“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

The Pillar; Msgr Jeffrey Burrill; Blackmail of the Vatican

A story of one U.S. priest and his moral fall from grace has spun into accusations of a witch hunt and international suspicions of Chinese blackmail of the Vatican.

A story of one U.S. priest and his moral fall from grace has spun into accusations of a witch hunt and international suspicions of Chinese blackmail of the Vatican.

August 18, 2021

After just weeks ago posting “Our Tabloid Frenzy About Fallen Priests,” I have been highly resistant to stepping into this one. In a matter of weeks, this story has grown so many tentacles that I am not even certain of where to begin. My goal is not to join the frenzy, but rather to perhaps bring a little perspective to it. So I will begin where no one else has begun.

For the last year, Msgr Jeffrey Burrill had been in the high profile and highly prestigious position of General Secretary of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. For the preceding four years he served in the position of Associate General Secretary. He has been referred to as the highest ranking member of the U.S. Catholic clergy who is not a bishop. I do not have a defense of Msgr Burrill except to say that his life and priesthood have been shredded in recent weeks. Perhaps this is even right and just, but a Church should not settle for leaving the story there. I hope and pray for an avenue of repentance and restoration.

But first, the tabloid frenzy: The story is complicated. A new Catholic media venue called The Pillar published an investigative report on July 20, 2021 that resulted in the abrupt resignation of Msgr Burrill from his position in the leadership of the USCCB. It also ignited a firestorm of debate about journalistic ethics, priestly celibacy and homosexuality, and the difference between private behavior and public crimes. To date, Msgr Burrill stands accused of no crimes, but The Pillar report alleging promiscuous homosexual behavior left his career in ruins.

The Pillar, founded just eight months ago, is staffed by former Catholic News Agency editor J. D. Flynn and former CNA reporter, Ed Condon. Using and doggedly cross-referencing easily accessible data from a homosexual “hook-up” app called Grindr, the two journalists were able to pinpoint “emitted app data signals” from Grindr to a specific device “on a near daily basis during parts of 2018, 2019, and 2020” according to The Pillar report. The device belongs to Msgr Jeffrey Burrill and was allegedly used for the purpose of anonymous sexual encounters from his USCCB office and residence as well as in other cities, sometimes while handling USCCB affairs.

The journalists sought comment from Msgr Burrill and the USCCB leadership before breaking this story. A meeting was scheduled, then cancelled. Msgr Burrill resigned from his position as USCCB General Secretary on July 19, a day before the 3,000 word story was published by The Pillar under the title: “Pillar Investigates: USCCB Gen Sec Burrill Resigns After Sexual Misconduct Allegations.”

Almost immediately, apologists for the gay agenda went into action. The National Catholic Reporter (please be clear that we are not talking about the NC Register) accused The Pillar of operating on “a shaky journalistic foundation.” (Coming from NCR, I found that to be most ironic.) Jesuit Father James Martin accused The Pillar of using “immoral tactics” to “out” Msgr Burrill. Writing for The Wall Street Journal, Deputy Editorial Features Editor Matthew Hennessey wrote an outstanding defense of The Pillar's journalism in “Catholic Journalists Expose a Scandal, and Liberals Scoff” (August 2, 2021). Mr. Hennessey reported,

“Vox.com described Grindr in 2018 as ‘an underground digital bathhouse’ whose purpose is to ‘help gay men solicit sex, often anonymously, online.’ At the very least most Catholics, liberal or conservative, would say this doesn’t sound like the kind of thing a priest should have on his phone. Is it news? Without a doubt ... If the priest who leads the USCCB is living a life antithetical to Church teaching on matters of human sexuality, It’s a story.”

Is This Really about Human Sexuality?

Complicating this story further, Msgr Jeffrey Burrill is a priest of the Diocese of Lacrosse, Wisconsin whose Ordinary, Bishop William P. Callahan, recently suspended the priestly faculties of another high profile priest, Father James Altman for the stated reason of being “divisive and ineffective.”

The criticism of Jesuit Father James Martin, that The Pillar journalists used “immoral tactics” to “out” Msgr Burrill, is curious at best. It is true that they went after this story with an unexplained laser focus and determination, but their methods were not at all unique in the digital age. Father Martin’s use of the term “out” leaves the impression that he protests exposing Msgr Burrill’s sexual orientation. Father Martin has invested a lot of energy and ink to present and lobby for same-sex unions to be perceived as both normative and acceptable in and outside of the Church.

His rhetoric on this only further harms Msgr Burrill, however. Grindr bills itself as “the largest social network for gay, bisexual, transgender and ‘queer’ people” for the singular purpose of locating and exploiting opportunities for anonymous sexual encounters, often between complete strangers. There is not even the remotest opportunity for relationship, mutuality, love, or companionship in such encounters. This is not a reflection of human sexuality. It is about narcissistic exploitation of oneself and other human beings. It is about sexual compulsion.

If all that has been suggested about Msgr Jeffrey Burrill’s use of the Grindr app is true, he does not need Father Martin’s affirmation or defense, nor does he need our revulsion or contempt. He needs our help. The great tragedy of all this is that the person most in place to help him — his own bishop — is rendered unable or unwilling to do so because of the tabloid frenzy of the media and the bishops’ collective fear of it.

When the story of former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick first surfaced in the arena of public contempt, I wrote a controversial post entitled, “Cardinal Theodore McCarrick and the Homosexual Matrix.” It explained my own vicarious experience of the world and influence of Cardinal McCarrick in the seminary I attended in the 1970s. Its central point cautioned against a witch hunt to root out from the priesthood the existence of same-sex attraction because those who experience it are just as capable of living celibate lives committed to Christ as any other priest or religious. The real impediment to Holy Orders, that post suggests, is not same-sex attraction but rather narcissistic personality disorder, a condition that defies treatment and objectifies others, but is far more detectable in screening a candidate for priesthood or religious life.

I have known many priests who have struggled with same-sex attraction who are exemplary priests. I strongly believe that there is a direct correlation between the health of their lives as men and as priests and their ability to resist narcissism by leading selfless lives. The compulsion for anonymous sexual encounters and the objectification of others exploited by sites like Grindr have a lot more to do with the plague of narcissism than anything resembling human sexuality.

I have also known priests, though in a far smaller number, who gradually descended into the darkness of sexual narcissism and the world of anonymous “hook-ups” that Grindr exploits. Some of these men were sent to a residential treatment center for priests where I served as Director of Admissions. Many were helped, but only to the extent that they could do the hard work of exposing and understanding their narcissistic personalities and commit themselves to selfless and transparent lives and a priesthood centered on Christ.

