“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Fr Seraphim Michalenko on a Mission of Divine Mercy

Midway in our Consoling the Heart of Jesus retreat in prison, Fr Seraphim Michalenko, Director of the National Shrine of The Divine Mercy, fulfilled Hebrews 13:3.

Midway in our Consoling the Heart of Jesus retreat in prison, Fr Seraphim Michalenko, Director of the National Shrine of The Divine Mercy, fulfilled Hebrews 13:3.

Some strange and interesting things are happening behind These Stone Walls this summer, and it’s a task and a half to stay ahead of them and reflect a little so I can write of them. In too many ways to describe, we sometimes feel swept off our feet by the intricate threads of connection that are being woven, and sometimes revealed.

I wasn’t even going to have a post for this week. I spent the last ten days immersed in a major writing project that I just finished. I knew it would be a struggle to type a post on top of that. I also had no topic. Absolutely nothing whatsoever came to mind. So I decided to just let readers know that I need to skip a week on TSW. Yet here I am, and it’s being written on the fly as I struggle to type it and get it in the mail in time.

What brought on this frenzy to get something posted on this mid-summer day? Well, first of all I awoke this morning and looked at the calendar, and realized that the post date I decided to skip is also the Memorial of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. It commemorates the apparition of our Blessed Mother to Saint Simon Stock, founder of the Carmelite Order, in the year 1215. She promised a special blessing to those who would wear her scapular. According to the explanation of this Memorial in the Daily Roman Missal, “Countless Christians have taken advantage of Our Lady’s protection.”

“Protection.” It seems a strange word to describe what we might expect from devotion to Mary. Most TSW readers remember my post, “Behold Your Mother! 33 Days to Morning Glory” about the Marian Consecration which Pornchai Maximilian and I entered into on the Solemnity of Christ the King in 2013. Felix Carroll also wrote of it — with a nice photo of us — in “Mary is at Work Here” in Marian Helper magazine. [Flash Version and PDF Version]

Throughout that 33 Days retreat leading up to our Consecration, I was plagued with the creepy feeling that this was all going to cost us something, that maybe Pornchai and I were opening ourselves to further suffering and trials by Consecrating to Mary the ordeals we are now living. What we have both found since our Marian Consecration, however, has been a sort of protection, a subtle grace that seems to be weaving itself in and around us, permeating our lives. Exactly what has been its cost? It has cost us something neither of us ever imagined we could ever afford to pay. The price tag for such grace is trust, and where we live, that is a precious commodity not so easily invested, but very easily taken from us.

I am amazed at the number of TSW readers who have written to me about their decisions to commence the 33 Days retreat, and commit themselves to Marian Consecration. I received a letter this week from Mary Fran, a reader and frequent correspondent who is completing her 33 Days retreat with her Marian Consecration on the day this is posted, the Memorial of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. She is going into this with just the right frame of mind and spirit. I hope she doesn’t mind, but here’s an excerpt of her letter:

“This is a very good retreat. I will be sorry to see it over. I have the Consecration Prayer typed out on pretty paper in preparation for the big day. A new beginning. A new way of life. Under new management.”

The truth is, Mary Fran, that it will never be over. But I like your idea of a life “under new management.” The concept seems to have a lot less to do with what Marian Consecration might cost in terms of trials to be offered, and more to do with what graces might be gained to endure them when they come. I’m not sure of why or exactly when it started, but after receiving the Eucharist since my own Consecration I have begun to pray the Memorare, a prayer attributed to Saint Bernard of Clairvaux that best expresses our confidence in Mary as repository of grace and, therefore, protection:

“Remember, O most gracious Virgin Mary, that never was it known that anyone who fled to your protection, implored your help, or sought your intercession was left unaided. Inspired with this confidence, I fly unto you, O Virgin of virgins, my Mother. To you I come, sinful and sorrowful. O Mother of the Word incarnate, despise not my petitions, but in your mercy hear and answer me. Amen.”

Trust Is the Currency of Grace

In a post last month, “Father’s Day in Prison Consoling the Heart of Jesus,” I wrote a little about how much of a daily ordeal our prisons can sometimes be. Near the end of that post, I quoted a brief dialogue between Father Michael Gaitley, author of Consoling the Heart of Jesus, and Father Seraphim Michalenko, Director of The National Shrine of The Divine Mercy. Their discussion is worth expanding a bit for this post. In fact, it was part of this week’s assigned reading in our Consoling the Heart of Jesus retreat in which we are at the midway point behind these prison walls. So here is a little more of that conversation:

“Father Gaitley: ‘And we want to console Jesus in the best possible way … and the best way to console Him is to remove the thorn that hurts His heart the most, the thorn that is lack of trust in His merciful love … and the best way to remove that thorn and console Him is to trust Him.’

”Father Seraphim: ‘And how do you LIVE trust? What is its concrete expression in your daily 1iving? … The way you live that trust is by praise and thanksgiving, to praise and thank God in all things. That’s what the Lord said to St. Faustina.’”

It struck me just today that the new trial asked of me in Marian Consecration is to imitate her trust, her famous fiat to the seemingly impossible: “Be it done to me according to Thy word.” Such trust is not an easy thing to embrace when the world turns dark, when freedom is taken by forces beyond our control, when fortune fades, when health fails, when loved ones are lost, when love itself is lost, when evil seems to win all around us, when depression, the noon-day devil, wants to rule both day and night.

That almost seems to sum up prison, and as such we are all destined for the trials of life in some form or another. We are all destined for some form of prison. So many readers have asked me for an update on our friend, Anthony, of whom I wrote recently in “Pentecost, Priesthood, and Death in the Afternoon.” Anthony is in prison dying of cancer. Several weeks ago, he could no longer bear the pain he was in so he was moved to the prison medical unit for palliative care. He came to the prison chapel for Mass the following Sunday, and the one after that. He was not there at Mass last week, and it is very possible we will not see Anthony again in this life.

Though he is but 200 yards away locked in another building, prisons pay no heed to the bonds of connection between human beings in captivity. Once Anthony was moved elsewhere, we may not visit him, inquire about him, or even hear from him. That is one of the great crosses of prison, and the welfare of that person and his soul is something about which we can now only trust. We can only be consoled by what YOU have done in our stead. When I last saw Anthony, he smiled and said, “I have gotten so much mail and so many cards I feel totally surrounded by God’s love.”

Father Michael Gaitley summed up nicely the road out of this dense forest of all our anxious cares:

“So the best way to console Jesus’ Heart is to give him our trust, and according to the expert [Fr Seraphim Michalenko] the best way to live trust is with an attitude of praise and thanksgiving, the way of joyful, trustful acceptance of God’s will.”

