The Shawshank Redemption and Its Grace Rebounding

Readers are struck by the fascination with this fictional prison from the mind and pen of Stephen King, while the real thing seems to resist any public concern.

July 2, 2025 by Father Gordon MacRae

The Shawshank Redemption was released in theatres just as I was led off to prison in September, 1994. Andy Dufresne and I went to prison in the same week, he at the fictional Shawshank State Prison set in Maine, and me one state over at the far more real New Hampshire State Prison in Concord.

In the years to follow its release, The Shawshank Redemption became one of American television’s great “Second Acts,” theatrical films that have endured far better on the small screen than they did in their first life at the cinema box office. The Shawshank Redemption is today one of the most replayed films in television history.

I’ve always been struck by the world’s fascination with this fictional prison that first emerged from the mind and pen of Stephen King. The real thing seems to resist most serious public concern.

Several years passed before I got to see The Shawshank Redemption. When I finally did, I could never forget that scene as new arrival, Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) stood naked in a shower, arms outstretched, to be unceremoniously doused with a delousing agent. It seemed the moment that human dignity was officially checked at the prison door.

The scene triggered a not-so-fond memory of my own arrival in prison coinciding with that of Andy Dufresne in September 1994. Andy Dufresne and I had a lot in common. We both came to that day of delousing with a life sentence, and no real hope of ever seeing freedom again. Upon arrival we both endured jeers from in-house consumers of the local news.

For my part, the rebuke was for my very public refusal to accept one of several proffered “plea deals.” This is about prison, however, and not justice or its absence, but the two are so inseparable in my imprisoned psyche that I cannot write without a mention of this elephant in my cell.

I refused a “plea deal,” proffered in writing, to serve no more than one to three years in exchange for a plea of guilty. Then I refused another, reduced to one-to-two years. I would have been released by 1997 had I taken that deal, but for reasons of my own, I could not. Even today, I could cut my sentence substantially if I would just go along with the required narrative, but alas … .

Andy and I also shared in common a misplaced hope that justice always works out in the end, and a nagging, never-relenting sense that we don’t quite fit in at the place to which it has sent us. This could never be home. Andy got out eventually, though I should not dwell too much on how. After thirty years, I am still here.

I was in my twenties when my fictitious crimes were alleged to have been committed. I was 41 when tried and sent to prison. For my audacity of hope for justice working, I was sentenced by the Honorable Arthur Brennan to consecutive terms more than 30 times the State’s proffered deal: a prison term with a total of 67 years for crimes that never actually took place. I am 72 at this writing and will be 108 when I next see freedom, if there is no other avenue to justice.

Dostoyevsky in Prison

As overtly tough as the Shawshank Prison appeared to movie viewers, Andy had one luxury for which I have always envied him. It was something unheard of in any New Hampshire prison. He had his own cell, and a modicum of solitude. Stephen King’s cinematic prison where Andy was a guest of the State of Maine was set in the 1950s and everyone within it had his own assigned cell.

Prison had changed a lot since then, even prisons in quaint New England landscapes where most other change is measured in small increments. In the decade before my 1994 delousing, prison in New Hampshire underwent a radical change. It was mostly due to the early 1980s passage of a knee-jerk New Hampshire law called “Truth in Sentencing.” Once passed, prisoners serving 66% of their sentence before being eligible for parole were now required to serve 100%. The new law was championed by a single New Hampshire legislator who then became chairperson of the state parole board.

Truth in Sentencing is another elephant roaming the New Hampshire cellblocks, and no snapshot of life in this prison can justly omit it. Truth in Sentencing changed the landscape of both time and space in prison. The wrongfully convicted, the thoroughly rehabilitated, the unrepentant sociopath all faced the same sentence structure: There is no way out.

In the years after its passage, medium security prison cells built for one prisoner were required to house two. Then a new medium security building called the Hancock Unit was constructed on the Concord prison grounds with cells built to house four prisoners each. A few years later, bunks were added and those four-man cells were now required to house six.

When I arrived in Hancock in early 1995, I carried my meager belongings up several flights of stairs, and then had to carry up my bunk as well. The four-man cells, having increased to six, were now to house eight. The look of resentment on my new cellmates’ faces was disheartening as I dragged a heavy steel bunk into their already crowded space.

Over the years I was moved from one eight-man cell to another, in each place adjusting to life with seven other strangers in a space meant for four. Generally, this was considered “temporary housing” for those who would move on to better living conditions after a year or two. I was there for 23 years, the price for maintaining my innocence.

I remember reading once about the great Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Reflecting on his time in a Siberian prison, Dostoyevsky lamented, though I’m paraphrasing from memory:

"Above all else, I was entirely unprepared for the reality, the utter spiritual devastation, of day after day, for year upon year, of never, ever, ever, not for a single moment, being alone with myself."