In nearly every case, their long, slow descent into darkness was known to other priests who did nothing and said nothing to stop or challenge them. In the case of Cardinal McCarrick, it is a fact that many bishops knew of his behavior, but today lie about this. Today he is dismissed, scapegoated and ostracized, but his sins were not just his own. It will merely compound this tragedy, and the Church’s shame, if Msgr Jeffrey Burrill now is left with only one option: to disappear into the night.

Was the Holy See a Victim of Blackmail?

A side story has developed over use of the Grindr app that has led some to draw a possible connection with the Vatican’s troubling agreement with the Chinese Communist Party over the selection of bishops for the state-controlled church. The evidence is enticing, but entirely circumstantial. This aspect of the Grindr app story was first exposed in a Breitbart News article by Thomas Williams, Ph.D. entitled, “‘Extensive’ Gay Hookup App Usage Compromises Vatican Security,” (July 28, 2021). The article draws on the previous article in The Pillar to explore a possible exposure to blackmail for use of the app within Vatican walls.

The Pillar revealed that at least sixteen different mobile devices emitted signals from Grindr within areas of Vatican City not generally open to the public. That’s sixteen cellphones over four days within an eight-month period between March and October 2018. To date, the owners of those phones are unknown. With this information, and a lot of conjecture, some Vatican watchers now suggest that the 2018 Concordat, the contents of which to date remain private, may have been a result of blackmail over use of the app within the Vatican. From my perspective, this is possibly a huge leap of the imagination.

According to the Breitbart article, a Chinese entity was the original owner of the Grindr app. It is surmised that the CCP could have accessed the same data investigated by The Pillar. I have written more than once questioning the secret agreement of 2018 between the Vatican and the Chinese Communist Party. The Holy See appears to have conceded to allowing the CCP to select candidates for bishop in the state-run Chinese Catholic Patriotic Association which was first established by the late Chairman Mao Zedong. I wrote of this just weeks ago in “Pope Francis Suppresses the Prayers of the Faithful.”

Added to the circumstantial evidence is a June 2019 change in the Vatican’s longstanding China policy which previously forbade priests from joining that association. After the ban was lifted, Hong Kong Cardinal Joseph Zen went on record to say that the lifting of that ban was even more destructive than the 2018 agreement itself.

Added to the above evidence has been the relative silence of the Holy See about Chinese atrocities toward the Uyghur people in the XinJiang Autonomous Region, and the increased persecution of priests and other Catholics who remain in the “underground” Church that is loyal to Rome even if Rome is not loyal to them. All of this is indeed cause for grave concern.

However, none of it is evidence of blackmail. Our friend and Canon Law adviser, Father Stuart MacDonald, sees this evidence as being similar in tone and substance to that used by bishops to expel accused priests in cases with no hard evidence. It all seems “credible,” but only in the sense that it “might” be true. It is, however, no measure of justice when it is the only evidence.