Opening Impenetrable Doors

At the end of “Dostoevsky in Prison and the Perils of Odysseus,” I wrote, “the hand of God is somewhere in all this, visible only in the back of the tapestry where we cannot yet see. He is working among the threads, weaving together the story of us.” Some readers liked that imagery, but it’s also true. It really happens and is really happening in our lives right now. I have experienced it, and Pornchai has recently experienced it in a very big way, but only with eyes opened by trust. Here’s how.

In the months after Pornchai Maximilian Moontri and I first met, United States Immigration Judge Leonard Shapiro had just ruled that Pornchai must be deported from the U.S. to Thailand upon whatever point he is to be released from prison. The very thought of this was dismal, like stepping off a cliff in dense fog with no safe landing in sight. Pornchai had only a “Plan B”: to make certain that he never leaves prison.

I was deeply concerned for him, and tried to put myself in his shoes. How does a person get literally dumped into a country only vaguely familiar with no human connections whatsoever? How would he live? How could he even survive? So I told him something so totally foreign to both of us that I shuddered and doubted even as I was saying the words. I told him he has to abandon his “Plan B” and trust. Trust me and trust God. What was I saying?! I wasn’t even sure I trusted at all.

Three years later, Pornchai became a Catholic on Divine Mercy Sunday 2010. A lot of people don’t realize that this was completely by “accident.” And it caused me to worry even more about his future. Thailand is a Buddhist nation. Less than one percent of its people are Catholic. I wondered how becoming Catholic could possibly serve him in a country and culture from which he was already completely alienated and in which he must somehow survive.

Pornchai didn’t even know that the time he was choosing for his entry into the Church was Divine Mercy Sunday. What he had originally planned was to surprise me by telling me of his decision to be Baptized on my birthday, April 9, which was a Friday in 2010. It was, in his mind, to be a birthday present. Some present! I wasn’t even trusting that this was a good idea.

So Pornchai went to talk with the prison’s Catholic chaplain, Deacon Jim Daly to help arrange this. The Chaplain asked a local priest to come to the prison for the Baptism, but he was only available to do this on Saturday, April 10. I stood in as proxy for Pornchai’s Godparents, one in Belgium and one in Indianapolis, while Vincentian Father Anthony Kuzia Baptized and Confirmed Pornchai.

The next day was Divine Mercy Sunday, and it just so happened that Bishop John McCormack was coming to the prison for his annual Mass that day. So just the night before, I explained to Pornchai about Saint Faustina, Divine Mercy, why Pope John Paul II designated the Sunday after Easter to be Divine Mercy Sunday, and how this devotion seemed to sweep the whole world. Pornchai thus received his First Eucharist and was received into the Church on Divine Mercy Sunday, and Whoever planned this, it wasn’t us!

Then because I mentioned that fact on TSW a few times, it got the attention of Felix Carroll, a writer for Marian Helper magazine. Felix then asked if he could write of Pornchai’s Divine Mercy connection for the Marian.org website in an article entitled, “Mercy – Inside Those Stone Walls.” The response to that article was amazing. From all over the world, people commented on it and circulated it. Felix wrote that “the story of Pornchai lit up our website like no other!”

So then in the eleventh hour, Felix Carroll pulled a book he was just about to publish. It was supposed to be about 16 Divine Mercy conversions, but Felix changed the titled to Loved, Lost, Found: 17 Divine Mercy Conversions, and added an expanded chapter about Pornchai Moontri’s life and conversion. The chapter even mentions me and These Stone Walls, though I really had very little to do with Pornchai’s conversion. Pornchai and I received copies of the book, looked at each other, and simultaneously asked, “How did this happen?”

The Needlepoint of God

The book went everywhere, including into the hands of Father Seraphim Michalenko, Director of the National Shrine of The Divine Mercy and the person I quoted on the issue of trust in this post. Father Seraphim became an instrument for the threads God was weaving for Pornchai. He sent the book to another contact, Yela Smit, a co-director of the Divine Mercy Apostolate in Bangkok, Thailand. The result was simply astonishing, and the threads of connection just keep being woven together. I wrote of this incredible account in “Knock and the Door Will Open: Divine Mercy in Bangkok Thailand.”

In that post, I wrote of how I undertook responsibility for easing Pornchai’s burden by trying to find him connections in Thailand only to be frustrated every step of the way. Then, in spite of myself, in the back of the tapestry where we cannot yet see, those threads were being woven together miraculously, and trust found a foundation in the dawn of hope. Suddenly, through nothing either of us did or didn’t do, the cross of fear and dread about how Pornchai would survive alone in Thailand was lifted from him.

Pornchai and I went to Sunday Mass in the Prison Chapel last week. The priest who is usually here is away for a few weeks so we heard it would be someone “filling in.” It was Father Seraphim Michalenko, MIC, 84 years old and the man who opened the doors of Divine Mercy for Pornchai in Thailand where God has accomplished some amazing needlework. Father Seraphim was accompanied by Eric Mahl who also has a chapter in Felix Carroll’s Loved, Lost, Found, and who has become a good friend to me and Pornchai. They both returned that evening for a session of our Consoling the Heart of Jesus Retreat. Pornchai was able to meet with Father Seraphim for a long talk. He has seen firsthand the evidence of Divine Mercy, and it all happened behind the walls of an impenetrable prison.

Behold the Man, as Pilate Washes His Hands

“Ecce Homo!” An 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri depicts a moment woven into the fabric of salvation history, and into our very souls.

“Ecce Homo!” An 1871 painting of Christ before Pilate by Antonio Ciseri depicts a moment woven into the fabric of salvation history, and into our very souls.

“So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd saying, ‘I am innocent of this righteous man’s blood.’”

A now well known Wall Street Journal article, “The Trials of Father MacRae” by Dorothy Rabinowitz (May 10, 2013) had a photograph of me — with hair, no less — being led in chains from my 1994 trial. When I saw that photo, I was drawn back to a vivid scene that I wrote about during Holy Week two years ago in “Dismas, Crucified to the Right: Paradise Lost and Found.” My Holy Week post began with the scene depicted in that photo and all that was to follow on the day I was sent to prison. It was the Feast of Saint Padre Pio, September 23, 1994, but as I stood before Judge Arthur Brennan to hear my condemnation, I was oblivious to that fact.

Had that photo a more panoramic view, you would see two men shuffling in chains ahead of me toward a prison-bound van. They had the misfortune of being surrounded by clicking cameras aimed at me, and reporters jockeying for position to capture the moment to feed “Our Catholic Tabloid Frenzy About Fallen Priests.” That short walk to the prison van seemed so very long. Despite his own chains, one of the two convicts ahead of me joined the small crowd in mockery of me. The other chastised him in my defense.

