on X, formerly Twitter.

Both Father Gordon and Pornchai Moontri have a strong following at LinkedIn.

And lastly, Father Gordon’s page at gloria.tv is always worth a visit.

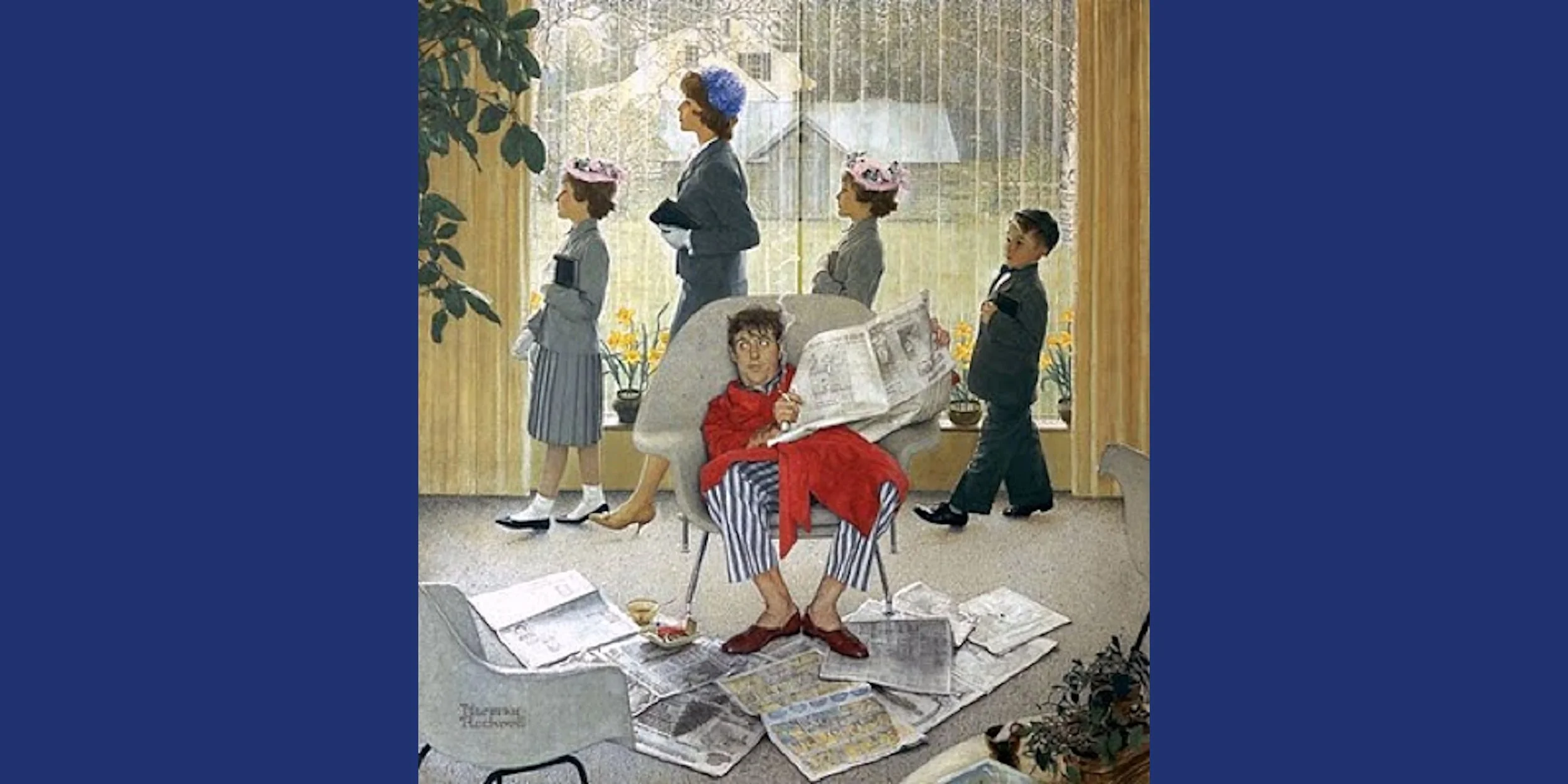

John Wayne and Walter Brennan in Rio Bravo.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

What do John Wayne and Pornchai Moontri Have In Common?

Pornchai Moontri celebrates his 52nd birthday on September 10 this year. It is his 15th birthday as a Catholic, a conversion he shares with the great actor, John Wayne.

Pornchai Moontri celebrates his 52nd birthday on September 10 this year. It is his 15th birthday as a Catholic, a conversion he shares with the great actor, John Wayne.

September 10, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

I last wrote about our friend and my former roommate, Pornchai Max Moontri at a time of tragedy. That post was “A Devastating Earthquake Shook Thailand, Myanmar and Our Friends.” Ironically, I just noticed, it appeared on April 9, 2025, which was my 72nd birthday. I was recently talking with Pornchai in Thailand by telephone, and the subject of birthdays came up. He was absent from Thailand for 36 years, and it was 36 years of loss and tragedy. He spoke of his impression that what constitutes “family” for him is not only those with whom you share blood, but even more so those with whom you share and survive trials and tribulation. This is why those in the military who go through war together and survive form a bond that transcends all other bonds, including family. I readily agreed with that and mentioned the famous series, Band of Brothers as an example.

In an earlier post, “February Tales and a Corporal Work of Mercy in Thailand,” I described growing up on the Massachusetts North Shore — the stretch of seacoast just north of Boston. My family had a long tradition of being “Sacrament Catholics.”

I once heard my father joke that he would enter a church only twice in his lifetime, and would be carried both times. I was seven years old, squirming into a hand-me-down white suit for my First Communion when I first heard that excuse for staying home. I didn’t catch on right away that my father was referring to his Baptism and his funeral. I pictured him, a very large man, slung over my mother’s shoulder on his way into church for Sunday Mass, and I laughed.

We were the most nominal of Catholics. Prior to my First Communion at age seven, I was last in a Catholic church at age five for the priesthood ordination of my uncle, the late Father George W. MacRae, a Jesuit and renowned Scripture scholar. My father and “Uncle Winsor,” as we called him, were brothers — just two years apart in age but light years apart in their experience of faith. I was often bewildered, as a boy, at this vast difference between the two brothers.

But my father’s blustering about his abstention from faith eventually collapsed under the weight of his own cross. It was a cross that was partly borne by me as well, and carried in equal measure by every member of my family. By the time I was ten — at the very start of that decade of social upheaval, life in our home had disintegrated. My father’s alcoholism raged beyond control, nearly destroying him and the very bonds of our family. We became children of the city streets as home and family faded away.

I have no doubt that many readers can relate to the story of a home torn asunder by alcoholism, and some day I hope to write more about this cross. But for now I want to write about conversion, so I’ll skip ahead.

The Long and Winding Road Home

As a young teenager, I had a friend whose family attended a small Methodist church. I stayed with them from time to time. They knew I was estranged from my Catholic faith and Church, so one Sunday morning they invited me to theirs. As I sat through the Methodist service, I just felt empty inside. There was something crucial missing. So a week later, I attended Catholic Mass — secretly and alone — with a sense that I was making up for some vague betrayal. At some point sitting in this Mass alone at age 15 in 1968, I discovered that I was home.

My father wasn’t far behind me. Two years later, when just about everyone we knew had given up any hope for him, my father underwent a radical conversion that changed his very core. He admitted himself to a treatment program, climbed the steep and arduous mountain of recovery, and became our father again after a long, turbulent absence. A high school dropout and machine shop laborer, my father’s transformation was miraculous. He went back to school, completed a college degree, earned a masters degree in social work, and became instrumental in transforming the lives of many other broken men. He also embraced his Catholic faith with love and devotion, and it embraced him in return. That, of course, is all a much longer story for another day.

My father died suddenly at the age of 52 just a few months after my ordination to priesthood in 1982. I remember lying prostrate on the floor before the altar during the Litany of the Saints at my ordination as I described in “The Power and the Glory if the Heart of a Priest Grows Cold.” I was conscious that my father stood on the aisle just a few feet away, and I was struck by the nature of the man whose impact on my life had so miraculously changed. Underneath the millstones of addiction and despair that once plagued him was a singular power that trumped all. It was the sheer courage necessary to be open to the grace of conversion and radical change. The most formative years of my young adulthood and priesthood were spent as a witness to the immensity of that courage. In time, I grew far less scarred by my father’s road to perdition, and far more inspired by his arduous and dogged pursuit of the road back. I have seen other such miracles, and learned long ago to never give up hope for another human being.

The Conversion of the Duke

I once wrote that John Wayne is one of my life-long movie heroes and a man I have long admired. But all that I really ever knew of him was through the roles he played in great westerns like “The Searchers,” “The Comancheros,” “Rio Bravo,” and my all-time favorite historical war epic, “The Longest Day.”

In his lifetime, John Wayne was awarded three Oscars and the Congressional Gold Medal. After his death from cancer in 1979, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But, for me, the most monumental and courageous of all of John Wayne’s achievements was his 1978 conversion to the Catholic faith.

Not many in Hollywood escape the life it promotes, and John Wayne was no exception. The best part of this story is that it was first told by Father Matthew Muñoz, a priest of the Diocese of Orange, California, and John Wayne’s grandson.

Early in his film career in 1933, John Wayne married Josephine Saenz, a devout Catholic who had an enormous influence on his life. They gave birth to four children, the youngest of whom, Melinda, was the mother of Father Matthew Muñoz. John Wayne and Josephine Saenz civilly divorced in 1945 as Hollywood absorbed more and more of the life and values of its denizens.

But Josephine never ceased to pray for John Wayne and his conversion, and she never married again until after his death. In 1978, a year before John Wayne died, her prayer was answered and he was received into the Catholic Church. His conversion came late in his life, but John Wayne stood before Hollywood and declared that the secular Hollywood portrayal of the Catholic Church and faith is a lie, and the truth is to be found in conversion.

That conversion had many repercussions. Not least among them was the depth to which it inspired John Wayne’s 14-year old grandson, Matthew, who today presents the story of his grandfather’s conversion as one of the proudest events of his life and the beginning of his vocation as a priest.

If John Wayne had lived to see what his conversion inspired, I imagine that he, too, would have stood on the aisle, a monument to the courage of conversion, as Matthew lay prostrate on the Cathedral floor praying the Litany of the Saints at priesthood ordination. The courage of conversion is John Wayne’s most enduring legacy.

Pornchai Moontri Takes a Road Less Traveled

The Japanese Catholic novelist, Shusaku Endo, wrote a novel entitled Silence (Monumenta Nipponica, 1969), a devastating historical account of the cost of discipleship. It is a story of 17th Century Catholic priests who faced torture and torment for spreading the Gospel in Japan. The great Catholic writer, Graham Greene, wrote that Silence is “in my opinion, one of the finest novels of our time.”

Silence is the story of Father Sebastian Rodriguez, one of those priests, and the story is told through a series of his letters. Perhaps the most troubling part of the book was the courage of Father Rodriguez, a courage difficult to relate to in our world. Because of the fear of capture and torture, and the martyrdom of every priest who went before him, Father Rodriguez had to arrive in Japan for the first time by rowing a small boat alone in the pitch blackness of night from the comfort and safety of a Spanish ship to an isolated Japanese beach in 1638 — just 18 years after the Puritan Pilgrims landed the Mayflower at Squanto’s Pawtuxet, half a world away as I describe in “The True Story of Thanksgiving.”

In Japan, however, Father Rodriguez was a pilgrim alone. Choosing to be left on a Japanese beach in the middle of the night, he had no idea where he was, where he would go, or how he would survive. He had only the clothes on his back, and a small traveler’s pouch containing food for a day. I cannot fathom such courage. I don’t know that I could match it if it came down to it.

But I witness it every single day. Most of our readers are very familiar with “Pornchai’s Story,” and with his conversion to Catholicism on Divine Mercy Sunday in 2010. Most know the struggles and special challenges he has faced as I wrote in “Pornchai Moontri, Bangkok to Bangor, Survivor of the Night.”

But the greatest challenge of Pornchai’s life was yet to come. After serving more than half his life in prison in a sentence imposed when he was a teenager, Pornchai faced forced deportation from the United States to his native Thailand. Like Father Sebastian Rodriguez in Silence, Pornchai would be stepping onto the shores of a foreign land in darkness, a land he no longer knew and in which he knew no one.

This was a time of great turmoil for both of us. I have told much of this story before, but it is worth repeating now. I asked Pornchai to write his life story. He was lost for words and did not know how or where to begin. So I asked him to just talk. He sat on the floor of our prison cell and the words came cautiously at first, but then they began to flow as I took notes. Neither of us knew what to expect but in the end I typed the four pages from my notes and titled it simply “Pornchai’s Story.” We had no way to know that this short story would become known all over the world. I sent a copy to Catholic League President Bill Donohue, a Catholic leader with a heart of pure gold. Dr. Donohue published it on the Catholic League website and he wrote that it was “remarkable.” Then the letters came addressed to Pornchai. One was from Ambassador Mary Ann Glendon, who was then U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See. Another was from the late Father Richard John Neuhaus, Editor of First Things magazine, who told Pornchai that his powerful story would turn many souls back to God. Yet another was from Cardinal Kitbunchu, the Archbishop Emeritus of Bangkok. Yet another was from Yela Roongruangchai, Founder and President of Divine Mercy Thailand.

Also in Thailand at the time “Pornchai’s Story” arrived was Father Seraphim Michalenko, MIC, who also happened to be the Vatican’s Postulator for the Cause of Sainthood of Saint Maria Faustina Kowalska, the Saint of Divine Mercy. Father Seraphim read “Pornchai’s Story” aloud during a Divine Mercy Retreat in Bangkok. Ten years before all of this happened, I boldly told Pornchai during a night of near despair, that we would have to build a bridge from a prison in Concord, New Hampshire to Thailand. Pornchai scoffed, but it was the only hope we had to hold onto. Then the bridge was built right before our very eyes. What we once faced with terror in the darkness of a future unseen, we now face with the gift of hope. Happy Birthday, Max!

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Don’t stop here. Learn a bit more of this story through the following related posts:

Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom

The Shawshank Redemption and Its Grace Rebounding

Thailand’s Once-Lost Son Was Flag Bearer for the Asian Apostolic Congress

A Catholic League White House Plea Set Pornchai Moontri Free

+ + +

A Further Note from Father Gordon MacRae: While writing the above post I received a note from my friend Sheryl Collmer in Tyler, Texas. Along with it was an article Sheryl had written for Crisis Magazine. The article is about the magnificent new film, Triumph of the Heart, telling the story of our Patron Saint Maximilian Kolbe. Sheryl’s article is magnificent in its own right and it casts a light into a very dark place in our world. But her article does not leave us there. There is not much in this world that makes me want to shout from the rooftops, but Sheryl Collmer’s article is one of them. You must not miss “The Tenebrae of Maximilian Kolbe” and I hope you will share it.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Simon of Cyrene Compelled to Carry the Cross

Simon of Cyrene was just a man coming in from the country to Jerusalem for the Passover when his fated path intersected the Way of the Cross and Salvation History.

Simon of Cyrene was just a man coming in from the country to Jerusalem for the Passover when his fated path intersected the Way of the Cross and Salvation History.

Holy Week 2023 by Fr. Gordon MacRae

I first wrote about Simon of Cyrene in Holy Week, 2010. While restoring that post, I ended up completely rewriting it. It led me almost immediately to a vivid example of the descent of this world at a time when faith invites us to ascend to Eternal Life. We are all going to die. It is an ordinary part of life. But don’t just die. Set out now for home. The only true path to life leads “To the Kingdom of Heaven through a Narrow Gate.”

A single sentence about Simon of Cyrene in each of the Synoptic Gospels conveys a wealth of meaning with a roadmap to the way home. Several readers told me privately and in comments that they were struck by these last few sentences in a recent post that mentioned Pornchai Moontri. In “God in the Dock: When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” I wrote,

“It was upon reading [a] passage from Pope Benedict that Pornchai made his decision to journey with me from the Exodus, through the desert, to the Promised Land toward which we, in hope, are destined. Faith never rescued us from our trials, but it taught us to carry one another's cross like Simon of Cyrene. That is the key to Heaven. Even in suffering and sorrow, it is the key to Heaven.”

Under the weight of Earthly Powers, this world loses sight of our true destiny while the great masses of people focus only on what they have stored up in this life. When a bank fails those whose treasury contains little more than money in life, people panic, some even commit suicide. It's a tragedy unfolding before our very eyes in the weeks leading up to Holy Week.

I turn 70 years old on Easter Sunday this year. It haunts me to reflect on how much the values of this world have changed in my lifetime. While researching this post about Simon of Cyrene, I came across a reference to The Greatest Story Ever Told, a 1960 United Artists film production of the life of Jesus from his birth to his Resurrection. Today, many of the woke denizens of Hollywood might shun such a project, but in 1960 it drew an enormous cast of Hollywood stars clamoring to be part of 'it.

Some of the film industry's most stellar actors were cast, some surprisingly in even minor roles: Max von Sydow portrayed Jesus, Dorothy McGuire was Mary, Claude Rains was Herod the Great, Jose Ferrer was Herod Antipas, Charlton Heston was John the Baptist, Telly Savalas was Pontius Pilate. He shaved his head for the role and never grew his hair back again. This is why he was bald when he played the famous NYPD detective, Kojak. David McCallum was Judas Iscariot. The list of Hollywood stars goes on and on.

The great John Wayne was cast as a captain of the Roman Centurions who professed his belief in Jesus at the foot of the Cross, as depicted in the top graphic on this post. John Wayne became a Catholic not long after this film. Today, his grandson is a Catholic priest in California.

Simon of Cyrene was portrayed by Sidney Poitier who three years later won an Academy Award for his portrayal of a drifter who became a handyman for a community of nuns in Lillies of the Field. He was an interesting choice to play Simon of Cyrene. In New Testament times, Cyrene was a major city in Northern Africa with a large Jewish population in what is present day Libya. It was the home of Lucius, a prophet and teacher of Antioch mentioned in Acts 13:1, and of Simon, a man who ventured to Jerusalem for the Passover but found himself in the wrong place at the wrong time or, depending on your perspective, in the right place at the right time.

Weep Not for Me, Jerusalem

My first inkling to learn about Simon of Cyrene was during Holy Week in 2000, nine years before this blog began. An old friend planning a visit to the Holy Land asked me to write a prayer that he promised to leave in a crevasse in the famous Western Wall. Known popularly as the “Wailing Wall,” it was built by Herod the Great (who was not so great, really!). That section of wall was all that remained standing after the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by the Romans in 70 AD. Known in Hebrew as “ha-Kotel ha-Maaravi,” it is today one of the holiest pilgrimage sites in the Holy Land.

According to the Midrash, a collection of ancient rabbinic scholarship, the Wall survived the destruction of the Temple because the Shekhinah, the Divine Presence, rests there. My friend left my handwritten prayer in a crevasse in that Wall. Just a day later, during a historic pilgrimage to the Holy Land, Pope John Paul II left his own prayer in that same place in the Wall. I recall hoping that his was not blocking mine!

On that same day, just beyond the city walls, my friend came upon a tourist area where a photographer was capitalizing on the presence of the Pope. He tried to coax my friend into picking up a mock cross and carrying it for a photograph. My friend was appalled by the disconnect between what happened at Calvary 2000 years earlier and what was happening in that present scene. He refused to pick up the cross.

Reflecting on the scene upon his return from Jerusalem, my friend wrote to me in prison asking, “What can you tell me about Simon of Cyrene?” His question took me to a single sentence in each of the Synoptic Gospels from which I felt compelled to unpack some hidden meaning. It turned out that there was much to unpack.

Jesus, denounced by the Chief Priests, tried and condemned before Pilate, was mercilessly scourged to the point of near death. Roman soldiers tasked with his crucifixion feared that he may die before the ascent of Golgotha while bearing history's heaviest cross. Roman law allowed soldiers to press Jews into service for Rome so they forced a passerby to assist the “King of the Jews” as recounted in all three of the Synoptic Gospels:

“As they went out, they came upon a man of Cyrene, Simon by name; this man they compelled to carry the cross.”

— Matthew 27:32

“And as they led [Jesus] away, they seized one Simon of Cyrene, who was coming in from the country, and laid on him the cross to carry it behind Jesus.”

— Luke 23:26

“And they compelled a passer-by, Simon of Cyrene who was coming in from the country, the father of Alexander and Rufus, to carry his cross.”

— Mark 15:21

Sidney Poitier as Simon of Cyrene in The Greatest Story Ever Told

He Was There When They Crucified My Lord

Crucifixion was entirely unknown in Jewish history until the Roman occupation of Palestine in 31 BC. Sacred Scripture, however, contained echoes of the sacrifice to come. Some 2,000 years before Jesus ascended Calvary bearing his Cross, Abraham was summoned by God to sacrifice his son, Isaac in the land of Moriah (Genesis 22).

Israelite tradition (2 Chronicles 3:1) identifies Moriah as the site of the future Jerusalem Temple. What became Golgotha or Calvary was one of its foothills. Obedient but brokenhearted, Abraham placed upon his son the wood for his sacrifice and together they climbed Mount Moriah.

Isaac asked his father, “Where is the lamb for the sacrifice?” Abraham answered, “God will provide himself the lamb for the offering, my son” (Genesis 22:8). In the end, an Angel of the Lord stayed Abraham’s hand, and his obedience became the basis for God’s covenant with Israel. Two millennia later, in that same place, God Himself did provide the lamb for the sacrifice. Hence, in our Liturgy, Jesus is the “Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.”

Crucifixion was a common form of capital punishment among Persians, Egyptians, and Romans from the 6th century BC to the 4th century AD. The punishment was ritualized under Roman law which required that a criminal be scourged before execution. The accused had to carry the entire cross or just the crossbeam from the place of scourging to the execution. Crucifixion was abolished in 337 AD by Emperor Constantine out of respect for the emergence of Christianity in the Roman Empire. Jews carried out their own form of capital punishment by stoning, but the Romans forbade such executions when they occupied Palestine. This is why Jesus was handed over to Pilate for trial.

The gruesome punishment of crucifixion was reserved by the Romans for criminals, seditionists, and slaves. Roman law forbade the crucifixion of a citizen for any crime. Saint Paul, who was a Roman citizen, could not be crucified so he was martyred by Emperor Tertullian, likely by beheading, in 60 A.D.

When Pilate had Jesus scourged, he may have instructed his tormentors to go beyond the usual torture hoping to convince the Sanhedrin and the mob that scourging was punishment enough. That plan failed when the crowd, spurred on by the Chief Priests, shouted “Crucify Him!”

However Jesus had been beaten so severely that Roman soldiers doubted that he could carry his cross the entire distance to Calvary alone. Note that I use the terms “Golgotha” and “Calvary” interchangeably. They are one and the same place. Golgotha is a Greek translation from an Aramaic word meaning “Place of the Skull,” a name likely derived from the fact that many executions were carried out there. “Calvary” is derived from “calvaria,” the Latin translation of Golgotha.

A condemned man was then led through the crowds to the place of crucifixion. Just as today, most of the people in the crowds assumed that an all-powerful and righteous state has justly condemned a real criminal to punishment, so many joined in the mocking and humiliation even if they knew nothing of the accused or the alleged crime. It was part of the ritual. Along the way, the condemned was forced to carry his cross — or at least the crossbeam upon which his arms would be tied and his hands or wrists nailed (see John l9:l7).

In 1994, the year I was sent to prison, archeological remains of a crucified man were discovered intact near Jerusalem. It was the first evidence of what actually took place in a typical Roman crucifixion.

It is unclear from the Gospel passages above exactly what part of the Cross was imposed upon Simon of Cyrene. Luke’s Gospel refers to Simon carrying the Cross behind Jesus, a position which also came to be symbolic of discipleship. It is likely that Jesus, like other condemned, carried the crossbeam upon which he would be nailed, while Simon may have carried the vertical beam or the rear of the entire Cross.

I learned from Mel Gibson’s famous film, The Passion of the Christ, that Simon of Cyrene is the person in the Gospel to whom I can most relate. I did not pick my cross willingly, nor do I willingly carry it. I did not see it as a share in the Cross of Christ at first. Few of us ever do.

The Passion of the Christ portrayed with power what I have always imagined must have become of Simon of Cyrene. Something stirred within him compelling him to remain there. He became a part of the scene, setting his own journey aside. The lights went on in Simon’s soul and he became compelled not just from Roman force, but from deep within himself.

Note that Saint Mark alone mentions that Simon of Cyrene had two sons, Alexander and Rufus. The Gospel implies that both became well known to the early Church. Being the earliest of the Gospels to come into written form, Mark addressed his Gospel to Gentile Christians in Rome. So did Saint Paul in his Letter to the Romans. Mark was with Paul at the time he was imprisoned in Rome so he was likely aware of Simon’s profound transformation as a witness to the Crucifixion and Saint Paul’s knowledge of his sons, Rufus and Alexander cited in Saint Mark’s Gospel.

Hence in the concluding verses of Paul’s Letter to the Romans Paul wrote: “Greet Rufus, eminent in the Lord, and also his mother who is a mother to me as well” (Romans 16:13).

+ + +

Note from Fr. Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and sharing this post which is now on our list of Holy Week posts for our sponsored Holy Week Retreat. It is not too late to follow the Way of the Cross this week by pondering and sharing our

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap the image for live access to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”