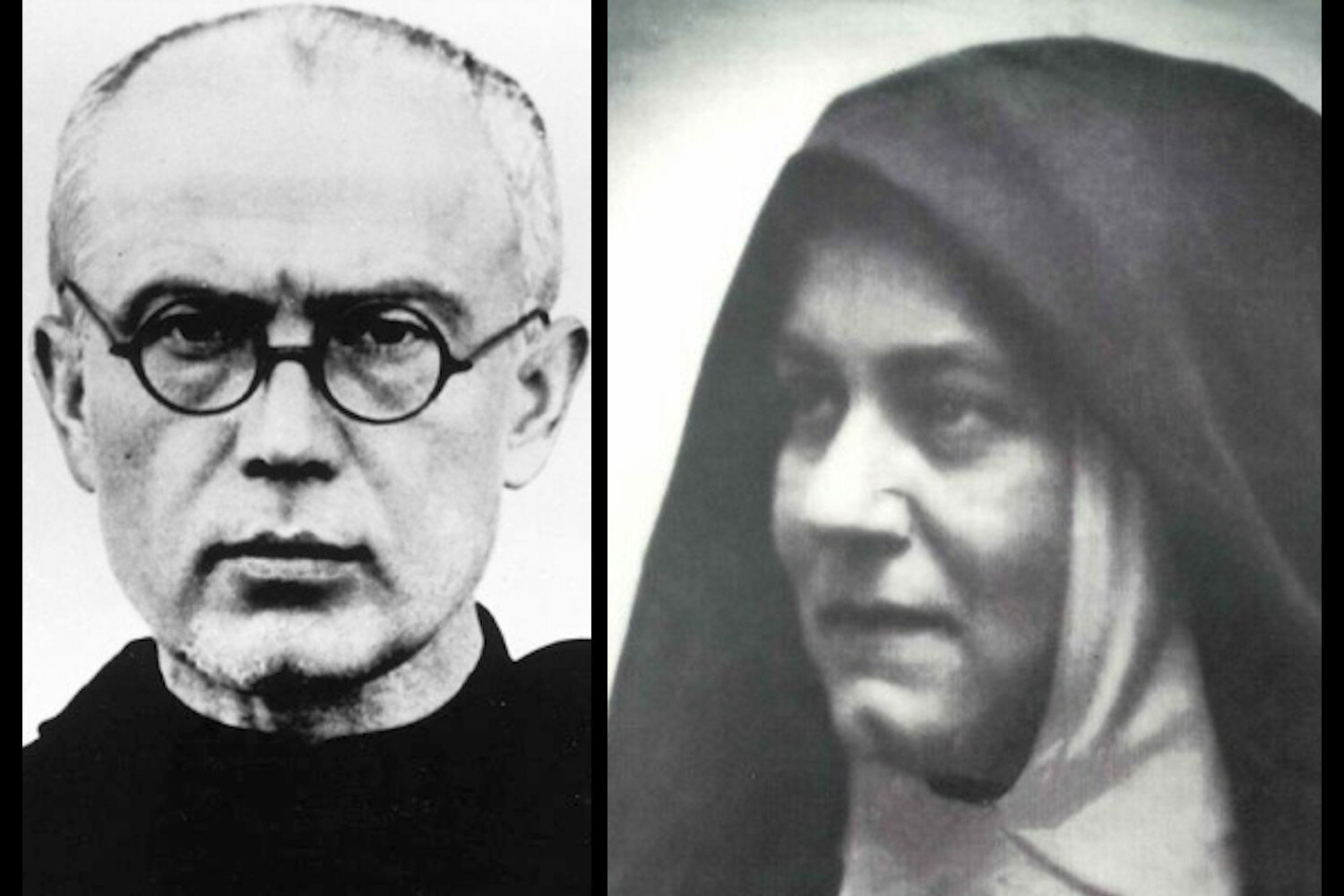

Earlier this month, I posted an important addition to our Library category, “Our Patron Saints.” The post is “Saints and Sacrifices: Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein at Auschwitz.” In 1937, Pope Pius XI published a courageous document entitled, in German, “Mit Brennender Sorge” (With Deep Anxiety). It was a bold confrontation with the Nazi regime over the forced deportation of Jews from Europe. In retaliation, many people were imprisoned. Some were put to death. Among them was Edith Stein, a woman who was born a Jew, became a Catholic, a celebrated university doctor of philosophy, and a Carmelite nun. She was dragged in full Carmelite habit from her convent in Holland, stuffed onto a cattle train, and transported to Auschwitz where she was immediately put to death.

When Pope Pius XII ascended the Chair of Peter shortly thereafter, he was, in a sense, blackmailed by this and other atrocities into silence about Hitler and the Third Reich. Speaking out would have jeopardized many lives, and many underground efforts at diplomacy to save people who were imperiled. To conclude today without evidence that the Pope is silenced by someone holding over his head a story of someone in the Vatican calling a gay hookup app is shameful in comparison. That part of the story might better belong in Soap Opera Digest.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: Please share this important post. Please also visit our Subscribe Page and Special Events. You may also like these relevant posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Cardinal Theodore McCarrick and the Homosexual Matrix

The McCarrick Report & the Silence of the Sacrificial Lambs

Pope Francis Suppresses the Prayers of the Faithful

Saints and Sacrifices: Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein at Auschwitz

Photo courtesy of CNS/L'Osservatore Romano

In Honor of Mom: A Corner of the Veil

Pornchai Moontri and Fr Gordon MacRae have met the challenge of honoring their mothers during a most difficult time in life, the latter through this moving 2009 post.

The photograph above is the house where Father Gordon MacRae grew up just north of Boston. It is the home where his single-parent mother raised three sons and a daughter alone. The stone wall in the front was built by Father Gordon and his brother at ages 15 and 16. It still stands today.

Pornchai Moontri and Fr Gordon MacRae have met the challenge of honoring their mothers during a most difficult time in life, the latter through this moving 2009 post.

Note from Father Gordon: This post, which is dear to my heart, was first published in 2009 three years after my mother’s death. After I decided to repost it, Pornchai Moontri sent me some photos of how he has honored his mother in northern Thailand last month. For the first time in his life, Pornchai took part in the April celebrations of Songkhram, the Thai New Year, and Loy Krathong, the annual Water Festival and its ritual cleansing of the tombs of his mother and grandmother at a Buddhist temple in the village of his birth. (Note: Pornchai wants everyone to know that the shirt was a gift from one of his cousins!)

+ + +

When I was first sent to prison, my mother visited me weekly. She lived North of Boston, about a ninety minute drive from Concord, NH. She was usually brought here by my sister and her husband or by my younger brother. I was very concerned about how my imprisonment affected my mother. The mothers of most priests enjoy a sort of vicarious respect that they cherish with pride. My mother was visiting her priest-son in prison.

My mother was painfully aware that I could have left prison after only one or two years had I been willing to plead guilty to something that never took place. I knew she knew this. One day when we were alone during a visit, I took her hand and asked her if she was disappointed that I did not take a “deal” for the easy way out. She pondered this for a moment, squeezed my hand, and said,

“No, I would have been disappointed if you lived a lie. There’s no freedom in living a lie. I want you to fight for the truth.”

I was very proud of my mother, for in those few simple words she, too, put herself and her pride aside for principle. A few days after our visit, my mother sent me a simple card. It was a quote from Winston Churchill, plain white text on a black background, “Never, ever, ever give up!” It was one of my treasures. The card spent several years on my cell wall, then disappeared one day, lost —as are many such things when I was moved from place to place in the prison.

In the years to follow, my mother became very ill. Her visits were fewer and further between. I witnessed the digression as she appeared in the prison visiting room one day with a cane, then a walker, then a wheelchair — and then I saw her no more. Over the next two years, I could only speak with my mother by telephone. In the last year of her life, my mother and I could not speak at all.

It was a special agony to know that my mother was dying just seventy miles away. As her son and as a priest, I had lost any means to offer support for her except through prayer. I wrote to a priest-friend in Boston, Franciscan Father Raymond Mann, who graciously prepared my mother spiritually for death in my stead. I was most grateful to him, and to my sister and her family who cared for our mother every moment of her last years in this life. On November 5, 2006, my mother died.

Most of you cannot imagine being unable to see or comfort a loved one dying just seventy miles away. There is a barrier between the imprisoned and the free — almost as impenetrable as the barrier between the living and the dead. My duty as her son and as a priest would be carried out in silence in my own heart.

Redemptive Suffering

When I saw the Mel Gibson film, “The Passion of the Christ,” I was struck by the powerful, silent scenes in which Mary viewed her Son’s path to Calvary from a short distance, and yet could not touch him, could not speak to him. I felt as though I was living the reverse of those scenes, that I witnessed from the far side of an abyss the suffering and death of my mother, and could not be present. It was as though I had died before her — already, but not yet.

I was angry. As her son and as a priest, being present to my mother in death was a sacred duty, but one denied to her and to me through the false witness of accusers and the enticement of money — an enticement that has played a far greater role in the Church’s scandal than our bishops and the plaintiff lawyers will admit. How could I not be angry?

“One of the great temptations I have had to face in prison is the impulse to keep a litany of losses. It is a naturally human response to injustice, but the resentment to ensue would be a spiritually toxic weapon of self-destruction.”

My first post on These Stone Walls was “St. Maximilian Kolbe and the Man in the Mirror.” In it, I described something that occurred just six weeks after the death of my mother. I had been standing at the mirror in my cell shaving on the morning of December 23, 2006. I suddenly realized that the equation of my life had just changed, that on that very day I was a priest in prison longer than anywhere else.

The sense of loss and futility was overwhelming until later that same day when I received in the mail an image of Father Maximilian Kolbe in both his Franciscan habit and his prison uniform. I have described in several posts my encounter with St. Maximilian Kolbe just at the point at which the equation changed — the point at which more of my life as a priest was spent in prison than in freedom.