Writing from prison 18 years later, in Holy Week 2012, I could not help but remember some irony in that scene as I contemplated the fact of “Dismas, Crucified to the Right.” That post ended with the brief exchange between Christ and Dismas from their respective crosses, and the promise of Paradise on the horizon in response to the plea of Dismas: “Remember me when you come into your kingdom.” This conversation from the cross has some surprising meaning beneath its surface. That post might be worth a Good Friday visit this year.

But before the declaration to Dismas from the Crucified Christ — “Today, you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43) — salvation history required a much more ominous declaration. It was that of Pontius Pilate who washed his hands of any responsibility for the Roman execution of the Christ.

Two weeks ago, in “What if the Prodigal Son Had No Father to Return To?”, I wrote of my fascination with etymology, the origins of words and their meanings. There is also a traceable origin for many oft-used phrases such as “I wash my hands of it.” That well-known phrase came down to us through the centuries to renounce responsibility for any number of the injustices incurred by others. The phrase is a direct allusion to the words and actions of Pontius Pilate from the Gospel of Saint Matthew (27: 24).

Before Pilate stood an innocent man, Jesus of Nazareth, about to be whipped and beaten, then crowned with thorns in mockery of his kingship. Pilate had no real fear of the crowd. He had no reason to appease them. No amount of hand washing can cleanse from history the stain that Pilate tried to remove from himself by this symbolic washing of his hands.

This scene became the First Station of the Cross. At the Shrine of Lourdes the scene includes a boy standing behind Pilate with a bowl of water to wash away Pilate’s guilt. My friend, Father George David Byers sent me a photo of it, and a post he once wrote after a pilgrimage to Lourdes:

“Some of you may be familiar with ‘The High Stations’ up on the mountain behind the grotto in Lourdes, France. The larger-than-life bronze statues made vivid the intensity of the injustice that is occurring. In the First Station, Jesus, guarded by Roman soldiers, is depicted as being condemned to death by Pontius Pilate who is about to wash his hands of this unjust judgment. A boy stands at the ready with a bowl and a pitcher of water so as to wash away the guilt from the hands of Pilate . . . Some years ago a terrorist group set off a bomb in front of this scene. The bronze statue of Pontius Pilate was destroyed . . . The water boy is still there, eager to wash our hands of guilt, though such forgiveness is only given from the Cross.”

The Writing on the Wall

As that van left me behind these stone walls that day over thirty years ago, the other two prisoners with me were sent off to the usual Receiving Unit, but something more special awaited me. I was taken to begin a three-month stay in solitary confinement. Every surface of the cell I was in bore the madness of previous occupants. Every square inch of its walls was completely covered in penciled graffiti. At first, it repulsed me. Then, after unending days with nothing to contemplate but my plight and those walls, I began to read. I read every scribbled thought, every scrawled expletive, every plea for mercy and deliverance. I read them a hundred times over before I emerged from that tomb three months later, still sane. Or so I thought.

When I read “On the Day of Padre Pio, My Best Friend Was Stigmatized,” Pornchai Maximilian Moontri’s guest post from Thailand, I wondered how he endured solitary confinement that stretched for year upon year. “Today as I look back,” he wrote, “I see that even then in the darkness of solitary confinement, Christ was calling me out of the dark.” It’s an ironic image because one of the most maddening things about solitary confinement is that it’s never dark. Intense overhead lights are on 24/7.

The darkness of solitary confinement he described is only on the inside, the inside of a mind and soul, and it’s a pitch blackness that defies description. My psyche was wounded, at best, after three months. I cannot describe how Pornchai endured this for many years. But he did, and no doubt those who brought it about have since washed their hands of it.

For me, once out of solitary confinement, the writing on the walls took on new meaning. In “Angelic Justice: St Michael the Archangel and the Scales of Hesed,” I described a section of each cell wall where prisoners are allowed to post the images that give meaning and hope to their lives. One wall in each cell contains two painted rectangles, each barely more than two by four feet, and posted within them are the sole remnant of any individualism in prison. You can learn a lot about a man from that finite space on his wall.

When I was moved into this cell, Pornchai’s wall was empty, and mine remained empty as well. Once this blog began in 2009, however, readers began to transform our wall without realizing it. Images sent to me made their way onto the wall, and some of the really nice ones somehow mysteriously migrated over to Pornchai’s wall. A very nice Saint Michael icon spread its wings and flew over to his side one day. That now famous photo of Pope Francis with a lamb placed on his shoulders is on Pornchai’s wall, and when I asked him how my Saint Padre Pio icon managed to get over there, he muttered something about bilocation.

Ecce Homo!

One powerful image, however, has never left its designated spot in the very center of my wall. It’s a five-by-seven inch card bearing the 1871 painting, “Ecce Homo!” — “Behold the Man!” — by the Swiss-born Italian artist, Antonio Ciseri. It was sent to me by a reader during Holy Week a few years ago. The haunting image went quickly onto my cell wall where it has remained since. The Ciseri painting depicts a scene that both draws me in and repels me at the same time.

On one dark day in prison, I decided to take it down from my wall because it troubles me. But I could not, and it took some time to figure out why. This scene of Christ before Pilate captures an event described vividly in the Gospel of Saint John (19:1-5). Pilate, unable to reason with the crowd has Jesus taken behind the scenes to be stripped and scourged, a mocking crown of thorns thrust upon his head. The image makes me not want to look, but then once I do look, I have a hard time looking away.

When he is returned to Pilate, as the scene depicts, the hands of Christ are bound behind his back, a scarlet garment in further mockery of his kingship is stripped from him down to his waist. His eyes are cast to the floor as Pilate, in fine white robes, gestures to Christ with his left hand to incite the crowd into a final decision that he has the power to overrule, but won’t. “Behold the Man!” Pilate shouts in a last vain gesture that perhaps this beating and public humiliation might be enough for them. It isn’t.

I don’t want to look, and I can’t look away because I once stood in that spot, half naked before Pilate in a trial-by-mob. On that day when I arrived in prison, before I was thrown into solitary confinement for three months, I was unceremoniously doused with a delousing agent, and then forced to stand naked while surrounded by men in riot gear, Pilate’s guards mocking not so much what they thought was my crime, but my priesthood. They pointed at me and laughed, invited me to give them an excuse for my own scourging, and then finally, when the mob was appeased, they left me in the tomb they prepared, the tomb of solitary confinement. Many would today deny that such a scene ever took place, but it did. It was thirty years ago. Most are gone now, collecting state pensions for their years of public service, having long since washed their hands of all that ever happened in prison.

Behold the Man!

I don’t tell this story because I equate myself with Christ. It’s just the opposite. In each Holy Week post I’ve written, I find that I am some other character in this scene. I’ve been “Simon of Cyrene, Compelled to Carry the Cross.” I’ve been “Dismas, Crucified to the Right.” I tell this story first because it’s the truth, and second because having lived it, I today look upon that scene of Christ before Pilate on my wall, and I see it differently than most of you might. I relate to it perhaps a bit more than I would had I myself never stood before Pilate.

