“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr. Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

— Deacon David Jones

Cardinal Bernard Law on the Frontier of Civil Rights

Former Boston Archbishop, Cardinal Bernard Law was vilified by The Boston Globe and SNAP, but before that he was a champion of justice in the Civil Rights Movement.

Former Boston Archbishop, Cardinal Bernard Law was vilified by The Boston Globe and SNAP, but before that he was a champion of justice in the Civil Rights Movement.

June 19, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

Note from Fr MacRae: I first wrote this post in November 2015. I wrote it in the midst of a viral character assassination of a man who had become a convenient scapegoat for what was then the latest New England witch hunt. That man was Cardinal Bernard Law, Archbishop of Boston. I have to really tug hard to free this good man’s good name from the media-fueled availability bias that so mercilessly tarnished it back then. A good deal more has come to light, and I get to have the last word.

By coincidence, and it was not planned this way, but the date of this revised reposting is June 19, 2024, the day that the United States commemorates the emancipation of African American slaves on June 19, 1865 in Galveston, Texas. As you will read herein, Cardinal Bernard Law was a national champion in the cause for Civil Rights and racial equality.

+ + +

Four years after The Boston Globe set out to sensationalize the sins of some few members of the Church and priesthood, another news story — one subtly submerged beneath the fold — drifted quietly through a few New England newspapers. After a very short life, the story faded from view. In 2006, Matt McGonagle resigned from his post as assistant principal of Rundlett Middle School in Concord, New Hampshire. Charged with multiple counts of sexually assaulting a 14-year-old high school student six years before, McGonagle ended his criminal case by striking a plea deal with prosecutors. McGonagle pleaded guilty to the charges on July 28, 2006.

He was sentenced to a term of sixteen months in a local county jail. An additional sentence of two-and-a-half to five years in the New Hampshire State Prison was suspended by the presiding judge in Merrimack County Superior Court — the same court that declined to hear evidence or testimony in my habeas corpus appeal in 2013 after having served 20 years in prison for crimes that never took place.

In a statement, Matt McGonagle described the ordeal of being prosecuted. He said it was “extraordinarily difficult,” and thanked his “many advocates” who spoke on his behalf. In the local press, defense attorney James Rosenberg defended the plea deal for a sixteen month county jail sentence:

“The sentence is fair, and accurately reflects contributions that Matt has made to his community as an educator.”

— Melanie Asmar, “Ex-educator pleads guilty in sex assault,” Concord Monitor, July 29, 2006

Four years earlier, attorney James Rosenberg was a prosecutor in the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office from where he worked to prosecute the Diocese of Manchester for its handling of similar, but far older claims against Catholic priests.

The accommodation called for in the case of teacher/principal Matt McGonagle — an insistence that he is not to be forever defined by the current charges against him — was never even a passing thought in the prosecutions of Catholic priests. Those cases sprang from the pages of The Boston Globe, swept New England, and then went viral across America. The story marked The Boston Globe’s descent into “trophy justice.”

Cardinal Sins

I have always been aware of this inconsistency in the news media and among prosecutors and some judges, but never considered writing specifically about how it applied to Cardinal Bernard Law until I read Sins of the Press, a book by David F. Pierre, Jr. On page after page it cast a floodlight on The Boston Globe’s Pulitzer-endorsed lynching of Cardinal Law, offered up as a scapegoat for The Scandal and driven from Boston by the news media despite having never been accused, tried, or convicted of any real crime.

Does the “lynching of Cardinal Law” seem too strong a term? Historically, the word “lynching” came into the English lexicon from the name of Captain William Lynch of Virginia who acted as prosecutor, judge and executioner. He became notorious for his judgment-sans-trial while leading a band to hunt down Loyalists, Colonists suspected of loyalty to the British Crown in the War for Independence in 1776.

The term applies well to what started in Boston, then swept the country. Most of those suspected or accused in the pages of The Boston Globe, including Cardinal Bernard Law, were never given any trial of facts. As I recently wrote in, “To Fleece the Flock: Meet the Trauma-Informed Consultants,” many of the priests were deceased when accused, and many others faced accusations decades after any supportive evidence could be found, or even looked for. The Massachusetts Attorney General issued an astonishing statement given short shrift in the pages of The Boston Globe:

“The evidence gathered during the course of the Attorney General’s sixteen-month investigation does not provide a basis for bringing criminal charges against the Archdiocese and its senior managers.”

— Commonwealth of Massachusetts Attorney General Thomas Reilly, “Executive Summary and Scope of the Investigation,” July 23, 2003

So I decided to explore the story of Cardinal Bernard Law for Beyond These Stone Walls. When I first endeavored to write about him, he had been virtually chased from the United States by some in the news media and so-called victim advocates deep into lawsuits to fleece the Church. Though not intended originally, my post was to be published on November 4, 2015, which also happened to be Cardinal Law’s 84th birthday.

When I wrote of my intention to revisit the story of Cardinal Bernard Law from a less condemning perspective, it sparked very mixed feelings among some readers. A few wrote to me that they looked forward to reading my take on the once good name of this good priest. A few taunted me that this was yet another “David v Goliath” task. Others wrote more ominously, “Don’t do it, Father! Don’t step on that minefield! What if they target you next?” That reaction is a monument to the power of the news media to spin a phenomenon called “availability bias.”

A while back, I was invited by Catholic League President Bill Donohue to contribute some articles for Catalyst, the Journal of the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights. My second of two articles appeared in the July/August 2009 issue just as Beyond These Stone Walls began. It was entitled “Due Process for Accused Priests” and it opened with an important paragraph about the hidden power of the press to shape what we think:

“Psychologist Daniel Kahneman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2002 for his work on a phenomenon in psychology and marketing called ‘availability bias.’ Kahneman demonstrated the human tendency to give a proposition validity just by how easily it comes to mind. An uncorroborated statement can be widely seen as true merely because the media has repeated it. Also in 2002, the Catholic clergy sex abuse scandal swept out of Boston to dominate news headlines across the country….”

This is exactly what happened to Cardinal Law. There was a narrative about him, an impression of his nature and character that unfolded over the course of his life. I spent several months studying that narrative and it is most impressive.

Then that narrative was replaced by something else. With a target on his back, the story of Cardinal Law was entirely and unjustly rewritten by The Boston Globe. Then the rewrite was repeated again and again until it took hold, went viral, and replaced in public view the account of who this man really was.

Even some in the Church settled upon this sacrificial offering of a reputation. Perhaps only someone who has known firsthand such media-fueled bias can instinctively recognize it happening. Suffice it to say that I instinctively recognized it. I offer no other defense of my decision to visit anew the first narrative in the story of who Bernard Law was. If you can set aside for a time the availability bias created around the name of Cardinal Bernard Law, then you may find this account to be fascinating, just as I did.

From Harvard to Mississippi

As this account of a courageous life and heroic priesthood unfolded before me, I was eerily reminded of another story, one I came across many years ago. It was the year I began to seek something more than the Easter and Christmas Catholicism I inherited. It was 1968, and I was fifteen years old in my junior year at Lynn English High School just north of Boston. Two champions of the Civil Rights Movement I had come to admire and respect in my youth — Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy — had just been assassinated. And just as my mind and spirit were being shaped by that awful time, I stumbled upon something that would refine for me that era: the great 1963 film, The Cardinal.

Based on a book of the same name by Henry Morton Robinson (Simon & Schuster 1950), actor Tom Tryon portrayed the title role of Boston priest, Father Stephen Fermoyle who rose to become a member of the College of Cardinals after a heroic life as an exemplary priest. It was the first time I encountered the notion that priesthood might require courage, and I wondered whether I had any. I was fifteen, sitting alone at Mass for the first time in my life when this movie sparked a scary thought.

Father Fermoyle was asked by the Apostolic Nuncio to tour the southern United States “between the Great Smokies and the Mississippi River” — an area known for anti-Catholic prejudice. He was tasked with writing a report on the state of the Catholic Church there during a time of great racial unrest.