Father Kolbe’s sacrifice of his life for another made me realize the power that exists in sacrifice and especially in the sacrifice of unjust suffering. I have come to know without doubt that suffering offered for another is redemptive of both. It’s a difficult concept for someone on the wrong end of injustice to grasp, and I struggled with it at first. I began to offer my days in prison as a share in the suffering of Christ in the final weeks of my mother’s life. It was all I had to give her.

Newfoundland

My mother, Sophie Kavanagh MacRae, emigrated to the United States from Newfoundland at age 22 in 1949. The oldest of six, she was close to her three sisters and two brothers who remained in Newfoundland. My mother was closest in age and in friendship to her sister, Frances, two years younger.

In 2003, my mother visited her childhood home for the last time.

Even in sickness and in pending death, my mother never lost her Irish sense of humor. During the visit my mother sent me a postcard with a scene from a high cliff overlooking Saint John’s Harbour. She wrote the following message:

“Dear Gordon,

Newfoundland is simply beautiful. I am writing this while visiting Redcliff, a 200-foot sheer cliff where Newfoundlander mothers of old would take their most troublesome sons and threaten to heave them over the edge.

Wish you were here. Love, Mom”

She also sent me a terrific photograph of herself with her sister, Frances at Logy Bay, just north of St. John’s on the Avalon Peninsula where they grew up.

It was the only photo I had of my mother in her last years. I put the photo away, and then lost it. When my mother died, Pornchai helped me search our cell for the photo, but it was gone. It’s difficult for prisoners to hold onto such things. Prisoners’ cells are routinely searched — sometimes even ransacked in the process — and we have very little ability to preserve items we treasure such as photographs. The photo of my mother was lost.

In the July/August, 2009 issue of This Rock magazine (which later became Catholic Answers ), Father Dwight Longenecker has an interesting article, “Weird Things Happen.” He wrote of an experience in the Chapel of the Convent of Saint Gildard in Nevers, France as he prayed before the uncorrupted body of St. Bernadette:

“I kept silence there and noticed a beautiful fragrance of flowers. As I prayed, the fragrance grew stronger, and I felt transported by a presence that was beyond my understanding.”

Father Longenecker — who hosts the Standing on My Head blog — wrote of other phenomena that defy logical explanation in our repository of faith experience. He wrote of Padre Pio’s stigmata, apparitions of the Blessed Mother, healings in the presence of sacred relics. In a later issue of This Rock, Father Longenecker took some heat for what was wrongly interpreted as his dismissal of such experiences.

I found his article to be respectful and serious, with but one small flaw. Father Longenecker later questioned what, exactly, happened to him in that chapel before the body of St. Bernadette, and suggested that we need to be both believing and skeptical.

“Whenever a natural explanation for a seemingly supernatural event is available,” he wrote, “it is to be preferred”

But why should natural explanations preclude the miraculous? Naturally occurring events can be powerful catalysts of actual grace, and as such they seem miraculous. We have all had the experience of coincidence that is so unlikely, so personally shaking that it defies explanation. Who hasn’t picked up the telephone to call a loved one only to find that person already there calling you?

It seems a minor miracle when it happens, something inexplicable and astonishing, then the experience slowly diminishes as doubt and natural skepticism reinterpret the event for us. The task of getting on with life causes us to shrug off the experience over time. Sometimes the balance between belief and skepticism in the modern world can lean too heavily toward the latter.

I wrote of such an event in "A Shower of Roses" in October. While accompanying teenage Michelle through the last weeks of her life, I spoke of St. Therese, the Little Flower, who promised a shower of roses. Michelle, a day away from death, pointed at the ceiling where drifted a helium balloon with a vivid rose imprinted upon it. It left me stunned — for awhile, but in time the trials of life diminished the light of that event. How common are the signs and wonders that come to people of faith? Can we always see them when they arrive?

The Undiscovered Country

In Hamlet Shakespeare called death, “The Undiscovered Country.” I know many people who have suffered the death of someone they love. Think, in the midst of that suffering, of the incredible gift that it contains. Loss is not felt at all but for love, and love is a direct result of grace. It is what folds back a corner of the veil — what links the living to the dead. We have something very special to share with those whose physical life is lost to us: the grace of redemptive suffering, the hope of our prayers, the sacrifice of our trials.

Eight months after my mother’s death, I learned that her beloved sister, Frances, died in Newfoundland. She died on July 10,2007, but I did not learn of it for several days. Prisoners cannot be reached by telephone, so it was July 14th when I received my sister’s letter about the death of my aunt. The next day, July 15th, was my mother’s birthday, the first since her death the previous November. Late that night, I prepared to offer Mass in my cell for the souls of my mother and her sister. Pornchai Moontri was with me for the Mass and told me this week that he remembers this story very well.

Just as Mass began, a prisoner came to my cell to borrow a book. I was irritated. Couldn’t he wait? I had to pull a foot locker from under my bunk and rummage for the book. I found the book and handed it to him, and he left.

I turned back to the Mass, and a moment later there he was again at my door. He walked into my cell and plopped something right onto the corporal I had laid down for Mass. Pornchai and I were both stunned. It was the photo of my mother and Frances that I had lost four years earlier — the photo we searched for in vain when my mother died. It’s the photo above. Just as Mass began on my mother’s birthday — at the very moment I was offering the Mass for her and her sister — their last photograph together found me

An accident? Mere coincidence? It’s a greater leap of faith to dismiss such events as coincidence than to accept them for what they are: personally miraculous gifts of actual grace.

When I looked at the photograph, it was as though someone had lifted a tiny corner of the veil between life and death. I saw something in the photo I hadn’t noticed before. The two sisters stood side by side — my mother on the right — on the shore of a new life, being prepared for the Presence of God. I never saw my mother look happier. I never saw more contentment and hope in her eyes. I never felt so happy for her, so filled with promise that her journey is near its end: Home, her New Found Land.

+ + +

Please share this post in honor of Mother’s Day. You may also wish to visit the posts linked herein:

Padre Pio: Witness for the Defense of Wounded Souls

Padre Pio and Maximilian Kolbe, the Patron Saints behind These Stone Walls, have an obscure thread of connection that magnifies witness, sacrifice, and fatherhood.

Padre Pio and Maximilian Kolbe, the Patron Saints behind These Stone Walls, have an obscure thread of connection that magnifies witness, sacrifice, and fatherhood.

There was an eerie sense about us as Pornchai Maximilian Moontri and I walked around the concrete prison yard at 0500 on September 8, the Feast of the Nativity of Mary. There was not yet any sign of the dawn, nor was there any moon in the sky. If there were stars, we were blinded to them by the blazing prison lights reflected from the high walls that surrounded us. I asked Pornchai to take a long last look at these walls, for he was about to enter the final stretch of his long road to freedom.

