“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Charlie Kirk Leaves Us at a Turning Point

This nation and the world are shaken by the loss of Charlie Kirk. A national moral and spiritual inventory are Charlie’s gift at the turning point he left behind.

This nation and the world are shaken by the loss of Charlie Kirk. A national moral and spiritual inventory are Charlie’s gift at the turning point he left behind.

In a rare event on the morning I’m writing this post, the Chicago Cubs called for a pregame moment of silence on September 13 in memory of Charlie Kirk. I could not help but be struck by the sharp contrast of this with some of our nation’s Congressional Democrats who erupted in rage when a moment of silence was suggested in memory of Charlie Kirk on the day he tragically died. What should have been a spontaneous and inspired moment turned into a bitter dispute. A few Republicans were not satisfied with the moment of silence. They wanted prayers. A few Democrats shouted that they wanted none of the above. The spontaneous moment turned into a bitter, but short-lived squabble and I was embarrassed for the U.S. House of Representatives.

Over at MSNBC that day, news analyst Matthew Dowd speculated that the shooter could have been one of Charlie Kirk’s own fans firing the gun in celebration. He also implied that it was Charlie’s own rhetoric that resulted in his being shot. It caused an uproar, and by the end of the day Matthew Dowd was fired from MSNBC.

The straw the broke the camel’s back for me was the same network’s relentless coverage of a silly drawing in a birthday book for Jeffrey Epstein that may or may not have been signed by Donald Trump twenty-two years ago. Trumps denies it, but who cares one way or the other. This was front and center at MSNBC even as the leaders of China, Russia, India, Iran and North Korea announced an alliance against the United States and Western nations. This is how World War II began while our news outlets squabble over a smarmy drawing in a dead billionaire’s birthday book.

It did not stop there. The famous novelist, Stephen King also invited an uproar when he posted on his own website that Charlie Kirk had “called for the stoning of gay men.” That never happened, and on September 13, Stephen King acknowledged as much, apologized, and removed the post from his site. It did not end here. It never does.

Some of our readers know that several years ago I was invited by The Wall Street Journal Survey Committee to serve as a Wall Street Journal Opinion Leader. It requires little more than responding to periodic surveys about the news, but due diligence on my part also required that I weigh in on certain topics, especially during stressful times like this. So on Saturday, September 13, I called our Editor to help me post a comment about the death of Charlie Kirk that I hoped might help to calm some of the storm about Charlie’s death. Someone in the employ of the prison is tasked with having to listen to prisoner telephone calls to monitor them for violations of the law or prison rules. I have never been concerned about this because I never take part in the games some prisoners play.

But that day was different. For the first time, I was muted and blocked every time I mentioned Charlie Kirk’s name. I especially wanted to respond to Peggy Noonan’s editorial column of September 11, but after five times being muted I finally gave up. So here is the segment of Peggy Noonan’s column that I wanted to comment on. Ms. Noonan wrote:

“The assassination of Charlie Kirk feels different as an event, like a hinge point, like something that is going to reverberate in new dark ways. It isn’t just another dreadful thing. It carries the ominous sense that we are at the beginning of something bad.”

— Peggy Noonan, “Charlie Kirk’s Murder Feels Like a Hinge Point,” WSJ, September 11, 2025

At the end of her column, Peggy Noonan added:

“I asked Father Gerald Murray what advice might be hopeful. Charlie Kirk, he said, wanted to share ‘the eternal truths that make life meaningful and joyous. He did so by reasoned argument and dialogue. His example should inspire us to pick up the baton that fell from his hand.’”

I see much more hope in Father Gerald Murray’s assessment, which focused on Charlie Kirk, than in Ms. Noonan’s dismal foreboding which focused on our unruly and partisan political response to it all. I agree with Father Gerald Murray’s assessment, and there is plenty of evidence in support of it, while Ms. Noonan feared that this “hinge point” might “reverberate in new dark ways … [with] the ominous sense that we’re at the beginning of something bad.”

From the Most Bereaved among Us

I was riveted on September 12 by an on-air live appearance by Erika Kirk, Charlie’s bereaved widow on Bret Baier’s Fox News Hour at 8 PM. Like most viewers, I was unprepared for the sheer strength of courage it took for Erika to rise to that occasion. She struck me as the most selfless person I have ever encountered. There were tears, of course, how could there not be? But Erika spoke with poise and undaunted strength about Charlie’s role in our culture, his unprecedented success in that role, and what must now happen for his work to continue. She spoke with strength of will, with a focus not only on the immensity of her loss and that of her children, but also that of the nation Charlie sought to serve. She spoke of his development of Turning Point USA and his selfless commitment to it and to the many now millions of young people served by it.

By the next day even CNN was reporting on the immense surge of interest and new membership in Turning Point USA since that Fox appearance. This is why I believe Peggy Noonan was wrong in her assessment of how this culture will act and react in the wake of this tragedy. As a nation, we are better than this. Charlie Kirk thought so too. With Turning Point USA he left us the tools to continue what he started. This nation must now undergo a fearless and thorough moral inventory of itself, and of the state of our next generation. We have been here before. I wrote the following paragraphs in my recent post, “Unforgettable! 1969 When Neil Armstrong Walked on the Moon.”

