“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Twilight of Fatherhood: Cry, the Beloved Country

Fatherhood fades from the landscape of the human heart to the peril of the souls of our youth. For some young men in prison, absent fathers conjure empty dreams.

Fatherhood fades from the landscape of the human heart to the peril of the souls of our youth. For some young men in prison, absent fathers conjure empty dreams.

June 12, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

“Cry, the beloved country, for the unborn child that is the inheritor of our fear. Let him not love the earth too deeply. Let him not laugh too gladly when the water runs through his fingers, nor stand too silent when the setting sun makes red the veld with fire. Let him not be too moved when the birds of his land are singing, nor give too much of his heart to a mountain or a valley. For fear will rob him of all if he gives too much.”

— Alan Paton, Cry, the Beloved Country, 1948

I was five days shy of turning fifteen years old and looking forward to wrapping up the tenth grade at Lynn English High School just north of Boston on April 4, 1968. That was the day Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered in Memphis, Tennessee. On that awful day, the Civil Rights struggle in America took to the streets. History eventually defined its heroes and its villains.

There is an unexpected freedom in being who and where I am. I can write the truth without the usual automatic constraints about what it might cost me. There is only one thing left to take from me, and these days the clamor to take it seems to have abated. That one thing is priesthood which — in this setting, at least — places me in the supporting cast of a heart-wrenching drama.

But first, back to 1968. Martin Luther King’s “I Had a Dream” speech still resonated in my 14-year-old soul when his death added momentum to America’s moral compass spinning out of control. I had no idea how ironic that one line from Martin’s famous speech would be for me in years to come: “From the prodigious hills of New Hampshire, Let Freedom Ring!”

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, fourteen years to the day before I would be ordained a priest, former Attorney General and Civil Rights champion, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, was murdered in Los Angeles after winning the California primary. The Democratic National Convention in Chicago that August was marked by calamitous riots as Vice President Hubert Humphrey became the nominee only to lose the 1968 election to Richard Nixon in November.

Cry, the Beloved Country

It was at that moment in history — between the murders of two civil rights giants, one black and one white — that a tenth grade English teacher in a racially troubled inner city high school imposed his final assignment to end the school year. It was a book and a book report on Alan Paton’s masterpiece novel set in South Africa during Apartheid. It was Cry, the Beloved Country.

In a snail mail letter some months ago, a reader asked me to write about the origins of my vocation. His request had an odd twist. He wanted me to write of my call to priesthood in light of where it has put me, “so that we might have hope when God calls ordinary people to extraordinarily painful things.” I recently tried to oblige that request when I wrote “The Power and the Glory If the Heart of a Priest Grows Cold.”

I gave no thought to priesthood in the turmoil of a 1968 adolescence. Up to that time I gave little thought to the Catholic faith into which I was born. At age 15, like many adolescents today if left to their own devices, my mind was somewhere else. We were Christmas and Easter Catholics. I think the only thing that kept my family from atheism was the fact that there just weren’t enough holidays.

My first independent practice of any faith came at age 15 just after reading Cry, the Beloved Country. It started as an act of adolescent rebellion. My estranged father was deeply offended that I went to Mass on a day that wasn’t Christmas or Easter, and my decision to continue going was fueled in part by his umbrage.

But there was also something about this book that compelled me to explore what it means to have faith. Written by Alan Paton in 1948, Cry, the Beloved Country was set in South Africa against the backdrop of Apartheid. I read it in 1968 as the American Civil Rights movement was testing the glue that binds a nation. That was 56 years ago, yet I still remember every facet of it, for it awakened in me not just a sense of the folly of racial injustice, but also the powerful role of fatherhood in our lives. It is the deeply moving story of Zulu pastor, Stephen Kumalo, a black Anglican priest driven to leave the calm of his rural parish on a quest in search of his missing young adult son, Absalom, in the city of Johannesburg.