Just then, a sliver of bright light emerged above the building where we have lived in a 60-square-foot cell for the last three of our years in prison — 28 for Pornchai and 26 for me. We stood still to watch as the bright half-moon arose above all the walls. I told Pornchai that he will gaze upon the same moon in Thailand that I will see from this very spot. There was a long silence as he considered this, and then it was followed by tears. I had been putting a brave face on things up to this point, but I could no longer contain it.

It is difficult for men to talk and sob at the same time. I do not suggest that women cry more than men. Perhaps men do not cry enough. It is just that there was so much to say, and so I choked back the tears until another time. If you have been reading These Stone Walls for any length of time, then you understand what was transpiring that morning. It was expressed best by Pornchai himself in a recent guest post, “Hope and Prayers for My Friend Left Behind.”

Soon after, we had to end that walk, after fourteen years sharing and building faith, conversion and redemption in a tiny prison cell, Pornchai was taken away and we will never see each other again in this life.

Backing up a little, it was Pornchai who brought up the most urgent and necessary part of our conversation that morning. It goes back to one of the first conversations we ever had about Pornchai’s faith experience. It was back in 2006 just before we were moved into the same cell. He described this in his post above. He walked into my cell, saw an image of St. Maximilian Kolbe on the mirror, and asked, “Is this you?” He described that as one of the most important questions of his life.

Fourteen years later, as we walked in the pre-dawn light of a half moon, he said through tears, “Now I have the answer. You have saved me, but no one is saving you.” We talked a lot about our patron saint, of the mystery of how he came into our lives, and of what his witness means for us. Maximilian went to prison because he was writing the truth. I went to prison on trumped up charges, and have been writing the truth ever since. I told Pornchai that he is a very important and powerful part of that truth. I said that no matter what happens to me now, “you are a living witness to the truth that no past is lived at the expense of the present, that no wounds can prevent a soul in search of God from emerging above prison walls.”

The Wounds of Padre Pio

At this writing, Pornchai is now in a tomb of solitary confinement, with no ability to communicate with the outside world. I can support him only with my prayers, but this should only last a few days. By the time you are reading this, he will have already emerged from that to enter another purgatory: ICE detention awaiting deportation. This is probably the most disorganized, haphazard, inhumane and one-size-fits-all thing that the American government bureaucracy does. But we have a team of advocates working to make this stay as brief as possible. They are in touch with me every day.

The Thai consulate will — hopefully soon — arrange a repatriation flight for Pornchai to return to his native land after a 36-year absence. Under ICE rules, he is allowed to have nothing but the clothes he is wearing. We had the foresight to pack a box of his treasured few possessions — a handmade rosary sent to him by TSW, reader Kathleen Riney, a Saint Maximilian medal, some photographs, and a set of Divine Mercy books by Father Michael Gaitley and others. These include Loved, Lost, Found by Felix Carroll which features a chapter about Pornchai’s life. The box is on its way to Thailand and may arrive ahead of him.

When Pornchai himself arrives in Bangkok, he will have a final 14-day stay in solitary confinement, but it will not be in a cell. The Thai government requires a 14-day quarantine period in a Bangkok hotel. Pornchai will not be allowed to leave his hotel room for the 14 days, but it will be unlike all previous experiences of solitary confinement.

[Editor’s note: You can see the solitary confinement unit that held Pornchai decades ago at wgbh.org/frontline/solitarynation. Pornchai knows many of the solitary confinement prisoners in this documentary about his first prison in Maine. If you haven’t seen this, you can’t begin to know what Pornchai has been through. It’s traumatic just to watch it. It’s the video right at the top of that link.]

One of our friends in Thailand will drop off a Samsung smart phone for Pornchai’s use so he and I can communicate. After 28 years in prison, he has never seen a smart phone. His first assignment is to learn how to answer the phone.

His second assignment will be to learn how to use the phone to read the post that you are reading right now. I want him to see what followed our painful discussion on the morning he left in tears — and left me in tears as well. I want him to ponder the mystery of the other patron saint who insinuated himself behind These Stone Walls with us. I want him to ponder the graces imparted to us by Saint Padre Pio who bore the wounds of Christ for fifty years.

I have been aware of Padre Pio for most of my life. As the young Capuchin studying (aka, misled by) pop psychology in the 1970s, a story I told in “Prison Journal: A Midsummer Night’s Midlife Crisis,” I am ashamed to write that I once denounced Padre Pio’s wounds as psychosomatic. I hope he forgives me for my ignorance back when I knew everything. I knew a lot about Padre Pio back then, but I did not know Padre Pio. Now I do. Pornchai knows him as well. He came to us behind These Stone Walls in a personal and powerful way.

I had already been in prison on false witness for four years back in 1998. I had, for all of those years, been living in a horrible situation with eight men in each prison cell designed for only four. To “honor” Catholics’ reverence for Padre Pio then — six years before he was canonized by Saint John Paul II in 2002 — The New York Times ran an article alleging that Padre Pio was the subject of twelve Vatican investigations in his lifetime. The unjust and inflammatory article alleged that “Padre Pio had sex with female penitents twice a week.”

This was the first inkling I ever had that Padre Pio suffered more than the visible wounds of Christ. He also suffered wounds upon his name, his integrity, his priesthood. Here we were, thirty years to the day since his death, and the “Scandal Sheet of Record” was still repeating an unfounded story for the sole purpose of deflating the faith of Catholics who reverenced him. It resonated with me in a most personal way.

Seven years passed. In April, 2005, a newspaper of integrity, The Wall Street Journal, published a two-part account of false witness, wrongful prosecution and public hysteria entitled, “A Priest’s Story” by Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, Dorothy Rabinowitz. The article was read all over the world. As a result of it, Bill Donohue at the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights asked me to submit an article about my own awareness of false witness. My article was published in the November 2005 issue of Catalyst under the title, “Sex Abuse and Signs of Fraud.”

I was surprised to see that I shared the cover of that issue of Catalyst with a story about how Padre Pio was similarly defamed throughout his life and even after death. None of it was ever substantiated nor was it supported by evidence in any form. On the contrary, many witnesses had testified in Vatican investigations that the detractors were themselves discredited beyond any doubt. That did not stop The New York Times from slander.