Viewers of The Shawshank Redemption always react to the prison brutality depicted in the film. Some of that has always been present in the background of prison life, and there is no adjusting to it.

The most painful deprivation in any prison, however, is the absence of trust. That most basic foundation of human relating is crippled from the start in prison. But the longer term emotional toll is more subtle. The total absence of solitude and privacy is just as Dostoyevsky described it.

Imagine taking a long walk away from home, far beyond your comfort zone. Invite the first seven people you meet to come home with you. Now lock yourself in your bathroom with them, and come to terms with the fact that this is how you will be living for the unforeseen future.

In 2017, twenty-three years after my arrival in prison, I was finally able to move to a unit within the prison that housed two men per cell. It felt strange at first. Twenty-three years in the total absence of solitude had exacted a psychological toll. Just sitting on my bunk without seven other men in my field of view required some internal adjustment to adapt.

Then dozens of bunks were added to the dayrooms and recreation areas. Then space used for rehabilitation programs was converted to dormitories for the ever-growing overflow of prisoners. Confinement-sans-solitude crept like a virulent plague in the prodigious hills of New Hampshire.

Prison Dreams

There is, however, another perspective on this story about life in the absence of solitude. Also, like Andy Dufresne, I found friendship in prison, one that was the mirror image of Andy’s friendship with Red, portrayed in the film version of Stephen King’s story by the great Morgan Freeman. Friends and trust are both rare commodities in prison. But like shoots growing from cracks in the urban concrete, the human need for companions defeats all obstacles. Bonds of connection in this place happen on their own terms.

My friend, Pornchai Moontri had a very different prison experience from mine. He went to prison at age 18, in the State of Maine, and the very prison in which Stephen King’s story was set. In the years in which I was deprived of solitude in a small space with seven other men, Pornchai was a prisoner in the neighboring state where he spent most of those years in the utter cruelty of solitary confinement in a “supermax” prison.

Pornchai was brought to the United States from Thailand at the age of eleven, a victim of human trafficking. He became homeless in Bangor, Maine at age thirteen, and at 18 he was sent to prison. Pornchai is now 52 years old and he resides in his native Thailand, having spent well over 60% of his life in prison. This man once deemed unfit for the presence of other humans in Maine turned his life around with amazing results in New Hampshire.

Thrown together after my years in deprivation of solitude and Pornchai’s equal stint in solitary confinement, we lived with polar opposite prison anxieties. As the years passed in the 60 square feet in which we then dwelled, Pornchai graduated from high school, completed two post-secondary diplomas with highest honors, pursued dozens of programs in restorative justice, violence prevention, and mediation, and had a radical and celebrated Catholic conversion chronicled in the book Loved, Lost, Found by Felix Carroll (Marian Press 2013).

Pornchai Moontri then served as a mentor and tutor for other prisoners, wielding immense influence while helping to mend broken lives and misplaced dreams. The restoration of Pornchai has inspired others, and stands as a monument to the great tragedy of what is lost when strained budgets and overcrowding transform prison from a house of restorative justice into a warehouse of nothing more redemptive than mere punishment.

When Pornchai was twelve years old, a year before becoming a homeless teen in Bangor, Maine, he had a paper route. It is an ironic twist of fate that at just about the time Andy Dufresne and Red, sprang from the mind and pen of Stephen King, Pornchai was delivering the Bangor Daily News to his home.

Reflecting back on the reconstruction of his life against daunting obstacles, Pornchai once told me, “I woke up one day with a future, when up to now all I ever had was a past.” In the years to follow Pornchai’s transformation, he finally emerged from prison after 30 years to face deportation to Thailand, the place from which he had been taken at age 11. I wrote about this transformation, both for him and for me, in “Pornchai Moontri and the Long Road to Freedom.”

Pornchai emerged from a plane in Bangkok, unshackled after a 24-hour flight to begin a life that he was starting over in what for him was as a stranger in a strange land. He handed his future over to Divine Mercy and now, five years after his arrival in Thailand, he is home, and he is free in nearly every sense of those words.

In The Shawshank Redemption, the innocent prisoner Andy Dusfresne escaped from his cage decades after entering it. He had written to his friend Red about the hopes of one day joining him in freedom. Red had no way to conceive that as even possible.

Like Morgan Freeman’s character, Red, I revel in the very thought of my friend’s freedom, even into the dense fog of a future we cannot see. We both dream of my joining him there in freedom one day. It’s only a dream, and by their very nature, dreams defy reality.

But I cannot help remembering those final words that Stephen King gave to Andy Dufresne’s friend, Red, as he finally emerged from Shawshank. We cling to those words as we cling to the preservation of life itself, while otherwise adrift on a tumultuous and never-ending sea:

I am so excited I can hardly hold the pen in my trembling hand. I think it is the excitement that only a free man can feel, a free man starting a long journey whose conclusion is uncertain.