Having stared for three years at this scene fixed upon my cell wall, words cannot describe the sheer force of awe and irony I felt when someone sent me an October 2013 article by Carlos Caso-Rosendi written and published in Buenos Aires, Argentina, the home town of Pope Francis. The article was entitled, “Behold the Man!” and it was about my trial and imprisonment. Having no idea whatsoever of the images upon my cell wall, Carlos Caso-Rosendi’s article began with this very same image: Antonio Ciseri’s 1871 painting, “Ecce Homo!” TSW reader, Bea Pires, printed Carlos’ article and sent it to Pope Francis.

I read the above paragraphs to Pornchai-Maximilian about the power of this scene on my wall. He agrees that he, too, finds this image over on my side of this cell to be vaguely troubling and disconcerting, and for the same reasons I do. He has also lived the humiliation the scene depicts, and because of that he relates to the scene as I do, with both reverence and revulsion. “That’s why it stay on your wall,” he said, “and never found its way over to mine!”

Aha! A confession!

+ + +

Note from the Editor: Please visit our Holy Week Posts Page.

Coming Home to the Catholic Faith I Left Behind

Former police Sgt Michael Ciresi lost his faith and left his Church after a devastating childhood trauma. His coming home is the moving story of a prodigal son.

Former police Sgt Michael Ciresi lost his faith and left his Church after a devastating childhood trauma. His coming home is the moving story of a prodigal son.

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Michael Ciresi, a former North Providence, RI police sergeant now writing from the NH State Prison.

On Sunday, March 30, 2014, I took part in a Consecration to Mary during Mass in the Chapel of the New Hampshire State Prison. It was the end of my “33 Days to Morning Glory” retreat, the second such retreat to be offered in this prison, and it began a new chapter in my life. A door has opened that was slammed shut long ago, and for me it is miraculous.

I am 46 years old, and over the last year I have returned to the Catholic faith I left behind 36 years ago. My two good friends in this prison, Gordon MacRae (Father G) and Pornchai Moontri were invited to take part in the “33 Days to Morning Glory” retreat last October. I wanted to sign up with them, but only because they are my friends. I had no religious reason for doing this at the time. You may have read (see “Woman, Behold Your Son!“) that Father G and Pornchai decided not to go because of some very trying times in this prison. I remember that month, and all they had been through. I wish I could spell it out to you, but I cannot.

In the end, they took part in the “33 Days,” (see “Behold Your Mother!”) but I lost my spot because of their indecision. No harm, no foul, I thought. I didn’t really want to go anyway, or so I believed. Then an opportunity for a second “33 Days” retreat rolled around and Gordon and Pornchai decided I was going. Well, I wasn’t! And I thought that was final! It’s enough they drag me to Mass on Sunday, something I would not have seen myself ever doing just two years ago. Then on one of those Sunday mornings at Mass while sitting next to my two good friends, I took out a photo of my 11-year-old twin sons, Michael, Jr. and Steven.

I nudged Father G. to show him the photo. He looked, and then whispered, “Someday your sons might need your faith. You’d better have some when that day comes.” That did it! I conceded defeat to my worthy adversary and signed up for the second “33 Days to Morning Glory” on my way out of Mass that morning.

Our friend, Michael Martinez signed up with me. This all makes for a very strange story with connections from the past that Father G wrote about in “With the Dawn Comes Rejoicing: Lent for the Lost and Found.” As Michael Martinez and I stood at Mass on March 30 for our Consecration, I realized that G’s title for that post was perfect. It was the dawn for us, and we had much to rejoice about. The road up to that point is long and painful and I have been invited by Father G to tell you about it.

To Serve and Protect

For as long as I can remember, all I ever wanted to be in life was a police officer. I still remember the day a police officer from my home town of Providence, Rhode Island visited our grade school with his black and white cruiser. All the kids in my class were wide-eyed at the sight of the officer in his sharp uniform with his badge and hardware. He wore a handgun low on his hip and his hat stood tall on his head. In my mind as a child, he was a modern day cowboy.

I was spellbound as the officer spoke about his job description, “to serve and protect your families and our community.” He turned to me and asked my name. “Michael, sir,” I said. “Well, Michael, how would you like to see the inside of the cruiser?” I was the luckiest kid on earth! In full view of my classmates, I hopped into the driver’s seat and he placed his hat on my head. It fell over my eyes and I had to prop it at an angle to see. He then showed me how to work the lights and siren and said, “You should consider being a police officer when you grow up.” At eight years old, my life’s path was laid out clearly before me.

Fast forward 13 years. I was a proud graduate of the Rhode Island Police Academy in its Class of 1989. My mother was in attendance, and she proudly pinned my first shield — Badge 83 — on my uniform. I told my mother no one could ever hurt us or our family as long as I wear that uniform. This was a job that commanded respect, but it also commanded power and control, two factors that past events made very important to me. They would come back to haunt me, but I’ll get back to that.

My mother was a devout Catholic who raised all six of her children in a strict Catholic tradition. After my childhood school experience with the visiting police officer and his black and white cruiser, I became an altar server for a brief period of time. The proudest moment of my childhood — even more so than sitting behind the wheel of that cruiser — was the first time I served at Mass. It seems so very long ago now — a lifetime ago.

The Fall of Man

I have harbored a dark secret for a long time, and it was because of this secret, I know today, that I had great difficulty surrendering control or ever appearing vulnerable in my life. As a young child, I was by nature very trusting. I believed that most people were good, and I had immense faith in the Lord that no one would ever harm me. This all changed in the summer after my ninth birthday.

I cannot go into the details of what happened, for the details are not the story I wish to tell. At the age of nine, I became a victim of sexual abuse. The perpetrator was someone I trusted implicitly, and never for a moment questioned being alone with. I saw him as a friend, and as one of the sources of my naive childhood sense of safety and security. He was one of our local Catholic priests. I lost many things that day, and first among them was all sense of power and control over my life. That loss would influence me and my actions from that day forward.

My immediate reaction was to quit as an altar server to the great chagrin of my devout mother. I could never tell her what had happened to me. From that day forward, we argued constantly about attending Mass. On one Sunday in particular, I was so filled with anxiety and shame that I hid from my family to avoid going to Mass with them. I was terrified, and no child should ever equate God or the Church or faith with terror. I hid, and that triggered a large search party, including local police, that spent most of that Sunday looking for me. No one in my family ever knew what really happened. They never knew the nightmare I was living in.

Over the following years of my childhood, I pulled completely away from anything to do with faith and my Church. The final nail in God’s coffin for me was the death of my mother from cancer at age 54, just months after she pinned on my badge at the Police Academy.