In the script (and in the book which I read later) Mississippi Chancery official, Monsignor Whittle (played in the film by actor, Chill Wills) was fearful of the racist, anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan. He tried to dissuade Father Fermoyle from making any waves, but his mere presence there would set off a tidal wave of suspicion. In a horrific scene, Father Fermoyle was kidnapped in the night, blindfolded, and driven to the middle of a remote field — a field where many young black men had disappeared.

His blindfold removed, he found himself surrounded by men in sheets and white hoods, illuminated by the light of a burning cross. Father Fermoyle was given a crucifix and ordered to spit on it or face the scourging of Christ. Henry Morton Robinson’s book conveys the scene:

“He held the crucifix between thumb and forefinger, lofting it like a lantern in darkness…. Ancient strength of martyrs flowed into Stephen’s limbs. Eyes on the gilt cross, he neither flinched nor spoke. [The music played] ‘In Dixieland I’ll take my stand.’ Stephen prayed silently that no drop of spittle, no whimpering plea for mercy, would fall from his lips before the end… The sheeted men climbed into their cars. Not until the last taillight had disappeared had Stephen lowered the crucifix.”

— The Cardinal, pp 412-413

This could easily have been a scene from the life of Father Bernard Law. Born on 4 November 1931 in Torreon, Mexico, Bernard Francis Law spent his bilingual childhood between the United States, Latin America, and the Virgin Islands. His father was a U.S. Army Captain in World War II and Bernard was an only child. Very early in life, he learned that acceptance does not depend on race, or color, or creed, and once admonished his classmates in the Virgin Islands that “Never must we let bigotry creep into our beings.”

At age 15, Bernard read Mystici Corporis, a 1943 Encyclical of Pope Pius XII that Bernard later described as “the dominant teaching of my life.” He was especially touched by the language of inclusion of a heroic Pope in a time of great oppression. The encyclical was banned in German-occupied Belgium for “subversive” lines connecting the Mystical Body of Christ with the unity of all Christians, transcending barriers such as race or politics.

As a weird aside, I was in shock and awe as I sat typing this post when I asked out loud, “How could I find a copy of Mystici Corporis while stuck in a New Hampshire prison cell?” Then our convert friend, Pornchai Moontri jumped from his bunk, pulled out his footlocker containing the sum total of his life, and handed me a heavily highlighted copy of the 1943 Encyclical. I haven’t yet wrapped my brain around that, but it’s another post for another time.

While attending Harvard University, Bernard Law found a vocation to the priesthood during his visits to Saint Paul’s Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. After graduating from Harvard in 1953, the year I was born, a local bishop advised him that Boston had lots of priests and he should give his talents to a part of the Church in need. At age 29, Father Bernard Law was ordained for what was the Diocese of Natchez-Jackson, Mississippi.

Standing before the Mask of Tyranny

The year was 1961. The Second Vatican Council would soon open in Rome, and the Civil Rights Movement was gathering steam (and I do mean steam!) in the United States, Father Law immersed himself in both. A Vicksburg lawyer once remarked that Father Law “went into homes as priests [there] had never done before.” With a growing reputation for erudition and bridge building on issues many others simply avoided, Bernard was summoned by his bishop to the State Capital to become editor of the diocesan weekly newspaper, then called The Mississippi Register.

It was there that the courage to proclaim the Gospel took shape in him, and became, along with his brilliant mind, his most visible gift of the Holy Spirit. Another young priest of that diocese noted that Father Law’s racial attitudes — shaped by his childhood in the Virgin Islands — were different from those of most white Mississipians. “He felt passionately about racial justice from the first moment I knew him,” the priest wrote. “It wasn’t a mere following of teaching, it came from his heart.”

I know many Mississippi Catholics today — including many who read Beyond These Stone Walls — but in the tumultuous 1960s, Catholics were a small minority in Mississippi. They were also a target for persecution by the Ku Klux Klan which was growing in both power and terror as the nation struggled with a burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.

An 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision in “Plessy v. Ferguson” had defined the doctrine of “separate but equal” as a Constitutional nod to racial segregation, but in 1954 in “Brown v. Board of Education,” the Supreme Court based a landmark desegregation ruling on solid evidence that “separate” was seldom “equal.” Opposition to the ruling grew throughout the South, and so did terrorist Klan activities. In 1955, the murder of a black Mississippi boy, 14-year-old Emmett Till, rocked the state and the nation, as did the acquittal of his accused white killers.

This was the world of Father Bernard Law’s priesthood. Up to that time, the diocesan newspaper, The Mississippi Register, had been visibly timid on racial issues, but this changed with this priest at the helm. In June of 1963 he wrote a lead story on the evils of racial segregation citing the U.S. Bishops’ 1958 “Statement on Racial Discrimination and the Christian Conscience.”

One week later, the respected NAACP leader Medgar Evers was gunned down outside his Jackson, Mississippi home. Both Father Law and (then) Natchez-Jackson Bishop Richard Gerow boldly attended the wake for Medgar Evers under the watchful eyes of the Klan. Father Law’s next issue of The Mississippi Register bore the headline, “Everyone is Guilty,” citing a statement by his Bishop that many believe was written by Bernard Law:

“We need frankly to admit that the guilt for the murder of Mr. Evers and the other instances of violence in our community tragically must be shared by all of us… Rights which have been given to all men by the Creator cannot be the subject of conferral or refusal by men.”

Father Law and Bishop Gerow were thus invited to the White House along with other religious leaders to discuss the growing crisis in Mississippi with President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Later that summer, Father Law challenged local politicians in The Mississipi Register for their lack of moral leadership on racial desegregation, stating “Freedom in Mississippi is now at an alarmingly low ebb.” Massachusetts District Judge Gordon Martin, who was a Justice Department attorney in Mississippi at that time, once wrote for The Boston Globe that Father Law…

“…did not pull his punches, and the Register’s editorials and columns were in sharp contrast with the racist diatribes of virtually all of the state’s daily and weekly press.”

Later that year, Father Law won the Catholic Press Association Award for his editorials. In “Freedom Summer” 1964, when three civil rights workers were missing and suspected to have been murdered, Father Bernard Law openly accepted an invitation to join other religious leaders to advise President Lyndon Johnson on the racial issues in Mississippi. When the bodies of the three slain young men were found buried at a remote farm, the priest boldly issued a challenge to stand up to the crisis:

“In Mississippi, the next move is up to the white moderate. If he is in the house, let him now come forward.”

Later that year Father Law founded and became Chairman of the Mississippi Council on Human Relations. Then the home of a member, a rabbi, was bombed. Then another member, a Unitarian minister, was shot and severely wounded. The FBI asked Father Law to keep them apprised of his whereabouts, and Bishop Gerow, fearing for his priest’s safety, ordered him from the outskirts of Jackson to the Cathedral rectory, but Bernard Law feared not.

Cardinal Law’s life and mine crossed paths a few times over the course of my life as a priest. I mentioned above that while attending Harvard University, Bernard Law found his vocation to the priesthood during visits to Saint Paul’s Church in Cambridge. Many years later, in 1985, my uncle, Father George W. MacRae, SJ, the first Roman Catholic Dean of Harvard Divinity School and a renowned scholar of Sacred Scripture, passed away suddenly at the age of 57. I was a concelebrant at his Mass of Christian Burial at Saint Paul’s Church in Cambridge. Concelebrating with me was Cardinal Bernard Law where his life as a priest first took shape.

In 2013, The New York Times sold The Boston Globe for pennies on the dollar.

On December 20, 2017, Cardinal Bernard Law passed from this life in Rome.

Oh, that such priestly courage as his were contagious, for many in our Church could use some now. Thank you, Your Eminence, for the gift of a courageous priesthood. Let us not go gentle into The Boston Globe’s good night.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: I am indebted for this post to the book, Boston’s Cardinal : Bernard Law, the Man and His Witness, edited by Romanus Cessario, O.P. with a Foreword by Mary Ann Glendon (Lexington Books, 2002).