The Echoes of a Special Blessing

Among the readers of the WSJ series on my trial’s perversion of justice was Pierre Matthews, a Belgian with dual American citizenship who at the time was living in Chicago. The articles were his first realization — as they were for many — that the whole truth about the nature of Catholic scandal had not been told by the mainstream media. Pierre wrote to me. Months later, on a return trip from Belgium, he diverted his flight itinerary for a stop in Boston from where he drove up to Concord, NH to visit me in prison.

Later in 2005, Pornchai Moontri — who had spent the previous seven years in solitary confinement in Maine — was transferred to the Concord, NH prison where we met. In 2006 we became friends. In 2007 we became roommates. In 2010, on Divine Mercy Sunday, Pornchai renounced his troubled past to become Catholic. Later, in September 2010, I wrote “Saints Alive! Padre Pio and the Stigmata: Sanctity on Trial.”

That post told an amazing story. In an earlier visit with Pierre Matthews, I told him about Pornchai, about how our long and winding roads converged, and about Pornchai’s decision to renounce his past and become Catholic. Pierre told me a remarkable story. He said that when he was growing up in Belgium, his father sent him to a boarding school. In the 1950s, at just about the time I was born, Pierre’s school sponsored a trip to Italy. Pierre’s father wrote to him saying that his trip will take him near a place called San Giovanni Rotondo where there is a very famous priest and mystic who bears the wounds of Christ.

Pierre’s father instructed his skeptical 16-year-old son to take a train to San Giovanni Rotondo and ask to see Padre Pio. Being 16, Pierre did not want to go. But his father was insistent so Pierre read his Father’s account of Padre Pio’s mystical fame that was at the time being suppressed by the Church, but rising up from the sensus fidelium — the sense of the faithful.

When Pierre Matthews learned that Pornchai was to become Catholic, he sent me a registered letter asking — no, insisting — that he be permitted to become Pornchai’s Godfather. Pierre asked me to submit a special request to the prison warden asking approval for Pierre to fly over from Belgium to visit both me and Pornchai. In all the years that I had been here, such a thing was never allowed. No visitor can visit two prisoners at the same time. So I submitted the request with the intent of sending the denial back to Pierre. To my shock, the request came back with a single word: “approved.”

During the special visit, Pierre told us that he indeed took a train to San Giovanni Rotondo at age 16 over a half century earlier. He said he rang the monastery doorbell and asked a friar if he could see Padre Pio. “Impossible” came the curt reply. Pierre explained that his father had sent him from Belgium so the friar invited him inside to be given a prayer card to show his father that he was there. When he stepped inside to be given the card, a strange man in a Capuchin habit, with hands heavily bandaged, was just then walking down the stairs. His eyes were fixed upon Pierre, Padre Pio approached Pierre, placed his bandaged hands upon his head, and blessed him.

Visiting us 55 years later, Pierre said that he knows this blessing was meant for us. He spoke of the long, winding journey from faith that led to his learning about me, then about Pornchai, and then, when These Stone Walls began in 2009, it was what drew Pierre back to faith. It was then, in 2010, that I added Saint Padre Pio as one of the Patron Saints of These Stone Walls. Through Pornchai’s Godfather, Padre Pio shared his wounds with us and became a witness for the defense against our own wounds. It was Pierre who first noted that I was condemned to prison on September 23, 1994, the Feast of Saint Padre Pio.

Among the many letters of Padre Pio to the thousands of pilgrims and penitents who wrote to him, was one dated in the year before his death on September 23, 1968. In that letter, Padre Pio advised a suffering soul to enroll in the Knights at the Foot of the Cross, a spiritual mission founded by Father Maximilian Kolbe for the offering of life’s wounds as a share in the suffering of Christ. I was amazed to read that Padre Pio had such an awareness of our other patron saint two decades before St. Maximilian was canonized. Pornchai and I are both members of the Militia Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross.

Our beloved friend Pierre, Pornchai’s Godfather, passed away in Belgium on July 7 this year. Pornchai and I were blessed to be able to talk with him by telephone in the weeks before his death. He never took redemption for granted, but I know with the certainty of faith that he and Padre Pio have renewed their bond.

So Pornchai, my son, if you are reading this then you must know that there is much more to our life’s wounds than the prison walls that surrounded us and surround me still. To be free of them is not just a matter of the body, but of the heart and soul. So be free. Be free enough to convey to others the great gifts imparted to us by these patron saints. You will no longer have a guest post at These Stone Walls. You will now be a partner in mission, writing from Divine Mercy Thailand about how God is inspiring hearts and souls through the transfiguration of your wounds.

+ + +

Please visit our Special Events page.

+ + +

Saints Maximilian Kolbe and Padre Pio were both canonized by Saint John Paul II.

+ + +

+ + +

Saints and Sacrifices: Maximilian Kolbe and Edith Stein at Auschwitz

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross — Edith Stein — are honored this week as martyrs of charity and sacrifice.

Saint Maximilian Kolbe and Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross — Edith Stein — are honored this week as martyrs of charity and sacrifice.

In a post some years ago I invited our readers to join my friend Pornchai Moontri and me in a personal Consecration to Saint Maximilian Kolbe’s dual movements: the Militia of the Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross. Our Consecration took place at Mass on the night of August 15, the Solemnity of the Assumption, and the day after Saint Maximilian’s Feast Day. Visit the website of the Militia of the Immaculata for instructions for enrolling in the Militia Immaculata and the Knights at the Foot of the Cross.

We’re very moved by the number of people who have pledged to join us in this Consecration. The invitation remains always open.

Consecration as members of Saint Maximilian’s M.I. or Knights at the Foot of the Cross does not mean I plan to take on any more suffering or that I will never again complain. It does not even mean that I accept with open arms whatever crosses I bear and embrace them.

A person who is unjustly imprisoned must do all in his power to reverse that plight just as a person with cancer must do everything possible to be restored to health. Consecration does not mean we will simply acquiesce to suffering and look for more. It means we embrace the suffering of Christ, and offer our own as a share in it. In the end, I know I cannot empty myself, as Christ did, but I can perhaps attain the attitude of “Simon of Cyrene: Compelled to Carry the Cross,” of which my own is but a splinter.

I have written in the past that history has a tendency to treat its events lightly. The centuries have made Saint Patrick, for example, a sort of whimsical figure. History has distorted the fact that he became the saint he is after great personal suffering. Patrick was kidnapped by Irish raiders at the age of 16, forced from his home and family, taken across the Irish Sea and forced into slavery.