I hope Andy is down there.

I hope I can make it across the border.

I hope to see my friend and shake his hand.

I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams.

I hope.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Authors generally prefer their own writing to any screenplay that transforms it into a movie. In an interview, Stephen King said that the film version of The Shawshank Redemption had the opposite effect: “The story had heart. The movie has more.” I have always been grateful to Mr. King for writing that story for Pornchai Max and I were unwitting characters within it, and our own character was somehow shaped by it. There is more to this story in the following posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

The Parable of the Prisoner by Michael Brandon

For Pornchai Moontri, A Miracle Unfolds in Thailand

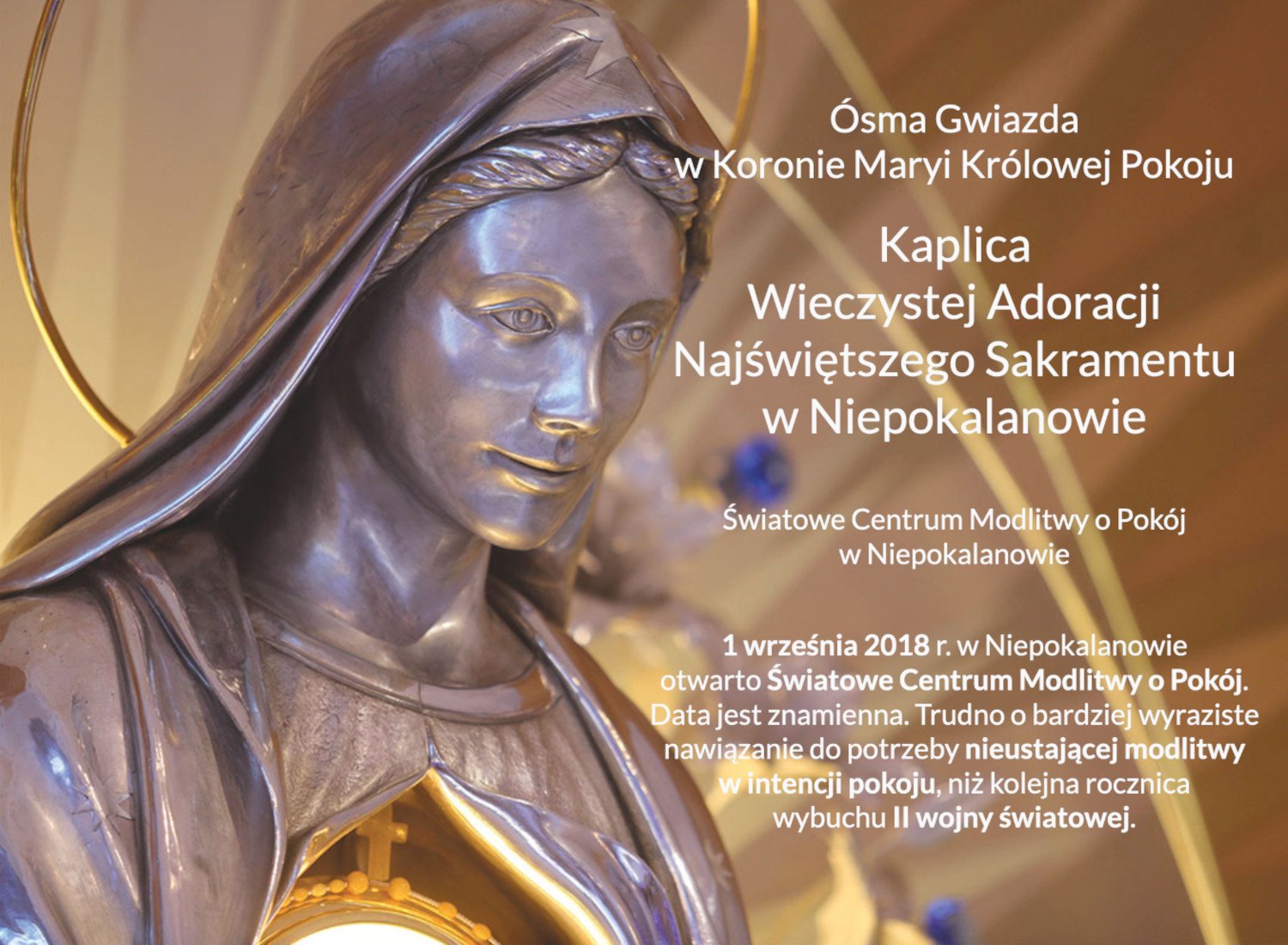

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”