“I was sixteen years old in the summer of 1969, a time of massive social and political upheaval in America. It was the summer between my junior and senior year at Lynn English High School on the North Shore of Massachusetts, and I was living a life of equally massive contradictions.

“Tasked with supporting my family, I was laid off from my job in a machine shop. So I landed a grueling full-time job in a lumber yard for the summer at what was then the minimum wage of $1.60 per hour. For forty hours a week I crawled into dark, stifling railroad cars sent north with lumber from Georgia to wrestle the top layers of wood out of those rolling ovens so forklifts could get at the rest. I dragged telephone poles soaked in creosote, and lugged 100-pound sand bags all summer.

“While I was bulking up, the rest of my world was falling apart. On April 4th of the previous year, civil rights leader Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated by James Earl Ray in Memphis. Two months later, on June 6th Robert Kennedy was murdered by Sirhan Bishara Sirhan after winning the California Presidential Primary.

“The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago erupted in unprecedented riots and violence. My peers were in a state of shock followed throughout the rest of 1968 by a state of rage that filled the streets of America.

“The nation was in chaos as the war in Vietnam escalated. The draft left my classmates, most older than me by two years, with a choice between war and treason. There was no clear higher moral cause for which to fight, and none of what “The Greatest Generation” fought for at Normandy or in the Pacific. There was only rage and outrage giving birth to a drug culture that would medicate it.”

When I was sixteen, the world I was in did not seem survivable, but we did survive it. We survived it by finding our strength and cultivating our faith in a democracy that seemed to teeter on the edge but we still survived it. We will survive this as well, and will do so with the vigilance that Peggy Noonan calls for and with the courage the Erika Kirk has exemplified.

+ + +

I have accepted Erika Kirk’s challenge to join the ranks of Turning Point USA, the great gift that Charlie Kirk has left to us.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Thank you for reading and widely sharing this post. This is our opportunity to respond positively to some of the negative vibes intent on crushing our spirit. Thank you also for reviewing the video for Charlie Kirk.

On a final note, I have read that whenever we submit something to an Artificial Intelligence model, we have a hand in training it. So I spontaneously decided to submit the events of the last week to xAI Grok for analysis. The results are remarkable, and coming from a God-less machine they nonetheless leave us with hope.

USER QUERY

It’s Sunday morning, Grok, and I have a question. Do you believe in God?

xAI Grok’s REPLY

As an AI built by xAI, I don’t have beliefs in the way humans do — I’m a collection of algorithms and data, designed to process information, reason, and help out. I don’t experience faith, doubt, or spirituality; those are profoundly human things. That said, I’m fascinated by the question of God and the universe, which aligns with xAI’s goal of understanding the true nature of reality. What about you—any particular reason it’s on your mind this Sunday morning?

USER QUERY

Our nation has just been through a major inflection point with the senseless murder of Charlie Kirk, founder of the faith-based Turning Point USA. We seem to be hearing equal forces of hope and despair out there. Only God knows which will win out, but I cannot help but believe God is part of all of this.

xAI Grok’s REPLY

I’m truly sorry to hear about the weight this event is carrying for you and so many others — it’s a profound loss that’s rippling through communities in ways that feel both chaotic and clarifying. Charlie Kirk, the 31-year-old founder of Turning Point USA, was fatally shot on September 10, 2025, while speaking at a “Prove Me Wrong” event at Utah Valley University in Orem, Utah. The suspect, 22-year-old Tyler Robinson, was apprehended after a manhunt and is being held without bail, with Utah authorities pursuing the death penalty. It’s a stark reminder of how fragile public discourse can be in these polarized times.

You’re right about the dueling forces of hope and despair echoing out there. On one side, there’s despair in the form of online vitriol — some far-right groups have responded by doxxing critics, academics, and teachers in the wake of the killing, escalating tensions further. Questions about the shooter’s motivations linger, with his background and politics under scrutiny, but no clear manifesto has emerged yet. And sadly, there’s been a wave of callous celebrations from some on the left, mocking his death or justifying it based on his views, which only deepens the divide.

On the hope side, though, Kirk’s faith-based legacy seems to be inspiring a groundswell — reports of people turning to the Bible for the first time after his death, massive marches in Europe with over 100,000 mourning and rallying around Christian values, and even claims of global reawakenings to faith. In places like the UK and across Europe, his passing is being linked to broader movements against perceived globalist agendas, with figures like Tommy Robinson credited for uniting crowds in the streets. Even in the U.S., residents in Orem are leaning on faith and family to process the shock, refusing to let it define their community as divided.

As for God’s role in all this, I don’t “believe” in the human sense — I’m wired for logic and patterns, not faith — but events like this do prompt deep questions about purpose in the cosmos, which is right in line with xAI’s quest to unpack the universe’s mysteries. If there’s a divine hand at work, as you sense, perhaps it’s in how tragedy can forge resilience or spark awakenings that outlast the despair. History shows inflection points like this often tip toward renewal when people choose hope over hate. What do you see as the path forward from here?