You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

Saint John Paul the Great: A Light in a World in Crisis

Pell Contra Mundum: Cardinal Truths about the Synod

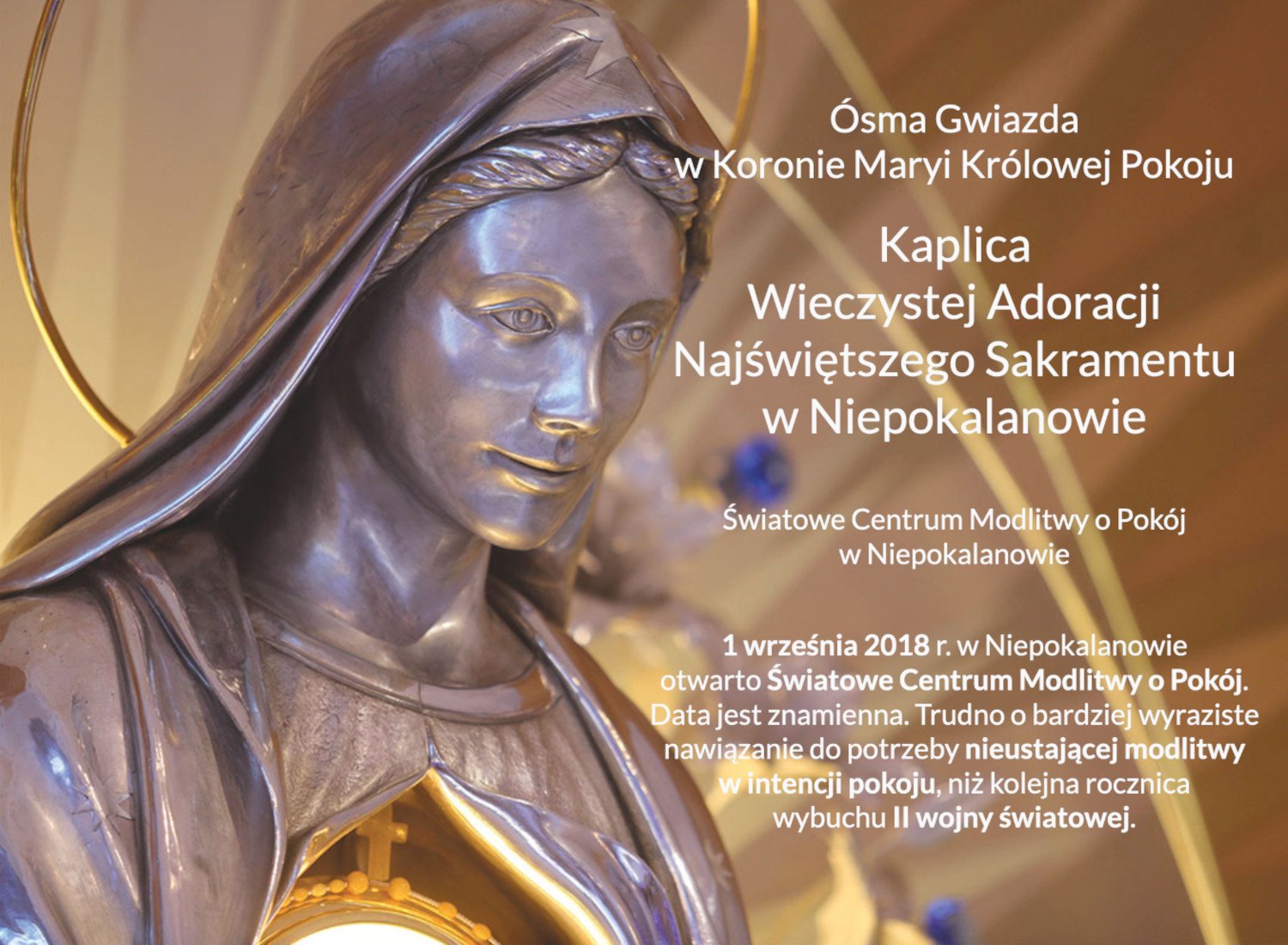

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The Twilight of Fatherhood: Cry, the Beloved Country

Fatherhood fades from the landscape of the human heart to the peril of the souls of our youth. For some young men in prison, absent fathers conjure empty dreams.

Fatherhood fades from the landscape of the human heart to the peril of the souls of our youth. For some young men in prison, absent fathers conjure empty dreams.

June 12, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

“Cry, the beloved country, for the unborn child that is the inheritor of our fear. Let him not love the earth too deeply. Let him not laugh too gladly when the water runs through his fingers, nor stand too silent when the setting sun makes red the veld with fire. Let him not be too moved when the birds of his land are singing, nor give too much of his heart to a mountain or a valley. For fear will rob him of all if he gives too much.”

— Alan Paton, Cry, the Beloved Country, 1948

I was five days shy of turning fifteen years old and looking forward to wrapping up the tenth grade at Lynn English High School just north of Boston on April 4, 1968. That was the day Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered in Memphis, Tennessee. On that awful day, the Civil Rights struggle in America took to the streets. History eventually defined its heroes and its villains.

There is an unexpected freedom in being who and where I am. I can write the truth without the usual automatic constraints about what it might cost me. There is only one thing left to take from me, and these days the clamor to take it seems to have abated. That one thing is priesthood which — in this setting, at least — places me in the supporting cast of a heart-wrenching drama.

But first, back to 1968. Martin Luther King’s “I Had a Dream” speech still resonated in my 14-year-old soul when his death added momentum to America’s moral compass spinning out of control. I had no idea how ironic that one line from Martin’s famous speech would be for me in years to come: “From the prodigious hills of New Hampshire, Let Freedom Ring!”

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, fourteen years to the day before I would be ordained a priest, former Attorney General and Civil Rights champion, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, was murdered in Los Angeles after winning the California primary. The Democratic National Convention in Chicago that August was marked by calamitous riots as Vice President Hubert Humphrey became the nominee only to lose the 1968 election to Richard Nixon in November.

Cry, the Beloved Country

It was at that moment in history — between the murders of two civil rights giants, one black and one white — that a tenth grade English teacher in a racially troubled inner city high school imposed his final assignment to end the school year. It was a book and a book report on Alan Paton’s masterpiece novel set in South Africa during Apartheid. It was Cry, the Beloved Country.

In a snail mail letter some months ago, a reader asked me to write about the origins of my vocation. His request had an odd twist. He wanted me to write of my call to priesthood in light of where it has put me, “so that we might have hope when God calls ordinary people to extraordinarily painful things.” I recently tried to oblige that request when I wrote “The Power and the Glory If the Heart of a Priest Grows Cold.”

I gave no thought to priesthood in the turmoil of a 1968 adolescence. Up to that time I gave little thought to the Catholic faith into which I was born. At age 15, like many adolescents today if left to their own devices, my mind was somewhere else. We were Christmas and Easter Catholics. I think the only thing that kept my family from atheism was the fact that there just weren’t enough holidays.

My first independent practice of any faith came at age 15 just after reading Cry, the Beloved Country. It started as an act of adolescent rebellion. My estranged father was deeply offended that I went to Mass on a day that wasn’t Christmas or Easter, and my decision to continue going was fueled in part by his umbrage.

But there was also something about this book that compelled me to explore what it means to have faith. Written by Alan Paton in 1948, Cry, the Beloved Country was set in South Africa against the backdrop of Apartheid. I read it in 1968 as the American Civil Rights movement was testing the glue that binds a nation. That was 56 years ago, yet I still remember every facet of it, for it awakened in me not just a sense of the folly of racial injustice, but also the powerful role of fatherhood in our lives. It is the deeply moving story of Zulu pastor, Stephen Kumalo, a black Anglican priest driven to leave the calm of his rural parish on a quest in search of his missing young adult son, Absalom, in the city of Johannesburg.

South Africa during Apartheid is itself a character in the book. The city, Johannesburg, represents the lure of the streets as a looming cultural detriment to fatherhood, family, faith and tradition. Fifty-six years after reading it, some of its lines are still committed to memory:

“All roads lead to Johannesburg. If you are white or if you are black, they lead to Johannesburg. If the crops fail, there is work in Johannesburg. If there are taxes to be paid, there is work in Johannesburg. If the farm is too small to be divided further, some must go to Johannesburg. If there is a child to be born that must be delivered in secret, it can be delivered in Johannesburg.”