The life and death of Saint Maximilian are still too recent to be subjected to the colored glasses through which we often view history and sainthood. As with nearly all the saints — and with some of us who simply struggle to believe — great suffering was imposed on Maximilian Kolbe and he responded in a way that revealed a Christ-centered rather than self-centered life. What happened to Father Maximilian Kolbe must not be removed from what the Germans would call his “sitz im leben,” the “setting in life” of Auschwitz and the Holocaust. As evil as they were, they were the forges in which Maximilian cast off self and took on the person of Christ.

Scene from the 1978 mini-series “Holocaust”

“And the Winner Is . . .”

Do you remember the television “mini-series” productions of the 1970s and 1980s? After the great success of bringing Alex Haley’s “Roots” to the screen, several other forays into history were aired in our living rooms. One of them was a superb and compelling series entitled “Holocaust” that debuted on NBC on April 16, 1978. It was a brilliant and powerful example of television’s potential.

“Holocaust” won several Emmy Awards for NBC in 1978 for outstanding Limited Series, Best Director (Marvin Chomsky), Best Screenplay (Gerald Green), Best Actor (Michael Moriarty), Best Actress (Meryl Streep) and a number of Supporting Actor and other awards. As a historical narrative, however, “Holocaust” was deeply disturbing and shook an otherwise comfortable generation all too inclined to want to forget and move on. That was a complaint during the famous Nuremberg Trials of 1945 and 1946.

Just two years after the Allied Invasion of Germany and Poland ended the war and exposed the Death Camps, writers complained that Americans had lost interest and were not reading about the Nuremberg Trials. The aftermath of war revealed the sheer evil of the Nazi Final Solution, and it was more than most of us could bear to look at — so many did not look.

As I wrote in “Catholic Scandal and the Third Reich,” there are some who would have you believe that the Catholic Church is to be the moral scapegoat of the 20th Century. Viewing “Holocaust” (the miniseries) would quickly shatter any such revisionist history. Its first episode was so graphic in its depiction of Nazi oppression, and caused me so much anguish, that I struggled with whether to watch the rest.

I was 25 years old when it first aired, and finishing senior year at Saint Anselm College, a Benedictine school in New Hampshire. I was a double major in philosophy and psychology, and was in the middle of writing my psychology thesis on the relationship between trauma and depression when “Holocaust” kept me awake all night.

The morning after that first episode, I sought out a friend, an elderly Benedictine monk on campus who recommended the series to me. I thought he might tell me to turn my television off, but I was wrong. “This happened in my lifetime,” he said. “We cannot run from it. So don’t look away. Stare straight into its heart of darkness, and never forget what you see.”

He was right, and his words were eerily similar to those of biographer, George Weigel, who wrote of Pope John Paul II and his interest in Saint Maximilian Kolbe in Witness to Hope (HarperCollins, 1999):

Maximilian Kolbe . . . was the ‘saint of the abyss’ — the man who looked into the modern heart of darkness and remained faithful to Christ by sacrificing his life for another in the Auschwitz starvation bunker while helping his cellmates die with dignity and hope.

— Witness to Hope, p. 447

That was what the Holocaust was: “the modern heart of darkness.” I have been a student of the Holocaust since, but I am no closer to understanding it than I was on that sleepless night in 1978. As I asked in “Catholic Scandal and the Third Reich”:

“How did a society come to stand behind the hateful rhetoric of one man and his political machine? How did masses of people become convinced that any ideology of the state was worth the horror unfolding before their eyes?”

We have all been reading about the breakdown of faith in Europe, and about how decades-old scandals are now being used to justify the abandonment of Catholicism in European culture. This is not a new phenomenon. This madness engulfed Europe just eighty years ago, and before it was over, six million of our spiritual ancestors were deprived of liberty, and then life, for being Jews.

Hitler’s “Final Solution” exterminated fully two-thirds of the Jewish men, women, and children of Europe — and millions of others who either stood in his way or spoke the truth. Among those imprisoned and murdered were close to 12,000 Catholic priests and thousands more women religious and other Catholics. The determination to rid Europe of the Judeo-Christian faith did not begin with claims of sexual abuse, and this is not the first time such claims were used to further that agenda.

The Great Lie and Revealed Truth

This of all weeks keeps me riveted on the Holocaust. It was in this week that two of my dearest spiritual friends were murdered a year apart at Auschwitz by that madman, Hitler, and his monstrous Third Reich. Father Maximilian Kolbe traded his life for that of a fellow prisoner on August 14, 1941, and Edith Stein — who became Carmelite Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross — was dragged from a cattle train and murdered along with her sister, Rosa, immediately upon arrival at Auschwitz on August 9, 1942.

We must not forget this line from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf (Vol. 1, Ch.10, 1925): “The great mass of people … will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one.” In order for a lie to disseminate and prevail, the truth must be controlled. In 1933, the Third Reich imposed the “Editor’s Law” in Germany requiring that editors and publishers join the Third Reich’s Literary Chamber or cease publishing. In 1933 there were over 400 Catholic newspapers and magazines published in Germany. By 1935 there were none.

The Nazi law was imposed in each country invaded by the Reich. In Poland, Father Maximilian was one of many priests sent to prison for his continued writings, but time in prison did not teach him the lesson intended by the Nazis. He was imprisoned again, and he would not emerge alive from his second sentence at Auschwitz. He was not alone in this. Nearly 12,000 priests were sent to their deaths in concentration camps.

“Come, Let Us Go For Our People.”

Edith Stein was the youngest of eleven children in a devout Jewish family in Germany. She was born on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, on October 12, l891. As a young woman, Edith broke her mother’s heart by abandoning her Jewish faith in adolescent rebellion. She was also brilliant, and it was difficult to win an argument with her using reason and logic. She was a master of both.

Edith received her doctorate in philosophy under the noted phenomenologist, Edmund Husserl, and taught at a German university when the Nazis came to power in 1933. During this time of upheaval, Edith converted to Catholicism after stumbling across the autobiography of Saint Teresa of Avila. “This is the truth,” Edith declared after reading it through in one sleepless night. A few years after her conversion, Edith Stein entered a Carmelite convent in Germany taking the name Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Blessed by the Cross).

March 27, 1939 was Passion Sunday, the beginning of Holy Week. In response to a declaration of Adolf Hitler that the Jews would bring about their own extinction, Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross wrote a private note to her Carmelite superior. She offered herself in prayer as expiation against the Anti-Christ who had cast all of Europe into a spiritual stranglehold. In her letter to her superior, Sister Teresa offered herself as expiation for the Church, for the Jews, for her native Germany, and for world peace.