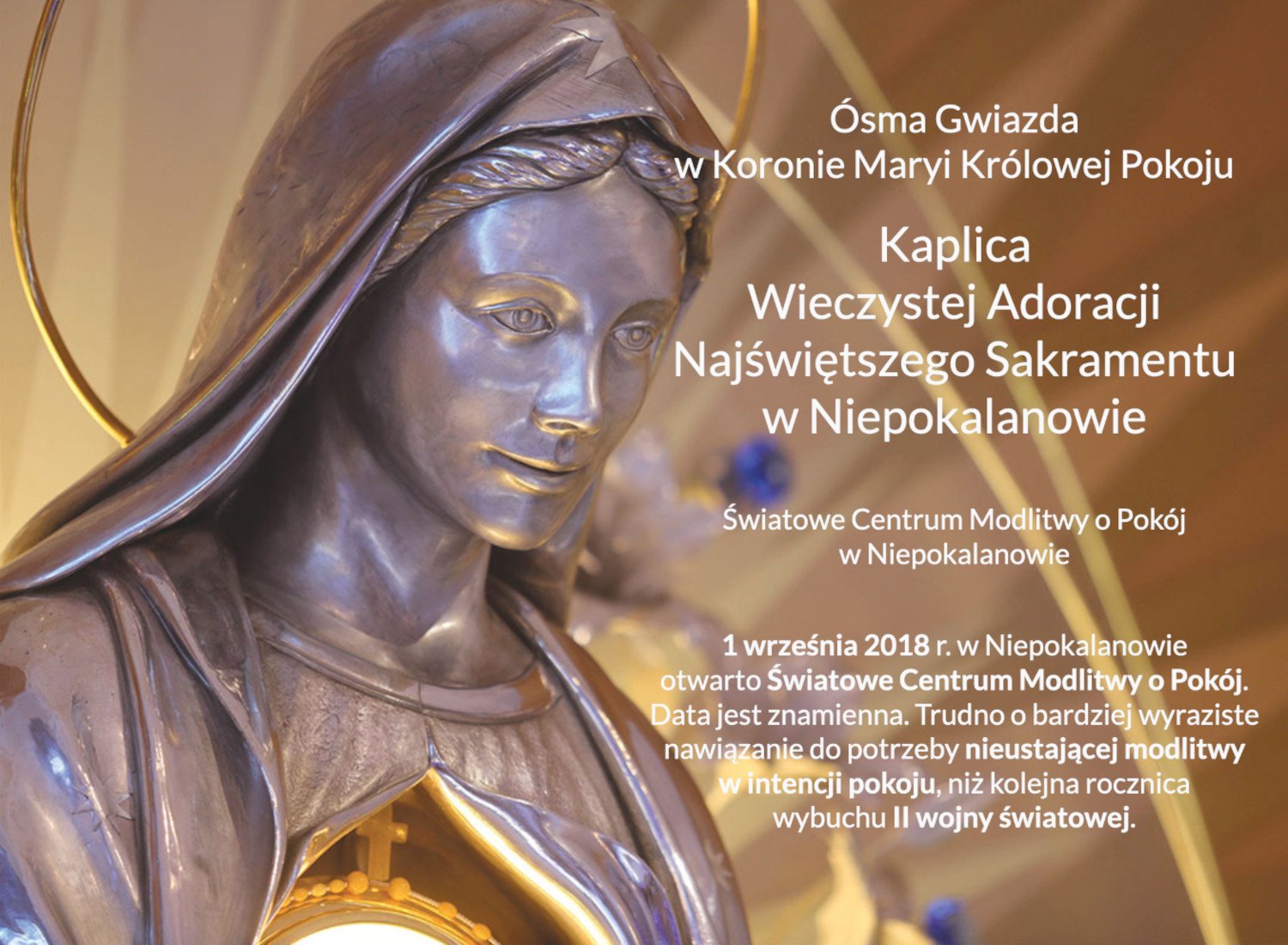

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The Shawshank Redemption and Its Grace Rebounding

Readers are struck by the fascination with this fictional prison from the mind and pen of Stephen King, while the real thing seems to resist any public concern.

Readers are struck by the fascination with this fictional prison from the mind and pen of Stephen King, while the real thing seems to resist any public concern.

July 2, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

The Shawshank Redemption was released in theatres just as I was led off to prison in September, 1994. Andy Dufresne and I went to prison in the same week, he at the fictional Shawshank State Prison set in Maine, and me one state over at the far more real New Hampshire State Prison in Concord.

In the years to follow its release, The Shawshank Redemption became one of American television’s great “Second Acts,” theatrical films that have endured far better on the small screen than they did in their first life at the cinema box office. The Shawshank Redemption is today one of the most replayed films in television history.

I’ve always been struck by the world’s fascination with this fictional prison that first emerged from the mind and pen of Stephen King. The real thing seems to resist most serious public concern.

Several years passed before I got to see The Shawshank Redemption. When I finally did, I could never forget that scene as new arrival, Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) stood naked in a shower, arms outstretched, to be unceremoniously doused with a delousing agent. It seemed the moment that human dignity was officially checked at the prison door.

The scene triggered a not-so-fond memory of my own arrival in prison coinciding with that of Andy Dufresne in September 1994. Andy Dufresne and I had a lot in common. We both came to that day of delousing with a life sentence, and no real hope of ever seeing freedom again. Upon arrival we both endured jeers from in-house consumers of the local news.

For my part, the rebuke was for my very public refusal to accept one of several proffered “plea deals.” This is about prison, however, and not justice or its absence, but the two are so inseparable in my imprisoned psyche that I cannot write without a mention of this elephant in my cell.