— Cry, the Beloved Country, p. 83

Apartheid was a system of racial segregation marked by the political and social dominance of the white European minority in South Africa. Though it was widely practiced and accepted, Apartheid was formally institutionalized in 1948 when it became a slogan of the Afrikaner National Party in the same year that Alan Paton wrote his influential novel.

Nelson Mandela, the famous African National Congress activist, was 30 when the book was published. I wonder how much it inspired his stand against Apartheid that condemned him to life in prison at age 46 in 1964 South Africa. His prison became a symbol that brought global attention to the struggle against Apartheid which finally collapsed in 1991. After 26 years in prison, Nelson Mandela shared the Nobel Peace Prize with South African President F.W. de Klerk in 1993. A year later, Nelson Mandela was elected president in South Africa’s first fully democratic elections.

In the Absence of Fathers

I never knew my teacher’s purpose for assigning Cry, the Beloved Country at that particular moment in living history, but I have always assumed that it was to instill in us an appreciation for the struggle for civil rights and racial justice. I never really needed much convincing on the right path on those fronts, but the book had another, more powerful impact that seemed unintended.

That impact was the necessity of strong and present fathers who are up to the sacrifices required of them, and especially so in the times that try men’s souls. There is a reason why I bring this book up now, 56 years after reading it. I had a friend here in this prison who had been quietly standing in the background. I will not name him because there are people on two continents who know of him. He is African-American in the truest sense, a naturalized American citizen brought to this country when his Christian family fled Islamic oppression in their African nation. He was 20 years old when we met, and had been estranged from his father who was the ordained pastor of a small Evangelical congregation in a city not so far from our prison.

I came to know this young prisoner when he was moved to the place where I live. He disliked the new neighborhood immensely at first, finding little in the way of common ground, but Pornchai Moontri and his friends managed to draw him in. Perhaps what finally won him over was the fact that we, too, were in a strange land here. Pornchai brought him to me and introduced me as “everyone’s father here.”

We recruited him on Porchai’s championship baseball team which won the 2016 pennant defeating eight other teams.

I broke the ice one day when I showed our new friend a copy of a weekly traffic report for this blog. He was surprised to see a significant number of visits from the land of his birth. Our friend’s African name was hardly pronounceable, but many younger prisoners have “street names.” So after some trust grew a little between us, he told me some of the story of his life. It was then that I began to call him “Absalom.” The photo at the top of this post is Pornchai’s 2016 championship baseball team in which Pornchai, our old friend Chen (now in China), Absalom, and I are all pictured.

I do not think that I was even conscious at the time of the place in my psyche from which that name was dusted off. He did not object to being called “Absalom,” but it puzzled him.

It puzzled me, too. Absalom was the third son of King David in the Hebrew Scriptures, our Old Testament. In the Second Book of Samuel (15:1-12) Absalom rebelled against his father, staging a revolt that eventually led to his own demise. In the forest of Ephraim, Absalom was slain by Joab, David’s nephew and the commander of his armies. David bitterly mourned the loss of his son, Absalom (2 Samuel 19:1-4).

When I told this story to our new friend,he said, “that sounds like the right name for me.” I told him that in Hebrew, Absalom means “my father is peace.” But even as I said it, I remembered that Absalom is also the name of Pastor Stephen Kumalo’s missing son in Cry, the Beloved Country.

So I told my friend the story of how Absalom’s priest-father in South Africa had instilled in him a set of values and respect for his heritage, of how poverty and oppression caused him to leave home in search of another life only to be lured ever more deeply into the city streets of Johannesburg. I told of how his father sacrificed all to go in search of him.

I also told my friend that I read this book at age 15 in my own adolescent rebellion, and the story was so powerful that it has stayed with me for all these years and shaped some of the most important parts of my life. I told Absalom of the Zulu people and the struggles of Apartheid, a word he knew he once heard, but had no idea of what it meant. I told him that the Absalom of the story left behind his proud and spiritually rich African culture just to succumb to the lure of the street and of how he forgot all that came before him.

“That’s my story!” said Absalom when I told him all this. So the next day I went in search of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country. The prison library had a dusty old copy so I brought it back for Absalom to read, and he struggled with it. A part of the struggle is the Zulu names and terms that are vaguely familiar deep in our Absalom’s cultural memory. Another part of the struggle is the story itself, not just of Apartheid, but of the painful estrangement that grew between father and son, an estrangement that our Absalom could not articulate until now.

So then something that I always believed was going to happen, did happen. Absalom told me that he has contacted his mother to ask his father to visit him for the first time in the years that he has been in prison. He said they plan to visit on Father’s Day. They have a lot to talk about, and that is a drama for which I feel blessed to be in the supporting cast — all the rest of prison BS notwithstanding!

But there is something else. There is always something else. When I began writing this post, I asked Absalom to lend me his copy of Cry, the Beloved Country. When he brought it to me, he pointed out that he has only twenty pages left and wanted to finish it that night. “This is the first book I have ever read by choice,” he said, “and I don’t think I could ever forget it.” Neither could I.

As I thumbed through the book looking for a passage I remember reading 56 years ago (the one that begins this post), I came to a small bookmark near the end that Absalom used to mark his page. It was “A Prisoner’s Prayer to Saint Maximilian Kolbe.” I asked my friend where he got it, and he said, “It was in the book. I thought you put it there!” I did not. God only knows how many years that prayer sat inside that book waiting to be discovered, but here it is:

O Prisoner-Saint of Auschwitz, help me in my plight. Introduce me to Mary, the Immaculata, Mother of God. She prayed for Jesus in a Jerusalem jail. She prayed for you in a Nazi prison camp. Ask her to comfort me in my confinement. May she teach me always to be good.

If I am lonely, may she say, ‘Our Father is here.’

If I feel hate, may she say, ‘Our Father is love.’

If I sin, may she say, ‘Our Father is mercy.’

If I am in darkness, may she say, ‘Our Father is light.’

If I am unjustly accused, may she say, ‘Our Father is truth.’

If I lose hope, may she say, ‘Our Father is with you.’

If I am lost and afraid, may she say, ‘Our Father is peace.’

And that last line, you may recall, is the meaning of Absalom.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: South Africa is also home to Kruger National Park which forms its eastern border with Mozambique. Kruger National Park was also the setting for the most well read of our Fathers Day posts, the first those linked below:

In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men

Coming Home to the Catholic Faith I Left Behind

If Night Befalls Your Father, You Don’t Discard Him! You Just Don’t!

Saint Joseph: Guardian of the Redeemer and Fatherhood Redeemed

+ + +

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

The Power and the Glory If the Heart of a Priest Grows Cold

After 42 years of priesthood, 30 unjustly in prison, ‘The Whisky Priest,’ the central figure of Graham Greene’s best known novel, comes to my mind in darker times.

After 42 years of priesthood, 30 unjustly in prison, ‘The Whisky Priest,’ the central figure of Graham Greene’s best known novel, comes to my mind in darker times.

June 5, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

“You are sure to find another cross if you flee the one you bear.”

— Anonymous Mexican Proverb

+ + +

I was ordained to the priesthood on June 5, 1982, the sole candidate for priesthood in the entire State of New Hampshire that year. On the next day, June 6, 1982, I was nervously standing in a corner in the Sacristy as I prepared to offer my First Mass in Saint John the Evangelist Church in Hudson, New Hampshire. The church was packed with friends, family, and strangers from near and far. I was standing in a corner because the Sacristy was filled with my brother priests all vesting to join me for the occasion. I imagined they were watching me for signs that I might flee.

I peered through the open sacristy door at the huge, anticipating crowd and my anxiety level was off the scales. I wished for a way to calm my nerves. Just then, a young lady came into the sacristy and handed me a written note. The driver of a Buick out in the parish parking lot had left the lights on and a thoughtful person jotted down the license plate number. So I totally broke protocol. I walked out of the sacristy into the sanctuary, approached the lectern microphone, and announced that someone had parked a car with its lights still on.