Even in the last days of her life, my mother tried to assure me that God was always there, always watching over me, and would always protect me. Once she was gone, I buried God and the Church with her, and took control of my own life and destiny. I thought no one could ever take anything from me again.

The Right to Remain Silent

Throughout my career as a police officer, I also buried my childhood nightmare not even realizing that I was living it out by exacting vengeance upon anyone who abused others through sex or violence. With each event, I fell deeper and deeper into a spiritual abyss. I had an illustrious two-decade career with many high profile arrests, numerous commendations and letters of recognition. That was on the outside, but on the inside I always struggled with a fear of losing power and control. There were times when I placed myself in harm’s way, times when I could have been killed, even times when I wished I had. I was not aware of my downward spiral as an officer and as a man. Then the bottom fell out beneath me.

By 2004, after 15 years on the force, my life started to visibly unravel. I was having marital problems, family issues, financial challenges, and my attempts to control everything made them worse. Instead of seeking help, which would mean surrendering control, I continued down this path of destruction leading a double life as a police officer. I was indicted and faced trial, and then convicted, for robbing two notorious drug dealers. I was made an example of, and sentenced to twenty years in prison — almost the same amount of time I had been a police officer.

On May 29, 2008 I entered prison to face what I was sure would be a death sentence. I was filled with hate, anger, disgust, and loneliness in the three months I spent in solitary confinement. Then I was transferred to the New Hampshire State Prison where I could leave my past behind and no one would ever know of my prior life as a decorated police officer. I started life in this new prison alone, afraid, filled with anger and hate and for all of it, I shared the blame equally between myself and God.

The worst part of it was that I knew there was no one I could ever trust. I was wrong about that. I was wrong about a lot of things. In prison I was moved again and again, always kept in a state of adjustment, until early 2009 when I landed in a unit that housed two men who were to become the best friends I have ever known.

I first met Pornchai Moontri when I made it known that I wanted to join a weekend prisoner card game. I was determined not even to tell other prisoners my name, so they just called me random names, whatever came to mind. Then in the middle of a card game, Pornchai Moontri said something shocking. He said, “You remind me of ‘Hank,’ that Rhode Island State Trooper played by Jim Carey in that movie, ‘Me, Myself, and Irene!’ ”

I was stunned! Did he know? It turned out he didn’t, but from that day on I was stuck with the prison moniker, “Hank” and that is what Pornchai and others, including Father G, call me to this day. Later, I came to know Pornchai, and though I was still very guarded about my past, I came to some degree of trust for him. He often spoke of his roommate, Gordon, and how he had helped Pornchai change the course of his life. When Pornchai told me Gordon is a Catholic priest, however, I felt the blood freeze in my veins. I would have nothing to do with him. I spoke only when I had to. I despised him for what he was.

As I came to know Pornchai, however, there was no avoiding interacting with his friend, Gordon. The trust between them was highly visible, and so unusual not only in my life, but in prison. I slowly came to confide in Pornchai about my life, including my life as a police officer. Gordon was part of some of those conversations. They just quietly accepted me, and even protected me by keeping this news from others. I slowly began to challenge the limits of my trust.

Then one day I risked talking with Gordon alone. I asked straightforward questions about his life and how he came to prison, and much of what I heard troubled me. I told him that I had lots of questions about the case against him, about the way it was investigated and all that happened. Today, I am absolutely convinced that he was and is a victim of false accusation for monetary gain. I have lots of unanswered questions about the behavior of the police detective who seemed to orchestrate this case.

But throughout all that, Gordon was really the one doing all the probing. He got so much out of me without my even realizing it that one day he sat me down alone and said, “Michael, there is something more, and I know what it is.” I denied it. Then Gordon asked Pornchai if he would let me read “Pornchai’s Story.” Pornchai agreed.

I was stunned! I was completely blown away! I was stunned not only by the awful secret I shared with Pornchai in our respective childhoods, but also by the huge transformation in Pornchai’s life when his devastating secret was stripped of its power. He shared his secret with Father G, and then, through “Pornchai’s Story,” with the world.

So I plunged into my abyss. I told Father Gordon everything. The three of us had long talks about what happened, and what it means for my life as a man, as a father, as a friend, as a Catholic. The secret I had kept all those years, that terrible burden of shame and anxiety, is now just a chapter in an open book that is my new life. And as it all came out, my anger with God somehow was also transformed. I followed the lead of my two friends, and they led me into the light of Divine Mercy.

I am a work in progress. I know that. But I have found two friends who I today know are gifts from God sent to show me the way back, not only to faith but to the people who mean the most to me in this world, my sons Michael, Jr. and Steven whom I hold deep in my heart and soul. Father G was right! Faith is the most precious gift I can ever share with my sons, and I must share it the same way it was shared with me: by example — by the heroic example of wounded men who are true believers and who place even their wounds in the service of Christ their King!

In my Marian Consecration after “33 Days to Morning Glory” last week, I placed myself in the rays of Divine Mercy coming from the Heart of our Lord. I will never be able to understand and explain the strangeness of it all, but in prison, with the very best of friends and teachers, I am learning how to be free.

+ + +

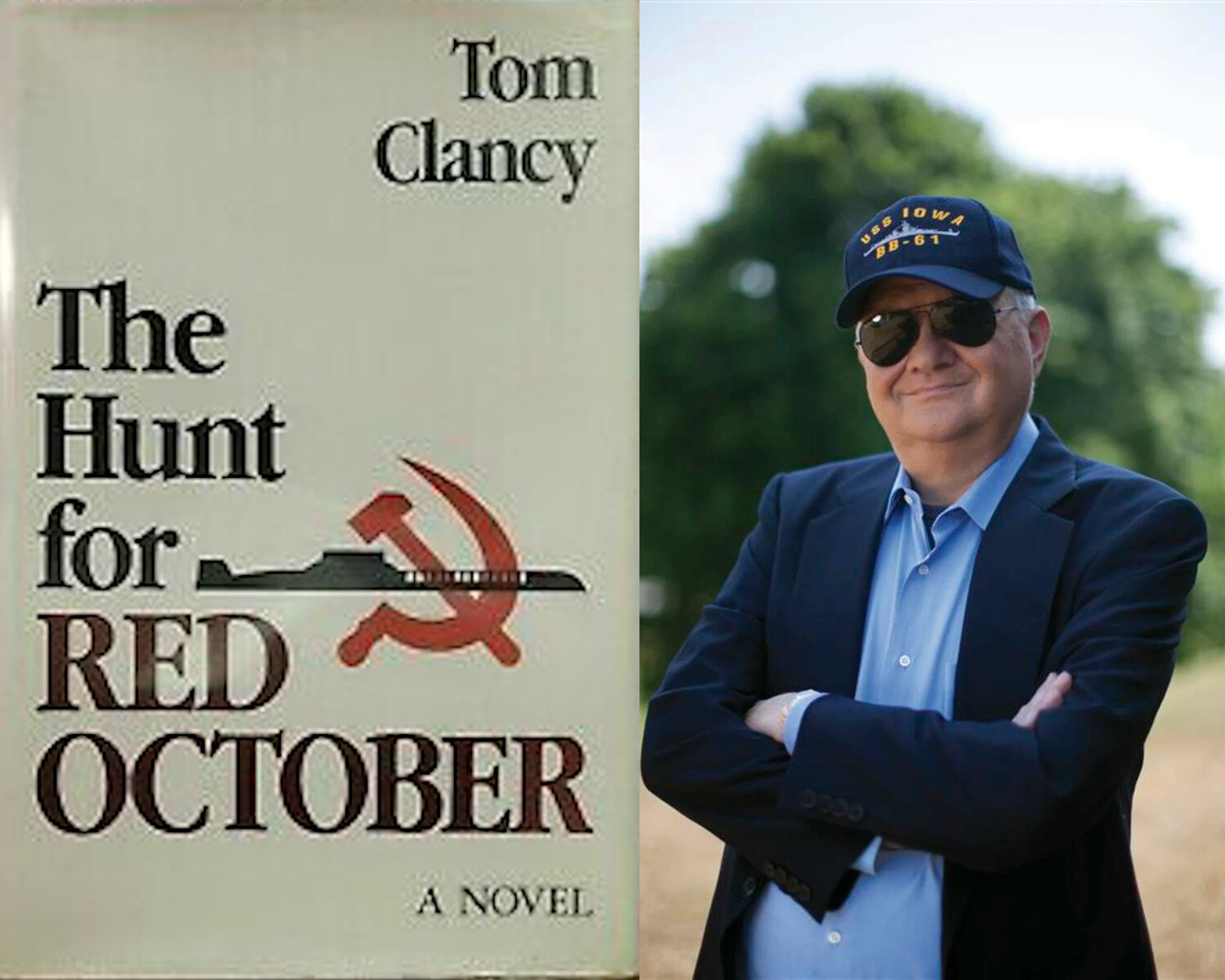

Tom Clancy, Jack Ryan, and The Hunt for Red October

Novelist Tom Clancy, master of the techno-thriller, died on October 1st. His debut Cold War novel, The Hunt for Red October, was an American literary landmark

Novelist Tom Clancy, master of the techno-thriller, died on October 1st. His debut Cold War novel, The Hunt for Red October, was an American literary landmark.

In 2011 at Beyond These Stone Walls, I wrote a post for All Souls Day entitled “The Holy Longing: An All Souls Day Spark for Broken Hearts.” Some readers who have lost loved ones very dear to them found solace in its depiction of death as a continuation of all that binds human hearts and souls together in life. Like all of you, I have lost people whose departure left a great void in my life.

It’s rare that such a void is left by someone I knew only through books, but news of the death of writer, Tom Clancy at age 66 on October 1st left such a void. I cannot let All Souls Day pass without recalling the nearly three decades I’ve spent in the company of Tom Clancy.

I’ll never forget the day we “met.” It was Christmas Eve, 1984. Due to a sudden illness, I stood in for another priest at a 4:00 PM Christmas Eve Mass at Saint Bernard Parish in Keene, New Hampshire. I had no homily prepared, but the noise of a church filled with excited children and frazzled parents conspired against one anyway. So I decided in my impromptu homily to at least try to get a few points of order across.

Standing in the body of the church with a microphone in hand I began with a question: “Who can tell me why children should always be quiet and still during the homily at Mass?” One hand shot up in the front, so I held the microphone out to a little girl in the first pew. Proudly standing up, she put her finger to her lips and whispered loudly into the mic, “BECAUSE PEOPLE ARE SLEEPIN’!”

Of course, it brought the house down and earned that little girl — who today would be about 38 years old — a rousing round of applause from the parishioners of Saint Bernard’s. It lessened the tension a bit from what had been a tough year for me in that parish.

But that’s not really the moment I’ll never forget. After that Mass, a teenager from the parish walked into the Sacristy to hand me a hastily wrapped gift. In fact, it looked as though he wrapped it during the homily! “We’re not ALL sleeping,” he said about the little girl’s remark. I laughed, and when it was clear that he wasn’t leaving in any hurry, I asked whether he wanted me to open his gift. He did. I joked about needing bolt cutters to get through all the tape. It was a book. It was Tom Clancy’s The Hunt for Red October. “Oh, wow!” I said. “How did you know I’ve been wanting to read this?”

It was a lie. I admit it. But it was a white lie. It was the sort of lie one tells to spare the feelings of someone who gives you a book you’ve never heard of and had no plan to read. I remember hearing about a circa 1980 interview of Barbara Walters with “Miss Lillian,” a Grand Dame of the U.S. South and the mother of then President Jimmy Carter. Miss Lillian — to the chagrin of presidential handlers — declared that her son, the President, “has nevah told a lie.”

“Never?!” prodded Barbara Walters. “Well, perhaps just a white lie,” Miss Lillian hastily added. “Can you give us an example of a white lie?” asked Barbara Walters. After a thoughtful pause, Miss Lillian looked her in the eye and reportedly said in her pronounced Southern drawl, “Do you remembah backstage when Ah said you look really naace in thaat dress?” Barbara was speechless! First time ever!

Mine was that sort of lie. The young giver of that gift would be about 43 years old today, and if he is reading this I want to apologize for my white lie. Then I also want to tell him that his gift changed the course of my life with books. I had read somewhere that First Lady Nancy Reagan also gave that book as a gift that Christmas. True to his penchant for adding new words to the modern American English lexicon, President Ronald Reagan declared The Hunt for Red October to be “unputdownable!”

So after a few weeks collecting dust on my office bookshelf I took The Hunt for Red October down from the shelf and opened its pages late one winter night.

“Who the Hell Cleared This?”

After busy days I have a habit of reading late at night, a habit that began almost 30 years ago with this gift of Tom Clancy’s first novel. Parishioners commented that they drove down Keene’s Main Street at night to see the lights on in my office, and “poor Father burning midnight oil at his desk.” I was doing nothing of the sort. I was submersed in The Hunt for Red October, at sea in an astonishing story of courage and patriotism.

In the early 1980s, the Cold War was freezing over again. The race to develop a “Star Wars” defense against nuclear Armageddon dominated the news. President Ronald Reagan had thrown down the gauntlet, calling the Soviet Union an “Evil Empire.” Pope John Paul II was working diligently to dismantle the Soviet machine in Poland. The Soviet KGB was suspected of being behind an almost deadly attempt to assassinate the pope. It was an event that later formed yet another powerful and stunning — and ultimately true — Tom Clancy/Jack Ryan thriller, Red Rabbit.