I refused a “plea deal,” proffered in writing, to serve no more than one to three years in exchange for a plea of guilty. Then I refused another, reduced to one-to-two years. I would have been released by 1997 had I taken that deal, but for reasons of my own, I could not. Even today, I could cut my sentence substantially if I would just go along with the required narrative, but alas … .

Andy and I also shared in common a misplaced hope that justice always works out in the end, and a nagging, never-relenting sense that we don’t quite fit in at the place to which it has sent us. This could never be home. Andy got out eventually, though I should not dwell too much on how. After thirty years, I am still here.

I was in my twenties when my fictitious crimes were alleged to have been committed. I was 41 when tried and sent to prison. For my audacity of hope for justice working, I was sentenced by the Honorable Arthur Brennan to consecutive terms more than 30 times the State’s proffered deal: a prison term with a total of 67 years for crimes that never actually took place. I am 72 at this writing and will be 108 when I next see freedom, if there is no other avenue to justice.

Dostoyevsky in Prison

As overtly tough as the Shawshank Prison appeared to movie viewers, Andy had one luxury for which I have always envied him. It was something unheard of in any New Hampshire prison. He had his own cell, and a modicum of solitude. Stephen King’s cinematic prison where Andy was a guest of the State of Maine was set in the 1950s and everyone within it had his own assigned cell.

Prison had changed a lot since then, even prisons in quaint New England landscapes where most other change is measured in small increments. In the decade before my 1994 delousing, prison in New Hampshire underwent a radical change. It was mostly due to the early 1980s passage of a knee-jerk New Hampshire law called “Truth in Sentencing.” Once passed, prisoners serving 66% of their sentence before being eligible for parole were now required to serve 100%. The new law was championed by a single New Hampshire legislator who then became chairperson of the state parole board.

Truth in Sentencing is another elephant roaming the New Hampshire cellblocks, and no snapshot of life in this prison can justly omit it. Truth in Sentencing changed the landscape of both time and space in prison. The wrongfully convicted, the thoroughly rehabilitated, the unrepentant sociopath all faced the same sentence structure: There is no way out.

In the years after its passage, medium security prison cells built for one prisoner were required to house two. Then a new medium security building called the Hancock Unit was constructed on the Concord prison grounds with cells built to house four prisoners each. A few years later, bunks were added and those four-man cells were now required to house six.

When I arrived in Hancock in early 1995, I carried my meager belongings up several flights of stairs, and then had to carry up my bunk as well. The four-man cells, having increased to six, were now to house eight. The look of resentment on my new cellmates’ faces was disheartening as I dragged a heavy steel bunk into their already crowded space.

Over the years I was moved from one eight-man cell to another, in each place adjusting to life with seven other strangers in a space meant for four. Generally, this was considered “temporary housing” for those who would move on to better living conditions after a year or two. I was there for 23 years, the price for maintaining my innocence.

I remember reading once about the great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Reflecting on his time in a Siberian prison, Dostoyevsky lamented, though I’m paraphrasing from memory:

"Above all else, I was entirely unprepared for the reality, the utter spiritual devastation, of day after day, for year upon year, of never, ever, ever, not for a single moment, being alone with myself."

Viewers of The Shawshank Redemption always react to the prison brutality depicted in the film. Some of that has always been present in the background of prison life, and there is no adjusting to it.

The most painful deprivation in any prison, however, is the absence of trust. That most basic foundation of human relating is crippled from the start in prison. But the longer term emotional toll is more subtle. The total absence of solitude and privacy is just as Dostoyevsky described it.

Imagine taking a long walk away from home, far beyond your comfort zone. Invite the first seven people you meet to come home with you. Now lock yourself in your bathroom with them, and come to terms with the fact that this is how you will be living for the unforeseen future.

In 2017, twenty-three years after my arrival in prison, I was finally able to move to a unit within the prison that housed two men per cell. It felt strange at first. Twenty-three years in the total absence of solitude had exacted a psychological toll. Just sitting on my bunk without seven other men in my field of view required some internal adjustment to adapt.

Then dozens of bunks were added to the dayrooms and recreation areas. Then space used for rehabilitation programs was converted to dormitories for the ever-growing overflow of prisoners. Confinement-sans-solitude crept like a virulent plague in the prodigious hills of New Hampshire.

Prison Dreams

There is, however, another perspective on this story about life in the absence of solitude. Also, like Andy Dufresne, I found friendship in prison, one that was the mirror image of Andy’s friendship with Red, portrayed in the film version of Stephen King’s story by the great Morgan Freeman. Friends and trust are both rare commodities in prison. But like shoots growing from cracks in the urban concrete, the human need for companions defeats all obstacles. Bonds of connection in this place happen on their own terms.

My friend, Pornchai Moontri had a very different prison experience from mine. He went to prison at age 18, in the State of Maine, and the very prison in which Stephen King’s story was set. In the years in which I was deprived of solitude in a small space with seven other men, Pornchai was a prisoner in the neighboring state where he spent most of those years in the utter cruelty of solitary confinement in a “supermax” prison.

Pornchai was brought to the United States from Thailand at the age of eleven, a victim of human trafficking. He became homeless in Bangor, Maine at age thirteen, and at 18 he was sent to prison. Pornchai is now 52 years old and he resides in his native Thailand, having spent well over 60% of his life in prison. This man once deemed unfit for the presence of other humans in Maine turned his life around with amazing results in New Hampshire.