South Africa during Apartheid is itself a character in the book. The city, Johannesburg, represents the lure of the streets as a looming cultural detriment to fatherhood, family, faith and tradition. Fifty-six years after reading it, some of its lines are still committed to memory:

“All roads lead to Johannesburg. If you are white or if you are black, they lead to Johannesburg. If the crops fail, there is work in Johannesburg. If there are taxes to be paid, there is work in Johannesburg. If the farm is too small to be divided further, some must go to Johannesburg. If there is a child to be born that must be delivered in secret, it can be delivered in Johannesburg.”

— Cry, the Beloved Country, p. 83

Apartheid was a system of racial segregation marked by the political and social dominance of the white European minority in South Africa. Though it was widely practiced and accepted, Apartheid was formally institutionalized in 1948 when it became a slogan of the Afrikaner National Party in the same year that Alan Paton wrote his influential novel.

Nelson Mandela, the famous African National Congress activist, was 30 when the book was published. I wonder how much it inspired his stand against Apartheid that condemned him to life in prison at age 46 in 1964 South Africa. His prison became a symbol that brought global attention to the struggle against Apartheid which finally collapsed in 1991. After 26 years in prison, Nelson Mandela shared the Nobel Peace Prize with South African President F.W. de Klerk in 1993. A year later, Nelson Mandela was elected president in South Africa’s first fully democratic elections.

In the Absence of Fathers

I never knew my teacher’s purpose for assigning Cry, the Beloved Country at that particular moment in living history, but I have always assumed that it was to instill in us an appreciation for the struggle for civil rights and racial justice. I never really needed much convincing on the right path on those fronts, but the book had another, more powerful impact that seemed unintended.

That impact was the necessity of strong and present fathers who are up to the sacrifices required of them, and especially so in the times that try men’s souls. There is a reason why I bring this book up now, 56 years after reading it. I had a friend here in this prison who had been quietly standing in the background. I will not name him because there are people on two continents who know of him. He is African-American in the truest sense, a naturalized American citizen brought to this country when his Christian family fled Islamic oppression in their African nation. He was 20 years old when we met, and had been estranged from his father who was the ordained pastor of a small Evangelical congregation in a city not so far from our prison.

I came to know this young prisoner when he was moved to the place where I live. He disliked the new neighborhood immensely at first, finding little in the way of common ground, but Pornchai Moontri and his friends managed to draw him in. Perhaps what finally won him over was the fact that we, too, were in a strange land here. Pornchai brought him to me and introduced me as “everyone’s father here.”

We recruited him on Porchai’s championship baseball team which won the 2016 pennant defeating eight other teams.

I broke the ice one day when I showed our new friend a copy of a weekly traffic report for this blog. He was surprised to see a significant number of visits from the land of his birth. Our friend’s African name was hardly pronounceable, but many younger prisoners have “street names.” So after some trust grew a little between us, he told me some of the story of his life. It was then that I began to call him “Absalom.” The photo at the top of this post is Pornchai’s 2016 championship baseball team in which Pornchai, our old friend Chen (now in China), Absalom, and I are all pictured.

I do not think that I was even conscious at the time of the place in my psyche from which that name was dusted off. He did not object to being called “Absalom,” but it puzzled him.

It puzzled me, too. Absalom was the third son of King David in the Hebrew Scriptures, our Old Testament. In the Second Book of Samuel (15:1-12) Absalom rebelled against his father, staging a revolt that eventually led to his own demise. In the forest of Ephraim, Absalom was slain by Joab, David’s nephew and the commander of his armies. David bitterly mourned the loss of his son, Absalom (2 Samuel 19:1-4).

When I told this story to our new friend,he said, “that sounds like the right name for me.” I told him that in Hebrew, Absalom means “my father is peace.” But even as I said it, I remembered that Absalom is also the name of Pastor Stephen Kumalo’s missing son in Cry, the Beloved Country.

So I told my friend the story of how Absalom’s priest-father in South Africa had instilled in him a set of values and respect for his heritage, of how poverty and oppression caused him to leave home in search of another life only to be lured ever more deeply into the city streets of Johannesburg. I told of how his father sacrificed all to go in search of him.