As the Nazi horror overtook Europe, Sister Teresa grew fearful that she was placing her entire convent at risk because of her Jewish roots. Edith was then assigned to a Carmelite Convent in Holland. Her sister, Rosa, who also converted to Catholicism, joined her there as a postulant.

Catholics in France, Belgium, Holland and throughout Europe organized to rescue tens of thousands of Jewish children from deportation to the Death Camps. Philip Friedman, in Roads to Extinction: Essays on the Holocaust (The Jewish Publication Society, 1980) commended the Catholic bishops of the Netherlands for their public protest about the Nazi deportation of Jews from Holland. In retaliation for those bishops’ actions, however, even Jews who had converted to Catholicism were rounded up for deportation to Auschwitz.

A 2010 book by Paul Hamans — Edith Stein and Companions: On the Way to Auschwitz — details the horror of that day. Hundreds of Catholic Jews were arrested in Holland in retaliation for the bishops’ open rebellion, and most were never seen again. This information stands in stark contrast to the often heard revisionist history that Pope Pius XII “collaborated” with the Nazis through his “silence.” He was credited by the chief rabbi of Rome, Eugenio Zolli, with having personally saved over 860,000 Jews and preventing untold numbers of deaths.

The last words heard from Sister Teresa as she was forced aboard a cattle car packed with victims were spoken to her sister, Rosa, “Come, let us go for our people.” On August 9, 1942, Sister Teresa emerged from the cramped human horror of that cattle train into the Auschwitz Death Camp to face The Sorting.

Nobel Prize winner and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel described The Sorting:

“How do you describe the sorting out on arriving at Auschwitz, the separation of children who see a father or mother going away, never to be seen again? How do you express the dumb grief of a little girl and the endless lines of women, children and rabbis being driven across the Polish or Ukranian landscapes to their deaths? No, I can’t do it. And because I’m a writer and teacher, I don’t understand how Europe’s most cultured nation could have done that.”

That August 9th, Edith Stein went no further into the depths of Auschwitz than The Sorting. Some SS officer glared at this brilliant 50-year-old nun in the tattered remains of her Carmelite habit, and declared that she was not fit for work. This woman who had worked every day of her life, who taught philosophy to Germany’s graduate students, who scrubbed convent floors each night, was determined to be “unfit for work” by a Nazi officer who knew it was a death sentence.

Edith and Rosa were taken directly to a cottage along with 113 others, packed in, the doors sealed, and they were gassed to death. Their remains, like those of Maximilian Kolbe a year earlier, went unceremoniously up in smoke to drift through the sky above Auschwitz. And Europe thinks it would be better off now without faith!

“Thus the way from Bethlehem leads inevitably to Golgotha, from the crib to the Cross. (Simeon’s) prophecy announced the Passion, the fight between light and darkness that already showed itself before the crib … The star of Bethlehem shines in the night of sin. The shadow of the Cross falls on the light that shines from the crib. This light is extinguished in the darkness that is Good Friday, but it rises all the more brilliantly in the sun of grace on the morning of the Resurrection.

“The way of the incarnate Son of God leads through the Cross and Passion to the glory of the Resurrection. In His company the way of everyone of us, indeed of all humanity, leads through suffering and death to this same glorious goal.”

— Edith Stein/Sister Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

Maximilian and This Man’s Search for Meaning Part Two

. . . The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us. Within days of reading Man's Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe's sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue. . . .

See Maximilian and This Man's Search for Meaning Part OneAs a young priest in 1982, I was only vaguely familiar with the name Maximilian Kolbe. I remember reading of his canonization by Pope John Paul II, but Father Kolbe's world was far removed from my modern suburban priestly ministry. I was far too busy to step into it.I didn't know that nearly two decades later, Father Kolbe's life, death, and sainthood would be proclaimed on the wall of my prison cell. I also didn't know this would help define the person I choose to be in prison.Being a Jew and not a Catholic, Dr. Viktor Frankl in Man's Search for Meaning, said nothing about Maximilian's sainthood or any miracles attributed to his intercession. Instead, Dr. Frankl was moved by the profound charity of Maximilian, which defied the narcissism of our times.For those unfamiliar with him, the story is simple.The prisoners of Auschwitz were packed into bunkers like cattle. To encourage informants, the camp had a policy that if any prisoner escaped, 10 others would be randomly chosen for summary execution.At the morning role call one day, a prisoner from Maximilian's bunker was missing. Guards chose 10 men to be executed. The 10th fell to the ground and cried for the wife and children he would never see again. Father Kolbe spontaneously stepped forward and said,

"I am a Catholic priest, and I would like to take the place of this man."

Two weeks later, he alone was still alive among the 10 prisoners chained and condemned to starvation. Maximilian was injected with carbolic acid on August 14, 1941, and his remains unceremoniously incinerated.For the unbeliever, all that Maximilian was went up in smoke. Viktor Frankl shared some other corner of that horrific prison. The story of the person Father Kolbe chose to be rippled through the camp. This story offered proof to Viktor Frankl that we can be as much inspired by grace as doomed by despair. We get to choose which will define us.Within days of reading Man's Search for Meaning and learning of Father Kolbe's sacrifice, I received a letter from out of the blue.Conventual Franciscan Father Jim McCurry had been in an airport in Ireland when he heard an Irish priest nearby mention that he corresponds with a priest in a Concord, New Hampshire prison. Father McCurry said he was on his way to visit his order's house in Granby, Massachusetts and would arrange to visit the Concord prison.Weeks later, Father McCurry and I met in the prison visiting room. When I asked him what his "assignment" is, he said,

"Well I just finished a biography of St. Maximilian Kolbe. Have you heard of him?"

Father McCurry went on to say that he was involved in Father Maximilian's cause for sainthood. He had met the man whose great grandfather life was saved by Father Kolbe.A few years later, Father McCurry arranged a Father Maximilian Kolbe exhibit at the National Holocaust Museum. It was then that he sent me the card depicting Father Maximilian clothed in his Franciscan habit with one sleeve in his prison uniform. I keep the card above my mirror in my cell.I can never embrace these stone walls. I can't claim ownership of them. Passively acceding to injustice anywhere contributes to injustice everywhere. Father Maximilian never approved of Auschwitz.One can't understand how I now respond to these stone walls, however, without hearing of Father Maximilian's presence there.

Above my mirror, he refocused my hope in the light of Christ. The darkness can never overcome it.

What hope and freedom there is in that fact! The darkness can never, ever, ever overcome it!Please share with me your comments below in the comments area.