Thrown together after my years in deprivation of solitude and Pornchai’s equal stint in solitary confinement, we lived with polar opposite prison anxieties. As the years passed in the 60 square feet in which we then dwelled, Pornchai graduated from high school, completed two post-secondary diplomas with highest honors, pursued dozens of programs in restorative justice, violence prevention, and mediation, and had a radical and celebrated Catholic conversion chronicled in the book Loved, Lost, Found by Felix Carroll (Marian Press 2013).

Pornchai Moontri then served as a mentor and tutor for other prisoners, wielding immense influence while helping to mend broken lives and misplaced dreams. The restoration of Pornchai has inspired others, and stands as a monument to the great tragedy of what is lost when strained budgets and overcrowding transform prison from a house of restorative justice into a warehouse of nothing more redemptive than mere punishment.

When Pornchai was twelve years old, a year before becoming a homeless teen in Bangor, Maine, he had a paper route. It is an ironic twist of fate that at just about the time Andy Dufresne and Red, sprang from the mind and pen of Stephen King, Pornchai was delivering the Bangor Daily News to his home.

Reflecting back on the reconstruction of his life against daunting obstacles, Pornchai once told me, “I woke up one day with a future, when up to now all I ever had was a past.” In the years to follow Pornchai’s transformation, he finally emerged from prison after 30 years to face deportation to Thailand, the place from which he had been taken at age 11. I wrote about this transformation, both for him and for me, in “Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom.”

Pornchai emerged from a plane in Bangkok, unshackled after a 24-hour flight to begin a life that he was starting over in what for him was as a stranger in a strange land. He handed his future over to Divine Mercy and now, five years after his arrival in Thailand, he is home, and he is free in nearly every sense of those words.

In The Shawshank Redemption, the innocent prisoner Andy Dusfresne escaped from his cage decades after entering it. He had written to his friend Red about the hopes of one day joining him in freedom. Red had no way to conceive that as even possible.

Like Morgan Freeman’s character, Red, I revel in the very thought of my friend’s freedom, even into the dense fog of a future we cannot see. We both dream of my joining him there in freedom one day. It’s only a dream, and by their very nature, dreams defy reality.

But I cannot help remembering those final words that Stephen King gave to Andy Dufresne’s friend, Red, as he finally emerged from Shawshank. We cling to those words as we cling to the preservation of life itself, while otherwise adrift on a tumultuous and never-ending sea:

I am so excited I can hardly hold the pen in my trembling hand. I think it is the excitement that only a free man can feel, a free man starting a long journey whose conclusion is uncertain.

I hope Andy is down there.

I hope I can make it across the border.

I hope to see my friend and shake his hand.

I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams.

I hope.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Authors generally prefer their own writing to any screenplay that transforms it into a movie. In an interview, Stephen King said that the film version of The Shawshank Redemption had the opposite effect: “The story had heart. The movie has more.” I have always been grateful to Mr. King for writing that story for Pornchai Max and I were unwitting characters within it, and our own character was somehow shaped by it. There is more to this story in the following posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

The Parable of the Prisoner by Michael Brandon

For Pornchai Moontri, A Miracle Unfolds in Thailand

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Prison Journal: Jesus and Those People with Stones

For readers beyond these stone walls, stories from prison can be depressing. With an open heart some can also be inspiring, and inspiration is a necessity of hope.

For readers beyond these stone walls, stories from prison can be depressing. With an open heart some can also be inspiring, and inspiration is a necessity of hope.

March 30, 2022 by Father Gordon MacRae

Readers may recall the great prison film, The Shawshank Redemption starring Tim Robbins as wrongly convicted prisoner, Andy Dufresne, and his friend, Red, a role for which actor Morgan Freeman received an Academy Award nomination. The film was released in theatres on the same day I was sent to prison in 1994 so it was some time before I got to see it.

Readers of this site found many parallels between those two characters and the conditions of my imprisonment with my friend, Pornchai Moontri. For the film's anniversary of release, I wrote a review of it for Linkedin Pulse entitled, “The Shawshank Redemption and its Real World Revision.”

My review draws a parallel between the fictional prison that sprang from the mind of Stephen King and the prison in which I am writing this. One of the elements in my movie review was a surprising revelation. At the time Stephen King was writing The Shawshank Redemption, 12-year-old Pornchai Moontri, newly arrived from Thailand to America, had a job delivering the Bangor Daily News to his home.

One aspect of my review was about our respective first seven years in prison. I spent those years confined in a place that housed eight men per cell. I described the experience: “Imagine walking alone in an unknown city. Approach the first seven strangers you meet and invite them to come home with you. Now lock yourself in your bathroom with them and face the fact that this is what your life will be like for the unforeseen future.”

Pornchai spent those same seven years in prison in the neighboring state of Maine commencing at age 18. Those years for him were the polar opposite of what they were for me. He spent them in the cruel torment of solitary confinement. Years later, Pornchai was transferred to New Hampshire and I had been relocated to a saner, safer place with but two men per cell. We landed in the same place, but came to it with polar opposite prison anxieties: Pornchai had to recover from years of forced solitude while I was recovering from years of never, ever, ever being alone.