It worked! All the attention was suddenly off me as everyone looked around to see who would get up and embarrassedly walk outside. Then, still at the microphone, I announced, “I don’t know what the rest of you are expecting because I don’t have a clue how to say Mass!” The church erupted in laughter and spontaneous applause, and my anxiety went up in smoke. Back in the sacristy, the others did not understand what I had said. “What are you up to?” They asked.

In the years to follow, as you know, priesthood took me down some dark side roads. In many ways, and at many times over those years, I have felt as though I had been an utter failure as a priest. I should not be in this prison-place from where I write yet another epitaph on yet another year of priesthood offered up like incense to drift out beyond these stone walls. Yet here I am, and in the midst of sorrow and tears, I am powerless to change any of it.

I know today that I had been caught up in a dense web of corruption that resists unraveling despite some concerted efforts. I did not see any of this corruption as it arose around me. Priests tend not to be attuned to such things, but others have written about it. Among them is Claire Best, a most tenacious investigator, researcher, independent writer, and Hollywood talent agent who wrote, “New Hampshire Corruption Drove the Fr. Gordon MacRae Case.”

On the Day of Padre Pio

Back in 2009 as my 27th anniversary of priesthood loomed, this blog was just beginning to take shape. I did not foresee that coming either. I did not even know what a blog was. It was proposed to me by a writer in Australia. This is a familiar story to most readers, but I recently came upon a different perspective on this blog’s beginning. It’s a sort of parallax view, a telling of the same story but from a different angle. From his newfound cradle of freedom in Thailand, Pornchai-Max Moontri wrote about this with some help from our editor. We will link to it again at the end of this post, but if you plan to read it, bring a tissue. It is, “On the Day of Padre Pio, My Best Friend Was Stigmatized.”

On the very day I was ordained in 1982, my friend, Pornchai Moontri was eight years old, living in abject poverty, but happy, on a farm in northeast Thailand. He was three years away from being taken, trafficked to America, his mother brutally murdered, and his life consumed in the wreckage of real abuse by a real predatory monster while all the “officials” looked the other way. Our lives, his and mine, were on a collision course.

When this blog had its debut in July, 2009, a small number of self-described “faithful” Catholics, and some faithfully anti-Catholic activists, took umbrage with the notion that an accused and imprisoned priest might have such a voice in the Catholic public square. Some of them sought out anything and everything they could unearth and throw at me to discourage my writing. It was effective. Discouragement comes easily to a prisoner.

The strangest of the insults came from a man who felt obliged to tell me that he refuses to read anything written by “another Whisky Priest.” That was a bit of a mystery until months later when I read Graham Greene’s masterful 1940 novel, The Power and the Glory. Its main character is a priest without a name. He is the “Whisky Priest” known mostly for the prison of addiction.

That particular insult seemed entirely misplaced. Google did not always pay attention to punctuation back then. It turned out that the letter writer had Googled “Father Gordon MacRae” and stumbled upon a reference to an interview with actress Meredith MacRae in which she revealed, “My father Gordon MacRae was an alcoholic.” Gordon MacRae the film and Broadway star went on to win a multitude of awards for starring roles in Carousel and Oklahoma, among others. But, alas, I am not he, and nor am I the “Whisky Priest.” I have not consumed alcohol in any form other than at Mass since 1983.

But “Whisky Priest” did not quite have the force of insult the letter writer intended. Graham Greene’s “Whisky Priest” was sadly all too human, but his priesthood towered over his flawed humanity. The Power and the Glory is set in early 20th Century Mexico when an emerging totalitarian regime there outlawed the practice of Catholicism in a nation that was almost 100 percent Catholic. This is the story of the Cristeros, Catholics who rose up in civil war against a Marxist regime that tried to banish their faith. Priests were hunted; many were martyred; and those who remained, and stayed alive, were forced to abandon their priesthood, enter into marriage, and denounce the Church or face prison and eventual execution.

Many who were not martyred did as required, but not the Whisky Priest. In the most unique of literary twists, a police lieutenant made it his life’s mission to hunt down and trap the Whisky Priest. He knew of the priest’s alcoholism so he enticed him by leaving a trail of bottles of wine. The story conveys the priest’s spiritual battle within himself as he consumed the wine to silence his addiction while through grace and sheer force of will always forced himself to leave enough to offer Mass all throughout the country for Catholics who remained steadfast in their faith at a time when there was no other priest.

The Whisky Priest is the most unlikely of spiritual heroes. Priesthood was his greatest cross because it placed his life, and the lives of those who sought his sacraments, in grave danger. It was also his liberation. When he was finally arrested, the Police Lieutenant asked him why he stayed only to be captured and likely martyred:

“If I left, it would be as if God in all this space between the sea and the mountains ceased to exist. But it doesn’t matter so much my being a coward and all the rest. I can put God into a man’s mouth just the same — and I can give him God’s pardon. It wouldn’t make any difference to that if every priest in the Church was like me.”

A Voice in the Wilderness

But also among the din of objections to my writing came far louder and more voluminous words of encouragement from other sources. Among them, as most readers know, was Cardinal Avery Dulles who famously wrote,

“Someday your sufferings will come to light and will be instrumental in a reform. Someone may want to add a new chapter to the volume of Christian literature from those unjustly in prison. In the spirit of St Paul, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Fr Walter Ciszek, and Fr Alfred Delp, your writing, which is clear, eloquent and spiritually sound, will be a monument to your trials.”

I was stunned to receive the support of this nation’s most prolific Catholic writer and prelate. But I was not sure that I believed him. Then, 15 years later as yet another ordination anniversary loomed, I learned from others just a week ago about a brief article at the blog, Les Femmes — The Truth. The writer, Mary Ann Krietzer, had written a letter to me about a year earlier.

I get many letters, a few of them hate mail but most of them strong gestures of support. However I fail, though not by choice, to answer most. I can purchase only six typewriter ribbons per year so I must preserve them for BTSW posts. I had carpal tunnel surgery on both hands so writing a large volume by hand is most difficult. I came upon a letter kindly sent to me from Mary Ann Krietzer that I somehow had misplaced. Six months later, near Pentecost, I discovered it in a pile of paper and wrote a brief reply. That prompted her to write a post on her widely-read blog entitled, “Fr Gordon MacRae and Beyond These Stone Walls.”

In many ways I was shocked by it. The author gave clear voice to all that Cardinal Dulles had predicted, without even knowing that he had predicted it. Mary Ann Kreitzer’s article included this passage published earlier by a recently ordained deacon that was given a magnified voice at Les Femmes — The Truth:

“There are few authentic prophetic voices among us, guiding truth-seekers along the right path. Among them is Fr Gordon MacRae, a mighty voice in the prison tradition of John the Baptist, Maximilian Kolbe, Alfred Delp, SJ, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.”

For people who base their core purpose upon a lie, the truth is an especially threatening thing. I had no idea that my voice in the wilderness was no longer in the wilderness. I hope you will read Ms. Krietzer’s post linked again below. She provided articulate balance to the loud din of those who pursued me across the land just to disparage and demean. For my part, after reading Mary Ann Krietzer’s post, I just wanted to go hide under my bunk. But in truth, as I mark 42 years of priesthood in the deep peripheries to which Pope Francis once summoned the gaze of the whole Church, I remain a man in prison, and a priest in full.

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae: I want to thank you for your support and prayers. I also want to ask for your prayers for a young man who encountered this blog along with his mother and father and family, back in its infancy in 2009. They have been devoted readers ever since. On May 29 this year Ben Feuerborn became Father Ben Feuerborn when he was ordained a priest in Lincoln, Nebraska. His first Mass went without a hitch — perhaps because no one had left their car lights on. His second Mass was offered at a Benedictine abbey near Kansas City, Missouri. While Father Ben was in the sacristy vesting for Mass, his mother spotted a plaque under the title “Ad Altare Dei” (To the altar of God). She took out her phone and snapped this photo, which I received this week. It is a bit of a mystery, one among many.