I also told my friend that I read this book at age 15 in my own adolescent rebellion, and the story was so powerful that it has stayed with me for all these years and shaped some of the most important parts of my life. I told Absalom of the Zulu people and the struggles of Apartheid, a word he knew he once heard, but had no idea of what it meant. I told him that the Absalom of the story left behind his proud and spiritually rich African culture just to succumb to the lure of the street and of how he forgot all that came before him.

“That’s my story!” said Absalom when I told him all this. So the next day I went in search of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country. The prison library had a dusty old copy so I brought it back for Absalom to read, and he struggled with it. A part of the struggle is the Zulu names and terms that are vaguely familiar deep in our Absalom’s cultural memory. Another part of the struggle is the story itself, not just of Apartheid, but of the painful estrangement that grew between father and son, an estrangement that our Absalom could not articulate until now.

So then something that I always believed was going to happen, did happen. Absalom told me that he has contacted his mother to ask his father to visit him for the first time in the years that he has been in prison. He said they plan to visit on Father’s Day. They have a lot to talk about, and that is a drama for which I feel blessed to be in the supporting cast — all the rest of prison BS notwithstanding!

But there is something else. There is always something else. When I began writing this post, I asked Absalom to lend me his copy of Cry, the Beloved Country. When he brought it to me, he pointed out that he has only twenty pages left and wanted to finish it that night. “This is the first book I have ever read by choice,” he said, “and I don’t think I could ever forget it.” Neither could I.

As I thumbed through the book looking for a passage I remember reading 56 years ago (the one that begins this post), I came to a small bookmark near the end that Absalom used to mark his page. It was “A Prisoner’s Prayer to Saint Maximilian Kolbe.” I asked my friend where he got it, and he said, “It was in the book. I thought you put it there!” I did not. God only knows how many years that prayer sat inside that book waiting to be discovered, but here it is:

O Prisoner-Saint of Auschwitz, help me in my plight. Introduce me to Mary, the Immaculata, Mother of God. She prayed for Jesus in a Jerusalem jail. She prayed for you in a Nazi prison camp. Ask her to comfort me in my confinement. May she teach me always to be good.

If I am lonely, may she say, ‘Our Father is here.’

If I feel hate, may she say, ‘Our Father is love.’

If I sin, may she say, ‘Our Father is mercy.’

If I am in darkness, may she say, ‘Our Father is light.’

If I am unjustly accused, may she say, ‘Our Father is truth.’

If I lose hope, may she say, ‘Our Father is with you.’

If I am lost and afraid, may she say, ‘Our Father is peace.’

And that last line, you may recall, is the meaning of Absalom.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: South Africa is also home to Kruger National Park which forms its eastern border with Mozambique. Kruger National Park was also the setting for the most well read of our Fathers Day posts, the first those linked below:

In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men

Coming Home to the Catholic Faith I Left Behind

If Night Befalls Your Father, You Don’t Discard Him! You Just Don’t!