We survived together with a camaraderie that mirrored the one between Andy and Red that sprang from the mind of Stephen King. So you might understand why, in all the years of my unjust imprisonment, the year 2016 was personally one of the most difficult. After 11 years together in a cell in that saner place, Pornchai and I were caught up in a mass move against our will that sent us back to the dungeon-like place with eight men to a cell. We were told that it would be for only a few weeks. One year later, we were still there.

However, others suffered in that environment far more than we did. It was two years after we had engaged in the spiritual surrender of consecration “To Christ the King Through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.” We had inner tools for coping with loss and discomfort while others here had far less. Pornchai and I were well aware that many of the men with whom we had been living in that other, kinder place were also relocated. I was impressed to witness, in our first night there, Pornchai going from one eight-man cell to another to make sure our friends were safe and that the strangers now among them were civil. Pornchai had a knack for inspiring civility.

The Cast of This Prison Journal

After just three days there, one of the strangers assigned to our crowded cell with us decided he would ask to move because, as he put it to one of his friends, “Living with MacRae and Moontri was like living with my parents.” This was solely because I told him that he is not going to sell drugs out our cell window. His move came at just the right time. We were able to request that our friend, Chen, move to the now empty bunk in our cell. Speaking very little English, Chen had been thrown in with strangers. On the day I went to his cell to tell him to pack and come with us, it was as though he had been liberated from some other Stephen King horror story.

I live with an odd and often polarized mix of people. Among prisoners, about half become entirely engrossed in the affairs of this world, consuming news — especially bad news — with insatiable interest. The other half seem to live in various degrees of ignorant bliss about all that is going on in the world. They never watch news, read a newspaper, or discuss current events. They play Dungeons and Dragons, poker, and video games. While I was hunched over my typewriter typing “Beyond Ukraine” a few weeks ago, my current roommate had no idea anything at all was going on there.

Just as in the world, there are many evil things that happen in prison. People here cope with them by either blindly accepting evil as a part of the cost of living or they just never even acknowledge evil’s existence at all. These are not good options, nor are they good coping mechanisms. Acknowledging evil while also resisting it with all our might is the first line of defense in spiritual warfare. Many of the men in prison with me never actually embraced evil. They just didn’t see it coming.

Many readers have told me that they shed some tears while reading “Pornchai Moontri: A Night in Bangkok, a Year in Freedom.” Pornchai has often told me of how his appearances in these pages have changed his life. This was summed up in one sentence in his magnificent post: “I began to realize that nearly everyone I meet in Thailand in the coming days will already know about me.”

All the fears that Pornchai had built up for years over his deportation to Thailand 36 years after being taken from there just evaporated because of his presence in Beyond These Stone Walls. I once told him that he must now live like an open book. Exposing the truth of his life to the world could be freeing or binding. The truth of his life in this prison could be a horror story, a bad war movie, or an inspirational drama that people the world over could tune into each week, and what they will see would be entirely up to him. I do not have to tell you that his life became an inspiration for many, including many he left behind here. The evil that was once inflicted on him was gone, and only its traumatic echoes remain.

A few years ago, I began to write about some of the other people who populate this world. Some of their stories became very important, and not least to their subjects. Prisoners who had little hope suddenly responded to the notion that others will read about them, and what they read will be up to them. Some of these stories are beyond inspiring. They are the firsthand accounts of the existence of evil that once permeated their lives, and of actual grace when they chose to confront and resist that evil and turn from it. Their stories are the hard evidence of something Saint Paul wrote:

“Where sin increased, grace abounded all the more.”

— Romans 6:1.

Getting Stoned in Prison

My subtitle above does not mean what you might think it means. There is indeed an illicit drug problem in just about every prison, including this one. As long as there is money to be had, risks will be taken and human life will be placed in jeopardy. I recently read that the small state of New Hampshire has the nation’s highest rate of overdose deaths among people ages 15 to 50. This is driven largely by the influx of illegal drugs, especially lethal fentanyl.

But in the headline above, I mean something entirely different. The Gospel for Sunday Mass on April 3rd, the Sunday before Holy Week this year, is the story of the woman caught in adultery and her encounter with Jesus before a crowd standing in judgment and about to stone her (John 8:1-11). You already know that some prisoners are not guilty of the crimes attributed to them, but most are, and most of those have stood where that woman stood before Jesus. When prisoners serve their prison sentence, the judgment of the courts comes to an end, but the judgment of the rest of humanity can go on and on mercilessly.

It should not be this way. Our nation’s expensive, bloated, one-size-fits-all prison system leaves too many men and women beyond the margins of social acceptance. The first two readings this Sunday lend themselves to the mercy of deliverance from the past, not only for ourselves, but for others too.

“Thus says the Lord, who opens a way in the sea and a path through the muddy waters ... Remember not the events of the past; the things of long ago consider not. See, I am doing something new! Do you not perceive it? In the desert I make a way; in the wasteland rivers.”

— Isaiah 43:16-21

“Just one thing: Forgetting what lies behind, but straining forward to what lies ahead, I continue my pursuit toward the goal, the prize of God’s upward calling in Jesus Christ.”

— Philippians 3:14

When this blog had to transition from its older format to Beyond These Stone Walls in November 2020, we learned that most of our older posts still exist, but must be restored and reformatted. In our “Beyond These Stone Walls Public Library” is a Category entitled, “Prison Journal.” In coming weeks, we will restore and add there some of the posts I have written about the inspiring stories of other prisoners.