In the midst of this glacial stand-off between superpowers that peaked in 1984, Tom Clancy published The Hunt for Red October. Its plot gripped me from page one. The Soviets launched the maiden voyage of their newest, coolest Cold War weapon, a massive, silent, and virtually undetectable ballistic nuclear missile submarine called “Red October.” Before embarking, the Red October’s Captain, the secretly renegade Marko Ramius, mailed a letter to his Kremlin superiors indicating his intent to defect and hand over the prized sub’s technology and nuclear arsenal to the government of the United States.

By the time the Red October departed the Barents Sea for the North Atlantic, the entire Soviet fleet had been deployed to hunt her down and destroy her. American military intelligence knew only that the Soviets had launched a massive Naval offensive. An alarmed U.S. Naval fleet deployed to meet them in the North Atlantic, bringing Cold War paranoia to the brink of World War III and nuclear annihilation.

Having few options in the book, the Soviets fabricated to U.S. intelligence a story that they were attempting to intercept a madman, a rogue captain intent on launching a nuclear strike against America. Captain Marko Ramius and the Red October were thus hunted across the Atlantic by the combined Naval forces of the world’s two great superpowers operating in tandem, and in panic mode, but for different reasons.

Then the world met Jack Ryan, a somewhat geeky, self-effacing Irish Catholic C.I.A. analyst and historian. Ryan, with an investigator’s eye for detail, had studied Soviet Naval policies and what files could be obtained on its personnel. Jack Ryan alone concluded that Captain Marko Ramius was not heading for the U.S. to launch nuclear missiles, but to defect. Ryan had to devise a plan to thwart his own country’s Navy, and simultaneously that of the Soviet Union, to bring the defector and his massive submarine into safe harbor undetected.

In the telling of this tale, Tom Clancy nearly got himself into a world of trouble. His understanding of U.S. Navy submarine tactics and weapons technology was so intricately detailed that he was suspected of dabbling in leaked and highly classified documents. When Navy Secretary, John Lehman read the book, he famously shouted, “WHO THE HELL CLEARED THIS?”

The truth is that Tom Clancy was an insurance salesman whose handicap — his acute nearsightedness — kept him out of the Navy. He wrote The Hunt for Red October on an IBM typewriter with notes he collected from his research in the public records of military technology and history available in public libraries and published manuals. His previous writing included only a brief article or two in technical publications.

The Hunt for Red October was so accurately detailed that its publishing rights were purchased by the Naval Institute Press for $5,000. Clancy hoped that it might sell enough copies to cover what he was paid for it. It became the Naval Institute’s first and only published novel, and then it became a phenomenal best seller — thanks in part to President Reagan’s declaration that it was “unputdownable.” And it was! It was also — at 387 pages — the smallest of 23 novels yet to come in a series about Clancy’s hero — and alter ego — Jack Ryan.

The World through the Eyes of Jack Ryan

After devouring The Hunt for Red October in 1984, for the next 25 years — and nearly 17,000 pages of a dozen techno-thrillers — I was privileged to see the world and its political history through the eyes of Tom Clancy’s great protagonist, Jack Ryan.

From that submarine hunt through the North Atlantic, Tom Clancy took us to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in The Cardinal of the Kremlin, the Irish Republican Army’s terrorist branches in Patriot Games, the drug cartels of Colombia in Clear and Present Danger, and the threat of domestic terrorism in The Sum of All Fears. This list goes on for another seven titles in the Jack Ryan series alone as the length of Tom Clancy’s stories grew book by book to the 1,028-page tome, The Bear and the Dragon, all published by Putnam. I wrote of Tom Clancy again, and of his gift for analyzing and predicting world events, in one of the most important posts on BTSW, “Hitler’s Pope, Nazi Crimes, and The New York Times.”

At the time of Tom Clancy’s death at age 66 on October 1st, he had amassed a literary franchise with 100 million books in print, seven titles that rose to number one on best seller lists, $787 million in box office revenues for film adaptations, and five films featuring his main character, Jack Ryan, successively portrayed by Alec Baldwin, Harrison Ford, Ben Affleck, and Chris Pine (the latter, and his final book, due out in December 2013).

I once made the chauvinistic mistake of calling Tom Clancy’s novels “guy books.” Mea culpa! It isn’t so, and I was divested of that view by several women I know who love his books. Writing in USA Today (“Tom Clancy wrote America well,” October 9) Laura Kenna wrote of Tom Clancy’s sure-footed patriotism as America stood firm against the multitude of clear and present dangers:

“We will miss Tom Clancy, his page-turning prose and the obsessive attention to detail that brought the texture of reality to his books. We have already been missing the political universe from which Clancy came and to which his books promised to transport us, a place never simple, but still certain, where clear convictions made flawed Americans into heroes.”

Tom Clancy was himself a flawed American hero whose nearsighted handicap was in stark contrast to the clarity and certainty of vision that he gave to Jack Ryan, and to America. I think, today, Clancy might write of a new Cold War, not the one about nuclear warheads pointing at America, but the one about Americans pointing at each other. He might today write of a nation grown heavy and weary with debt and entitlement.

As Tom Clancy slipped from this world on October 1, 2013, his country submerged itself into a sea of darker, murkier politics, those of a nation still naively singing the Blues while the Red October slips quietly away.

Mother’s Day Promises to Keep, and Miles to Go Before I Sleep

Honoring Mom on Mother's Day brought me to Robert Frost's most famous poem and its deepest meaning about life, loss, and hope.

Honoring Mom on Mother’s Day brought me to Robert Frost’s most famous poem and its deepest meaning about life, loss, and hope.

You may remember a post I wrote a few years ago entitled “A Corner of the Veil.” It was about my mother, Sophie Kavanagh MacRae, who died on November 5, 2006 during my 12th year in prison. That hasn’t stopped her from visiting, however. I had a strange dream about her a few nights ago, and I keep going back to it trying to find some meaning that at first eluded me.

The United Kingdom celebrates Mothering Sunday on the Fourth Sunday of Lent, but in North America, Mother’s Day is on the second Sunday of May. I wonder if that was what prompted my vivid dream. It was in three dimensions, sort of like looking through one of those stereoscopic View Masters we had long ago. Pop in a disk of images and there they were in three dimensions and living color. My dream was like that, even the color — which is strange because I am colorblind since birth. My rods and cones are just not up to snuff, and though I do see some color, my view of the world is, I am told, not far afield from basic black and white and many shades of gray. Priesthood saved me from a lifetime of wondering why people grimace at my unmatched clothes.

Back to my dream. I was standing on Empire Street in Lynn, Massachusetts, in front of the urban home where I grew up. My mother was standing with me, but in the dream, as in today’s reality, we could not go inside that house because neither of us lived there any longer. My dream contained overlapping realities. It was clear to me that my mother had died, but there she was. And it was clear to me that I am in prison, but there I was with her on that street in front of the home I left forty years ago.

The scene was the stuff of dreams, and it strikes me now that this dream was a reminder of something essential, some truth I could easily let slip away, but must not. I once wrote of that house and that street in an early TSW post called “February Tales.” I wrote of the books that captivated me in childhood, books that I read for hours on end perched high in the treetops along our city street. To this day I can hear my mother calling out a window in her Newfoundland brogue, “IF YOU FALL OUT OF THAT BLOODY TREE AND BREAK YER LEG, DOEN’T COME ARUNNIN’ TO ME!”

As my mother and I crossed the street away from that house in my dream, we spoke, but nothing of that conversation survived in my consciousness except one sentence, and it was perplexing. I said, as I kissed her good-bye, “I have promises to keep.” With a pack over my shoulder in my dream, I turned away to walk toward the end of our city street. In my youth, there was a bus stop there where I could board a bus that would take me the ten miles to Logan Airport or on to Boston’s North Station. From there, I could go anywhere. As I walked down the street in the last scene of my dream, I looked back to see my mother waving. I was leaving. I was always leaving.

You may recognize my final words to my mother in the dream. They are a line from a famous, multi-layered and haunting poem by the great Robert Frost entitled “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” Here it is:

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village, though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

A Life and Death Conversation

I say this poem is multi-layered because all by itself, with no search at all for deeper meaning, it tells a nicely unadorned tale on its surface. However, I believe Robert Frost packed this little verse with profound meaning about life and death. For me, the owner of the woods who lives in the village is God, the Author of Life, our Redeemer from death, and One who calls us to a task that gives meaning to our lives — even when we have no idea what that meaning is just yet. Even when we do not even know the task to which we are called.

There is something haunting and alluring about stopping by woods on a snowy evening. If you have ever stood in the woods at night while it snows, then you know the awesome, mesmerizing silence of that experience. All sound is absorbed, and the powerful sense of aloneness can produce inner peace. But it can also trigger a sense of foreboding, of being cut off from the sounds and sights of humanity, cut off from life in the village. Today’s fear of death is, in its essence, a fear of utter silence, of the world of no more.

Even the poem’s “little horse” is a symbol of the simplicity of our animal nature. The horse ponders not the meaning of the woods, and “gives his harness bells a shake” to bring his rider back to his senses. “We’ve no reason to stop here.” The horse knows nothing of his rider’s yearning for surrender, for a time of removal from the civilization and social responsibility in which the Owner of those woods is engaged in the village ahead.

It’s okay to stop by the woods on a snowy evening. We just can’t stay there. Not yet. Robert Frost’s woods represent death. “The woods are lovely, dark, and deep,” and they stand in the poem as an invitation to final surrender and rest. “Sleep” in the poem is a metaphor for death, just as it is for Jesus as he awakens Lazarus from the sleep of death:

“‘Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I go to awake him out of sleep.’ The disciples said to him, ‘Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will recover.’ Now Jesus had spoken of his death, but they thought that he meant taking rest in sleep. Then Jesus told them plainly, ‘Lazarus is dead; and for your sake I am glad that I was not there, so that you may believe. But let us go to him.’ Thomas, called the Twin, said to his fellow disciples, ‘Let us also go, that we too may die with him.’”

— John 11: 11-16

If you have read this far, and my analysis of Robert Frost’s poem hasn’t put you to sleep, then like me you might wonder what exactly I meant when I whispered to my mother that “I have promises to keep.” The dream didn’t spell it out for me, so I had to search for its deeper meaning.

In our poem, the rider seems to be on a journey, though Frost gives us no indication of its purpose or destination. At the end of his journey, the rider has “promises to keep” but the woods, “lovely, dark, and deep” are an enticing release from both the journey and his burdens. But the responsibility of his promises pulls harder than the woods, and his release — his inevitable death — is postponed. The rider moves on toward his destiny and the fulfillment of his promises — both those he has made and those made to him. He moves on, as I did in the dream of my mother, with “miles to go before I sleep.”

The Promise

My mother died a terrible death, having suffered for three years from hydrocephalus, the build-up of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. It was misdiagnosed in her early seventies, and by the time it was properly diagnosed, it could not be treated. She visited me in prison with a cane, and then a walker, and then a wheelchair, and then, for the last year of her life, not at all. Though only sixty miles away from my prison, she could not even speak with me by telephone for the last six months of her life. She became paralyzed, and entered a prison of her own.

In our last visit in the New Hampshire State Prison visiting room a year before my mother died, I told her I was sorry for what had become of my life and my priesthood. Most mothers of priests — especially Irish mothers — take a certain pride in the priesthood of their sons. My mother left this world with her own priest-son in prison. I worried about the wounds to her pride my false imprisonment wrought.

But all was not lost. There was grace even in that. Sometime near Mother’s Day I hope you might read anew — or for the first time — “A Corner of the Veil.” It describes a promise I made to my mother that I would never take the easy way out of the crisis to which priesthood brought me. I intend to keep that promise, and in a dream last week, my mother showed up to help strengthen its resolve. But more than that, “A Corner of the Veil” is about the continuity of relationship between the living and the dead. That post described a very subtle but deeply meaningful connection with my mother beyond this life, and I might have missed it if I let the growing spiritual cynicism of this world take root in prison and take my faith as it grew and festered.

What I described in that post is a true tale, and a powerful one, and I haven’t yet recovered from the nudge — a smack upside the head, really — from my mother. It was her wake-up call to me to stop by the woods on a snowy evening just long enough to peer through a corner of the veil between this life and the next, and to renew my engagement with both the mysteries and promises of my faith despite where I must, for this moment, live it.

I have heard from so many readers Beyond These Stone Walls asking me for prayers for their mothers, living and dead, some beloved and some estranged, some deeply missed and some slowly leaving this world. On Mother’s Day I promise, the Owner willing, to offer Mass for all the readers of Beyond These Stone Walls who are mothers, and for all of your mothers. Those who have passed from this life are, I think, also reading, and they can hold me to it. Perhaps they’ll gather. Perhaps they’ll even plot. Were that the case, my mother would surely be in Heaven!

We, the living, have promises to keep, and miles to go before we sleep. First among those promises is to engage in a vibrant life of faith that opens itself to the continuity of life between this world and the next, something our culture of death denies. Fostering that faith, and making fertile its ground, is a great responsibility, and the source of all freedom. That’s the absolute truth! Just ask Mom!

“And he said to them, ‘How is it that you sought me? Did you not know that I must be in my Father’s house?’ And they did not understand the saying which he spoke to them. And he went down with them and came to Nazareth, and was obedient to them; and his mother kept all these things within her heart.”

— Luke 2: 49-51