Saint Joseph: Guardian of the Redeemer and Fatherhood Redeemed

+ + +

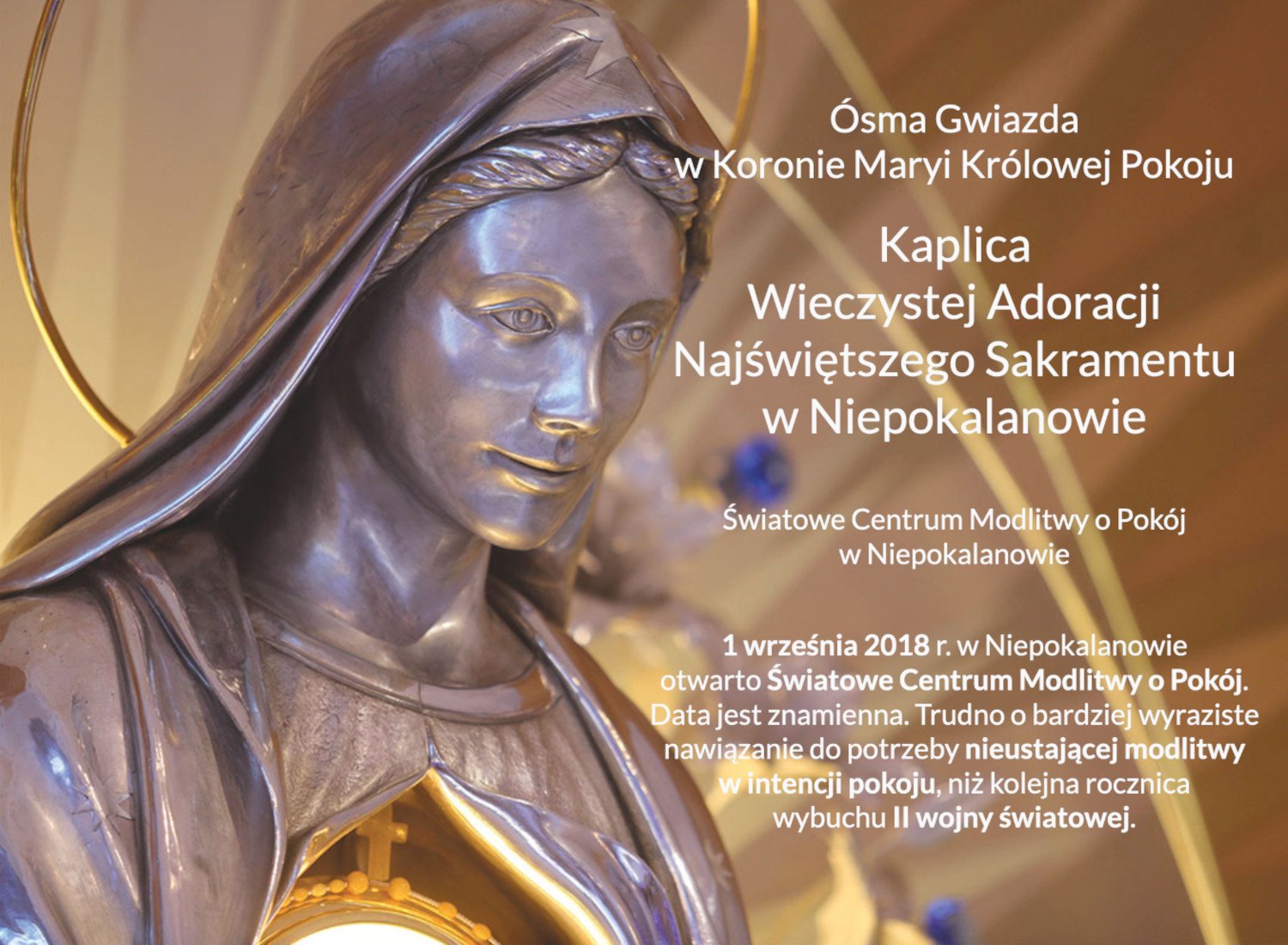

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men

Are committed fathers an endangered species in our culture? Fr. Gordon MacRae draws a troubling corollary between absent fathers and burgeoning prisons.

Are committed fathers an endangered species in our culture? Fr. Gordon MacRae draws a troubling corollary between absent fathers and burgeoning prisons.

Wade Horn, Ph.D., President of the National Fatherhood Initiative, had an intriguing article entitled “Of Elephants and Men” in a recent issue of Fatherhood Today magazine. I found Dr. Horn’s story about young elephants to be simply fascinating, and you will too. It was sent to me by a reader who wanted to know if there is any connection between the absence of fathers and the shocking growth of the American prison population.

Some years ago, officials at the Kruger National Park and game reserve in South Africa were faced with a growing elephant problem. The population of African elephants, once endangered, had grown larger than the park could sustain. So measures had to be taken to thin the ranks. A plan was devised to relocate some of the elephants to other African game reserves. Being enormous creatures, elephants are not easily transported. So a special harness was created to air-lift the elephants and fly them out of the park using helicopters.