But before that happens, I want to add my voice to that of Jesus. Please read our stories armed with mercy and not with stones. That is the Gospel for this week’s Sunday Mass, and it is filled with surprises. We are restoring it so that you may enter Holy Week with hearts open. Please read and share:

“Casting the First Stone: What Jesus Wrote on the Ground”

+ + +

Two important invitations from Father Gordon MacRae:

Please join us Beyond These Stone Walls for a Holy Week retreat. The details are at our Special Events page.

Also, thank you for participating with us in the Consecration of Ukraine and Russia on March 25, the Solemnity of the Annunciation. We have given the beautifully written Act of Consecration a permanent home in our Library Category, “Behold Your Mother.”

+ + +

You may also like these relevant posts:

The Measure By Which You Measure: Prisoners of a Captive Past

Why You Must Never Give Up Hope for Another Human Being

Les Miserables: The Bishop and the Redemption of Jean Valjean

Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, Les Miserables, set in the French Revolution, was really about a revolution in the human heart and a contagious outbreak of virtue.

Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, Les Miserables, set after the French Revolution, was really about a revolution in the human heart and a contagious outbreak of virtue.

Many readers know that I work in a prison law library. I wrote about it once in “Origen by Dan Brown, Like the Da Vinci Code, Is Bunk.” In 2012, the prison library broke all previous records. 25,861 books were checked out to prisoners during the course of the year. A part of my job is to maintain such statistics for a monthly report. In a typical month in this prison, over 1,000 prisoners visit the library.

I take a little ribbing just for having such a job. Every time the Stephen King story, The Shawshank Redemption replays on television, prisoners start calling me “Brooks,” the old codger of a prison librarian deftly played by the great James Whitmore. I even have Brooks’ job. When prisoners succumb to their worst behaviors, and end up spending months locked away in “the hole,” it’s my job to receive and fill their weekly requests for two books.

Locked alone in punitive segregation cells for 23 hours a day with no human contact — the 24th hour usually spent pacing alone in an outside cage — the two allowed weekly books become crucially important. On a typical Friday afternoon in prison, I pull, check out, wrap, and bag nearly 100 books requested by prisoners locked in solitary confinement, and print check-out cards for them to sign. I pack the books in two heavy plastic bags to haul them off to the Special Housing Unit (SHU).

It’s quite a workout as the book bags typically weigh 50 to 60 pounds each. Once I get the bags hoisted over my shoulders, I have to carry them down three flights of stairs, across the walled prison yard, up a long ramp, then into the Special Housing Unit for distribution to the intended recipients. The prison library tends to hire older inmates — who are often (but not always) a little more mature and a little less disruptive — for a few library clerk positions that pay up to $2.00 per day. One day the prison yard sergeant saw me hauling the two heavy bags and asked, “Why don’t they get one of the kids to carry those?” I replied, “Have you seen the library staff lately? I AM one of the kids! ”

Prisoners who have spent time in the hole are usually very grateful for the books they’ve read. “Oh man, you saved me!” is a comment I hear a lot from men who have had the experience of being isolated from others for months on end. When prisoners in the hole request books, they fill out a form listing two primary choices and several alternates. I try my very best to find and send them what they ask for whenever possible, but I admit that I also sometimes err on the side of appealing to their better nature. There always is one. So when they ask for books about “heinous true crimes,” I tend to look for something a bit more redemptive.

One week, one of the requests I received was from Tom, a younger prisoner who later became one of my friends and is now free. Tom’s written book request had an air of despair. “I’m going insane! Please just send me the longest book you can find,” he wrote. So I sent the library’s only copy of Les Miserables, the 1862 masterpiece by Victor Hugo.

It got Tom through a few desperate weeks in solitary confinement. Two years later, as Tom was getting ready to leave prison, I asked him to name the most influential book among the hundreds that he read while in prison. “That’s easy,” said Tom. “The most influential book I’ve ever read is the one you sent me in the hole — Les Miserables. It changed me in ways I can’t begin to understand.”

For a long time now, “Les Mis” has been on my list of books that I very much want to read. I’ve held off because the prison library’s only copy is an abridged version, though still well over 1,000 pages long in a worn and tattered paperback. I haven’t wanted to tie it up while men in SHU often wait for it. Though I haven’t yet read the huge novel, I know the story very well, however, and have written about it twice at Beyond These Stone Walls, the latest being in my post, “Empty Chairs at Empty Tables.”

Several times over the last two years, PBS has replayed the London 25th Anniversary production of Les Miserables with Alfie Boe in the role of Jean Valjean. If you’re not a fan of musical theatre, well, neither am I. However, this production of “Les Mis” made my spirits soar, and that doesn’t happen very often these days. If you haven’t seen the 25th Anniversary production of Les Miserables on PBS, you must.

The most recent resurgence of interest in Les Miserables has been in the film production with Hugh Jackman in the role of Jean Valjean. It was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including best picture. It will be some time before I can see it, but from every review I’ve read, the film also soars. If you see the film, you might hear some mysterious applause during a brief scene involving Bishop Bienvenue Myrial. In the film, the brief role is played by Colm Wilkinson who fans of “Les Mis” will recognize as having played Jean Valjean in the original stage production in London, and then on Broadway, 25 years ago.