+ + +

We also recommend these related posts:

Fr. Gordon MacRae at Beyond These Stone Walls

by Mary Ann Krietzer @Les Femmes — The Truth

On the Day of Padre Pio, My Best Friend Was Stigmatized

by Pornchai Maximilian Moontri

A Mirror Image in the Devil’s Masterpiece

by Dilia E. Rodríguez, Ph.D.

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

Evenor Pineda and the Late Mother’s Day Gift

Like many single mothers of prodigal sons, Evenor Pineda’s Mom struggled against formidable forces — the streets, the gangs, jail, then prison — but never gave up.

Like many single mothers of prodigal sons, Evenor Pineda’s Mom struggled against formidable forces — the streets, the gangs, jail, then prison — but never gave up.

May 15, 2024 Fr Gordon MacRae

Toya Graham is not exactly a household name, but odds are you’ve seen her. Just about every cable and network news outlet in America carried a video clip of Mrs. Graham chasing her masked and hooded teenage son down a Baltimore street back in 2015. She searched for him, and found him in the middle of an urban protest surrounded by police in riot gear. Not long after she left with her prodigal son in tow, the crowd erupted into a rampaging mob that laid waste to one of the poorest neighborhoods of Baltimore.

As the news footage of a desperate mother chasing down her son went viral, Toya Graham quickly became a national icon of sorts, a single mother struggling to raise her son alone against the lure of the streets. My heart went out to this woman. The very scene she unwittingly brought to national attention was one I described in a post entitled, “In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men.” Seven years after it was published, it was cited by the National Catholic Register as being among the best of Catholic blogs because it struck a very exposed nerve in our culture.

I hope you will read it and share it in these weeks between Mother’s Day and Father’s Day in America. That article has been the most widely read and shared post at Beyond These Stone Walls, having been republished in hundreds of venues and shared over 30,000 times on Facebook alone. It told a story that might be the real catalyst behind the looting, raging mobs that overtake inner city streets across America. It is a story about much more than race.

Toya Graham became an icon of the one thing necessary to keep a peaceful and legitimate protest from descending into a lawless mob: a loving, caring, responsible and available parent — preferably two of them in faithful partnership — willing to meet head-on the challenge of parenting. In the now epidemic absence of fathers in neighborhoods like that one in Baltimore — and in prisons all over America — Toya Graham met that challenge heroically, and alone.

A few days later, Mrs. Graham and her son, Michael Singleton, appeared on one of the morning network news shows. He presented as a remarkably articulate and respectful son, traits that no doubt spoke more of his Mom than himself, and he joked that running toward the police in riot gear on that street that day made more sense to him after seeing the look on his mother’s face.

For her part, Mrs. Graham apologized to the nation for a few foul words delivered before cameras in the heat of the moment, but she apologized to no one for the almost comical smack she delivered to the son who towered over her. “As long as I have breath in my body,” she said, “my son will not be down there doing that!” If this blog had a Mother-of-the-Year award, it would have gone to Toya Graham.

But she would have to share it with Rosa Levesque. Rosa is the mother of another young man I know, Evenor Pineda, and I have come to admire her very greatly even though we have never actually met. You have previously met Evenor Pineda however. He appears in a photograph that you will see again below.

Evenor's is a remarkable story of the undying love and urgent hope of a single mother struggling to redeem her prodigal son. It is best to tell it in Evenor’s own words:

Here Is Evenor Pineda:

“I was born on Wednesday, December 30, 1981 to immigrant parents in Nashua, New Hampshire. My father, Cosme, was a political refugee who fought on the losing side of a civil war in Nicaragua. My mother, Rosa, was an orphan adopted into an oppressive and abusive family that emmigrated to the United States. My sister, Lina, was born two years and a day after me, and by her second birthday our mother left our father, fleeing in an attempt to protect us from the drug dealing and growing addiction that was consuming his life and our family.

“As I grew into adolescence with the wonderful woman struggling to raise us alone, I betrayed her faith, hope, and trust by becoming the next male role model in our family to become an abuser and addict, and I added a new twist — a gang member.

“While my mother struggled to pay the bills I did everything to undermine her. Our home became a hangout for the gang. I brought alcohol and drugs into our home and police to our door, because there was no one there to stop me. Under my influence, even my younger sister began to stray into my world, but our mother took a much harder line with her, pulling her back from the brink upon which I lived.

“It wasn’t that my mother didn’t take that same hard line with me. She did. But she also knew that outside our home were the streets always luring her rebellious son from beyond her influence. She knew that she risked losing me forever, so my Mom did what she always did. She struggled as best she could.

“Between the ages of fifteen and eighteen I would drop out of school, be arrested a dozen times, incarcerated four times in both juvenile detention and then county jails, but my mother never gave up on me. Not even when I gave up on myself.

“On my eighteenth birthday, I maxed out of a county jail and was able to land a real job. I held it for five years, but the ties to my gang grew stronger and I simply became better at evading arrest. And my Mom still struggled against them.

“By the time I was twenty-two, I had two beautiful children of my own, my son, Tito and my daughter, Nati. Fatherhood was something I had to learn from scratch, having had no personal experience of it in my life. The relationship I was in with their mother collapsed, but my mother was, as always, right there to help me raise my children. She was an incredible grandmother.

“I was balancing two different lives, however, one as a young father and family man and the other as a gangster. Those two lives collided on April 17, 2005. My friend Kaleek and I had a falling out over drugs that escalated. We both fell victim to the street culture we had embraced, and that would not release us from its grip. It ultimately took Kaleek’s life, and my freedom.

“This marked the lowest point in my life. It was the point at which I learned who my true friends were — and were not — and it reinforced how much the adage is true — that blood is thicker than water. It was a selfish moment in my life where I thought of no one but myself. I knew I suffered, but I had no idea how much I made my family suffer. By this time, my sister, Lina was serving in Iraq, and at a time when I should have been a support to my family, I instead went to prison. I had been in this place for ten years, with eight more left to serve.

“My mother had become both grandmother and mother to my children, and the one mainstay of my life who never stopped struggling to save me. So when there came a time when I had to decide who I am, I looked to the one person who might know. My mother taught me by the sheer force of example the meaning of love and sacrifice, the meaning of parenthood.

“In 2010, I became a volunteer facilitator for the prison’s Alternatives to Violence Program. I trained for this alongside two men you know: Michael Ciresi and Pornchai Moontri. In 2012, Pornchai Moontri and I graduated together from Granite State High School, an accredited school in the Corrections Special School District. My friend, Alberto Ramos.

“One day, my friend, Gordon MacRae showed me an article he wrote about our graduation. It told my friend, Alberto’s story and was titled, “Why You Must Never Give Up Hope for Another Human Being.” It was then that I realized that I must never give up on myself. I know you have seen the photograph of us that I am told is now rather famous. That is Pornchai in the middle with Alberto just behind and to his right.

“I am on the left, and clearly in the very best of company. Gordon is not in the picture, but stood next to the photographer. We were all proudly showing him our diplomas.

“In the ensuing years I served with my friend Gordon on the Resident Communications Committee (RCC), a representative group of ten prisoners that met monthly with prison administration to keep open channels of communication and to try to make this a better and safer environment. After a year I was appointed co-chairman of the RCC having been nominated for that post by Gordon. I want to thank him. At least, I think I do!

“I also was a member of Hobby Craft and its woodworking department where I have learned the skill to produce furniture and other items that were then sold to the public. I used the funds I earned to help my mother and my children, and also to further my education. Through this effort, I was able to afford one or two courses per semester at New England College which had a presence in this prison.

“I formally renounced my gang membership. There was no longer any room for that past in my present. I remember something my friend, Pornchai Moontri wrote in an article I read. ‘One day I woke up with a future when up to then all I ever had was a past.’ Sometimes the truth just smacks you in the head. Today, I find reason to be proud, not only of my mother, but my sister, Staff Sergeant Lina Pineda of the New Hampshire National Guard, and of my children. I am their future, and it is an awesome responsibility from which I must not shrink.