The helicopters were up to the task, but, as it turned out, the harness wasn’t. It could handle the juvenile and adult female elephants, but not the huge African bull elephants. A quick solution had to be found, so a decision was made to leave the much larger bulls at Kruger and relocate only some of the female elephants and juvenile males.

The problem was solved. The herd was thinned out, and all was well at Kruger National Park. Sometime later, however, a strange problem surfaced at South Africa’s other game reserve, Pilanesburg National Park, the younger elephants’ new home.

Rangers at Pilanesburg began finding the dead bodies of endangered white rhinoceros. At first, poachers were suspected, but the huge rhinos had not died of gunshot wounds, and their precious horns were left intact. The rhinos appeared to be killed violently, with deep puncture wounds. Not much in the wild can kill a rhino, so rangers set up hidden cameras throughout the park.

The result was shocking. The culprits turned out to be marauding bands of aggressive juvenile male elephants, the very elephants relocated from Kruger National Park a few years earlier. The young males were caught on camera chasing down the rhinos, knocking them over, and stomping and goring them to death with their tusks. The juvenile elephants were terrorizing other animals in the park as well. Such behavior was very rare among elephants. Something had gone terribly wrong.

Some of the park rangers settled on a theory. What had been missing from the relocated herd was the presence of the large dominant bulls that remained at Kruger. In natural circumstances, the adult bulls provide modeling behaviors for younger elephants, keeping them in line.

Juvenile male elephants, Dr. Horn pointed out, experience “musth,” a state of frenzy triggered by mating season and increases in testosterone. Normally, dominant bulls manage and contain the testosterone-induced frenzy in the younger males. Left without elephant modeling, the rangers theorized, the younger elephants were missing the civilizing influence of their elders as nature and pachyderm protocol intended.

To test the theory, the rangers constructed a bigger and stronger harness, then flew in some of the older bulls left behind at Kruger. Within weeks, the bizarre and violent behavior of the juvenile elephants stopped completely. The older bulls let them know that their behaviors were not elephant-like at all. In a short time, the younger elephants were following the older and more dominant bulls around while learning how to be elephants.

Marauding in Central Park

In his terrific article, “Of Elephants and Men,” Dr. Wade Horn went on to write of a story very similar to that of the elephants, though it happened not in Africa, but in New York’s Central Park. The story involved young men, not young elephants, but the details were eerily close. Groups of young men were caught on camera sexually harassing and robbing women and victimizing others in the park. Their herd mentality created a sort of frenzy that was both brazen and contagious. In broad daylight, they seemed to compete with each other, even laughing and mugging for the cameras as they assaulted and robbed passersby. It was not, in any sense of the term, the behavior of civilized men.

Appalled by these assaults, citizens demanded a stronger and more aggressive police presence. Dr. Horn asked a more probing question. “Where have all the fathers gone?” Simply increasing the presence of police everywhere a crime is possible might assuage some political pressure, but it does little to identify and solve the real social problem behind the brazen Central Park assaults. It was the very same problem that victimized rhinos in that park in Africa. The majority of the young men hanging around committing those crimes in Central Park grew up in homes without fathers present.

That is not an excuse. It is a social problem that has a direct correlation with their criminal behavior. They were not acting like men because their only experience of modeling the behaviors of men had been taught by their peers and not by their fathers. Those who did have fathers had absent fathers, clearly preoccupied with something other than being role models for their sons. Wherever those fathers were, they were not in Central Park.

Dr. Horn pointed out that simply replacing fathers with more police isn’t a solution. No matter how many police are hired and trained, they will quickly be outnumbered if they assume the task of both investigating crime and preventing crime. They will quickly be outnumbered because presently in our culture, two out of every five young men are raised in fatherless homes, and that disparity is growing faster as traditional family systems break down throughout the Western world.

Real men protect the vulnerable. They do not assault them. Growing up having learned that most basic tenet of manhood is the job of fathers, not the police. Dr. Horn cited a quote from a young Daniel Patrick Moynihan written some forty years ago:

“From the wild Irish slums of the 19th Century Eastern Seaboard to the riot-torn suburbs of Los Angeles, there is one unmistakable lesson in American history: A community that allows a large number of young men to grow up in broken homes, dominated by women, never acquiring any stable relationship to male authority, never acquiring any rational expectations for the future — that community asks for and gets chaos.”