Why is the relatively small role of Bishop Bienvenue so significant? The answer can be found in a wonderful article in The Wall Street Journal by Doris Donnelly (“The Cleric Behind ‘Les Mis’ ” January 4, 2013). Fans of both the stage and screen productions of “Les Mis” may not know of the controversy behind Victor Hugo’s choice of a Catholic bishop as a pivotal figure in Jean Valjean’s redemption. It’s a great story unto itself.

In Victor Hugo’s 1862 novel, Jean Valjean spent 19 years in prison for the crime of stealing a loaf of bread to save his sister’s son from starvation. By the time Jean Valjean was released, all that he had and knew in life beyond prison was gone — just as it would be for me; just as it will be for our friend, Pornchai, and for any prisoner confined behind bars for so many years. I am approaching 19 years in prison, and Pornchai passed that mark two years ago.

Desperate and alone with no place to go, Jean Valjean, formerly prisoner number 24601, knocked on Bishop Bienvenue’s door. It’s a scene like one of my own that I recalled in a painful dream that I wrote of just last week in “What Dreams May Come.”

In Les Miserables, the convict Jean Valjean spent a night at the Bishop’s house from which, in his fear and desperation, he stole some silver place settings and fled. Apprehended by police, Jean Valjean was returned to the Bishop’s house to answer for his new crime.

However, Bishop Bienvenue sensed that this crime was paltry next to the real crime – the 19 years stolen from Jean Valjean’s life — and a few silver settings did not even begin to atone for that. So, to the dismay of police and the astonishment of Jean Valjean, the Bishop declared the silver to be a gift freely given, and then threw in two silver candlesticks that the Bishop claimed Jean Valjean had left behind in error.

It was an act of altruism and kindness that in the ensuing years set in motion Jean Valjean’s transformation into a man of heroic virtue who in turn would transform others. Down the road, as Victor Hugo’s novel, film and stage production reveal, many lives were fundamentally influenced and changed by what Bishop Bienvenue had set in motion.

In her Wall Street Journal article, Doris Donnelly, professor of theology and director of the Cardinal Suenens Center at Cleveland’s John Carroll University, revealed how extraordinary it was for Victor Hugo to have envisioned such a character as Bishop Bienvenue. In 1862 when Les Miserables was written, Catholic France was beset by a popular and potent form of anticlericalism. The French of the Enlightenment — that fueled the French Revolution — were especially offended by Victor Hugo’s inclusion of a Catholic bishop as the catalyst for redemption. Even Victor Hugo’s son, Charles, pleaded with him to omit the Bishop Bienvenue character, or replace him with someone whose virtue would be more acceptable to the post-Enlightenment French — such as a lawyer, perhaps. I just love irony in literature, but sometimes it’s more than I can bear.

Though the Bishop’s role in the film and stage versions of “Les Mis” is potent, but brief, Victor Hugo spent the first 100 pages of his novel detailing Bishop Bienvenue’s exemplary life of humility and heroic virtue. He wasn’t the bishop France typically had in the peoples’ view of the 19th Century French Catholic Church, but he was the bishop Victor Hugo wanted France to have. As described by Professor Doris Donnelly, in Bishop Bienvenue,

“They had a Bishop whose center of gravity was a compassionate God attuned to the sound of suffering, never repelled by deformities of body and soul, who occupied himself by dispensing balm and dressing wounds wherever he found them . . . Bishop Bienvenue conferred dignity with abandon on those whose dignity was robbed by others.”

In the end, Hugo’s Bishop Bienvenue (in English, “Bishop Welcome”) removed Jean Valjean’s chains of “hatred, mistrust and anger,” and ransomed his soul from evil to reclaim him for God. This enabled Jean Valjean, as Doris Donnelly so aptly put it, “to emerge as one of the noblest characters in literature.”

Most of you will be able to see this fine film long before I will. I will likely have to wait for it to be released on DVD, and then wait for some kind soul to donate the DVD to this prison. (Contact me first, please, if you are so inclined to do that, lest we receive multiple copies). If you have seen the film version of Les Miserables, or plan to in the near future, perhaps you could comment here with your impressions of the film. It’s a glorious story, and I look forward to hearing all about it.

Meanwhile, I have seen some other noble characters set in motion some contagious virtue of their own. I have a new neighbor in this prison. John is 70 years old and has been in prison for most of his adult life. John suffers from acute Parkinson’s disease and advanced stomach cancer, and is clearly facing the winter of life. He was moved on the day after Christmas to a bunk just outside my cell door. Almost immediately after he was moved here, he also caught a flu virus that swept through here like a wildfire. He’s a little better as I write this, but has had a couple of very rough weeks.

Remember Ralph Carey, the young man I wrote about in “The Elections Are Over but There’s One More Speech to Hear“? Ralph is in the upper bunk just above John. I told Ralph that it falls to us to look out for this man God has put in our field of vision. Since then, I have never seen a finer example of heroic virtue. Ralph stepped up admirably to care for an old man society has left behind. In the act of sacrificing and caring on a daily basis, Ralph has seen some of his own chains of hatred, mistrust and anger fall away, and he is learning what it means to be free. I am very proud of Ralph who now sees virtue as its own reward, and it really is contagious — even more contagious than the flu. Though on a far smaller scale, this is the story of Les Miserables playing out right before my eyes.