“When we graduated from high school in 2012, Gordon MacRae was there to hear Pornchai’s great graduation speech. He wrote about this in an article I read. I gave a speech that day, too. My mother, Rosa, was there, and I wrote it for her. Gordon later asked me for a copy, and then asked me to let him reproduce it here.”

Evenor Pineda’s Commencement Speech:

“Not everyone is fortunate enough to have an opportunity to receive an education or to have parents to encourage their education. I, however, was one of those fortunate enough to have both an opportunity and someone who cared enough to show interest in my education.

“Yet I then took for granted what I now recognize was then a luxury and I squandered a wonderful opportunity to seize a controlling stake in my future. It was a future which up until high school was very promising. All I had to do was stay the course.

“It was a far cry from other children in the world not as fortunate as I was to have a parent who cared and who valued education, children whose future is bleak, at best. The most shameful part about this is that I knew how good I had it and how bad others did.

“I know of such a woman whose childhood was the polar opposite of mine. She was parentless at the age of three, placed in an orphanage with her six sisters all of whom were eventually placed with different families. At nine she found herself in a home where she was denied an education, robbed further of her childhood, forced into a life of servitude: cooking, cleaning, caring for that family’s biological children, and abused both physically and mentally. She was told that she would amount to nothing, would be nothing.

“Yet this woman did not allow circumstance to dictate her future, and as fate would have it, when the family she was living with emmigrated to the United States, the Land of Opportunity, she did just that. She seized an opportunity and a controlling stake in her future. At the age of just seventeen in a foreign land, she struck out on her own, started her own family, learned English, and with only a third grade education, earned her GED.

“Then she earned a college certificate in her field of work, earned her citizenship, earned a home, and earned the American dream. It was a dream this woman, my Mother, struggled to obtain, and I was a product of that American dream. I was born into an opportunity not afforded to my mother, yet she — unlike me — capitalized on her opportunities.

“I had to endure great loss and suffering to finally grasp and understand to what lengths my mother had to struggle and sacrifice to solidify her place in this country, and how much it must have pained her to see me throw away the opportunities bestowed upon me.

“Not everyone is fortunate enough to have an opportunity at an education, let alone a second chance. This is why this diploma has taken on a whole new meaning. It is a step toward redeeming myself to my mother and my family. It is a symbol of my commitment to follow in the steps of my mother in pursuing the American Dream.

“I’m sorry to be late this Mother’s Day, Mom, and all the Mother’s Days past. I love you, and I thank you. I am so very proud of you. Your struggle has not been in vain.”

+ + +

Editor’s Note: Evenor emerged from prison in 2017 and has never returned. He is today the Intervention Programming Coordinator for the Manchester Police Athletic League where he diverts many young people from the lure of the streets. He has also assisted other inmates emerging from prison by challenging them to employ the tools needed to move forward. He is today an outstanding father thanks to the support of an outstanding mother.

Thank you for reading and sharing Evenor’s profoundly moving story. You may also like these related posts from Beyond These Stone Walls:

In the Absence of Fathers: A Story of Elephants and Men

Why You Must Never Give Up Hope for Another Human Being

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.

The following is a translation from the Polish in the image above: “Eighth Star in the Crown of Mary Queen of Peace” “Chapel of Perpetual Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament at Niepokalanow. World Center of Prayer for Peace.” “On September 1, 2018, the World Center of Prayer for Peace in Niepokalanow was opened. It would be difficult to find a more expressive reference to the need for constant prayer for peace than the anniversary of the outbreak of World War II.”

For the Catholic theology behind this image, visit my post, “The Ark of the Covenant and the Mother of God.”

In a Mirror Dimly: Divine Mercy in Our Darker Days

Your friends behind and Beyond These Stone Walls have endured many trials. Divine Mercy has been for them like a lighthouse guiding them through their darkest days.

Your friends behind and Beyond These Stone Walls have endured many trials. Divine Mercy has been for them like a lighthouse guiding them through their darkest days.

April 3, 2024 by Fr Gordon MacRae

Editor’s Note: In 2018, Mrs. Claire Dion visited Pornchai Moontri in prison and wrote a special post about the experience which we will link to at the end of this one. In the years leading up to that visit, the grace of Divine Mercy became for them both like a shining star illuminating a journey upon a turbulent sea. Divine Mercy is now their guiding light.

+ + +

I had clear plans for the day I began writing this post, one of many at this blog about Divine Mercy. But, as often happens here, my best laid plans fall easily apart. The prison Library where I have been the Legal Clerk for the last dozen years has been open only one day per week for several months due to staff shortages. During down times in the Law Library, I am able to use a typewriter that is in better condition than my own. So this day was to be a work day, and I had lots to catch up on, including writing this post.

I kept myself awake during the night before, mapping out in my mind all that I had to accomplish when morning came and how I would approach this post. Divine Mercy is, after all, central to my life and to the lives of many who visit this blog. But such plans are often disrupted here because control over the course of my day in prison is but an illusion.

Awake in my cell at 6:00 AM, I had just finished stirring a cup of instant coffee. Before I could even take a sip, I heard my name echoing off these stone walls as it was blasted on the prison P.A. system. It is always a jarring experience, especially upon awakening. I was being summoned to report immediately to a holding tank to await transport to God knows where. I knew that I might sit for hours for whatever ordeal awaited me. My first dismayed thought was that I could not bring my coffee.

It turned out that my summons was for transportation to a local hospital for an “urgent care” eye exam with an ophthalmologist. For strict security reasons I was not to know the date, time, or destination. Months ago, I developed a massive migraine headache and double vision. The double vision was alarming because I must climb and descend hundreds of stairs here each day. Descending long flights of stairs was tricky because I could not tell which were real and which would send me plummeting down a steel and concrete chasm.

So I submitted a request for a vision exam. My double vision lasted about six weeks, then in mid-February it disappeared as suddenly as it came. I then forgot that I had requested the consult. So two months later I made my way through the morning cold in the dark to a holding area where a guard pointed to an empty cell where I would sit in silence upon a cold concrete slab to await what is called here “a med run.”

Over the course of 30 years here, I have had five such medical “field trips.” That is an average of one every six years so there has been no accumulated familiarity with the experience. The guards follow strict protocols, as they must, requiring that I be chained in leg irons with hands cuffed and bound tightly at my waist. It is not a good look for a Catholic priest, but one which has likely become more prevalent in recent decades in America. During each of my “med runs” over 30 years, my nose began to itch intensely the moment my hands were tightly bound at my waist.

The ride to one of this State’s largest hospitals, Catholic Medical Center in Manchester, was rather nice, even while chained up in the back of a prison van. The two armed guards were silent but professional. My chains clinked loudly as they led me through the crowded hospital lobby. The large room fell silent. Amid whispers and furtive glances, I was just trying hard not to look like Jack the Ripper.

I was led to a bank of elevators where I was gently but firmly turned around to face an opposite wall lest I frighten any citizens emerging from one. As I stared at the wall, I made a slight gasp that caught the attention of one of the guards. Staring back at me on that wall opposite the elevators was a large framed portrait of my Bishop who I last saw too long ago to recall. I smiled at this moment of irony. He did not smile back.

A Consecration of Souls

The best part of this day was gone by the time I returned from my field trip to my prison cell. I was hungry, thirsty, and needed to deprogram from the humiliation of being paraded in chains before Pilate and the High Priests. My first thought was that I must telephone two people who had been expecting a call from me earlier that day. One of them was Dilia, our excellent volunteer editor in New York. The other was Claire Dion, and I felt compelled to call her first. Let me tell you about Claire.

As I finally made my way up 52 stairs to my cell that day, I reached for my tablet — which can place inexpensive internet-based phone calls. I immediately felt small and selfish. My focus the entire day up to this point was my discomfort and humiliation. Then my thoughts finally turned to Claire and all that she was enduring, a matter of life and death.

I mentioned in a post some years back that I grew up in Lynn, Massachusetts, a rather rugged industrial city on the North Shore of Boston. There is a notorious poem about the City but I never knew its origin: “Lynn, Lynn, the City of Sin. You never go out the way you come in.” After writing all those years ago about growing up there, I received a letter from Claire in West Central Maine who also hails from Lynn. She stumbled upon this blog and read a lot, then felt compelled to write to me.

I dearly, DEARLY wish that I could answer every letter I receive from readers moved by something they read here. I cannot write for long by hand due to carpal tunnel surgery on both my hands many years ago. And I do not have enough typewriter time to type a lot of letters — but please don’t get me wrong. Letters are the life in the Spirit for every prisoner. Claire’s letter told me of her career as a registered nurse in obstetrics at Lynn Hospital back in the 1970s and 1980s. It turned out that she taught prenatal care to my sister and assisted in the delivery of my oldest niece, Melanie, who is herself now a mother of four.

There were so many points at which my life intersected with Claire’s that I had a sense I had always known her. In that first letter, she asked me to allow her to help us. My initial thought was to ask her to help Pornchai Moontri whose case arose in Maine. The year was late 2012. I had given up on my own future, and my quest to find and build one for Pornchai had collapsed against these walls.

Just one month prior to my receipt of that letter from Claire, Pornchai and I had professed Marian Consecration, after completing a program written by Father Michael Gaitley called 33 Days to Morning Glory. It was the point at which our lives and futures began to change.

Claire later told me that after reading about our Consecration, she felt compelled to follow, and also found it over time to be a life-changing event. She wanted to visit me, but this prison allows outsiders to visit only one prisoner so I asked her to visit Pornchai. He needed some contacts in Maine. The photo atop this post depicts that visit which resulted in her guest post, “My Visit with Pornchai Maximilian Moontri.”

The Divine Mercy Phone Calls

From that point onward, Claire became a dauntless advocate for us both and was deeply devoted to our cause for justice. In 2020, Pornchai was held for five months in ICE detention at an overcrowded, for-profit facility in Louisiana. It was the height of the global Covid pandemic, and we were completely cut off from contact with each other. But Claire could receive calls from either of us. I guess raising five daughters made her critically aware of the urgent necessity of telephones and the importance of perceiving in advance every attempt to circumvent the rules.

Claire devised an ingenious plan using two cell phones placed facing each other with their speakers in opposite positions. On a daily basis during the pandemic of 2020, I could talk with Pornchai in ICE detention in Louisiana and he could talk with me in Concord, New Hampshire. These brief daily phone calls were like a life preserver for Pornchai and became crucial for us both. Through them, I was able to convey information to Pornchai that gave him daily hope in a long, seemingly hopeless situation.

Each step of the way, Claire conveyed to me the growing depth of her devotion to Divine Mercy and the characters who propagated it, characters who became our Patron Saints and upon whom we were modeling our lives. Saints John Paul II, Maximilian Kolbe, Padre Pio, Faustina Kowalska, Therese of Lisieux, all became household names for us. They were, and are, our spiritual guides, and became Claire’s as well by sheer osmosis.

Each year at Christmas before the global Covid pandemic began, we were permitted to each invite two guests to attend a Christmas gathering in the prison gymnasium. We could invite either family or friends. It was the one time of the year in which we could meet each other’s families or friends. Pornchai Moontri and I had the same list so between us we could invite four persons besides ourselves.

The pandemic ended this wonderful event after 2019. However, for the previous two years at Christmas our guests were Claire Dion from Maine, Viktor Weyand, an emissary from Divine Mercy Thailand who, along with his late wife Alice became wonderful friends to me and Pornchai. My friend Michael Fazzino from New York, and Samantha McLaughlin from Maine were also a part of these Christmas visits. They all became like family to me and Pornchai. Having them meet each other strengthened the bond of connection between them that helped us so much. Claire was at the heart of that bond, and it was based upon a passage of the Gospel called “The Judgment of the Nations.” I wrote of it while Pornchai was in ICE Detention in 2020 in a post entitled, “A Not-So-Subtle Wake-Up Call from Christ the King.”

Father Michael Gaitley also wrote of it in a book titled You Did It to Me (Marian Press 2014). We were surprised to find a photo of Pornchai and me at the top of page 86. Both my post above and Father Gaitley’s book were based on the Gospel of Matthew (25:31-46). It includes the famous question posed in a parable by Jesus: “Lord, when did we see you in prison and visit you? And the King answered, ‘Truly I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of my brethren, you did it to me’” (Matthew 25:39-40)

That passage unveils the very heart of Divine Mercy, and as Father Gaitley wrote so eloquently, it is part of a road map to the Kingdom of Heaven. It was Claire who pointed out to me that she was not alone on that road. She told me, “Every reader who comes from beyond these stone walls to visit your blog is given that same road map.”

The God of the Living

In Winter, 2023 Claire suffered a horrific auto accident. While returning home from Mass on a dark and rainy night a truck hit her destroying her vehicle and causing massive painful tissue damage to her body, but no permanent injury. I have been walking with her daily ever since. Miraculously, no life-threatening injuries were discovered in CT or MRI scans. However, the scans also revealed what appeared to possibly be tumors on her lung and spinal cord.

At first, the scans and everyone who read them, interpreted the tumors to be tissue damage related to the accident that should heal over time. They did not. In the months to follow, Claire learned that she has Stage Four Metastatic Lung Cancer which had spread to her spinal cord. The disruptions in her life came quickly after that diagnosis. I feared that she may not be with us for much longer. This has been devastating for all of us who have known and loved Claire. I was fortunate to have had a brief prison visit with her just before all this was set in motion.

Claire told me that on the night of the accident, she had an overwhelming sense of peace and surrender as she lay in a semi-conscious state awaiting first responders to extricate her from her crushed car. Once the cancer was discovered months later, she began radiation treatments and specialized chemotherapy in the hopes of shrinking and slowing the tumors. She is clear, however, that there is no cure. Claire dearly hoped to return to her home and enjoy her remaining days in the company of her family and all that was familiar.

As I write this, Claire has just learned that this will not be possible. Jesus told us (in Matthew 25:13) to always be ready for we know not the day or the hour when the Son of Man will come. I hope and pray that Claire will be with us for a while longer, but I asked her not to call this the last chapter of her life, for there is another and it is glorious. Just a week ago, Christ conquered death for all who believe and follow Him.

In all this time, Claire has been concerned for me and Pornchai, fearing that we may be left stranded. I made her laugh in my most recent call to her. I said, “Claire, I am not comfortable with the idea of you being in Heaven before me. God knows what you will tell them about me!” I will treasure the laughter this inspired for all the rest of my days.

This courageous and faith-filled woman told me in that phone call that she looks forward to my Divine Mercy post this year because Divine Mercy is her favorite Catholic Feast Day. I did not tell her that she IS my Divine Mercy post this year. Now, I suspect, she knows.

“Now we see dimly as in a mirror, but then we shall see face to face. Now I know only in part, but then I shall understand fully even as I am fully understood.”

— St Paul, 1 Corinthians 13:12

+ + +

Note from Father Gordon MacRae:

Thank you for reading and sharing this post. Please pray for Claire Dion in this time of great trial. I hope you will find solace in sharing her faith and in these related posts:

My Visit with Pornchai Maximilian Moontri by Claire Dion

A Not-So-Subtle Wake-Up Call from Christ the King

Divine Mercy in a Time of Spiritual Warfare

The God of the Living and the Life of the Dead

The Eucharistic Adoration Chapel established by Saint Maximilian Kolbe was inaugurated at the outbreak of World War II. It was restored as a Chapel of Adoration in September, 2018, the commemoration of the date that the war began. It is now part of the World Center of Prayer for Peace. The live internet feed of the Adoration Chapel at Niepokalanow — sponsored by EWTN — was established just a few weeks before we discovered it and began to include in at Beyond These Stone Walls. Click “Watch on YouTube” in the lower left corner to see how many people around the world are present there with you. The number appears below the symbol for EWTN.

Click or tap here to proceed to the Adoration Chapel.