When Prisons Replace Parents

It’s easy in the politically correct standards of today to dismiss such a quote as chauvinistic. But while we’re arguing that point, our society’s young men are being tossed away by the thousands into prison systems that swallow them up. Once in prison, this system is very hard to leave behind. The New Hampshire prison system just released a dismal report two weeks ago. Of 1,095 prisoners released in 2007, over 500 were back in prison by 2010. Clearly, the loss of freedom does not compensate for the loss of fathers in managing the behavior of young men.

There is very little that happens in the punishment model of prison life that teaches a better way to a young man who has broken the law. The proof of that is all around us, but — especially in an election year — getting anyone to take a good hard look inside a prison seems impossible. We live in a disposable culture, and when our youth are a problem, we simply do what we do best. We dispose of them, sometimes forever. Anyone who believes that punishment, and nothing but punishment, is an effective deterrent of criminal behavior in the young is left to explain why our grotesquely expensive prisons have a 50 percent recidivism rate.

As I have written before, the United States has less than five percent of the world’s population, but twenty-five percent of the world’s prisoners. The U.S. has more young men in prison today than all of the leading 35 European countries combined. The ratio of prisoners to citizens in the U.S. is four times what it is in Israel, six times what it is in Canada and China, and thirteen times what it is in Japan. The only governments with higher per capita rates of prisoners are in Third World countries, and even they are only slightly higher.

For a nation struggling with its racial inequities, the prison system is a racial disaster. Currently, young men of African-American and Latino descent comprise 30 percent of our population, but 60 percent of our prison population. But prison isn’t itself an issue that falls conveniently along racial divides.

New Hampshire, where I have spent the last twenty-six years in prison, is one of the whitest states in the United States, and yet it is first in the nation not only in its Presidential Primary election, but in prison growth relative to population growth. Between 1980 and 2005, New Hampshire’s state population grew by 34 percent. In that same period, its prison population grew by a staggering 600 percent with no commensurate increase in crime rate.

In an election year, politicizing prisons is just counter-productive and nothing will ever really change. Albert R. Hunt of Bloomberg News had a recent op-ed piece in The New York Times (“A Country of Inmates,” November 20, 2011) in which he decried the election year politics of prisons.

“This issue [of prison growth] almost never comes up with Republican presidential candidates; one of the few exceptions was a debate in September when audiences cheered the notion of executions in Texas.”

This may be so, but it’s the very sort of political blaming that undermines real serious and objective study of our national prison problem. I am not a Republican or a Democrat, but in fairness I should point out that the recent Democratic governor of New Hampshire had but one plan for this State’s overcrowded and ever growing prison system: build a bigger prison somewhere. And as far as executions are concerned, the overwhelmingly Republican state Legislature in New Hampshire voted overwhelmingly to overturn the state’s death penalty ten years ago. Governor Jeanne Shaheen (now U.S. Senator Jeanne Shaheen), a Democrat, vetoed the repeal saying that this State “needs a death penalty.” (In 2020, the death penalty was finally rescinded in New Hampshire.)

More dismal still, New Hampshire is also first in the nation in deaths of young men between the ages of 16 and 34. This is largely attributed to opiates addiction and all the hopelessness it entails. Young men growing up in fatherless homes are exponentially more likely than any others to fall prey to addiction.

Eighty percent of the young men I have met in prison grew up in homes without fathers. The problem seems clear. When prisons and police replace fathers, chaos reigns, and promising young lives are sacrificed.

Before we close the door on Father’s Day this year, let’s revisit whether we’re prepared for the chaos of a fatherless America. “Fathers” and “Fatherhood” are concepts with 1,932 direct references in the Old and New Testaments. Without a doubt, fatherhood has long been on the mind of God.

+ + +

Don’t miss these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls: